Abstract

As older people have accumulated more developed networks, stronger financial positions and a greater ability to leverage resources and create more credible businesses, they are better placed to start new and more successful businesses than the younger generation. This paper presents the research that has been conducted for the ENTRUST project, which aims at designing an entrepreneurship training programme for people aged 50+ who are interested in creating new businesses to foster the sustainable development of rural areas and to provide services to tourists or other businesses that support tourism in rural areas. The results of the surveys for potential 50+ entrepreneurs (72 respondents) and experts in rural development and tourism organizations (100 respondents) show that there are perceived business opportunities in rural areas for experienced 50+ professionals. There is also a high demand for training targeted at rural tourism entrepreneurs. The interviews of experienced 50+ entrepreneurs (8) who work in cooperation with the rural community show that 50+ entrepreneurs find their work meaningful and that they want to continue working “as long as their health allows”. They greatly value the opportunity to develop the rural area and to be involved in preserving its historical and cultural heritage.

1. Introduction

Population ageing and the simultaneous decline in fertility rates are among the greatest challenges facing Western European countries [1] (p. 211). These developments have an adverse influence on the proportion of working and non-working people. Although various countries with high unemployment figures encourage early retirement of older workers by claiming that they are “creating room for youngsters wanting to work”, the future is more likely to show a shortage rather than a surplus in workforces [2] (p. 16). In fact, the employment objective of the “Europe 2020 Agenda for New Skills and Jobs”, which focuses on the ageing of the European Union’s population, is to have three out of four Europeans aged 20–64 in work. As older Europeans are in good health and can contribute to economic growth through their skills and experience, it is crucial to better exploit the potential of older people in the labor market [3] (p. 8).

According to the European Commission [4] predominantly rural areas make up half of Europe and represent around 20% of the population. However, most of the rural areas are also among the least favored regions in the EU, with a GDP per head significantly below the European average. Rural areas are facing challenges in terms of sustainable development. They can be a place of both agricultural production and other sectors, such as trade in agri-food, recreation, tourism and forestry. The countryside is an attractive place to live and work and a reservoir of natural resources and unique landscapes [5].

Despite all the challenges, rural areas also provide opportunities for entrepreneurs. According to Šimkova [6] (p. 263): “The EU member states in general want to increase the quality of life, clear or mitigate regional disparity and keep sustainable development in rural areas. Rural areas are places for living, recreational areas, cultural and natural space. The differentiation of rural areas and cities is seen in broadening of income and employment opportunities. The term “rural tourism” has been defined in a number of ways, it varies from country to country, and it is rather difficult to find a universal definition, due to its complex multi-faceted nature. Rural tourism or agro-tourism becomes very popular especially in the economically developed countries. It is its economically and socially positive impact, which allows farmers to gain additional financial sources and create new job positions for other local people. In fact, it is a very positive and ecological form of tourism. Unlike the uncontrolled, mass and purely commercial tourism, these leisure activities have a very low negative impact on the environment”.

Moreover, Cunha, Kastenholz and Carneiro [7] state that the tourism system integrates several activities, resources and stakeholders, enabling the creation of appealing overall rural tourism experiences, attracting visitors and boosting the place’s local economy if well managed and articulated. Rural territories dispose of a unique set of natural and cultural resources that might represent also good business opportunities. Local businesses and inspired entrepreneurs are crucial to transforming those resources into attractive and competitive and sustainable tourism products.

According to Komppula [8] (p. 366) small rural entrepreneurs must have a sound business model if they want to succeed in the tourism sector. Innovative new niche products are key to differentiating themselves from competitors in rural areas; thus, an entrepreneur must also have an innovative mind to generate new ideas for their businesses. Rural tourism also faces problems of quality, accessibility and price, especially in the organized activity sector, which suffers from very short seasons. Short seasons create variable demand, making it impossible for entrepreneurs to sustain a full-time business [8] (p. 366).

1.1. ENTRUST Project

The ENTRUST project is an Erasmus+ funded international training and development programme to design an entrepreneurship training programme for people aged 50+ in vocational education and training. The aim of the business envisaged in the entrepreneurship training is to meet the challenges of rural areas, to support the preservation of European culture, nature and heritage sites and to provide services to other businesses, entrepreneurial networks or tourists that support sustainable tourism in rural areas.

The ENTRUST project will create interactive tools and a learning platform with up-to-date training and support material for planning a new business. The ENTRUST project involves Finland (Haaga-Helia UAS), the Netherlands (Stichting Business Development Friesland), Ireland (Innovation and Management Centre) and Portugal (Aidlearn, Consultoria em Recursos Humanos and Domínio Vivo—Formação e Consultoria).

1.2. Research Questions and Research Design

The aim of this paper is to present the results of the surveys aimed at potential 50+ entrepreneurs, who may take part in the entrepreneurship training, and experts in rural development and rural tourism organizations. This paper also introduces the results of our semi-structured interviews of 50+ entrepreneurs, who are already entrepreneurs in rural areas and intend to continue in the future.

There are two research questions: (1) The first research question (RQ1): What kind of entrepreneurial training do potential 50+ entrepreneurs need if they want to create new businesses which promote sustainable development and tourism in rural areas? (2) The second research question (RQ2): How do 50+ rural area entrepreneurs promote sustainable development in their local communities?

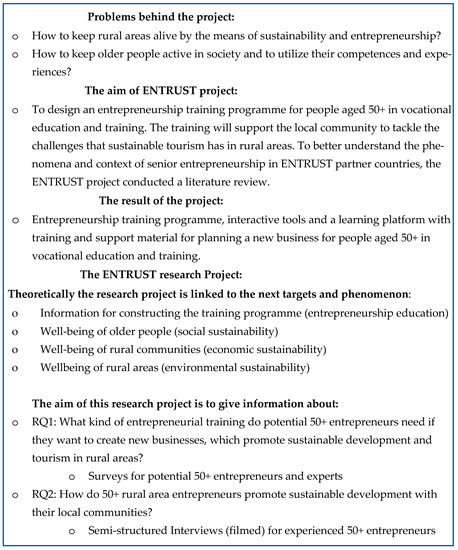

The key phenomena or concepts in this study project—namely, ageing and senior entrepreneurship, becoming an entrepreneur in older age, entrepreneurial learning and learning approaches (especially for the 50+ age group), rural entrepreneurship, sustainable tourism and sustainable development—are described in the literature review. The theoretical background is also presented in the literature review and the key phenomena of the surveys and interviews are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research design: the relationship between the ENTRUST project, the research project, key targets and phenomena.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

To better understand the phenomenon and context of senior entrepreneurship in ENTRUST partner countries, the ENTRUST project conducted a literature review. The aim was also to explore how senior entrepreneurs can promote social sustainability in their local rural areas. The purpose of the literature review in this article is to provide an overview of the project topic and related phenomena. A literature review is a method that analyzes published studies, presents the sources used and provides an overview of phenomena and research findings that are current in a specific field. There are several phases in the implementation of a literature review: defining the key words and searching for relevant research, publications, statistics, case studies, etc., as well as the definition of research questions and analysis of the research materials [9].

To consider the evolution and the historical perspective of the phenomenon [9] (p. 7), and highlighting the important role of 50+ entrepreneurship in an ageing Europe, a broad narrative description was also developed for the ENTRUST project. For the literature review, each project partner searched and reviewed literature from both a European and a national perspective. This article presents and interprets the results of an extensive literature review in a nutshell. For each of the phenomena considered, the following questions were asked: What is the meaning of the phenomenon? Why is it important? What are the challenges? What is the country-specific characteristics of the phenomenon?

2.1. Ageing and Senior Entrepreneurship

The ageing process and the classification of older individuals cannot be justified on biological and/or physiological grounds. Age is a social construct, where the allocation of people to an ageing group is made in relation to current theoretical understanding, practical interests and empirical considerations. Especially in policy-focused research, current perceptions and beliefs about older people, the legal retirement age and current life expectancy are important [10] (p. 31). In addition to the psychological process of ageing, age has many contexts, such as cultural, generational, gender, career and human resource management contexts [11] (p. 7). According to Thijssen and Rocco [2] (p. 15), the perspective of older workers is changing with respect to active ageing, bridging employment, shadow careers, second careers and becoming entrepreneurs.

Luger and Mulder [12] (p. 60) refer to several researchers when defining the term age. Human biological age refers to the functioning of the body, where ageing is related to the breakdown of body parts, while from a psychological point of view, age refers to intelligence and memory. Sociocultural age depends on society’s expectations of older people. Chronological age is the most straightforward, but often the least informative, indicator of age because the focus of the perspective is on the number, not on the individual’s background. Not all classifications provide information about individuals’ learning abilities or experiences, but different classifications are necessary for empirical research to define a specific age range and to compare different groups.

2.1.1. Senior Entrepreneurship

As life expectancy rises, senior entrepreneurs are playing an increasingly important role in economic activity. However, despite the growing importance of seniors for economic performance, policy frameworks and business, their impact is under-researched [13]. Older entrepreneurs are referred to as senior entrepreneurs, grey entrepreneurs, senior or third-age entrepreneurs, older entrepreneurs and second-career entrepreneurs, among other titles [14]. As the terms senior and grey may sound offensive; hence, Hearn and Parkin [15] recommend using the age categories: young adults (18–29 years old), middle-aged adults (30–49 years old), older adults (50–64 years old) and older adults (65–80 years old). In the ENTRUST project, the term 50+ entrepreneur is used because the planned entrepreneurship training is aimed at all people over 50.

Isele and Rogoff [13] point out that although the media portray entrepreneurs in their twenties as technological wizards and innovators, recent studies show that both the 18–29 age group and the 60+ age group have the same number of new start-ups, and in fact, the 55–64 age group has the highest start-up activity. Schøtt et al. [16] also confirm that entrepreneurship among older people is a very important economic asset both globally and regionally.

In 2018, there were 14.5 million entrepreneurs over 50 years old in the EU, representing 48% of all entrepreneurs in the region. More than 31% of these entrepreneurs employ people other than themselves [17]. In Finland, for example, the number of entrepreneurs has increased only in the 55–74 age group [18]. In 2017, 13% of all Finnish entrepreneurs aged 65–74 had previously been employees but continued to work part-time after retirement [19]. In Finland, almost half of entrepreneurs who founded a start-up in their senior years have previous entrepreneurial experience [20].

People aged 50–64 are generally better able to start and run businesses than younger people [21,22,23,24,25], and their businesses are also more successful [26]. Their success is based on social capital and the more developed networks which they have accumulated during their careers. They also have stronger financial positions, a greater ability to leverage resources and create more credible businesses over their careers [16]. Even though older entrepreneurs are more successful, according to Battisto et.al [27] (p. 15) and Love [28], 50+ owned firms experienced significant financial hardship during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pensioners are the largest group of self-employed workers in the EU. In 2018, 48% (14.5 million) of all self-employed people were aged over 50. More than 31% of these self-employed also employ others, so to prevent the loss of these businesses and jobs, policymakers should support business transfers [17] and not only start new businesses.

2.1.2. Reasons for Becoming an Entrepreneur at an Older Age

Older entrepreneurs can be divided into three groups: (1) those who worked as employees and become entrepreneurs as they retired; (2) those who worked as employees and retired but later become an entrepreneur; and (3) former entrepreneurs who continue their entrepreneurship after retirement [29]. Early retired entrepreneurs can be sub-divided into three types: for some, becoming self-employed is a rational choice; some have had a desire to be entrepreneurs but, for various reasons, have not been able to realize this desire earlier in their career; and some would prefer to return to their former roles as employees, even though they might do well as entrepreneurs (e.g., [23,30]). The earlier experience of entrepreneurship or family entrepreneurship might also be a reason to continue or become an entrepreneur at an older age as they are too busy running their business to spend time thinking about the distant future and retirement, and others cannot imagine a time when they are not running the business. According to Calabrò and Valentino [31], more than half (53%) of all family CEOs plan to retire between the ages of 61 and 70, with 27% planning to retire after age 70.

Escuder-Mollon et al. [32] found that lifelong learning in later life is becoming more common, but instead of meeting work-related needs and qualification requirements, older people have more personal needs: curiosity, a desire to understand the environment, integration, pleasure or staying active. Personal goals improve quality of life; education increases well-being and understanding of oneself and society. Finding and achieving personal goals helps older learners to feel that they are contributing to and being part of society [32]. Compared to other age groups, older people show the highest relative prevalence of the necessity motivation for entrepreneurship due to a lack of other options for a sustainable livelihood [16]. Older jobseekers are found to be driven solely by a “get out of unemployment” entrepreneurial dynamic and thus by necessity entrepreneurship [33].

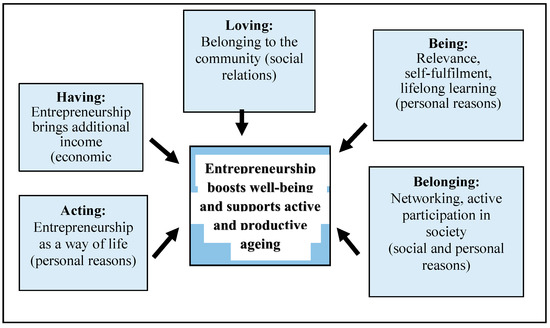

Römer-Paakkanen and Takanen-Körperich [34] studied older age women entrepreneurs and found that commitment to work and meaningful activities motivate entrepreneurs at an older age. Aging people may also have a combination of social, personal and financial reasons suitable for becoming an entrepreneur. These reasons can be grouped into five categories, as shown in Figure 2: entrepreneurship as a means of economic support (having); belonging to a community (loving); meaningfulness, self-fulfillment and lifelong learning (being); networking and active participation (belonging); and entrepreneurship as a lifestyle (acting).

Figure 2.

Factors that influence aging people to continue or start their self-employment [34], (Römer-Paakkanen and Takanen-Körperich modified from Allard [35] and Raivio and Karjalainen [36] (pp. 15–17).

According to Diener, Lucas and Oishi [37], subjective well-being (SWB) reflects an overall evaluation of the quality of a person’s life from her or his own perspective. Different people likely weigh different objective circumstances differently depending on their goals, their values and even their culture. Presumably, subjective evaluations of quality of life reflect these idiosyncratic reactions to objective life circumstances in ways that alternative approaches (such as the objective-list approach) cannot.

Aslam and Corrado [38] distinguish between a pair of concepts: personal functioning, which describes how much control individuals have over their lives and the extent to which they perceive their activities as having purpose; and inter-personal functioning, referring to what the individual does for other people or for their community in terms of pro-social behavior.

The OECD [39] (p. 5) conceptual framework to measure regional well-being built on over ten years of work focusing on measures of people’s well-being and societal progress to create the Better Life Initiative, which proposes to measure well-being through a multi-dimensional approach. The OECD conceptual framework for measuring well-being in regions and cities, for example, focuses both on individuals and on place-based characteristics, as the interaction between the two shapes people’s overall well-being. Wiklund, Nikolaev, Shir, Foo and Bradley [40] define entrepreneurial well-being as “the experience of satisfaction, positive affect, infrequent negative affect, and psychological functioning in relation to developing, starting, growing, and running an entrepreneurial venture”. Nikolova [41], in her study, found that self-employment improves mental health, and in the case of opportunity entrepreneurs, also physical health.

Kautonen, Halvorsen, Minniti, and Kibler [42], in their study, found robust evidence that the dominant assumption of a positive and significant relationship between switching to entrepreneurship and improvement in perceived self-realization opportunities holds in the context of late-career entrepreneurship. They also found that individuals who switch to entrepreneurship desire to work longer than those who stay in paid employment, and this relationship is mediated by changes in self-realization. On the other hand, they found that a transition to entrepreneurship positively impacts self-realization only in the short term (two-year model), whereas in the medium term (four-year model), the level of self-realization returns to its pre-transition level.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Learning and 50+ Learning Approaches

Entrepreneurship is one of the key lifelong learning skills that individuals need for personal fulfilment and development, active citizenship, social inclusion and employment [43]. Education and lifelong learning also play a key role in improving the quality of life and well-being of middle-aged and older adults by strengthening social networks and social support, contributing to social solidarity and, at the same time, contributing to economic development. Older adult learning also has the potential to improve levels of productive ageing by ensuring that older workers have the necessary skills required by potential employment opportunities [44]. Entrepreneurial learning is a social process in which learning is not only part of the individual knowledge creation process but also a functional interaction with others [45]. Therefore, entrepreneurs’ social networks, such as family, friends, business partners, individuals and other professionals, such as accountants, bankers and lawyers, are important sources of learning and knowledge.

Entrepreneurial learning is contextual, i.e., entrepreneurs learn in real-life situations. This experiential learning process involves learning by doing, reflecting, experimenting and collaborating. Entrepreneurial learning is a dynamic process in which entrepreneurs act and make decisions about policies that they are not always prepared for. Entrepreneurs must take risks in an uncertain environment, and sometimes they fail. Entrepreneurs consider making mistakes and failing as important parts of learning, which triggers reflective behavior [46,47,48]. Through reflection, entrepreneurs build knowledge about their businesses and also about themselves, leading to personal development.

The learning needs of the target group should be considered when designing the training programme. However, many programmes do not consider the social, cultural or educational background of learners [49]. The different contexts of students create different learning needs. Older people’s cultural values and ways of thinking, as well as their educational and learning histories, may vary from country to country. Older people have accumulated a lifetime of experience that they bring to learning situations. Their readiness for entrepreneurship varies according to their previous life experience; some may have had work experience as employees, while some have experience as entrepreneurs. According to De Faoite et al. [49], entrepreneurship education and training initiatives need to be continuously monitored and evaluated to ensure that their objectives are being met. Kern [50] (p. 210) reminds adult education providers to define the target group precisely, to reflect on their interests and to consider that learning arrangements are not only obliged to the requests of participants but are also intended to assist them in developing new learning interests and to address their conscious learning needs.

A learning environment for entrepreneurial learning should support learner-centered learning rather than teacher-centered learning. The role of the teacher is to facilitate and guide learners during the learning process. However, the responsibility for organizing knowledge lies with the learners themselves. Learning activities should be context, problem and/or opportunity based. Contextual learning differs from classroom learning, where knowledge is presented in the abstract and out of context [51].

Learning methods should include both individual, experiential learning and collaborative learning, but the pace of learning can vary between learners, and this should be considered when designing the learning environment [51,52]. In group work, older learners can share their experiences and develop social skills, self-esteem, confidence and motivation. Other learning methods that enhance entrepreneurship and new business creation are, e.g., lectures, discussions, role-plays, case studies, feedback discussions, videos and simulations.

If a person wants to remain active in old age, he/she needs to acquire more skills to remain competitive in the labor market. Hessel [52] argues that when the educated age group reaches the age of 50–55, they have a better chance of finding employment in later life. The specific characteristics of older workers, such as their education and learning history, should be recognized, as workers who are not used to continuous learning may be reluctant to participate in training. Competitive learning situations should therefore be avoided. Training should consider differences between individuals—for example, in the time required for learning—and self-learning should be encouraged. However, Formosa [53] stresses the principle of inclusion, according to which older people should not be treated as a separate group but should be integrated into the community while ensuring that their specific needs and interests are met. Socci, Clarke and Principi [54] state that active aging could be considered as an umbrella concept, including many paid and unpaid activities, among which are voluntary and community work. Thus, active aging emphasizes a holistic and life-course approach, including quality of life, physical and mental well-being and social participation, leading to a “win–win” situation, where individuals (micro level), organizations (meso level) and society (macro level) benefit from the adoption and implementation of active aging policies, strategies, and initiatives.

Desjardin and Rubenson [55] state that adult education scholars distinguish between three broad types of barriers to participation: dispositional, or the individual’s attitudes and preferences; situational, referring to the circumstances of the individual’s life; and institutional, denoting the practices and requirements of providers. While these are descriptive rather than theoretical categories, they concisely summarize what is undoubtedly a wide range of factors that can inhibit adult participation in learning in general, and participation by older workers more specifically [55].

2.3. Sustainable Development and Sustainable Tourism

Sustainable development means meeting the needs of the present whilst ensuring that future generations can meet their own needs. It has three main pillars, i.e., components: economic; environmental; and social. To achieve sustainable development, policies in these three areas must work together and support each other [56]. Sustainability can be visually represented in three different ways: by three pillars, by three intersecting circles centered on overall sustainability or by three “concentric” circles [57].

There are also other interpretations of sustainability, as sustainability can be defined in relation to only one pillar (economic, environmental or social), therefore involving the sustainability of some natural processes or sustainability related to social phenomena. This interpretation focuses on an impact analysis and does not necessarily identify a long run analysis [58] (p. 64).

According to Roger et al. [59], social sustainability means meeting the needs of human well-being. To implement the various innovations that will transform societies in the direction of environmental sustainability, it is necessary to have well-functioning societies—from a social, political and economic standpoint—that can meet the new challenges successfully. To provide the resources necessary for sustainable development of the communities most in need, we must ensure a more equitable global distribution of resources and empowerment. In the developed world, this will also require that business plans and government policies be directed at steady-state rather than perpetual growth economic models.

“The Global Sustainable Tourism Council” (GSTC) [60] has defined criteria that serve as global standards for tourism and tourism sustainability. The criteria are used for education and awareness-raising, for decision-making, measurement and evaluation by businesses, government agencies and other types of organizations, and as a basis for certification. “The GSTC criteria build on decades of previous work and experience around the world and take into account the numerous guidelines and standards for sustainable tourism from every continent. They reflect our aim to achieve a global consensus on sustainable tourism. The process of developing the criteria was designed to follow the ISEAL Alliance, an international body that provides guidelines for the development and management of sustainability standards in all sectors. This code is based on the relevant ISO standards. The criteria are the minimum, not the maximum, that companies, governments and sites must achieve to approach social, environmental, cultural and economic sustainability. As each destination has its own culture, environment, customs and laws, the criteria are designed to be adaptable to local conditions and are supplemented by additional criteria for specific locations and activities” [60].

2.4. Rural Tourism

The OECD [61] (p.3) defines a rural area as follows: “At the local level, a population density of 150 persons per square kilometers is the recommended criterion. At the regional level, geographical units are grouped according to the proportion of rural population into three types: predominantly rural (50%), significantly rural (15–50%) and predominantly urbanized (15%)” [61] (p. 3).

According to Lanfranchi and Giannetto [62] (p. 218), in a rural area, the main problems derive principally from depopulation, i.e., the exodus of a large number of people from the “campaigns” for the cities. Often, this migration is composed of qualified young people who cannot find any source of income in the area. Effects have frequently triggered a double array: the low ratio of economic activity and agricultural work, which consequently generates low farm incomes (in this case is called push effect); or the growth of labor demand in other sectors, which consequently generates more income (pull effect). The problem of depopulation is due to the distorting effects chain, such as the one linked to the suppression of isolation facilities (public and private services in small communities tend to shrink and, in some cases, to disappear).

According to the UNWTO [63], tourism can be an effective means of providing socioeconomic opportunities for rural communities as it can help with increasing the attractiveness and vitality of rural areas, mitigating demographic challenges, reducing migration and promoting a range of local resources and traditions while upholding the essence of rural life.

The term rural tourism has been defined in a number of ways; it is rather difficult to find a generally valid definition, due to its multi-faceted and complex nature. According to Ana [64], all things considered, rural tourism, agro-tourism and ecotourism have common points regarding the type of tourists who choose this kind of holidays and the quality of time they aspire to, but also in terms of trends, conditions and principles the bodies and communities involved tend to be guided by. Arslan and Ekren [65] (p. 2579) refer to Soykan’s [66] definition of rural tourism as a form of tourism integrated with the natural environment, rural settlements and local economic activities.

Rural tourism can also be defined as the movement of people from their usual place of residence to a rural area for a minimum of 24 h and a maximum of six months for the sole purpose of leisure and pleasure [67]. Rural tourism refers to all tourism activities in a rural area. Fleischer and Pizam [68] use the term “rural holiday”, where the tourist spends most of his/her holiday time recreationally in a rural environment on a farm, in a farmhouse or in the surrounding area. As tourism is often seen as an important means of development in marginal rural areas, such development is believed to appeal to a postmodern market seeking “unique” experiences [69].

Cultural authenticity and natural resources are important tools for countries and destinations to use in their efforts to attract tourists. When tourism is based on broad stakeholder participation and sustainable development principles, it can raise awareness of cultural and environmental values and help finance the protection and management of protected and sensitive areas [70]. Cultural heritage, in its broadest sense, is both a product and a process, which provides societies with a wealth of resources that are inherited from the past, created in the present and bestowed for the benefit of future generations. Most importantly, it includes not only tangible but also natural and intangible heritage [71]. World Heritage properties are important travel destinations, which have a great potential impact on local economic development and long-term sustainability [72].

3. Research Methods and Data

The approach in this research is abductive and guided by iteration between data and theory [73]. The aim of the research project is to acquire insight into interpreting and understanding the meanings of core phenomena of this study [74] (p. 33) and to deepen understanding of 50+ entrepreneurship in rural areas in four European contexts. The research is driven by an interest in producing practical knowledge for creating training for 50+ potential entrepreneurs. As information is gathered from three different target groups, the research requires both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. This multiple case research strategy is chosen to explore the real-life situations of 50+ entrepreneurs in rural areas [75,76].

The data for research question 1 were collected through a survey in four ENTRUST partner countries (the Netherlands, Ireland, Portugal and Finland). The questionnaires were targeted at two different audiences: experts in the tourism industry and regional development; and potential 50+ entrepreneurs. The survey questions were structured in line with the previous literature and from which the following themes were identified: (a) experts’ perceptions of entrepreneurial potential and challenges of entrepreneurship in tourism-related businesses in rural areas; (b) entrepreneurial aspirations of potential 50+ entrepreneurs in rural areas; and (c) key topics and methods suitable for 50+ entrepreneurship training. The questionnaire consisted of multiple-choice questions, open questions and statements, which respondents rated on a Likert scale of 1 to 4 (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree).

In the absence of registered data on target groups, respondents for both surveys were selected by snowball sampling in all countries. Both surveys were carried out by e-mail between April and July 2022. A total of 100 expert respondents and a total of 72 potential 50+ entrepreneur respondents were reached.

In the survey analyses, Likert scale analysis was used to calculate the mean scores for the statements. The results show the range of means for the four countries. The results of the multiple-choice questions are presented as percentages, i.e., the percentage of respondents who selected a statement.

To understand the contextual dimensions, we use an explorative and interpretive approach [77] in semi-structured interviews of 50+ entrepreneurs. The data for research question 2 was collected between April and September 2022 through eight face-to-face interviews, which were also filmed. Two interviews were conducted with entrepreneurs or entrepreneurial couples from each partner country (the Netherlands, Ireland, Finland and Portugal). The semi-structured interviews focused on how senior entrepreneurs in rural areas contribute to economic, social and environmental sustainability. The filmed semi-structured interviews were analyzed by building interpretations around each filmed interview, and the evidence was re-examined using thematic analysis [78] (p. 36). The interviews were then analyzed from different perspectives in an iterative process under three key elements: the contribution of 50+ entrepreneurs to rural economic, social and environmental sustainability. The filmed documentaries complement the interviews and present the business environment and landscape. The documentaries will also be used as best practice examples and training materials in the upcoming entrepreneurship training.

To save the time and costs of both the interviewee and the interviewer, nowadays, more and more video-based research and video interviews online are conducted. De Villiers, Farooq and Molinari [79] use the term “video interviews” to refer to qualitative research interviews (i.e., semi-structured and unstructured in-depth interviews) conducted by using online video communication technologies, including hardware (such as computers and smart phones) and software (such as Skype, Zoom and WhatsApp), which allow the interviewer and interviewee to see (video) and talk (audio) to each other in real-time, i.e., live. As the aim in the ENTRUST project was also to use those short documentary films as teaching materials in the potential entrepreneurs’ training, the online video interview material is not suitable for describing best-practice cases and their businesses. The best-practice documentary films (length about 15 min each and trailers) will be published both on ENTRUST project website and on the interviewed entrepreneurs’ websites.

4. Results

4.1. What Kind of Entrepreneurial Training Do Potential 50+ Entrepreneurs Need If They Want to Create New Businesses Which Promote Sustainable Development and Tourism in Rural Areas (RQ1)?

The number of respondents to both surveys (Table 1) was small: 72 potential 50+ entrepreneurs and a total of 100 expert responses. As the aim was to find ideas for designing entrepreneurship training in rural areas and not to describe or compare populations, the small number of respondents does not compromise the usefulness of the results or the reliability of the study. In addition, the target group of the survey was 50+ potential entrepreneurs who would be interested in starting a business in a rural area, regardless of where they lived at the time of the survey. The survey of experts focused in particular on people specialized in rural entrepreneurship and tourism business.

Table 1.

Number of respondents in the four target countries.

4.1.1. Experts’ Views on the Entrepreneurial Potential and Challenges of Entrepreneurship for Tourism-Related Business

Experts (n = 100) felt that rural areas have a lot of opportunities for entrepreneurs (average 3.4–3.8) and that it is important to make local cultural heritage visible (average 3.6–3.8), which is why they felt that providing entrepreneurship training is important for the development of tourism in the rural areas (average 2.8–3.7).

According to experts from all four countries, the tourism sector faces many challenges in rural areas. During COVID-19, many workers were forced to leave their jobs and change sectors, which, as the situation has improved, has led to staff shortages in many businesses. For many entrepreneurs, the pandemic was a financial burden, and many were forced to close their businesses. More recently, high inflation has contributed to increased costs and made it more difficult for many entrepreneurs to do business.

Infrastructure was seen as a challenge in all countries. For example, in rural areas, there is not enough public transport, which means that tourists are forced to rent a car. Inadequate broadband and digital services were perceived as a problem in countries such as Ireland, while in Finland they were good. Many natural and cultural sites were perceived as having few services or being otherwise poorly managed; for example, some sites have poorly marked trails.

In rural areas, tourism is often seasonal and there has been no success in creating new attractive activities outside the season. In addition, slow spatial planning hampers tourism development in some areas. Since rural businesses are small, entrepreneurs often must do all the work themselves.

Table 2 summarizes the main challenges faced by entrepreneurs according to the experts (n = 100). While there were differences in the responses of experts from different countries, access to labor (71%), infrastructure (56%) and access to finance (54%) emerged as the main challenges for entrepreneurship in rural areas in all partner countries.

Table 2.

Experts’ views on the main challenges for entrepreneurs in rural areas (n = 100).

Other challenges for entrepreneurs in rural areas include business, productization, networking, marketing and digital skills. Regional actors should cooperate more to develop services. Many entrepreneurs are also reluctant to change and do not understand the importance of quality of service, for example. A Finnish expert described the mindset of entrepreneurs: “... level 2–3 is enough for me, when the customer wants level 4–5”. The demands of sustainable tourism has also led to a reluctance to invest among entrepreneurs.

4.1.2. Entrepreneurial Aspirations of Potential 50+ Entrepreneurs in Rural Areas

Of potential 50+ entrepreneurs, 25% plan to become entrepreneurs in future. Of those entrepreneurs, 50% who already have a previous business in rural areas intend to continue their business after retirement (Table 3).

Table 3.

Entrepreneurial aspirations of potential 50+ entrepreneurs in rural areas (n = 71).

Potential 50+ entrepreneurs felt that their long careers in a wide range of jobs and extensive life experience put them in a good position to succeed as entrepreneurs in the future. One respondent describes this as follows. “I am an older entrepreneur. I have a lot of life experience that will help me in the future”. Entrepreneurs also mentioned that sales skills, extensive networks, the ability to work hard, learning from mistakes, problem-solving skills and an eagerness to learn new things contribute to success as an entrepreneur. Overall, respondents felt that they had a good chance of success (average 2.7–3.1) if they started a business.

Respondents rated their ability to reflect, get along with different people, assess the consequences of ideas and actions and project management skills very highly (average 3.3–3.6). In addition, some respondents mentioned that they had important skills in creative thinking, interpersonal skills, networking skills, openness and a willingness to help people find solutions to their problems. On the other hand, respondents considered their ability to tolerate uncertainty, take risks and design and develop new products and services to be only slightly above average (average 2.5–3.2).

Table 4 shows the reasons given by potential 50+ entrepreneurs (n = 72) for becoming or remaining self-employed. The most important reasons for becoming or remaining an entrepreneur were the desire to develop and use their skills (65%) and the desire to participate actively in society (46%), while belonging to the community (22%) or the need to earn extra money (27%) were somewhat important reasons for becoming or remaining an entrepreneur.

Table 4.

Reasons given by potential 50+ entrepreneurs for becoming or remaining self-employed (n = 72).

Respondents to the ENTRUST survey cited lack of finance, bureaucracy, lack of confidence in their ideas, lack of courage, old age, working alone, lack of time and better income from paid work as factors preventing them from becoming entrepreneurs.

The main survey findings of the ENTRUST project were very similar to those of the Erasmus+ MyBusiness project [80], which conducted a focus group interview to find out what barriers or needs Irish unemployed older people might experience when considering becoming an entrepreneur. In both studies, the main barriers to starting a business were a lack of self-confidence and identification of personal skills, such as insufficient IT skills, and the perceived riskiness of taking out a bank loan at an older age. Both focus group participants and survey respondents felt that they should have mentors, good networks and information about organisations supporting entrepreneurship if they wanted to become entrepreneurs.

4.1.3. Key Topics in 50+ Entrepreneurship Training

When asked about pedagogical solutions for entrepreneurship training (Table 5), half of the respondents (50%) felt that personalized guidance supported their professional learning. Peer learning with other entrepreneurs was also perceived as useful (48%). Combining contact and online learning was seen as a good solution by 40% of respondents, while classroom learning was favored by only 4%.

Table 5.

What type of entrepreneurship training do you feel supports you to become an entrepreneur? (n = 73).

When asked about the topics of entrepreneurship training (Table 6), both experts and potential 50+ entrepreneurs felt that creating new ideas, anticipating the future and identifying opportunities, developing sustainable tourism experiences and service design were important. Both groups of respondents considered both knowledge of national and European funding sources and leadership skills as unnecessary elements of training.

Table 6.

Experts’ and potential 50+ entrepreneurs’ views on the inclusion of different topics in the training.

4.2. How Do 50+ Rural Area Entrepreneurs Promote the Sustainable Development in Rural Areas (RQ2)?

Data for research question 2 were collected through eight semi-structured interviews (in the form of films). The interviews focused on the 50+ entrepreneurs with experience of entrepreneurship in rural areas, as their experience is valuable in designing training for potential entrepreneurs. The descriptions of each case are presented in Table 7. In five cases, there were entrepreneurial couples; and two cases were male entrepreneurs. One case was a non-profit organization, originally a farmhouse, which has been transformed into a landscape observatory. It is a center for landscape demonstration, research and promotion.

Table 7.

Description of cases.

This paper presents the contribution of 50+ entrepreneurs to sustainable development in rural areas using the following categories of sustainability: social–environmental, social–economic and economic–environmental. The results of research question 2 are presented in the following sections.

4.2.1. Entrepreneurs’ Influence on Social–Environmental Sustainability in the Region

In areas where entrepreneurs had invested in old historic buildings, such as manors, the importance and maintenance of historic and cultural heritage buildings was considered important. In a few cases, passing on family property and inheritance from one generation to the next was important to ensure intergenerational continuity. “We are already in the sixth generation, so we want to preserve it and, I hope my children and grandchildren continue to do so”. (Case 7). The family heritage is also reflected in intergenerational learning, where the older generation passes on the knowledge and skills of the profession to the next generation.

Entrepreneurs stressed the importance of being given the opportunity to use historical and cultural heritage in their business. Many entrepreneurs were committed to community development. They organized events and activities for residents and visitors that contributed to people’s well-being. These activities brought joy, pride, and well-being to the entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs clearly took pride in their community or village.

4.2.2. Entrepreneurs’ Influence on Social–Economic Sustainability in the Region

The economic aspect is an important factor in rural businesses, as in any other business. A few entrepreneurs said that their businesses had grown; this usually meant adding new products and services to their product range. Improved economic conditions in the region also brought more employment opportunities to the area, so local entrepreneurs recruited full and part-time workers. The use of historic buildings for businesses is an important economic factor in rural areas. Entrepreneurs maintain and renovate historic buildings, which increases their value and life cycle.

Entrepreneurs underlined the importance of cooperation and networking in doing business in rural areas. The entrepreneurs bought products and services from other entrepreneurs in the area.

“We have a very good cooperation with local entrepreneurs. We have our own beer that has been made in the local brewery. In addition, we also try to take everything that we need from local producers”.(Case 1)

When entrepreneurs trade with each other, they share knowledge and experience, contributing to a common pool of local knowledge. They also promote the products and services of other entrepreneurs in the region to their own customers. In this way, entrepreneurs support each other financially.

4.2.3. Entrepreneurs’ Influence on Economic–Environmental Sustainability in the Region

Many of the entrepreneurs interviewed arranged ecotourism activities to create nature-based experiences and generate income. Entrepreneurs understood the value of nature and promoted conservation and sustainable tourism practices. Customers were taught to protect nature during their stay in the area.

“I think it’s pretty cool to be a part of history. The same applies when we have customers, then we require them to environmentally friendly way of working. For example, on the lake we are not allowed to drive motorboat at all. We have rowing boats. The intention is to keep this place as it is now”.(Case 2)

Entrepreneurs strive to live in harmony with nature. For example, entrepreneurs sourced food from local producers; some picked their own berries for jam or kept beehives for honey production. Entrepreneurs who had their own food production are one example of the coexistence between the entrepreneur and nature.

“We have here, for example bees, which pollinate. The primary function of the bees is pollination. Of course, we get honey, and that’s nice. This is about maintaining the balance of nature, that we have bees. All our activities are based on it, that we do not change nature, but we want to preserve nature as it is today.”(Case 2)

Entrepreneurs were concerned to ensure that polluting activities, such as energy use and basic building renovation, are carried out in a way that respects nature. Examples of this are the increased use of solar panels for energy production and the renovation of buildings using natural materials.

“But, when we had to rebuild, the front end in 2020, we found out that there was hardly any isolation. So, we asked the building company to really isolate it in a very sustainable way. And they used a lot of natural materials, and actually this farm became much more sustainable. And on top of that in 2022, early this year we found out that we had more space and room for solar panels. So we installed extra solar panels to heat up the apartments. But also to use it in the water supply. And I think now, we are approaching zero kind of use of gas and fossil fuels”.(Case 5)

The entrepreneurs we interviewed operate within the framework of sustainable development. They value nature and understand that a clean natural environment is a key prerequisite for sustainable social development and economic sustainable development of the community.

5. Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

The conclusion from the surveys is that there are perceived business opportunities in rural areas for experienced 50+ professionals. In each of the target countries, almost all of the potential 50+ entrepreneurs already had a lot of the skills that entrepreneurs need, but they also needed to learn from other entrepreneurs in rural areas. In addition, there was a desire for multi-disciplinary learning, consisting of contact learning and online learning, and possibly also some virtual components. There was also a need for one-to-one mentoring, but traditional classroom teaching was not appreciated.

According to previous research and ENTRUST surveys, entrepreneurship training aimed at 50+ entrepreneurs should familiarize them with the kinds of businesses which already exist in rural areas and what kinds of businesses are needed there. In addition, they wanted to learn about what should be considered in sustainable tourism and how to create a sustainable tourism business from rural cultural heritage. It was also important that the training could give them an opportunity to concretely try out, in practice, how to turn an idea into a commercial product or service. The ENTRUST Project has already started the planning of the actual contents of the training based on the literature review and the results of the surveys and will continue to test different options through external expert panels.

Short documentary films were constructed based on the interviewed 50+ entrepreneurs who find their work in rural areas to be meaningful and want to continue working as long as their health allows. They value the development of the region and the preservation of its historical and cultural heritage. For them, it is important that the next generation can also live and enjoy the richness of the countryside. The 50+ entrepreneurs interviewed see cooperation with other local entrepreneurs and producers as an important way of creating a sustainable experience for tourists. When customers enjoy their stay, they return and bring economic growth to the region. This may also attract young people to work or stay in the area. The 50+ entrepreneurs interviewed want rural areas to be strengthened in a way that balances the economic, social and environmental aspects of sustainable development.

5.2. Contribution of the Study

First, the studies carried out alongside the ENTRUST project produced valuable practical information for entrepreneurship education, i.e., constructing the training programme for potential 50+ entrepreneurs. The results show that there is a clear lack of training for 50+ entrepreneurs; interviews with experts revealed that the level of education of rural tourism entrepreneurs is low; therefore, there is a high demand for training.

Training should in fact be targeted at urban residents; for example, those who return to the area of their birth and change careers or retirees who want to move to the countryside. With the training produced by the ENTRUST project, vocational education and training providers (VET) can train 50+ potential entrepreneurs, providing them with practical tools for the sustainable development of rural areas and rural tourism.

According to the OECD and the European Commission [81] (p. 156), barriers to entrepreneurship for seniors often include health issues, the opportunity cost of time and the shorter timeline to grow a sustainable business, and neither a “fear of failure” nor a perceived lack of entrepreneurship skills appear to be disproportionate barriers to business creation for seniors. Based on the results of the ENTRUST studies, potential 50+ entrepreneurs have competencies that they can implement as entrepreneurs, but they needed reflection opportunities, mentoring networks and information about organizations that support rural entrepreneurship.

Both based on our results and referring to Socci, Clarke and Principi’s (2020) [53] research, we state that catalyzing the active potential of older people for the benefit of European local communities is an important driver to solve local economic, societal and environmental problems at the European level.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

The qualitative data of this study consisted of eight interviews, which is a very small sample of individual entrepreneurs. According to Dana and Dana [77] (p. 84), qualitative research need not have a large sample. The limitation, however, is that whereas a small sample may yield high internal validity, its external validity may be limited. Small-numbers research cannot claim to provide statistical generalizations or “proof” of a theory; it can, by assuming that people are not entirely unique, generate significant descriptions about complex processes and relationships [82] (p. 290). This does not mean that data analysis is based on speculation or on vague impressions. The analysis can be systematic and logically rigorous, although in a different way from quantitative or statistical analysis [83] (p. 417).

As the study is partly based on data and literature collected during the Erasmus+ ENTRUST project, the starting point of the research is practical, and the theoretical discussion is perhaps not as in-depth as it could be.

5.4. Further Research

Matthews and Santos [84] state that despite the ongoing challenges and issues facing entrepreneurship as a discipline in general and entrepreneurship education in particular, entrepreneurship is respected as a key aspect of social and economic development and growth. According to the OECD and the European Commission [81] (p. 156), self-employed seniors are slightly more likely to have employees than the overall average. It will be important to look for ways to sustain these businesses and jobs—a project which needs deeper research on 50+ entrepreneurs’ motives, needs and desires concerning their entrepreneurship. Moreover, Ratten [85] emphasizes that there needs to be more entrepreneurship studies that incorporate older people as their subject participants to get a more comprehensive understanding of the role older people play in entrepreneurship.

In our research, we found that there is also a need to consider the regional differences of European countries (e.g., the differences between rural areas such as sparsely populated northern Finland vs. densely populated Netherlands) and what those differences mean when considering entrepreneurship training in different areas and in different countries.

To investigate 50+ entrepreneurs in rural areas more broadly in European contexts is important because there might be differences in education, age of retirement, in funding tools, in ways of networking and in ways of starting new businesses, etc. It is important to know the local areas so that the local regional operators, in co-operation with entrepreneurs, can impact the local social environment and economy so that the area will flourish.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R.-P. and M.S.; methodology, T.R.-P.; software, M.S.; validation, T.R.-P. and M.S.; formal analysis, T.R.-P. and M.S.; investigation, T.R.-P. and M.S.; resources, T.R.-P. and M.S.; data curation, T.R.-P. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R.-P. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, T.R.-P. and M.S.; visualization, T.R.-P. and M.S.; supervision, T.R.-P. and M.S.; project administration, T.R.-P.; funding acquisition, T.R.-P. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research data was collected in ENTRUST project that was funded by Erasmus+ Programme 2021–2027, KA2: Cooperation Partnerships/Small Scale Partnerships, grant number 2021-1-IE01-KA220-VET-000025414. And the APC was funded by Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research design of the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and does not require the Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Survey data are maintained according to Erasmus+ requirements and the data are unavailable due to privacy restrictions. The entrepreneurs have undersigned the Declaration for data usage and given permission for the Consortium of the project Erasmus+ to use the provided information for the development of Best Practice and for dissemination purpose.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cela, E.; Ciommi, M. Ageing in a Multicultural Europe: Perspectives and Challenges. In Building Evidence for Active Ageing Policies; Zaidi, A., Harper, S., Howse, K., Lamura, G., Perek-Białas, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2018; pp. 211–237. ISBN 978-981-10-6016-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, J.; Rocco, T. Development of older workers: Revisiting policies. In Cedefop, Working and Ageing: Emerging Theories and Empirical Perspectives; Cedefop; Publications Office of European Union: Luxembourg, 2010; pp. 13–27. ISBN 978-92-896-0629-5. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Population Ageing in Europe: Facts, Implications and Policies, Outcomes of EU-Funded Research. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Socioeconomic Sciences and Humanities. Directorate B—Innovation Union and European Research Area. Unit B.6.—Reflective Societies, 2014; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Rural Development. EU Regional and Urban Development. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/policy/themes/rural-development_en (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Sobczyk, W. Sustainable development of rural areas. Problemy ekorozwoju. Probl. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 9, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Šimková, E. Strategic approaches to rural tourism and sustainable development of rural areas. Agric. Econ. 2007, 53, 263–270. Available online: https://www.agriculturejournals.cz/pdfs/age/2007/06/03.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Entrepreneurs in rural tourism: Do lifestyle motivations contribute to management practices that enhance sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komppula, R. Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A. Mikä on Kirjallisuuskatsaus? Johdatus Kirjallisuuskatsauksen Tyyppeihin ja Hallintotieteellisiin Sovelluksiin. [What Is a Literature Review? An Introduction to the Types and Applications of Literature Review in Management Science]; Opetusjulkaisuja 62; University of Vaasa Publications: Vaasa, Finland, 2011; ISBN 978-952-476-349-3. Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-476-349-3 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Bohlinger, S.; van Loo, J. Lifelong learning for ageing workers to sustain employability and develop personality. In CEDEFOP, Working and Ageing. Emerging Theories and Empirical Perspectives; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010; pp. 28–57. ISBN 978-92-896-0629-5. [Google Scholar]

- Aaltio, I.; Mills, A.J.; Halms Mills, J. Introduction: Why to study ageing in organisations? In Ageing, Organisations and Management; Aaltio, I., Mills, A., Mills, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-58812-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, B.; Mulder, R. A literature review basis for considering a theoretical framework on older workers’ learning. In Working and Ageing: Emerging Theories and Empirical Perspectives; CEDEFOP Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010; pp. 59–73. ISBN 978-92-896-0629-5. [Google Scholar]

- Isele, E.; Rogoff, E.G. Senior entrepreneurship: The new normal. Public Policy Ageing Rep. 2014, 24, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, N. Starting Up after 50, CELCEE Digest. 2002. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED476585 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Hearn, J.; Parkin, W. Age at Work: Ambiguous Boundaries of Organizations, Organizing and Ageing; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781526427724/9781529739848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schøtt, T.; Rogoff, E.; Errington, M.; Kew, P. GEM Special Report on Senior Entrepreneurship 2016–2017, Global Entrepreneurship Research Association; GEM Consortium: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-93924-208-2. Available online: https://gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2016-2017-report-on-senior-entrepreneurship (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- OECD/EU. The Missing Entrepreneurs 2019; Policies for inclusive entrepreneurship; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järnefelt, N. Ikääntyneiden yrittäjyys on lisääntynyt. [Entrepreneurship among older people has increased]. Hyvinvointikatsaus 2011, 4. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/tup/hyvinvointikatsaus/hyka_2011_04.html (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Sutela, H.; Pärnänen, A. YRITTÄJÄT SUOMESSA 2017. [Entrepreneurs in Finland], Statistics Finland, Helsinki. 2018. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/tup/julkaisut/tiedostot/julkaisuluettelo/ytym_201700_2018_21465_net.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Kautonen, T. Understanding the older entrepreneur: Comparing third age and prime age entrepreneurs in Finland. Int. J. Bus. Sci. Appl. Manag. 2008, 3, 3–13. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190597 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Lechner, C.; Dowling, M. Firm networks: External relationships as sources for the growth and competitiveness of entrepreneurial firms. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2003, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E.; Wainwright, T.; Kautonen, T.; Blackburn, R.A. (Work) Life after Work?: Older Entrepreneurship in London—Motivations and Barriers; SBRC; Kingston University: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-902425-09-2. Available online: https://eprints.kingston.ac.uk/id/eprint/22163/1/Wainwright-T-22163.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Singh, G.; DeNoble, A. Early retirees as the next generation of entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 27, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, P.; Schaper, M. Understanding the grey entrepreneur: A review of the literature. In Proceedings of the Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand 16th Annual Conference, Ballarat, VIC, Australia, 28 September–1 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kautonen, T. Senior Entrepreneurship. A Background Paper for the OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs and Local Development, OECD. 2013. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/senior_bp_final.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Khan, H. Five Hours a Day Systemic Innovation for an Ageing Population. Nesta 2013. Available online: https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/five_hours_a_day_jan13.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Battisto, J.; Kramer Mills, C.; Brown, F.; Weinstock, S. State of the Older Entrepreneur during COVID-19. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 2021. Available online: https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/FedSmallBusiness/files/2021/45-entrepreneuers-aarp-report (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Love, J. Assessing the Needs of Small Business Owners 50+; AARP Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrö, P.; Moisala, A.; Nyrhinen, S.; Levikari, N. Kohti Joustavia Senioriyrittäjyyden Polkuja. [Towards Flexible Pathways for Senior Entrepreneurship]. Raportti Oma Projekti—Seniorina yrittäjäksi-tutkimushankkeesta [Report on the My Project—As a Senior as an Entrepreneur Research Project], Pienyrityskeskus; Aalto-Yliopiston Julkaisusarja KAUPPA + TALOUS; Aalto University: Helsinki, Finland, 2012; Volume 1, ISBN 978-952-60-4751-5 (printed)/978-952-60-4752-2 (pdf). Available online: http://epub.lib.aalto.fi/pdf/hseother/Aalto_Report_KT_2012_001.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Yaniv, E.; Brock, D. Reluctant entrepreneurs: Why they do it and how they do it. Ivey Bus. J. 2012, 76, 1–5. Available online: https://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/reluctant-entrepreneurs-why-they-do-it-and-how-they-do-it/ (accessed on 3 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Valentino, A. Global Family Business Survey. The Impact of Changing Demographics on Family Business Succession Planning and Governance. STEP Project & KPMG Enterprise. 2019. Available online: https://spgcfb.org/2019 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Escuder-Mollon, P.; Esteller-Curto, R.; Ochoa, L.; Bardus, M. Impact on Senior Learners’ Quality of Life through Lifelong Learning. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 131, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomin, O.; Janssen, F.; Guyot, J.-L.; Lohest, O. Opportunity and/or Necessity Entrepreneurship? The Impact of Socio-Economic Characteristics of Entrepreneurs; MPRA Paper no. 29506; University of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2011; Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/29506/2/MPRA_paper_29506.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Römer-Paakkanen, T.; Takanen-Körperich, P. Women’s entrepreneurship at an older age: Women linguists’ hybrid. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 17, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allardt, E. Hyvinvoinnin ulottuvuuksia. In Dimensions of Wellbeing; WSOY: Juva, Finland, 1976; ISBN 9510074055/9789510074053. [Google Scholar]

- Raivio, H.; Karjalainen, J. Osallisuus ei ole keino tai väline, palvelut ovat! Osallisuuden rakentuminen 2010-luvun tavoite- ja toimintaohjelmissa. [Inclusion is not a means or a tool, services are! Building inclusion in the 2010s’ target and action programmes]. In Osallisuus—Oikeutta vai Pakkoa? Era, T., Ed.; [Participation—Right or compulsion?], Jyväskylä University of Applied Sciences, publications 156; Jyväskylä University of Applied Sciences: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2001; Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-830-280-6 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Advances and Open Questions in the Science of Subjective Well-Being. Collabra Psychol. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, A.; Corrado, L. No Man Is an Island: The Inter-Personal Determinants of Regional Well-Being in Europe. Cambridge; Working Papers in Economics 0717; Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Regional Well-Being: A Closer Measure of Life. A User’s Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.oecdregionalwellbeing.org/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Wiklund, J.; Nikolaev, B.; Shir, N.; Foo, M.-D.; Bradley, S. Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M. Switching to self-employment can be good for your health. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 664–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Halvorsen, C.; Minniti, M.; Kibler, E. Transitions to entrepreneurship, self-realization, and prolonged working careers: Insights from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2023, 19, R713–R715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. Proposal for a Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. 2005. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52005PC0548&from=ES (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Schmidt-Hertha, B.; Krašovec, S.J.; Formosa, M. Introduction: Older Adult Education and Intergenerational Learning. In Learning across Generations in Europe: Contemporary Issues in Older Adult Education; Research on the education and learning of adults; Schmidt-Hertha, B., Krašovec, S.J., Formosa, M., Eds.; Sense Publisher: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-94-6209-900-5/978-94-6209-901-2/978-94-6209-902-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, D. Entrepreneurship from Opportunity to Action; Palgrave McMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 10-1403941750. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, A.A. The future of entrepreneurship education-determining the basis for coherent policy and practice? In The Dynamics of Learning Entrepreneurship in a Cross-Cultural University Context; Kyrö, P., Carrier, C., Eds.; University of Tampere: Hämeenlinna, Finland, 2005; ISBN 951-44-6379-X. [Google Scholar]

- Pittaway, L.; Cope, J. Stimulating entrepreneurial learning: Integrating experiential and collaborative approaches to learning. Manag. Learn. 2005, 38, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, D. Yliopistot ja yrittäjyyskasvatus: Vastaus uuden aikakauden haasteisiin [Universities and entrepreneurship education: A response to the challenges of the new era]. In Yrittäjämäinen oppiminen: Tavoitteita, toimintaa ja tuloksia [Entrepreneurial Learning: Goals, Activities and Results]; Heinonen, J., Hytti, U., Tiikkala, A., Eds.; University of Turku: Turku, Finland, 2011; ISBN 978-952-249-152-7. [Google Scholar]

- De Faoite, D.; Henry, C.; Johnston, K.; van der Sijde, P. Education and training for entrepreneurs: A consideration of initiatives in Ireland and The Netherlands. Educ. Train. 2003, 45, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, D. Conceptual Basis for Learning. Frameworks for Older Adult Learning. In Learning across Generations in Europe: Contemporary Issues in Older Adult Education; Research on the Education and Learning of Adults; Schmidt-Hertha, B., Krašovec, S.J., Formosa, M., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 73–84. ISBN 978-94-6209-901-2/978-94-6209-900-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kickul, J.; Fayolle, A. Cornerstones of change: Revisiting and challenging new perspectives on research in entrepreneurship education. In Handbook of Research in Entrepreneurship Education, A General Perspective; Fayolle, A., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-1-84542-106-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hessel, R. Active ageing in a greying society: Training for all ages. Eur. J. Vocat. Train. 2008, 45, 144–163. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.550.5167&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Formosa, M. Lifelong Learning in Later Life: Policies and Practices. In Learning across Generations in Europe: Contemporary Issues in Older Adult Education; Schmidt-Hertha, B., Krašovec, S.J., Formosa, M., Eds.; The European Society for Research on the Education of Adults (ESREA); Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 11–22. ISBN 978-94-6209-900-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socci, M.; Clarke, D.; Principi, A. Active Aging: Social Entrepreneuring in Local Communities of Five European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desjardins, R.; Rubenson, K. Participation patterns in adult education: The role of institutions and public policy frameworks in resolving coordination problems. Eur. J. Educ. 2013, 48, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Development and Sustainability. 2022. Available online: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/development-and-sustainability/sustainable-development_en (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantoni, I. A Few Remarks on Methodological Aspects Related to Sustainable Development. In Measuring Sustainable Development: Integrated Economic, Environmental and Social Frameworks; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2004; pp. 63–89. ISBN 92-64-02012-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, D.S.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Antons, D.C.; Munoz, P.; Bai, X.; Fragkia, M.; Gutscher, H. A vision for human well-being: Transition to social sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council. The GSTC Criteria. Available online: https://www.gstcouncil.org/gstc-criteria/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- OECD. OECD Regional Typology. Directorate for Public Governance and Territorial Development. 2011. Available online: www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/OECD_regional_typology_Nov2012.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Lanfranchi, M.; Giannetto, C. Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: The New Model of Social Farming. In Competitiveness of Agro-Food and Environmental Economy (CAFEE’12). 1st International Conference ‘Competitiveness of Agro-Food and Environmental Economy’. 2012. Volume 1. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2284076 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- World Tourism Organization. UNWTO Recommendations on Tourism and Rural Development—A Guide to Making Tourism an Effective Tool for Rural Development; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2020; eISBN 978-92-844-2217-3/978-92-844-2216-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana, M.-I. Ecotourism, Agro-tourism and rural tourism in the European Union. Cactus Tour. J. 2017, 15, 6–14. Available online: https://www.cactus-journal-of-tourism.ase.ro/Pdf/vol16/1.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Arslan, M.; Ekran, E. Importance of rural tourism and investigation of abroad examples. In Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific Africulture Symposium, Jahorina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 5–8 October 2017; pp. 2579–2584. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323174930_IMPORTANCE_OF_RURAL_TOURISM_AND_INVESTIGATION_OF_ABROAD_EXAMPLES (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Soykan, F. Kırsal Turizmin Sosyo- Ekonomik Etkilerive Türkiye, Türkiye Dağları I. In Proceedings of the Ulusal Sempozyumu, Ankara, Turkey, 25–27 June 2002; Orman Bakanlığı Yayın No: 183. Orman Bakanlığı Araştırma Planlama ve Koordinasyon Kurulu Başkanlığı: Ankara, Turkey, 2002. [Socio-Economic Impacts of Rural Tourism in Turkey, Turkey Mountains I. In Proceedings of the National Symposium, 25–27 June 2002; Ministry of Forestry Publication No: 183; Ministry of Forestry Research Planning and Coordination Board: Ankara, Turkey, 2002]. [Google Scholar]

- Tourism Notes. Rural Tourism—Definitions, Types, Forms and Characteristics. 2022. Available online: https://tourismnotes.com/rural-tourism/ (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Fleicher, A.; Pizam, A. Rural tourism in Israel. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 367–372. Available online: https://www.institutobrasilrural.org.br/download/20080611131755.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kastenholza, E.; Carneiroa, M.J.; Marques, C.P.; Lima, J. Understanding and managing the rural tourism experience—The case of a historic village in Portugal. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2022; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; ISBN 978-92-64-48095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture for Development Indicators. Methodology Manual. 2014. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/creativity/sites/creativity/files/cdis_methodology_manual_0_0.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- UNESCO. World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme. 2022. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-669-7.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Timmermans, S.; Tavory, I. Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociol. Theory 2012, 30, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, L.P.; Dana, T.E. Expanding the scope of methodologies used in entrepreneurship research. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2005, 2, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, L. Why might you use narrative methodology? A story about narrative. Eest. Haridusteaduste Ajak. 2016, 4, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]