Abstract

In this paper, we review the EU and national (Croatian) education policy trends related to life-long learning and adult education in the last five years, focusing on the subsequent crises (COVID-19 and the security crisis caused by the war in Ukraine) and their influence on policy processes and documents. We also provide secondary data on trends in Croatian adult education, as well as present the results of empirical research performed on a sample of adult education providers from the Republic of Croatia. Our research aimed to identify how the policy trends have been reflected in the practice of Croatian adult education providers in the last five years (2018–2022), with the focus on (a) the practice of life-long learning and adult education promotion; (b) target groups for adult education providers in Croatia; and (c) how the institutional infrastructure in Croatia has supported adult education providers. The obtained results inform the policymakers and practitioners of adult education of potential discrepancies between policy trends and education practices relevant to small and peripheral EU member countries.

1. Introduction

Adult education in Croatia is based on the concept of life-long learning. Formal adult education is recognized as part of the education system of the Republic of Croatia. Its roots reach back to the beginning of the 20th century, with significant contributions to the concept of andragogy since the 1950s [1]. Currently, adult education is considered to be a part of the life-long learning system and defined consequently by a legal framework, being carried out as formal and informal education, as well as by acquiring knowledge and skills through informal learning.

Within the formal system of adult education in Croatia, primary education and all forms of secondary education for adults are carried out, as well as various training programs and specialist training programs that can be acquired as complete, partial, or micro-qualifications. Institutions established as adult education providers are responsible for implementing these types of programs. The Croatian Adult Education Act is competent up to level 5 of the National Qualification Framework (CROQF). In contrast, adult education from level 6 and above, according to the CROQF, is conducted by universities and can be formal or informal. Non-formal education, as well as informal learning, are primarily not regulated within the formal adult education system, except for the part of the evaluation program that enables the recognition of previously acquired knowledge and skills, which can be acquired through formal, non-formalor informal means [2].

The introduction of the evaluation programs is one of the critical steps forward in developing the adult education system, especially intending to create prerequisites for citizens to certify all the knowledge, skills, and experience.

A particular novelty is that the Republic of Croatia has introduced a system of vouchers for adult education, through which citizens’ education will be financed from different sources and for different types and forms of programs. To the greatest extent, it will be completely free. Furthermore, in the Croatian system of adult education, various forms of informal and non-vocational education for personal development and activity in the community are created (programs of creative workshops, socio-cultural activity, and strengthening of social skills), and providers most often implement them as forms of adult education or in cooperation with various organizations from the non-profit sector. The new Adult Education Act introduced a whole series of novelties into the adult education system, especially in program development and implementation, as well as in establishing the quality assurance system, based on predetermined standards and external evaluation procedures, preceded by institutional self-evaluation.

In the last eight years, the critical basis for the development of the adult education system was the Education, Science, and Technology Development Strategy from 2014 [3]. In the strategy, the entire education system is based on life-long learning, with adult education serving as a significant lever. The strategy defines the instruments intended to improve the adult education system, increase the participation of citizens, and ensure the quality of education. For this reason, it envisages measures for the development of a system of life-long professional development and licensing of andragogicprofesssionals. This includes the development of qualification standards for andragogic professionals. It is planned to implement a program for andragogic and professional life-long education and training of adult education providers.

The entire Education Development Strategy is closely linked to the implementation of the CROQF, which affects its understanding. The learning outcomes must correspond to the labor market’s needs, which are to be decided by experts in councils formed by the business sector. The social dimension and inclusiveness of education are an addition to the primary task. Additional stimulus for the development of the adult education system were various projects financed by European Union programs, especially the European Social Fund and Erasmus, implemented by ministries and education agencies such as the Agency for Vocational Education and Adult Education (AVETAE), institutions for adult education, associations, professional associations, employers, organizations, and units of local and regional administration and self-government.

These projects represent a critical factor in the development, innovation, and improvement of the entire adult education system.

The new foundation for the development of the adult education system, as well as the entire system of education and life-long learning, is determined by a significant national document, the National Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia until 2030 [4], which states that the quality of and participation in life-long learning are essential for the success of the Croatian education system.

The Program of the Government of the Republic of Croatia 2020–2024 [5], which refers to the continuation of the innovation and development of the adult education system, serves as a further elaboration and the basis for achieving the previously mentioned goals.

The importance of life-long education, and the necessity of its improvement and promotion, and the Implementation Program of the Ministry of Science and Education 2021–2024 [6] refer to the need to invest further efforts in the direction of the development of a quality assurance system in adult education.

One of these essential measures is financing adult education programs for citizens, which has already been addressed through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan [7], as stated in chapter C3.1. In the reform of the education system, one of the goals is “to reverse the trend of low participation in life-long adult education” [7] (p. 858). The described policy framework led to a successfully established system of vouchers for adult education that citizens can use for free, which is currently being successfully implemented in the Republic of Croatia.

These documents and activities have their foundation and origin in key European and international documents, such as the Resolution of the Council of the European Union on the New European Agenda for Adult Learning 2021–2030 [8], which calls on member states to carry out activities aimed at the further development of quality assurance mechanisms in the field of learning and adult education and emphasizes the critical role of strengthening the awareness of the importance and benefits of participation in life-long learning. In addition, and the Recommendation of the Council of the European Union on Upskilling Pathways-New Opportunities for Adults [9] focuses on the importance of quality in adult education, emphasizing that a quality learning offer should be one of the foundations of the training of adults, as well as informing them about learning opportunities.

One of the most recent documents is the Final Document of UNESCO’s Seventh International Conference on Adult Education, i.e., the Marrakesh Framework for Action [10], which places the creation of a culture of life-long learning at the center of future development activities. In contrast, strengthening institutional capacities for promoting life-long learning is listed as one of the paths to its realization.

2. Priorities in EU and Croatian Adult Education Policies (2018–2022)

Croatia has been an EU member state since 2013, becoming fully integrated into the Eurozone and the Schengen system as of 2023. Although there is no centralized education policy on the EU level, national policies are subjected to the ‘open method of coordination’ (OMC), as a ‘soft’ tool for individual member states to reach policy objectives, set by the consensus of member states and the EU Commission, as well as to establish joint measurement instruments, benchmarking processes, and the exchange of best practices at the EU level [11].

The high levels of policy learning and the political imperatives of ‘Europeanization’ [12] are fostered by the benchmarking exercises and rankings of the national EU education systems and their performance [13]. Therefore, there is a tangible shift toward more integrated, trans-governmental policymaking in EU education policies, based on economic and functional objectives [14], including competitiveness and economic performance. In this context, the life-long learning educational policies and practices in Croatia are highly influenced by EU policies and benchmarks, especially with the direct financing of life-long learners by means of micro-qualification vouchers.

Therefore, Croatian life-long learning and adult learning policy and practice landscape(s) need to be considered in the EU context, especially since Croatia is constantly and significantly lagging behind the EU average when it comes to the levels of adult participation in life-long education and learning (see Section 4 of this paper).

In addition, specific circumstances have been introduced by a range of crises, shaping the European socio-economic environment. Those include the COVID-19 pandemic, the ongoing war in Ukraine, the rise in inflation, and other factors [15] contributing to high levels of uncertainty in the educational environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the forms of implementation of adult education. This is related to the economic consequences of the pandemic and the effort to ensure recovery. In addition to the health, social, and economic consequences of the pandemic, there were significant changes in the implementation of education, teaching methods, and the involvement of students. The space and time of education are changing significantly [16]. The pandemic was followed by the crisis caused by the war in Ukraine and the associated security, energy, and financial challenges and other challenges. The central part of Croatia also faced the consequences of two earthquakes in 2020.

An extensive analysis of changes in adult education policies in the European Union was made on the Eurydice platform [17]. The OECD also conducted a significant study [18], focusing on skill gaps among workers observed during the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated crisis. New priorities in adult education were analyzed, especially the role of micro-qualifications.

European and global challenges have encouraged a new definition of the goals of adult education. At the global level, the recommendations from Marrakech given by CONFINTEA VII [18] are essential. The recommendations refer to changes in adult education and training that advocate the creation of a culture of life-long learning adapted to each member state. Therefore, these changes in administrative arrangements have an impact on the entire system of values. The changes include new forms of public management and the redesign of the adult education system, which would define it as a public and common good within public education. The importance of quality teachers, engagement of all platforms and places for adult learning, and the creation of flexible learning paths were emphasized. The importance of evaluation and public recognition of non-formal and informal learning was reiterated. It insists on ensuring the quality of learning, increasing public funding, and preventing the reduction of existing budget allocations.

At the EU level, the critical document for positioning life-long learning is the European Pillar of Social Rights [19]. The European Pillar of Social Rights from 2017, as the basis of current social and economic policies, already in its first sentence, indicates the importance of life-long learning. In line with the primary goal of the European Pillar of Social Rights action plan, 60% of all adults should participate in training each year by 2030. The European Skills Agenda 2020 [20] emphasizes the importance of life and vocational skills. Introducing individual learning accounts (including learning vouchers) and micro-qualifications for life-long learning and employability are critical activities in the European Skills Program. Adult learning has been identified as the main topic of the European Education Area for the period 2021–2030.

An important educational, economic, and social goal is to create better opportunities for the inclusion of individuals in life-long learning. In the period after 2020, this includes two critical tools: individual learning accounts and the introduction of micro-qualifications. Individual learning accounts are mentioned as a priority in several European documents. These include the European Skills Agenda 2020, The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan (2021) [21], and the 2021 Commission Proposal with Council Recommendations on Individual Learning Accounts [22] setting the policy for implementation of micro-qualifications.

The Resolution on the New European Agenda for Adult Learning [8], adopted by the Council of the European Union in 2021 is crucial for adult education. This program emphasizes the need for a significant increase in the participation of adults in formal, non-formal, and informal learning. In this European program for the development of adult education, the importance of acquiring skills related to work and civic and personal development is emphasized.

This European strategic document outlines how adult education should develop in Europe until 2030. There are five priority areas:

- Managing adult learning–with a strong focus on national whole-of-government strategies and developing partnerships with key stakeholders;

- Offering and using life-long learning opportunities with sustainable funding;

- Accessibility and flexibility–adapting to the needs of an adult;

- Quality, equity, inclusion, and success in adult learning—with an emphasis on the professional development of adult education staff, student and staff mobility, quality assurance, and active support for disadvantaged groups;

- Green and digital transitions with the strengthening of the necessary skills for these transitions.

The focus on green and digital skills is present in as early as the December 2016 EU Council Recommendations on Upskilling Pathways: New Opportunities for Adults [23]. Finally, in the 2020 European Skills Agenda [13], green and digital skills have been placed into focus.

In the National Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia until 2030 [4], an important goal is to improve the quality of the work of vocational schools and further develop the regional centers of competence. This includes the open school access to employed and unemployed adults. One of the key goals is to increase the share of the adult population that participates in life-long learning processes as to increase the productivity and quality of the workforce and the ability to adapt to rapid changes. The goal is to reach the EU average in adult participation. Such an ambitious plan should double the participation of adults. It is assumed that support for achieving these goals will be strengthened with a particular emphasis on people who have difficulties accessing education and entrepreneurial and digital skills. Attention is focused on the young people who are not employed and are not in the process of education or training (NEET).

Increasing adult participation is an important goal of the National Recovery and Resilience Program 2021–2027 [7]. The low rate of participation in adult education programs is a significant challenge in Croatia. Therefore, life-long learning programs need to continue improving their quality and relevance, while the recognition of informally and informally acquired knowledge and skills is to be finally introduced.

Crises are an essential stimulus for determining further directions of development. A series of crises have shown the unpredictability of social, economic, and security circumstances, so further activities will be carried out in an uncertain future in circumstances that we cannot accurately predict. Accordingly, the Development Strategy of Croatia until 2030 [4] refers to life-long learning to facilitate adaptation to unpredictable future and rapid changes due to various crises and unexpected situations while defining the goals presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outcome indicators in adult education.

Participation rate in education and training (last four weeks) by gender and age shows that the situation in Croatia is still significantly below the European average. In 2021, 5.1% of adults (25–64) were involved in some form of education or learning, while at the level of the European Union, this percentage was 10.8%. However, Croatia has already reached the goal set by 2027.

All these global European and national priorities point to several essential starting points of current European policies in adult education:

- The crises in the last few years have opened up changes in priorities in adult education and change in priority rankings.

- Uncertainty, to be accounted for by policy actors, is an essential feature of the environment in which adult education will be conducted.

- Promotional activities have clearly defined priority areas related to green and digital transformation. However, this list is not definitive, as the policy priorities are intertwined with the goals that should respond to social and health challenges.

- At the national level, the achievement of these goals is associated with an increase in the participation of adults in education programs and learning processes, which is the assumption for the achievement of other goals.

- Participation should be increased in all forms of adult education from vocational to general education, from education for smaller groups of learning that acquire micro-qualifications to more extensive programs, and from formal programs to all forms of informal education.

- It is crucial to include individuals and groups who participate less in life-long learning and who have been underrepresented in the learning processes so far.

- National goals are linked to European processes and adult education internationalization, including common European goals, success criteria, means, and experiences (mobility through the Erasmus program).

3. Changes in Adult Education Policies and Practices in Crisis Circumstances

The professional and scientific community has been dealing with adult education participation since the beginning of adult education research [24]. One of the reasons is the effort to provide a new educational opportunity to the excluded, the poor, the uneducated, and the neglected. In the search for equal educational opportunities, the most common approach is one that seeks to remove obstacles that lead to unequal participation in education [25]. These are situational barriers (those arising from one’s life situation), institutional barriers (practices and procedures that hinder participation), and dispositional barriers (personal barriers that include negative attitudes and lack of motivation to involve individuals in learning).

Uncertainties and fears present in crises can be an incentive to solve social problems [26]. However, crises can also block adults and make some changes, adaptations, or inclusion in adult education difficult [27]. The crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has stimulated research that can also be used for subsequent crises. The problem in education research in times of crisis is that it is an ongoing process and in which circumstances, consequences, instruments, and actors are changing [28]. This problem is visible in two editorials by Milana, Hodge, Holford, Waller, and Webb [29,30]. Research has to be constantly updated with new situations, priorities, and analysis results.

James and Thériault [31] analyzed the impact of the current crises on inequalities in adult education. Disadvantaged families had or have limited access to equipment or connectivity and cannot take advantage of online and digital learning. Adults suddenly faced unemployment and had to put immediate earnings ahead of learning and training by working longer hours and taking on additional jobs to provide the necessary household income. This depiction of adult education in uncertain times is not reduced to people with disabilities, the long-term unemployed, or immigrants but includes a broader group of vulnerable people. A shocking question shows this uncertain future in a well-read international journal on adult education: is it time to start talking about the future of adult education as a utopia or in the context of a dystopia [32]?

Based on previous research, several groups have been identified with difficulty accessing adult education programs due to these obstacles. These are people with disabilities, ethnic, national, and religious minorities, people from rural areas, migrants, asylum seekers, people under subsidiary protection, older adults, less educated people, and people who are not employed and do not participate in educational programs.

UNESCO’s 2019 analysis [33] is a basis for future decisions and solid analytical material for the problem of participation and promotion of adult education. The grounds are global difficulties in implementing education and crises more permanent than the pandemic and the current economic crisis or European security threats. This UNESCO analysis develops a specific typology of adult learning and education. Recognizing that types of adult learning and education vary widely, this analysis groups adult education into three key areas:

- Literacy and essential skills;

- Continuous vocational education and training that is carried out at the workplace and in school and post-school education;

- Liberal, popular, and social education that includes active citizenship skills and political education, health education, culture, and personal development [33], (p. 95).

This policy document mentions women, the rural population, migrants, refugees, older adults, people with disabilities, and less educated adults as excluded groups (pp. 123–152). Although it is a global organization that includes countries with very different economic potentials and educational cultures, the analysis offers a good starting point for further national elaboration. Based on the mentioned analyses and research, the already described obstacles for greater participation of adults are repeated [33], (pp. 153–158):

- Situational obstacles (those arising from one’s situation in life);

- Institutional obstacles (practices and procedures that hinder participation);

- Dispositional barriers (attitudes and tendencies toward learning).

It is important to note that the mentioned obstacles to life-long learning are interconnected and influence each other. Structural conditions such as political structures, rules, and norms regulated by state authorities affect the equality or inequality of participation opportunities and initiate processes of inclusion or exclusion from adult education and learning. People living in poverty or otherwise disadvantaged can hardly even consider participating in adult learning and education. Therefore, institutional barriers influence the belief that disadvantaged people have nothing to gain from learning. A significant part of the population in some countries faces institutional obstacles such as difficult access to educational programs or high costs. This cost is often a significant barrier to participation in education. Institutional adjustments make it easier to overcome dispositional barriers. Adequate financial support to vulnerable groups plays a vital role in reducing institutional and situational obstacles. The possibility of gaining work experience can affect all three categories of barriers. Developing more customized learning assistance can help reduce situational and dispositional barriers. Dominant surveys and statistical data are constructed in a way that does not allow a closer analysis of the role of dispositional barriers, which has severe implications for their utility for evidence-based program development.

From analytical reports and analyses of adult education policies [28], it can be concluded that most of the goals in adult education have remained the same for the last twenty years or they are just modified goals that were already set by the Lisbon process from the 2000s or the Memorandum on life-long learning. In this period, adult education also aims to solve economic and social problems in a balanced way. These fundamental goals are followed by new layers of policies that respond to new crises. The burden of responsibility is transferred to the individual to whom the state provides a quality choice of educational paths through regulatory and incentive tools. An individual learning account is one such tool that should be used to achieve set goals. The model of the qualification framework remains a central structural tool that also contains ideas on the nature and essential features of adult education [28]. Micro-qualifications are a continuation of this idea. The digital and green transition and the skills required for them are not new in the EU, but the focus has been placed on them with a slightly modified policy understanding. They contain both goals (economic and social), and their significant contribution to the recovery after the pandemic crisis is expected. In addition, new educational priorities are emerging arising from social challenges, the energy crisis, new migrant waves, the war in Ukraine, and other environmental trends.

It can be suggested that no radical changes in adult education have emerged from the current crises. New interpretations of the existing goals and instruments appear, and some operational goals are reformulated or positioned at the center of policies. Life-long learning in the knowledge society is still the same dominant discourse, which is now “seasoned” with more present green and digital skills and clear inclusive expectations. The efforts for stronger inclusivity have shown the interconnectedness of the work on different types of adult literacy [34]. It should be also added that excluded or neglected groups are empowered through education [35]. Since the crises are still ongoing and new challenges are emerging (security, energy, etc.), it is not easy to estimate how long this twenty-year continuity will last.

In the analysis of the implementation of adult education policies and the entire adult education system, the time dimension is essential [36,37]. It is precisely the current crises and the challenges they bring that have shown that it is necessary to act quickly and hit the right moment when reacting to a particular problem. If some measures are not timely or take too long, the actual effects will not be achieved.

4. Adult Education in the Republic of Croatia: Key Data, Trends, and Challenges

We can monitor the situation in adult education by analyzing data from Eurostat or national statistics (see Table 2 for Croatian data), which refers to the number of enrolled participants and formal adult education programs that are licensed for implementation. Currently, no data are available for 2022.

Table 2.

Number of enrolled and registered participants in formal adult education programs in Croatia (2018–2021).

The number of registered participants dropped significantly in 2020, which can be explained by the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions introduced to prevent the spread of the disease. The largest number (more than half) of participants participate in training programs (see Table 3), similar to previous years [24].

Table 3.

Number of programs by type of education in Croatia (2022).

Participation is influenced by the shorter duration of the training programs (easier coordination with other obligations), their price, which is lower than the prices of other formal programs, and the ability to react more quickly to educational needs. The fewest adults are involved in primary adult education. This is expected, as the number of adults without a primary school education is falling drastically, and those that do not have a primary school education are getting older, with a significant number no longer of working age. The lack of adaptation of the duration and content of the educational program also discourages those who would like to participate in primary adult education programs [38].

According to Eurostat data, the number of adults participating in education increased significantly in 2021 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of adult participation in education and training (last four weeks).

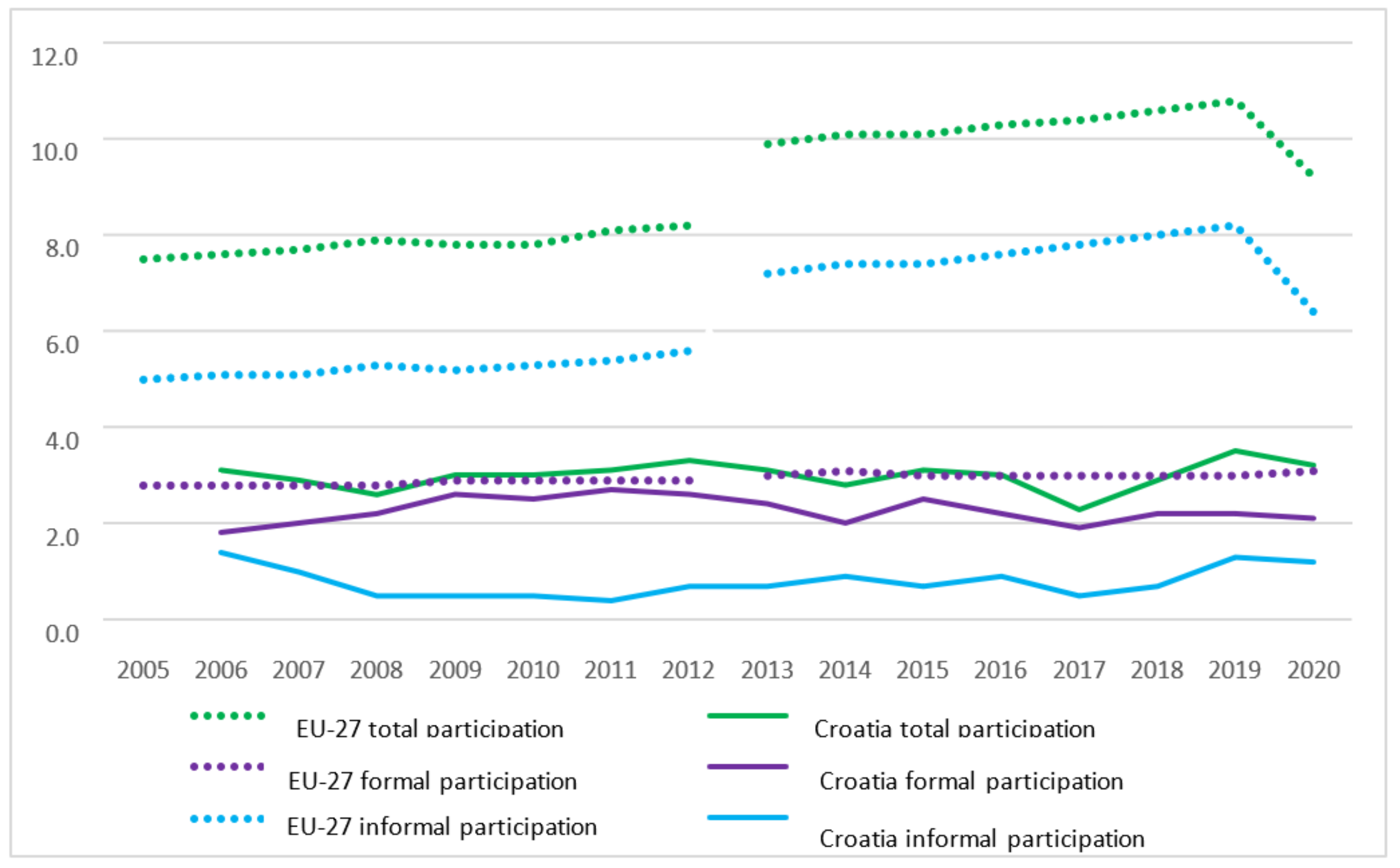

The assumption of Eurostat is that this is a consequence of the re-engagement of adults in education after restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic and incentive instruments for education. The impact of the new law could not yet be seen in that year (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participation of adults (25–64) in life-long learning by type of program, Croatian and EU-27 average. Source: LFS-Eurostat (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TRNG_LFSE_02/default/table?lang=en&category=sks.sks_dev.sks_devlf.trng_lfs_4w0, accessed on 8 December 2022). Consolidated by Matković and Jaklin [39]. Note: The lines are not connected in the years where a break in the series is indicated. Reprinted with permission of authors and journal editors from [39]. Copyright 2023, Hrvatsko andragoško društvo.

It can be concluded that although participation in Croatia has slightly increased over the ten years, almost exclusively in the sphere of informal education, it is still far from the set goal.

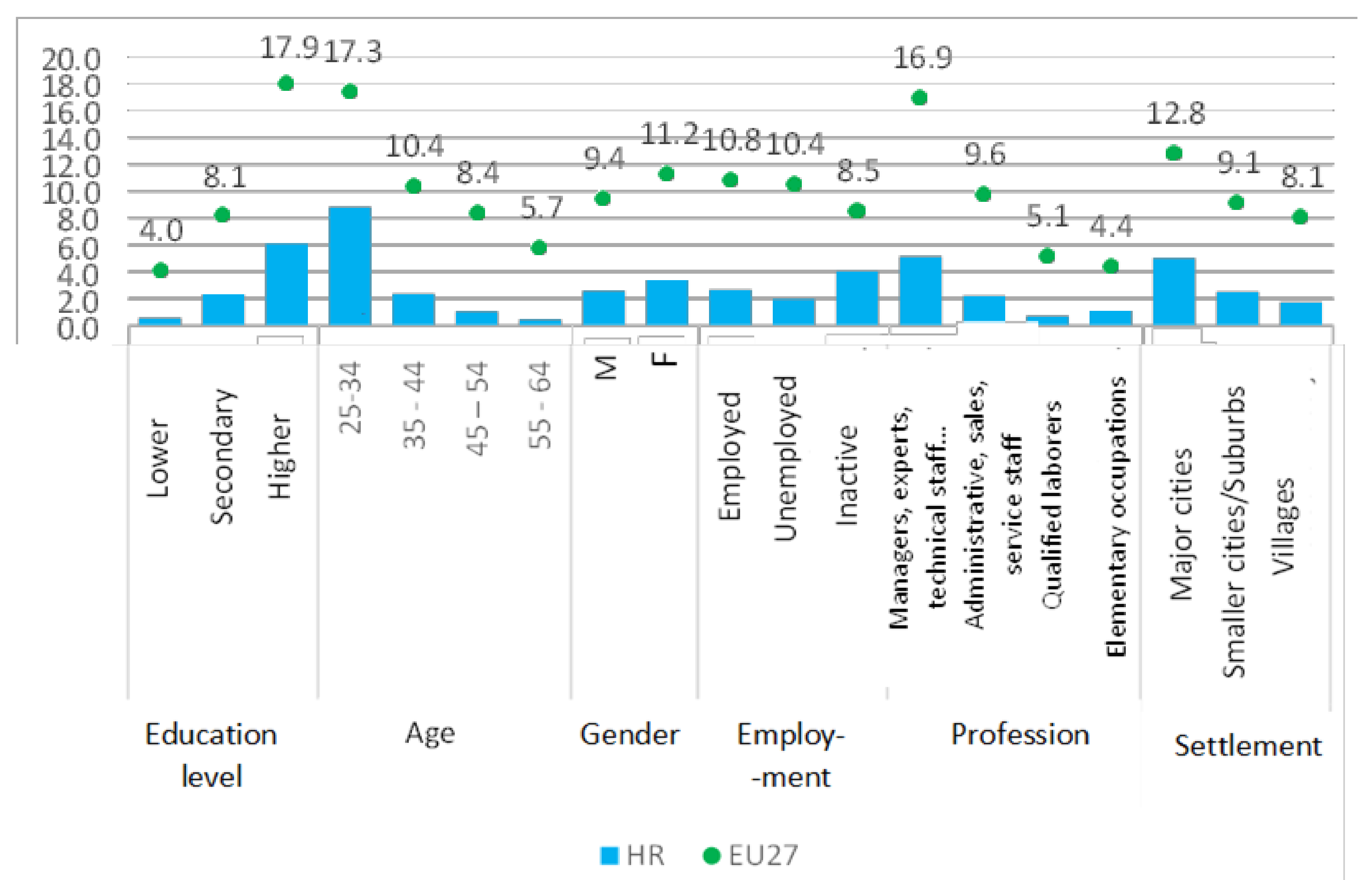

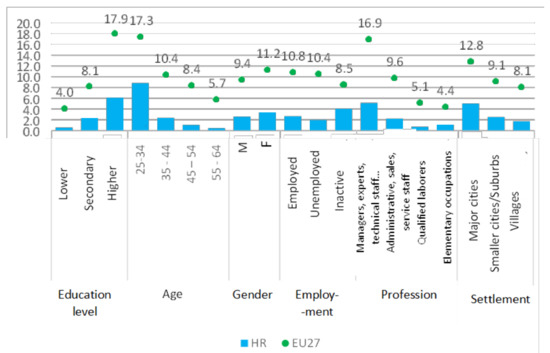

The data relating to obstacles to the inclusion of adults from 2018 are statistical data from Eurostat and the results of qualitative research (focus groups) conducted in 2021 as a part of the Thematic Network Life-long Education Accessible to All project. Within the same project, Matković and Jaklin [39] consolidated Eurostat data on obstacles to inclusion in adult education. Eurostat data show which groups participate less often in adult education. Figure 2 shows the participation of adults regarding gender, age, education, employment status, occupation, and the size of the settlement of education participants.

Figure 2.

Participation in adult education in Croatia and the EU-27 average by the level of education, age, gender, employment status, occupation, and the type of settlement. Source: Matković and Jaklin [39]. Reprinted with permission of authors and journal editors from [39]. Copyright 2023, Hrvatsko andragoško društvo.

Gender differences between male and female participants in adult education are not significantly expressed. According to the Labor Force Survey, the difference is more pronounced at the EU-27 level, while in Croatia, the difference is slightly lower (0.8%). The direction of the difference is different. Women participate more often. To understand those differences, an analysis should be carried out at the type of adult education level since the Labor Force Survey does not cover participation in informal education well.

Age differences are more pronounced. As the age of the participants increases, their participation rate decreases. The younger groups are much closer to the European average than the older ones. The participation of young people is almost eight times higher than the participation of older people. The above can be explained to some extent by the methodology of the Labor Force Survey in Croatia, which includes participation in formal tertiary education after the age of 25, which is relatively high for the youngest age group in Croatia and is found due to the duration of studies. This bias of the Labor Force Survey can explain the larger differences compared to the EU average [39]. Participation in adult education is also strongly determined by the level of education. The highly educated are involved in additional adult education much more often than the less educated.

Figure 2 shows that people outside the labor market lead as related to participation in adult learning. The above results from the questionable inclusion of informal education in the Labor Force Survey and the fact that the inactive persons also include students. In addition, these data are inconsistent with data on the most common providers of education and training services [39] or the AVETAE data. However, this clearly shows that informal education should be considered when looking at adult education.

The analysis of participation regarding the type of occupation shows that in the groups where the participation share is highest (management personnel), Croatia lags the least behind the European average. The difference is more pronounced for workers in simple jobs and manual workers. According to the Labor Force Survey, skilled workers in manual occupations have the lowest participation rate. Potentially, the reason for this is the exclusion of practical training in the workplace from the definition of life-long learning in the Labor Force Survey, which is potentially more present among this group of workers. In addition, we see a lag in the participation in the education of adults from rural settlements compared to those from smaller towns and suburbs, especially behind those from major cities.

These findings follow those of the AVETAE 2017 study, conducted by Vučić et al. [40], which also concludes that people under the age of 40 make up most of the participants in adult education and that highly educated people, employees, and urban populations are overrepresented among the life-long learners [40] (p. 23). In addition, the AVETAE study establishes that people with medium or higher personal incomes are also overrepresented in adult education. This is particularly evident in their participation in informal education, which is information that is missing from the LFS. Therefore, we can conclude that in the education of adults in Croatia, there exists the so-called ‘St. Mathew effect’, stating that groups with a greater need for life-long education participate less [41]. The consequences include an increase in the advantages of groups in a better starting position (younger, highly educated, employed, with higher incomes) and an increase in the disparity between groups.

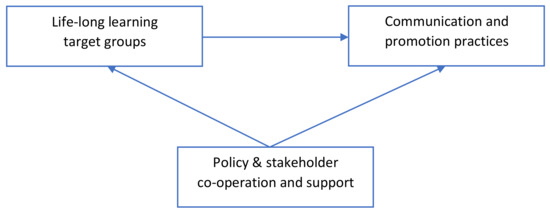

As to overcome the ‘St. Mathew effect’, we focus our interests on the marketing and promotion of life-long learning in Croatia and analyze how the adult education providers chose the target groups for their promotion efforts, which communication practices were used in the life-long learning promotion, and what kind of cooperation and support was available from the policy-making institutions and other stakeholders of the Croatian adult education system.

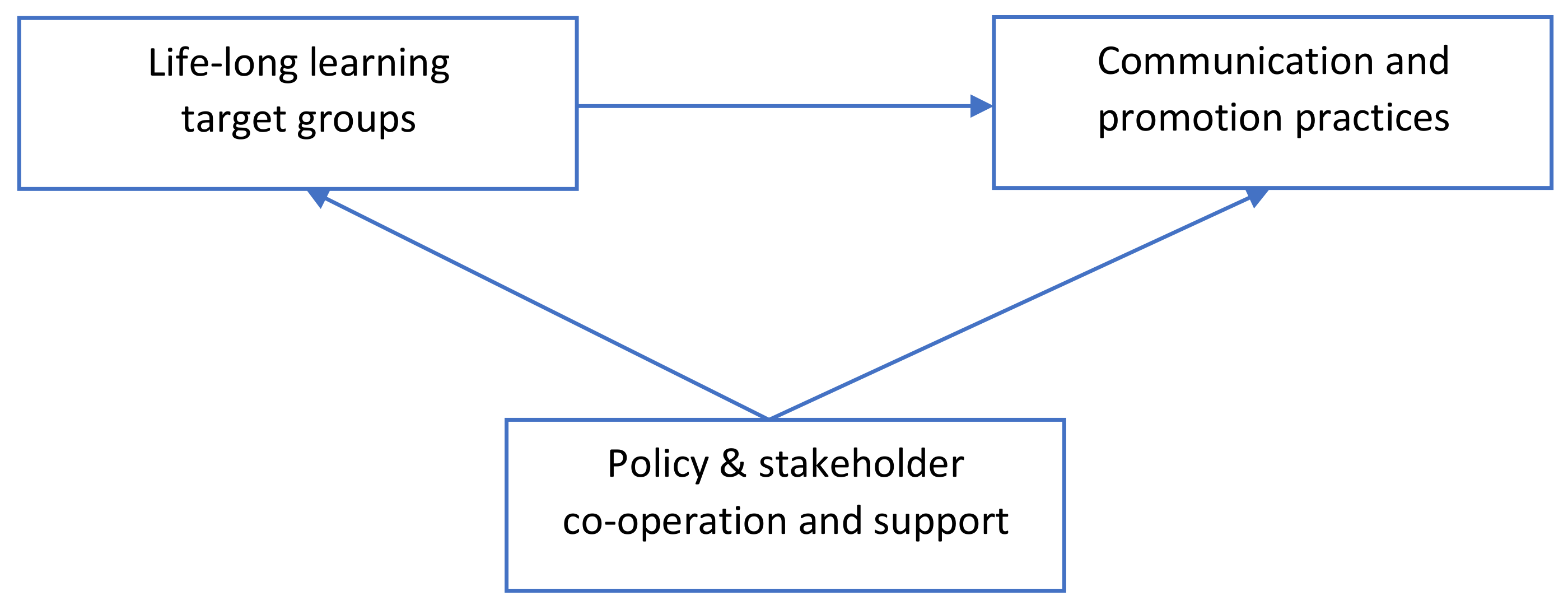

These structural elements make up the conceptual framework for the development of the research questions (see Section 5) and presentation of the empirical research result (see Section 6). Figure 3 visualizes the structure of such a conceptual framework.

Figure 3.

Conceptual model of the empirical research. Source: Authors.

5. Materials and Methods

The secondary data show a significant decrease in the number of students enrolled in adult education programs since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis (2020). Likely, the ongoing economic crisis and the increase in inflation and uncertainty (from 2022) will hurt readiness and opportunities to attend life-long and adult education. In this context, it does not sound encouraging that in 2016–2022, most enrolled adult participants (56%) attended training programs as a form of “education out of necessity” to access more attractive segments of the labor market and solve existential issues.

To determine how the described trends in the EU and national adult education policies are reflected in the practice of adult education service providers in Croatia, an empirical survey was conducted from August to October 2022 aimed at managers of active adult education institutions.

Considering the importance of promoting life-long learning for the practice of adult education service providers [41], the research questions of the empirical research were as follows:

- What were the practices of promoting and communicating adult providers and programs in the 2018–2022 period?

- What were the target groups of adult education in the same period?

- What were the empirical patterns of cooperation and support for the promotion of life-long learning in Croatia, offered by the policy-making institutions and other stakeholders of the adult learning system?

A questionnaire was used as a research instrument, developed by using the key life-long education policy areas, identified in a previous policy document, related to the promotion of life-long learning in Croatia [41,42], as well as the previous empirical research on life-long learning practices, used by the Croatian adult education providers [40]. The questionnaire consisted of several question blocks, describing the following elements of life-long learning promotion and practice:

- Organizational promotion and promotion of life-long learning programs offered on the Croatian educational market;

- Support received from life-long learning stakeholders in Croatia, related to policy issues, development, and promotion of the life-long learning programs;

- Target groups, sources of funding, and communications tools and channels used for organizational promotion and promotion of life-long learning programs;

- Participation in national events for the promotion of life-long learning;

- Required education and support for the development of life-long learning providers’ marketing competencies.

A range of options were offered as potential responses for each of the questionnaire items, with the option for the education provider representative to fill in customized answers, as well. Multiple responses were allowed for each item.

The entire population of registered adult education providers in Croatia was invited to participate in the survey. It consists of 430 adult education providers, registered in the official database maintained by AVETAE.

The questionnaire was distributed to e-mail addresses, registered in the official AVETAE database of Croatian adult education providers. Institution heads (CEOs) were invited to fill in the questionnaire or to delegate the data collection to a person within the organization, most knowledgeable in the topics of life-long education promotion and target group communication practices. To comply with the GDPR legislation, data collection was entirely voluntary and anonymous, without the collection of any personal or demographic details. We are not able to associate individual answers with the person(s) filling in the questionnaire. The participants were also informed their answers should be provided from the institutional perspective, i.e., representing the institutional experience of promoting the life-long learning programs, communicating with the target groups of life-long learners, and obtaining support from the interested stakeholders.

The survey was implemented through the QualtricsXM online data collection platform. A total of 151 fully completed questionnaires were returned, and additional 206 responses on the QualtricsXM platform were recorded, providing only blank questionnaires, or partial answers. Out of those, 102 partially filled questionnaires were usable for further analysis. Therefore, a response rate of 35% was achieved in the data collection stage, which was considered as adequate for further empirical analysis. The statistical processing is based on the maximum available amount of survey data by using the statistical package IBM SPSS.

6. Results

Table 5 shows that as many as 48% of adult education providers tried to deal with institutional promotion to a considerable extent, while only 24.3% neglected the mentioned activity, i.e., they did not perform it at all or only to a lesser extent. The above data are encouraging, but they should also be seen in the context of the number and type of programs, the promotion of which the providers in question paid the most attention.

Table 5.

The practice of institutional promotion of adult education institutions.

Data on the practice of promoting adult education programs are also encouraging, as they largely coincide with the judgment of the overall promotion of adult education service providers (considering that 24.4% of providers did not promote their programs at all or only a little, and 47.8% paid considerable or very considerable attention to the mentioned activity in the observed five-year period). However, it should be noticed that such a high level of matching the perceptions of program and provider promotion may also indicate insufficient differentiation or a misunderstanding of the object of promotion. This issue needs to be further investigated using qualitative methods in future research.

It is also important to point out the structure of the promoted programs. Their focus was placed on training programs, which are attractive on the market, as opposed to the programs, which would contribute to general and civic competencies.

The respondents were offered a choice of one to three options to focus on the promotion of the following types of educational programs:

- Elementary school for adults (5 providers—1.47% of the total of 340 responses received);

- High school for adults (73 providers—21.47%);

- Training programs (112 providers—32.94%);

- Specialist training programs (62 providers—18.24%);

- Programs for acquiring micro-qualifications (22 providers—6.47%);

- Foreign language programs (26 providers—7.65%);

- IT programs (2 providers—0.59%);

- Preparation programs for taking master’s exams (no answers);

- Informal programs—painting, music, etc. (21 providers—6.18%);

- Programs of cultural activities-exhibitions, concerts, etc. (17 providers—5%).

Training and high school graduation programs for adults are preferred, which can be justified as economically viable but not overly clearly connected to the culture of life-long learning. Vocational training programs can also be considered as sufficiently promoted. In contrast, a very weak orientation towards programs for acquiring micro-qualifications is evident, although information is available about the possibility of their co-financing through vouchers.

We also aimed to determine the target groups for adult education institutions’ promotional and communication activities. The respondents were offered the following list of potential target groups, as well as the possibility to identify the additional target group(s), among which they could choose up to three:

- Unemployed adults (93 providers—25.48% of a total of 365 responses received);

- Employed adults (92 providers—25.21%);

- Employed less educated adults—lower and incomplete education (46 providers–12.6%);

- Young people out of employment and education (41 providers—11.23%);

- Unemployed and long-term unemployed adults (33 providers—9.04%);

- Women (24 providers—6.58%);

- People over 50 years old (10 providers—2.74%);

- None of the above (8 providers—2.19%);

- People with disabilities (6 providers—1.64%);

- Roma national minority (6 providers—1.64%);

- Some other groups (foreign languages learners; everyone alike; trainers in sports clubs; young people of school and preschool age…)—6 providers (1.64%);

- Migrants, asylum seekers, and persons under subsidiary protection (no answers).

The surveyed adult education providers mainly focus on vocational training—equally for unemployed and employed people. Of the groups that are in a disadvantageous position for participation in life-long education, particular attention is paid to young people outside the employment and education system (NEET), with 11.23% of the total responses received, as well as to employed persons without completed formal education (12.6%) and unemployed and long-term unemployed adults (9.04%).

Unfortunately, there is non-existent or little attention devoted to the improvement of life-long education opportunities for groups including women (6.58% of the total responses received), people with disabilities (1.64%), Roma (1.64%), and migrants/asylum seekers (no responses received). A small number of adult education providers are still not familiar with the fundamentals of the marketing approach in terms of segmentation and targeting, so they express their focus on “all” (target groups) or “everyone equally.”

The promotion and communication practices, used by the adult education providers in the last five years are as follows:

- Informing the public by using their own website—126 providers (22.26%);

- Personal contacts and communication with stakeholders—117 providers (20.67%);

- Direct communication with the potential customers (life-long learners)—111 providers (19.61%);

- Paid promotion in the media—93 providers (16.43%);

- Sales promotion—61 providers (10.78%);

- Public relations—52 providers (9.19%);

- None of the above—6 providers (1.06%).

Another essential issue was related to the orientation of adult education providers toward (potential) institutional partners. Each respondent could choose from one up to three different institutions targeted by promotional activities. The surveyed Croatian adult education providers were primarily oriented toward employers (mentioned by 105 surveyed institutions, which is 30.7%, out of a total of 342 responses received. Other cooperating institutions included:

- The media (75 providers—21.93%);

- Civil society organizations—non-profit associations, foundations, etc. (43 providers—12.57%);

- Decision-makers in education-policy-relevant ministries, educational agencies-AOO, ASOO…, local (self) administration, etc. (42 providers—12.28%);

- Secondary education providers (25 providers—7.31%);

- Elementary education providers (24 providers—7.02%);

- None of the listed providers (15 providers—4.39%);

- Higher education providers (7 providers—2.05%);

- Providers for early and preschool education (4 providers—1.17%);

- Other institutional partners: the Croatian Employment Service (CES) and international educational providers (2 providers—0.58%).

As expected, the most important (potential) partners are employers, given the prevailing orientation of adult education institutions towards market-based programs. Furthermore, to a limited extent, adult education institutions cooperate with the media, civil society, and decision-makers in educational policy. In contrast, there seems to be negligible cooperation with institutions in other educational levels and sectors.

We also analyzed the cooperation in the field of educational policies and support for the development of plans and programs for adult education. Each adult education provider could choose up to three institutions listed in the questionnaire or specify custom answers. Out of a total of 383 responses received, institutions for adult education in the Republic of Croatia recognized the following as cooperating institutions:

- The Agency for Vocational and Adult Education—AVETAE (137 providers—35.77%);

- The Ministry of Science and Education (85 providers—22.19%);

- The Croatian Employment Service—CES (41 providers—10.7%);

- Partnering providers of adult education (34 providers—8.88%);

- Local administration (17 providers—4.44%);

- None of the specified institutions (14 providers—3.66%);

- The Agency for Education (12 providers—3.13%);

- The Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy (11 providers—2.87%);

- The Croatian Chamber of Commerce/Crafts (11 providers—2.87%);

- Professional associations (10 providers—2.61%);

- Other providers: national sports federations, local companies, and entrepreneurs—end users of the adult education program (in terms of employment of participants), associations in the field of education, and the Ministry of Tourism and Sports (6 providers—1.57%);

- Local development agencies (4 providers—1.04%);

- The National Center for External Evaluation of Education—NCEEE (1 institution–0.26).

The focus was further placed on support for life-long learning promotion and communication received by the responding adult education providers. In addition to AVETAE, a central national institution focused on support and cooperation with providers of adult education, a significant place among supporting institutions is also occupied by the education ministry (MSE), the national employment office (CES), and partner institutions. In this context, there is a relatively small number of stakeholders in the adult education system and the insufficient inclusion of several other potential stakeholders listed in the recommendations of the Strategic Framework for the Promotion of Life-long Learning in the Republic of Croatia (2017–2021) [42].

The most significant source of support to adult education providers’ promotion and communication is provided by the Agency for Vocational and Adult Education-—AVETAE (which was selected by 79 providers, i.e., 26.3% out of 300 responses received). It is very worrying that, in the next place, none of the proposed (potential) cooperating institutions were recognized since as many as 57 providers (19%) believe that no one was supportive of promoting life-long learning and communicating with the target groups. The third place is taken by the Croatian Employment Service—CES (41 institutions-13.67%). The surveyed institutions, which could be singled out from one to three cooperating institutions in the field of promotion and communication, also mentioned:

- Local government (29 providers—9.67%),

- Partner institutionsfor adult education (18 providers—6%);

- The Ministry of Science and Education—Ministry of Education and Culture (18 providers—6%);

- The Croatian Chamber of Commerce/Crafts (14 providers—4.67%);

- Professional associations (11 providers—3.67%);

- Local development agencies (10 providers—3.33%);

- The Agency for Education—AE (6 providers—2%);

- The Ministry of Labour, Pension System, Family and Social Policy (6 providers—2%);

- Other institutions-local media/entrepreneurs (8 providers–2.67%),

- The National Center for External Evaluation of Education—NCEEE (3 providers–1%).

The research results confirm the limitations in the availability and focus of adult education stakeholders in promoting life-long learning and communication with the target groups. In this context, multiple stakeholders need to be involved in promoting life-long learning, emphasizing private employers, who find it increasingly difficult to find the required workforce within the Republic of Croatia and the wider region.

The respondents were also asked to select up to three options or specify their own choices related to the mechanisms of support received in the last five-year period, focusing on life-long learning promotion. Most of the responding adult education providers (84 respondents, i.e., 26.58% of the total of 316 responses received) specified specialized national conferences and events for adult education providers as helpful (e.g., the International Andragogic Symposium, the Andragogic School, etc.). Conferences and special events organized by national education agencies or government ministries were selected as the second most helpful support mechanism by 69 providers (21.84% of the total responses). The third recognized form of support is the national education campaign Life-long Learning Week, organized by AVETAE (60 institutions, i.e., 18.99%). The following support mechanisms are also mentioned:

- Participation in events organized by professional associations in education (33 providers—10.44%);

- Promotional events for micro-qualifications and educational vouchers (28 providers—8.86%);

- None of the mentioned forms of support (27 providers—8.54%);

- Participation in conferences and events in other sectors—e.g., agriculture, tourism, etc. (14 providers—4.43%);

- Organization of the own conference or a special event (1 institution—0.32%).

Apart from the participation and dissemination of information through expert meetings from the education sector and the national campaign Life-long Learning Week, as the only nationally relevant special event in the field of life-long learning, other forms of cooperation proved to be relatively limited. In this context, in the Croatia adult education sector, support and cooperation are still limited and focused on the traditional mechanisms, which regularly do not extend into project cooperation, or support for the application and implementation of educational projects, with an emphasis on the use of EU funds.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

There are several empirical research results, indicating that, even after the life-long learning policy focused on life-long learning promotion issues and organized national campaigns and events, some Croatian adult education providers still do not differentiate and, sometimes, even misinterpret the object of promoting life-long learning. They still state that ‘everyone equally’ or ‘all target groups’ are being addressed by their promotion efforts. Qualitative methods should be used in future research to obtain a better insight into this dimension of the problem. It is also necessary to further analyze the structure of promoted programs, that is, the focus of institutions on training programs that are attractive to the educational market, as opposed to some other forms of programs, which could contribute to greater extent to building the culture and practice of life-long learning.

Additional limitations of this research are related to the lack of controls in the sampling procedure, which were not implemented, due to the need to closely follow the GDPR practices of personal data protection. Since the official register of the adult education providers, compiled by AVETAE, has been used as a sampling frame, a rather rigid research procedure, following closely all of the GDPR requirements, had to be used. In future research, other sampling frames could be used (such as those compiled by the professional associations of adult education providers). This would open additional opportunities for the collection of respondents’ demographic data and additional organizational details.

The lack of public relations and sales promotion activities, which are used by approximately 10% of the responding adult education providers, also indicates the need to strengthen the marketing capabilities of adult education providers. This is not a new issue with the Croatian life-long learning providers, which were praised for their commitment to achieving high levels of peer reputation and user (student) satisfaction in a 2014 survey [43]. The continuity of the interest and knowledge gap in the field of adult education marketing has been evident at the time of developing the Strategic framework for the promotion of life-long learning in the Republic of Croatia 2017–2021 [41,42] and has not been fully addressed yet by Croatian life-long education professionals and providers. We believe correcting this issue should be a priority both for policymakers and the life-long learning professional community, as it could also contribute to the financial sustainability of life-long learning providers [43,44]. The lack of promotion and other forms of marketing communications is especially critical when it comes to programs for acquiring micro-qualifications, although public information about their co-financing through vouchers is available. As already described, this is one of the education policy priorities, both in the EU and Croatia, with ample funding available, but it is still not supported by appropriate promotional activities.

In the observed five-year period, despite significant progress, full coordination between the stakeholders of the national adult education system was not achieved. This calls for using additional opportunities provided by Croatia’s legislative and institutional educational infrastructure. While the central role of supporting policymakers and the life-long learning professional community will be retained by AVETAE, other stakeholders and institutions, mentioned by the survey participants, need to reach out to the life-long learning providers and foster co-operation with the life-long learning professional community on local and regional levels.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci13030276/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Ž., N.A. and M.V.; Methodology, T.Ž.; Formal analysis, N.A. and M.V.; Investigation, N.A.; Resources, M.V.; Data curation, N.A. and M.V.; Writing—original draft, N.A. and M.V.; Writing—review & editing, T.Ž. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the complete anonymity and voluntary participation of all survey participants.

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects involved in the study were asked for informed consent before starting the survey.

Data Availability Statement

All data are freely available in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the research and administrative support from the Croatian Agency for Vocational Education and Adult Education (AVETAE). We acknowledge valuable advice received by Jurica Pavicic (University of Zagreb, Croatia).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Loeng, S. Various ways of understanding the concept of andragogy. Cogent Educ. 2018, 5, 1496643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žiljak, T. Europeanization and policy instruments in Croatian adult education. In Adult Education and Lifelong Learning in Southeastern Europe: A Critical View of Policy and Practice; Koulaouzides, G.A., Popović, K., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Science and Education of the Republic of Croatia. New Colors of Knowledge—Education, Science, and Technology Development Strategy; Ministry of Science and Education of the Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014. Available online: https://mzo.gov.hr/UserDocsImages//dokumenti/Obrazovanje//Strategy%20for%20Education,%20Science%20and%20Tehnology.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Government of the Republic of Croatia. Nacionalna Razvojna Strategija Republike Hrvatske do 2030. Godine; Government of the Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2021. Available online: https://hrvatska2030.hr/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Nacionalna-razvojna-strategija-RH-do-2030.-godine.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Government of the Republic of Croatia. Program Vlade Republike Hrvatske 2020–2024 (Program of the Government of the Republic of Croatia 2020–2024). Available online: https://vlada.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/ZPPI/Dokumenti%20Vlada/Program%20Vlade%20Republike%20Hrvatske%20za%20mandat%202020.%20-%202024.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Ministry of Science and Education of the Republic of Croatia. Provedbeni Program Ministarstva Znanosti i Obrazovanja Za Razdoblje 2021–2024 (Implementation Program of the Ministry of Science and Education 2021–2024). Available online: https://mzo.gov.hr/UserDocsImages//dokumenti/PristupInformacijama/Provedbeni-program//Provedbeni%20program%20Ministarstva%20znanosti%20i%20obrazovanja%202021.%20-%202024.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Government of the Republic of Croatia. Nacionalni Plan Oporavka i Otpornosti 2021–2026. (National Recovery and Resilience Plan 2021–2026). Available online: https://planoporavka.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/Plan%20oporavka%20i%20otpornosti%2C%20srpanj%202021.pdf?vel=13435491 (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Council of the European Union. Resolution of the Council of the European Union on the New European Agenda for Adult Learning 2021–2030. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021G1214%2801%29 (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation of 19 December 2016 on Upskilling Pathways: New Opportunities for Adults. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOC_2016_484_R_0001 (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. CONFINTEA VII Marrakech Framework for Action: Harnessing the Transformational Power of Adult Learning and Education. Available online: https://www.uil.unesco.org/en/seventh-international-conference-adult-education (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- EUR-Lex. Open Method of Coordination. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/glossary/open-method-of-coordination.html (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Žiljak, T.; Baketa, N. Education Policy in Croatia. In Policy-Making at the European Periphery: The Case of Croatia; Petak, Z., Kotarski, K., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, N.; Fink-Hafner, D.; Lange, B. Education Policy Convergence through the Open Method of Coordination: Theoretical reflections and implementation in ‘old’and ‘new’national contexts. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 9, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkenhorst, H. Explaining change in EU education policy. J. Eur. Public Policy 2008, 15, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmola, O.P. In the Midst of the Coronavirus and Geopolitical Crises—Inventory Efficiency and Challenges Faced in Finland. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žiljak, T. Ciljevi europskih politika obrazovanja odraslih u vrijeme pandemije COVID-19. Adult Educ. J. Adult Educ. Cult. 2022, 2, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Adult Education and Training in Europe: Building Inclusive Pathways to Skills and Qualifications; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Adult Learning and COVID-19: How Much Informal and Non-Formal Learning Are Workers Missing? Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1069_1069729-q3oh9e4dsm&title=Adult-Learning-and-COVID-19-How-much-informal-and-non-formal-learning-are-workers-missing (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Commission. The European Pillar of Social Rights in 20 Principles. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/economy-works-people/jobs-growth-and-investment/european-pillar-social-rights/european-pillar-social-rights-20-principles_en (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Commission. European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=22832&langId=en (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Commission. The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/aedac865-8dbd-4841-bb05-90dd22418943_en (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Commission. Commission Proposal with Council Recommendations on Individual Learning Accounts. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0773 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A New Skills Agenda for Europe—Working Together to Strengthen Human Capital, Employability and Competitiveness. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/HR/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52016DC0381&from=EN (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Pastuović, N.; Žiljak, T. (Eds.) Obrazovanje Odraslih: Teorijske Osnove i Praksa; Faculty of Teacher Education and Open University Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, M.B. The Forgotten 90%: Adult nonparticipation in education. Adult Educ. Q. 2018, 68, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degerman, D.; Flinders, M.; Johnson, M.T. In defence of fear: COVID-19, crises and democracy. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Political Philos. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjursell, C. The COVID-19 pandemic as disjuncture: Lifelong learning in a context of fear. Int. Rev. Educ. 2020, 66, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žiljak, T.; Matković, T. Obrazovanje odraslih. In Obrazovne Nejednakosti u Hrvatskoj: Izazovi i Potrebe iz Perspektive Dionika Sustava Obrazovanja; Farnell, T., Ed.; Institut za Razvoj Obrazovanja: Zagreb, Croatia, 2022; pp. 60–74. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, R.; Hodge, S.; Holford, J.; Milana, M.; Webb, S. Life-long education, social inequality and the COVID-19 health pandemic. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2020, 39, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milana, M.; Hodge, S.; Holford, J.; Waller, R.; Webb, S. A year of COVID-19 pandemic: Exposing the fragility of education and digital in/equalities. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2021, 40, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N.; Thériault, V. Adult education in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Inequalities, changes, and resilience. Stud. Educ. Adults 2020, 52, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtinen, H. Future of Adult Education. Available online: https://elmmagazine.eu/future-of-adult-education/tomorrows-learning-utopias-and-dystopias/ (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. Fourth Global Report on Adult Learning and Education: Leave No One Behind—Participation, Equity and Inclusion; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning: Hamburg, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000372274 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Gouthro, P.A.; Holloway, S.M. Using a multiliteracies approach in adult education to foster critical and creative pedagogies for adult learners. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 2020, 26, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyadjieva, P.; Ilieva-Trichkova, P. Adult Learning as Empowerment: Re-Imagining Life-Long Learning through the Capability Approach, Recognition Theory and Common Goods Perspective; Palgrave MacMillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Decuypere, M.; Vanden Broeck, P. Time and educational (re-)forms—Inquiring the temporal dimension of education. Educ. Philos. Theory 2020, 52, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüter, F.; Martin, A. How Do the Timing and Duration of Courses Affect Participation in Adult Learning and Education? A Panel Analysis. Adult Educ. Q. 2022, 72, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žiljak, T.; Lapat, G.; Rajić, V.; Pavić, D.; Černja, I. Kurikulum za Razvoj Temeljnih Digitalnih, Matematičkih i Čitalačkih Vještina Odraslih: Temeljne Vještine Funkcionalne Pismenosti; Ministry of Science and Education: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019. Available online: https://mzo.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/Obrazovanje/ObrazovanjeOdraslih/Publikacije/kurikulum_temeljne_vjestine_funkcionalne_pismenosti.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Matković, T.; Jaklin, K. Podaci o obrazovanju odraslih. Andrag. Glas. 2022. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Vučić, M.; Piljek Žiljak, O.; Vučić, N. Obrazovanje Odraslih u Hrvatskoj 2017—Rezultati Istraživanja; Agency for Vocational Education and Adult Education: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Žiljak, T.; Alfirević, N.; Pavičić, J.; Vučić, M. The promotion of vocational and adult learning in Croatia: Results of a policy initiative and generic implications for policy and education practice in South-East Europe. Andrag. Stud. 2018, 1, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AVETAE. Strategic Framework for Promotion of Lifelong Learning in the Republic of Croatia 2017–2021; Agency for Vocational Education and Training and Adult Education: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017; Available online: https://epale.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/strateski_okvir_engl_priprema.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Mihanović, Z.; Pavičić, J.; Alfirević, N. Analysis of organisational performance of non-profit institutions: The case of life-long learning institutions in Croatia. Econ. Rev. J. Econ. Bus. 2014, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Najev Čačija, L. The nonprofit marketing process and fundraising performance of humanitarian organizations: Empirical analysis. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2016, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).