Abstract

In the current higher education context, higher education institutions need, more than ever before, to compete for students, attracting, retaining and, ultimately, graduating them. To this end, actions are increasingly developed, and conditions are created to promote student success. The literature demonstrates that there is a strong link between the students’ experience and success. However, students’ experience cannot be controlled by the higher education institution, given the existence of previous subjective experiences that students bring when they enroll in higher education, which act as filters of their current experiences. The central goal of this study is to unveil the factors that students perceive as influencers on their global experience in higher education, which are reflected in their path, performance and success. The methodology used is qualitative, with in-depth interviews with students and institutional leaders from four Portuguese higher education institutions, complemented with documentary analysis. The results reveal that individual and organizational factors, alongside the students’ global experience, clearly influence their definition of a successful higher education student. Students build their representations of success based on the multiplicity and complexity of their experiences in higher education, affected by the features of the higher education institution and mediated by their personal history and life project.

1. Introduction

In the contemporary context of significant reconfigurations experienced in the arena of higher education (HE) worldwide in recent decades (namely its massification, the growing scarcity of resources and institutional competition for students), the way higher education institutions (HEIs) relate to their audience has been shifting. The academic community, governmental structures and the HEIs themselves have been focusing on topics related to how students seek HE and, once in the system, how they adapt, perform, get involved and attain success. In this context, one of the HEIs’ dominant concerns is how to retain students, thus preventing them from dropping out.

Diverse authors maintain that students’ perceptions of their global experience in HE play a pivotal role in their performance and consequent success, as well as in their degree of commitment to the institution they are enrolled in [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. This perception and how students experience their path have psychological, sociological, cultural, economic and other influences, some of which cannot be controlled by the HEI. However, there are ways that institutions can influence the students’ experience, and this influence can be either positive or negative [9].

In the context of this research, global experience means the whole set of students’ experiences as members of the academy. This global experience is subdivided into academic experience, social experience and functional experience. Although the literature argues that students’ experience stems from a wide range of factors, it sometimes presents it by focusing more on one or another type of experience. The results of this study allow concluding that global experience interrelates the totality of HE students’ experiences.

This study had, therefore, the central purpose of unveiling the factors that students perceive to influence their global experience in HE, which are reflected in their path, performance and academic success. Thus, the aim is to attain a more in-depth knowledge of students’ perceptions of their success in HE as a result of their experience in the HEI.

To do so, an in-depth analysis was carried out of four Portuguese public HEIs located in the North of Portugal. The methodology chosen is qualitative, using the multiple case study methodology, and the techniques employed were (1) semi-structured interviews with students; (2) semi-structured interviews with institutional leaders; and (3) document analysis. The research technique elected for the treatment of the data collected was content analysis.

The knowledge gathered on students’ perceptions of their success in HE as a result of their overall experience in the HEI, which combines the established literature on the field and the results of this study, and specifically the model created, may become a useful tool for HEIs’ policy makers when designing strategies aiming to keep their students motivated and satisfied with their overall experience in the institution and, therefore, more likely to persist and attain success.

2. Theoretical Underpinnings

The study of the factors that influence the performance, satisfaction and success of HE students is well documented, having been the focus of attention of academics and HEIs in recent decades [1,5,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Most of these studies have produced models of analysis of students’ academic experience, which seek to understand and explain their behaviors during their path at this educational level.

Although all the models analyze the factors influencing students’ performance, they can be grouped according to their theoretical focus [19]. Models can have (1) a sociological focus, emphasizing the traits students bring when they enroll in HE and their interaction with the features of the institution they enroll in. The balance of this relationship is ensured by the students’ positive academic performance and by their decision to remain in the institution and in the study program [1,20]; (2) an organizational or institutional focus, highlighting the HEIs’ institutional structures and processes of the HEI that may affect students’ success [16,21,22]; (3) a psychological focus, according to which students’ personality traits influence their attitude towards the challenges posed by HE [12,23]; (4) a cultural focus, which highlights the increased challenges that historically underrepresented students have to face in their academic trajectory [24,25,26]; and (5) an economic focus, which postulates that students establish a balance of the costs and benefits of attending HE and their involvement in the activities offered by the HEI [27,28].

Although research on individual factors is a relevant contribution to understanding this problem, multifactorial models have the advantage of allowing the analysis not only of the association of each individual feature or construct with academic performance and success but also of the relationships established between these features. These models are, therefore, necessary, inasmuch that a single indicator cannot, by itself, explain a phenomenon with the complexity that characterizes education. In other words, none of the models and theoretical concepts found in the literature is, per se, capable of circumscribing all the factors that affect HE student performance. However, these perspectives, taken together, provide a holistic view of the myriad dimensions that contribute to the students’ academic experience resulting in the success or failure of their path.

Global HE students’ experience can be broken down into three main types. The academic experience is one of the components of the global experience [1,5,19,23,29,30] and plays a pivotal role in students’ persistence and success [31]. This concept is related to the attainment of educational goals, intellectual/cognitive development, and learning. It also includes the relationship/interaction with teachers and peers within the classroom, the perception of the relevance of the subjects and their content, time management, the quantity of time and energy devoted to studies and student satisfaction with their study cycle.

The social experience focuses on interaction and the establishment of relationships between all members of the academic community outside the classroom, that is, in a more informal environment. This experience also includes the type and degree of involvement in co-curricular activities offered by the HEI and the students’ process of integration/adaptation to the institutional environment. According to Astin’s [32] Theory of Student Involvement, student academic and social involvement plays a major role in shaping their academic results, which later studies [12,33,34,35] corroborate. The literature acknowledges and emphasizes the relevance of the students’ social experience in their integration in the institution and the subsequent commitment to it [5,7,8,22,23,36].

The literature defines functional experience as the set of aspects deemed necessary for the student to be a participating member of the academic community but which are not directly related to academic and social aspects [37,38]. This includes the bureaucratic elements of the HE experience and the spatial orientation on campus.

In the student global experience, two types of factors have a significant influence: individual and organizational factors. The literature identifies individual factors as likely to exert an important influence on students’ global experience throughout their path in HE [5,37,39]. This set of traits influences both students’ academic performance and their commitment to their individual goals and the institution. The second set regards the organizational/institutional factors. The internal organizational structures, practices and policies can exert, according to the literature, a significant influence on the students’ results through the type of experiences and values they convey [40,41,42]. The context in which the academic experience takes place can have a considerable impact on student involvement and performance and on their decision to remain/drop out from the HEI. The conclusions of the study by Vossensteyn et al. [43] on dropout and completion in higher education in the European context corroborate previous research on the factors affecting student performance and success, especially in terms of the individual and institutional dimensions. In particular, the authors underline the relevance of, on the one hand, individual factors, such as “[…] the knowledge and expectations of the individual student about the study program, the socio-economic background of students as well as the amount of paid work students do alongside studying institutional factors” [43] (p. 89). On the other hand, the context of the HEI and the conditions provided to students have a pivotal role in students’ performance and success, pointing out the main influences, namely, “[…] the matching of students and study programs; teaching and learning initiatives to develop more student-centered and active learning approaches; systematic tracking and monitoring of students’ success; and the organizational context surrounding study programs” [43] (p. 89).

Based on the literature review put forth and the main purpose of this paper, the following research question was defined:

RQ1: Which factors do HE students perceive as influencers on their global experience in HE, which are reflected in their path, performance and academic success?

3. Methodology

The methodology chosen is qualitative, given that the author seeks to analyze the interpretations of the subjects involved in a given social phenomenon, which is believed to be paramount for its understanding [44]. Thus, the multiple case study methodology was chosen. An in-depth analysis was carried out of four Portuguese public HEIs: two universities and two polytechnic institutes from the public sub-sector. The choice of the multiple case study methodology [45], by analyzing four higher education institutions, enabled, on the one hand, obtaining an understanding of the phenomenon under analysis within each of the institutions and, on the other hand, the other made it possible to compare institutional types, represented in each of the subsystems of Portuguese higher education, taking into account the size of each institution.

3.1. Sample

For the selection of participants from the four HEIs that make up the case study, the following criteria were considered: the nature of the study program (1st and 2nd cycle, or degree and master’s degree); the nature of knowledge (hard-pure, soft-pure, hard-applied e soft-applied [46]); and gender. Institutional leaders were also included in the sample. These leaders are individuals with some degree of involvement in institutional decision-making, such as Vice-rectors/Pro-rectors and Vice-presidents; the Student Ombudsman; student representatives on the Pedagogical Council; and Presidents of Student Unions. This way, it was sought to include key institutional actors/groups of actors to get a comprehensive set of perceptions on the topic under analysis from the different actors. Thus, the sample is composed of 58 institutional actors, detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of the study sample.

A sample reflective of the usual distribution of gender was also sought. However, considering the small size of the sample—given its qualitative nature—the number of male and female HEI students turned out to be equivalent. Thus, it was decided to use the parity criterion, i.e., female and male students were considered in equal numbers in the design of the sample.

A total of 60% of the students surveyed are displaced, i.e., do not live with their nuclear family during their academic path. There is a high dominance of full-time students (72.5%). Regarding the nature of knowledge, there is a prevalence of students enrolled in study programs from the Soft Applied area (37.5%), followed by the Soft Pure area (27.5%). Third are the students enrolled in study programs from the Soft Applied area (22.5%) and, finally, students in the Hard Pure area (12.5%).

The household income of the students surveyed is between the minimum value of EUR 500.00 and the maximum value of EUR 6000.00. The sample consists mainly of students whose household income is between EUR 1000 and EUR 3000.00 (60%), belonging to the middle class in socioeconomic terms.

In terms of the distribution of the sample by age range, more than half of the students in the sample (60%) are between 21 and 25 years old, 22% of the students are between 18 and 20 years old, 10% of students are between 31 and 35 years old, and 8% are between 26 and 30 years old.

Regarding the students’ sociocultural status, specifically concerning the parents’ education, the highest percentage of both fathers and mothers is concentrated in non-higher academic educational levels (1st, 2nd, and 3rd cycles and secondary education), accounting for 65% of the cases in the study sample. In only 10% of cases, both parents of the students interviewed have tertiary qualifications.

3.2. Data Collection

Data collection followed three complementary paths: (1) a semi-structured interview with students; (2) a semi-structured interview with institutional leaders; and (3) document analysis. The combination of these three techniques, by enabling data triangulation [47], allows establishing a platform of greater confidence, credibility and validity of the results attained [48,49,50].

Underlying the choice for the semi-structured interview is the assumption that it is a privileged way of collecting data on individuals’ personal histories, perceptions, feelings, perspectives and social worlds [51,52].

The interviews took place in locations convenient for the interviewees, indicated by them, always on the premises of their institutions.

The interview began with informing the interviewees about the purposes of this study. Then, complying with ethical research principles, respondents were ensured data anonymity and confidentiality [53]. This is a fundamental procedure in carrying out in-depth interviews, inasmuch that during the interviews, respondents may disclose and share information that may call into question their position in a given system. This information must, therefore, be anonymous to guarantee its protection.

The interviews were audio-recorded after authorization from the interviewees and transcribed in full for subsequent analysis.

Concurrently with data collection through semi-structured interviews, the document analysis method was also used in this study, which consists of “[…] a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents—both printed and electronic” [54] (p. 27). Documents made available by the institution were analyzed, namely its strategic plan, activity reports and other documents, as well as the institution’s website on the Internet.

3.3. Data Analysis

The research technique used in the treatment of the data collected was content analysis. This technique, according to Krippendorff’s [55] definition, allows the compression of a high amount of words and text in a smaller number of content categories, based on explicit coding rules.

Content analysis then incorporates, according to what Bardin [56] advocates in a work deemed classic due to its relevance, a set of communication analysis techniques that uses systematic and objective procedures for describing the content of messages conveyed through the various communication channels. Thus, when used correctly, content analysis is a powerful technique that allows researchers to filter large volumes of data relatively easily and systematically [57].

Regarding the data coding strategy followed, the phrase or set of phrases of a text segment or, in some cases, a paragraph, were considered a text unit to code. Following Saldaña [58], the process of data coding started when the first interviews and institutional documents were analyzed, in the pre-coding phase; the codes were, in a second phase (or first cycle of codification), refined and organized into categories and subcategories through a deeper analysis of the data and, finally (in the second cycle of codification), compared among themselves and consolidated, in the sense of progression towards the formation of themes, which, in turn, lead to the emergence of theoretical constructs. In this study, a set of categories coded a priori was built. However, the categorization initially created was not a closed system; the analysis of the data enabled the establishment of emerging categories, that is, categories that were incorporated into the categorical system as the data analysis progressed.

Section 4 puts forth and discusses the results attained in this study. Excerpts from the students’ and institutional leaders’ narratives are provided in this section to illustrate the results.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Academic Experience

The personal/individual component of the academic experience analyzed the subjective assessment that students make of achieving their goals of integral development, their satisfaction with the study cycle, and their study patterns.

The number of students who claim to be satisfied with their expectations of attaining the initially set educational objectives is quite high. A student from a university states that the study program she is enrolled in “[is] what I expected, I have nothing to point out […] it has always lived up to my expectations, and I am extremely happy to have enrolled in this HEI”. In some cases, there is an expectation that these objectives have been clearly exceeded. Thus, overall, satisfaction with academic experience is positive, although some students comment that their initial objectives will only be partially fulfilled. As a master’s student from a polytechnic institute claims, “I cannot say I do not like it; it is just not what I was expecting”.

Regarding satisfaction with the study cycle, students are generally satisfied with this dimension of their academic experience. This satisfaction is associated with the program content, faculty, teaching methods, the perception that academic training is contributing to their personal development and, in general, a high correspondence vis-a-vis the initial expectations. Some students, although globally satisfied, state that, if they could, they would change some of the structural and curricular components of their programs, insisting more on the “know-how”, their connection to the business world and more active forms of assessment. In this regard, a master’s student from a university comments that, notwithstanding being satisfied, he “[…] would change some aspects, obviously, nothing is perfect. Maybe it [study program] lacks some connection to the industry, to the market itself, it is more academic”. Another group of students, however, reveals dissatisfaction with their program, although it is a moderate dissatisfaction, associated, above all, with the curricular contents, some of the adopted methodologies and a sometimes poor balance between the theoretical and practical components of the program. A master’s student from a university states: “I am a little disappointed with the master’s, honestly, because I thought it would be a continuation of the bachelor’s, and what I found was not quite that; it was almost a return to the 1st grade of the bachelor’s”.

The study patterns described by the participants enabled identifying different groups of behaviors. A group of students emerges to whom studies are at the top of their priorities and to which they channel a considerable share of their time and energy. However, the most common behavior is that there is an unequal commitment throughout the academic year, during the study cycle and regarding the various subjects of their study program. As a master’s student from a polytechnic institute states, “Honestly, I spend more energy when there are assignments or tests […]. I prefer to focus the energies when the time comes, to give my best at that time”. In general, all students agree that an important investment is necessary for adequate management of the time and energy devoted to studying and achieving the objectives they have set for themselves.

The academic interpersonal component materializes in the relationships/interactions established with peers and teachers in the classroom. The analysis of the narratives reveals that peer relationships are characterized, in general, by sharing and helping each other in academic terms in an environment perceived as healthy. As a master’s student from a polytechnic institute mentions, “In terms of the relationship with colleagues, I think it is very good, I think we have an open, healthy relationship, there is no competitiveness, there is a spirit of mutual help, we share things”. The existence of subgroups within the large class group is also identified, as well as emerging representations of peer relationships characterized by reduced proximity.

Regarding the relationship/interaction between students and teachers, in general, students state that this relationship, established in the classroom, is characterized by availability, cordiality, proximity and informality. As a bachelor’s student from a university comments, “I feel that whatever difficulty we are going through, they [teachers] help us, they are always available to help us […] there is proximity”. Contrarily, another group of students represents teacher-student relationships as distant, formal and impersonal. A master’s student from a university claims that “there are cases in which I think that the relationship is somewhat difficult, especially with more senior, more experienced teachers”.

Overall, the results of this research reveal that students acknowledge the relevance of extracurricular activities, as a complement to their scientific training, in a more comprehensive and global training logic. This positioning confirms the importance, described in previous studies [59,60], of the involvement of students in educational activities beyond the classroom. Students get involved and participate in numerous events, from cultural to playful and/or sporting and associative events. However, academic events are the ones in which students seem to participate the most, considering that they are a direct added-value for their specialized training. As a master’s student from a university comments, “I tend to participate more when they [extracurricular activities] are linked to my area. [...] I normally attend lectures and conferences”. Comparing students’ perceptions with those of institutional leaders, it is possible to find a gap between what students say and what leaders perceive. The latter see students’ involvement in actions outside the scope of the curriculum as being reduced to the participation in co-academic events, such as workshops, lectures, seminars and conferences, despite the institutional effort to offer opportunities for student involvement in the academic, cultural, social and recreational life of the HEI, with a leader from a university stating that “[…] there is a difficulty in mobilizing students for this type of activities”.

4.2. The Social Experience

Social relationships, which are established beyond the boundaries of the classroom, do not entirely follow the same line as peer relationships inside it (perceived as very positive and guided by mutual help, companionship and sharing). While some students characterize these relationships as taking place beyond the limits of the HEI, others circumscribe them to the academic environment. Peer interactions are restricted to a relationship of colleagues, who help each other throughout their studies, but from which affections are excluded. As a master’s student from a university comments, “I do not meet them [peers] outside the university, let us say they are my colleagues […] in my case, the relationships are more in terms of the classroom and the campus”.

In turn, the relationships established between teachers and students are perceived, in general, as positive by the participating students. However, these relationships, albeit cordial, are limited, in some cases, to the formal academic context of the classroom. A bachelor’s student from a university argues that “[The relationship] is very impersonal [...] I do not think there is a proximity between students and teachers”. Yet, some interviewed students represent the relationships with their teachers as being able to take place outside the classroom, in a more informal environment.

4.3. The Functional Experience

Students perceive bureaucratic processes and procedures as hindering their functional experience. There is a perception that this unavoidable dimension of student support should be re-balanced. In any case, very few students stand up against the bureaucratic burden in their institutions.

Regarding the students’ spatial orientation on campus, there are, on the one hand, students who quickly overcame some initial difficulties through the help of peers and staff. The strangeness of their new “home” did not last more than a few days or, in some cases, a few hours. On the other hand, some students internalized a feeling of bewilderment, as they felt completely lost, which marked their first impressions regarding the HEI.

Most students perceive the environment in their institution as positive, welcoming and enhancing the establishment of relationships and the sharing of experiences. The physical dimension of the institution plays a major role in the students’ perception of the institutional environment. This variable influences students’ perceptions, as those who attend small HEIs perceive the environment as welcoming, pleasant and almost familiar, contrasting those who attend large HEIs, who tend to envisage a more distant environment among the institutional actors.

According to the perceptions of some students, human relationships are identified as the most positive aspect in terms of the institutional environment. Healthy relationships between all the actors of the academic community are, for most students, the factor that contributes, to a greater extent, to the positive institutional environment of their institution. In summary, although some students mention that, as a social system composed, therefore, of people, and, hence, liable to some flaws in terms of human relationships, in general, students are quite satisfied with the institutional environment.

4.4. Individual Factors

Students have a set of individual traits that, according to the literature, exert influence on their academic career in HE. This study addressed the expectations of students when enrolling in HE; the involvement and academic path prior to HE; the rationalities of choice; and integration and adaptation to HE and the HEI.

Regarding students’ expectations, their attention seems to be focused on obtaining a diploma, promoting their personal and integral development and attaining labor market-oriented competencies. For most students, attending HE is part of a “normal” path of broad training and education, shaped by expectations and the cultural, social and informational capital accrued by families. As a bachelor’s student from a university comments, “I think it was the natural thing to do. […] it was already intrinsic in the family and even school context, […] it was almost like a natural path”.

The students report that they had knowledge of the information that served as the basis for their choice of the HEI and the study program in three different sources: information provided by the HEI, information conveyed by significant others and knowledge through the presence in events promoted by the HEIs.

Regarding student integration/adaptation to the HEI, the respondents comment that their first experiences were quite challenging, as they involved socializing in a new and different environment, completely from the one they were used to. However, students also state that they overcame these initial obstacles easily and quickly. A bachelor’s student from a polytechnic institute asserts that “the first days are always difficult; it is a new institution, new faces, we do not know anyone, but we adapt, get to know them”. Yet, for other students, there is a feeling that they were “lost”, “bewildered” in the immensity of a university campus, compared to the high school small size. As a bachelor’s student from a university comments, “[…] it was a bit of a shock because it was very different from high school. Here the teachers explain well, but we have to start broadening our horizons”.

4.5. Organizational Factors

Regarding the HEIs’ internal structures, policies and practices, the type of education pursued by each institution (universities and polytechnic institutes) is reflected, as would be expected, in their mission. Universities offer a more scientific and cultural-based training offer, whereas polytechnics define, as their mission, social transformation and economic development in the region where they are inserted, providing a more professionalizing training offer.

The institutional discourse about students, their role and place in the HEI and the teaching-learning process is characterized by high homogenization, insofar that all HEIs place the student at the center of the educational process as a fundamental and legitimizing mainstay of their action. The institutional leader of a university claims that “[the students] are the center of everything […] and they are always one of the fundamental pillars, it has and will always be like this, they are the primary reason”. Similarly, the stance of the institutional leader of a polytechnic institute is that of “envisaging students as people and as the absolute center of our mission”.

The students’ assessment of the quality of the HEI’s physical structure—facilities and equipment—is globally positive. They perceive HEIs as being adequately equipped, in general terms, with the necessary conditions for the development of academic activities and extra-academic activities of a more playful nature. A bachelor’s student from a university states that “[…] the university is well equipped, from what I know of other schools, I think this one is very well equipped. For me, the conditions for classes are great”, and a master’s student from a polytechnic institute adds that “overall, I think we have very good conditions, not only in terms of facilities but also in terms of equipment”.

Regarding curricular and co-curricular programs, policies and practices, HEIs take on as their main concern the need to adapt their training offer to the existing needs in the labor market, as well as to provide training that meets the employment opportunities in that same market. The leader from a polytechnic institute comments that “Our strategic plan contemplates a very well defined goal, which is to adapt our training offer to the market needs”. Along with this concern to adapt the offer to demand, the HEIs admit that the attempt to adapt the training offer to the human competencies existing in the institution also underlies the design of their study plans, in a more instrumental positioning of the educational offer preparation process. A university leader states that “we must offer the best we have, we have installed competences, we have research, we must make it available to the public”.

In terms of differences between the intended curriculum, that is, the one that the HEIs intend to convey in training, and the promulgated curriculum, that is, the curriculum actually put into practice, the HEIs are aware that these discrepancies exist. This is due, on the one hand, to the poor adequacy between contents and methodologies and the attainment, by the students, of the so-called transversal competences and, on the other hand, to their audience, that is, the students, their expectations, aspirations and difficulties, which may not match what they receive from the HEI. According to a university leader, “although there are no significant differences, there are always differences depending on the reality of the students we have”. HEIs advocate dynamic learning and teaching processes, constantly changing, continually evolving, and in which the various actors should, ideally, be active participants. These results corroborate those of previous studies, namely that of Leite and Ramos [61], who concluded that there is a tension between what is proposed and what is effectively put into practice.

5. Conclusions

The results put forth and discussed allow affirming that the HE students’ global experience is a multidimensional process, composed of a vast set of experiences, which encompass (1) the academic experience (which directly concerns the learning and teaching process within the classroom); (2) the social experience (which relates to interaction and the establishment of relationships with peers and faculty outside the classroom); and (3) the functional experience (which includes everything necessary for the student to become a participating and active member of the academic community, but that is not directly related to academic and social aspects).

This wide set of experiences is clearly modelled by students’ perceptions regarding the HEIs’ features, practices and organizational conditions, namely in terms of their internal structures, policies and practices; the vision they convey of the student and their role in the educational process; the institutional communication processes and student participation in institutional decision-making; the monitoring that HEIs make of their students’ path; support during and after training; the quality of the HEIs’ physical structure; curricular and extracurricular programs, policies and practices promoted by HEIs; and, finally, the provision of opportunities for students to become actively involved in the life of the academy.

However, organizational factors are not the only influences students have throughout their academic training. Individual factors also play a highly relevant role, i.e., the traits, personal processes and previous experiences that students bring when they enroll in HE. These factors act as a filter in their interaction with the HEI and the opportunities it offers them, both in terms of scientific training and, more globally, in a logic of overall training.

All of these factors, alongside the students’ global experience, have evident repercussions on their definition of a successful HE student. Students build their representations of success based on the multiplicity and complexity of their experiences in HE, conditioned by the features of the HEI and mediated by their personal history and life project [62].

The several conceptual models that have been developed in the field focus more on one or another theoretical perspective, emphasizing, as such, certain traits of the students, their experience in HE and the context in which that experience takes place. With the model analysis offered in this piece of research, we seek to attain a broader understanding of the factors that influence student performance and success.

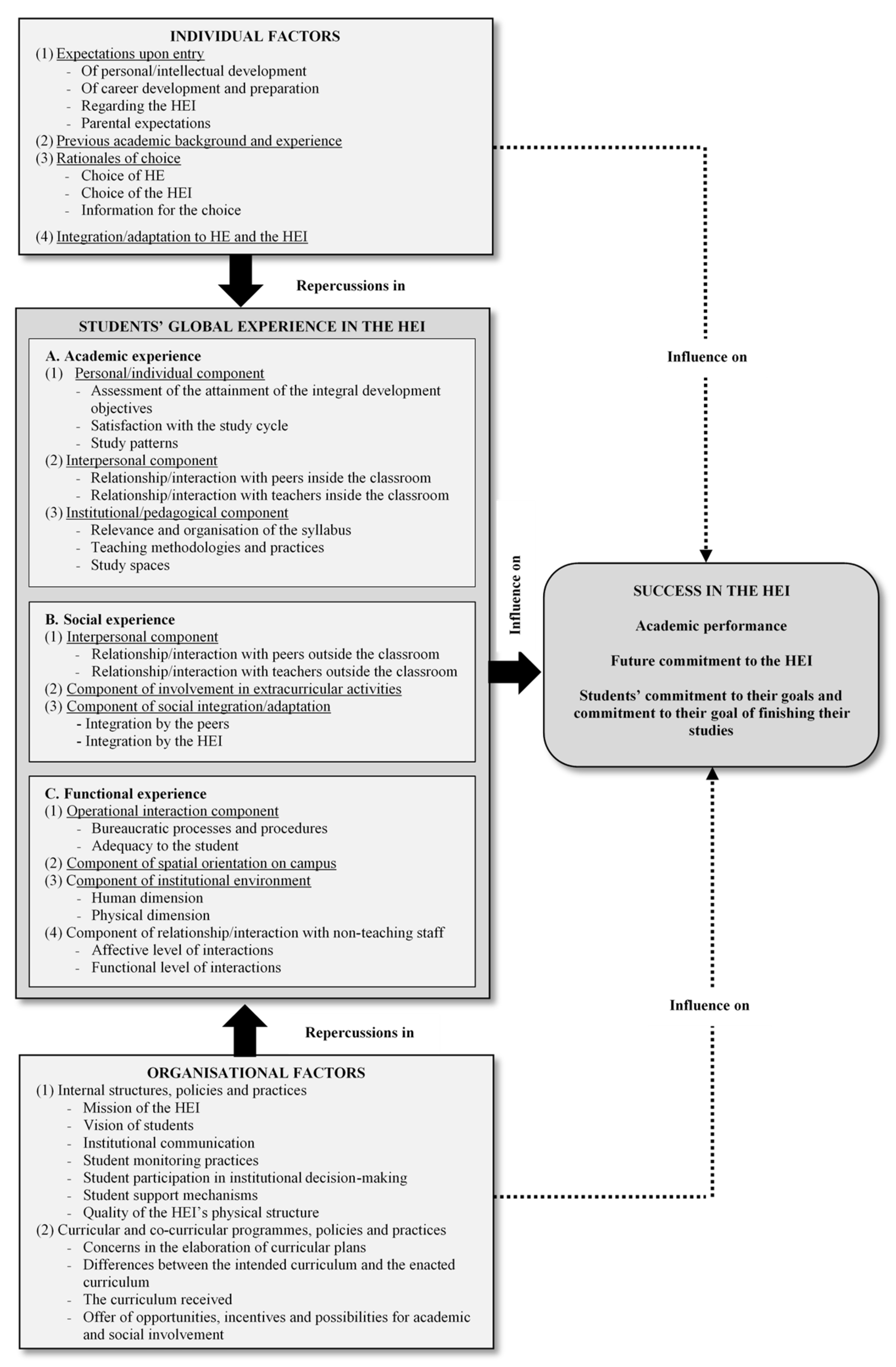

This study analyzed a comprehensive set of variables, which emerged from both the literature review and the empirical data, detailed in Figure 1, that make up students’ global experience, which encompasses academic, social and the functional experiences. In turn, this overall experience is influenced by individual and organizational factors. The results of the study demonstrate that these conditions cannot be disconnected, as both play a profoundly relevant role in students’ global experience.

Figure 1.

Multidimensional model of the student experience. Source: Author’s production.

Based on the results of this research, as well as on the several approaches on higher education student performance, satisfaction and success produced in recent decades, a multidimensional model of analysis of student experience was developed (Figure 1).

According to the model developed, students’ experience is a multidimensional construct composed of their experience in academic and more formal terms, in social and more informal terms, and in their functional interaction with the HEI. This experience is conditioned and influenced by students’ individual traits, articulated with the organizational context in which it takes place. The students’ global experience develops in the balance between these diverse forces, and the result of this balance will shape their academic performance, their commitment to their goals and, ultimately, their present and future commitment to the HEI, which corroborates the conclusions of previous studies [4,26,63]. The model developed in this work seeks, therefore, to offer an integrated and, consequently, a holistic perspective of students’ experience and its drivers, as well as how it affects their academic performance. The plethora of factors described above as influencers of the students’ global experience in HE provide the answer to the research question set out in this article (RQ1: Which factors do HE students perceive as influencers on their global experience in HE, which are reflected in their path, performance and academic success?).

In view of these results and the knowledge of what students perceive as most important in their experience, HEIs will be in a position, when preparing their strategic plans, to include their students’ vision. For this, intentional and systematic listening of students is highly relevant, actively involving them in institutional decision-making and trying to understand what it means for them to attain success in HE. By being aware of what, for students, is a successful student, HEIs will have important elements to try to model their policies and practices to converge their offer to the expectations and needs of their audience.

Students have, in their own words, to feel “at home”, to find a “second family” there, to feel the desire to go daily to their HEI, to enjoy being on campus, to engage in extracurricular activities, to feel cherished and protected by the HEI, to feel that their opinion counts, to establish lasting ties with the other institutional actors, to find meaning in the curricular contents. In short, students wish to be happy in the institution, and it has a pivotal role in promoting this well-being and happiness in its students, as also revealed in previous studies [63,64,65,66]. This is, perhaps, one of the paths to their success, and this is what HEIs must focus on so that the academic community that they are responsible for, and in particular their students, feel that the time they spend at the HEI and what they build there is shaping their experience and preparing them for the future.

In terms of the contributions of this study to theory, the various conceptual models developed in the field focus more on one or another of the several theoretical perspectives, emphasizing, as such, certain student features, their experience in HE and the context in which this experience takes place. The model of analysis proposed seeks to be an instrument that allows HEIs to attain a broader understanding of the factors influencing student performance and success. A comprehensive set of variables that make up the students’ overall experience was analyzed. This experience is, in turn, influenced by individual and organizational/institutional constraints. The results of the study demonstrate that these constraints cannot be dissociated as both play a highly relevant role in the students’ global experience. This is the main merit of the model developed, inasmuch that it offers an integrated, comprehensive and holistic perspective of students’ experience and its drivers, as well as how it affects their academic performance, satisfaction and, ultimately, success.

According to the model developed, the students’ experience is a multidimensional construct, composed of their experience in academic and more formal terms, in social and more informal terms, and their functional interaction with the HEI. This experience is affected and has several influences from the students’ individual traits, articulated with the organizational context in which it occurs. The students’ overall experience develops in the balance between these various forces, and their academic performance, the commitment established with their own goals and, ultimately, their present and future commitment to the HEI is a result of this balance. The model developed thus seeks to offer an integrated and, consequently, holistic perspective of the student’s experience and their constraints, as well as how this affects their academic performance.

The conclusions of this study reveal the scope and complexity of the teaching and learning process that happens in HE [34]. This process does not occur in a void and is influenced by a wide range of factors. Students have long ceased to be seen as sheer repositories of information and knowledge. Today, it is known that it is paramount to consider the individuality of each student and seek to adapt this process to their expectations and needs.

While the institutional discourse about students and their place and role in the teaching and learning process is characterized by a high convergence, students do not always feel they have a central role in this process. Thus, it is up to HEIs, in addition to the traditional and usual academic surveys, to search for other ways to listen to students, to clearly understand their expectations regarding their training and life at the HEI [67].

The instrument herein offered for approaching students’ reality seeks to be a tool for analyzing and assessing the reality of HEIs, so they may have enhanced knowledge and, thus, understand their students’ aspirations, goals, needs and complaints. This may be a path for institutional policy makers to be in better conditions to define improved strategies for their students’ integration and development.

This study does not go without limitations. The first stems from the chosen methodological approach. When choosing a qualitative methodology, it is not possible to make generalizations, given that the purpose of qualitative research is not to generalize the results but to describe, interpret and ascribe meaning to the subjects’ position regarding a given situation. The results of qualitative studies cannot be tested to verify whether they are statistically significant or due to chance [68]. Thus, the results of this study do not allow for generalizations but rather provide a framework that has the potential to be implemented in a different (geographical, economic or cultural) context.

The second limitation concerns the number of cases studied and their geographical location. This work was limited to four case studies in the North of Portugal. Despite the fact that the choice of HEIs to be studied sought to obey some criteria that could allow these cases, in some way, to reflect the Portuguese reality, it is not possible to extrapolate the results of this study to the universe of Portuguese HEIs. In any case, given that the model has been built based both on national and international literature on the topic of higher education student experience and on the empirical findings of the study, it has the potential to be transferred to the rest of Portuguese higher education and, possibly, to HEIs in other countries, provided that adaptations are made according to the specific universe to be studied.

Another limitation of this study is related to the dimensions of analysis selected to study the reality in question. When selecting individual and organizational constraints as the focus of influences on the students’ global experience, others identified by the literature as equally relevant, namely cultural and economic constraints, were excluded. While cultural constraints do not seem central to the reality of Portuguese HE, economic constraints, considering the recession that the country is going through, could add to the increase in the wealth of the results attained and to the deepening of the topic under discussion.

In terms of avenues for future research work, concerning the research methodology used, namely the methods and instruments for empirical data collection, future studies may complement it with in-depth interviews with key informants and document analysis with the use of a questionnaire survey, which would allow, on the one hand, the use of a larger sample and, on the other hand, the quantification of at least some of the results. Additionally, a second recommendation is the development of a scale to assess the relative weight of each study variable in the student overall experience and the relationships between them. Regarding the delimitation of the study in geographical terms, it may be interesting to replicate this study in other areas of the country, which would allow the development of comparative studies in regional terms, namely north/south, coast/inland and mainland Portugal/islands. Moreover, this model has the potential to be replicated in international higher education scenarios.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., within the scope of the project UIDB/00757/2020 of CIPES—Centre for Research in Higher Education Policies, by national funds through FCT/MEC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of CIPES (protocol code 04/2022 and date of approval is 10 November 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Astin, A. Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1999, 40, 518–529. [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanu, A. The role of student services in the improving of student experience in higher education. Procedia–Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 92, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemenčič, M.; Chirikov, I. How do we know how students experience higher education? On the use of student surveys. In The European Higher Education Area; Curaj, A., Matei, L., Pricopie, R., Salmi, J., Scott, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, I. The Student Experience of Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pascarella, E.T.; Terenzini, P.T. How College Affects Students. Vol. 2. A Third Decade of Research; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sakr, M. Deleuzian approaches to researching student experience in higher education. In Theory and Method in Higher Education Research; Huisman, J., Tight, M., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, L. Building Student Engagement and Belonging in Higher Education at a Time of Change: Final Report from the What Works? Student Retention & Success Programme; Paul Hamlyn Foundation: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Enhancing student success: Taking the classroom success seriously. Int. J. First Year High. Educ. 2012, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, M.; Longden, B. Retention and Student Success in Higher Education; Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, J.L.; Tickle, L.; Naumann, K. The four pillars of tertiary student engagement and success: A holistic measurement approach. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 46, 1207–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. The student experience of undergraduate students: Towards a conceptual framework. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2018, 42, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E.R. Framing student engagement in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, S.J.; Harper, S.R.; Pendakur, S.L. (Eds.) Student Engagement in Higher Education: Theoretical Perspectives and Practical Approaches for Diverse Populations, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Severiens, S.; Meeuwisse, M.; Born, M. Student experience and academic success: Comparing a student-centred and a lecture-based course programme. High. Educ. 2015, 70, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, L. A predictive model of student satisfaction. Ir. J. Acad. Pract. 2016, 5, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Terenzini, P.T.; Reason, R.D. Toward a More Comprehensive Understanding of College Effects on Student Learning. In Proceedings of the CHER 23rd Annual Conference, Effects of Higher Education Reforms, Oslo, Norway, 10–12 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, W.H.; Chapman, E. Student satisfaction and interaction in higher education. High Educ. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.; Mcleay, F.; Woodruffe-Burton, H. Dimensions driving business student satisfaction in higher education. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2015, 23, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, G.D.; Kinzie, J.; Buckley, J.A.; Bridges, B.K.; Hayek, J.C. What Matters to Student Success: A Review of the Literature (Commissioned Report for the National Symposium on Postsecondary Student Success: Spearheading a Dialog on Student Success); National Postsecondary Education Cooperative (NPEC): Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kerby, M.B. Toward a new predictive model of student retention in higher education: An application of classical sociological theory. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2015, 17, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenfield, C.; McBrayer, J.S. Institutional conditions that matter to community college students’ success. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2021, 45, 718–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V.; Pusser, B. Moving from Theory to Action: Building a Model of Institutional Action for Student Success; National Postsecondary Education Cooperative (NPEC): Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, J.P.; Eaton, S.B. A psychological model of college student retention. In Reworking the Student Departure Puzzle; Braxton, J.M., Ed.; Vanderbilt University Press: Nashville, TN, USA, 2000; pp. 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, L.G.; Conoley, C.W.; Choi-Pearson, C.; Archuleta, D.J.; Phoummarath, M.J.; Landingham, A.V. University environment as a mediator of Latino ethnic identity and persistence attitudes. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museus, S.D.; Quaye, S.J. Toward an intercultural perspective of racial and ethnic minority college student persistence. Rev. High. Educ. 2009, 33, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, D.; Sifuentez, B. Historically underrepresented students redefining college success in higher education. J. Postsecond. Stud. Success 2021, 1, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldrick-Rab, S.; Harris, D.N.; Trostel, P.A. Why financial aid matters (or does not) for college success: Toward a new interdisciplinary perspective. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research; Smart, J.C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hossler, D.; Ziskin, M.; Kim, S.; Cekic, O.; Gross, J.P.K. Student aid and its role in encouraging persistence. In The Effectiveness of Student Aid Policies: What the Research Tells Us; Baum, S., McPherson, M., Steele, P., Eds.; The College Board: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, A.; Soilemetzidis, I.; Hillman, N. The 2015 Student Academic Experience Survey; The Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, J.; Hillman, N. The 2016 Student Academic Experience Survey. Available online: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Student-Academic-Experience-Survey-2016.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Pritchard, R.M.O.; Klumpp, M.; Teichler, U. (Eds.) Diversity and Excellence in Higher Education: Can the Challenges Be Reconciled? Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Astin, A. Achieving Academic Excellence: A Critical Assessment of Priorities and Practices in Higher Education; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bahr, P.R.; Toth, C.; Thirolf, K.; Massé, J.C. A review and critique of the literature on community college students’ transition processes and outcomes in four-year institutions. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research; Paulsen, M.B., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 459–512. [Google Scholar]

- Kahu, E.R.; Picton, C.; Nelson, K. Pathways to engagement: A longitudinal study of the first-year student experience in the educational interface. High. Educ. 2020, 79, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, E.J. The role of social experience in undergraduates’ career perceptions through internships. J. Hosp., Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2013, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition, 2nd ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ertem, H.Y.; Gokalp, G. Role of personal and organizational factors on student attrition from graduate education: A mixed-model research. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Prac. 2019, 23, 903–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, P.; Callender, C.; Grove, L.; Kersh, N. Managing the Student Experience in a Shifting Higher Education Landscape; The Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, G. Personal factors predicting college student success. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2017, 69, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Institutional characteristics and college student dropout risks: A multilevel event history analysis. Res. High. Educ. 2012, 53, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Whitehead, Y. Non-academic support services and university student experiences: Adopting an organizational theory perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1692–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K.A.; Gagnon, R.J.; Anderson, D.M.; Pilcher, J.J. Enhancing the college student experience: Outcomes of a leisure education program. J. Exp. Educ. 2018, 41, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossensteyn, J.J.; Kottmann, A.; Jongbloed, B.W.A.; Kaiser, F.; Cremonini, L.; Stensaker, B.; Hovdhaugen, E.; Wollscheid, S. Dropout and Completion in Higher Education in Europe: Main Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Becher, T.; Trowler, P.R. Academic Tribes and Territories, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Berkshire, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, N.G. Triangulation and mixed methods designs: Data integration with new research technologies. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.; Goodman-Williams, R.; Feeney, H.; Fehler-Cabral, G. Assessing triangulation across methodologies, methods, and stakeholder groups: The joys, woes, and politics of interpreting convergent and divergent data. Am. J. Eval. 2020, 41, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natow, R.S. The use of triangulation in qualitative studies employing elite interviews. Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, P.; Fusch, G.E.; Ness, L.R. Denzin’s paradigm shift: Revisiting triangulation in qualitative research. J. Soc. Change 2018, 10, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, A.; Cross, W.E. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roulston, K.; Choi, M. Qualitative interviews. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018; pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Oberski, D.L.; Kreuter, F. Differential privacy and social science: An urgent puzzle. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2020, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis. An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo [Content Analysis]; Edições 70: Lisboa, Portugal, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution; GESIS: Klagenfurt, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, K. Investigating conditions for student success at an American university in the Middle East. High. Educ. Stud. 2014, 4, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, G.R. The convergent and discriminant validity of NSSE scalelet scores. J. Coll. Stud. Devel. 2006, 47, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, C.; Ramos, K. Políticas do ensino superior em Portugal na fase pós-Bolonha: Implicações no desenvolvimento do currículo e das exigências ao exercício docente [Higher education policies in Portugal in the post-Bologna phase: Implications for curriculum development and teaching requirements]. Rev. Lusófona De Educ. 2014, 28, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sá, M.J. ‘The secret to success’. Becoming a successful student in a fast-changing higher education environment. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2020, 10, 420–435. [Google Scholar]

- Elwick, A.; Cannizzaro, S. Happiness in higher education. High. Educ. Q. 2017, 71, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.H.T.; Muskat, B.; Zehrer, A. A systematic review of quality of student experience in higher education. Int. J. Qual. Ser. Sci. 2016, 8, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, C.A.; Barnes, S.; Carson, J.F.; Platt, I. Happiness as a predictor of resilience in students at a further education college. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2020, 44, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alteneiji, S.; Alsharari, N.M.; AbouSamra, R.M.; Houjeir, R. Happiness and positivity in the higher education context: An empirical study. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2023, 37, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razinkina, E.; Pankova, L.; Trostinskaya, I.; Pozdeeva, E.; Evseeva, L.; Tanova, A. Student satisfaction as an element of education quality monitoring in innovative higher education institution. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 33, 03043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atieno, O.C. An analysis of the strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research paradigms. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2009, 13, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).