Reflective Processes Promoted in the Practicum Tutoring and Pedagogical Knowledge Obtained by Teachers in Initial Training

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical References

2.1. Teaching Knowledge, Pedagogical Knowledge and Reflection as Support for Teaching

2.2. Approaches Underpinning Practice in Initial TeacherEducation and their Implications for Reflective Processes

2.3. The Tutorial Action and Its Relevance in the Practicum

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Focus

3.2. Study Context

3.3. Participants

3.4. Techniques Used

3.5. Data Analysis

3.6. Research Ethics Codes

- (1)

- Signature of informed consent prior to agreeing to take part in the interview. This document was approved by the Ethics and Biosafety Committee of the institution in which the researcher works under a Certification No. 011/19 certificate that was accepted by the funding agency of the research project, the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo de Chile (ANID).

- (2)

- Request for authorization prior to recording the interview.

- (3)

- Anonymity in the transcript: protection of the identity and intimacy of each participant and of the university considered as the study context.

- (4)

- Transcript: the transcription of the interviews was conducted verbatim, and an attempt was always made to make it as faithful as possible to the original.

4. Results

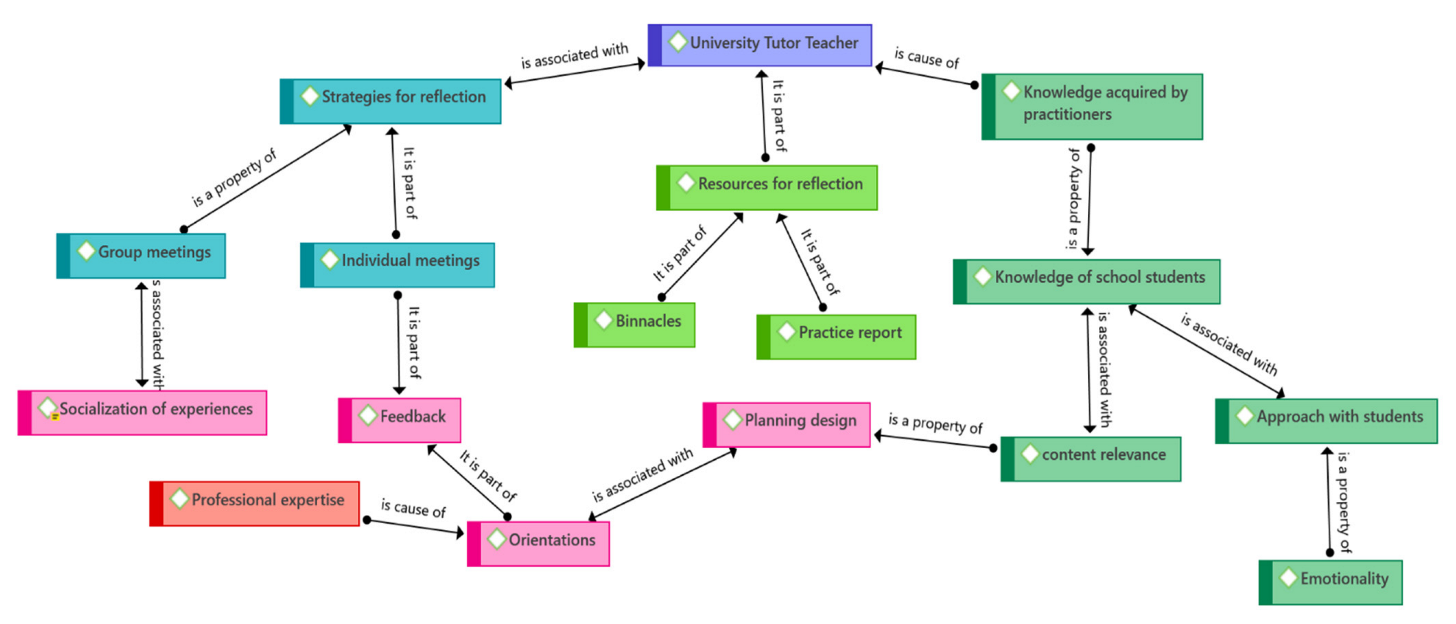

4.1. Value Attributed by Future Teachers to the Actions Implemented by the Tutor Teacher in the Promotion of Reflective Processes

4.1.1. Collective and Individual Meetings as a General Strategy That Promotes Reflective Processes

It is good to compare the processes of my classmates, sometimes to see how they are all different realities, and sometimes we do not tend to talk about our feelings, our emotions respect to the process, but it is very gratifying to be able to talk about this with the teacher and to receive guidance to improve.[21:11 - 39 in Interview 2/ECE]

It was still good to let off steam, but I don’t know if it was so theoretical, everything was much more relaxed, it was much more spontaneous, it happened.[20:16 - 43 in Interview 11/PED]

The teacher gave us some advice on how we could handle such and such a situation in case it arose, and she gave us other advice about we planned, and as we were just learning this, we were still missing some points and she was reinforcing them.[15:31 - 25 in Interview 7/PE]

All time I was being evaluated and the truth is that it is something that I really appreciate because when someone is teaching there are many things that one does not realize, that may not be correct or that I have not explained well or even used the right words, so, the role of the teacher has been very important.[27:12 - 45 in Interview 9/ECE]

When she went to observe classes or came in, always told me … “you are missing this, I liked your class, but you lacked such a thing, you should do it like this”, or she gave me options, so well, they have been a great support.[29:10 - 15 in Interview 13/PED]

4.1.2. Resources Used by the Tutor Teacher to Promote Reflection

We also had to create weekly reflection logs which meant that you had to take any of the experiences and reflect based on different criteria.[20:9 - 39 in Interview 11/ECE]

We had to deliver pedagogical reflection logs, so we analyzed experiences that we had during the week and that was very good because sometimes there is so much to do on a day-to-day basis, that there is no time to stop and analyze what you are doing, so in those blogs I think it is where I reflected the most.[23:11 - 23 in Interview 4/ECE]

You have to hand in a reflection report on the practice, you have to give some data of the establishment and specific data of the course in which we developed our practice and put, for example, our appreciation of how we felt the course took the English classes, how the course perceived them, what we thought, it was that.[15:55 - 105 in Interview 2/PE]

They also asked us to make a report, it was more general, it was more contextualized to the establishment, like our pedagogical work, but from a very superficial perspective.[20:10 - 41 in Interview 11/ECE]

At the end we had to make a full report of our practice and that’s where the qualification came in.[2:98 - 33 in Interview 1/PHG]

4.2. Knowledge Obtained/Reinforced in the Development of the Practicum with the Support of the Tutor Teacher

4.2.1. Theoretical Knowledge and Tutorial Action

Having these theoretical bases is very useful, also the subject of psychology in children, in adolescents, is a subject that is very useful when teaching, because one can already think about what one can do to capture the attention, or to achieve that there is learning on the part of the students.[15:47 - 87 in Interview 7/PE]

Now one is in charge of the course, and there I tried to remember what the educational tips of educational psychology were, how I had to show myself to the student, how I could react.[17:30 - 75 in Interview 9/PHG]

I remembered what Vygotsky said about the zone of proximal development, about having someone who helps you obtain knowledge but does not give it to you, as simple as that. I related that as I was developing learning experiences […], sometimes the principle fell into giving the answer very easily if someone did not respond and giving more signals, and then I analyzed it, and said… I must stop a bit; I must ask better questions.[23:17 - 37 in Interview 14/ECE]

I used the island of Juan Fernández when I told them about the introduction of foreign species on the island and the damage it caused, and if you only knew! …you cannot imagine many conversations, conclusions, reflections, and everything that my students got! And one of the things that I highlight the most is that at one point in a class, a student who did not participate much told me… “You know what, teacher? I always see everything you have said in class in Curanilahue,” which is where he was from, “I see how people building their houses, paving and everything else have diverted what used to be the river”, he told me, “you look at it and it’s like everything that the same people led it as they wanted, I look outside of the city and I only see pine trees teacher”. It also happens to me where I am from, I am from Cabrero, so I look around and there are pine trees everywhere, and he said “teacher, everything you say happens to me”… when the student told me that and when other students told me about what they lived, I understood what Ausubel was saying. It was all associated with their own mental processes, with their earlier experiences, with what they saw and lived with what they knew. It is the closest thing I had to the implementation of significant learning.[16:115 - 56 in Interview 8/PHG]

My supervising professor helped me in this area, in the construction of this type of reflection. His help was especially useful. I take this into consideration for my future work.[16:116 - 40 in Interview 8/ PHG]

More than anything, he guided us, for example, in the bases, he went over the issue of planning, from where to get certain resources.[24:37 - 53 in Interview-ta15/PBE]

My teacher reminded us of every week, she gave us workshops too, we reviewed the plans, she asked us how our interaction was, besides, she was also going, I mean, she went to a class to observe, so after that she could give us feedback, she explained to us what was good, what we could improve.[23:7 - 9 in Interview 14/ECE]

I truly value that my tutor focused on how we plan, how we deliver the content, if there were indicators that she considered were not right.[27:11 - 41 in Interview 18/PEP]

The other day a classmate said she had problems because a boy at her school, from her class, could not control his anger. He had very little tolerance to frustration, things like that, and at that moment, she told us “Hey! Look, I have this” and she showed us some brochures from Chile Crece Contigo, where it said how to manage these situations. Later on, she sent us the material so that we could read it.[26:21 - 46 in Interview 17/ECE]

4.2.2. Practical Knowledge Obtained with the Support of the Tutor

The teacher is a specialist in the orientation area, so more than anything else the topic was almost always focused on the emotional area, the children’s area of self-knowledge, how to work on that side […], in fact, I work a lot on the emotional development of my little ones and with that we are working on what is the specialty subject.[28:16 - 61 in Interview 19/PED]

The most significant thing that I had to learn was to organize all that full time as a teacher, it is what I could get the most meaning out of my practical experience, because it is what made me understand the most, understand and retrieve from my performance as a teacher.[16:103 - 16 in Interview 8/PHG]

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cano, M.C.; Ordóñez, E.J. Teacher training in Latin America. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 27, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedró, F. Do Universities Provide a Fairly Professional Initial Training to Teachers? Rev. Educ. Super. Y Soc. (ESS) 2020, 32, 60–88. Available online: https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/ess/index.php/ess3/article/view/233 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Valle, J.M.; Manso, J. The Practicum in initial training: Contributions of the 9:20 model of teaching competencies. Cuad. Pedagog. 2018, 489, 1–5. Available online: https://repositorio.uam.es/bitstream/handle/10486/685215/practicum_valle_CP_2018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Ávalos, B. Initial teachers’ education in Chile: Tensions between policies of support and control. Estud. Pedagógicos 2014, 40, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.C.; González, C.G.Z. Practices and conceptions of feedback in initial teacher training. Educ. Pesqui. 2019, 45, e192953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelo, C.; Vaillant, D. Initial teacher training: Complex problems disruptive responses. Cuad. Pedagog. 2018, 489, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Turra-Díaz, O.; Flores-Lueg, C. Practical training from the perspective of students of pedagogy. Ens. Avaliação Políticas Públicas Educ. 2019, 27, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirmas, C.; Cortés, I. Investigaciones Sobre la Formación Práctica en Chile: Tensiones y Desafíos; Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos para la Educación: Santiago, Chile, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Aguilar, C.; Figueroa, M. Teacher education and high stakes accountability: The case of Chile. Profesorado. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2019, 23, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional de Acreditación (CNA). Carreras de Pedagogía: Análisis de Fortalezas y Debilidades en el Escenario Actual. Serie Estudios Sobre Acreditación; CAN: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2018; Available online: https://www.cnachile.cl/SiteAssets/Paginas/estudios/Carreras-de-pedagogia_Serie-Estudios-CNA.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Flores-Lueg, C.; Turra-Díaz, O. Socio-educational contexts of teaching practices and their contributions to pedagogical training of future teachers. Educ. Rev. 2019, 35, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaete, A.; Gómez, V.; Bascopé, M. ¿Qué le piden los profesores a la formación inicial docente en Chile? In Temas de la Agenda Pública n. 86; Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile: Villarrica, Chile, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Moscoso, J. Professional internship in initial teacher training: From professional knowledge to the co-construction of situational intelligence. Pro-Posições 2021, 32, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant, D.; Marcelo, C. El ABC y D de la Formación Docente; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Correa Molina, E. The internship supervisor: Resources for an effective supervision. Pensam. Educ. Rev. Investig. Latinoam. (PEL) 2009, 45, 237–254. Available online: http://redae.uc.cl/index.php/pel/article/view/25793 (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Almeyda, L. Thrown into action. Learning to teach from the practicum experience. Estud. Pedagógicos 2016, 42, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez Núñez, G.; Campos Saavedra, D.; Suckel Gajardo, M.; Rodríguez Molina, G. Collegiate practice in initial teacher training and construction of pedagogical knowledge. RMIE Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2019, 24, 811–831. [Google Scholar]

- Gorichon, S.; Ruffinelli, A.; Pardo, A.; Cisternas, T. Relations between initial training and professional initiation of teachers. Principles and challenges for practical training. Cuad. Educ. 2015, 66, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, G.; Jara-Amigo, X. Tutoring spaces and practice building needs. Rev. Electrónica Actual. Investig. Educ. 2014, 14, 1–25. Available online: https://www.scielo.sa.cr/pdf/aie/v14n2/a26v14n2.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Hinojosa-Torres, C.; Araya-Hernández, A.; Vargas-Díaz, H.; Hurtado-Guerrero, M. Performance components in the professional practice of physical education students: Perspectives and meanings from the formative triad. Retos 2022, 43, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. The Reflective Practitioner. How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffinelli, A.; Álvarez, C.; Salas, M. Strategies to promote generative reflection in practicum tutorials in teacher training: The representations of tutors and practicum students. Reflective Pract. Int. Multidiscip. Perspect. 2022, 23, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocetti, A.; Medina, J.L. Teacher reflection and the conditions that trigger it in future teachers during their practicums. Rev. Espac. 2018, 39, 1–12. Available online: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n15/a18v39n15p02.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Vezub, L. Teacher Knowledge in Initial Education. The Perspective of Teacher Educators. Pensam. Educativo. Rev. Investig. Educ. Latinoam. 2016, 53, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Merellano-Navarro, E.; Almonacid-Fierro, A.; Muñoz Oyarce, M.F. Renaming the pedagogical knowledge: A look from the teaching practice. Educ. Pesqui. 2019, 45, e192146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckel Gajardo, M.; Rodríguez Molina, G.; Sáez Núñez, G.; Campos Saavedra, D. The role of initial teacher training in the process of building pedagogical knowledge. Actual. Investig. Educ. 2020, 20, 605–630. [Google Scholar]

- Lizana-Verdugo, A.; Muñoz-Cruz, M. Reflective Questions? A case study in teacher training. In Research Educational Scenarios: Towards a Sustainable Educativo; Romero, J.M., Navas-Parejo, M., Rodríguez Jiménez, C., Sola Reche, J.M., Eds.; Editorial Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 350–364. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffinelli, A. Educating reflective teachers: An approach under progress and dispute. Educ. Pesqui. 2017, 43, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce Díaz, N.; Camus Galleguillos, P. Teaching Practice as a Formative-Reflective axis of Initial Teacher Training. Rev. Estud. Y Exp. Educ. 2019, 18, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Espinosa, Á.L.; Rozas-Assael, T.; Cisternas-Alarcón, P.; González-Ugalde, C. Factors Associated with the Reflective Practice in Pedagogy Students. Magis Rev. Int. Investig. Educ. 2019, 11, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Linares, A.; Susinos-Rada, T. Feedback processes and formative evaluation in a reflective practicum for teachers. Meta Avaliaçã 2018, 10, 533–554. Available online: https://revistas.cesgranrio.org.br/index.php/metaavaliacao/article/view/1605/pdf (accessed on 25 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Venegas, C.; Fuentealba, A. Teaching professional identity, reflection and pedagogical practice: Key considerations for teacher training. Perspect. Educacional. Form. Profr. 2019, 58, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Mauri, T.; Onrubia, J.; Colomina, R.; Clarà, M. Sharing initial teacher education between school and university: Participants’ perceptions of their roles and learning. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2019, 25, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias Martínez, M.; Moncho Miralles, M.; Lozano Cabezas, I. Rethinking the teaching of theory through practicums: The experience of a pre-service teacher. Contextos Educ. 2019, 23, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, M.; Vergara, C.; Morales, M.A.; Orbeta, A.; Escobar, C.; Quiroga, M. Accompanying practices for tutors in teaching programs: Analysis of the quality assurance and certification devices for terminal learning. Calid. Educ. 2020, 53, 182–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concha, S.; Hernández, C.; del Río, F.; Romo, F.; Andrade, L. Pedagogic reflection based on cases and command of academic terms in students taking the fourth year of elementary teaching formation. Calid. Educ. 2013, 38, 81–113. [Google Scholar]

- Crichton, H.; Valdera Gil, F. Student teachers’ perceptions of feedback as an aid to reflection for developing effective practice in the classroom. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 38, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Fernández, Á.; Domínguez-Fernández, R. University Tutors as Facilitators of Student-teachers’ Reflective Learning During their Teaching Practice. Estud. Pedagógicos 2018, 44, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira Gonzales, M.L.; Pellerin, G.; Araújo-Oliveira, A.; Collin, S. Supporting the reflective practice of future teachers: The role of supervisor feedback. Educ. Goiânia 2020, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Flores Lueg, C.; Alvarado Retamal, T.; Gutiérrez Oyarce, T.; Medel Lillo, S. Pedagogical knowledge for early childhood education from the perspective of early childhood educators. Rev. Actual. Investig. En Educ. 2022, 22, 4–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayima, F. The role of reflective practice in mediating development of pre-service science teachers’ professional and classroom knowledge. Interdiscip. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2022, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. Wash. 1986, 2, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. Mass. 1987, 57, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, P.; Montenegro, H. Pedagogical knowledge: Exploring new approaches. Educ. E Pesqui. 2017, 43, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shulman, L. Conocimiento y enseñanza. Estud. Públicos 2001, 83, 163–196. Available online: https://www.educandojuntos.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Conocimiento-y-ensen%23U0303anza.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Tardif, M. Los Saberes de los Docentes y su Desarrollo Profesional; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado, R. Los Saberes Docentes Como Construcción Social: La Enseñanza Centrada en Los Niños; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de México, México, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. El Profesional Reflexivo. Cómo Piensan los Profesionales Cuando Actúan; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, J.; Gómez, R.; García, M.L. Pre-Service Teachers’ Practical Knowledge: Learningto Teach duringthe Practicum Experience. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2019, 21, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezub, L. Teacher Training and Professional Development faced to the new challenges posed by the school system. Profesorado. Rev. Currículum Y Form. Del Profr. 2007, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cerecedo, I. Práctica Reflexiva Mediada: Del Autoconocimiento a la Resignifcación Conjunta de la Práctica Docente; Editorial Académica Española: Beau Bassin, Mauritius, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, Á.; Gómez, V. La práctica Reflexiva. Bases, Modelos e Instrumentos; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, M.; Khanam, A. Effect of Reflective Teaching Practices on the Performance of Prospective Teachers. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 18, 32–43. Available online: http://www.tojet.net/articles/v18i1/1814.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Perrenoud, P. Desarrollar la práctica reflexiva en el oficio de enseñar. Profesionalización y razón pedagógica; Graó: Barcelona, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffinelli, A. Teaching Reflection: Development Opportunities in The Initial Teaching. Ph.D. Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.uc.cl/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11534/22001/Victoria%20Ruffinelli%20sin%20fecha.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Beauchamp, C. Understanding Reflection in Teaching: A Framework for Analyzing the Literature. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tardif, M.; Nuñez Moscoso, J. The Notion of The “Reflective Professional” In Education: Relevance, Uses And Limits. Cad. Pesqui. 2018, 48, 388–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, K. El maestro como profesional reflexivo. Cuad. Pedagog. 1993, 220, 44–49. Available online: https://www.practicareflexiva.pro/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Org-El-maestro-como-profesional-reflexivo-de-Kenneth-M.-Zeichner.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Atondo, E. The detach between theory and practice in teaching, a challenge for teachers’ schools. Rev. Qurriculum 2019, 32, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffinelli, A.; Morales, A.; Montoya, S.; Fuenzalida, C.; Rodríguez, C.; López, P.; González, C. Internship tutorials: Representations about the role of the tutor and the implemented pedagogical strategies. Perspect. Educ. 2020, 59, 30–51. [Google Scholar]

- López Martín, I.; González Villanueva, P. University tutoring as a space for personal relations. A multiple case study. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2018, 36, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza Freire, E.E.; Ley Leyva, N.V.; Guamán Gómez, V.J. Role of the tutor in teacher training. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2019, 25, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. Fenomenología de la Práctica. Métodos de Donación de Sentido en la Investigación y Escritura Fenomenológica; Editorial Universidad del Cauca: Popayán, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Carabajo, R. Pedagogical relationship: Max van Manen’s Pedagogy in the sources of educational experience. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2018, 29, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Otzen, T.; Manterola, C. Sampling Techniques on a Population Study. Int. J. Morphol. 2017, 35, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. Las Entrevistas en la Investigación Cualitativa; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, X.; Osorio, B. Quality and Rigor Criteria in the Qualitative Methodology. Gac. Pedagog. 2017, 36, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Meza, M.; Cox, P.; Zamora, G. What and how to observe interactions to understand teachers’ educational authority. Educ. E Pesqui. 2015, 41, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalza, M. Practicum and external practices in university education. Rev. Prácticum 2016, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón Soto, M. Challenges for teaching & learning in progressive practices in pre-service teachers. A qualitative approach from a Chilean university. Rev. Currículum Y Form. Profr. 2020, 24, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleyrot, E. The reflexive aim of accompanying devices in the primary school teachers’ initial training: Diachronic study by the missions of Master Trainers. Quest. Vives 2016, 24, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| University | Pedagogy Programs | Total (Institutional) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Childhood Education (ECE) | Primary Education (PED) | History and Geography (PHG) | English (PE) | ||

| University 1 (region of Ñuble) | 8 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 14 |

| University 2 (region of Biobío) | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| University 3 (region of Biobío) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 12 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 20 |

| Specific Objectives | Topics | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Identify the value attributed by teachers in professional practice to the actions implemented by the tutor teacher, related to the promotion of reflexive processes that contribute to the construction of pedagogical knowledge. |

|

|

| Characterize the pedagogical knowledge obtained by the future teachers, based on the reflective processes implemented by the tutor teacher. |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flores-Lueg, C. Reflective Processes Promoted in the Practicum Tutoring and Pedagogical Knowledge Obtained by Teachers in Initial Training. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090583

Flores-Lueg C. Reflective Processes Promoted in the Practicum Tutoring and Pedagogical Knowledge Obtained by Teachers in Initial Training. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(9):583. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090583

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlores-Lueg, Carolina. 2022. "Reflective Processes Promoted in the Practicum Tutoring and Pedagogical Knowledge Obtained by Teachers in Initial Training" Education Sciences 12, no. 9: 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090583

APA StyleFlores-Lueg, C. (2022). Reflective Processes Promoted in the Practicum Tutoring and Pedagogical Knowledge Obtained by Teachers in Initial Training. Education Sciences, 12(9), 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090583