School Organizational Culture and Leadership: Theoretical Trends and New Analytical Proposals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. A Globalizing and Elastic Topic

3.2. An Intermittent and Reactive Topic

3.3. An Interdisciplinary Topic

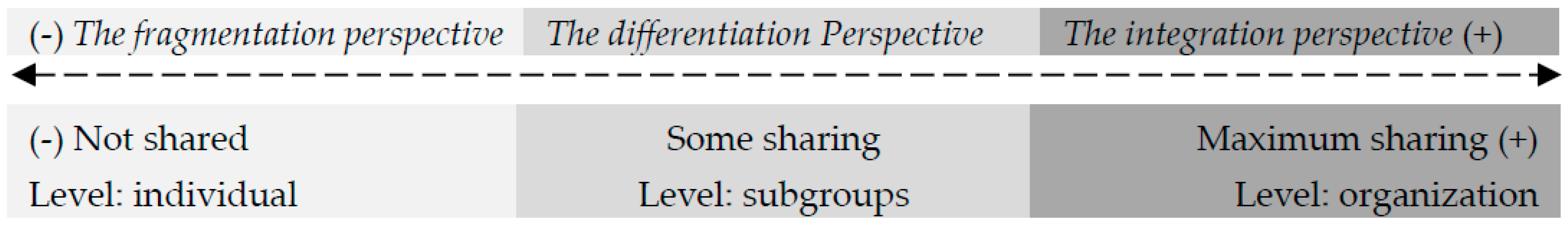

3.4. Pluralistic Expressions of Culture and Leadership

3.4.1. The Appeal of the Integration Perspective: Visionary and Charismatic Leadership?

3.4.2. The Realism of the Differentiation Perspective: Competitive and Performative Leadership?

3.4.3. The Radicalism of the Fragmentation Perspective: Scattered and Uncertain Leadership?

4. Discussion

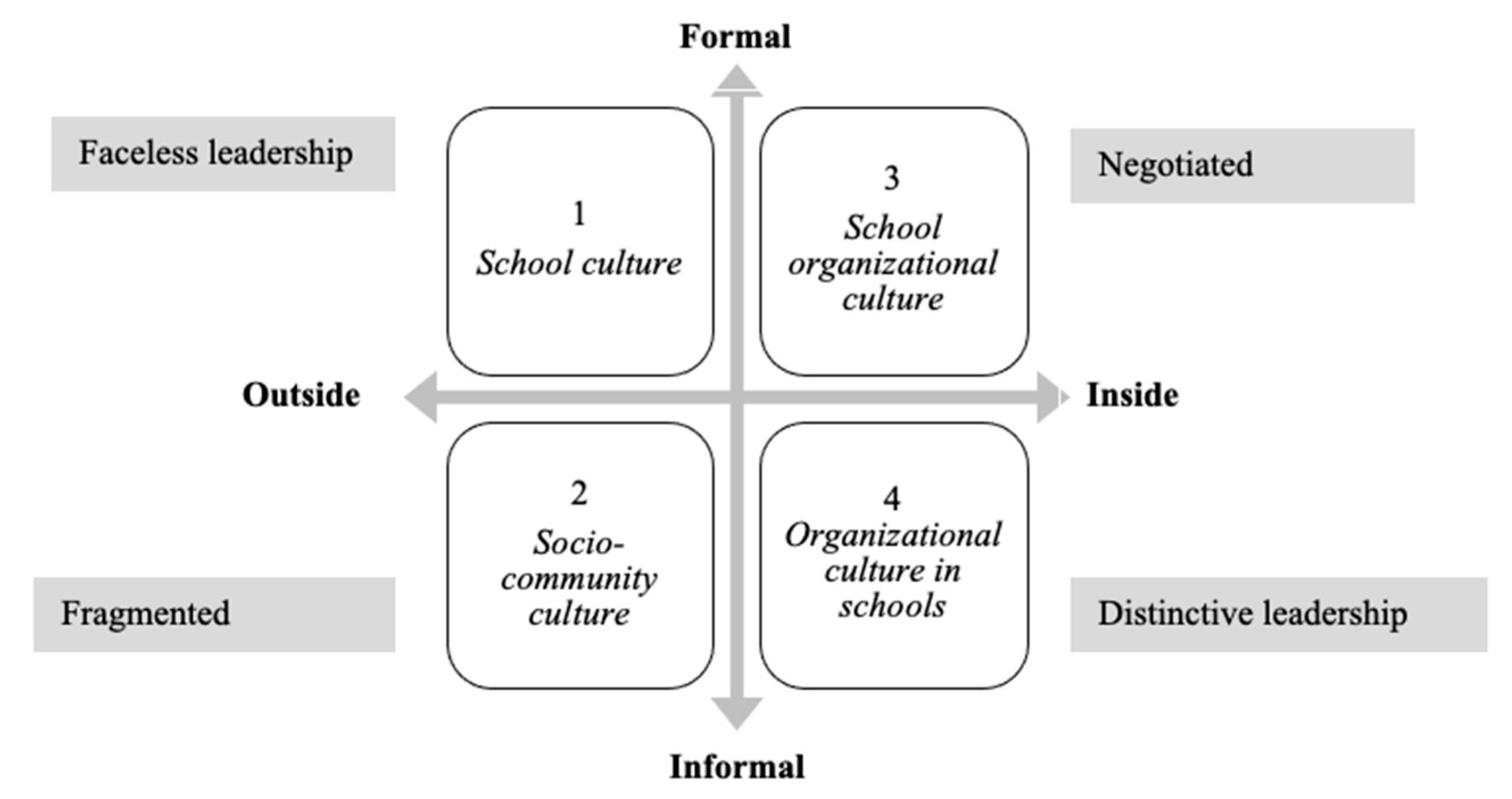

4.1. An Analytical Model for Understanding Culture in the School Setting

4.1.1. A Multilevel Approach

4.1.2. The Various Faces of Culture and Leadership

- Face 1: School culture and faceless leadership

- Face 2: Sociocommunity culture and fragmented leadership

- Face 3: School organizational culture and negotiated leadership

- Face 4: Organizational culture in schools and distinctive leadership styles

5. Conclusions–A Contextualised Approach to Culture and Leadership: Potential and Challenges

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Connolly, M.; Kruise, A.D. Organizational culture in schools: A review of widely misunderstood concept. In The Sage Handbook of School Organization; Connolly, M., Eddy-Spicer, D.H., James, C., Kruise, S., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2019; pp. 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, R.; Moos, L.; Liu, M.; Tulowitzki, P. (Eds.) The Cultural and Social Foundations of Educational Leadership. An International Comparison; Springer: Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumby, J.; Foskett, N. Power, risk, and utility: Interpreting the landscape of culture in educational leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2011, 47, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Dacin, M.T. The cultural construction of organizational life: Introduction to the special issue. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, G.; Hallett, T. Group cultures and the everyday life of organizations: Interaction orders and meso-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2014, 35, 1773–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Sveningsson, S. Changing Organizational Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Karreman, D.; Ybema, S. Studying culture in organizations: Not taking for granted the taken-for-granted. In The Oxford Book of Management; Wilkinson, A., Armstrong, S.J., Lounsbury, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdougall, M.; Ronkainen, N. Organisational culture is not dead…yet: Response to Wagstaff and Burton-Wylie. Sport Exerc. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 15, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Smircich, L. Concepts of culture and organizational analysis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smircich, L. Studying organizations as cultures. In Beyond Method: Social Research Strategies; Morgan, G., Ed.; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1983; pp. 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey-Bass Publishers: São Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, P.J.; Moore, L.F.; Louis, M.R.; Lundberg, C.C.; Martin, J. (Eds.) Organizational Culture; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, P.J.; Moore, L.F.; Louis, M.R.; Lundberg, C.C.; Martin, J. (Eds.) Reframing Organizational Culture; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Berg, P.O. Corporate Culture and Organizational Symbolism: An Overview; Walter de Gruyter: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M. Understanding Organizational Culture; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. Cultures in Organizations. Three Perspectives; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. Organizational Culture. Mapping the Terrain; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, D.H. The Challenge for the Comprehensive School. Culture, Curriculum and Community; Routledge & Kegan Paul Lda.: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, T.; Kennedy, A.A. Culture and school performance. Educ. Leadersh. 1983, 40, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Deal, T.; Kennedy, A.A. Corporate Cultures. The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Westoby, A. (Ed.) Culture and Power in Educational Organizations; Open University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J.A. A perspective on organizational cultures and organizational belief structure. Educ. Adm. Q. 1985, 31, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.J. Corporate culture, schooling, and educational administration. Educ. Adm. Q. 1987, 23, 79–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, F. Conceptions of school culture: An overview. Educ. Adm. Q. 1987, 23, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, R.F. Reform and the culture of authority in schools. Educ. Adm. Q. 1987, 23, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalin, P.; Rolff, H.-G. Changing the School Culture; Cassell: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, J. (Ed.) School Culture; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.; James, C.; Beales, B. Contrasting perspectives on organizational culture change in schools. J. Educ. Change 2011, 12, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Torres, L.L. Cultura Organizacional em Contexto Educativo. Sedimentos Culturais e Processos de Construção do Simbólico Numa Escola Secundária; Centro de Investigação em Educação da Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlstetter, P.; Lyle, A.G. Inter-organizational networks in education. In The Sage Handbook as School Organization; Connolly, M., Eddy-Spicer, D.H., James, C., Kruise, S., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2019; pp. 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodway, J.; Daly, A.J. Defining schools as social spaces: A social network approach to researching schools as organizations. In The Sage Handbook As School Organization; Connolly, M., Eddy-Spicer, D.H., James, C., Kruise, S., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2019; pp. 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Harris, A.; Hadfield, M.; Tolley, H.; Beresford, J. Leading Schools in Times of Change; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. Liderar Numa Cultura de Mudança; Edições ASA: Porto, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A.; Fink, D. Liderança Sustentável; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reitzug, U.C.; Reeves, J.E. “Miss Lincoln Doesn’t teach here”: A descriptive narrative and conceptual analysis of a principal’s symbolic leadership behavior. Educ. Adm. Q. 1992, 28, 185–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergiovanni, T. O Mundo da Liderança. Desenvolver Culturas, Práticas e Responsabilidade Pessoal nas Escolas; Edições ASA: Porto, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sergiovanni, T. Novos Caminhos Para a Liderança Escolar; Edições ASA: Porto, Portugal, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barzanò, G. Culturas de Liderança e Lógicas de Responsabilidade. As Experiências de Inglaterra, Itália e Portugal; Fundação Manuel Leão: Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Derouet, J.-L.; Normand, R. (Eds.) La Question du Leadership en Education. Perspectives Européennes; Academia-L’Harmattan S.A.: Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lindle, J.C. Political Contexts of Educational Leadership; Routedge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.L. A ritualização da excelência académica. O efeito cultura de escola. In Entre Mais e Melhor Escola em Democracia. A Inclusão e a Excelência no Sistema Educativo Português; Torres, L.L., Palhares, J.A., Eds.; Mundos Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, L.L.; Palhares, J.A. A Excelência Académica na Escola Pública Portuguesa; Fundação Manuel Leão: Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Quaresma, L. A excelência académica em liceus públicos emblemáticos do Chile: Perspetivas à luz do olhar de directores e professores. In A Excelência Académica na Escola Pública Portuguesa; Torres, L.L., Palhares, J.A., Eds.; Fundação Manuel Leão: Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal, 2016; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.; Frost, P.J.; O’Neill, O.A. Organizational culture. Beyond struggles for intellectual dominance. In The Sage Handbook of Organization Studies; Clegg, S., Hardy, C., Lawrence, T., Nord, W., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2006; pp. 725–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldridge, V.J.; Deal, T. (Eds.) The Dynamics of Organizational Change in Education; McCutchan Publishing Corporation: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, W.G.; Gresso, D.W. Cultural Leadership: The Culture of Excellence in Education; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.D.; Deal, T.E. The Shaping School Culture Fieldbook; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, T.; Bell, L.; Bolam, R.; Ron, G.; Ribbins, P. (Eds.) Educational Management. Redefining Theory, Policy and Practice; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.L.; Palhares, J.A. Cultura, formação e aprendizagens em contextos organizacionais. Rev. Crítica de Ciênc. Soc. 2008, 83, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolman, L.G.; Deal, T.E. Reframing Organizations. Artistry, Choice and Leadership; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, H.D.; Firestone, W.A.; Rossman, G.B. Resistance to planned change and the sacred in school cultures. Educ. Adm. Q. 1987, 23, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Sveningsson, S. Changing Organizational Culture. Cultural Change Work in Progress; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T. Conceptions of the leadership and management of schools as organizations. In The Sage Handbook of School Organization; Connolly, M., Eddy-Spicer, D.H., James, C., Kruise, S., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2019; pp. 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, G.L.; Chang, E. Competing narratives of leadership in schools: The institutional and discursive turns in organizational theory. In The Sage Handbook of School Organization; Connolly, M., Eddy-Spicer, D.H., James, C., Kruise, S., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2019; pp. 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.L.; Palhares, J.A.; Afonso, A.J. The distinction of excellent students in the Portuguese state school as a strategy of educational marketing accountability. Educ. Asse. Eval. Acc. 2019, 31, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawhinney, H.B. Rumblings in the cracks in conventional conceptions of school organizations. Educ. Adm. Q. 1999, 35, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, M.; Hlousková, L.; Novotny, P.; Zounek, J. Em busca do conceito de cultura escolar: Uma contribuição para as discussões actuais. Rev. Lusófona Educ. 2007, 10, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, J. Políticas Educativas e Organização Escolar; Universidade Aberta: Lisboa, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dominique, J. La culture scolaire comme objet historique. Paedagog. Historica. Int. J. Hist. Educ. 1995, 31, 353–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.C. Elementos da hiperburocratização da administração educacional. In Trabalho e Educação no Século XXI: Experiências Internacionais; Lima, L.C., Júnior, J.R.S., Eds.; EJR Xamã Editora Lda.: São Paulo, Brasil, 2012; pp. 129–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lahire, B. O Homem Plural. As Molas da Ação; Instituto Piaget: Lisboa, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lahire, B. Retratos Sociológicos. Disposições e Variações Individuais; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| Degree of Formality | Analytical Levels | Place of Production |

|---|---|---|

Formal Structure Informal Action | School culture | Outside School Inside school |

| School organizational culture | ||

| Sociocommunity culture | ||

| Organizational culture in schools |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres, L.L. School Organizational Culture and Leadership: Theoretical Trends and New Analytical Proposals. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12040254

Torres LL. School Organizational Culture and Leadership: Theoretical Trends and New Analytical Proposals. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(4):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12040254

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres, Leonor L. 2022. "School Organizational Culture and Leadership: Theoretical Trends and New Analytical Proposals" Education Sciences 12, no. 4: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12040254

APA StyleTorres, L. L. (2022). School Organizational Culture and Leadership: Theoretical Trends and New Analytical Proposals. Education Sciences, 12(4), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12040254