Abstract

Knowledge influences policy development and policies impact disabled people. Scientific and technological advancements, including neuro-advancements and their governance, have social implications for disabled people. However, knowledge is missing on this topic. Although efforts are underway to increase the number of disabled academics, the numbers remain low. Engaging undergraduate disabled students in knowledge production, especially research, could decrease the knowledge deficit and increase the pool of disabled students considering an academic career. We performed 10 semi-structured interviews of disabled students to understand the reality of undergraduate disabled students as knowledge producers, including researchers. Using a directed thematic content analysis, we found that participants felt that undergraduate disabled students were insufficiently exposed to and supported in the identity of being knowledge producers including researchers. Participants identified ethical, legal, and social implications of science and technology and argued that undergraduate disabled students and disabled people have a role to play in the discussions of these. Exposing disabled students at the undergraduate and high school level to knowledge production including researcher identity could increase the numbers of undergraduate disabled researchers, disabled academics, and disabled students doing research in the community after graduation and decrease the knowledge gaps around the social situation of disabled people.

1. Introduction

Policy developments are guided by knowledge [1], and policies impact disabled people [2]. Academic knowledge that informs policy is missing around the social situation of disabled people [3,4,5,6,7]. Science-related knowledge production and knowledge production for science and technology governance is seen as a political and social process [8,9,10,11,12,13,14] and disabled people are impacted by what knowledge is produced. Disabled people are experts of their lived experiences [4,15,16]. Therefore, undergraduate disabled students are one group that could produce knowledge to decrease the existing gap and to produce knowledge relevant to disabled people.

Research experience, one form of knowledge production, is important to the undergraduate student experience [17]. Undergraduate disabled students are part of the undergraduate student cohort; however, “there is a significant gap in academic literature around undergraduate disabled students as knowledge producers including as researchers” [18] (p. 12). Disabled students at all levels face various challenges within higher education settings [19,20,21,22,23,24], as do disabled academics [24,25,26,27]. Increasing the number of undergraduate disabled students engaged in research might increase the number of disabled students that pursue graduate studies and consider an academic career [18,24].

Role theory suggests that one’s role impacts expectations pertinent to the behaviour of the individual and the individual’s expectations of others [28]. Being a knowledge producer including being a researcher is one role undergraduate disabled students could identify with. This study aims to understand the perspectives of disabled students on the reality of undergraduate disabled students as knowledge producers, including as researchers. We discuss our findings through role and identity theory and the science and technology governance discussions around knowledge production. The following research question was investigated: What are the views of participants on undergraduate disabled students as knowledge producers, as researchers, in general, and especially in relation to science and technology including neurotechnology, and the governance of science and technology?

1.1. Knowledge Production and Science and Technology Governance

Science knowledge production and knowledge production for science and technology governance is a political and social process [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,29]. Knowledge governance concerns itself with the impact of knowledge production and dissemination to achieve policy and societal change [30] and the interaction “between scientific and citizen groups [is seen] to be a crucial element of the modern ways of knowledge production and governance” [31] (p. 1). Disabled people are often at the receiving end of narratives on how to advance science and technology, such as neurotechnology, robotics, and artificial intelligence. However, problems with the coverage are noted namely a medical imagery bias of the disabled person, a predominantly techno-optimistic narrative, and a low level of engagement with science and technology causing potential social problems for disabled people [32,33,34,35,36,37]. Role theory suggests that expectations of oneself are influenced by the role expectations of others [38]. Undergraduate disabled students are well positioned to become involved in various roles within knowledge production of the missing data regarding the social situation of disabled people and the social impact of different sciences and technologies on disabled people. The question is whether undergraduate disabled students are seen and do see themselves as having a role in scientific knowledge production and especially knowledge production for science and technology governance?

1.2. Students as Knowledge Producers, Including Researchers

Students can be knowledge producers [39,40], including being researchers [7,41,42,43,44,45]. There are many benefits to instilling a research identity into undergraduate students [7,46,47,48,49,50,51], and shaping a student’s research identity can impact their career choices [52,53,54,55]. Disabled students are part of the student cohort. However, disabled people continue to face many systemic challenges in higher education in Canada [19,56] and beyond [18,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74], which shapes the individual’s vision of themselves as knowledge producers including being researchers, either as a career at the university or in the community after graduation. In Canada, where education is the responsibility of the individual provinces which makes policy consistency throughout the country challenging, less than half to a quarter (depending on severity classification) of disabled youth who want to go to university enrol in university [75,76,77]. Many do not finish their degree, and the level of university education for disabled people is lower than the non-disabled population [75,76,77]. Furthermore, only 13.9% of disabled people have a university degree in Canada [77], 19.4% of undergraduate students and 11.9% of graduate students at U.S. universities have disabilities [78], and 7.8% of the student cohort are disabled in the UK [60].

Identity theory suggests that the role one occupies within society impacts one’s perception of ‘self’ [79] but there is little engagement in the academic literature around the role and identity of undergraduate disabled students as researchers [18] suggesting that there is no push for or expectations of undergraduate disabled students being researchers which might influence negatively whether undergraduate disabled students internalize the identity of being researchers. It is recognized that there is still a lack of disabled academics everywhere including Canada [25,26,27]. For example, a recent Statistics Canada survey found that 6.7% self-identify as a university professor, instructor, teacher, or researcher [80]. However, no numbers are given for the individual positions including the different levels of professorships and different types of ‘disabilities’. Given the broad definition of ‘disability’ in Canada [80,81] and elsewhere [82,83,84,85,86] with people linked to each of the classifications facing different realities and challenges, having one number for example for disabled faculty is not sufficient [24]. Indeed, the lack of data in general is one big problem for implementing equity, diversity, and inclusion policy frameworks whose goal is to increase the numbers of disabled students, academic and non-academic staff [24]. Increasing the pool of undergraduate disabled researchers is needed to attain such a goal [18]. However, given identity theory, this will not happen if this identity and role is not actively empowered and pushed by others and undergraduate disabled students are not motivated. Undergraduate disabled students due to their lived experience are perfectly situated to add lenses to the production of knowledge in relation to the lived reality of disabled people that might be much more difficult to achieve otherwise. They might envision research questions that others who do not have the lived experience would not think of and they are in a good position to call out unconscious biases in many research projects and research questions.

Producing knowledge is one avenue through which students can influence discourses, initiate change, including policy change, and fulfil their role as active citizens [87,88]. This includes disabled undergraduate students [18]. Undergraduate disabled students in theory have access to tools such as academic databases and research method training which most disabled people who are not students do not (albeit the access also varies for disabled students depending on where they are situated) [18]. Discussions focusing on members of the public producing research-based knowledge using names such as community scholar, citizen science, and other terms are increasing [7,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103]. Undergraduate disabled students can use their university training in knowledge production if they received it and their research experience if they obtained it in their undergraduate time to be community scholars and perform citizen science if they choose to work in the community after graduation [7,18].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

We used a qualitative study design using a directed thematic content analysis approach for our research study. It is the most appropriate approach because it allows for an in-depth exploration of undergraduate disabled student experiences related to the research question [104,105]. We conducted face-to-face and virtual semi-structured interviews to collect the data. Interviews were chosen as our method of data collection because they allow for conversations to be guided towards answering the research question and give participants the opportunity to elaborate on issues most important to them [105].

2.2. Research Question and Questionnaire

The following research question was investigated: What are the views of participants on undergraduate disabled students as knowledge producers, as researchers in general and especially in relation to science and technology including neurotechnology and the governance of science and technology? We developed a set of interview question designed to elicit information pertinent to our research question covering the following topics: (a) demographics, (b) views on and involvement in knowledge production which covered whether participants see themselves already or could envision themselves as knowledge producer, (c) community-based and academic knowledge production which included participants’ views on the importance of these two areas of knowledge production, whether they can see themselves producing knowledge of these types, (d) research activities which included whether participants already perform research and if yes on what topic and if not why not and what topic participants would like to research, (e) knowledge production covering technology and neurotechnology which included whether they already performed research in this area or could see themselves performing research in these areas and asking for the reason of why yes or no, (f) the ethical, legal, social, and economic implications of technology and neurotechnology which included whether they already performed research in this area or could see themselves performing research in these areas and asking for the reason of why yes or no, and (g) governance of science and technology, which included whether participants felt technologies in general and neurotechnologies pose ethical, legal, or social issues in general and for disabled people in particular. We did not perform a pretest with the questions.

2.3. Participants and Sampling

Expert snowball sampling was used for recruitment [104] and generated 10 participants. We used this form of recruitment because participants are selected based on the ‘information-rich’ accounts that they can provide [105]. Our inclusion criteria were that participants had to be undergraduate or graduate disabled students in Canada. Interviews took place between 8 February 2019 and 12 November 2019. Each interview ranged from approximately 42 to 75 min long and was recorded using a digital audio recorder.

2.4. Data Analysis

Express Scribe® playback software was used to orthographically transcribe each interview verbatim into Microsoft® Word. This style of transcription focuses on what the participant said (audio recording) rather than how the participant said it [105]. Each participant was given a fake name “Participant 1, Participant 2, etc.”. The transcript of each interview was uploaded as a PDF document into ATLAS.ti-8®, which is a qualitative data analysis software. We performed a directed thematic analysis [105,106] because (1) meaning can be derived from each interview; (2) it allows for an inductive approach to identifying themes based on verbal content in a ‘bottom-up’ fashion; (3) it permitted us to understand in depth the themes of participant responses [105,107]. We followed the six-phase thematic analysis process outlined by Braun and Clarke [106].

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, University of Calgary (REB17-0785) on 23 February 2018. Voluntary, informed written and verbal consent was obtained from each participant at the beginning of each interview. To ensure the anonymity of participants, each interview was anonymized using the pseudo-names “Participant 1, Participant 2, etc.”, and all coding was performed using the pseudo-names. Given the small sample size, all identifiable information was anonymized to protect the privacy of participants, and identifiable information (i.e., age, degree of study, etc.) was not linked to specific participants within the results section to ensure confidentiality.

2.6. Trustworthiness Measures

Trustworthiness measures include confirmability, credibility, dependability, and transferability [108,109,110]. Differences in codes and theme suggestions of the qualitative data were few and discussed between the authors and revised as needed to ensure credibility and dependability. Confirmability is also evident in the audit trail made possible by using the Memo and coding functions within ATLAS.Ti 8™.

2.7. Limitations

The sample of our study is relatively small, does not cover all disabilities, and is focused on Canada. As such certain content might not have come up. Our purpose was not to generalize the views of our participants to all disabled students. As for transferability [108,109,110], however, our study allows for transferability such that our study can be used to guide further similar studies, for example, studies that focus on deaf students.

3. Results

We structured the results section into five sections: (a) demographics (Section 3.1), (b) views on and involvement in knowledge production (Section 3.2 with Section 3.2.1 Understanding of Knowledge Producer Identity, Section 3.2.2 Involvement in Knowledge Production, Section 3.2.3 Barriers to Knowledge Production, and Section 3.2.4 Factors that Entice Disabled Students to be Involved in Knowledge Production), (c) general views and perception of technology including neurotechnology (Section 3.3 with Section 3.3.1 Views and perception of Technology, Section 3.3.2 Views and perception of neurotechnology), (d) ethical, social, legal, and economic implications of technology including neurotechnology (Section 3.4 with a separation into Section 3.4.1 Ethical, Section 3.4.2 Social, Section 3.4.3 Legal, and Section 3.4.4 Economic), and (e) governance of technology including neurotechnology and governance of knowledge production (Section 3.5 with Section 3.5.1 Governance of Technology including Neurotechnology and Section 3.5.2 Intersection of Knowledge Production and Governance).

For all but the demographic section, we first show a table with the themes we found and then give example quotes from our participants related to the themes found.

3.1. Demographics

A total of 80% of our participants were female and 20% were male. The gender disparity within our sample was not intentional. There is a lack of research covering the gender of disabled students in higher education; however, one study suggests that the majority of the disabled student cohort in higher education is female [60]. A total of 80% of our participants were undergraduate students and 20% graduate students. A total of 50% were 18 to 25 of age, 30% were 26–33, and 20% older, 33.40% identified as having a physical disability, 40% a mental health issue, 30% a learning disability, 20% a visual impairment, and 10% as having ADHD. As for degrees, 70% were from Disability Studies, 20% from Psychology and Sociology each and 10% each from Biochemistry, Computer Sciences, Education, Gender Studies, International Relations, Management, and Political Sciences. The participants came from Alberta (4), British Columbia (2), and one each from Manitoba, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, and Ontario.

The remaining findings in this study are presented in three sections. Section 3.2 covers the understanding and perspectives of participants on knowledge production. Section 3.3 covers the understanding and perspectives of participants on technology, neurotechnology, and the ethical, legal, social, and economic implications of these technologies. Section 3.4 covers the views of participants on technology and knowledge production governance.

3.2. Knowledge Production

3.2.1. Understanding of Knowledge Producer Identity

Table 1 summarizes participants’ definitions of knowledge production; 60% of participants defined it as producing new knowledge or research. A total of 60% stated that anyone can be a knowledge producer, while 90% self-identified as a knowledge producer based on their past experiences in a research setting, in a specific course, or their future career goals. All identified the importance of academic knowledge production and community-based knowledge production. A total of 40% identified problems within knowledge production: exclusion of disabled people (20%), problems linked to bias (10%), and futility of some research (10%).

Table 1.

Overview of themes identified within the perspectives related to knowledge production.

Who Can Be a Knowledge Producer?

In total, 60% of participants stated that anyone can be a knowledge producer and 30% stated that individuals need background knowledge on the topic. A total of 20% suggested that everyone’s experience has value, and 20% stated that disabled people are experts of their lived experiences.

P8: … “I often use the word that we are because of our lived experience, we are experts… we are the experts and the knowledge producers of our own experience”.

Self-Identifying as a Knowledge Producer

Nintey percent of participants self-identified as a knowledge producer, but only one undertook a research project outside coursework as an undergraduate. According to participants, the research identity narrative undergraduate disabled students are exposed to does not prompt undergraduate disabled students to think of themselves as potential researchers. A total of 60% had experience producing knowledge in an academic setting, one participant had experience performing research within a course, and 30% referenced a particular course they took in which they felt confident in the material, and it was this experience that shaped their knowledge producer identity. Forty percent including the two graduate students, indicated that they plan to pursue a career in producing academic research.

Role of Academic Knowledge Production

All participants consider academic research as a form of knowledge production. A total of 80% identified that academic knowledge production informs policy, 20% suggested that it provides a foundation for community change, and 10% suggested that it is an evolving field.

Role of Community-Based Knowledge Production

Only 10% of participants identified important features of community-based knowledge production, while 30% suggested that it is more implementable than academic-based knowledge production, 40% suggested that it is more realistic at the community level than academic-based, and 30% suggested that it provides diverse perspectives on a given topic.

P8: … “I think that having the intersection of the community with academia makes it stronger because the community is the one impacted by knowledge if it at all impacts policy or legislation and people who are in the community are the knowers.”

Problems with Knowledge Production

A total of 40% of participants identified problems within knowledge production, including the problem of bias (10%), the lack of importance/relevance of some research (10%), and the under-representation of disabled people (20%).

P2: … “I think people with disabilities are always undermined and they are not listened to, they are not included.”

3.2.2. Involvement in Knowledge Production

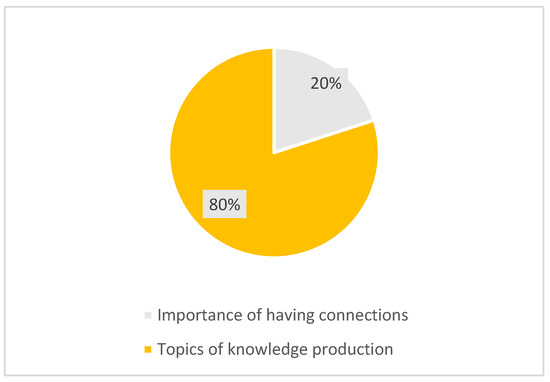

Figure 1 shows that 20% of participants stated that getting connected within the research community is important to become involved, and 80% suggested that the research topic impacts one’s involvement.

Figure 1.

Two main subthemes related to participants being involved in knowledge production.

Of the participants, 30% had been involved in a research study as a participant and 60% including both graduate students had experience working on an academic research project as undergraduates. However, of these undergraduate research projects, only 20% were outside course-based work (both by undergraduate student participants), 20% of which were undergraduates, one is a master’s student, and one is a PhD candidate. Only 10% became involved in research during their undergraduate degree because a colleague suggested becoming involved in research to upgrade their bachelor’s degree into an Honour’s Bachelor’s degree. Another undergraduate participant became involved in knowledge production during their undergraduate degree because a colleague invited the participant to join a research group. The two graduate students became involved in knowledge production because a professor suggested it. A total of 60% of our participants had experience in community-based knowledge production, 40% of which were undergraduates, one was a graduate student, and one was a PhD candidate. For example, one graduate participant is involved in writing public awareness pieces and others are working with the government on policy development.

In total, 20% of participants suggested that having connections within the research community is important. For example,

P2: … “In order for someone to take them on as a researcher, usually students that start as a researcher did it in high school or has a sibling who can connect them.”

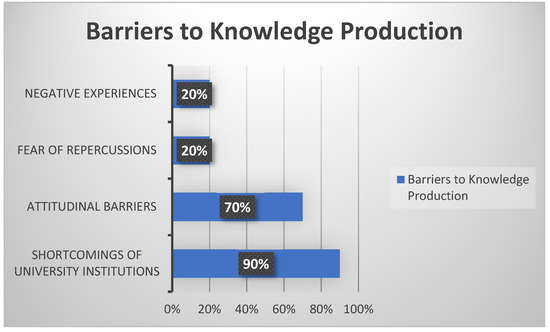

3.2.3. Barriers to Knowledge Production

Figure 2 outlines the four main barriers within knowledge production mentioned by participants. Within these four main barriers under the barrier theme of “Shortcomings of university institutions” the subthemes were: Lack of opportunity (40%), Lack of exposure to research identity (30%), Lack of accommodation (20%), and Negative Experience (20%). Under the barrier theme “Attitudinal barriers” (70%) the subthemes were: Academic merit (70%), Subjectivity of selection process (20%), Favouritism towards science and medical research (20%). Under the barrier theme “Fear of repercussions” (20%) the subthemes were: Afraid to share lived experiences (20%) and Fear of government (10%).

Figure 2.

Overview of subthemes related to barriers to knowledge production.

Shortcomings of University Institutions

A total of 30% of participants felt that they lacked exposure to a research identity, and 20% suggested that there is a lack of opportunity to become involved.

P4: … “I think one of the barriers that I have experiences just as a student and just as a woman with a disability is that there hasn’t been a lot of opportunities to take part in research.”

P4: … “there is a significant amount of onus on post-secondary institutions that those opportunities are there and again with the whole virtual aspect of it… one of the barriers that I face just within the community is transportation.”

Participants were ambiguous regarding the accommodations provided by the university institution. One undergraduate participant indicated the university was accommodating in some ways but not others. For example, the washrooms facilities were inaccessible, but they also expressed that,

P1: … “the accessibility department at the university of X is exceptional… if I had a problem with accessibility to any of the classrooms anything or even on textbooks are too heavy.”

A graduate student participant expressed negative regard towards the university institution’s accommodation.

P7: … “Well, it starts with my first run with grad school in 2011 when I ended up burning out, I wasn’t getting support. There was no idea of how to accommodate a student with disabilities in graduate studies.”

Attitudinal Barriers

A total of 70% of participants stated that they experienced attitudinal barriers in knowledge production. For example,

P6: … “It can be an attitudinal barrier can maybe be a big problem in terms of being able to be engaged in knowledge production particularly if you are in an environment if you don’t feel valued.”

Likewise, 70% of participants suggested that academic merit is a determining factor if one can be involved in knowledge production, and 20% experienced feeling overlooked.

P6: … “I don’t think that it caters to or against, but I do think it caters to a population in which academic achievement is um primary.”

A total of 20% of participants suggested that becoming involved in research can be challenging because being accepted to a research position can be highly subjective and 20% expressed that science and medical research are highly favoured in research communities.

P8: … “It is so hard to be valued for the knowledge that we come with. Whether it’s our own experience knowledge or if we have one or two or three degrees or special training”

P2: … “I think that the campus actually does not do a good job of incorporating any other discipline other than health sciences into research and it is disheartening.”

Fear of Repercussions and Negative Experiences

A total of 20% of participants stated that because of negative experiences in their past, they fear sharing the lived experiences and 10% stated they fear sharing their experiences because it may affect their government funding.

P8: … “I realized there were so many personal barriers I had experienced and there were so many times I was afraid to speak up.”

Likewise, 20% of participants had negative experiences in knowledge production.

P8: … “the barriers I have experienced have been in going through ethics… Where ethics committees make assumptions… But from their perspective there is this protectionism and this paternalism that occurs, and it was a very frustrating process… it was too difficult to deal with the ethics processes and be the one that you know is breaking down those barriers.”

3.2.4. Factors That Entice Disabled Students to Be Involved in Knowledge Production

Table 2 indicates how participants are enticed to be involved in knowledge production is dependent on opportunities available to become involved (60%), development of a research identity (70%), and the topic of study (80%).

Table 2.

Overview of themes related to factors that entice disabled students to be involved in knowledge production.

Opportunities to Become Involved

A total of 20% of participants said that opportunities to become exposed to research and attend seminars are important to getting people involved in knowledge production.

P6: … “I think there is lots opportunity in terms of like having exposure and like overall like the university set up a lot of seminars so you can go to these things and can be exposed to research.”

Meanwhile, 30% stated that guidance is necessary when beginning knowledge production.

P9: … “I’d just say like really offering like support and guidance throughout the whole process I guess the first time you run through it and make sure you really have a thorough understanding.”

A total of 30% said that the willingness of research groups to accommodate is impactful.

P4: … “So even if there are some barriers to learning, they make, they have to be willing to try and see if they can get supports to overcome those barriers.”

Developing a Research Identity

A total of 30% of participants suggested that it is important to get students involved and excited about knowledge production.

P8: … “I think it is really critical that departments engage in cohorts and identify student areas of passion because I think that is when people get excited about knowledge production.”

A total of 20% felt that the role of a research mentor is critical for encouraging undergraduate disabled students to produce knowledge.

P8: … “there I became very engaged in my department … and our whole department was really incredible. It really helped me consider doing a masters and such.”

Additionally, 30% suggested that a sense of community within research groups is also enticing.

P1: … “it’s not like you are just a student pushing through. He is very much into academic family.”

A total of 40% linked knowledge production to advocacy in the disability field.

P2: … “People with disabilities can only advocate for people with disabilities…Without them advocating for themselves, engineers or not anybody wouldn’t know what gaps there are to fill.”

Topic of Study

A total of 80% of participants stated that being interested in the topic is important, 80% suggested that sharing their lived experience to improve the lives of others is enticing, and 40% suggested that knowing the knowledge they are producing is impactful to enticing them.

P3: … “I guess what enticed me was wanting to be part of the difference in the world.”

3.3. General Views and Perception of Technology Including Neurotechnology

Table 3 indicates that 100% of participants stated they are interested in technology in general and its impacts and had been exposed to it. 10% stated they were interested in neurotechnology, while only 40%% stated had been exposed to neurotechnology. Participants outline positive (30%/30%) and negative impacts (100%/50%) of technology/neurotechnology.

Table 3.

Overview of themes related to views and perceptions of technology, including neurotechnology.

3.3.1. Views and Perceptions of Technology

All participants identified that there are negative social impacts of technology such as social robots and that technology can create greater disparity between people in poverty and people who can afford the technology. For example,

P10: … “now everything has to be done with technology to apply for jobs, you can’t just walk into apply for a job, you have to do it online, which creates barriers for people who are below the poverty line”

Additionally, 30% identified positive impacts, such as the new opportunities it can provide. Of them, 10% suggested that technology can improve accessibility, 10% suggested that technology improves communication, and 10% suggested that technology creates new opportunities.

A total of 10% of participants suggested that users of technology have to learn to trust technology, while 20% stated that disabled people use technology to improve functionality, while able-bodied people use technology for enhancement. A total of 70% stated that they had considered the ethical, social, legal, and economic implications of technology, but only 10% had been exposed to these topics in a course during their post-secondary education.

3.3.2. Views and Perception of Neurotechnology

All participants stated interest in neurotechnology. For example, one participant self-educated on neurotechnology:

P9: … “It definitely something of interest for me and I have done a lot of reading about it.”

While 100% of participants expressed interest in neurotechnology, 30% felt that because they do not personally use neurotechnology it does not impact them. For example,

P10: … “I haven’t been exposed to it. I also don’t really have a lot of technology for my disability…I would have no clue about anything neuro just because it has not impact on my life and I have never had to think about it.”

A total of 50% of participants outline negative impacts of neurotechnology: creating a disparity between people who can or cannot afford it (20%), creating a social divide between people (20%), and infringing on people’s rights (10%). A total of 30% of participants outlined positive impacts of neurotechnology: using neurotechnology to make disabled people normal (10%), enhance able-bodied people (10%), and maintain able-bodied people’s ‘normal’ (10%).

3.4. Ethical, Social, Legal and Economic Implications of Technology Including Neurotechnology

Table 4 indicates that most participants responded that technology poses ethical, social, legal, and economic issues for both disabled people and people without disabilities. Participants responded unanimously that technology poses economic issues for disabled people.

Table 4.

Overview of participant perspectives on ethical, social, legal, and economic implications of technology.

Table 5 indicates that participants generally identified more issues posed by neurotechnology for disabled people than people without disabilities. Participants responded unanimously that neurotechnology poses economic issues for disabled people.

Table 5.

Overview of participant perspectives on ethical, social, legal, and economic implications of neurotechnology.

Table 6 outlines the ethic, social, legal, and economic issues posed by technology, including neurotechnology identified by participants including consent (30%), access to technology (60%), socialization (80%), the portrayal of technology in social media (20%), and affordability, disparity, and exclusion (100%).

Table 6.

Overview of themes identified within the perspectives related to the ethic, social, legal, and economic issues posed by technology, including neurotechnology.

3.4.1. Ethical Issues

A total of 30% of participants suggested that ethical issues are linked to the responsible use of technology. For example,

P4: … “ethical issues pertain to ethical use” and the type of activity in which the technology is being used for, for example criminal activity.

A similar sentiment was echoed by another participant:

P9: … “it is not a yes or no thing it is more like if you are using technology responsibly”

A total of 30% suggested that ethical issues are linked to consent and 30% suggested that human enhancement can cause ethical issues including issues with fairness.

P1: … “so if they don’t have a disability and are using like the artificial hippocampus I think it could be like all sorts of different things. Like it is just making like that having superhuman.”

P2: … “you are still adding something to the human body that was not there before that probably have ethical implications, as in is it fair to the others… this person with a disability is getting an advantage on people”

A total of 20% of participants suggested that there are ethical issues related to fairness in general, 10% identified issues related to fairness in education settings, and 10% identified ethical issues related to blind communities.

P7: … “It does pose ethical issues. One strong example I can give is the blind community and society in general because they are like oh there is brail displays so if you have all this technology then brail, paper brail doesn’t matter anymore. It matters big time.”

Ethical issues were also linked to one’s identity; 20% of participants suggested that technological impacts on user identity can cause ethical issues and 10% suggested that technology eliminates human vs human interaction.

P6: … “I think there’s there’s always a question of like, like again I go back to what I had said before in terms of you know where is a person’s identity as a person with a disability start to be infringed upon by technology?”

A similar sentiment was echoed by another participant:

P7: … “if it hampers physical their identify, what they see as their awareness, their physical awareness because people with disabilities if you identify in a certain way, it is no different than a sexual orientation.”

3.4.2. Social Issues

A total of 80% of participants mentioned issues surrounding the impacts of technology on socialization but none mentioned societal impact.

P6: … “Because they can’t communicate in the same ways, technology can make it easier to socialize.

Furthermore, 50% of participants suggested that access is a social problem, 30% suggested specifically that exclusion created by technology is a social problem, and 20% of participants suggested that social problems are created in the media.

P4: … “it has to do with umm their ability to access and afford the technology… it may create a barrier between themselves and their social supports or their friends.”

P9: “you definitely notice when someone is using an assistive device and you notice the gap between the one without one and someone with one and how that neuro like that neuro technology is kind of providing a social divide”

P5: … “Like a lot of the stigma comes from the media because of tragic things that happened and then you find out that someone was mentally ill that was doing it and then people are out raged…”

While 30% of participants suggested that technology creates social problems in deaf culture.

P8: … “So if you are a child that your parent has decided for you that you will have one and then I know that certain people in the Deaf community look at you know the experiences of true deaf folks compared to those who have some hearing through cochlear implants or other interventions.”

3.4.3. Legal Issues

A total of 60% suggested that consent is a legal issue, 50% suggested that problems with access can cause legal issues, 50% suggested that privacy and security are legal issues, 10% suggested that autonomous technology creates legal issues, and 10% of participants suggested legal issues arise because the capabilities of technology are not fully understood.

P9: … “as technology get so more advanced, I guess it is a court battle because it is so new and so, it’s not fully understood what its capable of… I mean also you need to be using it responsibly, but that also goes for the people who are creating it”

P6: … “when we’re talking about people with disabilities, they are more reliant on those technologies right. and you know especially when we talk about let’s say privacy and security... those types of issues… that’s why I say the whole idea of how you know if you are reliant on the technology and having the ability to be secure and private is critical but often we sacrifice things like security and privacy for things like convenience as people without disabilities or people with disabilities as well.”

P4: … “I think there are legal issues in terms of you know if somehow the technology is involved in an accident, then who is involved… If the neurotechnology in some way maybe alters consciousness for example and the person gets into an accident, who’s responsible, who was the cause or what or who was the cause of the accident.”

3.4.4. Economic Issues

All discussed economic issues around affordability, disparity, and exclusion.

P1: … “people that are wealthy would have probably have more advanced, more ability to access to technology so it would create more disparity between the wealthy and the poor.”

P2: … “I think economically, financially people with disabilities, you know are on the poverty line and they cannot afford these technologies that come forth.”

P9: … “And it separates them because if you don’t have this kind of technology then you can’t really function as part of society and it just creates more issues than it solves”

Of the participants, 10% suggested that economic issues can cause social issues.

P9: … “if you can’t afford that then you’re pushed further into poverty um and it does separate people and jobs security is not as secure with technology I feel.”

3.5. Governance of Technology Including Neurotechnology and Governance of Knowledge Production

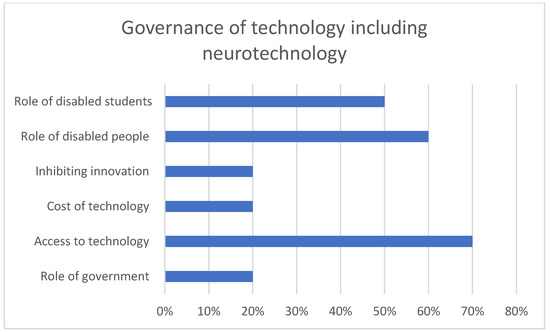

Figure 3 outlines participants’ perspectives on what is needed to be governed in relation to technology including neurotechnology: access to technology (70%), cost of technology (20%) and inhibition of innovation (20%). In total, 60% believed that disabled people and 50% believed that disabled students should be involved in the governance of technology including neurotechnology.

Figure 3.

Overview of themes related to the governance of technology, including neurotechnology.

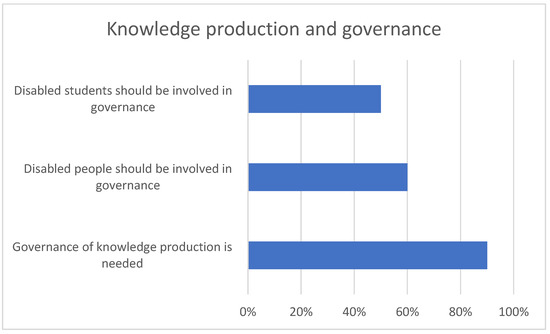

Figure 4 outlines participants’ perspectives on what is needed in the governance of knowledge production whereby 60% argued that disabled people and 50% that disabled students should be involved in knowledge production governance.

Figure 4.

Overview of themes related to knowledge production governance.

3.5.1. Governance of Technology Including Neurotechnology

Role of Government

A total of 20% of participants suggested that government have a role in economic issues.

P6: … “You know when we talk about consistency across the country, you know not all provinces have the same access to technology within you know programs within government funding or some of these other things. So, it is even inconsistent with even what is available, and you know how do you make that available to the rest of the people.”

Access to Technology

Additionally, 70% suggested that access to technology needs to be governed.

P9: … “access to it could be regulated, just so that you’re ensuring that people who do need them are getting them”

Cost of Technology

A total of 20% suggested that cost of technology needs to be governed.

P5: … “the cost of it should be governed because I think the people who need it aren’t necessarily going to be able to afford it.”

Inhibiting Innovation

Likewise, 20% suggested that governance can inhibit innovation.

P6: … “We want to promote innovation. We want to have ideas. We don’t want to stifle those ideas… But at the same time, you want to be careful. You don’t want to have issues come up that you could have prevented … There is a weird balancing act between like innovation and like if you have a great new idea that is going to like cause a lot of social good.”

Role of Disabled People

A total of 60% suggested that disabled people should have a role in the governance of technology.

P2: … “People with disabilities... are the only ones who can say this is how I feel about this … this is how it is working; this is how it is not working… This is what I require in order to be a functioning, stable person… Without them advocating for themselves, engineers or not anybody wouldn’t know what gaps there are to fill… So, their input is very imperative to understanding technology and governance…”

Role of Disabled Students

A total of 50% suggested that disabled students should have a role in the governance of technology.

P9: … “Absolutely, um their voice it matters to the population you are trying to target, and you need to hear from the population… I really believe the people with disabilities are the people that you need to be consulting regularly and the people who have knowledge in the disability field.”

P8: … “Absolutely, I think that is where innovation happens. I think students are younger and more creative. And they have had access to technology growing up and it I mean it is exciting what students can come up with and particularly students with disabilities who are in this field of study are just such an asset.”

3.5.2. Intersection of Knowledge Production and Governance

All commented on the role of governance of neurotechnology knowledge production and how it impacts disabled people. A total of 90% indicated that there is a need for governance and 60% suggest that disabled people ought to be involved and 50% suggested that disabled students ought to be involved.

P4: … “There should be a policy in place that both able-bodied and disabled people need to be involved in the design.”

P5: … “I think disability, people with disabilities should play a role in governing and um kind of fixing the problems with it… Like problems with technology and society’s viewpoints.”

P8: … “you can’t develop policy unless you are actually bringing people who are impacted by that policy to the physical table and discussion.”

Only 10% stated that governance of knowledge production is not needed.

4. Discussion

According to participants, the narrative undergraduate disabled students are exposed to does not prompt them to think of themselves as potential researchers, and undergraduate disabled students face numerous barriers in becoming knowledge producers. Our participants lacked exposure to science and technology especially around the ethical, legal, and social implications of technology, although they all felt that technology has such implications. Participants furthermore felt that undergraduate disabled students have a role to play in the governance of science and technology. In the remainder of this section, we discuss our findings through the lens of the importance of roles and identity, the career development of students, and science and technology governance.

4.1. Researcher Identity and Role of Disabled Students

It is argued that students [7,41,42,43,44,45], including undergraduate students [17] can and should identify and occupy the role of researcher or knowledge producer due to its many benefits [7,46,47,48,49,50]. Disabled students are part of the student cohort. All 10 participants stated that anyone can be a knowledge producer and discussed the importance of both academic and community-based knowledge production. However, despite their enthusiasm towards knowledge production, only 20% had undergraduate research experience beyond course-based work. The question is why is there such a disconnect? Opportunities to become engaged in knowledge production are paramount to developing a research identity [17]. A total of 60% stated that their disability impacts their post-secondary choices, and 100% outlined barriers they have experienced that curtail their ability to develop a research identity such as physical barriers (i.e., lack of access to facilities and transportation), attitudinal barriers (i.e., feeling overlooked, lack of mentors, lack of willingness to be accommodated), lack of exposure to a research identity, and lack of opportunity to engage in research. As Participant 4 stated, “I think one of the barriers that I have experienced just as a student and just as a woman with a disability is that there hasn’t been a lot of opportunities to take part in research”. The lack of opportunities and barriers experienced fits with barriers disabled students experience in universities in general [19,56,69,111]; for example, attitudinal barriers experienced by 60% of participants is a problem described for disabled students in general [111,112,113,114,115,116] but also for disabled academics [117,118,119]. Participant 6 stated, “It can be an attitudinal barrier can maybe be a big problem in terms of being able to be engaged in knowledge production particularly if you are in an environment that you don’t feel valued.” Developing a research identity is noted as empowering for undergraduate students [17] and role theory suggests that expectations of oneself are influenced by the role expectations by others [38]. However, feeling overlooked and disempowered are often feelings expressed by disabled students [57], and was a theme identified in this study. Participant 9 echoed this sentiment, “I think that students with disabilities are a population that are overlooked sometimes.” Undergraduate disabled students are well positioned to become researchers and be instrumental in filling the knowledge gaps that are known to exist and to bring invisible voices to the research agendas. The lack of mentorship our participants identified as a barrier reflects existing literature which often highlights mentorship as an important aspect of the research experience of undergraduate students [120,121], including underrepresented groups [122,123]. Given that identity is a “source of motivation for action particularly actions that result in the social confirmation of the identity” [124] (p. 242), our findings suggest that the climate is not such that undergraduate disabled students will take up the researcher role. Various academic studies investigated the motivation of students and faculty [125,126,127,128,129]. Our data suggest that the experience of our participants would lead to a low intrinsic motivation, which has as one parameter the ability to succeed [127,129]. A study by Daumiller et al., about “Motivation of higher education faculty” [125] outlines in Figure 1 on page 4 an overview model of faculty motivation and describes many factors that might motivate (e.g., feasible, desirable), or demotivate (e.g., receiving rejection) faculty covering many different forms of motivation and theories such as self-determination theory, achievement goal theory, control value theory, and social cognitive career theory. What our participants describe would mostly be seen as decreasing their motivation as most of the motivators seem not to be there, such as relatedness and many other indicators. Although the studies [125,126,127,128,129] did not look at disabled faculty or disabled students, many of the demotivators and motivators identified do apply to disabled students and faculty. Given the many studies that suggest that disabled students feel stigmatized due to the negative narrative around ‘disability’ [19] a reality also seen to apply to disabled faculty [130,131] and given the many other problems for disabled students, academic and non-academic staff described in the literature [24], the sentiments voiced by our participants fits with the reality described in other studies. Indeed, our participants stated clearly that disabled people and students should be knowledge producers but that they felt discouraged. Given that the problems they experience do not disappear when they reach the faculty level, this might discourage them to continue the academic research trajectory. Being discouraged to continue towards a research career might be more severe for disabled students where the motivation for an academic career is linked to a research agenda that focuses on the social situation of disabled people than for disabled students who want to perform medical research linked to ‘disability’ or where research is not linked to ‘disability’ at all. However, there are many other issues disabled faculties face such as harassment and unfair treatment [132] that might demotivate undergraduate disabled students to pursue academic careers.

Given the well-described utility for undergraduate students of being researchers [18] such as in relation to career choices [52,55] and providing students with skills needed to prepare students for an ever more complex society [133], it is problematic that undergraduate disabled students are not engaged in research. Although initiatives are underway in Canada aimed to increase the numbers of disabled academic faculty members [25,26,27] many problems exist [18,24] and such efforts are futile unless a researcher identity is developed within undergraduate disabled students and even earlier such as high school as noted in the case of women in STEM [45,134]. As Participant 2 stated, “In order for someone to take [the student] on as a researcher, usually students that start as a researcher did it in high school or has a sibling who can connect them.” Therein, we suggest that efforts are needed to engage students in developing a research identity earlier on and that engagement with barriers in relation to a research identity is necessary.

4.1.1. Researcher Identity and Choosing a Topic

The dynamics of how a research topic is chosen is not covered in the literature in relation to disabled students and disabled academics in general [18,24]. This is problematic given that this was for 80% of our participants an essential factor for getting involved in research and that 80% wanted to work on disability topics. Indeed, for our participants, the research topic was a main motivator. Choosing a topic is noted as a problem for other underrepresented groups stating that one often has to go in one’s choice against the reality that certain knowledge, evidence, research questions and methods are privileged [123]. It is also noted that there is a bias in how disabled people are engaged with in academic inquiries, namely that evidence on social problems disabled people experience is missing in relation to science and technology [34,35,135] and also beyond [4,5,6,136]. Fear of repercussions from sharing one’s lived experience mentioned by two participants is a valid concern given that 35% of disabled Canadian University professors, instructors, teachers, or researchers “experienced unfair treatment or discrimination” and 47% experienced harassment [132] and this fits with the issue flagged around the unwillingness of disabled academics to identify themselves as a disabled person [130,131].

4.1.2. Researcher Identity and Advocacy

Disabled people are experts of their situation [4,15,16], and this was a common theme within participant responses. Participant 8 stated, “because of our lived experience, we are experts… we are the experts and the knowledge producers of our own experience”. Disabled people have an important role to play in research [137,138], and disability-related research can also be translated into evidence-based advocacy [139]. Ninety percent of participants indicated that they want to perform research on disability-related issues. Participant 4 stated, “I think it is important to be engaged in research opportunities particularly those that affect the disability community.” On the participants, twenty percent indicated that they want to perform research on non-disability-related issues, while 30% identified community-based research as an opportunity to advocate for people with disabilities. Participant 2 stated, “People with disabilities can only advocate for people with disabilities…Without them advocating for themselves, engineers or not anybody wouldn’t know what gaps there are to fill”.

Eighty percent of participants highlighted that academic knowledge production provides the foundation for policy and decision-making and two that it provides the foundation for community change. All also believed that the role of community-based knowledge production, which fits with the literature around participatory action research, citizen sciences and community being the scholar, whereby the case is made that being a researcher and developing the identity of being a researcher as an undergraduate is enticing a student to learn about research methods and also think about being a researcher in their community job after graduation [7,89]. Forty percent highlighted problems with knowledge production such as disabled people being ignored and biases. This fits with the recognized problem of for example missing data on the social situations of disabled people [5] including in the academic situation around equity, diversity, and inclusion [24].

4.2. Knowledge Production and Science and Technology Governance

Science and technology-focused knowledge production and knowledge production for science and technology including governance is seen as a political and social process [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,29]. The interaction “between scientific and citizen groups [is seen] to be a crucial element of the modern ways of knowledge production and governance” [31]. Disabled people are often the anticipated users of technology including neurotechnology [33,37] and are impacted by how the changes in social parameters caused by the use of science and technology including neurotechnology are governed. Therefore, disabled people have a stake in how science and technology including neurotechnology are advanced and governed [29,34,140].

Our results indicate that many undergraduate disabled students are not exposed in universities to discussions focusing on the ethical, legal, and social implications surrounding technology including neurotechnology. At the same time, all 10 participants felt that there are implications linked to advancements in science and technology including neurotechnology. This gap in the training is problematic and should be filled.

All participants were interested in technology including neurotechnology, but only two of these participants were involved in knowledge production related to technology, which is problematic. Participant 9 stated, “I really believe the people with disabilities are the people that you need to be consulting regularly and the people who have knowledge in the disability field.” All participants felt that there are implications linked to advancements in science and technology including neurotechnology and stated that there are negative and positive impacts of technology including neurotechnology. One hundred percent of participants generated ethical, legal, and economic examples for technology (16 examples) including neurotechnology (14 examples). Furthermore, 90% of participants indicated that there is a need for governance, 60% suggested that disabled people ought to be involved, and 50% suggested that disabled students ought to be involved. These findings suggest that changes in how universities deal with undergraduate disabled students as knowledge producers including researchers are warranted. The lived experiences and academic background of undergraduate disabled students put them in an advantageous position to produce knowledge on technology, including neurotechnology, and their governance from the point of view of disabled people. For example, participant 8 stated, “I think that is where innovation happens. I think students are younger and more creative. And they have had access to technology growing up and it, I mean it is exciting what students can come up with and particularly students with disabilities who are in this field of study are just such an asset.”

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest the need for change in how research is taught to disabled students at the undergraduate and high school student level, for more opportunities for undergraduate and high school disabled students to be involved in knowledge production, such as research, and a solid exposure to and support in developing a research identity for undergraduate and high school disabled students. Our findings can inform fields such as science and technology studies, STEM education, disability studies, and topics such as “Equity/Equality, Diversity and Inclusion” (EDI).

Undergraduate disabled students could provide valuable perspectives regarding the ethical, social, legal, and economic issues surrounding scientific and technological advancements including neuro-based scientific and technological advancements, robotics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning, given their lived experienced as disabled people who are constantly impacted by advancements in science and technology. Indeed, 100% of participants stated that undergraduate disabled students should be involved in knowledge production that influences science and technology including neurotechnology governance, although not one of the participants were involved. Undergraduate disabled students must be explicitly exposed early in their academic career to the existing science and technology governance discourses so they can make a linkage between their own situation and what is discussed in these discourses with the hope that some will be enticed to pursue research projects covering the social implications of advancements in science and technology and enriching these discourses with data missing in relation to disabled people.

Our findings indicate that further studies on knowledge production by disabled students are needed. Studies that interview people involved in university and community-based research and knowledge production and policy-makers may be warranted. One could interview disabled high school students and disabled university students, not part of our sample such as deaf students, to generate qualitative data on their perspectives on the development of a research identity and their role in research-based knowledge production. More studies are needed to be able to develop in-depth best practices regarding how to increase the number of undergraduate disabled student researchers. Studies are especially needed to investigate in depth the issue of choosing a research topic. More studies are also needed on equity, diversity, and inclusion policy actions in relation to disabled people.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.W. and A.L.; methodology, A.L. and G.W.; formal analysis, A.L. and G.W.; investigation, A.L. and G.W.; data curation A.L. and G.W.; writing—original draft preparation A.L.; writing—review and editing, G.W. and A.L.; supervision, G.W.; project administration, G.W.; funding acquisition, G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Government of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction ERN 155204 in cooperation with ERA-NET NEURON JTC 2017.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved on 23 February 2018 by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, University of Calgary (REB17-0785).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants for giving us their precious time.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hessels, L.K.; Van Lente, H. Re-thinking new knowledge production: A literature review and a research agenda. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 740–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.; Nylén, L.; Thielen, K.; van Der Wel, K.A.; Chen, W.-H.; Barr, B.; Burström, B.; Diderichsen, F.; Andersen, P.K.; Dahl, E.; et al. How Do Macro-Level Contexts and Policies Affect the Employment Chances of Chronically Ill and Disabled People? Part II: The Impact of Active and Passive Labor Market Policies. Int. J. Health Serv. 2011, 41, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chataika, T.; McKenzie, J.A. Global institutions and their engagement with disability mainstreaming in the south: Development and (dis) connections. In Disability in the Global South. International Perspectives on Social Policy, Administration, and Practice; Grech, S., Soldatic, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 423–436. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Disability. Available online: http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en/index.html (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Berghs, M.; Atkin, K.; Graham, H.; Hatton, C.; Thomas, C. Implications for Public Health Research of Models and Theories of Disability: A Scoping Study and Evidence Synthesis. Available online: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/103434/1/FullReport_phr04080.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Wolbring, G.; Djebrouni, M.; Johnson, M.; Diep, L.; Guzman, G. The Utility of the “Community Scholar” Identity from the Perspective of Students from one Community Rehabilitation and Disability Studies Program. Interdiscip. Perspect. Equal. Divers. 2018, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, S.; Turner, J.H. What makes a science’mature’?: Patterns of organizational control in scientific production. Soc. Theory 1986, 4, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, K.; Cushing, L.; Wesner, A. Science Shops and the US Research University: A Path for Community-Engaged Scholarship and Disruption of the Power Dynamics of Knowledge Production. In Educating for Citizenship and Social Justice; Mitchell, T., Soria, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, S. Democratizing science movements: A new framework for mobilization and contestation. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2007, 37, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, G.; Yanacopulos, H. Governing and democratising technology for development: Bridging theory and practice. Sci. Public Policy 2007, 34, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, J.; D’Silva, J. Knowledge transfer from citizens’ panels to regulatory bodies in the domain of nano-enabled medical applications. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2009, 22, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guston, D. Understanding ‘anticipatory governance’. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2014, 44, 218–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suhay, E.; Druckman, J.N. The Politics of Science: Political Values and the Production, Communication, and Reception of Scientific Knowledge Introduction. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2015, 658, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Disability Action Plan 2014–2021. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/199544/1/9789241509619_eng.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Hamraie, A.; Fritsch, K. Crip Technoscience Manifesto. Catal. Fem. Theory Technosci. 2019, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seymour, E.; Hunter, A.B.; Laursen, S.L.; Deantoni, T. Establishing the benefits of research experiences for undergraduates in the sciences: First findings from a three-year study. Sci. Educ. 2004, 88, 493–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lillywhite, A.; Wolbring, G. Undergraduate disabled students as knowledge producers including researchers: A missed topic in academic literature. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hutcheon, E.J.; Wolbring, G. Voices of “disabled” post secondary students: Examining higher education “disability” policy using an ableism lens. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2012, 5, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podemski, R.S.; Marsh, G.E. A Systems Framework for Assessing Attitudes toward the Learning Disabled. Learn. Disabil. Q. 1981, 4, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, F.J. The Road to the Ivory Tower: The Learning Experiences of Students with Disabilities at the University of Manitoba. Qual. Res. Educ. 2015, 4, 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pasay-An, E.A. Echoes of silence: The unheard struggles of the physically impaired learners in the mainstream education. Philipp. J. Nurs. 2015, 85, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, A. The right to education: What is happening for disabled students in New Zealand? Disabil. Stud. Q. 2016, 36, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G.; Lillywhite, A. Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) in Universities: The Case of Disabled People. Societies 2021, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. 2019 Made-in-Canada Athena SWAN Consultations. Available online: http://www.nserc-crsng.gc.ca/Forms-formulaires/Swan-2019_eng.asp (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Government of Canada. Canada Research Chairs Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Requirements and Practices. Available online: http://www.chairs-chaires.gc.ca/program-programme/equity-equite/index-eng.aspx (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Government of Canada. Advisory Committee on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Policy. Available online: http://www.chairs-chaires.gc.ca/program-programme/equity-equite/advisory_committee_on_equity-eng.aspx (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Biddle, B.J. Recent Developments in Role Theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1986, 12, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, H.; Winickoff, D. Issues in Neurotechnology Governance. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/c3256cc6-en (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Gerritsen, A.L.; Stuiver, M.; Termeer, C.J. Knowledge governance: An exploration of principles, impact, and barriers. Sci. Public Policy 2013, 40, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouper, I. Science blogs and public engagement with science: Practices, challenges, and opportunities. J. Sci. Commun. 2010, 9, A02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Micera, S.; Caleo, M.; Chisari, C.; Hummel, F.C.; Pedrocchi, A. Advanced Neurotechnologies for the Restoration of Motor Function. Neuron 2020, 105, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Launch of the First WHO Priority Assistive Products List. Available online: http://www.who.int/phi/implementation/assistive_technology/en/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Lillywhite, A.; Wolbring, G. Coverage of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning within Academic Literature, Canadian Newspapers, and Twitter Tweets: The Case of Disabled People. Societies 2020, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yumakulov, S.; Yergens, D.; Wolbring, G. Imagery of Disabled People within Social Robotics Research. In Social Robotics; Ge, S., Khatib, O., Cabibihan, J.-J., Simmons, R., Williams, M.-A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7621, pp. 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G.; Diep, L. Cognitive/Neuroenhancement through an Ability Studies lens. In Cognitive Enhancement; Jotterand, F., Dubljevic, V., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria, R.; Lillywhite, A.; Villamil, V.; Wolbring, G. How research literature and media cover the role and image of disabled people in relation to artificial intelligence and neuro-research. Eubios J. Asian Int. Bioeth. (EJAIB) 2019, 29, 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, H.M. Reference group influence in consumer role rehearsal narratives. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2015, 18, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Cho, E. The culturally situated process of knowledge production in a virtual community: A case of hypertext analysis from a university’s class web discussion boards. Curr. Issues Comp. Educ. 2003, 6, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.C.; Hung, D.; Scardamalia, M. Education in the knowledge age—Engaging learners through knowledge building. In Engaged Learning with Emerging Technologies; Hung, D., Khine, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, P.; Gunter, H. From ‘consulting pupils’ to ‘pupils as researchers’: A situated case narrative. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2006, 32, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholtz, M.; Lopez, A.; Mojarro, A.; Skapoulli, E.; VanderStouwe, C.; Warner-Garcia, S.J.L.; Compass, L. Sociolinguistic justice in the schools: Student researchers as linguistic experts. Lang. Linguist. Compass 2014, 8, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, K.T. Creating ICT-enriched learner-centred environments: Myths, gaps and challenges. In Engaged Learning with Emerging Technologies; Hung, D., Khine, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kerfeld, C.A.; Simons, R.W. The undergraduate genomics research initiative. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunter, J.; O’Brien, L. How do high school students create knowledge about improving and changing their school? A student voice co-inquiry using digital technologies. Int. J. Stud. Voice 2018, 3, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Saddler, T.N. Socialization to Research: A Qualitative Exploration of the Role of Collaborative Research Experiences in Preparing Doctoral Students for Faculty Careers in Education and Engineering. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/27615/SaddlerETD.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Adedokun, O.A.; Zhang, D.; Parker, L.C.; Bessenbacher, A.; Childress, A.; Burgess, W.D. Understanding how undergraduate research experiences influence student aspirations for research careers and graduate education. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 2012, 42, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- McGinn, M.K.; Lovering, M. Researcher Education in the Social Sciences: Canadian Perspectives about Research Skill Development. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid=B46E8A2178040289B062FC5DCCDC5DD9?doi=10.1.1.548.9879&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Purdy, J.P.; Walker, J.R. Liminal Spaces and Research Identity The Construction of Introductory Composition Students as Researchers. Pedagogy 2013, 13, 9–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; Nettell, R.; Furukawa, G.; Sakoda, K. Education. Beyond contrastive analysis and codeswitching: Student documentary filmmaking as a challenge to linguicism in Hawai‘i. Linguist. Educ. 2012, 23, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.N.; Wagner, S.E. Research Motivations and Undergraduate Researchers’ Disciplinary Identity. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Social cognitive career theory. In Career Choice and Development; Duane, B., Ed.; Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 255–311. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, J.P. Influences on the career development of gay men. Career Dev. Q. 1995, 44, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Fouad, N.A.; Smith, P.L. Asian Americans’ career choices: A path model to examine factors influencing their career choices. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gushue, G.V.; Scanlan, K.R.; Pantzer, K.M.; Clarke, C.P. The relationship of career decision-making self-efficacy, vocational identity, and career exploration behavior in African American high school students. J. Career Dev. 2006, 33, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G. Special Educational Needs and Disabilities in Higher Education (Canada). Bloomsbury Educ. Child. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, S. From Policy to Practice in Higher Education: The experiences of disabled students in Norway. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2011, 58, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.M.; Pattison, E.; Muller, C.; Sutton, A. Barriers to Bachelor’s Degree Completion among College Students with a Disability. Sociol. Perspect. 2020, 63, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.M.; Stransky, O.; Negron, R.; Bowlby, M.; Lickiss, J.; Dutt, D.; Dasgupta, N.; Barbosa, P. Institutional Barriers to Diversity Change Work in Higher Education. SAGE Open 2013, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacklin, A.; Robinson, C.; O’Meara, L.; Harris, A. Improving the Experiences of Disabled Students in Higher Education. Available online: http://cascadeoer2.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/33757279/jacklin.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Holloway, S. The experience of higher education from the perspective of disabled students. Disabil. Soc. 2001, 16, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J. Negotiating identities, negotiating environments: An interpretation of the experiences of students with disabilities. Disabil. Soc. 1996, 11, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.B.; Hilton, M.L.; Dibner, K.A. Indicators for Monitoring Undergraduate STEM Education; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, S.; Scevak, J.; Southgate, E.; Buchanan, R. Non-Disclosing Students with Disabilities or Learning Challenges: Characteristics and Size of a Hidden Population. Aust. Educ. Res. 2017, 44, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, T.S.; Kreiser, N.; Camargo, E.; Grubbs, M.E.; Kim, E.J.; Burge, P.L.; Culver, S.M. STEM Faculty Experiences with Students with Disabilities at a Land Grant Institution. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2015, 3, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, J. Early interest in STEM and career development: An analysis of persistence in students with disabilities. J. Educ. Res. Policy Stud. 2013, 13, 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Burgstahler, S.; Crawford, L. Managing an E-Mentoring Community to Support Students with Disabilities: A Case Study. AACE J. 2007, 15, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M.; Hopson, R.K. Advancing Evaluation of STEM Efforts through Attention to Diversity and Culture. New Dir. Eval. 2006, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Barnar-Brak, L.; Lectenberger, D.; Lan, W.Y. Accommodation strategies of college students with disabilities. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olney, M.F.; Kim, A. Beyond adjustment: Integration of cognitive disability into identity. Disabil. Soc. 2001, 16, 563–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, R.J.; Hampton, J.L. Science and engineering as viable career choices for students with disabilities: A survey of parents and teachers. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2000, 43, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. Students with Disabilities Choosing Science Technology Engineering and Math (STEM) Majors in Postsecondary Institutions. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2014, 27, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, A.R.; Fairweather, J.S. The role of postsecondary education in the path from high school to work for youth with disabilities. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 2012, 55, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]