Lecturer Competence from the Perspective of Undergraduate Psychology Students: A Qualitative Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. European Higher Education Area and the Issue of Evaluation

1.2. Students’ Perceptions of Lecturer Competence

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials and Procedures

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mulder, M.; Gulikers, J.; Biemans, H.; Wesselink, R. The new competence concept in higher education: Error or enrichment? J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2009, 33, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinchero, R. Costruire, Valutare, Certificare Competenze. Proposte Di Attività per La Scuola; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Westera, W. Competences in education: A confusion of tongues. J. Curric. Stud. 2001, 33, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Valcárcel, A. Características del “buen professor” universitario segúne studiantes y profesores universitario [The “good professor” characteristics according to students and teachers]. Rev. Investig. Educ. 1992, 10, 31–50. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=764529 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Pascual, I.Y.; Gaviria, J.L. El problema de la Fiabilida den la Evaluación de la eficiencia docenteen la universidad: Una alternative metodológica [The problem of reliability in the evaluation of teaching efficiency at the university: A methodological alternative]. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2004, 229, 359–376. Available online: https://revistadepedagogia.org (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Alweshahi, Y.; Harley, D.; Cook, D.A. Students’ perception of the characteristics of effective bedside teachers. Med. Teach. 2007, 29, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartram, B.; Bailey, C. Different students, same difference? A comparison of UK and international students’ understandings of ‘effective teaching’. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2009, 10, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, L.; McAndrew, M.; Muzaffar, A.; Mucciolo, T.W. Characteristics of effective clinical teachers identified by dental students: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2013, 17, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, B. What is ‘good teaching’ in engineering education in India? A case study. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2004, 41, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabalín, D.; Navarro, N. Conceptualización de los estudiant essobreel buen profesor universitario en las carreras de la salud de la Universidad de La Frontera-Chile. Int. J. Morphol. 2010, 26, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero Martinez, A. ¿Cómo es el buen profesor universitario segúne la lumnado? Rev. Española Pedagog. 2010, 68, 223–242. Available online: https://https://www.jstor.org/stable/23766298 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Parpala, A.; Lindblom-Ylänne, S.; Rytkönen, H. Students’ conceptions of good teaching in three different disciplines. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2011, 36, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.; del Mar, M.; García, B.; Quintanal, J. El perfil del professor universitario de calidad desde la perspectiva del alumnado [The profile of a quality university professor from the student’s perspective]. Educación 2006, 9, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Di Battista, S.; Pivetti, M.; Berti, C. Competence and benevolence as dimensions of trust: Lecturers’ trustworthiness in the words of Italian students. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabaleta, F. The use and misuse of student evaluations of teaching. Teach. High. Educ. 2007, 12, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, C.; Fröhlich, M.; Gehrke, E.; Isoski, T. Bologna with Student Eyes. 2015. Time to Meet the Expectations from 1999. European Students’ Union. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED578176.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Yáñez, O.J.; Orsini Sánchez, C.; Hasbún Held, B. Atributos de una docencia de calidad en la educación superior: Una revision sistemática [Attributes of quality teaching in higher education: A systematic review]. Estud. Pedagógicos 2016, 3, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, M.; Martinez, R.; Troyanor, Y.; Teruel, P. Student perspectives on the university professor role. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2011, 39, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friz, M.; Sanhueza, S.; FigueroaManzi, E. Concepciones de los estudiantes para professor de matemáticas sobre las competencias professional es implicada sen la ensenanza de la estadística [Pre-Service Mathematics Teachers’ Concepts Regarding the Professional Competencies Involved in the Teaching of Statistics]. Rev. Electron. Investig. Educ. 2011, 13, 113–131. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1607-40412011000200008 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Glenn, D.; Patel, F.; Kutieleh, S.; Robbins, J.; Smigiel, H.; Wilson, A. Perceptions of optimal conditions for teaching and learning: A case study from Flinders University. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2012, 31, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basow, S.A.; Phelan, J.E.; Capotosto, L. Gender patterns in college students’ choices of their best and worst professors. Psychol. Women Q. 2006, 30, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.; Leung, A.; Dunne, S. So how do you see our teaching? Some observations received from past and present students at the Maurice Wohl Dental Centre. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2012, 16, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Merellano, E.; Almonacid-Fierro, A.; Moreno-Doña, A.; Castro-Jaque, C. Buenos Docentes universitarios: Quédicen Los, Estudiantes? [Good University Teachers: What Do Students Say about Them?]. Available online: https://repositorio.uautonoma.cl/handle/20.500.12728/5317 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Ramsden, P. Learning to Teach in Higher Education, 2nd ed.; Routledge Falmer: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt, J. The power of teaching–learning environments to influence student learning. In Student Learning and University Teaching; Entwistle, N.J., Tomlinson, P.D., Eds.; British Psychological Society: London, UK, 2007; pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Barrie, S.C.; Ginns, P.; Prosser, M. Early impact and outcomes of institutionally aligned, student focused learning perspective on teaching quality assurance. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2005, 30, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradellini, C.; Gómez-Cantarino, S.; Dominguez-Isabel, P.; Molina-Gallego, B.; Mecugni, D.; Ugarte-Gurrutxaga, M.I. Cultural Competence and Cultural Sensitivity Education in University Nursing Courses. A Scoping Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 682920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascolo, M.F. Beyond student-centered and teacher-centered pedagogy: Teaching and learning as guided participation. Pedagog. Hum. Sci. 2009, 1, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sharan, S.; Shaulov, A. Cooperative learning, motivation to learn, and academic achievement. In Cooperative Learning: Theory and Research; Sharan, S., Ed.; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 173–202. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, A. Le réseau d’associations. In Méthodesd’étude Des Représentations Sociales; Abric, J.-C., Ed.; Érès: Ramonville Saint-Agne, France, 2003; pp. 81–117. [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps, J.C. Analyse des correspondances et variations des contenus de représentations sociales. In Méthodes d’étudedes représentations sociales; Abric, J.-C., Ed.; Érès: Ramonville Saint-Agne, France, 2003; pp. 179–199. [Google Scholar]

- Pivetti, M.; Melotti, G.; Bonomo, M. An exploration of social representations of the Roma woman in Italy and Brazil: Psychosocial anchoring to emotional reactions. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2017, 58, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebart, L.; Salem, A.; Berry, L. Exploring Textual Data; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Doise, W.; Clemence, A.; Lorenzi-Cioldi, F. Représentations Sociales Et Analyses de Données [Social Representations and Data Analysis]; PUG (Presses Universitaires de Grenoble): Grenoble, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bertaut, M.B.; de Soto, L.R.G. Textual data analysis computer system SPAD-T. Application example to post-war Spanish press. In Applied Stochastic Models and Data Analysis, Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on ASMDA 1991, Granada, Spain, 23–26 April 1991; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 1991; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Bonomo, M.; Melotti, G.; Pivetti, M. Social Representations of the gypsy woman among non-gypsy Brazilian and Italian population: Psychological and social anchoring. Psicol. Teor. E Pesqui. 2017, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bales, R.F.; Slater, P.E. Role differentiation in small decision-making groups. In Family Socialization and Interaction Process; Parsons, T., Robert Freed, B., Eds.; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1995; pp. 259–306. [Google Scholar]

- RogerRees, C.; Segal, M.W. Role differentiation in groups: The relationship between instrumental and expressive leadership. Small Group Behav. 1984, 15, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M. Reassessing pedagogy in a fast forward age. Int. J. Learn. 2007, 13, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, P.R. Role differentiation in small groups. Amer. Soc. Rev. 1955, 20, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelditch, M., Jr. Role differentiation in the nuclear family. In Family: Socialization and Interaction Process; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1955; pp. 307–351. [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni, A. Dual leadership in complex organizations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1965, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughead, T.M.; Hardy, J.; Eys, M.A. The nature of athlete leadership. J. Sport Behav. 2006, 29, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G.H. Role differentiation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1972, 37, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeker, B.F.; Weitzel-O’Neill, P.A. Sex roles and interpersonal behavior in task-oriented groups. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1977, 42, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, C.S.; Fiore, S.M.; Salas, E. The Role of Shared Cognition in Enabling Shared Leadership and Team Adaptability. In Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership; Pearce, C.L., Conger, J.A., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Solansky, S. Leadership Style and Team Processes in Self-Managed Teams. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 14, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondi, S.; Pivetti, M.; Di Battista, S.; Sarrica, M. What do we expect from robots? Social representations, attitudes and evaluations of robots in daily life. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Mayorga-Fernández, M.; Bravo-Agapito, J.; Escribano-Ortiz, D. Analysis of teachers’ pedagogical digital competence: Identification of factors predicting their acquisition. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2021, 26, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Mayorga-Fernández, M.J. Prediction of factors that affect the knowledge and use higher education professors from Spain make of ICT resources to teach, evaluate and research: A study with research methods in educational technology. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.S. Trust, behavior, and high school outcomes. J. Educ. Adm. 2015, 53, 215–236. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1055550 (accessed on 15 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M. Trust Matters: Leadership for Successful Schools; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tschannen-Moran, M. Fostering teacher professionalism in schools: The role of leadership orientation and trust. Educ. Adm. Q. 2009, 45, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, W.K. A multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning, and measurement of trust. Rev. Educ. Res. 2000, 70, 547–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.C.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Words/Categories | Frequency | Words/Categories | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available | 50 | Strict | 9 |

| Skilful | 43 | Serious | 8 |

| Empathetic | 28 | Respectful | 7 |

| Clear | 26 | Professional | 6 |

| Well-read | 25 | Sociable | 6 |

| Captivating | 24 | Fair | 6 |

| Good-Explanation | 19 | Concise | 6 |

| Meticulous | 18 | Kind | 5 |

| Motivated | 16 | Practical | 5 |

| Charismatic | 15 | Participative | 5 |

| Up-to-date | 11 | Open | 4 |

| Interdisciplinary-knowledge | 9 | Nice | 4 |

| Interactive | 9 | Impartial | 4 |

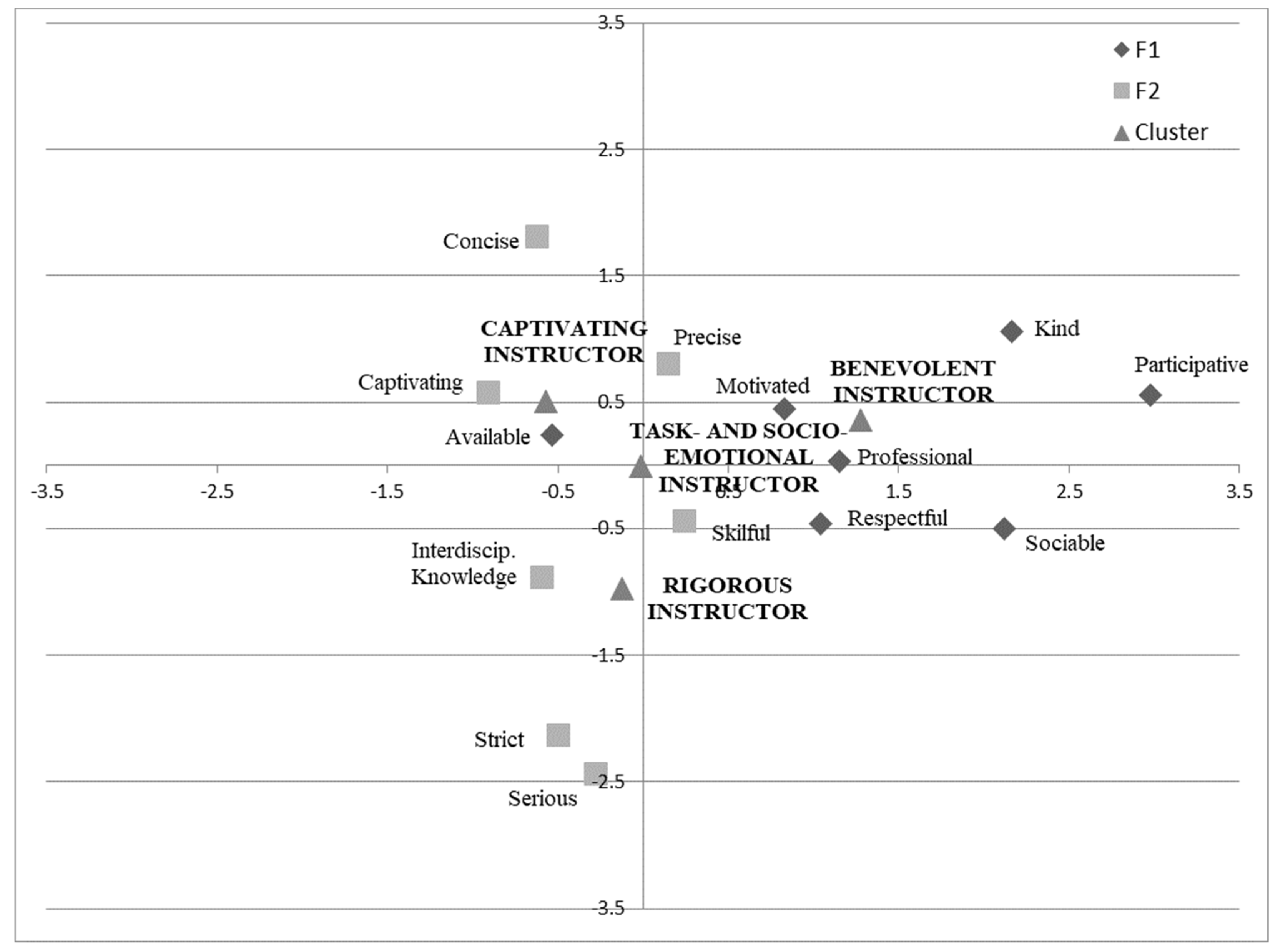

| Cluster 1— “Captivating” Lecturer | Cluster 2— Lecturer Oriented to Both Task and Socio-Emotional Aspects | Cluster 3— Rigorous Lecturer | Cluster 4— Benevolent Lecturer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | V-Test | Categories | V-Test | Categories | V-Test | Categories | V-Test |

| Captivating | 5.5 | Skilful | 2.6 | Strict | 5.0 | Kind | 3.8 |

| Practical | 2.9 | Empathetic | 2.6 | Serious | 3.8 | Participative | 3.8 |

| Open | 2.5 | Clear | 2.5 | Well-read | 3.1 | Impartial | 3.3 |

| Nice | 2.5 | Interactive | 2.2 | Interdisciplinary Knowledge | 2.1 | Professional | 2.6 |

| Concise | 2.4 | Up-to-date | 2.2 | Respectful | 2.3 | ||

| Available | 2.3 | Fair | 2.0 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Battista, S.; Pivetti, M.; Melotti, G.; Berti, C. Lecturer Competence from the Perspective of Undergraduate Psychology Students: A Qualitative Pilot Study. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020139

Di Battista S, Pivetti M, Melotti G, Berti C. Lecturer Competence from the Perspective of Undergraduate Psychology Students: A Qualitative Pilot Study. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(2):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020139

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Battista, Silvia, Monica Pivetti, Giannino Melotti, and Chiara Berti. 2022. "Lecturer Competence from the Perspective of Undergraduate Psychology Students: A Qualitative Pilot Study" Education Sciences 12, no. 2: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020139

APA StyleDi Battista, S., Pivetti, M., Melotti, G., & Berti, C. (2022). Lecturer Competence from the Perspective of Undergraduate Psychology Students: A Qualitative Pilot Study. Education Sciences, 12(2), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020139