1. Introduction

Higher education governance boards are a collective set of individuals who, alongside the faculty and university president (or chancellor), are responsible for carrying out the mission and vision of their respective campuses [

1,

2]. Otherwise known as shared governance, this responsibility for governance boards often includes a fiduciary role in maintaining, growing, and/or recovering the financial health of their college or university [

3]. Board decisions range from determining vendors for university contracts to approving or rejecting tenure and promotion recommendations for faculty, as well as countless other policies that impact the day-to-day operations of university life amongst students, staff, faculty, and administrators.

With this power and decision-making, boards both reflect and shape the institutional priorities of colleges and universities, including efforts with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) [

2]. Colleges and universities have attempted and need to continue to address the long-standing racism, anti-Blackness, and settler-colonialism entrenched within their respective campuses, which includes but is not limited to the intimate involvement in slave economies in building U.S. colleges and universities, the systematic barring of admissions of Black Americans through the racialized utilization of the G.I. Bill, and the excavation on indigenous bodies for “medical purposes” [

4]. Boards can play a pivotal and critical role in institutionalizing this racism through determining what to acknowledge, rectify, and prioritize. The focus of DEI efforts has predominantly centered on the role of students, with growing literature focusing on the roles of faculty and campus leaders such as senior administrators. Yet, as a growing body of research indicates, governance boards play a crucial role in how universities frame and address their responses regarding campus racism, such as in determining whether to change the controversial names of historical landmarks [

5]. Boards either constrain, support, or advance equity-oriented agendas through their policies and actions.

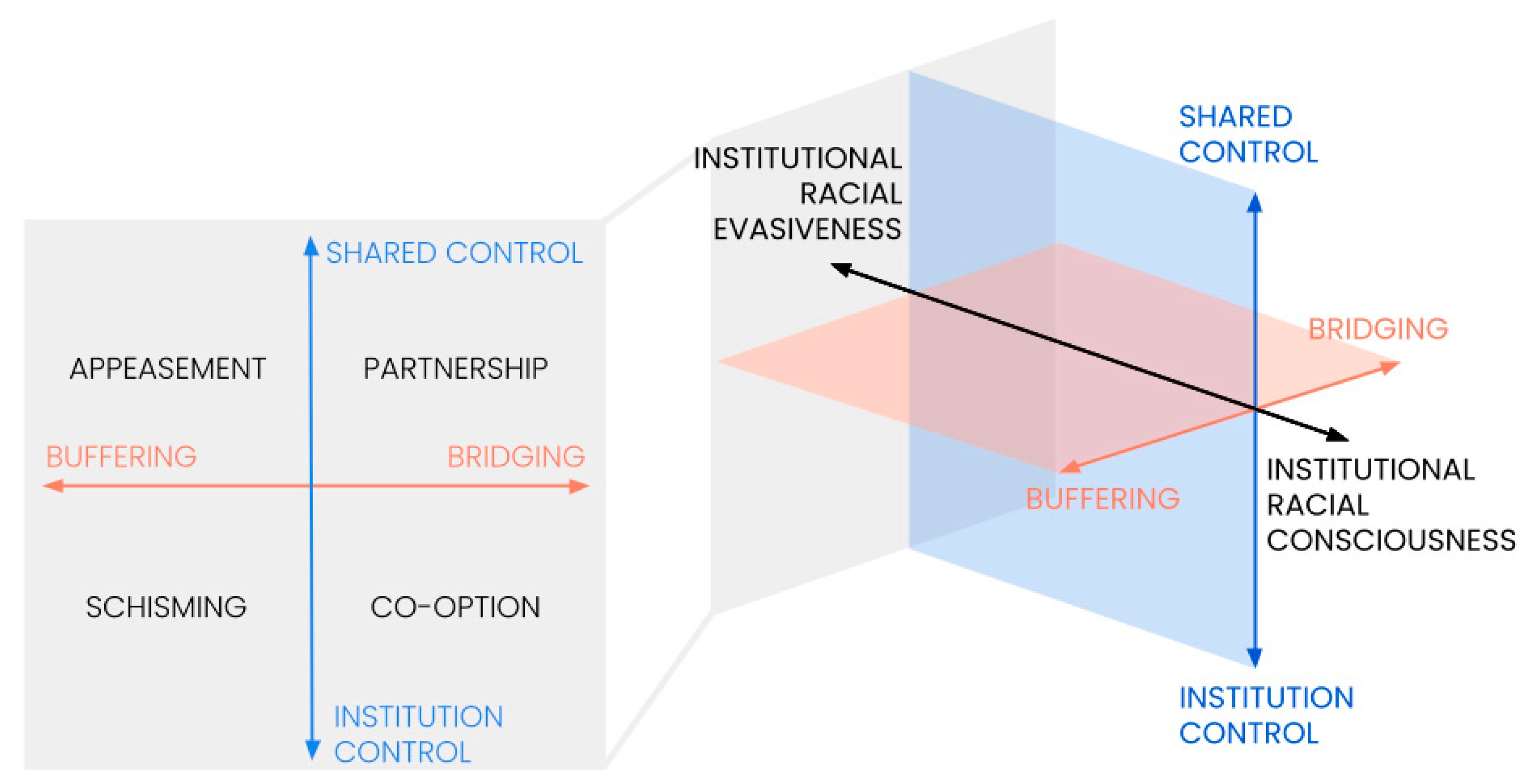

Drawing on the Institutional Response Framework [

6], this study utilizes discourse analysis to examine governance board minutes and recorded videos of two university boards in the southern United States from 2015 to 2018. More specifically, we examine how the governance boards at the University of Virginia and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill frame their policies on diversity, equity, race, and inclusion as a response, in part, to student and faculty activism. Study findings illustrate how deeply ingrained responses are within university branding, impacted by board membership, and subject to state policies.

4. Materials, Methods, and Overall Research Design

To examine the role of governance boards and their response to student activism efforts, we utilized critical discourse analysis to better understand “the institution” within institutional responses. Specifically, we examined two public universities (for accessibility) and their respective governance board systems. In addition, we specifically chose institutions with highly publicized national student protests to illuminate the tension and accountability boards face in respective to their university brand and reputation. The study time-period was from 2015 to 2018 with additional historical and archival methods to contextualize this time frame. Leaning on case study’s concept of literal replication—or choosing cases that were similar to one another see [

20]—we determined the sites as the University of Virginia (UVA, Charlottesville, VA, USA) and the University of North Carolina (UNCCH, Chapel Hill, NC, USA). With both universities being public and all information being publicly available, we intentionally chose to not anonymize the institutions, which also ensures more detailed descriptions.

4.1. Institutional Context

Both UVA and UNCCH reside in the geographic South within the United States, with historic (and arguably still present) ties to slavery [

4]. Both universities are the public flagship universities of their respective states, though UNCCH is the flagship campus within the larger UNC system. The UNC system has a system-wide board, the Board of Governors, but each campus within the system has its own Board of Trustees. Both institutions are research-intensive universities (by the Carnegie Classification system), with strong athletic programs, and robust alumni engagement. In Fall 2015, racial demographics at both universities were approximately 70 percent white, and within the 2015 to 2018 time frame, both had campus-wide events and student protests that made national headlines. By the end of 2018, both UVA and UNC Chapel Hill’s most senior leadership, their president and chancellor, respectively, resigned.

In terms of board composition, UVA’s Board of Visitors consists of 17 members, along with two non-voting members, a faculty representative and student representative. The 17 voting members are appointed by the governor and out of the total, 12 must be university alumni. Board terms for voting members are four years with an option to renew for one additional year; non-voting members serve one-year terms. The chair of the Board of Visitors, or the rector, serves a one-year term. Together, these 19 members meet approximately seven times a year, which includes an annual retreat; specific committees such as those related to finance, grounds, academic life, meet additionally. For UNC Chapel Hill, their Board of Trustees is 13 members, for which 8 are determined by the larger UNC Board of Governors, 4 are appointed by the North Carolina General Assembly, and 1 is the student body president as an ex-officio member. Like UVA, terms are four years with the ability to renew a term, for a maximum of 8 consecutive years served. While the UNC Chapel Hill Board of Trustees meet approximately six times a year, and additional meetings for committees, they held emergency meetings in 2018 following the student protests that led to the toppling of Silent Sam.

Two important distinctions for both institutions are their positional context. UVA made academic headlines in 2012 when its then-rector attempted to remove the president and violated academic governance [

21]. With weeks of student and alumni protests following the abrupt termination, the president was reinstated and served until her resignation in 2018. This socio-political history serves as a critical juncture in the relationship between UVA, its board, president, alumni, and students. UNCCH’s position in the larger UNC system places an additional layer of coordinating with its Board of Trustees and senior leadership also needing to respond to the UNC Board of Governors and the UNC system-wide president.

4.2. Materials and Data Collection

Central to the data collection were the campus documents related to the respective boards of the UVA’s Board of Visitors and the campus-level board of UNCCH, the Board of Trustees. For these respective boards, the data corpus included not only board minutes and agendas, but also included the slide decks, notes from sub-committee meetings, related interviews with the student and/or local newspaper, as well as transcripts from publicly recorded board meetings.

With the University of Virginia, their Board of Visitors had 21 regular meetings between 2015 to 2018. Within the board, we examined specific committees, such as the Diversity and Inclusion Committee, that had clear connections to students’ concerns with racism and racial relations. Moreover, we also examined other committees such as the Building and Grounds Committee given that some of the racism-related concerns from students included renaming buildings, and utilized snowball networking for when other committees were referenced. Page lengths for committees were from 7 to 30 pages and whole board meetings could easily be well over 300 pages when including appendices. For the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and their Board of Trustees, in addition to the process utilized for the University of Virginia, we also specifically searched for terms related to their most well-known student protests between 2015–2018: the Confederate statue known as “Silent Sam” specifically with the Board of Governors (and the larger North Carolina system). In all, these documents were well over 200 in number.

In addition to data corpus related to UVA’s and UNCCH’s respective boards, we also explored the flagship student newspaper publications. We chose this avenue of triangulation given the cyclical dynamic of student protests and racism-related concerns on campus (see [

6,

22], and examined over 2500 student articles that were related to their concerns, demands, and protests regarding campus racism. Articles were determined through search terms such as “protest,” “board,” and “racism” and then read through for relevancy and connection.

4.3. Data Analysis

Prior to conducting data analysis, we developed institutional reports through campus archives, secondary historical information, as well as drawing from demographic data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. These institutional reports provided both historical and current context for what then set the stage for analysis. Moreover, the reports illuminated repeated patterns and influence of positional power (regarding board decisions). These patterns helped shape our initial analysis and categorizing of broad themes (similar to Iverson [

23]), to then engage in first cycle coding through in vivo

codes (see [

24]). These initial codes and broad themes then helped shape the second cycle of coding that utilized Saldaña’s

values coding [

22] to specifically look at the way each of the campus boards might be framing their argumentation through values and mission-like language. Given the data corpus size, our coding centered on larger bucketed themes [

25], through the qualitative software Dedoose, that would then illuminate which documents would be analyze for a more in-depth approach with critical discourse analysis and considering the role of power (see [

22]).

To engage in critical discourse analysis (CDA), we narrowed the data corpus to identify a select number of documents—often those with multiple codes and earmarked as “mic drop” to signal importance. Concretely, codes such as “contraction” under the values-coding served as points of interest as these texts often suggest multiple and/or conflicting values at hand that could benefit from being examined through CDA. Critical discourse analysis offers an analytical frame to engage with text and dialogue to interrogate the multifaceted and multi-layered dynamics of power, people, and position [

26]—specifically offering distinctions between what was said, what was perceived, and how positional differences (e.g., student, board member) changed what was communicated. For example, the language of “best interests” begs the question of best interests for what and for whom, and this framing became a pivotal finding of this study.

After the institutional reports, broad qualitative analysis, and more in-depth analysis, we determined initial findings through a racialized lens and particularly scrutinized how racial evasiveness could be masked in word choices, and phrases. By focusing first on specific themes through CDA, we were then able to map these findings back to the larger, broader themes across the multitude of institutional statements. As such, these findings were then drawn from not only the specific words or phrases from Board minutes, but then contextualized with student articles and campus contexts to determine the engagement and reactions of UVA and UNCCH’s governance boards and their respective student activists, specifically related to issues of DEI and racism.

5. Results

From our analysis, we concretized four findings specifically related to the framing of history, peer comparisons, protecting institutional interests, and restructuring priorities. More specifically, findings reveal how boards attempt to address racist histories and racism-based student protests without explicitly naming racism. In doing so, both UVA and UNCCH utilize institutional interests as a neutral goal, without acknowledging the ways this framing is racially evasive, especially with its impact on marginalized communities. To better understand these findings, we first outline the main concerns students at UVA and UNCCH had regarding their respective campus’s responses to racism and DEI efforts.

5.1. Student Activism and their Concerns

At both UVA and UNC Chapel Hill, student concerns regarding campus racism are two-fold: the first is based on contemporary contexts and specific manifestations of racism on their campus (during the 2015–2018) period; the second is rooted in the respective histories and legacies both universities have in relationship to slavery, the Confederacy, and the KKK.

For the students at UVA, their contention with history is deeply intertwined with its founder, Thomas Jefferson, and how despite his declaration for rights and freedom, remained a slaveholder. More specifically, their concerns centered on UVA’s continued celebration of the founder, without reconciling Jefferson’s role in maintaining slavey. Similarly, students additionally had concerns about the university’s lack of acknowledgment of the enslaved Black laborers who constructed the university. For them, these historical roots are intertwined with the continuous fight that Students of Color, and especially Black students, have had to engage to exist at the university. By the start of 2015, several decades of reports had been written, both by student groups and by administrative task forces, at the state of affairs for racially marginalized students and the ways they remain unsupported. This then boils over into the start of 2015, with two key events at UVA: the police-brutality of Martese Johnson, a Black student, in 2015; and the “Unite the Right” white supremacist rally in Charlotteville and the campus in 2017, which led to subsequent protests in response and the student demands to remove the statue of Thomas Jefferson.

At UNC Chapel Hill, students’ concerns are deeply intertwined with the university’s history with the Confederacy and the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). This is focused not only on the naming of specific buildings (e.g., what used to be known as Saunders Hall) or landmarks (like Confederate statue, Silent Sam), but also white supremacist ideals that remain ever present on campus. With these decades of student protests, students, especially the Black student groups and activists at UNC Chapel Hill, actively advocated for the renaming of monuments and campus symbols to celebrate Black activists (such as what would become the Sonja Haynes Stone Center). The cycles of continued protests came to a head in 2015 over several KKK-affiliated buildings and again in 2017 and 2018 over the year-long protests regarding Silent Sam. These protests, which amassed hundreds and thousands of allies and counter protesters, sparked further conversations about the role of campus police, the responsibility of the university to keep students safe, and what it means to contend with history.

5.2. Reframing History and Student Concerns

Across the data corpus, one of the main disconnects in documentation was the difference of how student articles discussed racialized manifestations on campus or campus history, compared to the framing and language used within board meeting minutes. Board language was much broader and often centered on issues that felt not quite aligned with protests or demands. Instead of explicit reference to racism, the conversations were much more centered on diversity and inclusion. For example, UNCCH’s framing and connection to the Confederate centered on a “troubled past” and “controversial history” rather than explicitly naming the foundational issue, white supremacy. Similar at UVA, following the assault and police brutality against Johnson at UVA, which many students linked to enduring campus racism, the March 2015 minutes from the Diversity Committee internally contextualized how they are “[seeing] an awful lot of upsetting information about… the application of the criminal justice system to the African American community and in particular African American men.” In many ways, having the specific reference to African American men and the injustices of the criminal justice system is an important acknowledgement. Yet, for students, particularly student activists, this might still be evading what they view as the core issue. During that same meeting, when racism was explicitly named, it was by the student presenters, invited by UVA’s Board of Visitors.

Framing issues as troublesome, upsetting or controversial, offers potential for interpretation which might be necessary given the wide spectrum of political opinions and perspectives governance boards engage. This hedging towards ambiguity can conversely also be concretized because of context—especially in the wake of tragedy or crisis. While the Unite the Right rally prompted an emergency meeting for UVA’s Board of Visitors, the explicit references to white supremacy were found not in the board meetings and what can be seen as internal minutes, but instead in remarks from the rector to the entire campus. However, in the following months, the comments follow the hedging type patterns of interpretation. Due to the purpose of the board in determining university mission and maintaining the financial health of the university, which includes navigating different audiences—potentially local, state, and federal policy makers—the framing and language reflects within this pattern, rather than explicit language towards racial justice.

5.3. Comparative Reputation and Peer Pressure

As evidenced across the data corpus within each institution, boards consistently discussed rankings and benchmarks of peer institutions (especially during the times rankings were annually announced). Board of Trustee members described UNC Chapel Hill’s placement in Kiplinger’s Personal Finance Rankings, and the October 2015 board minutes included the following statement, “this [U.S. World News and Report ranking] is one that universities, high school students and parents across the country pay attention to. It’s reassuring to know we’re keeping good company with the best peer public and private campuses.” Note the usage of “good company” and “best peer” that convey meaning without clear definition of what constitutes either category, except a validation with rankings.

At the same time, the gravitation towards peer institutions offers an opportunity to create comparative standards for academic success. For example, the board explored the faculty retention practices of Vanderbilt University and the University of California, Berkeley to gain insight into their own efforts. These peer institution comparisons were more than the adoption or adaptation of exemplar practices. The Board of Visitor reliance on examining UVA’s peer institutions bled into their rationale for the decision-making process, with conversations about diversity being related to institutional branding, reputation, rankings, and what is the quality of education they offer.

With governance boards focused on keeping up with peer institutions, the commitment towards faculty diversity is less a response towards student concerns about racial representation, but more a concern about how losing Faculty of Color will negatively impact retention, recruitment, scholarship production, and ultimately rankings. Metrics, as seen in UVA’s June 2015 Diversity and Inclusion Committee, are framed as “Where we stand compared to AAU peers” for their faculty diversity plan. This rationale is one that students both understand and utilize. For example, when students pressed to departmentalize the African American and African Studies program during 2016–2017, then-student body president, Daniel Judge included the following in his statement:

Almost all of our peer institutions already have departments. These include, but are not limited to, UCLA, UC Berkeley, Syracuse, Duke, UNC, Harvard, and Yale. These departments have been successful and we would likely experience a similar success.

Likewise in 2018, UVA student groups, Asian Leaders Council and the Latinx Student Alliance, referenced peer institutions in their respective demands about creating an Asian American Studies department and a Latinx space on campus. In all three examples, students have consistently utilized the language of “success” to align with the board’s emphasis on quality. While some could argue that this emphasis on quality problematically does not include a rationale or intersection with racial justices, others would point to this as a phenomenon of interest-convergence and co-option so that programs receive institutional support. In doing so, this institutional support, though vaguely defined through a lens of quality, offers the opportunity for institutionalized racial consciousness and supporting the demands of marginalized students.

Moreover, board adoptions of racially oriented decisions, can well align with a desire to be ahead of the times, or to be first. For example, UVA’s Buildings and Grounds Committee (a committee within the Board of visitors) renamed the Alderman Road Residence Hall Building #6” to “Gibbons House” for enslaved Black couple William and Isabella Gibbons. In doing so, then-Rector Martin observes the significance of this decision, stating how “there are few peer institutions that have named buildings after slaves.” UVA founded Universities Studying Slavery, a consortium of over 90 members examining the relationship between the campus and slavery, where the public messaging for UVA has been lauded one of the first of its kinds.

5.4. A University’s “Best Interests”

For the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill a common framing within their Board of Trustee meeting minutes was the language of “best interest.” UNC Chapel Hill’s reputation includes not only a relationship to ranking, but also a relationship to state-wide perceptions. More specifically the university often utilized the phrase “Carolina’s best interest” without clear distinction whether board members were speaking about the university or the state. This ambiguity reflects the tenuous relationship and pressure the flagship university felt in responding to state concerns and upholding reputation. For example, the opening remarks from then-Board of Trustee chair Lawrey Caudill for the January 2015 meeting included how, “Carolina is positioned to lead and deliver and have tremendous impact on the state of North Carolina.” This well aligns with what then-Governor Pat McCrory emphasized earlier in the day, with the, “need to commercialize research efforts at our universities.” The emphasis on commercial value and economic impact can also be traced to their diversity efforts, specifically with the phrase of “inclusive excellence.” Inclusive excellence, as defined by the Board, “operates from the premise that diversity and inclusion are woven into the fabric of the institution and are essential to an institution achieving excellence and success and realizing the educational benefits of diversity.” While this definition both necessitates inclusion to the university’s “best interests,” it also names diversity as a commodity to gain.

What is most interesting about the board’s framing of “Carolina’s best interest” is the ambiguity of the statement. Prior to the 26 March 2015 board meeting, many of the campus Black student activists and allied student groups held protests and demonstrations regarding the namesake of Saunders Hall, whose numerous roles and positions included previously serving as the Head of the Clan of the North Carolina KKK chapter. The conversation about the university’s “best interests” to potentially rename Saunders Hall was framed in how to preserve university history rather than the specific concerns outlined by students (such as feeling alienated by this building name). The May 2015 vote to ultimately rename Saunders Hall was successful, only after the explicit record of Saunder’s KKK activities, as then-board vice chair Garner outlined from the original 1920 recommendation. What is illuminating here is that the tipping point was not the student activism and their concerns, but rather the explicit connection between KKK and the university’s history. For BOT members like Trustee Clay and Secretary Shuping-Russell, this detail proved to be a “game changer for everyone.” In doing so, this aligns with a longstanding concern about not being on the wrong side of history, another reference to maintaining their reputation for “Carolina’s best interests.” This language was seen again throughout the continued series of student protests and emergency meetings related to the 2017 and 2018 student protests regarding Silent Sam. The utilization of right versus wrong for how the university addresses its history, while seemingly tied to racial justice, is still rooted in racial evasiveness given the terms’ abilities to be interpreted regardless of racism and racial progress.

5.5. Board Priorities through Structure and Policy

Within a larger scope of structure, both UVA and UNC Chapel Hill had designated committees related to diversity. However, UVA’s Board of Visitors absorbed the committee into its larger Board of Visitors role in the beginning of August 2016. The board maintained this decision and stated in 2017, following student concerns to reinstate a diversity committee, with then-Rector Conner explaining that, “diversity and inclusion [should] be the responsibility of the entire Board and not just assigned to one committee.” Yet, when taking a closer look at this absorption and restructuring, the question remains whether diversity and inclusion is a priority when dispersed as everyone’s commitment.

From September 2015 to 2016, conversations regarding race and racial diversity appeared in each of the 7 board meetings, as well as related committee meetings, which encompassed 22 documents. In comparison, for the two years that followed, from September 2016 to December 2018, the topic of race was discussed 8 times, within the 44 documents spanning the 14 regular board meetings and additional committee meetings. More specifically, of the 8 instances, two were related to the Dean’s working group and their reporting out of progress, not from the Board of Visitors. The more than 50 percent decrease in the board’s conversations regarding racial diversity suggests that the August 2016 decision to absorb diversity efforts, might be more aptly described as a dissolving diversity efforts. Yet, when asked about the progress during one of the 2017 board meetings, Connor described how, “contrary to what some people believe, the University is making remarkable progress on diversity, and is putting substantial resources into increasing diversity. It has been the highest priority over the last three to four years.”

Board structures reinforce university priorities with not only the types of committees that they have created, but also the ways that they structure their meetings. Both UVA and UNC Chapel Hill student newspapers have commented on the lack of access to their respective board meetings. UVA students in particular, have protested about the inability to protest at their board meetings, citing that it is a system to shut out their voices. This is even more compounded in the types of policies that boards can approve. For example, the 2015 decision from the UNC Chapel Hill Board of Trustees to rename Saunders Hall to Carolina Hall (which went against students’ demands for it to be renamed to Zora Neale Hurston Hall), also included a 16-year moratorium that would prevent the renaming of buildings. While this policy was revoked in 2020, this type of policy making can dramatically impact the agency of student activists and their demands.