COVID-19 the Gateway for Future Learning: The Impact of Online Teaching on the Future Learning Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. COVID-19 and Distance Learning: Challenges and Opportunities

2.2. Beyond Learning during COVID-19

2.3. Different Future Students, Different Future Needs

2.4. The Future Learning

3. Research Question

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

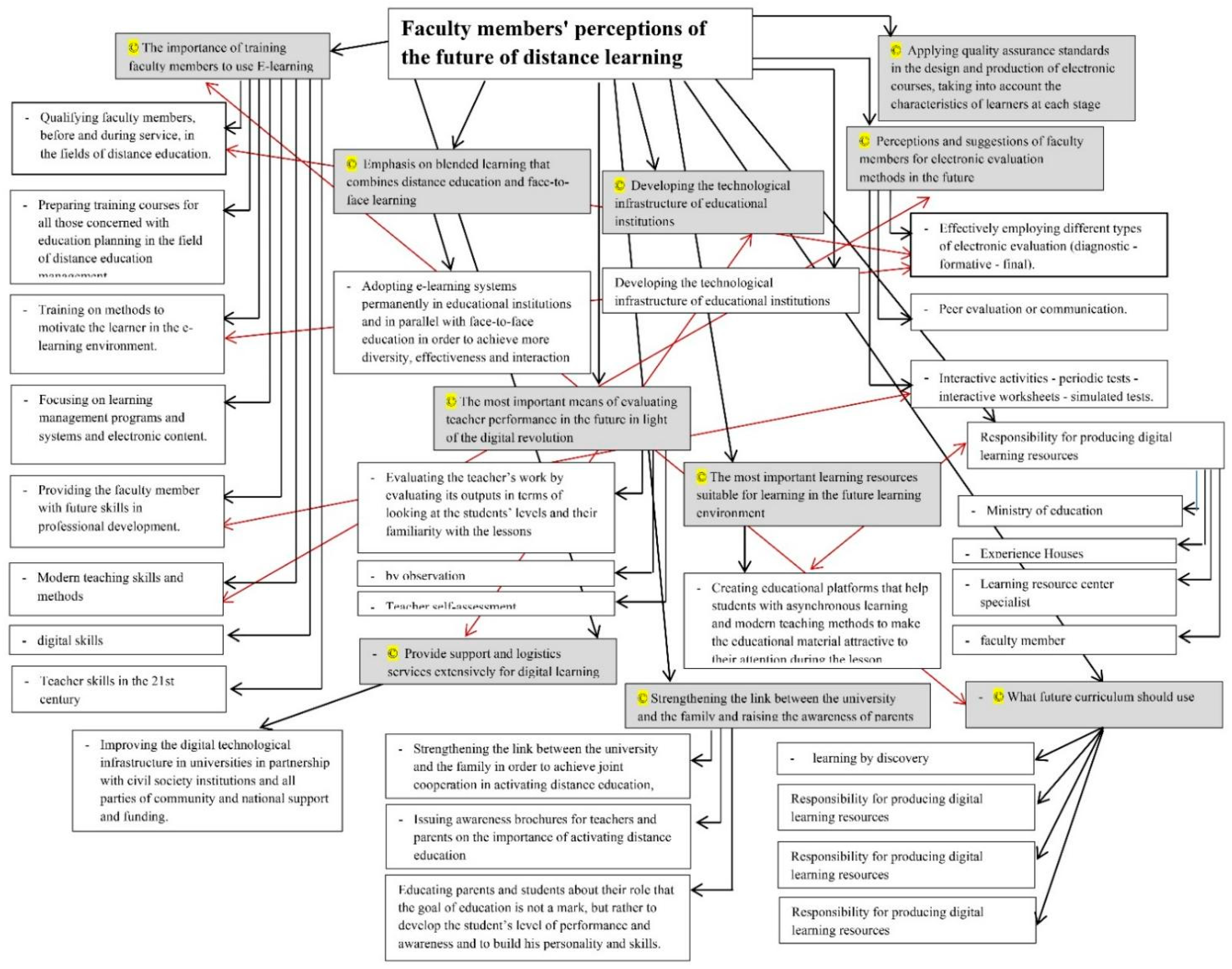

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Results

5.1.1. Staff s’ Future Needs

- “It is necessary to reconsider staff training with the emergence of remote training to better comprehend its future role in raising awareness and training instructors” (pos. 19).

- “Developing staff’s technical skills are reflected in their improved performance, making it easier for them to communicate with students and develop course presentation processes. This enables the staff to smoothly clarify the content of the course, facilitating materials handling” (pos. 38).

- “Post-COVID-19, staff is forced to develop alternative means and use technology in education. It has become important to improve the applications and programs that enable him to enhance their subject presentation” (pos. 72).

- “Familiarity with a 21st Century staff skillset, an emphasis on LMS programs, and familiarity with modern technology tools are necessary technological skills” (pos. 53 & pos. 51).

- “Staff’s position hasn’t altered much in light of the epidemic, but the challenges have grown. They must be competent to overcome them and efficiently offer educational content” (pos. 22).

5.1.2. Future Hybrid Learning

- “Hybrid education promotes the efficient diversification of teaching techniques and the development of skills for students” (pos. 21).

- “By integrating distant learning and F2F, education becomes more flexible” (pos. 31).

- “To attain more diversity, effectiveness, and interactivity, e-learning technologies are permanently employed in parallel with F2F education in educational institutions” (pos. 43).

5.1.3. Curriculum, Teaching Strategies, and Pedagogy

- “Some staff have been struggling with supporting colleagues during the crisis (some staff has created their own support groups inside departments) and how to guarantee students’ learning” (pos. 3).

- “Equality and a reduction in student anxiety should be prioritized. Staff should not rely excessively on simultaneous video conferencing to include students with poor internet infrastructure or other family members who need internet bandwidth for other purposes” (pos. 14).

- “It appears that my teaching priorities have shifted. Rather than pondering how to transmit what I’ve learned, I’ve decided to convert my courses to a distant learning environment using appropriate electronic teaching methods” (pos. 5).

- “Student-centered design is required for online learning. Focus on content alone will produce poor ineffective multimedia” (pos. 28).

- “We can include listening to a podcast, reading a text, or watching a video among the things students should do. This necessitates a thorough analysis of the task, (position 29), i.e., thinking about the practical aspects. (pos. 12)”.

- “Online learning relies more on material (readings, videos, exercises, etc.) than on direct in-person interactions (discussions, presentations, etc.), but teachers must source usable good material; on the other hand, it requires students’ independence to interact with multimedia (pos. 13)”.

- “A precise preemptive design is required for e-teaching (pos. 18)”.

5.1.4. Future Educational Infrastructure, Support, and Logistics

- “It is critical to improve the structure of e-learning and technological infrastructure and equipment in universities (pos. 82)”.

- “We must address the internet’s weaknesses obstructing future communication with the instructor (pos. 28)”.

- “The IoT is used to disseminate knowledge across all aspects of the learning environment (pos. 49 & pos. 15)”.

- “Using iPads or smart devices with the students to convert books into interactive e-books with rich multimedia (pos. 19)”.

- “Building instructional digital content production centers at universities (pos. 82), providing them with cutting-edge equipment and specialists in digital content production (pos. 34)”.

5.1.5. Assessment of Learners’ Performance

- “Using current electronic technologies in assessment, such as Microsoft Teams’ reading progress, to improve the assessment process (pos. 67)”.

- “Activating some features of approved e-learning programs expands the use of educational applications for evaluation (pos. 17)”.

- “It is important to use various types of e-assessment effectively (pos. 35) to measure diverse learners’ skills (pos. 34)”.

- “Assessment tools should be diverse (pos. 87) to increase interest in e-discussions and e-projects, peer evaluation, and the development of more technical assessment instruments (pos. 16)”.

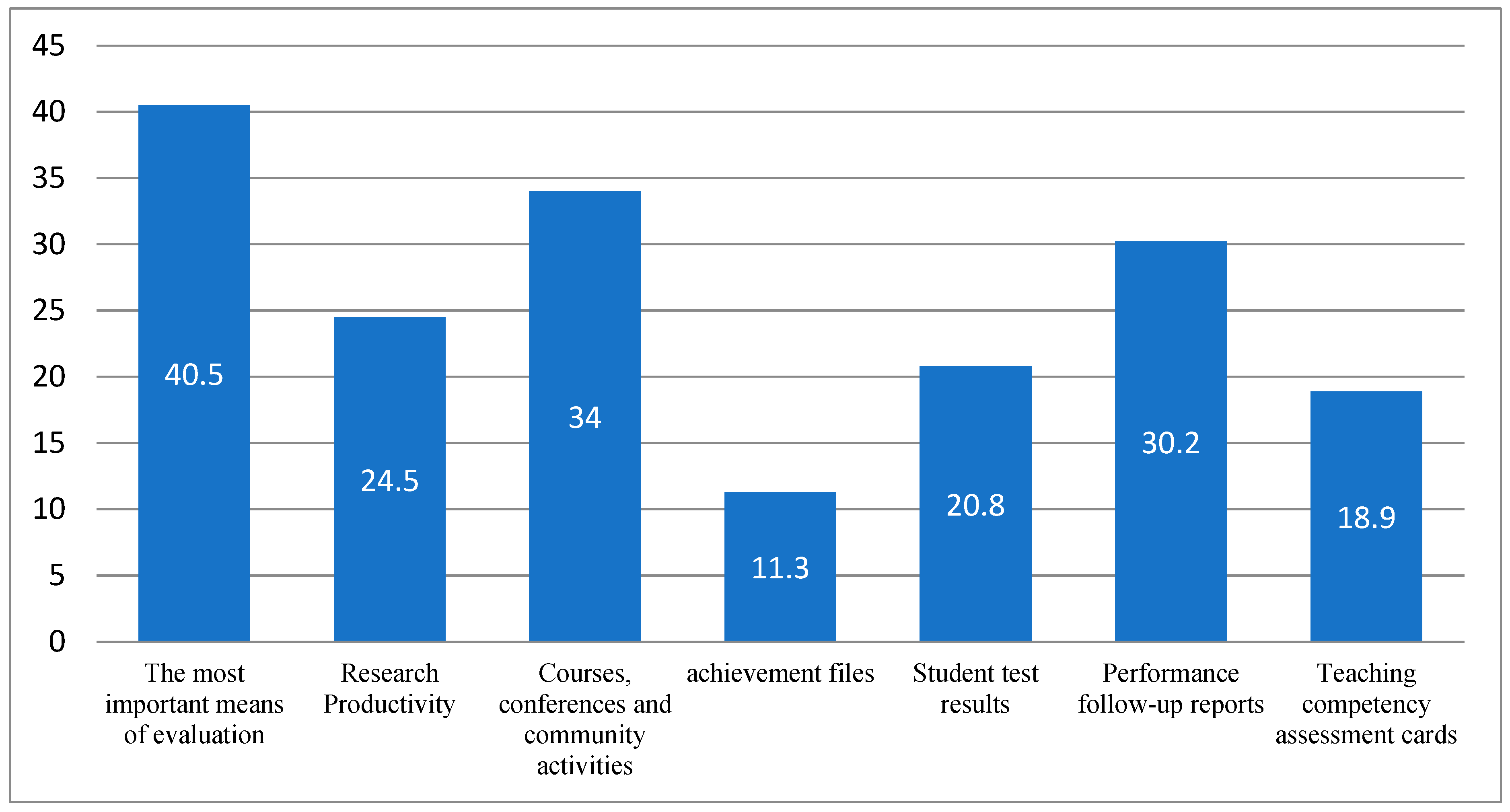

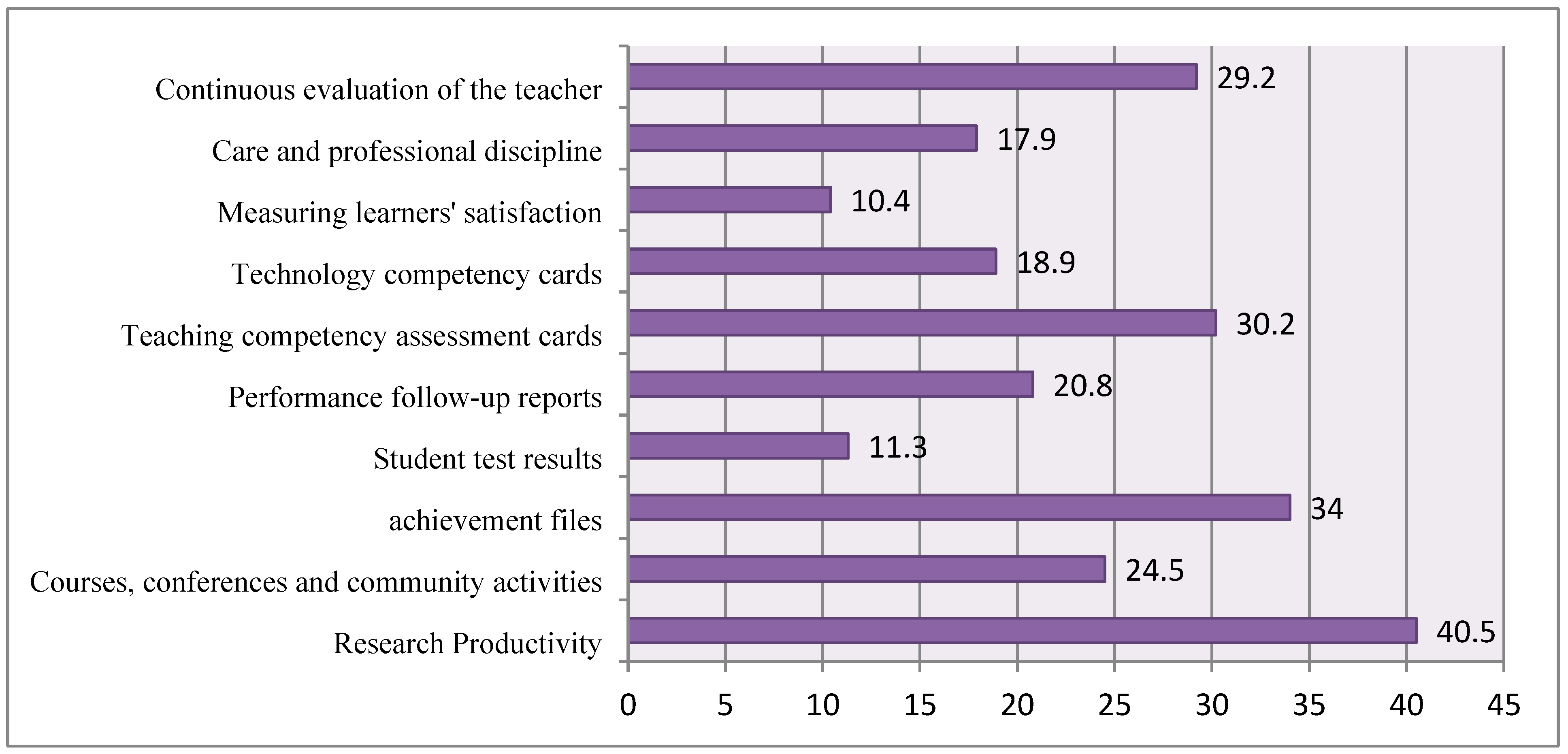

5.1.6. Future Staff Assessment

- “Teacher assessment approaches that enhance learning and achievement metrics improve retention of and performance of teachers (pos. 42)”.

- “It is important to improve staff’s proficiency in ICT use, particularly educational applications software, and to be trained for specialization, the extent to which behavioral characteristics and individual differences are activated”.

- “A teacher’s performance is effectively evaluated to assess student’s understanding. Some argue that this is unfair due to some students’ poor and unhandled quality—although a minority. Yet, the instructor must raise his students’ standards using all available tools (pos. 39)”.

5.1.7. Modern Trends in Educational Technology

- “It is important to source educational platforms that assist students with asynchronous learning and modern teaching methods (pos. 121)”.

- “Using tablets, best social communication methods, designing user-friendly websites, localizing appropriate technology from some educationally experienced countries, providing appropriate references for all sciences for free or at nominal prices uploading and making curricula available on appropriate media. The Ministry of Education should offer relevant educational resources for all disciplines, and for the community to participate through institutions and civic society to encourage digital advancement in all educational activities (pos. 129)”.

- “The Ministry of Education and private sector firms are responsible for producing the resources (pos. 121)”.

- Unique programs: interactive learning, cyber security, smart programs, interactive multimedia design, montage, and digital transformation.

- Programs that combine personal and technical components, e.g., time management, digital skills and statistics, artificial intelligence, 21st century skills, and cloud computing.

- Purely technical programs, such as design and production abilities for multimedia, and the usage of instructional platforms, infographic design programs, programming, learning analytics, and data mining.

5.1.8. Parents’ Roles in Future Learning

- “Some parents neglect to follow up on their sons, and we hope that as a result of this problem, parents will be more aware of the need of encouraging and motivating their sons to study” (pos. 25).

- “Some parents may receive a high rating, while others may receive a low rating due to their lack of cooperation and interaction with the university. The cooperation of parents might be invested in future positions where the university collaborates with parents” (pos. 27).

- “Parents can be inspired and encouraged to maximize their future role by paying attention to their children’s attendance, completing projects and tests, attending lectures, and following up” (pos. 30).

5.2. Discussion

5.3. Limitations

5.4. Recommendations

5.4.1. Staffs’ Future Needs

5.4.2. Future Hybrid Learning

5.4.3. For Curriculum, Teaching Strategies, and Curricula

5.4.4. For Future Educational Infrastructure, Support, and Logistics

5.4.5. Assessment of Learners’ Performance

5.4.6. For Future Staff Assessment

5.4.7. Modern Trends in Educational Technology

5.4.8. For Parents Roles in Future Learning

5.5. Implications of the Study

- The paradigm shift in learning from the traditional site-bound paradigm toward the new CMITriplization paradigm with an emphasis on individualization (human motivation and potential and creativity of the individuals), localization (local resources, community support, and cultural relevance), and globalization (global networking, international support, and world-class resources) in learning

- Building up ecosystems supported by systemic changes in culture, technology, and the paradigm of education for new e-learning through interactive AI technologies, students’ self-initiative, and e-learning ecosystems instead of e-text or materials

- The availability of a digital learning objects repository for staff

- A focus on socially connected, learner-centered activities that allow educators to develop knowledge and skills in teaching with technology in any format or situation

- The adoption of unstructured professional development, e.g., mentoring, online forums, or virtual learning groups

- Developing learning theories to develop an effective remote teaching and virtual learning curriculum

- The approval of a set of professional certificates in information and communication technology for teachers based on the Massive Open Online System Courses (MOOCs)

- Building a strong information infrastructure that helps the flow of data between learning networks and employing the IoT and relying on the analysis of Big Data generated by social networking sites for students

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daniel, S.J. Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects 2020, 49, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, S. The future of business education: A commentary in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofianidis, A.; Meletiou-Mavrotheris, M.; Konstantinou, P.; Stylianidou, N.; Katzis, K. Let students talk about emergency remote teaching experience: Secondary students’ perceptions on their experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawa, P. Learning in the age of SARS-CoV-2: A quantitative study of learners’ performance in the age of emergency remote teaching. Comput. Educ. Open 2020, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basilaia, G.; Kvavadze, D. Transition to online education in schools during a SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 5, em0060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, C. Discussing the Future of Education, 17 August 2016. Available online: https://elearningindustry.com/discussing-future-of-education (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Cahyadi, A.; Widyastuti, S.; Mufidah, V.N. Emergency remote teaching evaluation of the higher education in Indonesia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, J. Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Jnr, B.A.; Noel, S. Examining the adoption of emergency remote teaching and virtual learning during and after COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2021, 35, 1136–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, G.; Grenha Teixeira, J.; Torres, A.; Morais, C. An exploratory study on the emergency remote education experience of higher education students and teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1357–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedoyin, O.B.; Soykan, E. COVID-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Watterston, J. The changes we need: Education post COVID-19. J. Educ. Chang. 2021, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, G. Changes within the Teaching Pedagogy Driven by COVID-19: Viewpoints and Analysis. Res. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 12, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karaki, J.N.; Ababneh, N.; Hamid, Y.; Gawanmeh, A. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Distance Learning in Higher Education during COVID-19 Global Crisis: UAE Educators’ Perspectives. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2021, 13, 311–334. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Wu, S.; Zhou, M.; Li, F. ‘School’s out, but class’ on’, the largest online education in the world today: Taking China’s practical exploration during the COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control as an example. Best Evid. Chin. Edu. 2020, 4, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, F. Post-COVID-19 Transition in University Physics Courses: A Case of Study in a Mexican University. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbules, N.C.; Fan, G.; Repp, P. Five trends of education and technology in a sustainable future. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Sancho, Á.; Vergara, D.; Fernández-Arias, P. Influence of country digitization level on digital pandemic stress. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguma, M.; Feron, E.; Lim, M. Future of Education and Skills 2030: Conceptual Learning Framework; Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2018.

- Ramos-Pla, A.; Reese, L.; Arce, C.; Balladares, J.; Fiallos, B. Teaching Online: Lessons Learned about Methodological Strategies in Postgraduate Studies. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelghoum, A.; Chelghoum, H. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Education: Big Changes ahead for Teaching in Algeria. ALTRALANG J. 2020, 2, 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Henny, C. Things That Will Shape the Future of Education: What Will Learning Look Like in 20 Years? eLearning Industry. Available online: https://elearningindustry.com/9-things-shape-future-of-education-learning-20-years (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Kusek, J.Z.; Rist, R.C. Ten Steps to a Results-Based Monitoring and Evaluation System; A Handbook for Development Practitioners; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/14926. (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Lucas, M.; Vicente, P.N. A double-edged sword: Teachers’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of online teaching and learning in higher education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J.; van Braak, J.; Siddiq, F.; Scherer, R. Time for a new approach to prepare future teachers for educational technology use its meaning and measurement. Comput. Educ. 2016, 94, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkareva, T.; Akhmetshin, E.; Osadchy, E.; Romanov, P.; Konovalova, E. Preparation of the future teacher for work with gifted children. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2018, 9, 251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Antón-Sancho, Á.; Sánchez-Calvo, M. Influence of Knowledge Area on the Use of Digital Tools during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Latin American Professors. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Remote Learning and COVID-19 the Use of Educational Technologies at Scale Across an Education System as a Result of Massive School Closings in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic to Enable Distance Education and Online Learning. 2020. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/266811584657843186/pdf/Rapid-Response-Briefing-Note-Remote-Learning-and-COVID-19-Outbreak.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Di Pietro, G.; Biagi, F.; Costa, P.; Karpiński, Z.; Mazza, J. The Likely Impact of COVID-19 on Education: Reflections Based on the Existing Literature and Recent International Datasets; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Volume 30275. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, C. Suspending classes without stopping learning: China’s education emergency management policy in the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W. Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. High. Educ. Stud. 2020, 10, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayapragassarazan, Z. COVID-19: Strategies for online engagement of remote learners. F1000Research 2020, 9, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya, K. Design considerations in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: A human-centered approach. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlanga, A.J.; Peñalvo, F.G.; Sloep, P.B. Towards Learning 2.0 University. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2010, 18, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, J.; Martinez, J.L.; Montoute, A.; Niles, K. Impacts of COVID-19 in the Commonwealth Caribbean: Key lessons. Round Table 2021, 110, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahem, U.M.; Alamro, A.R. The Effect of Using Cinemagraph Pictures in Social Platforms and Mobile Applications in the Development of Peace Concepts. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2021, 37, 1341–1361. [Google Scholar]

- Alioon, Y.; Delialioğlu, Ö. The effect of authentic m-learning activities on student engagement and motivation. British J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Aguilera, E. A critical approach to humanizing pedagogies in online teaching and learning. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2020, 37, 37–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Buntins, K.; Bedenlier, S.; Zawacki-Richter, O.; Kerres, M. Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: A systematic evidence map. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Alturki, U.; Alrobai, A.; Aldraiweesh, A.A.; Omar Alsayed, A.; Kamin, Y.B. Social media–based collaborative learning: The effect on learning success with the moderating role of cyberstalking and cyberbullying. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 30, 1434–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S.; Naama-Ghanayim, E. Why care about caring? Linking teachers’ caring and sense of meaning at work with students’ self-esteem, well-being, and school engagement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 91, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partington, A. Developing inclusive pedagogies in HE through an understanding of the Learner-Consumer: Promiscuity, Hybridisation, and Innovation. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2021, 3, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaran, T.; Yasin, M.H.M. Parental Support in the Learning of Students with Hearing Impaired at Home. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Special Education In South East Asia Region 10th Series 2020, Bangi Selangor, Malaysia, 29–30 March 2020; Redwhite Press: West Sumatra, Indonesia, 2020; pp. 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.H.; Liu, D.J.; Tlili, A.; Yang, J.F.; Wang, H.H. Handbook on Facilitating Flexible Learning during Educational Disruption: The Chinese Experience in Maintaining Undisrupted Learning in COVID-19 Outbreak; Smart Learning Institute of Beijing Normal University: Beijing, China, 2020; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, P.N.; Lucas, M.; Carlos, V.; Bem-Haja, P. Higher education in a material world: Constraints to digital innovation in Portuguese universities and polytechnic institutes. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 5815–5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Judd, J. COVID-19: Vulnerability and the power of privilege in a pandemic. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 31, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; McGee, R.; Nampoothiri, N.; Gaventa, J.; Forquilha, S.; Ibeh, Z.; Alex, S. Navigating Civic Space in a Time of COVID: Synthesis Report; Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office: London, UK, 2021.

- Czerniewicz, L. What We Learnt From “Going Online” during University Shutdowns in South Africa. 2020. Available online: https://philonedtech.com/what-we-learnt-from-goingonline-during-university-shutdowns-in-south-africa (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Oyedotun, T.D. Sudden change of pedagogy in education driven by COVID-19: Perspectives and evaluation from a developing country. Res. Glob. 2020, 2, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprisor, R.; Kwon, R. Multi-period portfolio optimization with investor views under regime switching. J. Risk Financial. Manag. 2020, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T.; Asghar, H.M. Technology use, self-directed learning, student engagement and academic performance: Examining the interrelations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleider, E.; Kreuzer, T.; Lösser, B.; Oberländer, A.M.; Eymann, T. Drivers and Barriers of the Digital Innovation Process–Case Study Insights from a German Public University. In International Conference on Business Process Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 437–454. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Demographic Information | n | % of Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | University | Hail University | 25 | 19.6 |

| Umm Al Qura University | 20 | 15.7 | ||

| Imam Muhammad Bin Saud Islamic University | 11 | 8.6 | ||

| Al Qussaim university | 15 | 11.8 | ||

| King Saud University | 12 | 9.4 | ||

| King Abdulaziz University | 11 | 8.6 | ||

| King Faisal University | 8 | 6.2 | ||

| Al Baha university | 13 | 10.2 | ||

| Imam Abdul Rahman bin Faisal University | 12 | 9.4 | ||

| 2 | Gender | Male | 51 | 40.2 |

| Female | 76 | 59.8 | ||

| 3 | Academic Rank | Professor | 20 | 15.7 |

| Associate Professor | 26 | 20.4 | ||

| Assistant Professor | 81 | 63. | ||

| 4 | Years of Experience | Less than 5 years | 62 | 48.8 |

| From 5 years to less than 10 years | 11 | 8.6 | ||

| From 10 years to less than 15 years | 18 | 14.1 | ||

| From 15 years to less than 20 years | 27 | 21.2 | ||

| From 20 years and over | 9 | 7.08 | ||

| The Question | Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| Faculty members’ perceptions of the future of distance learning | The importance of training faculty members to use E-learning |

|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Emphasis on blended learning that combines distance education and face-to-face learning |

| |

| The most important means of evaluating teacher performance in the future in light of the digital revolution |

| |

| ||

| ||

| Provide support and logistics services extensively for digital learning |

| |

| Developing the technological infrastructure of educational institutions | ||

| The most important learning resources suitable for learning in the future learning environment |

| |

| Strengthening the link between the university and the family and raising the awareness of parents |

| |

| ||

| ||

| Applying quality assurance standards in the design and production of electronic courses, taking into account the characteristics of learners at each stage | ||

| Perceptions and suggestions of faculty members for electronic evaluation methods in the future |

| |

| ||

| ||

| Responsibility for producing digital learning resources |

| |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| What future curriculum should use |

| |

| ||

| ||

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alharbi, B.A.; Ibrahem, U.M.; Moussa, M.A.; Abdelwahab, S.M.; Diab, H.M. COVID-19 the Gateway for Future Learning: The Impact of Online Teaching on the Future Learning Environment. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120917

Alharbi BA, Ibrahem UM, Moussa MA, Abdelwahab SM, Diab HM. COVID-19 the Gateway for Future Learning: The Impact of Online Teaching on the Future Learning Environment. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(12):917. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120917

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlharbi, Badr A., Usama M. Ibrahem, Mahmoud A. Moussa, Shimaa M. Abdelwahab, and Hanan M. Diab. 2022. "COVID-19 the Gateway for Future Learning: The Impact of Online Teaching on the Future Learning Environment" Education Sciences 12, no. 12: 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120917

APA StyleAlharbi, B. A., Ibrahem, U. M., Moussa, M. A., Abdelwahab, S. M., & Diab, H. M. (2022). COVID-19 the Gateway for Future Learning: The Impact of Online Teaching on the Future Learning Environment. Education Sciences, 12(12), 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120917