A Social Support and Resource Drain Exploration of the Bright and Dark Sides of Teachers’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. OCB and Work-Related Outcomes

3. Methods

Sample and Procedure

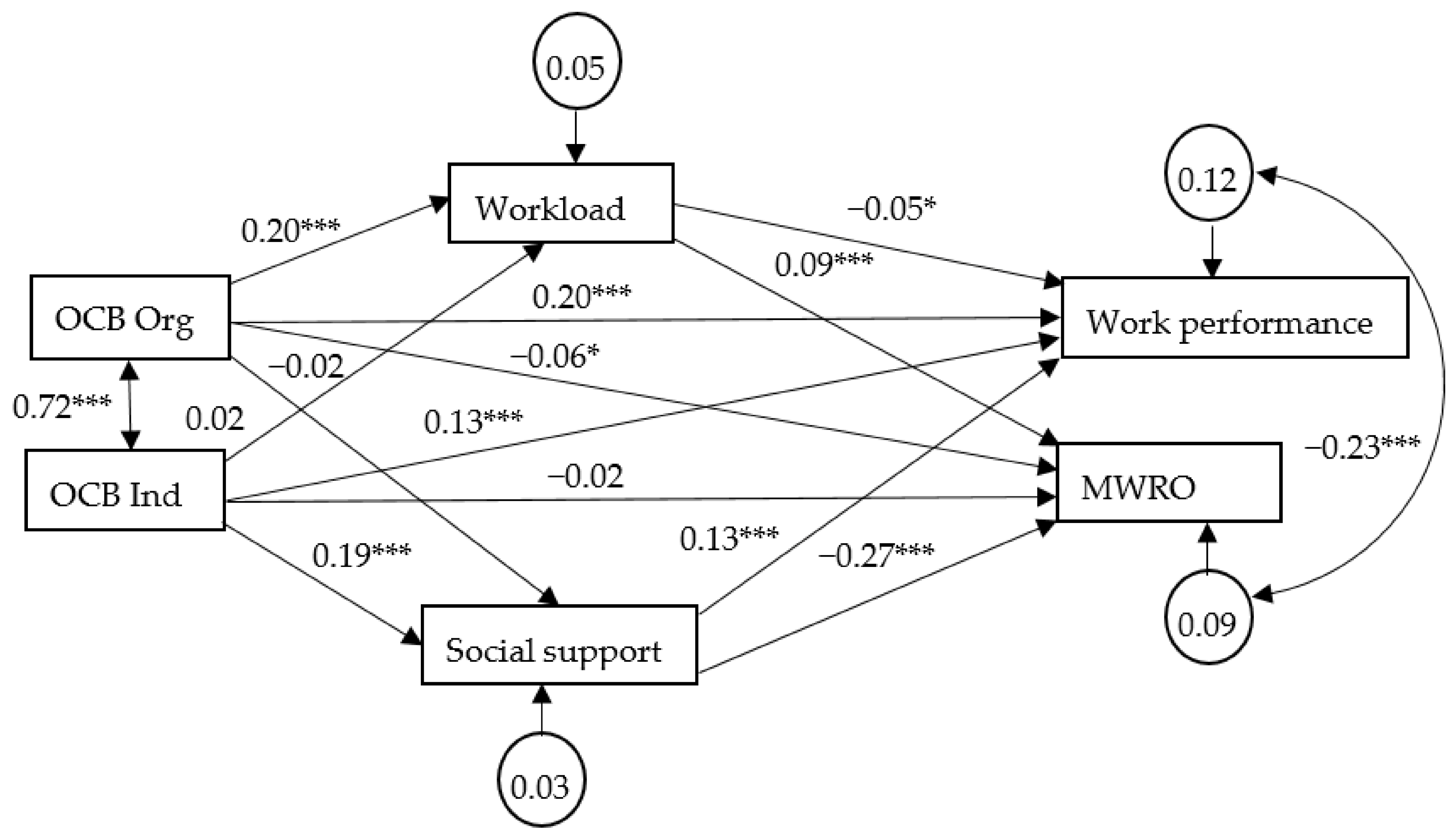

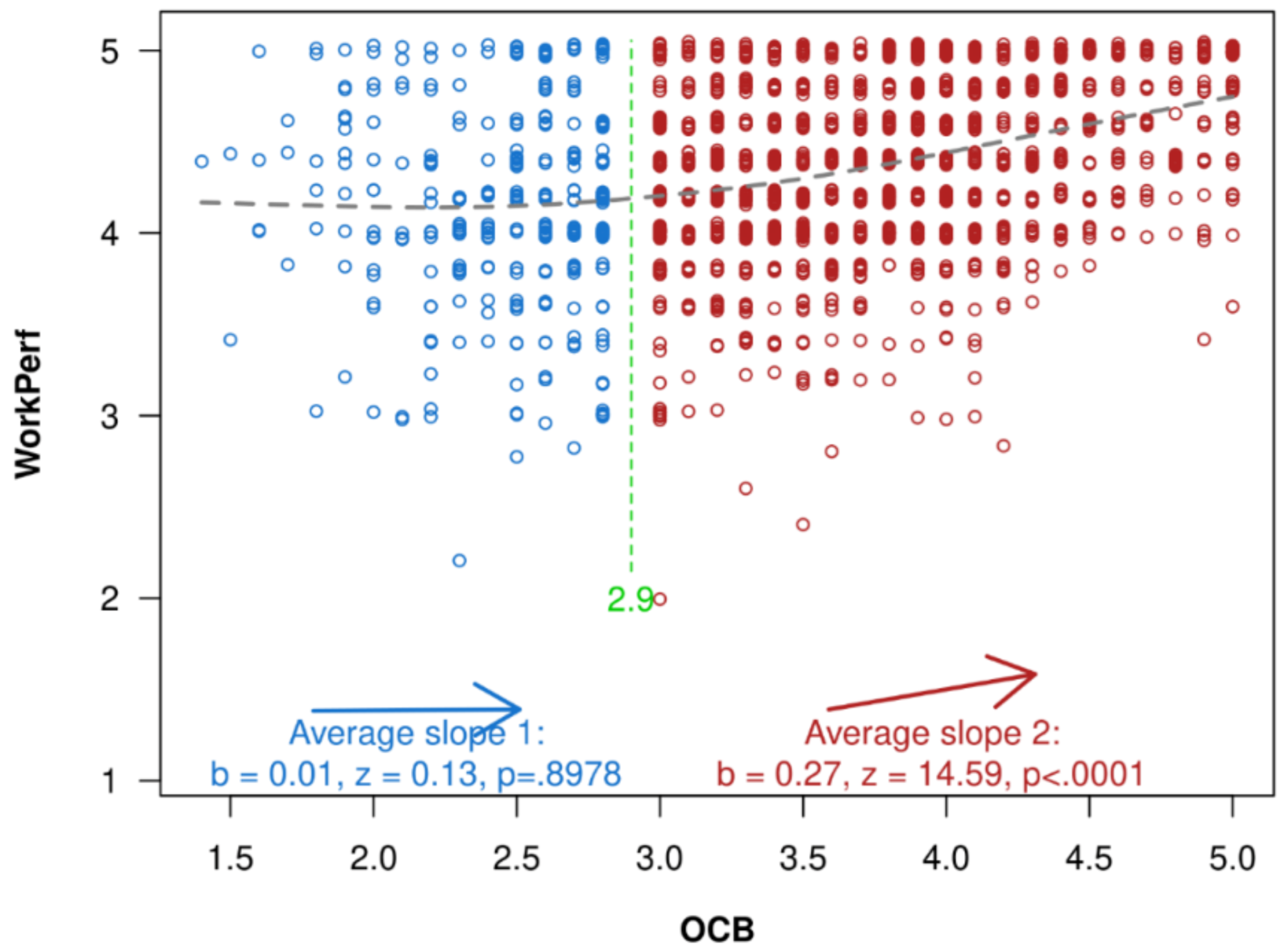

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oplatka, I. Going beyond role expectations: Toward an understanding of the determinants and components of teacher organizational citizenship behavior. Educ. Adm. Q. 2006, 42, 385–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogler, R.; Somech, A. Psychological capital, team resources and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Psychol. 2019, 153, 784–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göktürk, Ş. Assessment of the quality of an organizational citizenship behavior instrument. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2011, 22, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.; Kong, D.T.; Kim, K.Y. Social support at work: An integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 42, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Klotz, A.C.; Turnley, W.H.; Harvey, J. Exploring the dark side of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: Recent trends and developments. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 80, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Blair, C.A.; Meriac, J.P.; Woehr, D.J. Expanding the criterion domain? A quantitative review of the OCB literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzmuller, M.; Van Dyne, L.; Ilies, R. Organizational citizenship behavior: A review and extension of its nomological network. SAGE Handb. Organ. Behav. 2008, 1, 106–123. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Schwartz, B. Too much of a good thing: The challenge and opportunity of the inverted U. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pierce, J.R.; Aguinis, H. The too-much-of-a-good-thing effect in management. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H.; Bloodgood, J.M. Citizenship behavior and the creation of social capital in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; De-Pablos-Heredero, M. The paradox of citizenship cost: Examining a longitudinal indirect effect of altruistic citizenship behavior on work–family conflict through coworker support. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 661715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, E.S. Reciprocity reconsidered: Gouldner’s moral norm of reciprocity and social support. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1995, 12, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovsky, M.A.; Pugh, S.D. Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, B.J.; Scott, B.A. Integrating social exchange and affective explanations for the receipt of help and harm: A social network approach. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2012, 117, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Blume, B.D. Individual-and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Somech, A.; Bogler, R. The pressure to go above and beyond the call of duty: Understanding the phenomenon of citizenship pressure among teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 83, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H. The personal costs of citizenship behavior: The relationship between individual initiative and role overload, job stress, and work-family conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergeron, D.M. The potential paradox of organizational citizenship behavior: Good citizens at what cost? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1078–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, E.M.; Chang, C.H.; Miloslavic, S.A.; Johnson, R.E. Relationships of role stressors with organizational citizenship behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, A.M. Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, K.; Allen, N.J. Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.M. Distinguishing contextual performance from task performance for managerial jobs. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Hofmann, D.A. Role expansion as a persuasion process: The interpersonal influence dynamics of role redefinition. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 1, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, G.W.; Brunstein, J.C. The role of personal work goals in newcomers’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment: A longitudinal analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, J.; Lanaj, K.; Scott, B.A. Integrating the bright and dark sides of OCB: A daily investigation of the benefits and costs of helping others. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Barnard, S.; Rush, M.C.; Russell, J.E. Ratings of organizational citizenship behavior: Does the source make a difference? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2000, 10, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I.S.; Berry, C.M. The five-factor model of personality and managerial performance: Validity gains through the use of 360 degree performance ratings. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Bowler, W.M. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors and Burnout. In Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Review of “Good Soldier” Activity in Organizations; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, R.; Dimotakis, N.; De Pater, I.E. Psychological and physiological reactions to high workloads: Implications for well-being. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 63, 407–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, J.R.; House, R.J.; Lirtzman, S.I. Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1970, 15, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Eurostat: Women Teachers Largely Over-Represented in Primary Education in the EU. Available online: https://skillspanorama.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news/eurostat-women-teachers-largely-over-represented-primary-education-eu (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Spector, P.E.; Bauer, J.A.; Fox, S. Measurement artifacts in the assessment of counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: Do we know what we think we know? J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, N.C.; Berry, C.M.; Houston, L. A meta-analytic comparison of self-reported and other-reported organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, V.; Aubé, C. Team self-managing behaviors and team effectiveness: The moderating effect of task routineness. Group Organ. Manag. 2010, 35, 751–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, C.G.; Zhou, Q.; Ferreira, A.I. The impact of anger on creative process engagement: The role of social contexts. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munc, A.; Eschleman, K.; Donnelly, J. The importance of provision and utilization of supervisor support. Stress Health 2017, 33, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, A.L.; Leppänen, A.; Jahkola, A. Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2003, 29, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolan, E.D.; Mohr, D.; Lempa, M.; Joos, S.; Fihn, S.D.; Nelson, K.M.; Helfrich, C.D. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometric evaluation. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F.; Cai, L. Using heteroskedasticity-consistent standard error estimators in OLS regression: An introduction and software implementation. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simonsohn, U. Two lines: A valid alternative to the invalid testing of U-shaped relationships with quadratic regressions. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 1, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2010, 45, 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidemeier, H.; Moser, K. Self–other agreement in job performance ratings: A meta-analytic test of a process model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.M.; Huffcutt, A.I. Psychometric properties of multisource performance ratings: A meta-analysis of subordinate, supervisor, peer, and self-ratings. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 331–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.G.; Muijs, D. School Leadership Effectiveness: The Growing Insight in the Importance of School Leadership for the Quality and Development of Schools and Their Pupils. In School Leadership-International Perspectives; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nguni, S.; Sleegers, P.; Denessen, E. Transformational and transactional leadership effects on teachers’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior in primary schools: The Tanzanian case. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2006, 17, 145–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Leithwood, K. Direction-setting school leadership practices: A meta-analytical review of evidence about their influence. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2015, 26, 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taun, K.; Zagalaz-Sánchez, M.; Chacón-Cuberos, R. Management skills and styles of school principals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, T.; Sikström, P.; Jääskelä, P.; Korkala, S.; Kotkajuuri, J.; Kaski, S.; Taalas, P. Factors constraining teachers’ wellbeing and agency in a Finnish university: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amotz, R.; Green, G.; Joseph, G.; Levi, S.; Manor, N.; Ng, K.; Barak, S.; Hutzler, Y.; Tesler, R. Remote teaching, self-resilience, stress, professional efficacy, and subjective health among Israeli PE teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, S.; Shirom, A.; Fried, Y.; Cooper, C. A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 227–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boswell, W.R.; Olson-Buchanan, J.B.; LePine, M.A. The relationship between work-related stress and work outcomes: The role of felt challenge and psychological strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, M.A. A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.89 | 0.31 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 42.72 | 9.6 | −0.061 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Work tenure | 17.23 | 10.43 | 0.042 * | 0.773 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 4. OCB | 3.58 | 0.69 | 0.044 * | 0.065 ** | 0.082 ** | 1 | |||||

| 5. OCB-Org | 3.59 | 0.74 | 0.038 | 0.084 ** | 0.090 ** | 0.928 ** | 1 | ||||

| 6. OCB-Ind | 3.56 | 0.75 | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.063 ** | 0.929 ** | 0.723 ** | 1 | |||

| 7. Workload | 5.69 | 1.34 | 0.055 * | 0.087 ** | 0.092 ** | 0.200 ** | 0.213 ** | 0.161 ** | 1 | ||

| 8. Social support | 5.53 | 1.41 | 0.016 | −0.172 ** | −0.169 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.112 ** | 0.173 ** | −0.018 | 1 | |

| 9. Work performance | 4.35 | 0.48 | 0.018 | 0.054 * | 0.046 * | 0.320 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.292 ** | 0.012 | 0.176 ** | 1 |

| 10. MWRO | 2.42 | 1.00 | 0.062 ** | 0.009 | 0.027 | −0.100 ** | −0.090 ** | −0.097 ** | 0.073 ** | −0.280 ** | −0.281 ** |

| Variables | Work Performance | MWRO | Mediators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Workload | Social Support | |

| Constant | 3.46 ***(0.08) | 3.29 *** (0.09) | 2.78 *** (0.17) | 3.57 *** (0.20) | 3.80 *** (0.30) | 5.11 *** (0.23) |

| Gender | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.19 **(0.07) | 0.16 * (0.07) | 0.23 * (0.10) | 0.03 (0.10) |

| Age | 0.002 (0.002) | −0.002 † (0.002) | −0.003 (0.004) | −0.003 (0.004) | 0.01 (0.005) | −0.01 ** (0.01) |

| Work tenure (WT) | −0.001 (0.002) | 0.00 (0.002) | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.0002 (0.003) | 0.01 (0.005) | −0.02 **(0.005) |

| OCB-Org | 0.12 *** (0.02) | 0.12 *** (0.02) | −0.06 (0.04) | −0.08 * (0.04) | 0.33 *** (0.05) | −0.001 (0.06) |

| OCB-Ind | 0.10 *** (0.02) | 0.09 *** (0.02) | −0.09 * (0.04) | −0.03 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.35 *** (0.06) |

| Workload | −0.02 ** (0.01) | 0.07 ***(0.02) | ||||

| Social support | 0.05 *** (0.01) | −0.20 ***(0.02) | ||||

| N | 2170 | 2170 | 2170 | 2170 | 2170 | 2202 |

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| F change | 49.26 *** | 27.79 *** | 6.65 *** | 99.33 *** | 23.13 *** | 29.82 *** |

| Variables | OCB Total | OCB Low Scores | OCB High Scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workload | Social Support | Workload | Social Support | Workload | Social Support | |

| Constant | 3.78 ***(0.23) | 5.14 *** (0.24) | 3.71 *** (0.35) | 5.62 *** (0.38) | 3.72 ** (0.60) | 4.80 ** (0.56) |

| Gender | 0.23 * (0.11) | 0.003 (0.10) | 0.35 **(0.12) | 0.01 (0.13) | 0.05 (0.19) | 0.06 (0.16) |

| Age | −0.01 (0.005) | −0.01 ** (0.005) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 * (0.01) | 0.004 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.01) |

| Work tenure (WT) | 0.01 (0.005) | −0.02 *** (0.005) | −0.004 (0.006) | −0.02 ** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 † (0.01) |

| OCB | 0.37 *** (0.04) | 0.34 *** (0.04) | 0.34 *** (0.09) | 0.22 *(0.09) | 0.44 *** (0.13) | 0.37 ** (0.12) |

| N | 2170 | 2170 | 1121 | 1121 | 1049 | 1049 |

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| F statistic | 26.87 *** | 32.97 *** | 9.21 *** | 15.26 *** | 4.30 ** | 9.62 *** |

| Variables | OCB Total | OCB Low Scores | OCB High Scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Performance | MWRO | Work Performance | MWRO | Work Performance | MWRO | |

| Constant | 3.29 ***(0.09) | 3.57 *** (0.20) | 3.62 *** (0.15) | 3.23 *** (0.31) | 2.97 ** (0.17) | 4.38 ** (0.43) |

| Gender | −0.03 (0.03) | 0.16 * (0.07) | 0.03 (0.05) | −0.16 † (0.08) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.19 † (0.10) |

| Age | 0.003 † (0.002) | −0.003 (0.004) | 0.001 (0.002) | −0.003 * (0.005) | 0.004 † (0.002) | −0.003 (0.01) |

| Work tenure (WT) | −0.0001 (0.002) | 0.0003 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.002) | −0.002 † (0.004) | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.0001 (0.005) |

| OCB | 0.21 *** (0.02) | −0.11 *** (0.03) | 0.08 * (0.03) | 0.09 (0.06) | 0.31 *** (0.03) | −0.38 *** (0.09) |

| Workload | −0.02 * (0.01) | 0.06 *** (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.02) | −0.02 ** (0.01) | 0.10 *** (0.02) |

| Social support | −0.05 *** (0.01) | −0.20 *** (0.02) | 0.06 *** (0.01) | −0.21 ***(0.02) | 0.04 **(0.01) | −0.19 *** (0.03) |

| N | 2170 | 2170 | 1121 | 1121 | 1049 | 1049 |

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| F statistic | 49.79 *** | 35.95 *** | 6.50 *** | 17.47 *** | 19.90 *** | 21.07 *** |

| Variables | Work Performance | Maladaptive Work-Related Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCB Scores | Mediator | Indirect Effect (SE) | Confidence Interval | Indirect Effect (SE) | Confidence Interval |

| OCB total | Social support | 0.02 (0.003) | [0.01; 0.03] | −0.07 (0.01) | [−0.09; −0.05] |

| Workload | −0.01 (0.003) | [−0.01; −0.002] | 0.02 (0.01) | [0.01; 0.04] | |

| OCB low scores | Social support | 0.01 (0.01) | [0.002; 0.03] | −0.05 (0.02) | [−00.9; −00.01] |

| Workload | −0.005 (0.005) | [−0.01; 0.003] | 0.01 (0.01) | [−0.01; 0.03] | |

| OCB high scores | Social support | 0.01 (0.01) | [0.004; 0.02] | −0.07 (0.02) | [−0.12; −0.03] |

| Workload | −0.01 (0.005) | [−0.02; −0.002] | 0.04 (0.02) | [0.02; 0.08] | |

| OCB Org | Social support | −0.005 (0.003) | [−0.01; 0.01] | 0.002 (0.01) | [−0.02; 0.03] |

| Workload | −0.01 (0.003) | [−0.01; −0.001] | 0.02 (0.01) | [0.01; 0.04] | |

| OCB Ind | Social support | 0.02 (0.004) | [0.01; 0.03] | −0.07 (0.01) | [−0.10; −0.05] |

| Workload | −0.001 (0.001) | [−0.003; 0.001] | 0.003 (0.004) | [−0.004; 0.01] | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muntean, A.F.; Curșeu, P.L.; Tucaliuc, M. A Social Support and Resource Drain Exploration of the Bright and Dark Sides of Teachers’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120895

Muntean AF, Curșeu PL, Tucaliuc M. A Social Support and Resource Drain Exploration of the Bright and Dark Sides of Teachers’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(12):895. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120895

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuntean, Arcadius Florin, Petru Lucian Curșeu, and Mihai Tucaliuc. 2022. "A Social Support and Resource Drain Exploration of the Bright and Dark Sides of Teachers’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors" Education Sciences 12, no. 12: 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120895

APA StyleMuntean, A. F., Curșeu, P. L., & Tucaliuc, M. (2022). A Social Support and Resource Drain Exploration of the Bright and Dark Sides of Teachers’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Education Sciences, 12(12), 895. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120895