Abstract

This study investigates the role of emotions in second language learning, in particular, that of anxiety. Research has shown that positive and negative emotions are interrelated and that negative emotions are negatively correlated with motivation. It is, therefore, important to investigate how learners regulate their emotions. In this case study, one learner was closely observed over a period of 13 years. This learner claims that he has been feeling strong anxiety while learning English, but also that his negative emotion was the source of motivation to proactively study the language. The research used three types of data: (a) language learning historical records, (b) in-depth interviews, and (c) two questionnaires: the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale and the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning questionnaire. The results reveal the intense experience of the learner’s emotions, as well as the significant shifts therein. It also unearths some of the sources of his emotional experiences and how he regulated these experiences. An important observation was the positive contribution that negative emotions had on some aspects of the participant’s learning.

1. Introduction

Research has shown higher levels of language anxiety to be correlated with lower levels of language learning [1]. The learner investigated in this study has been showing a high level of anxiety since he started learning English at an early age. He began taking English conversation classes from the age of five and compulsory English classes at school from the age of six. He also participated in two international student exchange programs to Australia and the US. Even though he has approximately 13 years of learning experience, he experiences strong negative emotions, especially when speaking.

The purpose of this study is two-fold. The first aim of the study is to understand how the learner experienced anxiety towards his second language learning during the 13 years. The second aim is to investigate the strategies he used to regulate his anxiety. Although there is a body of research that has documented the negative impact of anxiety on language learning, very few studies have investigated how learners regulate this. In addition, few studies have taken an approach to analyze a learning experience over a long period of time. We aim to fill these gaps with the present study.

1.1. Literature Review

Language anxiety is defined as “feelings of worry and negative, fear-related emotions with learning or using a second language” [1]. Anxiety is the most widely studied emotion in SLA, due to its intensity and frequency [2]. According to a study by Méndez López et al. [3], language anxiety was the most common negative emotion experienced by students during English study. Much of the prior research has identified speaking as a major source of anxiety [4], with Woodrow’s study [5] showing 85% of respondents claiming to experience L2 speaking anxiety. The study by Said and Weda [6] also shows strong correlation between English language learning anxiety and students’ oral communication. However, it has been found that there are significant cultural differences in how anxiety is experienced. For example, in countries with strict social norms, the inability to ‘follow the rules’ causes anxiety [7]. In a country like Japan (the setting for this study), the cultural norm of not standing out from others makes learners feel anxious to speak the language [8]. Foreign language anxiety of Japanese learners is suggested to stem from poor academic achievement, reduced self-confidence, and cognition issues [9]. In their study of university students in Japan, Kondo and Yang [10] found three factors associated with English language classroom anxiety: low proficiency in English, evaluation by peers, and oral production activities. Imada’s study [11] investigated the equivalents of anxiety (‘fu-an’ in Japanese), fear (‘kyo-fu’), and depression (‘yu-utsu’). He found that connotations of anxiety are different between American and Japanese students. In Japanese, the similarity of ‘fu-an’ (anxiety) with ‘yu-utsu’ (depression) is greater than that with ‘kyo-fu’ (fear). On the contrary, in English, anxiety is more similar to fear than depression. Americans’ descriptions of the experience of anxiety refers to not being able to achieve one’s goals, while Japanese often perceive the experience to be an uneasy expectancy of losing peace and comfort.

Either way, anxiety is not a static phenomenon. It is subject to, amongst others, teachers’ actions, such as creating a comfortable classroom environment, and being understanding of learners’ emotions [12]. An increasing recognition in recent years points towards the importance of the situated and changing nature of emotions in language learning. The Dynamic Approach [13] identifies that anxiety fluctuates over time and continuously interacts with many factors, such as other learners, linguistic abilities, physiological responses, self-appraisals, interpersonal relationships, and the environment. Anxiety in this view is situation-specific and fluctuates on a momentary basis. It is also acknowledged that learners have some control over their experience of the emotion.

1.2. Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation is the process by which people attempt to change their existing emotion to a desired one [14]. People regulate their emotions driven by their motives: people try to maximize pleasure and minimize pain, desire tangible consequences, and want to experience emotions to alter behavior in a desirable manner. Emotion regulation is the activation of a goal to influence the emotion trajectory [15]. This goal itself may sometimes be the desired end point. People change the intensity of the emotion either by controlling the degree of the emotion experienced or by changing their behavior. People change the duration of the emotion by controlling how long an emotion continues and change the quality of an emotional response. To achieve these goals, people use emotion regulation strategies. Strategies are activities consciously chosen by learners for the purpose of regulating their own language learning [16]. The definitions by Oxford [17] emphasizes dynamism and flexibility:

L2 learning strategies are complex, dynamic thoughts and actions, selected and used by learners with some degree of consciousness in specific contexts in order to regulate multiple aspects of themselves (such as cognitive, emotional, and social) for the purpose of (a) accomplishing language tasks; (b) improving language performance or use; and/or (c) enhancing long-term proficiency. Strategies are mentally guided but may also have physical and therefore observable manifestations. Learners often use strategies flexibly and creatively; combine them in various ways, such as strategy clusters or strategy chains; and orchestrate them to meeting learning needs.(p. 48)

Oxford [18] developed a taxonomy for categorizing strategies under six headings: (a) cognitive strategies that enable the learner to manipulate the language material in direct ways, (b) metacognitive strategies employed for managing the learning process overall, (c) memory-related strategies that help learners link one L2 item or concept with another but do not necessarily involve deep understanding, (d) compensatory strategies that help the learner make up for missing knowledge, (e) affective strategies, such as talking about feelings, and (f) social strategies that help the learner work with others and understand the target culture.

Several studies have shown positive correlations between strategy use and successful language learning. There is a need for a richer description of language learning strategy use, which can be achieved by using more qualitative methods in addition to administering questionnaires. Oxford [17] emphasizes the value of student narratives for understanding learners’ strategies, for example their own stories of learning in specific sociocultural environment, specific learning challenges, and episodes on their emotions when learning.

Bown and White’s study [19] presents cases on how integral the regulation of affect was to learning experiences. Emotion is important in the learner’s social relationship, for instance developing good relationships with instructors. For example, a learner who had an unhelpful instructor managed to position the instructors differently by having them cooperate to construct what the learner was trying to say. The students used both cognitive and metacognitive strategies to regulate emotions focusing on learner-initiated processes and strategies that encouraged achievement. Another learner regulated his feelings by focusing on his study and schedule. He managed his anxiety by planning and organizing his language learning.

Rose and Harbon [20] demonstrated that visualizing progress in performance affects emotional control in the learning of kanji (Japanese written characters). In their study, the beginner level students studying kanji with weekly assessments were able to clearly see their progression, which motivated their learning. However, for students at the higher-proficiency level who no longer had formal training or review, the learning task was daunting and led to boredom, and they tended to lose their ability to self-regulate. They got frustrated as they felt a lack of progress, which led to a negative impact on their learning.

In a recent study, Benita et al. [21] indicate how a motivating context makes a difference in emotion regulation. When comparing the participants in autonomy-supportive contexts with controlling contexts, when they chose whether to continue to regulate their emotions or not, the former persevere more than the latter. This suggests that those in autonomy-supportive contexts had internalized the emotion goal and sustained goal pursuit.

A growth mindset [22] is the belief that intelligence is not simply fixed but can be shaped and developed. If learners believe that their language ability can be improved, then they are more likely to persist in the activity. In contrast, if they have a fixed mindset, validating their ability becomes important and obstacles are more easily attributed to low ability. To successfully engage with language learning opportunities in the long term, learners need to believe that their competence and abilities can be enhanced.

1.3. Implications for the Present Study

As emotions are dynamic, it is necessary to analyze them by integrating other interconnected variables, such as language proficiency development, changes in learning goals, and learners’ self-efficacy, amongst others [23]. Language anxiety is personal, individual, and is different for each respondent. However, traditional research methods are often non-dynamic, and provide only a snapshot of what was occurring at the time when the variable was being measured. The present study uses a modified case study approach of a respondent who is the researcher’s son, therefore, the data can be analyzed incorporating the learning history and language development over a period of 13 years. By using multiple instruments, including an in-depth interview, we were able to investigate the learner’s emotions in-depth.

Our research questions were:

- How did the learner experience anxiety during his 13 years of language learning?

- How did he regulate his anxiety?

2. Methodology

2.1. Theoretical Framework

In this study, we adopt Gregerson’s Dynamic Approach to the investigation of language learner anxiety. Anxiety is considered to be an emotion that fluctuates over time, and continuously interacts with situational factors, for example the learner’s changing linguistic abilities, his physiological reactions, self-related appraisals, the types of settings in which the learning occurs, etc. [2].

2.2. The Subject of the Study

The respondent is a 17-year-old male Japanese speaker, named Taiga. He is the first author’s son. In addition to his compulsory English classes from the age of six, once a week at primary school, and five classes a week at secondary school, he attended an English conversation class with a native speaker once a week for almost 10 years starting at the age of six. He also joined in two international exchange visits at the ages of 10 and 14, for two weeks each time.

Approval for the research was given by the Chair of the Anaheim University ethics committee. Participation by the learner was voluntary and great care was taken to remind him of his right to withdraw at any time while creating a comfortable atmosphere during the data collection.

2.3. Instruments

Data were collected through (a) two types of questionnaires, followed by (b) an in-depth interview. The first questionnaire was the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety (FLCAS) survey, investigating physical symptoms of anxiety, nervousness, and lack of confidence. It is a 33-item questionnaire developed by Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope in 1986 and has been widely validated [24]. For this study, this questionnaire was administered in two stages. For the first placement, eight items were extracted from the FLCAS reflecting physical symptoms of anxiety, nervousness, and lack of confidence [24,25]. Four months later, the entire FLCAS instrument with all of its 33 items was administered. This was followed by the second interview.

The second questionnaire was the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) developed by Oxford [26] to assess the specific language learning strategies employed by students in learning a foreign language. It consists of 80 items from six categories: memory, cognitive, compensation, metacognitive, affective, and social strategies. A short version consisting of 50 items developed for students by Oxford [26] was administered for this study. This too has been widely used and validated.

The primary purpose for the questionnaires was to obtain an overview of the learner’s attitudes towards language learning, the type and amount of anxiety experienced, and key learning strategies used in its regulation.

Two in-depth interviews were held with the participant. Both interviews targeted the anxiety experienced in learning the language, such as intensity, frequency, and the nature of the feeling, the first focusing on his previous experiences and the second on his current experiences. Another focus was on the strategies used to overcome anxiety, whether any other strategies were deemed to be useful to manage his emotions. The interviews were done in an open-ended manner to obtain in-depth insights and referred to the results from the questionnaires administered beforehand and the record of his learning history maintained by the first author to assist the respondent to recollect his past experiences. The first interview focused on the respondent’s current learning experience, while in the second interview, we asked about the experiences in his early years. The interviews lasted just over one hour each and were recorded, transcribed, and translated verbatim from Japanese to English.

2.4. Procedures

A translated version of the two questionnaires was prepared by the first author. The translations were reviewed by two additional Japanese English instructors to confirm the translations were correct and easy to understand.

The FLCAS eight-item-questionnaire was administered first on 20 March 2020, followed by the SILL questionnaire: 29 items on memory, cognitive, and compensation strategies on 21 March 2020, and 21 items on metacognitive, affective, and social strategies on 22 March 2020.

The interview was conducted following the questionnaires. Several interview questions were prepared, and these included:

- (a)

- What are the learner’s experiences in language learning?

- (b)

- What occasions cause greater anxiety?

- (c)

- What strategies does he use to overcome his anxiety?

- (d)

- Among the strategies listed in the questionnaire (SILL), which ones does he think are effective for his learning, and why?

The interviews took place at the first author’s home and was conducted by the first author in Japanese.

An interview guide (see Appendix C) was developed for the following two reasons. First, to ascertain that the interview would enable us to obtain necessary information by confirming the probing points listed in the guideline. Another reason for developing an interview guide was to avoid subjectivity by having the respondent attend the interview seriously and understand the importance of his comments. As the interview–interviewee relationship was one of mother and son, there was a risk of the respondent not talking earnestly or not elaborating enough by assuming that the mother knew what he was trying to say. An interview guide in front of the interviewer offered a sense of formality for both. In addition, the guide allowed the second author to review the interviews independently to ensure all main points were addressed. An interview practice was held between the two authors to confirm the flow, and a pilot interview was conducted with a nineteen-year-old learner to fine-tune the flow to allow enough time to recall the experiences the learner had.

The dates of the questionnaires and interviews placed are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dates for questionnaire and interview placement.

2.5. Data Analysis and Synthesis

The analysis involved (a) finding key themes regarding the learner’s experience of anxiety and (b) analyzing how emotion regulation was carried out to overcome anxiety.

2.6. Questionnaire

Data obtained from the questionnaires was entered into a spreadsheet and descriptive statistics were calculated. The findings were then used to guide the interviews.

2.7. Interview

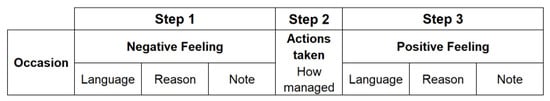

The interview data was transcribed and analyzed, focusing on the causes of anxiety and the learner’s self-regulation. First, the interview was transcribed and next, a list of key words was developed, and the words were summarized in the following format (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Format used to summarize the verbatim.

2.7.1. Step 1: Negative Feeling by Occasion

The key words were listed by occasion in which he experiences negative emotion: i.e., when speaking in front of class, when speaking with a native teacher, etc. For each occasion, the language used to express the negative feeling was listed along with the reasons for those feelings and notes on other features that accompanied those feelings (i.e., physical reactions).

2.7.2. Step 2: Actions Taken

For each negative feeling, the actions taken to overcome the feeling were listed (i.e., practice what to present during pair work, try to find easy words).

2.7.3. Step 3: Positive Feeling as a Result of an Action Taken Above

This list of verbatim comments related to positive feelings including the action that was taken at step two above were listed: the language used to express the feeling, the reasons for the feeling, and noted was any additional information related to the emotion.

Based on the verbatim summary above, the emotions were reorganized as the sequence of how the learner’s emotion regulation brought the negative feeling to a positive (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Format showing the sequence of emotion.

It is necessary to analyze the emotion in sequence, from negative to positive, but not as separate feelings. In the process model of emotion regulation, emotion generation is sequentially described as encountering relevant situations, attending to key aspects of those situations, appraising the situations in relation to active goals, and having experimental, physiological, and/or behavioral responses [27]. Analyzing the sequence of these emotions should indicate how the emotion shifts from negative to positive.

To avoid subjectivity issues, and following Nunan and Bailey [28], intercoder agreement was reached by the two authors through joint development of the coding list and reaching consensus on the codes. Expressions of emotions were highlighted and contextual variables (e.g., location, interlocutors, etc.) were identified. Finally, expressions of self-regulation were identified. A sample of approximately 20% of the transcript was independently coded by the second researcher and only a small number of discrepancies were identified and discussed until consensus was reached.

3. Results

This section will present the findings of the study’s two research questions in two separate sections: (1) How did the learner experience anxiety during his 13 years of language learning? and (2) How did he regulate his anxiety?

3.1. Experiences of Anxiety

During the interview, Taiga was asked to recall his classes and events related to English learning and his experiences of anxiety at the time. In the early days, at elementary school (ages 6–8), the main cause of his anxiety was having to present in front of people, especially when he was unsure about his ability. He recalls having to read out loud from the textbook and feeling insecure about this, even in a small group. This was especially the case when the sentences included long words he did not understand. Reading incomprehensible words out loud made him feel incompetent. When he was 10 years old, he traveled to Australia to stay with Michael and his family. Michael, who was 12 years old at the time, had visited Japan the year before to spend two weeks with Taiga’s family and the two boys, therefore, knew each other quite well. However, Taiga was not confident in speaking English before traveling to Australia. Moreover, during his stay in Australia, he was nervous as he did not understand what people were saying.

Regarding Taiga’s anxiety for the more recent years (age 14–17), there are two sets of data: the FLCAS questionnaire and the first interview, focusing on his current learning experiences. Appendix A shows the results from the FLCAS questionnaire consisting of 33 questions relating to anxiety in English learning.

Three causes for his anxiety emerged: (a) he feels extremely nervous when speaking in front of the class in fear of being judged negatively; (b) he experiences intense emotions when speaking without preparation due to his low confidence in expressing his opinion in English; and (c) he has a strong fear of pauses, which he believes to be an indication of low language ability.

3.1.1. Speaking in Front of the Class

The FLCAS results in Table 2 show that Taiga continues to have strong anxiety towards speaking in front of people, such as in class. For the two statements relating to speaking in front of the language class, Taiga gives the highest agreement ratings, “I start to panic when I have to speak without preparation in language class (4)”, and disagrees with the statement, “I feel confident when I speak in foreign language class” (2).

Table 2.

Results from FLCAS questionnaire.

In the interview, Taiga explains that he does not like making presentations in pairs in front of the teacher for fear of making errors. He feels uncomfortable and uneasy as he worries about his partner’s evaluation of his performance. He gets extremely nervous when making a formal presentation as he worries that his mind may go blank.

During the interview he showed the level of his emotions using such identifiers as “I definitely [emphasis added] get nervous”, “I get extremely [emphasis added] nervous”, although he rarely uses such language in daily life. He elaborates on the strong intensity of this feeling by giving examples of his physical reaction when in such situations, as shown in the following excerpt:

Interviewer (I): In terms of English language learning, in which occasion are you severely nervous?

Taiga (T): I hate to speak in front of people…When you make a speech, I definitely get nervous. If anybody says something different, everybody makes fun of him….I get extremely nervous. I have a pounding heartbeat, my breath becomes shallow. Always, always. Topic doesn’t matter.

3.1.2. Nominated to Speak without Preparation

In the interview, Taiga showed his experiences of negative feelings when answering to the native instructor’s questions. He mentioned his low confidence in expressing an opinion in English, particularly without preparation. His first reaction when nominated by the instructor is that he feels like “It’s ‘The end.’” He explains in the following excerpt:

T: I don’t want to speak in the class by native speaking teachers. It’s because I can’t do the English composition. I can’t express what I want to say.

I: What do you do?

T: I just think, “It’s ‘The end’ [emphasis added] if the teacher nominates me”…We usually don’t have any preparation time. He gives us a topic on the spot, and we have to manage it impromptu.

3.1.3. Pauses during Conversation

Taiga described his response to pauses as one of strong fear and said “he cannot tolerate” such moments because it indicates a low level of comprehension. He also hesitates to ask the native instructor to repeat the question because the teacher may assume that the student is not seriously listening to the instruction. Taiga’s fear of pauses is so strong that he expresses his feelings by using strong language, saying “It’s over” when in such a situation, as he explains in the following excerpt.

T: I can’t tolerate that awkward, embarrassed silence or atmosphere. There are some classmates who react like, “Don’t you understand such an easy question?”…If I don’t understand what the native speaking teacher said, “it’s over” or “I have to give up”. It’s because I don’t want to ask him to repeat over and over again…If I say, “Pardon me?” so many times, it would upset him.

3.2. Regulating Anxiety

As the experience of anxiety has changed over the years, Taiga’s regulation of negative emotions has also changed. In his early years, he describes how, although he hesitated to read out texts he did not fully understand, he remembers that the material’s pictures were fun, and the instructions by the teacher motivated him to participate in a presentation contest, as shown in the excerpt.

T: I memorized the story “The Magic Tree”. I tried hard to memorize them. I always went to Mr. Moritch’s room to practice for the presentation during lunch break… I thought that I only had to pronounce the same way as Mr. Moritch did…..I think I could speak English very well at that time.

The use of visual cues and memorization helped him at this time.

Another major stage in his studies was his preparation, at the age of nine, for his exchange program with Michael’s family in Australia. He studied hard because he believed that not being able to speak English would make him feel anxious. He developed his own strategy to learn in chunks instead of words, and he found that reviewing everyday was essential for long-term memory. He explains in the following excerpt:

T: Even though I master lots of vocabulary, I can’t hear when they are in a sentence. So I needed to memorize in chunks. For example, the words “like [laik]” and “cat [kæt]” sound completely different when they are in a sentence, “I like cats [ailai kæts].”…..It usually takes about 5 to 6 times or days to completely memorize them. I read out loud the English words, checking visually the Japanese translation. I did this every day to master them until I traveled to Australia.

After entering high school, his emotion regulation involved three broad strategies: (1) search for effective ways to meet the goal, (2) focus on the strategy that maximize his vast amount of vocabulary, and (3) to think in a positive way by recalling successful experiences.

In describing these results, we draw on his responses to the two questionnaires and the interview. The full results from the FLCAS and SILL questionnaires are in Appendix A and Appendix B.

3.2.1. Searching for Effective Ways to Learn

In the interview, Taiga identified his large vocabulary as a strength. He had been reviewing vocabulary on a daily basis for over two years and enjoyed the sense of achievement he gained from this. He also used his vocabulary knowledge as a way to minimize his anxiety by feeling more in control over his speaking, as he could rely on his existing knowledge. The results of the SILL showed that he reports “having clear goals for improving my SL skills”, “I plan my schedule so I will have enough time to study SL”, and “I notice my SL mistakes and use that information to help me do better”.

These metacognitive strategies helped him to achieve a sense of efficiency and enjoyment as in the following excerpt:

T: I read through this 3500-word textbook, 5 chapters a day…so it means 350 words a day…if I work on this every day, I can study the whole book in 10 days. It means that I can review all the words 36.5 times a year. If I can come up with its meaning in Japanese at the moment I see the English word that means OK. I’m OK if I can recall exactly the same Japanese translation.

Taiga also works on tasks following a scientific process. He uses cognitive strategies such as reviewing vocabulary following the forgetting curve developed by Ebbinghaus [29], as he believes that he can maximize the retention rate of the newly learned words. On SILL, he reports to “say or write new SL words several times”, “look for words in my own language that are similar to new words in SL”, “try find patterns in SL” and “find the meaning of an SL word by dividing it into parts that I understand”.

Taiga designed learning tasks or materials to achieve a sense of efficiency and enjoyment, such as creating an original memory notebook. In the notebook, he writes down new vocabulary or idioms presented in other sources. At the same time, he enjoys making a hand-made memory notebook as mentioned in the excerpt:

T: I’m not learning only from that vocabulary textbook, but also making my own memory notebook. If there are any unknown words when reading passages, I write it down in my notebook…and memorize them before going to bed. All students use that vocabulary textbook, so you cannot win by just learning the words in it.

To pursue efficiency in learning, the social strategy of “practicing with his partner before presentation” may also include some enjoyable elements of talking with his friend. He also believes tests, including formal examinations, to be a “game”, as he talks about in this excerpt:

T: For me, a reading test is a “word game [emphasis added]”. The level of my understanding of the passage depends on the number of words I am familiar with. Therefore, it is a game to try myself.

3.2.2. Think in a Positive Way by Recalling Good Experiences

Although Taiga experiences anxiety in speaking, right at the moment when he has to begin to speak, he regulates his emotion to think in a positive way. His past positive experiences encourage him to use this strategy of self-regulation. For example, he remembers that his instructor always understands what he says, as in the excerpt:

T: I think I can manage it as I have never had any problem listening to what native instructor says. I try to give my opinion by using simple, easy words and structures, and then he always understands what I am trying to say. I can do it because I know lots of vocabulary.

Taiga also uses the social strategy of practicing with a partner to organize his thinking and to find the words he should use, which leads him to feel confident.

T: …we present in front of the class what we have discussed in pairs…. In case nominated by the instructor, I simply say what I practiced with my partner, then the teacher understands me. So I am all right, no problem.

3.2.3. Focus on the Strategy That Maximizes His Vast Amount of Vocabulary

Taiga has strong fear of pauses or silence as he believes that it indicates a low level of comprehension or not seriously listening to the speaker. To minimize this pausing and keep the conversation flowing, he focuses on using compensation strategies as reported in SILL, “I make up new words if I do not know the right ones in the SL”, “If I can’t think of an SL word, I use a word or phrase that means the same thing”, and “To understand unfamiliar SL words, I make guesses”. He instantly seeks for easy words to convey his idea.

T: I try to give my opinion by using simple, easy words and structures….if I cannot come up with the word “observe”, I say “see” instead. I do this because I always feel uncomfortable and uneasy when there is a long silence, so I try to find easy words. I can manage it because I’ve mastered lots of vocabulary.

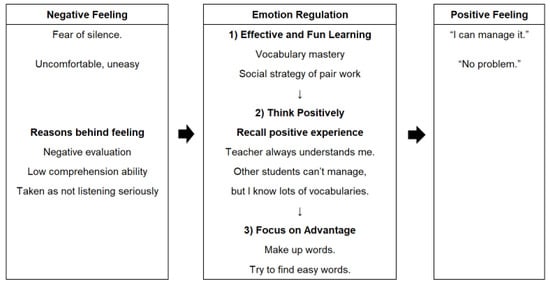

3.3. Emotion Regulation from Negative to Positive

The three features introduced above are all linked together to help transition a negative emotion into a positive one, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Transitioning emotions through regulation.

For example, when speaking with a native speaker, Taiga has an intense fear of silence, worrying he may be taken as having low comprehension ability or not listening seriously. Regarding language skills, he regulates his emotion to accomplish his everyday tasks of vocabulary learning by incorporating effective and fun elements. His high level of vocabulary mastery contributes to him recalling positive experiences he had in the past to allay his concerns: “I know lots of vocabulary, meaning I have high comprehension ability”, or “Teacher always understands me, so he may not think that I am not seriously listening”. This positive thinking leads him to focus on his advantages of having a rich vocabulary rather than being constrained by negative concerns towards speaking. This sequence of emotion regulation results in feeling positive and feeling, “I can manage it” at the very moment of speaking.

As shown above, it is observed that Taiga regulates anxiety by minimizing his worries by integrating multiple aspects of emotion regulation: language learning with efficient and fun elements, positive thinking recalling good past experience, and focusing on his advantageous language ability rather than negative concerns.

4. Discussion

The most important finding of the study is the changing nature of anxiety throughout the learning process. The learner’s anxiety manifested itself in different ways, at different times, and as a result of different triggers. The earliest indication of anxiety relates to Taiga’s literacy concerns, and this may have led him to associate the language classroom with anxiety [2]. This in turn may have led him to underestimate his language proficiency, something that learners with higher anxiety tend to do [30,31]. This presented itself as particularly important before and during his overseas visits. Furthermore, currently, Taiga experiences intense anxiety when speaking. The FLCAS responses indicate he starts to panic when he has to speak without preparation. His perception of a lack of control results in him manipulating performance conditions, especially through planning and practicing, as a result enables him to control the level of anxiety. This type of confidence-boosting regulation has been widely reported in the literature [3].

Another cause for anxiety with oral performance stems from the Japanese cultural norm of not wanting to stand out. Ohata [7] reports that Japanese learners, with a strong fear of sticking out from others, feel heightened anxiety to perform tasks in front of others, resulting in a negative impact on their L2 performance. Taiga hesitates to say something different from his classmates because they may make unpleasant comments about him or his language ability.

The method to regulate his anxiety also changes depending on the context; in the early days, speaking practice with native-speaker instructors helped him to overcome his literacy concerns and become more confident. The potential for a positive influence of communicating with native speakers has been reported before in the Japanese context [8].

Regarding the regulation of emotions, Taiga’s experiences show that these can not only overcome negative emotions but even provide motivation for hard work, such as careful preparation for class activities and frequent repetition. The existing literature indicates the negative effects of anxiety [17], almost to the exclusion of a possible positive influence. However, some evidence is now starting to emerge that has revealed that negative emotions can contribute meaningfully to success in learning. For example, Phung, Nakamura, and Reinders [32] found that an increase in anxiety in a speaking task was also accompanied by increased enjoyment, most likely, they argue, because the more challenging and anxiety-inducing tasks were also seen to be more interesting and motivating.

Taiga’s positive approach to dealing with his anxiety and his ability to create and then actively remember successful learning experiences may indicate his having or developing a growth mindset, which, Dweck and Yeager [22] describe as the belief that intelligence is not fixed but can be developed. If teachers can make learners believe that their language ability can be improved, then developing that ability can be important and obstacles can be identified during the learning process. Taiga shows this by using positive self-talk, for example “I can do it”, reflecting what has been recognized as a powerful contributor to dealing with anxiety [33].

5. Conclusions and Implications

Emotion is dynamic; it fluctuates and changes. The causes of negative emotions such as anxiety change over a long period of learning a language, and learners use different methods to regulate their emotions at each stage. In this study, during his thirteen years of learning, the learner’s anxiety was first caused by literacy concerns, but he was motivated to continue learning as a result of native speakers’ instruction and enjoyable materials. Later he attempted to overcome his communication concerns by preparing diligently before classroom activities and through intensive study.

Taiga currently has a high level of anxiety toward speaking with native speakers. He feels desperate or hopeless, even describing communication problems as being “The end.” The origin of this is his lack of confidence in unprepared speech, his fear of pauses that may reveal his limited language proficiency level, and his hesitation to ask the speaker to repeat the question as he fears this may upset him or her. However, he feels comfortable and confident by practicing with his peers before a presentation. To overcome his strong anxiety, Taiga uses multiple strategies to regulate his emotions, such as searching for effective ways to enjoy learning, thinking positively, and focusing on his strengths rather than weaknesses. He sets achievable goals for every task, from which he gains enjoyment, and this results in him having good experiences. Recalling these positive experiences drives positive emotions, and this helps him to overcome negative ones.

From a practical perspective, one of the implications of this study is for teachers to be aware of the importance emotions play in language learning. Regarding Taiga, his emotions colored most of his experiences as a learner. It is also worth identifying that negative emotions, such as anxiety, do not always discourage learning; with appropriate regulation or self-regulation they can be overcome or used as a motivating force. Therefore, an opportunity exists for language instructors to teach strategies for learners to reduce negative emotions and drive positive ones. Based on the growth mindset theory [22], it is suggested that instructors can help reduce learners’ negative feelings by leading them to believe that language can develop rather than staying fixed. If learners become aware of this, they may be able to see speaking as an opportunity for improvement, not just as a cause for anxiety.

Regarding Taiga, a beneficial element was the feedback and encouragement he received from his native speaker teachers. By setting achievable targets for classroom tasks that enable learners to see their progress, learners are more likely to develop confidence and find enjoyment in the process. For anxious learners such as Taiga, praising their efforts in having conversations or giving presentations is likely to be more helpful than pointing out errors.

From a theoretical perspective, tracing learners’ development longitudinally and dynamically can offer new insights [34]. For example, in our case, it revealed the changes in Taiga’s emotional experiences and how he dealt with them; something a static observation would have been unlikely to show. Another point is the importance of eliciting information about experiences in different contexts. Taiga showed different emotional responses in different situations, and studies of emotions, therefore, need to be sensitive to these. One way to accomplish this, as in our study, is to use multiple instruments, combining for example survey instruments to gain a broad overview of learners’ experiences, followed by in-depth interviews to investigate their background.

It is necessary to acknowledge the subjectivity of this study due to the nature of qualitative research. This explanation of the results shows only one interpretation, and the results cannot be generalized. Another concern is that the experiences during the learner’s early age were collected by his recollections, not having records of anxiety in-the-moment. The recollection of the emotion he experienced ten years later, may be different from the actual feeling he had in the learning environment at elementary school.

Further research is required to compare different learners’ emotional experiences longitudinally, to better understand the role of different situational variables. We believe that the richness of the emotional landscape, as revealed in this study, is extremely fertile ground for better understanding the language learning as experienced by learners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.N. and H.R.; data curation, N.S.N.; formal analysis, N.S.N. and H.R.; investigation, N.S.N. and H.R.; methodology, N.S.N. and H.R,; project administration, N.S.N.; supervision, H.R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.N.; writing—review and editing, N.S.N. and H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Chair of the Anaheim University ethics committee. Participation by the learner was voluntary and great care was taken to remind him of his right to withdraw at any time while creating a comfortable atmosphere during the data collection.

Informed Consent Statement

The respondent agreed to data use for research.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available if required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) | ||||||

| Results | ||||||

| March 20 and 5 July 2020 * 8 items took place in March (response marked in red) All 33 items took place in July (response marked in black) | ||||||

| * SD = strongly disagree; D = disagree; N = neither agree nor disagree; A = agree; SA = strongly agree. | ||||||

| (R) Reversed statements. | ||||||

| Bold: Items with anxiety positive response | ||||||

| Item # | Description | SD | D | N | A | SA |

| 1 | I never feel quite sure of myself when I am speaking in my foreign language class. | X | ||||

| 2 * | I don’t worry about making mistakes in language class (R). | X | X | |||

| 3 | I tremble when I know that I’m going to be called on in language class. | X | ||||

| 4 | It frightens me when I don’t understand what the teacher is saying in the foreign language. | X | ||||

| 5 | It wouldn’t bother me at all to take more foreign language classes (R). | X | ||||

| 6 | During language class, I find myself thinking about things that have nothing to do with the course. | X | ||||

| 7 | I keep thinking that the other students are better at languages than I am. | X | ||||

| 8 | I am usually at ease during tests in my language class (R). | X | ||||

| 9 * | I start to panic when I have to speak without preparation in language class. | XX | ||||

| 10 | I worry about the consequences of failing my foreign language class. | X | ||||

| 11 | I don’t understand why some people get so upset over foreign language classes (R). | X | ||||

| 12 | In language class, I can get so nervous I forget things I know. | X | ||||

| 13 * | It embarrasses me to volunteer answers in my language class. | XX | ||||

| 14 | I would not be nervous speaking the foreign language with native speakers (R). | X | ||||

| 15 | I get upset when I don’t understand what the teacher is correcting. | X | ||||

| 16* | Even if I am well prepared for language class, I feel anxious about it. | XX | ||||

| 17 | I often feel like not going to my language class. | X | ||||

| 18 * | I feel confident when I speak in foreign language class (R). | XX | ||||

| 19 | I am afraid that my language teacher is ready to correct every mistake I make. | X | ||||

| 20 * | I can feel my heart pounding when I’m going to be called on in language class. | XX | ||||

| 21 | The more I study for a language test, the more confused I get. | X | ||||

| 22 | I don’t feel pressure to prepare very well for language class (R). | X | ||||

| 23 * | I always feel that the other students speak the foreign language better than I do. | XX | ||||

| 24 | I feel very self-conscious about speaking the foreign language in front of other students. | X | ||||

| 25 | Language class moves so quickly I worry about getting left behind. | X | ||||

| 26 | I feel more tense and nervous in my language class than in my other classes. | X | ||||

| 27 * | I get nervous and confused when I am speaking in my language class. | XX | ||||

| 28 | When I’m on my way to language class, I feel very sure and relaxed (R). | X | ||||

| 29 | I get nervous when I don’t understand every word the language teacher says. | X | ||||

| 30 | I feel overwhelmed by the number of rules you have to learn to speak a foreign language. | X | ||||

| 31 | I am afraid that the other students will laugh at me when I speak the foreign language. | X | ||||

| 32 | I would probably feel comfortable around native speakers of the foreign language (R). | X | ||||

| 33 | I get nervous when the language teacher asks questions which I haven’t prepared in advance. | X | ||||

Appendix B

| Response on Strategy Inventory of Language Learning (SILL) | ||

| Results | ||

| 22 March 2020 | ||

| 1 = Never or almost never true of me | ||

| 2 = Usually not true of me | ||

| 3 = Somewhat true of me | ||

| 4 = Usually true of me | ||

| 5 = Always or almost always true of me | ||

| SL: Second language | ||

| Part A | Memory Strategies | Ratings |

| I remember new SL words or phrases by remembering their location on the page, on the board, or on a street sign. | 3 | |

| I use new SL words in a sentence so I can remember them. | 2 | |

| I remember a new SL word by making a mental picture of a situation in which the word might be used. | 2 | |

| I use rhymes to remember new SL words. | 2 | |

| I use flashcards to remember new SL words. | 2 | |

| I physically act out new SL words. | 2 | |

| I review SL lessons often. | 2 | |

| I connect the sound of a new SL word and an image or picture of the word to help me remember the word. | 1 | |

| I think of relationships between what I already know and new things I learn in the SL. | 1 | |

| Part B | Cognitive strategies | Ratings |

| I look for words in my own language that are similar to new words in the SL. | 3 | |

| I use the SL words I know in different ways. | 3 | |

| I try to find patterns in the SL. | 3 | |

| I find the meaning of an SL word by dividing it into parts that I understand. | 3 | |

| I say or write new SL words several times. | 3 | |

| I try to talk like native SL speakers. | 3 | |

| I practice the sounds of SL. | 3 | |

| I watch SL language TV shows spoken in SL or go to movies spoken in SL. | 3 | |

| I start conversations in the SL. | 2 | |

| I read for pleasure in the SL. | 2 | |

| I write notes, messages, letters, or reports in the SL. | 2 | |

| I first skim an SL passage (read over the passage quickly) then go back and read carefully. | 2 | |

| I try not to translate word for word. | 2 | |

| I make summaries of information that I hear or read in the SL. | 2 | |

| Part C | Compensation strategies | Ratings |

| I make up new words if I do not know the right ones in the SL. | 3 | |

| If I can’t think of an SL word, I use a word or phrase that means the same thing. | 3 | |

| To understand unfamiliar SL words, I make guesses. | 3 | |

| I read SL without looking up every new word. | 2 | |

| I try to guess what the other person will say next in the SL. | 2 | |

| When I can’t think of a word during a conversation in the SL, I use gestures. | 1 | |

| Part D | Metacognitive strategies | Ratings |

| I plan my schedule so I will have enough time to study SL. | 3 | |

| I have clear goals for improving my SL skills. | 3 | |

| I notice my SL mistakes and use that information to help me do better. | 3 | |

| I look for people I can talk to in SL. | 3 | |

| I pay attention when someone is speaking SL. | 3 | |

| I try to find out how to be a better learner of SL. | 3 | |

| I look for opportunities to read as much as possible in SL. | 3 | |

| I think about my progress in learning SL. | 2 | |

| I try to find as many ways as I can to use my SL. | 1 | |

| Part E | Affective strategies | Ratings |

| I give myself a reward or treat when I do well in SL. | 2 | |

| I write down my feelings in a language learning dairy. | 2 | |

| I encourage myself to speak SL even when I am afraid of making a mistake. | 2 | |

| I notice if I am tense or nervous when I am studying or using SL. | 2 | |

| I talk to someone else about how I feel when I am learning SL. | 2 | |

| I try to relax whenever I feel afraid of using SL. | 2 | |

| Part F | Social strategies | Ratings |

| If I do not understand something in SL, I ask the other person to slow down or say it again. | 3 | |

| I ask SL speakers to correct me when I talk. | 2 | |

| I practice SL with other students. | 2 | |

| I ask for help from SL speakers. | 2 | |

| I ask questions in SL. | 2 | |

| I try to learn about the culture of SL speakers. | 2 | |

Appendix C. Interview Flow and Questions

1st Interview (took place on 23 March 2020)

I. Introduction

Thank you for participating in this interview. The learning from this interview is very important for my research, but would you please feel relaxed as there is no right or wrong answers. I would like you to feel free to talk what comes up to your mind on the questions I give you.

As I will not be able to take notes, may I record this conversation? Thank you.

II. Anxiety

Let me know more about what you answered in the questionnaire. You mention that you feel some kind of anxiety in learning English.

- (1)

- Intensity

Will you tell me how strong it is? Is it “extremely” strong or “a little bit” strong?

- (2)

- Frequency/Nature of anxiety

Do you feel that way all the time learning English OR is it different by occasion, such as when speaking as you mention in the questionnaire?

In which occasion do you feel “extremely strong” in learning English?

Will you tell me about your experience?

What are other experiences that you feel strong anxiety about?

Do you feel the same way in Japanese classes? If not, why is that?

- Speaking in front of the class.

- Other students do better. In what occasion?

- Taking tests.

III. Learning strategies/How does he overcome anxiety?

Next, let me know what you do to overcome such anxiety. What do you do to make yourself feel motivated to learn English?

1. Overall

- (1)

- Will you tell me what you actually do?

- (2)

- Tell me what makes you feel that you are doing ok or feel more comfortable?

- (3)

- What experience made you start doing so?

- (4)

- Are there anything that you tried but found that it doesn’t work well?

2. SILL results

(1) Among the strategies listed in the questionnaire, you mention that you use the following 5 practices, which ones do you think to be very effective for your learning, and why do you think so?

- Review English lesson often. → What do you actually do? Why do you do so?

- I say or write new English words several times.

- Try to talk like native speakers.

- I watch English language TV shows spoken in English or go to movies spoken in English.

- If I can’t think of an English word, I use a word or phrase that means the same thing.

(2) You don’t use many of the memory-related practices listed in the questionnaire. Will you tell me why?

2nd Interview (took place on 12 July 2020)

I. Introduction

Thank you for participating in this second interview. The learning from this second interview is also very important for my research, but would you please feel relaxed as there is no right or wrong answers. I would like you to feel free to talk what comes up to your mind on the questions I give you.

As I will not be able to take notes, may I record this conversation? Thank you.

II. Experiences in language learning.

Let me know about the language learning experiences.

- (1)

- When is the first experience learning, do you remember?

- (2)

- What do you remember about it? (Textbook, teachers, etc.)

- (3)

- How did you like it? Did you enjoy it, or not?

If you enjoyed it, what made you feel so. If not, why not?

- (4)

- Especially on the occasion he felt anxiety:

What exactly happened to you?

What made you feel so?

Did you do something to overcome such feelings?

- Elementary school English lesson by the native speaker instructor, Mr. Moritch.

- Home stay at Michael’s house in Australia.

References

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Gregersen, T. Affect: The role of language anxiety and other emotions in language learn-ing. In Psychology for Language Learning; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, P.D. 2. MacIntyre, P.D. 2. An Overview of Language Anxiety Research and Trends in its Development. In New Insights into Language Anxiety; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2017; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez López, M.G.; Bautista Tun, M. Motivating and demotivating factors for students with low emotional intelligence to participate in speaking activities. Profile Issues Teach. Prof. Dev. 2017, 19, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Garza, T.J.; Horwitz, E.K. Foreign Language Reading Anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 1999, 83, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodrow, L. Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language. RELC J. 2006, 37, 308–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Said, M.M.; Weda, S. English Language Anxiety and Its Impacts on Students’ Oral Communication among Indonesian Students: A Case Study at Tadulako University and Universitas Negeri Makassar. TESOL Int.-Natl. J. 2018, 13, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ohata, K. Potential sources of anxiety for Japanese learners of English: Preliminary case interviews with five Japanese college students in the US. TESL-EJ 2005, 9, n3. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, D.J.; Ross, A.S. Communicative interactions in foreign language education: Contact anxiety, appraisal and distance. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2018, 16, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Yashima, T.; Humphries, S.; Aubrey, S.; Ikeda, M. 4. Silence and Anxiety in the English-Medium Classroom of Japanese Universities: A Longitudinal Intervention Study. East Asian Perspect. Silenc. Engl. Lang. Educ. 2020, 6, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, S.; Yang, Y.L. The English language classroom anxiety scale: Test construction, reliability, and validity. JALT J. 2003, 25, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Imada, H. Cross-language comparisons of emotional terms with special reference to the concept of anxiety. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 1989, 31, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S. The distinctive characteristics of foreign language teachers. Lang. Teach. Res. 2006, 10, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, T.; Macintyre, P.D.; Meza, M.D. The motion of emotion: Idiodynamic case studies of learners’ foreign language anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 2014, 98, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, M. Why Do People Regulate Their Emotions? A Taxonomy of Motives in Emotion Regulation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 20, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.; Oxford, R.L. The twenty-first century landscape of language learning strategies: Introduction to this special issue. Syst. 2014, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, R.L. Teaching and Researching Language Learning Strategies: Self-Regulation in Context; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford, R.L. Language Learning Styles and Strategies: An Overview. In Proceedings of the GALA (Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition) Conference; 2003; pp. 1–25. Available online: http://web.ntpu.edu.tw/~language/workshop/read2.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Bown, J.; White, C. Affect in a self-regulatory framework for language learning. System 2010, 38, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H.; Harbon, L. Self-Regulation in Second Language Learning: An Investigation of theKanji-Learning Task. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2013, 46, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benita, M.; Kehat, R.; Zaba, R.; Blumenkranz, Y.; Kessler, G.; Bar-Sella, A.; Tamir, M. Choosing to Regulate Emotions: Pursuing Emotion Goals in Autonomy-Supportive and Controlling Contexts. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 45, 1666–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Yeager, D.S. Mindsets: A View From Two Eras. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, T. Dynamic properties of language anxiety. Stud. Second. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2020, 10, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horwitz, E.K.; Horwitz, M.B.; Cope, J. Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 1986, 70, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.-M.; MacIntyre, P.D. The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Stud. Second. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2014, 4, 237–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oxford, R.L. Language Learning Strategies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- McRae, K.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation. Emotion 2020, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, D.; Bailey, K.M. Exploring Second Language Classroom Research: A Comprehensive Guide; Cengage Learning: Melbourne, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbinghaus, H. Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology. Ann. Neurosci. 2013, 20, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Noels, K.A.; Clément, R. Biases in Self-Ratings of Second Language Proficiency: The Role of Language Anxiety. Lang. Learn. 1997, 47, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.J. Questioning the Stability of Learner Anxiety in the Ability-Grouped Foreign Language Class-room. Asian EFL J. Q. 2014, 16, 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Phung, L.; Nakamura, S.; Reinders, H. Learner engagement and subjective responses to tasks in an efl context. Focus 2019, 4, 456. [Google Scholar]

- Young, D.J. Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does language anxiety research suggest? Mod. Lang. J. 1991, 75, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Kawaguchi, S. Acquisition of English morphology by a Japanese school-aged child: A longitudinal study. Asian EFL J. Q. 2014, 16, 89–119. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).