1. Introduction

1.1. Communication Skills and Communicative Competence

New graduates are supposed to possess a broad set of cognitive, affective, personal, social, and communication skills that should help them achieve their full potential in varied social contexts, as well as adjust to rapidly changing environments and labor market demands. This broad set of skills, referred to as “21st century skills”, is valued in educational and professional environments and, therefore, becomes pivotal for academic and career success of individuals. The need to develop a sound theoretical framework, embracing the diversity of 21st century skills, resulted in a growing number of studies, suggesting varied sets of skills from different theoretical perspectives. It is stated that these skills should be developed in the context of teaching core subject areas and should equip students with the competencies necessary for their personal and professional well-being. It becomes evident that students cannot acquire these skills when exposed to traditional, for academic institutions, methods of instruction. On that account, teaching students the skills for the future poses a challenge for educators, raising several questions: Which skills should be considered as critical in educational context? Which instructional methods could be used to foster the development of necessary skills? What sort of content should be delivered to students?

The majority of studies propose that communication skills are the backbone of skills for the future, as they are “a gateway to developing other soft skills” [

1] (p. 11). Communication, in broad terms, is the process (or act) of sharing concepts and ideas, exchanging feelings and emotions through different means in order to develop meaning and create shared understanding among specific groups in varied contexts. Having a complex nature, communication has been studied from varied perspectives, which resulted in creating a wide range of communication models [

2]. From the language teaching perspective, it is commonly thought that communication comprises several basic domains, such as reading, writing, listening, and speaking. However, communication is a more complex phenomenon. Communication might occur in varied social and cultural contexts and might serve different goals. It means that, in order to communicate effectively, a person needs to interpret social contexts and cultural clues to understand the intentions of other participants, to decode the messages, and derive appropriate meaning. Communication also stipulates the ability to express ideas clearly and in a coherent manner, motivate others through speech, deliver instructions, negotiate, persuade etc. [

3]. Hence, communication skills go far beyond the purely linguistic proficiency to include pragmatic, strategic, discursive, and cultural aspects. In this regard, effective communication might be interpreted as communication that helps achieve desired outcomes [

4]. For this reason, strong communication skills are highly valued in a professional environment [

5]; they have a significant impact on students’ academic success [

6].

In terms of foreign language (FL) teaching, instructional strategies and learning approaches are primarily focused on the development of communicative competence, since the ability to converse with others, to accurately use the linguistic systems in an effective manner, is recognized as the strategic goal of foreign language training. The concept of communicative competence has been disclosed in the literature from different theoretical perspectives, primarily behavioral, cognitive, and social [

7,

8,

9].

Varied theoretical views on the essence of communicative competence in practice have led to generating different frameworks of its components. For instance, Canale, Swain, Savignon proposed a model of communicative competence which comprised three core components: grammatical competence—referred to as the knowledge of morphological, syntactic, semantic, phonetic, orthographic rules, and “lexical items”; sociolinguistic competence—perceived as the knowledge required for effective interaction in different cultures, contexts, and situations; strategic competence—the knowledge of how to use language resources in order to communicate intended meaning [

10]. In later works of Canale, “discourse competence” as the knowledge of varied connections among utterances in the text, necessary to generate a meaningful whole, was proposed as the fourth component of communicative competence. In the framework of language testing, Bachman and Palmer took a broader perspective on language proficiency and communicative competence, suggesting to consider the communicative language ability as well as to recognize the importance of context beyond the sentence and its impact on the appropriate language usage. Thus, it subsumes two core components: strategic competence (metacognitive strategies) and language knowledge. Strategic competence addresses a set of metacognitive components which ensure cognitive management function in language use, for instance, goal setting, assessment, and planning. Language knowledge embodies organizational knowledge (grammatical and textual knowledge) and pragmatic knowledge (functional knowledge and sociolinguistic knowledge) [

11]. In this model, strategic competence constitutes a core component of communicative competence alongside language competence, as it might include the strategies that are not purely linguistic. In recent works of Celce-Murcia et al. and Littlewood, communicative competence has been considered as a construct comprising linguistic, discourse, actional, sociocultural and strategic competences [

12]; or linguistic discourse, pragmatic, sociolinguistic, and sociocultural competences [

13]. Multiple theories of communicative competence recognize the importance of strategic competence. In some, it appears to be at the core of communicative competence, tying up all other components in one balanced whole. However, most of the frameworks tend to focus on an individual producing the language rather than on individuals who interact to reach mutual understanding. Meanwhile, namely the strategic competence, as a set of skills to plan, assess, evaluate, monitor, select the language patterns appropriate to the context, to achieve intended goals, to produce accurate utterances, and is at the forefront of improving the communicative competence and interactional abilities of a learner.

1.2. Strategic Competence and Communication Strategies

In the university practice of foreign language teaching and learning, a great deal of attention is given to the development of linguistic knowledge and accuracy, and considerably less attention is paid to fostering strategic competence [

14]. There might be various reasons for this. Firstly, there are several approaches to define the concept of strategic competence. For instance, it is defined as: (a) verbal and non-verbal communication strategies that are used to compensate for breakdowns in interaction, especially when there is a deficit in one of the other competencies [

15]; (b) as metacognitive strategies, namely cognitive management, function in language use, that help to relate language knowledge (competence) to the context the language is used in and to the discourse, deriving from interaction [

11]; (c) as a combination of metacognitive strategies that ensures the mental processes of planning, assessing, monitoring, testing, and evaluating in communication and cognitive strategies that enable the processing of information at different stages and solve problems encountered in the process of communication and actual language use [

16]; (d) as a construct that comprises sociolinguistic competence aimed at adapting oral interaction, and the ability to tie this competence to the knowledge of the context and discourse while communicating [

17]. Secondly, it was prior assumed that the strategic competence could be transferred from L1 to L2 [

18]. Given that teaching the foreign language did not imply any specific attention to the development of strategic competence in a foreign language classroom.

Thirdly, acknowledging the fact that real time communication in foreign language is cognitively demanding, as participants are exposed to coding and decoding messages, conveying and interpreting the meaning, accomplishing personal communicative goals, and adjusting to social contexts and communicative goals of other participants, the interaction process involves not only the sole usage of linguistic resources but also specific strategies that could ensure the effectiveness of communication in varied settings. In the field of applied linguistics, strategic competence has been associated with the use of oral communication strategies, however, to date there is no agreement on their taxonomy.

Several approaches have been taken to the identification and classification of communication strategies, namely “psycholinguistic” and “interactional.” From the psychological problem-solving perspective, speakers, when they lack the linguistic resources, address communication strategies to resolve their communicative problems. Besides that, the psycholinguistic approach tends to explain the usage of communication strategies with regard to the model depicting the inner processes of speech production. This perspective limits the research to the problem-solution approach which cannot clearly articulate the nature of reciprocal engagement in communication aimed at developing mutual understanding. Moreover, the significance of metacognition, which is involved in the process of regulating the communication flow, remains unaddressed. In line with the interactional perspective, the attention is mainly directed to the interactional essence of communication, and therefore, the strategic competence is defined as an attempt to generate mutual understanding and meaning among several interlocutors. In broad terms, it is possible to define two major types of communication strategies: message adjustment strategies, also referred to as reduction and avoidance strategies, and resource expansion strategies, also termed as achievement strategies [

14]. There is a number of taxonomies that support the current research on strategic competence. Thus, one of Tarone’s pioneering works contained the following classification of communication strategies: (1) avoidance (topic avoidance or message abandonment); (2) paraphrase (approximation, word coinage, circumlocution); (3) borrowing (literal translation, language mix); (4) appeal for assistance; (5) mime [

10]. Although Tarone advocated an interactional approach to the research of communication strategies, the author’s taxonomy was primarily focused on the problem resolving procedures employed by a speaker–foreign language learner. Other taxonomies, developed by Poulisse and Dornyei, embodied compensatory strategies, conceptual strategies, and linguistic strategies, as well as interactional strategies, such as checking for understanding or asking for clarification, and indirect strategies which are employed to maintain the conversation flow or gain time using fillers and hesitation [

14]. The authors mostly focused on practical solutions of how to introduce the training of strategic competence (communication strategies) in a foreign language classroom. Another taxonomy, which strongly emphasized the interactional perspective on communication, was introduced by Nakatani [

19]. The author suggested a set of the oral communication strategies for coping with listening (negotiation for meaning while listening strategies, fluency-maintaining strategies, scanning strategies, getting the gist strategies, nonverbal strategies while listening, less active listener strategies, word-oriented strategies) and speech production problems (social affective strategies, fluency-oriented strategies, negotiation for meaning while speaking strategies, accuracy-oriented strategies, message reduction and alteration strategies, nonverbal strategies while speaking, message abandonment strategies, attempt to think in English strategies) [

19].

The fourth point to be mentioned is referred to the “teachability of communication strategies” (Dörnyei). Some studies reveal that communication strategies could be and should be taught in a foreign language classroom, besides that, the explicit instruction (direct approach) is considered to be the most preferable and effective [

20]. However, there is still no agreement on the rationale for introducing strategy-oriented training in a foreign language classroom as a few studies have evaluated its effectiveness from a pedagogical perspective as well as few studies have investigated the effectiveness of strategic language training in the context of students’ future professions [

21]. It should also be stated that not all communication strategies, commonly used by foreign language learners, should be taught in the classroom. For instance, strategies such as word coinage, code switching, foreignizing, or borrowing might not appear beneficial in the process of communication, especially in a professional setting. Meanwhile, some strategies such as approximation, paraphrase, use of fillers/hesitation devices, checking for understanding, asking for clarification, or non-verbal strategies might contribute to effective communication.

In this study, strategic competence is defined as a set of specific skills that allows an individual to use verbal and non-verbal communication strategies that are appropriate to a certain social context.

Communication strategies are of particular importance in a professional environment, especially for those whose profession is tightly connected with effective communication. We believe that some communication strategies are “universal” and are used in L1 and L2 by speakers, specifically those that are employed at metacognitive level. Such strategies are involved in the processes of planning communication, assessing actual communication, evaluating the appropriateness of the language produced, improvising in the course of communication. Yet, there are some strategies that are important for foreign language users that reflect and reconstruct the strategic and interactional essence of communication. In this study, we focus on pre-service language teachers (teacher-students) and the communication strategies and skills they need to achieve desired outcomes in a foreign language classroom.

Communication is at the heart of the teaching profession. Moreover, studies have shown that effective teachers’ performance in the classroom and students’ academic achievement significantly depend on communication skills of a teacher [

22]. Classroom communication is a complex phenomenon which is rather different from other types of communication between people. Firstly, it is quite regulated, as educators and students are supposed to follow certain behavioral patterns conditioned by their social statuses and specific social and educational contexts [

23]. Secondly, being multiple goals-oriented, communication in the classroom aims at instructing, informing, explaining, responding to the needs of a learner, eliciting, modelling, giving feedback, managing the learners, encouraging, and assessing. Thirdly, communication in the classroom might be quite unpredictable as well as plan driven. This demands from a teacher that they demonstrate both good improvisational and planning skills while interacting with learners.

The analysis of observation reports of pre-service FL teachers’ activity in the classroom, as a matter of their teaching practice, for several months allowed us to determine a set of core communication strategies that novice teachers had struggled to use in the classroom discourse and, therefore, should be trained on in order to be more resultative and confident in communication with learners. We assume that the core difficulties in the course of their teaching practice are attributed to the following reasons: (1) little exposure to “true-to-life” situations that occur in a professional setting: (2) the lack of necessary skills for planning classroom communication as a communicative event, as well as for assessing the effectiveness of communication and reflecting on positive and negative practices; (3) poor professional communication skills that are required to support the educational goals of a teacher; (4) little exposure to the authentic classroom language that is used by native FL teachers. Being language learners themselves, non-native novice FL teachers appeared to be challenged organizing interactive oral communication in the classroom. To this end, training novice teachers in paraphrasing, questioning, maintaining the conversation flow, maintaining fluency, and accuracy becomes of primary importance.

The necessity to develop professionally bound communication skills raises a question on methods, techniques, and assessment procedures that could be productive in FL communication training at a university level. In this regard, we hypothesized that students could be effectively trained to use professional communication strategies if they were exposed to real or close-to-real scenarios that might occur in their professional sphere.

1.3. Scenario-Based Communication Training in Higher Education

Teacher training programs employ multiple approaches, such as lectures, role-plays, and seminars, to prepare pre-service teachers for varied and challenging classroom contexts [

24]. However, the traditional “transmission of knowledge” model is still predominating in the practice of Higher education [

25]. To this end, students report “a lack of connection between what is learned in university and what they come to encounter in ‘real life’ situations” [

25] (p. 193). As a result, students feel unprepared for their future roles as they have not had enough exposure to the context of their future professions. It calls for the necessity to introduce students to active learning strategies, which allow them to take a more active role in their studies. Scenario-based learning is reported to be an important component of multiple active learning approaches [

25].

The term “scenario” has numerous definitions and is used in varied contexts, for instance, in performing arts, literature, strategic planning, etc. Scenarios are also used as tools to define the plausibility of some future situations linked to certain circumstances as well as to provide a number of likely outcomes regarding specific issues [

26].

In teaching practice, scenario-based learning (SBL) is defined as any educational approach that stipulates the usage of scenario in order to “bring about desired learning intentions” [

27] (p. 2). Scenarios may include multiple things, for instance, a set of circumstances, a description of people’s behavior, a story or an outline of events, an incident in the professional setting, a dilemma, but each should carry a learning experience. In scenario-based learning, students are exposed to a scenario that might contain several questions to guide their inquiry. Students explore a scenario from different perspectives, being placed in a position where they should demonstrate varied skills or procedures, speculate on professional knowledge, or tackle a problem or an issue. Scenarios create a safe learning environment. Even in the situation of a wrong choice/move/decision, students do not experience the consequences that might occur in a real professional setting. Scenarios are quite often scaffolded by guided observation, discussion, paired deliberations, debate, role-plays, teamwork, and periods of reflection [

28]. The choice of scaffolding correlates with the specific aspects of professional settings. Thus, for pre-service teachers, a classroom setting is the most engaging way to experience the issues that might occur in daily professional routines. Overall, SBL helps students to bridge the gap between the theory and the reality of professional practice as it provides authentic or realistic contexts for learning, to experience real life situations of future profession via simulating activities, to analyze gained experiences, to make decisions and evaluate their appropriateness, and to practice professional collaboration [

27].

There are several types of scenarios that could be used by university educators: skills-based scenarios, problem-based scenarios, issue-based scenarios, or speculative-based scenarios. Each scenario aims at fostering specific aspects of students’ quasi professional activity. Thus, skills-based scenarios allow students to practice acquired skills or demonstrate theoretical knowledge, especially underlying some fixed procedures or instructions. With problem-based scenarios, students identify their existing knowledge and the areas to be explored, construct and apply the knowledge while facing varied challenges, learn to react to arising problems, and reflect on solutions and possible outcomes. Issue-based scenarios are used to promote students’ understanding of contextual issues common for the profession and provide the opportunity to compare and contrast different perspectives. Speculative scenarios are employed to encourage students to research facts, trends, and any sort of data within their professional sphere in order to speculate on future or analyze the past experiences [

27]. Along with these types, researchers also distinguish between narrative scenarios—a story-based scenario which presents a person, willing or motivated to use a system of actions in a certain situation in order to achieve a goal, and gaming scenarios—the ones, based on a game, to add fun and emotional involvement to learning processes [

26]. To create an engaging experience for learners, it is necessary to consider several characteristics of SBL: challenge, narrative, choice, roles, role-play, authenticity, setting of the scenario, characters in the scenario, and scenario learning objectives [

29]. Once properly created, scenarios in learning process stimulate the acquisition of strategies required for professions and enable learners to build the skills needed for managing their learning difficulties [

30].

In language training, scenario-based instruction is an interactive approach that challenges the learners to choose between the communication strategies that are similar to real world discourse. The interactive approach to learning and training appears to be effective, as it involves the learner in the learning process at cognitive, emotional, and behavioral levels [

31]. Professional communication training implies strategic interaction as a matter of specific communication strategies used to ensure the achievement of desired outcomes [

32]. These strategies are employed to convey the message, to build on mutual understanding and meaning, to perform a certain role while communicating. Strategic professional language training, with the use of scenarios, enables learners to immerse in “real world” situations where they are able to learn and improve required skills, construct their knowledge, perform professional roles, and reflect on positive and negative practices in safe learning environment.

1.4. Aim of the Study

Since it has been hypothesized that, in the context of Higher education, scenarios can be employed to improve FL communication skills, the present study seeks to answer the following research questions:

What communication strategies and skills are principal for novice FL teachers?

Can SB instruction enhance the development of professional communication skills and strategic competence?

How can scenario-based instruction be implemented in communication training What is the pedagogical implication of SB instruction in foreign language training at a university level?

4. Discussion

The present research primarily focused on identifying the way to improve professional communication skills and strategic competence during FL training in the context of Higher education. Communication plays a pivotal socializing role, allowing students to learn the norms of speech, patterns, and rules of communicative behavior that are common for varied social contexts [

37]. The study recognized the necessity to deliver strategic foreign language training in the context of professional communication. In this research, the attention was directed to the training of pre-service FL teachers. Thus, one of the focal points was to define the communication strategies that could enable novice FL teachers to organize productive communication in the classroom. It was further assumed that professional communication training would be effective if arranged in tight relation with “real world situations” (scenarios) that would occur in a professional setting. This assumption led to the necessity to develop the teaching procedure to enhance the effectiveness of scenario-based instruction in foreign language training.

In the field of linguistics and foreign language education, communication strategies are extensively researched from varied perspectives. A great number of recent studies focus on the classroom discourse as a matter of teacher-student interaction analysis, namely, the language used to convey the message, the discourse patterns, the ways of transmission and reception of information, the roles of the participants, communication style, etc. [

38]. This line of research generally addresses the issues of “teacher talk” in the class-room, specifically the balance between the teacher-student talking time, the use of imperatives and questions, and the linguistic and sociolinguistic aspects of FL teachers’ speech [

23]. Another strand of research is mostly attributed to the analysis of communication strategies used in FL classroom by language learners [

10,

14,

19,

20]. In this regard, communication strategies are mostly considered as compensation strategies that help to avoid communication breakdowns. However, few studies have focused on communication strategies used by FL teachers in the classroom as well as the ways pre-service teachers can be trained to become effective communicators.

We believe that communication strategies used by (non-native) FL teachers in the classroom are complex in their nature. Firstly, these strategies are aimed at delivering and managing the pedagogical content of the lesson, so the strategic nature of communication (teacher talk) is contextually and professionally bound. Secondly, communication strategies in FL classroom are used by teachers to represent the foreign language models, to model communication patterns, and to support the classroom interaction. Thirdly, the effective use of communication strategies indeed helps to avoid any breakdowns in classroom communication.

In recent studies on classroom, discourse communication strategies, such as questioning or keeping the conversation flow, are recognized as a core for productive classroom communication [

23,

38].

It is also worth mentioning that, due to the lack of clarity concerning the distinction between such terms as strategy, technique, sub-strategy, tactic, and move. In this study, we referred to the word strategy, yet acknowledging the importance of differentiating one from another, especially in the context of linguistic studies [

39].

Our study suggests that questioning and maintaining the conversation flow together with the paraphrasing strategy should be considered as the most critical strategies for pre-service FL teachers. Importantly, these strategies appeared to be quite difficult for students to master.

Questioning is one of the most important communication strategies for FL teachers [

40]. In the context of classroom discourse, it is common to differentiate between display and referential questions. Referential questions provoke learners’ thinking, and a teacher might only guess what sort of answers s/he could receive. Display questions are those that aim at eliciting specific knowledge from students and a teacher knows what kind of answer s/he expects from students. Thus, concerning the first group of questions the main difficulty for students was to arrange a sequence of questions that could logically lead to the next activity or be used as a matter of learners speaking practice. In this regard, it was assumed that planning, as a metacognitive strategy underlay, the ability of students to arrange meaningful communication and, therefore should be addressed at the instructional level. The second group of questions (display questions) refer to the communication strategy of asking for clarification or checking the understanding. In the practice of FL teaching, display questions are used to check the concept and instruction understating (CCQs and ICQs). Concept checking questions (CCQs) and instruction checking questions (ICQs) are targeted questions commonly used by a FL teacher in the classroom. CCQs help a teacher to gain an accurate evaluation of students’ comprehension of the things being taught, and ICQs are used by teachers to check whether the students understand the instruction given before the task completion. It was observed that students were not able to use these questions, as they were challenged to understand what sort of concepts had to be checked during the lesson, and how to weave these questions into the communication flow.

In FL classrooms, teachers need to adapt to the level of students’ language proficiency, so they need to vary their language in terms of grammar and vocabulary to make a clear and meaningful statement. In this regard, paraphrasing is another strategy that constitutes the core of FL classroom interaction. It was noticed that intern-teachers tended to use the grammar structures which were not entirely correct in order to make them comprehensible for learners. It was also hard for students to explain the meaning of some words, in particular, to adapt their language to the proficiency level of their potential students. Moreover, they could not see the opportunities for attracting non-verbal or visual resources, such as miming, gesturing or relevant realia. Instead, they would use complicated “dictionary-like” definitions of unclear words to build on linguistic comprehension of their learners. Meanwhile, non-verbal strategies can contribute to effective classroom interaction [

41]. Non-verbal strategies, such as miming or gesturing, help a teacher to convey the necessary meaning, in particular, explain concepts, correct learners’ mistakes or give instructions. They also help to create a more relaxed and dynamic atmosphere in the classroom. Novice teachers quite often fail to use non-verbal strategies as they cannot immediately assess the situation and instantly come up with the gestures that could be demonstrative and time-effective.

Another set of challenges was attributed to novice teachers’ skills to maintain the conversation flow in the classroom. Firstly, it appeared that pre-service teachers could not provide the learners with an immediate response while interacting with them. Instead, they would nod or just turn to another student to proceed with the activity. Secondly, they also were challenged to use some encouraging (or praising) techniques that could stimulate the learner and help build on learners’ confidence. In situations when students were distracted, or did not want to finish the activity, it was hard for teachers to attract the learners’ attention.

It is also worth mentioning that, while assessing students’ performance, we also noticed that teacher-students used the avoidance strategy in situations when: (a) they were confused to explain the meaning of the word to learners; (b) some grammar structure or lexical units, which were above the level of learners’ proficiency, appeared in the flow of communication; (c) when the initial lesson plan did not stipulate the discussion of the topic raised by learners, therefore it was hard for novice teachers to deviate from their lesson plans and initiate the “natural” discussion.

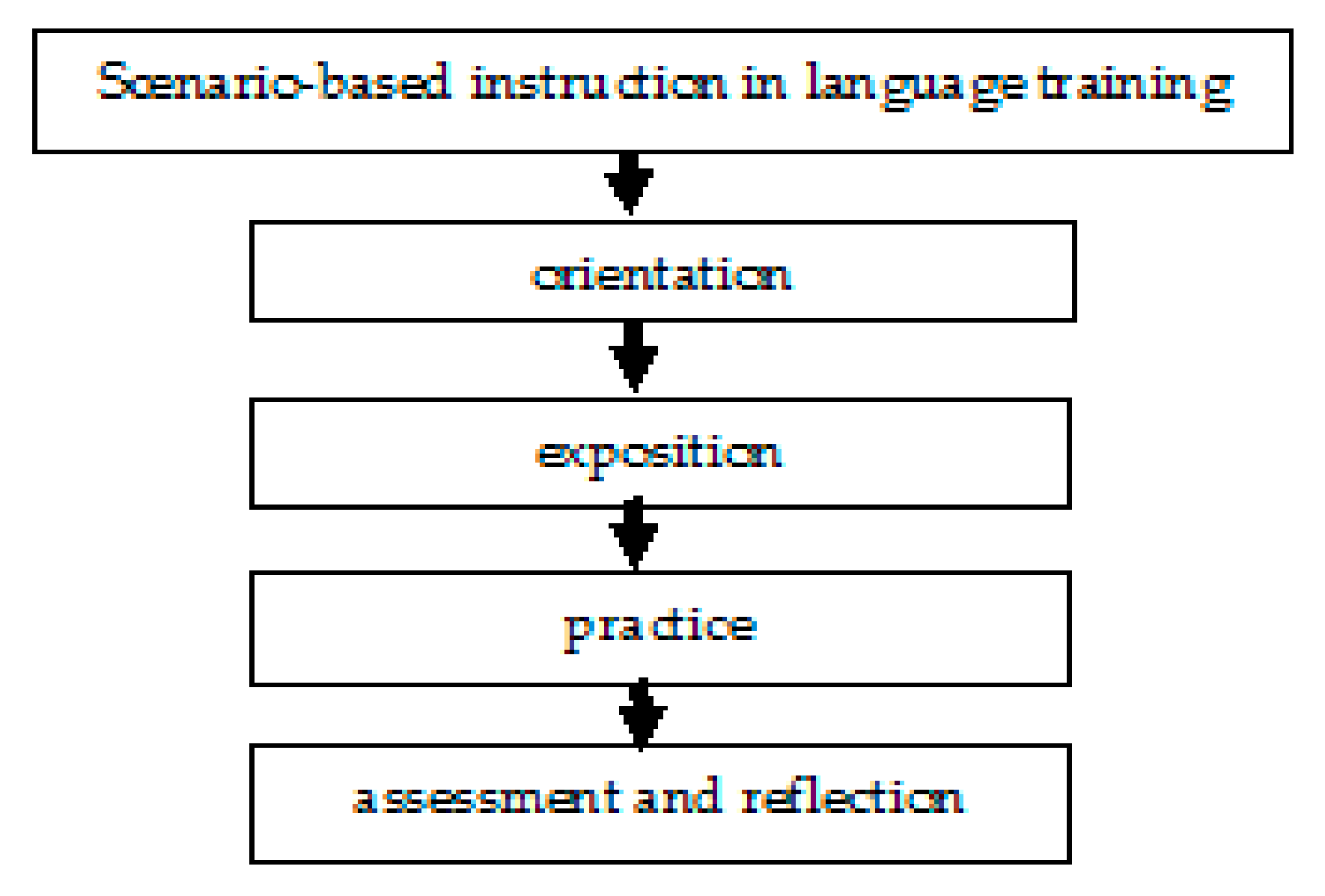

The analysis of students’ pitfalls allowed us to model the 4-step scenario-based instructional procedure that could enable the students to master the strategies in “close to real life” professional settings. It was hypothesized that successful scenario-based classroom instruction had to comprise several stages such as exposition, orientation, practice. Our assumption echoed the idea prior suggested by Sukirlan [

42]. However, in the course of our research, we came to the conclusion that to make the communication training more effective, the assessment and reflection stage had to be emphasized. They had to include formative assessment, summative assessment, self-assessment, peer-assessment, and self-reflection, as these procedures promote the development of relevant professional skills as well as cognitive and metacognitive strategies [

43] (see

Figure 1).

At each instructional stage, varied scenarios were employed to support the learning process. Overall, a scenario contained the description of a typical classroom discourse situation.

At the orientation stage, we used scenarios that helped to build linguistic awareness of students. These scenarios contained an extract from classroom discourse that reflected the real situations of classroom interaction. The students were supposed to fill in the gaps, choosing between appropriate phrases, or suggest their own wording that would fit the context of the given situation. At this stage we also introduced the students to the specific strategy that would be further trained.

At the stage of exposition, the students observed the models of behavior demonstrated by other practitioners. To this end, we used different open resources to find short videos that depicted necessary strategies. It was important that these videos contained a challenge that would make it hard to predict the outcomes of communication and were authentic in terms of language. The students worked in small groups, to analyze the behavior of a teacher and students, to anticipate the problems that might occur in classroom communication.

At the practice stage, the students were introduced to scenarios that were further analyzed and acted out. At this stage we used role-plays and open class discussions to reflect on good practices and develop a step-by-step procedure of implementing strategies in real settings [

44].

At the assessment and reflection stage, the students were supposed to demonstrate the skills acquired. The educator assessed the students’ performance while they were delivering the lesson parts based on the scenario they had received. The results were discussed with the student and the group. The students were supposed to share observations and discuss the strong and weak points of the performance. Collaborative work at every stage helps students to build confidence, acquire necessary team-working skills, and develop a professional identity [

45]. Overall, the sequential implementation of each step of scenario-based instruction involves students into productive theory analysis, reflective analysis of behavioral models, theorizing, practice and reflective self and peer assessment. It helps students to build on personal knowledge and practices that could enhance the teaching repertoire [

46].

The research has shown that scenario-based instruction can significantly enhance the communication skills of learners. Being an interactive method of teaching, it provides the learners with the opportunities to try out varied communicative situations where they need to discuss, assert their opinions, role play, and act out the scenarios. It also allows arranging strategic communication training which, if necessary, could be limited to the behavioral and communication patterns that need specific attention. Scenario-based instruction helps students to acquire and improve professional communication skills in a safe learning environment, where they learn to analyze their difficulties and develop the strategies for effective learning and communication.

The core pedagogical implication of SB instruction is that it significantly changes the roles of an educator and students. The students become the active participants in their learning. They observe, analyze, gather information, explore, and practice which might also foster their cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies. The role of an educator is to guide the students and render support at times when students need to detect the areas of their improvement. The core objectives of an educator while conducting training sessions could be formulated as follows:

to create conditions for students that enable them to acquire and improve their skills and competencies;

to provide the feedback and support, so the students could detect the area of their further improvement and envisage its path;

to develop the learners’ skills and competencies by enabling the learner to take an active role;

to foster students’ motivation through challenging activities and collaborative work;

to attract varied resources in order to make the learning process more engaging.

Scenario-based instruction may also support students in adapting to their professional roles. It equips the educator with the opportunities to create the learning environment, which helps learners to manage anxiety and build confidence. Helping students to adapt to their social and professional roles is as important as providing them with diverse learning opportunities, since adaptation stipulates the development of skills needed for independent professional work and personal fulfillment [

47].

As a matter of practical implications, the research contributes to the practical knowledge of developing the instructional strategy while delivering the scenario-based training to students. The developed 4-step instructional procedure might be used to teach other subjects at university. If so, the main focus should be directed to defining the core objectives of the course or a discipline, selecting relative scenarios (incidents of real life) and arranging collaborative work among students. At each step of SB instruction, the educator should provide the students with equal opportunities to collaborate, express their opinions, practice, and reflect on their own performance and the performance of their peers. The study also reveals communication strategies that are the principal for novice teachers’ education. These strategies could underlie the basis of professional communication training, not only at university, but also at institutions delivering professional development training.