Abstract

The purpose of this study is to develop a measurement instrument to be used as an assessment tool of teachers’ development of conscientização (i.e., critical consciousness), defined as an individual’s ability “to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality”. After examining the different stages and components of conscientização, the author describes the process of generating initial items, determining the instrument’s format and content validity, and revising the instrument. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted with a diverse sample of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL), resulting in four internally consistent factors: (a) teacher beliefs about schooling and emotions towards inequality, (b) teacher as activists, (c) teacher awareness of local educational context, and (d) content selection and teaching strategies in the classroom. Psychometric properties of the scale are included.

1. Introduction

Critical pedagogy is a philosophy of education that encourages teachers and students to challenge common assumptions and question taken-for-granted ideologies in their local contexts. For teachers to support their students in such endeavors, teachers must have developed conscientização. (Conscientização has been translated from Brazilian Portuguese into English as “critical consciousness”, “conscientization” and “consciousness raising”. Freire, however, expressed preference for its use “in its Brazilian form, conscientização, and spelled that way” [1] (p. 24). Following Freire, I use the word conscientização in its original form throughout this article.) Conscientização, as conceptualized by the Brazilian educator, philosopher, and activist Paulo Freire, is a process of problematization, of “learning to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality” [2] (p. 35). When teachers have conscientização, they teach with a social justice orientation and are able to connect the school curriculum with the social, economic, cultural, historical, and political processes within which they and their students exist [3]. In the case of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) professionals, this connection must extend beyond their local context to include language ideologies in the global contexts (for a discussion of common English language ideologies, see [4]).

Despite the size of the literature on critical pedagogy and the now considerable number of studies of language teachers pursuing this approach (e.g., [5,6,7,8]), the research on its central concept of conscientização is scarce and has not been subject to basic ideas of measurement as a way of understanding it. While conscientização has been the subject of conceptual discussion and inquiry for decades (the earliest dating back to [9]), it was only recently that a few researchers designed a handful of quantitative instruments for its measurement [10,11,12,13]. This scholarship, however, stems from the fields of Counseling and Psychology, in the area of sociopolitical development and marginalized youth rather than from the field of (radical) education and adult literacy, where conscientização was originally conceptualized. Thus, while in the last five years, new scales to measure conscientização have been developed and validated, these scales have focused on marginalized youth—not on teachers.

In short, no instrument exists that was explicitly designed to measure the conscientização of teachers. Educators interested in assessing conscientização of teachers developed through teacher education programs could benefit from a scale that assesses conscientização development in pre-service as well as in-service teachers. In addition, an instrument explicitly designed to measure the conscientização of teachers has the potential to advance our understanding of conscientização and its effects in the classroom. Hence, the goal of this study was to design a new measurement instrument to be used with TESOL professionals. In this article, I describe the development of such an instrument, the Teacher Attitudes to Discrimination in Language Education Scale (TADLES), which examines the nature of in-service English language teachers’ critical consciousness, in particular their attitudes towards fairness and discrimination in education. In sum:

- Goal: To design a new measurement instrument to be used with TESOL professionals.

- Task: To detail the development of such an instrument, the Teacher Attitudes to Discrimination in Language Education Scale (TADLES).

2. Theoretical Framework: Critical Consciousness, or Conscientização

2.1. Stages of Conscientização

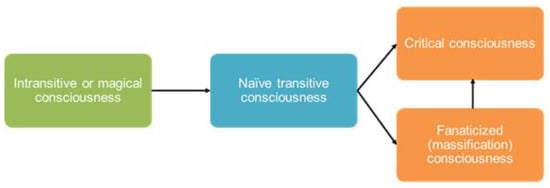

In his early work, Freire theorized conscientização as a process with a set of stages. The first stage is the intransitive or semi-transitive consciousness or magical consciousness. This stage is characterized by acceptance and resignation, where individuals fail to perceive many of the contemporary challenges. The second stage is naïve transitive consciousness, which is characterized by “an oversimplification of problems” [14] (p. 18), where individuals may see themselves as righteous and blame others for problems. Naïve transitive consciousness is important, because it is here where individuals are able to perceive unjust social power structures, investigate their causes, and “begin to be able visualize” alternatives [15] (p. 77). The outcome of this exercise should lead the individual toward the third stage, which is characterized by two opposing consciousnesses: conscientização (i.e., critical consciousness) and fanaticized (massification) consciousness (see Figure 1), the former being desirable [14] (p. 16). Fanaticized (massification) consciousness is a stage in which individuals are “more disengaged from reality”, which “leads to passivity, fear of freedom, and the loss of reflective action among the people” [14] (pp. 19–20). The opposing stage, conscientização or critical consciousness, is where individuals begin to understand causal principles of social injustice. While in the stage of naïve transitive consciousness, change “focuses on altering individual behavior”, in the critical consciousness, these changes focus “on systematic, structural, and normative obstacles” [14] (p. 39).

Figure 1.

The Movement between the Three Stages of Conscientização. Note. Adapted from Freire, P. (1959). Educação e atualidade brasileira [Education and present-day Brazil] (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Recife, Brazil: Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Copyright by the Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (1959).

It is worth noting, however, that these stages do not reflect “a progression through a finite series of steps with a fixed set of attitudes and behaviors to be achieved” [16] (p. 145) but rather are an ever-developing process that can overlap. The ever-developing and overlapping nature of these stages allow room for reimagining their boundaries, in particular, the boundaries within the desirable stage of conscientização or critical consciousness. That is because conscientização, as theorized by Freire, contains a broad spectrum of attitudes and behaviors. For example, it encompasses the beginning stages of an individual’s understanding of causal principles of social injustice [1] as well as the more complex stages, where individuals take actions against injustice at the individual and structural levels. With such a broad spectrum, I propose that the stage of conscientização be further divided into three states to help us observe and differentiate between the beginnings of an individual’s understanding, action being taken at the individual level, and action at the structural level.

2.2. Components of Conscientização

Following Freire’s definition of conscientização as the “learning to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality” [2] (p. 35), conscientização has been theorized to be composed of two main components: awareness and action. There have been attempts to test, explore, measure, and extend Freire’s concept of conscientização in several lines of research. Smith’s [9] was one of the first to operationalize conscientização and to exemplify how it can be manifested. Smith used drawings, questionnaires, games, music, simulations, questions, and open-ended interviews to stimulate “a wide range of [conscientização] related verbal responses” [9] (p. 5) from the different groups of Quechua-speaking indigenous peoples in Ecuador. This sampling resulted in a protocol that “relie[d] on a set of culture-specific visual stimuli and a standardized set of questions” based on three questions: “what is the problem?”; “what are the causes?”; and “what can be done about it?” According to Smith [9], each of these questions corresponds to one aspect of conscientização. The first, identifying the problem, corresponding to one’s ability to recognize the problem itself (i.e., naming); the second, contemplating about the problem, corresponding to one’s ability to reflect on its causes (i.e., reflecting); and the third corresponded to what could be done about the problem, referred to one’s intention to act to change it (i.e., acting). These three aspects (i.e., naming, reflecting, and acting) continue to be used today (albeit under different terms) and are the starting points for studies of conscientização.

While conscientização is believed to be a cognitive, higher-order disposition [17], emotion has always been present in Freire’s theory and writings as an important factor and he was far ahead of trends in Anglo-American social sciences. It is only since the 1990s that we have seen a turn to emotions in the field of general teacher development (e.g., [18,19,20]). In the field of language teacher development, following this turn, only recently has it gained attention (but see [21,22]). Freire warned, “We must dare so as never to dichotomize cognition and emotion” [14] (p. xxv). He continued, “We study, we learn, we teach, we know with our entire body. We do all of these things with feeling, with emotion and also with critical reasoning” [14] (p. xxv). Thus, to ignore emotion as a component of conscientização is to have an incomplete understanding of the role emotion occupies in teachers’ development process. Therefore, a new measurement scale targeted to teachers must include emotion as one of the components of conscientização.

3. Materials and Methodology: Development of the TADLES

3.1. Instrument

With the considerations discussed above, the TADLES was carefully theoretically grounded and items were developed based on social science theories (e.g., [23,24,25]) and questionnaire development procedures suggested by Brown [26], DeVellis [27], and Dörnyei and Taguchi [28]. The procedures consisted of five iterative steps:

- Clearly defining the construct.

- Generating initial items.

- Determining the instrument’s format.

- Determining the instrument’s content validity.

- Revising the instrument.

In the previous section, I defined the construct of conscientização, its stages, and components. In this section, I describe the other four steps.

A new measurement scale targeted to language teachers must include items that reflect not only the different components of conscientização and its different stages, but also a teacher’s awareness, reflection, emotion, and action in the specific contexts of language education, the school, and the classroom. One of the first scholars to identify and operationalize key elements of Freire’s ideas and practice for language teaching was Crawford [23] who presented a language curriculum theory based on 20 Freirean principles. These 20 principles were assorted into nine categories: the purpose of education, its objectives, the content of curriculum definition, learning strategies, learning materials, curriculum planning, teacher role, students role, and evaluation. Based on Crawford’s [23] principles of critical pedagogy curriculum design, several items were developed to provide insight into teachers’ beliefs and attitudes towards their roles, students’ role, and curriculum selection as well as to gauge teachers’ awareness of fairness and discrimination in education. Therefore, to assess awareness, items were adapted from Thomas et al. [13] and created by the author to reflect beliefs of fairness and discrimination in education and in society, fair treatment across social groups, and access to education across social groups. Items about teachers reflecting on their attitudes and beliefs about the purpose of education and about discrimination were adapted from Crawford [23] and created by the author. Aspects of emotion were measured by items adapted from Thomas et al. [13] that reflected empathy with social groups experiencing discrimination. Finally, to gauge teachers’ engagement in sociopolitical change (i.e., action component), items were created by the author to reflect potential action against social injustices at the individual as well as broader social level.

In addition to measuring specific components of conscientização in the contexts of education, school, and classroom, we need a scale that reflects the different stages of conscientização. This scale reflects five states as argued in the previous sections. The first state is the naïve state which is similar to Freire’s semi-intransitive consciousness or magical stage. In the naïve state, “one fails to perceive many of the reality’s challenges, or perceives them in a distorted way” (i.e., just world) [15] (pp. 75–76). The second state, the accepting state, is like Freire’s naïve transitivity stage in which individuals begin to recognize and question oppression and inequality, but either blame the system or feel things cannot be changed. The next three states together are equivalent to Freire’s conscientização or critical consciousness and each delimits a set of attitudes and behaviors within it. For example, in the third state, the critical state, individuals become more aware of issues of equity and recognize “things and facts as they exist empirically, in their causal and circumstantial correlations” [29] (p. 39). The agentive state, or fourth state, includes some form of personal action (at the individual level) in response to oppression or inequity. Lastly, the fifth and final state, the transformative state, includes some form of action in the broader social context in response to oppression or inequity (e.g., encouraging others into acting for change). Therefore, for every item related to a component, a set of five items were written—each item reflecting one of the five states. For example, one item related to awareness becomes a set of five items (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Example of a set of items related to awareness in Guttman scale format.

A Guttman scale format (a type of question structure in which items can be ordered hierarchically) and a Likert-type scale were selected as the instrument format for the survey items. Items were written as a set and ranked in order of “endorsability” in a “cumulative manner” [30] (p. 260). That is, when a participant agrees with any specific item within the set, they would also agree with all previous items. Table 1 provides an example, when a participant agrees with item 4, it is implied that they also agree with items 3, 2, and 1. The idea that items can be written in a sequential approach “with each earlier item subsumed by later items” [13] (p. 491) is particularly useful for investigating a construct with a developmental aspect such as conscientização because of its conceptualized states. By using a Guttman scale, items can be written in a sequential pattern which allows the results to be presented by different states of conscientização.

Since this instrument was developed for use with TESOL professionals from different countries of origin, attention was taken to write items that were clearly worded. The initial items were written at a 10th grade reading level, according to the Flesch–Kincaid statistic of 10.5. To determine the instrument’s content validity, the initial items were piloted with a panel of eight experts from different countries of origin. Six of the experts were “content experts” (i.e., professionals who have published or worked in the field of applied linguistics and are familiar with the concept of critical consciousness) who were invited based on my familiarity with their scholarship on critical pedagogy. Two of the experts were “lay experts” (i.e., peers who are not familiar with the field of applied linguistics or critical pedagogy) who were invited based on my personal connections. Experts were instructed to provide feedback on different aspects of the items’ content; namely the items’ comprehensiveness, clarity, specificity, fairness, and pertinence, and to ensure that the items reflected the respective component under which each was included. Experts were also provided with guidelines to assist them in the review process. Items were revised based on the experts’ feedback and the revised version was then shared with four peers, junior scholars (also in the field of critical applied linguistics) for feedback on the items’ appropriateness, wording, and relevance. The items were once again revised and the final items reflected 19 sets of five items per set and one set of six items, totaling 101 items in a Guttman scale format on a five-point Likert-style scale (1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, 5 = strongly agree).

3.2. Sampling Strategy

Self-administered, electronic written surveys were distributed via mailing lists and social media to several national and international English language teacher professional organizations (e.g., TESOL, IATEFL) and respective special interest groups (SIGs) as well as through purposeful snowball sampling and personal contacts. Before administering the surveys, institutional review board approval was obtained for the data collection procedures involving human subjects.

3.3. Participants

The entire sample consisted of 76 in-service English language teachers representing a total of 22 different countries of origin (with 33% originating from the U.S.) with more female (67%) than male participants (30%) plus 1% gender fluid and 1% who preferred not to answer. Participants ranged in age from 23 to 81, with a mean of 40.2 years. The teachers’ years of teaching experience ranged from just a few months to 36 years, with a mean of 12.8 years. Six (8%) of them had three years or less of experience, 26 (34%) had between four and nine years of experience, 27 (36%) had between 10 and 19, 10 (13%) had between 20 and 29 years of experience, and five (7%) had 30 or more years of teaching experience; two (3%) did not answer. Of those who indicated their highest level of education, 17 (22%) had completed a doctorate degree, 41 (54%) a master’s degree, and 6 (8%) had the equivalent to a bachelor’s degree; 8 (11%) did not answer. In addition, 15 (20%) had completed certificate-level training (e.g., CELTA).

3.4. Procedure

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to explore the relationships (i.e., covariance) among the items (i.e., variables) and to find common, underlying constructs (i.e., latent variables) within them [27,31] SPSS 25 was used for EFA. EFA assumes a set of assumptions: (a) adequate sample size; (b) correlation between variables and factors; and (c) the absence of multicollinearity. To verify the assumption of sampling adequacy, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted. The KMO is a post hoc analysis that measures the sampling adequacy and can be calculated for an individual as well as multiple variables. Bartlett’s test of sphericity measures whether the correlation matrix has the same or different values as an identity matrix. To test the assumption of correlation, items must group properly into factors and there must be some level of correlation among them. Tabachnick and Fidell [32] recommend eliminating items with low values of correlation (<0.3) and with values too high (>0.8). Finally, to test the linearity among variables, factors were rotated after extraction.

To determine the number of factors to retain, a combination of criteria was used [33]. Six common techniques [34] were used to determine the number of factors to extract. In order of application, the techniques were:

- The Guttman–Kaiser rule (K1).

- Cattell’s scree test.

- Elimination of non-trivial factors.

- Elimination of complex items.

- A priori criteria.

- The percent of cumulative variance.

Lastly, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to check internal consistency as well as the internal consistency of each of its factors.

4. Results: Exploratory Factor Analysis

Analysis of the correlation matrix displayed many correlation coefficients of 0.3 and above in this study, as recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell [32]. Nine items were dropped because of relatively low correlations with other items. Pearson’s critical correlation value was used for a significance level of α = 0.025 with n = 70 for a two-tailed test (r = 0.232) to establish items with low correlation values. Therefore, nine items which had less than 95% of r < 0.232 were dropped. An EFA on the 92 remaining items was then conducted.

To test the linearity among variables, I followed Tabachnick and Fidell’s [32] suggestion and ran a four-factor EFA followed by a direct oblimin rotation. As shown in Table 2, the highest correlation coefficient was 0.274, and since none of the correlation coefficients exceeded the threshold of 0.32, I used an orthogonal rotation (varimax) instead.

Table 2.

TADLES component correlation matrix.

Higher scores on the TADLES indicate a more developed state of conscientização in language education. The scores for participants in this study ranged from 260 to 462, with a mean score of 368.13 (SD = 67.88). Participants’ attitudes towards fairness and discrimination in education were highest for item Q101, “I believe a good teacher is a learner, and I try to learn from/with my students” (M = 4.66, SD = 0.58). Item-specific mean was lowest for item Q08, “I am aware of existing discrimination where I live” (M = 1.62, SD = 0.855).

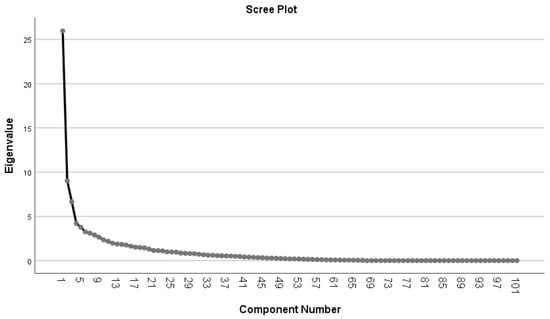

The K1 initial analysis yielded 23 factors with eigenvalues greater than one, explaining 83.34% of the variance in the participants’ scores on the scale. Cattell’s scree test suggested that factors 1, 2, and 3 were distinct; however, interpreting the “break point” was ambiguous (see Figure 2). Due to the variance in the number of possible factors that could be extracted, two-, three-, four-, five-, and six-factor solutions were examined. The five- and six-factor solutions presented factors with less than three items above the cut-point of 0.5 and were therefore eliminated. Variables that correlated to more than one factor and with loading higher than 0.4 (i.e., complex items) were eliminated. This analysis resulted in a four-factor solution that corresponded to a priori criteria of four potential subscales (awareness, reflection, emotion, and action). The four factors accounted for 15.25%, 13.68%, 10.72%, and 7.40% of variance, respectively with a cumulative explained variance of 47.04% (see Figure 2). To evaluate the relationship between the variables in each construct, Cronbach’s alpha was used to demonstrate internal consistency of the TADLES and of each of the rotated factors. The results demonstrate strong internal consistency (α = 0.954) for the TADLES. Table 3 presents the alpha reliability for each factor.

Figure 2.

TADLES scree plot of a four-factor rotated solution.

Table 3.

TADLES factors’ reliability statistics.

Factor 1 comprised 17 items. This subscale explained 15.25% of the total variance of the instrument. Table 4 shows the factor loading and communality for each item in factor 1. Factor 1 returned a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.908. (Reliability scores were assessed for each factor and were reasonably high. Acceptable Cronbach’s α scores range from 0.70–0.95.) Items in factor 1 combined items from all four constructs (i.e., awareness, reflection, emotion, and action) and four of the five statuses (i.e., naïve, accepting, critical, and agentive). Seven of those items were adapted from Thomas et al. [13]; four of them were initially conceptualized as the construct awareness, and three were initially conceptualized as the construct emotion. Ten items with loadings in factor 1 were newly created: eight items were based on Crawford [23] initially conceptualized as reflection, and two were based on the critical consciousness literature initially conceptualized as action. While it may seem that these items do not fit together, a closer look may explain why they loaded together. One assumption is that, for these participants, awareness is manifested in action, and that the latter does not occur without the former. For example, the awareness of “the world [being] unfair for some people” may manifest in the action of “mak[ing] sure that students are treated fairly”. For practical purposes and assisting with the analysis, factor 1 was named “teacher beliefs about schooling and emotions towards inequality”.

Table 4.

TADLES Factor 1 Items, Loadings, and Status.

Factor 2 consisted of 14 items. This subscale explained 13.68% of the total variance of the instrument. Table 5 shows the factor loading and communality for each item in factor 2. Factor 2 returned a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.933. The 14 items also represent all four domains (i.e., awareness, reflection, emotion, and action). Eight of those items were based on Thomas et al. [13] with six initially conceptualized as the construct awareness and two initially conceptualized as emotion. Six of the 14 items were newly created; three based on Crawford [23] related to action; two based on the literature regarding action; and one based on the literature regarding reflection. Again, the items loaded in factor 2 did not seem to go together; however, it may be that, for these participants, action manifests in conjunction with reflection which in turn manifests in conjunction with awareness. In addition, it may be that for these participants, emotion, on the other hand, manifests in conjunction with and across all constructs. Further, all items loading in factor 2 reflected the statuses agentive and transformative, indicating that for these participants there may be no distinction between action for change at the individual level and in the societal level.

Table 5.

TADLES Factor 2 Items, Loadings, and Status.

Except for one item (on co-creating curriculum), factor 2 items had in common the theme of “discrimination” and experts’ factor-naming suggested “discrimination” and “activism” as underlying constructs. Because every item in this factor reflected an action-oriented status (i.e., agentive and transformative), it may be that for these participants the challenge of discrimination goes beyond the awareness of its existence and is closely tied to acting against it. A teacher who acts against discrimination shows a developed conscientização in this area. This is a teacher who sees acting and promoting action against discrimination as part of their role as a teacher for social justice both within and outside their classroom. This is a teacher who understands that they must “operate as activists in broader struggles for social transformation” [35] (p. 214, see also [36]). This is a teacher who has a desire to act transformatively [37] and a commitment to empowering students and in making social change at the micro (i.e., classroom) as well as macro (i.e., society) levels. Factor 2 was tentatively named “teachers as activists”.

Factor 3 comprised ten items. This subscale explained 10.72% of the total variance of the instrument. Table 6 shows the factor loading and communality for each item in factor 3. Factor 3 returned a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.876. The items were initially conceptualized as the components awareness and action. Seven of the nine items were based on Thomas et al. (2014) and reflected the initial component awareness. The other three were newly created items based on Crawford [23]; two reflected the initial component awareness and one action. The findings from this exploratory factor analysis suggest that the items measuring the constructs awareness and action measure similar concepts. Perhaps the participants in the current study did not differentiate between the two constructs and, therefore, these constructs were grouped together.

Table 6.

TADLES Factor 3 Items, Loadings, and Status.

Additionally, items loading in factor 3 primarily reflected the statuses naïve and accepting, with two exceptions. Although “I believe education is political; it reflects the interests of certain social groups” had been initially conceptualized as an indicator of a critical status, it is possible that it was tapped into participants’ idea of accepting. It may be that for these participants awareness does not necessarily mean being critical, because the quality of awareness can be manifested either by the acceptance of things as they are or by the intentionality to act and change the status quo. The same can be said of item “I believe education does not give everyone a fair chance to do well.” Although it had been initially conceptualized as an indicator of a critical status, it is possible that it tapped into participants’ idea of accepting.

Most experts’ factor-naming suggestions for factor 3 had “education” as a common, underlying theme. Except for two items, all the others referred to just world/education beliefs. Beliefs about education being fair and reflecting fair treatment across students from different social groups are the opposite of those from teachers for social justice. The very foundation of education for social justice is laid on the belief that education is a deeply civic, political, and moral practice [38]. Education as a political, interested, and biased social activity [2] seeks to help students see the injustices and inequalities in their lives, act in opposition to oppression, become responsible citizens, and develop conscientização. Factor 3 was thus named “awareness of local educational context.”

Factor 4 comprised six items. This subscale explained 7.40% of the total variance of the instrument. Table 7 shows the factor loading and communality for each item in factor 4. Factor 4 returned a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.794. All items loaded in this factor were newly created items based on Crawford [23] and had been initially conceptualized as the construct reflection. Items loading in factor 4 reflected the statuses critical, agentive, and transformative. The three items indicating critical status in factor 4 seem to have a different quality from the one item also indicating critical in factor 3. That is, if the quality of awareness can be manifested either by the acceptance of things as they are or by the intentionality to act and change the status quo, then it seems that participants understood these three items as closely aligned with the intentionality to act and change the status quo. Many of the items loaded in factor 4 were related thematically to beliefs of curriculum design, in particular teacher’s role, and content definition. They were also related to beliefs of the teacher’s agency in the classroom.

Table 7.

TADLES Factor 4 Items, Loadings, and Status.

In addition, items in factor 4 seem to have in common the place classroom. The classroom refers to much more than just a physical space or a workplace. The classroom is the place of a teacher’s professional practice. The classroom is the place where teachers can (potentially) be themselves. It is where teachers can connect and communicate with students. The classroom is a rich ecosystem of relationships among students and between students and teacher. It is also the place where a teacher can control their practice and (often) exercise agency regarding decisions related to their approach and content selection. In factor 4, the approach and content selection refer specifically to incorporating, discussing, and handling controversial issues, personal opinions, and life experiences in the classroom. The approach of bringing the outside world (i.e., current topics, students’ interests) into the inside world (i.e., classroom) is particularly related to Freire’s notion of “generative themes” [39] (p. 47) and of connecting lived experiences to the classroom. English language teachers who teach for social justice take advantage of topics brought into the classroom by and of interest to the students (i.e., outside world) and use these as a springboard for problematizing [40] such topics’ notions of common sense. In other words, these teachers put the classroom context into the wider social context and understand that what happens in their classroom should have consequences in different contexts outside the classroom [41]. Factor 4 was named “content and strategies in the classroom”.

5. Limitations and Future Research

Conscientização is a complex concept that can be only partially captured through quantitative methods. I have addressed this limitation in the development of the original, larger study which combines quantitative and qualitative research approaches (i.e., mixed research design) (see [5]). (This study provides this author’s original data and it incorporates over 300 references related to research data on grounds of TADLES approach and method.) While the development of a scale to assess the development of language teachers’ conscientização adds to the literature on language teaching for social justice, this study is not without its limitations.

Given that the data relies on self-report measures, the potential effects of social desirability and social approval [42] bias must be considered. In addition, because of the length of the instrument, fatigue must also be taken into account. While the researcher has no control over the reliance on self-report nature of measures such as this nor over the potential effects of social desirability, shorter instruments can be developed. Since the four factors have now been extracted and named, these could be used as subscales and, therefore, shorter measurements.

Despite these limitations, the TADLES is an important contribution to the field of conscientização and of language teaching for social justice. There are only a handful of scales designed specifically for the measurement of conscientização and the TADLES is the only one designed for the teacher population. That being said, future research should further validate, and perhaps even expand, the TADLES. The TADLES could be expanded by including items related to critical language awareness and ideologies (e.g., [43,44,45]). Furthermore, when developing a measurement instrument and using EFA, it is ideal to follow with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). However, doing a CFA is dependent on having a sufficiently large dataset [46] which was not the case with the present study. Further development of the TADLES should include larger sample sizes to allow researchers to carry out CFA.

Research is needed to assess the efficacy of social justice-oriented language teacher education programs designed to promote and facilitate conscientização. The TADLES has the potential to help us better understand teachers’ development of conscientização and its effects in the classroom. Because an instrument such as this provides only a time- and space-bound portrait of the participants’ state of critical consciousness, a longitudinal study, where the TADLES is administered to pre-service teachers during different milestones (e.g., first-year teacher education program, during practicum, and before graduation), can help us better understand how conscientização develops and operates over time. Thus, the TADLES can be used as an instrument for teacher educators and researchers with a social justice orientation to build teacher education programs to help promote and support the development of teachers’ conscientização. When teachers develop conscientização, they become aware of “social, political, and economic contradictions” [2] (p. 35) and take action against social injustices in education and their classrooms.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided by fellowships from the Bilinski Educational Foundation and the Soroptimist International Founder Region.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the principles of the Nuremberg Code, the Belmont Report, the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the teachers who participated in this study for their availability and willingness. Additionally, thank you to the panel of eight experts who provided feedback during the instrument design and to Patharaorn Patharakorn for her assistance in data collection and data analysis. Lastly, thank you to this Special Issue editor, reviewers, and authors for their suggestions and feedback on preparing this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Freire, P. Conscientisation. CrossCurrents 1974, 24, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, L.E.; Apple, M.W. The Curriculum: Problems, Politics, and Possibilities, 2nd ed.; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah, A.S. The politics of English language teaching. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2nd ed.; May, S., Hornberger, N.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, P. Becoming and Being a Critical English Language Teacher: A Mixed-Methods Study of Critical Consciousness. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hawai’i, Manoa, HI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, P.; Crookes, G.V. “Most of my students kept saying, ‘I never met a gay person’”: A queer English language teacher’s agency for social justice. System 2018, 79, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parba, J.; Crookes, G. A Filipino L2 Classroom: Negotiating Power Relations and the Role of English in a Critical LOTE/World Language Classroom. In International Perspectives on Critical Pedagogies in ELT; López-Gopar, M., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G.B. Doing critical pedagogy in neoliberal spaces: Negotiated possibilities in Korean hagwons. In Readings in Language Studies; Miller, P.C., Ed.; International Society for Language Studies: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2014; Volume 4, pp. 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W. The Meaning of Conscientização: The Goal of Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy; Center for International Education of the University of Massachusetts: Amherst, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer, M.A.; Rapa, L.J.; Park, C.J.; Perry, J.C. Development and Validation of the Critical Consciousness Scale. Youth Soc. 2017, 49, 461–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, E.H.; McWhirter, B.T. Critical Consciousness and Vocational Development among Latina/o High School Youth. J. Career Assess. 2015, 24, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, R.Q.; Ezeofor, I.; Smith, L.C.; Welch, J.C.; Goodrich, K.M. The development and validation of the Contemporary Critical Consciousness Measure. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.J.; Barrie, R.; Brunner, J.; Clawson, A.; Hewitt, A.; Jeremie-Brink, G.; Rowe-Johnson, M. Assessing Critical Consciousness in Youth and Young Adults. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to Those Who Dare Teach; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation; Bergin and Garvey Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P. Education, Literacy, and Humanization: Exploring the Work of Paulo Freire; Bergin & Garvey: Westport, CT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Podger, D.M.; Mustakova-Possardt, E.; Reid, A. A whole-person approach to educating for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, R.L. The Passionate Teacher: A Practical Guide; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. The emotional practice of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1998, 14, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P.; Jeffrey, B. Teachable Moments: The Art of Creative Teaching in Primary Schools; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Benesch, S. Emotions as agency: Feeling rules, emotion labor, and English language teachers’ decision-making. System 2018, 79, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golombek, P.R. Redrawing the Boundaries of Language Teacher Cognition: Language Teacher Educators’ Emotion, Cognition, and Activity. Mod. Lang. J. 2015, 99, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L.M. Paulo Freire’s Philosophy: Derivation of Curricular Principles and Their Application to Second Language Curriculum Design. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (7911991). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Ann Harbor, MI, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Crookes, G.V. Critical ELT in Action: Foundations, Promises, Praxis; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Educação e Atualidade Brasileira (Education and Present-Day Brazil). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, 1959. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.D. Using Surveys in Language Programs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Taguchi, T. Constructing the questionnaire. In Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 11–57. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Education for Critical Consciousness; Continuum: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, P.H.; Wright, J.D.; Anderson, A.B. Handbook of Survey Research; Academic Press: New York NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Meehl, P.E. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol. Bull. 1955, 52, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld, T.; van Hout, R. Statistical Techniques for the Study of Language and Language Behaviour; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.D. Choosing the right number of components or factors in PCA and EFA. Shiken JALT Test. Eval. SIG Newsl. 2009, 13, 19–23. Available online: http://jalt.org/test/PDF/Brown30.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Ginsburg, M.B. Ideologically informed conceptions of professionalism. In Contradictions in Teacher Education and Society: A Critical Analysis; Falmer Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1988; pp. 129–164. [Google Scholar]

- Picower, B. Practice What You Teach: Social Justice Education in The Classroom and The Streets; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abednia, A. Teachers’ professional identity: Contributions of a critical EFL teacher education course in Iran. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H.A. Rethinking Education as the Practice of Freedom: Paulo Freire and the Promise of Critical Pedagogy. Policy Futures Educ. 2010, 8, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, I. When Students Have Power: Negotiating Authority in a Critical Pedagogy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Abednia, A. Transformative L2 Teacher Development (TLTD): A tentative proposal. In Power in the EFL Classroom: Critical Pedagogy in the Middle East; Wachob, P., Ed.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2009; pp. 263–282. [Google Scholar]

- Baynham, M.; Roberts, C.; Cooke, M.; Simpson, J.; Ananiadou, K.; McGoldrick, J.; Wallace, C. Effective Teaching and Learning in ESOL: Summary Report; Institute of Education, University of London: London, UK, 2007; Available online: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/22304/2/doc_3379.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2016).

- Huang, C.-Y.; Liao, H.-Y.; Chang, S.-H. Social desirability and the clinical self-report inventory: Methodological reconsideration. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 54, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Critical Language Awareness; Longman: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, O. Multilingual language awareness and teacher education. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education; Cenoz, J., Hornberger, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, E.W. Awareness of Language: An Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gagne, P.; Hancock, G.R. Measurement Model Quality, Sample Size, and Solution Propriety in Confirmatory Factor Models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2006, 41, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).