Abstract

Leadership plays a central role in improving and sustaining quality in Early Childhood Development (ECD) settings in the South African context. This article explored the leadership of the Inclusive Education Policy (IEP) and the challenges experienced by ECD centre managers and teachers. Children with disabilities are most vulnerable, marginalised, and denied access to early education, especially in rural communities. Grounded in Bronfenbrenner’s ecosystems theory, the study adopted a qualitative approach. The participants included three centre managers and three teachers from Early Childhood Development centres in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. The findings revealed that most participants had minimal knowledge and understanding of the policy and its implementation. There was also a lack of leadership from the policymakers to ensure that the IEP was monitored, supported, and implemented. Our recommendations are that all ECD practitioners receive appropriate training and development on the policy, ongoing support and guidance in implementing the policy, and proper resources for their centres and playrooms (financial, physical, and human resources).

1. Introduction

Research finds that leadership is one of the single most important drivers of organisational performance, quality improvement, and innovation [1,2,3]. This suggests that effective leadership is important and necessary in implementing ECD policies. There is a growing interest in better understanding how ECD leadership can positively impact policy implementation and improve quality [1]. To ensure that all learners benefit from quality education and access, the Department of Education (DoE) developed the policy Education White Paper 6 (WP 6)—Special Needs Education: Building an Inclusive Education and Training System [2] to accommodate all learners in schools. In South Africa, special needs education, especially in Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE), is mostly neglected [3]. In this article, the authors will refer to the policy as IEP/WP6, since more teachers are familiar with this nomenclature. The accepted nomenclature for leaders in ECD centres is centre managers, and teachers are called practitioners. The reason teachers are called practitioners is due to their qualifications. Most teachers in ECCE centres are unqualified or underqualified as per the norms and standards of educators in South Africa.

The implementation of the IEP/WP6 is not compulsory for pre-Grade R or ECCE [2]. Yet, early intervention in the disabilities would yield better chances for remediation. According to Storbeck and Moodley [4], the early years of a child’s life reinforce all expected growth in the areas of socio-emotional, linguistic, and cognitive domains. Learning begins at birth; therefore, laying a solid foundation in the development and growth of young children is essential and should embrace all children, including those with disabilities [5]. According to Landsberg, Kruger, and Swart [6], all teachers must be trained to identify and intervene to support young children with their challenges. It is one of the responsibilities of teachers to ensure that every child has the right to care and support. Children of all ages are catered for and accommodated in the Child’s Rights section in the Constitution. Section 29(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996) provides that “every child has the right to basic education” [7]. Although every child has the right to basic education, this phenomenon is not evident in ECCE centres regarding the implementation of IEP/WP6. According to the DoE [2], the IEP/WP6 identifies compulsory support for children from seven to 18 years of age.

The leadership role in ECD centres would thus be essential in the implementation of the IEP/WP6. It has been identified that successful inclusion was dependent on the actions of centre managers [3,8], as they created a culture of inclusion and could challenge or support inclusion [9]. According to Bornman and Rose [10] (p. 7), “general lack of support and resources, as well as the prevailing negative attitudes toward disability” were obstacles in the implementation of the IEP/WP6. Thus, it remains to be seen whether the ECD centre managers have realised the importance of the IEP/WP6 in the development of babies, toddlers, and young children.

Children with disabilities, especially in rural communities, experience great difficulty in gaining access to education. Very few special needs schools exist for ECCE (birth to four-year-olds), and they limit the admission of learners. Due to abject poverty and lack of financial resources, most learners in rural communities are often denied access to special needs schools. Anonymous and Anonymous [11] state that conflicting policies could be the reason for unpromising policies in the context of South Africa that threaten disarray rather than progress in the ECD sector. Donohoe and Bornman [3] confirm that South Africa’s inclusive education policy is characterised by high conflict and ambiguity. Placing a policy in an agency where it conflicts with existing policies and goals leads to fewer resources, little support, and almost certain non-implementation. This may be a contributing factor to the lack of progress in the implementation of the Inclusive Education Policy. Within the Department of Education, various sectors compete for limited resources, which impacts ECCE centres; since resources need to be equitably distributed. The current educational drives are in the expansion of Grade R (equivalent to kindergarten) and basic adult education programmes, with significantly fewer resources being dedicated to inclusive education in ECCE centres [12].

This article aims to contribute to the following research questions:

- What are the centre managers and teachers’ knowledge and understanding of inclusive education policy?

- What are the challenges that limited the implementation of the IEP/WP6 in South African ECD playrooms/centres?

- What is the role of the Department of Education in implementing the Inclusive Education Policy in Early Childhood Education and Care playrooms?

2. Literature Review

Due to South Africa’s call for a more play-based pedagogy for birth to four-year-old children, the word “playrooms” is used to describe the playful environments at the ECD centres. This article focuses on the implementation of IEP/WP6 in the ECCE centres and playrooms in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa, focusing on children from birth to four years. Due to the major drive for a play-based pedagogy in ECD classrooms, the term playroom is used to describe the environment in the ECD centre. The aim is to explore the perceptions of centre managers and teachers in implementing IEP/WP6 in their playrooms/centres in the OR Tambo Inland Education District. Researchers agree that the future of Africa lies with the well-being of its children and youth [13].

IEP/WP6 is a policy that encourages the system to accommodate all learners irrespective of their abilities or disabilities [2]. The implementation of the policy should start at an early level in education, namely birth to four years. Bastable and Dart [14] state that young children undergo optimal development during this period, and if not supported effectively, the consequences can be distressing. The IEP/WP6 policy aims to ensure that all children are given the necessary support for optimal development. This policy is aimed at guaranteeing equal access and schooling for all young children regardless of race, age, gender, colour, and capability [15]. Although the policy clearly articulates what has to be done, centre managers and teachers are experiencing many challenges.

2.1. Accommodating Inclusive Education in Early Childhood Care and Education Centres

IEP/WP6 has become a central issue in educational practice worldwide [16]. For the DoE, the implementation of IEP/WP6 in schools is seen to eliminate unfair practices and accommodate all young children irrespective of their unique needs [2]. Inclusive education has different meanings in different countries, especially in terms of practice and implementation. In some countries, the implementation of inclusive education is aimed at helping young children succeed despite their developmental barriers. IEP/WP6 implementation is a vibrant procedure of modifying and accommodating the special needs of all children, irrespective of the social background, race, colour, or creed [2].

The implementation of IEP/WP6 is beneficial for all young children from birth to four years with or without disability and teachers, parents and families, childcare providers, professionals, and society [17]. According to Nind, Flewitt, and Payler [18], the environment enables all children in learning centres, with or without special needs, to develop their functional-social capacities. According to Ebrahim [16], this policy is viewed as the most equitable and just approach for educating young children with or without developmental disabilities.

Nel, Müller, and Rheeders [19] argue that the effective implementation of IEP/WP6 depends on the high quality of professional support, the commitment of relevant stakeholders, and appropriate resources (physical and human). This support should equip teachers and centre managers with the necessary skills required to implement the policy. Swart and Pettipher [20] consider teachers and centre managers to be a vital force in determining the quality of implementing policy in the centres. ECCE teachers are key figures in successfully implementing the policy with children aged birth to four years. The Department of Education expects all teachers to have a sound knowledge and understanding of the implementation of the inclusive education policy [21]. Unfortunately, many untrained or poorly trained teachers and centre managers in this sector implement IEP/WP6 [16]. However, the authors believe that the leadership roles from the Department of Education were not sufficient, and the ECD sector was neglected as they do not form part of the educational system as yet. The educational system in South Africa begins from Grade R to matriculation levels (kindergarten to the final year of schooling). Hence, qualified teachers are rarely found in the ECD sector in South Africa. Walton and Ruszynak [17] support this when they point out that there are teachers who were willing to pursue their skills-development need to be trained in a range of issues so that their contributions could be of value in the ECCE centre.

Studies by Lambert, Jomeen, and McSherry [22] on inclusive education have shown teachers and centre managers were often faced with numerous challenges of teaching learners in an all-inclusive class. Teachers lack the skills and knowledge required to deal with an all-inclusive class. Sokal and Katz [23] assert that teachers and centre managers need to have the appropriate knowledge, skill, and understanding of inclusive education for adequate support to special needs children. They also need the necessary resources for optimal teaching and learning. However, Mugweni and Dakwa [24] argue that it is impossible to train all teachers and centre managers who will take care of learners with barriers to learning as inclusive education specialists.

2.2. Role of the Department of Education for Effective Implementation of IEP/WP6

The roles and responsibilities of the different levels of support at the Department of Education are not clarified in the policy for the effective implementation of IEP. The key to the successful implementation of an inclusive education policy is that teachers will need time, ongoing support, and in-service training. Thus, change requires a long-term obligation to professional development [25]. Gregory [26] argues that most teachers are competent but lack the understanding of IEP/WP6, thus causing a challenge to implement it successfully in schools. The catalysts of the policy implementation, namely intervention by officials from the DBE, have not realised the urgency to train and support teachers effectively in the implementation of policies.

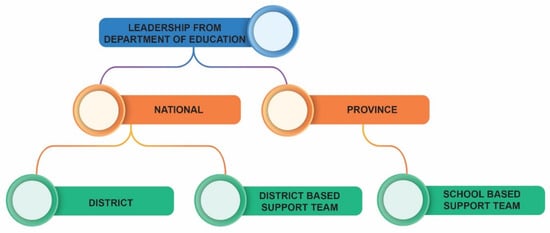

Figure 1 illustrates the support levels from the Department of Education in South Africa in relation to the structures created for the effective implementation of IEP/WP6.

Figure 1.

Levels of leadership from the Department of Education (adapted from Inclusive Education Workshop Handout, 23 March 2013).

2.2.1. Leadership from National Level

According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory (2009), the exosystem can be related to the national level, where policies are discussed, consulted, and agreed upon for their development. Once developed at this level, provinces are provided with guidelines on how to implement the identified strategies [2]. Provinces are first trained on these policy imperatives before they are implemented at the school level. According to Gregory [26], IEP/WP6 was made available to all provinces and schools. Due to certain unforeseen issues, provincial curriculum advisors and teachers were not informed or trained on how to implement this policy. This policy was distributed to schools which caused a major challenge and surprise to many ECCE teachers. They felt incompetent to teach children with disabilities in mainstream classrooms. They were also not supported by their respective Provincial or District offices to implement the policy effectively.

2.2.2. Leadership from Provincial and District Level

Provinces are responsible for supporting schools with all the necessary policies and implementation procedures [27]. The decisions made at the provincial level regarding learners with disabilities in ECCE centre directly influence these children’s teaching and learning. It is the responsibility of the provinces to ensure that teachers are appropriately trained and have the available resources to manage learners with disabilities in their mainstream ECCE centres. The province is also responsible for monitoring the implementation of policies in ECCE centres. Studies have shown that the subject advisors or district officials do not monitor most ECCE centres. ECCE centres are often left on their own to function [25].

Within this system, challenges such as lack of human and financial resources and appropriate monitoring and support systems can indirectly affect teachers’ implementation of IEP/WP6. For example, the lack of evaluation and inadequate monitoring and support of the School-Based Support Team (SBST) as explained in WP6 might lead to inappropriate support for teachers in responding to learners’ barriers in the playroom [28]. At this level, the province is responsible for ensuring that clear guidelines are in place for the districts to coordinate and support schools. However, Jaeger and Bowman [27] indicate no appropriate systems to support and monitor the effective implementation of IEP/WP6 in ECCE centres.

The kind of support teachers receive from the District level may directly influence how they implement the policy at the classroom level. According to the DoE [2], the District-Based Support Team (DBST) should support the School-Based Support Team (SBST) in coordinating learner and teacher support in all schools. Every district should establish the DBST and schools within the district must be supported by a team of officials. The primary function of the DBST will be to evaluate and support the SBST to ensure that all children, irrespective of their disabilities, receive quality teaching and learning in mainstream schools in ECCE centres [5].

The DBST should ensure that every school establishes an SBST which will coordinate both learner and teacher support. The DBE has systems to ensure support to teachers [29,30]. However, many teachers feel that they still do not receive enough professional development and support to meet the challenges of their learners in the ECCE playrooms. The poor support at the district level compromises service delivery at schools at large and often creates gaps in teaching and learning, thus leading to poor performances of learners with disabilities [3].

3. Theoretical Framework

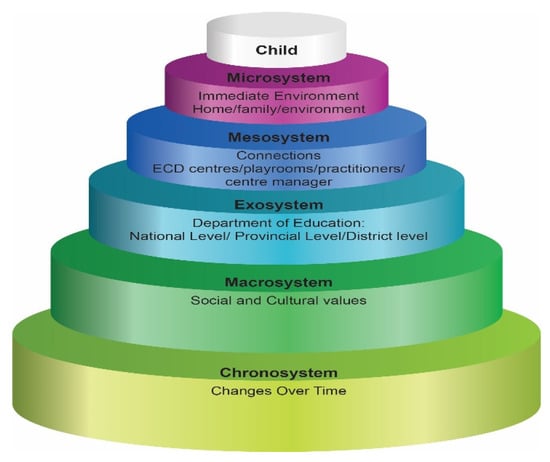

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory is most appropriate for this study and has five layers within which the child is the central figure. The systems included are the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. This theory is relevant to the study because a child does not exist as an individual in an environment but rather as part of a whole system. The child will need the support of everyone in the community, starting from the surroundings such as parents, siblings, the community as a whole, and all the stakeholders of the community at large. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model highlights the importance of the different stakeholders’ contributions to the child’s life. All systems are integrated and play a significant role in ensuring that children in the ECCE playrooms are given access to quality education, accommodated, and accepted for being different, acknowledging their abilities and disabilities and ensuring that fundamental rights are not neglected. Figure 2 illustrates the theoretical framework and how it relates to the study.

Figure 2.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory and its relation to the implementation of IEP/WP6.

According to Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, the microsystem layer is the child’s immediate environment representing the child’s nuclear family; for instance, a child learns a language, values, and respect from the family. According to Bronfenbrenner [31], the microsystem is the first and closest level, representing the developing child where relationships with people close to the child, such as parents, siblings, friends or peers, teachers, and caregivers, are formed.

The mesosystem is the second layer of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, representing the reciprocal interaction of different microsystems in a developing child’s life [31]. The mesosystem connects the two environments, the immediate and the indirect environments of the child. Both the mesosystem and microsystem will inform the development and introduction of the child to the social and cultural values. Bronfenbrenner regards this level as important. He believes a child collaborates two unrelated microsystems and is expected to transit from one system to another [31]. According to Krishnan [32], a disconnection in collaborating with different system levels affects outcomes in the reaction and response to the learning of a developing child.

According to Bronfenbrenner, the home (microsystem) plays a significant role in the early development of the young child [31]. During the ages from birth, the first four years, the family plays a significant role in the child’s social, emotional, cognitive, and intellectual development. This is an overtly sensitive period for the young child’s future development. A positive experience for the child will ensure that they are well adjusted to being embraced in the mesosystem (school). In the mesosystem, the teacher plays another significant role in the young child’s life, similar to the parents. The influence of the teacher also has a lasting impact on the young child’s lifeworld.

The exosystem is where the Department of Education and the various levels exist. The impact of this layer on the meso- and microsystem is crucial in the implementation of effective inclusive education strategies. This middle layer either assists in the development of the child, or it could lead to the child’s neglect if there is no proper training, monitoring, and support from the Department of Educations and the various levels and structures as created for the implementation of the IEP, especially in ECCE centres. National policies, protocols, and support play a significant role in the delivery of ECD services and interventions. The National Government has a major role to play in supporting the health, education, and rights of all children. There is a need for acknowledgement and financial support to accommodate children with disabilities in ECCE centres. CARE USAID further shows that appropriate policies in the nations can expedite ECD curriculums. Therefore, this study needed to explore the implementation of IEP/WP6 in the ECCE playrooms where children accessed ECD services.

It has already been mentioned that inclusive education policy advocates the inclusion of children with developmental disabilities in full-service schools; however, its successful implementation depends on collaboration with other policies, government departments, and the private sector. Nel et al. [19] identified a gap in human, financial, information, and physical resource constraints in supporting children with disabilities. Disability rights policies advocate for the intradepartmental collaboration of services to address funding, assistive devices, transport, and medical requirements to close the existing gaps and support these children for access to the curriculum.

Most disabled children are deprived of quality teaching and learning due to various factors such as poor socio-economic conditions, lack of appropriate schools or facilities and incompetent teaching staff. In most rural communities, these learners are not recognised as part of a larger community (macrosystem). Bronfenbrenner believes that a close relationship and interaction with the disabled child will influence their outlook on life positively. Therefore, ECCE centres, schools, and teachers/practitioners fulfil an essential secondary role in the young child’s life. This role, however, cannot be replaced by the primary relationship with the parents. The Ecological Systems theory considers the young child’s development in the relationships formed within their environment. Bronfenbrenner’s theory defines the different layers that affect the young child’s development.

The chronosystem applies to the child’s total development, which leads to the individual’s ability to differentiate and know what is wrong and what is right. For example, in personal development, a child needs to be fully developed physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually [14]. In some African cultures, incapacitated children are deprived of their rights and freedom to live with families or participate in certain activities, therefore facing prejudice and discrimination [33].

4. Research Methodology

The researchers applied a qualitative approach to investigate the perceptions of teachers and centre managers in implementing IEP/WP6 in ECCE playrooms. This approach is situated within the interpretivist paradigm. Maree [34] broadly describes qualitative research as any kind of research that produces findings not arrived at using statistical procedures or other means of quantification. A descriptive case study was utilised to explore the implementation of IEP/WP6 in the playrooms/centres in the Eastern Cape Province using interviews and observations. Convenience purposive sampling methods were used as the three centres chosen were inclusive ECD centres situated close to one of the researchers’ workplace [35]. Six participants, three teachers (T1; T2; T3) and three centre managers (CM1; CM2; CM3) were included in this study. Pseudonyms were used for teachers and centre managers to ensure the anonymity of the participants. The authors collected data using individual face-to-face interviews with teachers and centre managers and classroom observations. These individual interviews were employed as the prime data collection technique in exploring the implementation of the IEP/WP6 in ECCE playrooms. This method of data collection was relevant for finding out about the hidden challenges faced by teachers in the ECCE playrooms. Interviews were conducted in both Xhosa and English, depending on the preference of the teachers. The interview schedule consisted of five questions based on the three research questions that the article attempted to answer. The researchers used a voice recorder to record the participants’ responses when conducting interviews (15 questions altogether) and transcribed them later. These were conducted after working hours for approximately 45 min with each group. The participants in this study were all Black females between the ages of 35 and 55 years. All participants were qualified with either a certificate or diploma in ECD. All the teachers had more than five years of teaching experience, and centre managers had more than twelve years of management experience. Semi-structured, open-ended questions used in the interviews were triangulated with an observation schedule. Observations of playrooms also added to the richness of the data. The data analysis process followed a thematic approach in which the codes emanating from the interpretation of the interview and observation were first clustered into categories before being assigned to the different themes that formed the discussion of findings. The researchers compared multiple data sources in search of common themes [36]. The ethical consideration of this study included obtaining informed consent from the Department of Education and the university, maintaining anonymity, confidentiality, privacy, and avoidance of betrayal and deception to meet the requirements of the ethical code of conduct.

5. Findings and Discussion

The authors identified three main themes after detailed data analysis. These themes were:

- Centre managers’ and teachers’ knowledge, understanding, and implementation of inclusive education policy;

- Factors that limited the implementation of the IEP/WP6 in ECCE playrooms/centres; and

- Lack of leadership in the effective implementation of the IEP/WP6 in ECCE playrooms/centres.

A detailed discussion and verbatim quotes from the participants are presented below.

5.1. Theme 1 Knowledge, Understanding, and Implementation of IEP/WP6

Both centre managers and teachers should have sound knowledge and understanding of inclusive education, according to the Department of Education [2]. These centre managers and teachers should know and understand the principles, basic tenets, and how to implement the policy. Although the government has made some advances in ensuring that children with disabilities have their rights recognised, the application of these rights was not prevalent in classrooms [37].

The first interview question sought information on the participants’ knowledge, understanding and implementation of IEP/WP6. The findings revealed a lack of knowledge, understanding, and implementation of IEP/WP6 by all participants. Implementation of the policy starts with participants having profound knowledge and understanding of the policy imperatives, aims, principles, rationale, and impact on providing quality education to children in ECCE playrooms/centres. Centre Manager 1 (CM1) stated that:

We know of White Paper 6 when we heard of it in 2003 in the RNCS (Revised National Curriculum Statement) workshops. We talked about special needs children and that they must be accommodated in our schools and centres. We must not discriminate, make sure that they get access to care, and they must be treated fairly. Regarding the aims, we know a little bit, but the principles, we must admit that we have to go back and read the policy.(CM1)

CM2 also showed a lack of confidence in implementing the policy:

Our understanding of the policy is the information that we got from the trainers. They told us that it is about special needs learners and that we must teach these learners in our schools and centres. We worked in small groups to discuss the implications of the policy at our centres. We knew that since we are from poor rural areas, all the things the policy is asking will be difficult for us.(CM2)

CM 3 thought that by accommodating all children in her schools, she is ultimately implementing the policy: “We accommodate all children. I think we are implementing the policy in that way. I am sure there are other things in the policy that we are not doing correctly”.

From the voices of both the centre managers and teachers, it is evident that some teachers and centre managers had limited knowledge and understanding of the principles of inclusive education and its implementation. However, they knew words pertinent to inclusive education such as ‘equal rights’, ‘rights to equal education’, ‘no discrimination’, ‘treated fairly’, and ‘irrespective of who the child is, the child must be loved and cared for’.

In response to their knowledge, understanding and implementation of IEP/WP6, Teacher 1 (T1) said:

We have heard of White Paper 6 in our discussion with the centre manager. She informed us that this policy is about helping children with disabilities. She told us that every child has equal rights and that we must not discriminate. We agree that every child must be given a chance to education, no matter what their disabilities are. We do not know the full content of the policy and what it exactly says.(T1)

Regarding the understanding of the policy, we must admit that it is challenging for us to read and understand the policy language. We saw this policy only one when our manager showed us at the meeting. We don’t have copies of this policy.(T2)

Our centre manager is telling us we must implement the policy, but we do not know what we must do. We do what we believe in our hearts; we have to care for these special needs children. We must show them love and care and try as much as possible to teach them the necessary skills.(T3)

Participants lacked appropriate knowledge, understanding, and implementation of the policy, which posed a challenge towards implementation efforts. The authors observed that IEP/WP6 had different meanings for different individuals. This misunderstanding of inclusive education is not predominantly South African; it is evident in other countries worldwide [38]. According to Landsberg et al. [6], there is no agreed consensus regarding the understanding and implementation of the inclusive education policy. According to Nind et al. [18], some teachers regard inclusive education as being about learners with disabilities and special needs. Jaeger and Bowman (2005) state that teachers only see inclusion as helping learners who are struggling academically [27]. IEP/WP6 is a policy aimed at guaranteeing equivalent schooling for all young children regardless of race, age, gender, colour, and capability [39].

During the playroom observations, the authors noted that teachers supported children and were often helping them be comfortable in their cots or playpens. Teachers were loving, caring, and compassionate to the little children. The teachers’ attitudes resonate with Bronfenbrenner’s theory, whereby teachers act in loco parentis in the microsystem. According to Bronfenbrenner [31], the microsystem is the first and closest level, where the child forms a positive relationship with the caregiver (teachers).

5.2. Theme 2: Factors Limiting the Implementation of the Policy

According to Walton [40], specific requirements need to be fulfilled for the policy to be implemented. In the three centres visited, there is a clear indication that the policy was not effectively implemented. Participants were not afraid to voice their opinions about the challenges they experienced in implementing the policy. In their responses, both groups of participants shared similar factors that affected the implementation. CM 2 said:

Our biggest challenge in implementing the policy is that we had no training. Furthermore, as teachers, we do not have a copy of the policy document in our files. We want training on the policy, what this policy expects from us as teachers, what we have to do to implement in our playrooms. We don’t get support from the Department on how we should implement the policy.(CM2)

Financial constraint was a significant issue brought up by both groups.

To implement any policy, money is needed. In our rural schools, we do not have the funds or facilities.(T1)

Look at our classrooms; we don’t have carpets, mattresses, cots for our babies, blankets, toys, jungle-gym, crayon, paper, etc. We cannot afford these but have to rely on the goodwill of our poor parents.(T2)

The Department says that because we are not registered with Social Development, we do not qualify for the subsidy.(CM2)

Regarding a conducive learning environment, both teachers and centre managers articulated:

In rural areas, we don’t have a proper playroom for our children. The condition is terrible, broken windows, no ceiling, no toys, nothing to stimulate them (T3). Even our playground is not a safe place. Most of the time, we have to keep our children indoors. This is not adequate stimulation for them (T2). We need money to make sure our school environment is conducive to learning.(CM3)

Another issue raised by both teachers and centre managers was the lack of appropriate resources. They indicated that they have to rely on parents to help with resources. Parents send the wooden toys that they make at home. Teachers were vocal in saying that babies and young children need soft toys to hug and cuddle to feel safe and secure, different textured materials for their sensory development, and resources to stimulate the fine and large gross motor skills.

5.3. Theme 3: The Role of the Department of Education in the Effective Implementation of the IEP/WP6 in ECCE Playrooms/Centres

In South Africa, there has just been a function shift regarding the role of ECD centres from the Department of Social Development (DSD) to the Department of Education (DBE). Regarding the role of the DBE and DSD, Centre Managers 1 and 3 stated:

We need support from the Departments, but they ignore us most of the time. It is challenging to get the department official to come and visit us. We want support in training us on Inclusive Education (CM1). We would like the subject advisor to give us some training on how to implement the policy, share insights about the policy, and share what other centres are doing so that we can learn from this.(CM3)

Participants stated that ECCE centres lack the necessary conducive environment to implement the inclusive education policy. The importance of knowing and understanding IEP/WP6 cannot be overemphasised. IEP/WP6 is considered a strategy to eliminate educational obstacles for young children with disabilities or developmental disabilities to participate in school activities [2].

There seemed to be a lack of efficient training from departmental officials. CM1 expresses her discontentment with the Department of Education. She said, “they call us for meetings with people who know more about the policy to tell us. However, we do not get full training about IEP/WP6 then I cannot implement all that the department wants”.

CM 3 called for more meetings with the departmental official and stated:

If we know and meet with the Department at least once a month, they can show us what we must do with the policy, and then we can come back to our school and implement. It is our responsibility to make sure our children are getting the best.(CM3)

CM2 wanted to be supported with resources for effective implementation of the policy and said:

We know that we must do something for inclusive education, but we don’t have the resources to help us. It is nice to know about all the policies, but we must get help from the department too. At least they should give us good resources such as furniture, carpets, blankets, toys, proper toilets, and facilities for our children.(CM2)

Support is a key to bring about change in curriculum for effective implementation. According to Storbeck and Moodley [4], help in the early years of a baby’s life reinforces all upcoming growth in the areas of socio-emotional, linguistic, and cognitive dominions. Specialists agree that learning begins at birth; thus, the need to lay a solid foundation in the development and growth of young children is essential and should embrace all children, including those with disabilities [5]. The policymakers, in this instance, the Department of Education, need to realise the urgency of training and appropriate resources for the implementation of the policy. This proved to be a main challenge in the ensuring that the IEP was implemented successfully.

The significance of the study is that it highlights the importance of the middle layer, the exosystem, in Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory. This middle layer is the most important cog in the wheel as it could lead to the development of the child, or it could lead to the child’s neglect if it is not functional. The exosystem is the heart of the ecological systems theory. Therefore, it has become urgent to create implementable policies for proper training, monitoring, and support from officials from the Department of Educations and the various levels and structures, especially teachers in ECCE centres. ECCE is the crucial area for early intervention and ECCE policies should be accompanied with practical action plans for the knowledge, roles, and responsibilities of all stakeholders in education. Implementation of the IEP in ECCE centres would be supported by the district officials; resources would be provided for children in need and ECCE teachers would be able to eradicate the challenges mentioned.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

In conclusion, it was clear that centre managers and teachers agreed that the inclusive education policy must be appropriately implemented in all playrooms and centres. However, the challenges are too significant for them to manage the implementation without support. It has become more urgent for the education departments to accept their responsibilities for the ECD sector and provide the necessary leadership, support, and management required for quality ECD. Government departments need to ensure that all children, irrespective of caste and creed, should be given an equal education to become competent and capable citizens in South Africa.

Emanating from the findings, the authors recommend that for the successful implementation of IEP/WP6, the Eastern Cape Department of Education must ensure that all centre managers and teachers are trained on IEP/WP6 on an ongoing basis. A one-off workshop or training is insufficient for policy knowledge, understanding, interpretation, and implementation. More focused training should be planned for ECCE teachers and centre managers. Every teacher should be given a copy of the policy, and perhaps a step-by-step action plan to implement the policy. Resources or finances to purchase the necessary resources could assist in teachers implementing the policy.

It is also recommended that all ECCE centres, especially in rural communities, be supported and managed by the DBE and DSD. This would ensure that they are working according to policy guidelines to provide quality care and support for all young children. Once registered with the DBE and DSD, they will also be eligible for funding and resource provision (infrastructure and human resources). Parents should be encouraged to play a role in their children’s care and support. Workshops and training should be provided for parents to understand their essential part in early childhood education and support for the institution.

For any policy or curriculum to be successful in its implementation, appropriate resources must be made available. Both the parent community and the relevant departments must ensure that the necessary age-appropriate resources for children from birth to four years are made available. These resources should include ramps for children on wheelchairs and crutches, teacher-aids to support teachers in their classes to manage children with disabilities, and ensuring that the teacher-learner ratio is manageable so that all children can receive a quality education. The lessons we have learnt from the non-implementation of the IEP is that the middle layer of the Bronfenbrenner’s framework, as illustrated in Figure 2, which consists of the leadership roles of the different levels from the Department of Education, is crucial for the outer layers and inner layers to function efficiently. The limitation of this study is that it is qualitative and based on a small case study in one province in South Africa, and hence cannot be generalised. Future research regarding the strengthening of the training of district officials regarding their roles and responsibilities in supporting and monitoring ECD centres has become urgent. Perhaps a quantitative study regarding the qualifications, expertise and understanding of the job descriptions of all district officials in all provinces in South Africa would prove useful in developing a functional exosystem for quality inclusive education.

Author Contributions

K.B. supervised, conceptualised, wrote, reviewed and edited the article; J.T. collected data, R.V. wrote and edited the initial draft of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by DHET/EU, grant named TEECCE project (Teacher Education for Early Childhood Care and Education).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of Department of Basic Education, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Pretoria (protocol code EC 19/10/03 and 20 November 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found at www.up.ac.za (accessed on 17 July 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Douglas, S.N.; Meadan, H.; Kammes, R. Early Interventionists’ Caregiver Coaching: A Mixed Methods Approach Exploring Experiences and Practices. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2019, 40, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education (DoE). Education White Paper 6: Special Needs Education—Building an Inclusive Education and Training System. 2001. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/special-needs-education-education-white-paper-6 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Donohue, D.; Bornman, J. The challenges of realising inclusive education in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2014, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storbeck, C.; Moodley, S. ECD Policies in South Africa—What about children with disabilities? J. Afr. Stud. 2011, 3, 28327DA9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Declaration on Education for all and Framework for Action to meet Basic Learning Needs. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001275/127583e.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Landsberg, E.; Krüger, D.; Swart, S. Addressing Barriers to Learning: A South African Perspective, 2nd ed.; Van Schaik Publishers: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of South Africa (RSA). Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996—Chapter 2: Bill of Rights. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/constitution/chapter-2-bill-rights#29 (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Zollers, N.J.; Ramanathan, A.K.; Yu, M. The relationship between school culture and inclusion: How an inclusive culture supports inclusive education. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 1999, 12, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. Using research to encourage the development of inclusive practices. In Making Special Education Inclusive; David Fulton Publishers: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bornman, J.; Rose, J. Believe That All Can Achieve: Increasing Classroom Participation in Learners with Special Support Needs; Van Schaik: Pretoria, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bipath, K.; Aina, A.Y. Early Childhood Development (ECD) centre leadership during COVID-19 in urban and rural areas in South Africa. Altern. Spec. Ed. 2021, 28, 1–11, in print. [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman, R.A.; Nomdo, C. IDASA-Budget Information Service. Available online: https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/cis/omalley/OMalleyWeb/dat/provinccial%20education%20depts%20not%20up%20to%20the%20job.pdf2007 (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Hannaway, D.; Steyn, M.; Hartell, C. The influence of ecosystemic factors on black student teachers’ perceptions and experiences of early childhood education. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2012, 283, 86–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastable, S.B.; Dart, M.A. Developmental stages of the learner. In Nurse as Educator: Principles of Teaching and Learning Practice, 3rd ed.; Bastable, S.B., Dart, M.A., Eds.; Jones & Bartlett Publishers: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 147–198. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht, P.; Nel, M.; Nel, N.; Tlale, D. Enacting understanding of inclusion in complex classroom practices of South African teachers. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2015, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, H.B. Tracing historical shifts in early care and education in South Africa. J. Educ. 2010, 48, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, E.; Ruszynak, L. Choices in the design of inclusive education courses for pre-service teachers: The case of a South African University. Intl. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2016, 64, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nind, M.; Flewitt, R.; Payler, J. Social constructions of young children in ‘special’, ‘inclusive’ and home environments. Child. Soc. 2011, 25, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, N.; Müller, H.; Rheeders, E. Support services within inclusive education in Gauteng: The necessity and efficiency of support. Mevlana Int. J. Educ. 2011, 1, 38–53. [Google Scholar]

- Swart, E.; Pettipher, R. A framework for understanding inclusion. In Addressing Barriers to Learning: A South African Perspective; Landsberg, E., Ed.; Van Schaik: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Basic Education (DBE). Draft Guidelines on Severely Intellectual Difficulties: Life Skills. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Legislation/Call%20for%20Comments/Draft%20SPID%20Learning%20Programme.pdf?ver=2016-11-07-133329-850 (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Lambert, C.; Jomeen, J.; McSherry, W. Reflexivity: A review of the literature in the context of midwifery research. Br. J. Midwifery 2010, 18, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, L.; Katz, J. Oh, Canada: Bridges and barriers to inclusion in Canadian schools. Support Learn. 2015, 30, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugweni, R.M.; Dakwa, F.E. Exploring the implementation of education for all in Early Childhood Development in Zimbabwe: Successes and challenges. Int. J. Case Stud. 2013, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlo, F.D. Experiences of Learning Support Teachers in the Foundation Phase with Reference to the Implementation of Inclusive Education in Gauteng. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, J. Not My Responsibility: The Impact of Separate Special Education Systems on Educators’ Attitudes toward Inclusion. Educ. Policy Anal. Strateg. Res. 2018, 13, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, P.T.; Bowman, C.A. Understanding Disability: Inclusion, Access, Diversity, and Civil Rights; Praeger: Westport, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Basic Education (DBE). Report on the Implementation of Education White Paper 6 on Inclusive Education. Available online: https://static.pmg.org.za/160308overview.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Yssel, N.; Engelbrecht, P.; Oswald, M.M.; Eloff, I.; Swart, E. Views of inclusion: A comparative study of parents’ perceptions in South Africa and the United States. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2007, 28, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Department of Basic Education (DBE). Policy on Screening, Identification, Assessment. Available online: https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ressources/south_africa_strategy_screening_support_sias-2014.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. (First Published in 1979). [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, V. Early child development: A conceptual model. In Early Childhood Council Annual Conference; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2010; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M.; Ghazinour, M.; Hammarström, A. Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: What is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Soc. Theory Health 2018, 16, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maree, K. Completing Your Thesis and Dissertation: A Practical Guide; Van Schaik Publishers: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed and Mixed Methods Approach, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano, C.V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag, S. Connection between a successful inclusive education programs for students with severe disabilities. University of Oxford. New York City. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2014, 12, 157–174. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/tqse20/curren (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Polat, F. Inclusion in education: A step towards social justice. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2011, 31, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetler, S.; Baltzer, K. The climate of inclusive classrooms: The pupil perspective. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2011, 9, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, E. Getting inclusion right in South Africa. Intervention in school and clinic. Hammill Instit. Disabil. 2011, 46, 240–245. Available online: http://www.sagepublications.com (accessed on 17 July 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).