Assessment of the Application of Content and Language Integrated Learning in a Multilingual Classroom

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

- the groups consist of students of different nationalities,

- teaching takes place in English (not native for students and the teacher),

- the curriculum includes the discipline “Spanish”, which is studied in English, and is suitable for the use of content and language integrated learning and a multilingual approach. The point was to learn Spanish. English was the teaching language, as the students came from different linguistic backgrounds – their L1s were different, teaching was on their L2s, and they were learning an L3.

1.2. Literature Review

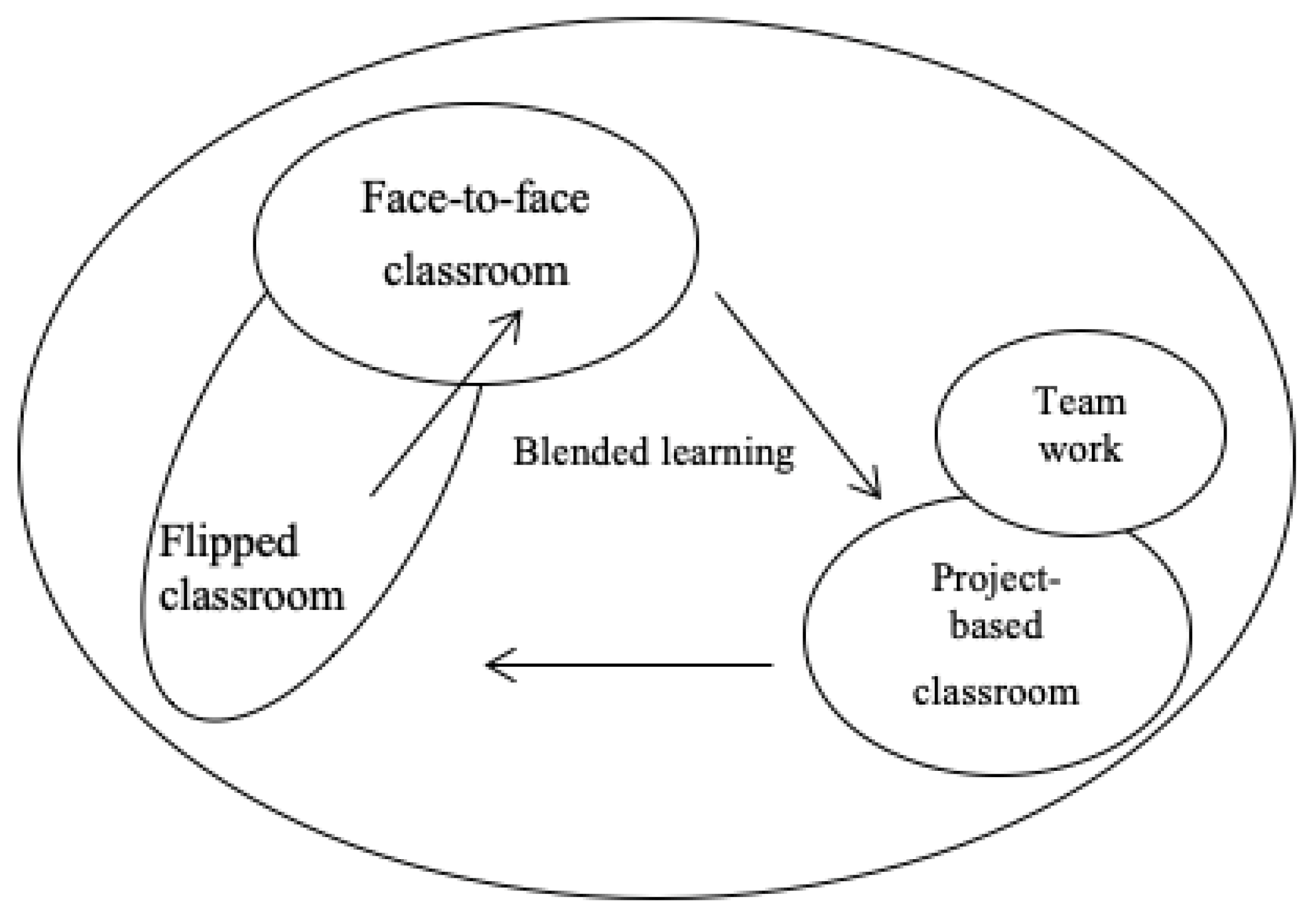

1.2.1. Content and Language Integrated Learning and Its Forms

1.2.2. Multilingualism

2. Materials and Methods

- Is there a significant difference in the level of Spanish proficiency before and after the course?

- Does the proposed educational model help to improve knowledge in the discipline of “International Business”?

- Is the proposed learning model effective from the students’ perspective?

3. Results

3.1. Learning Results

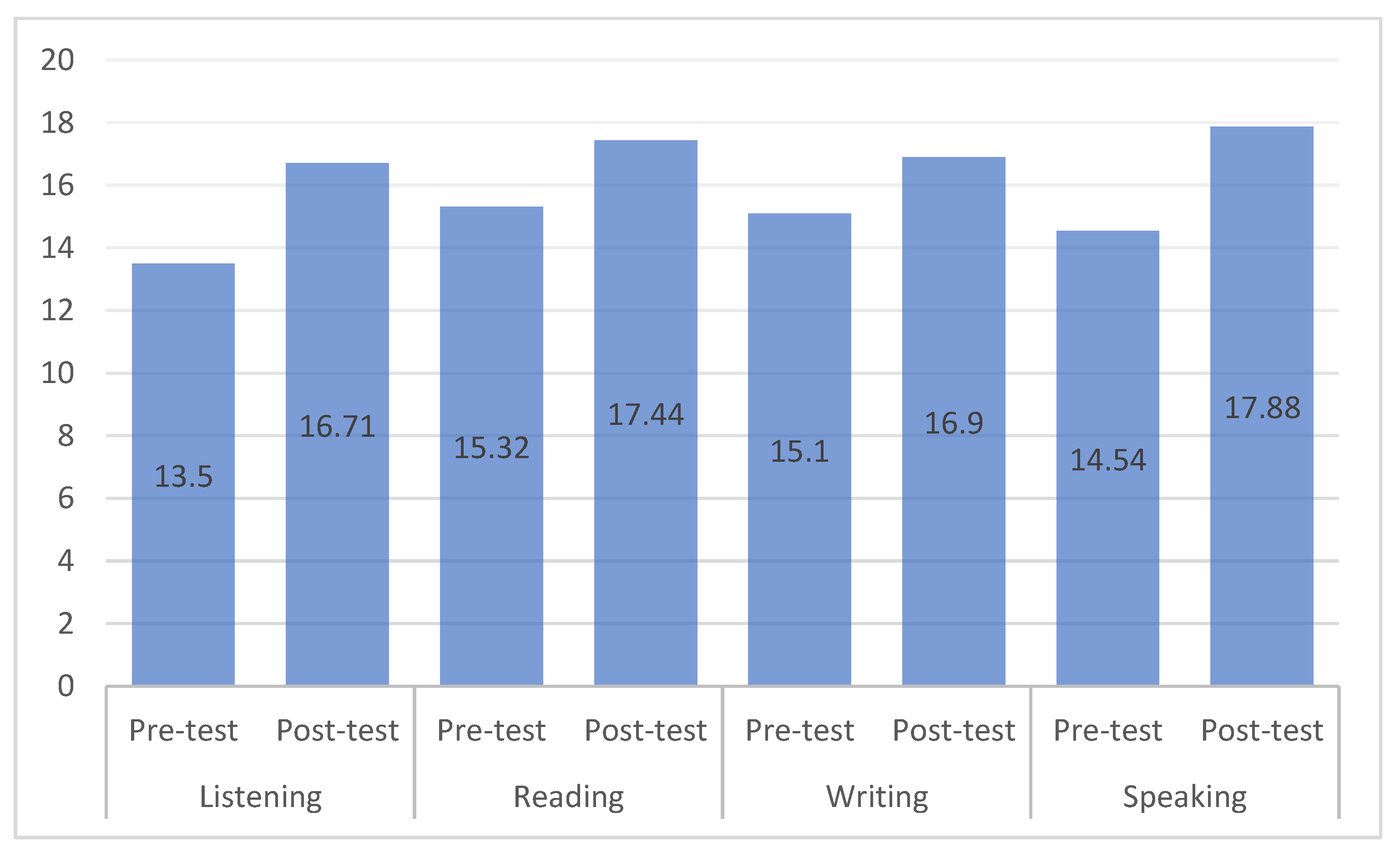

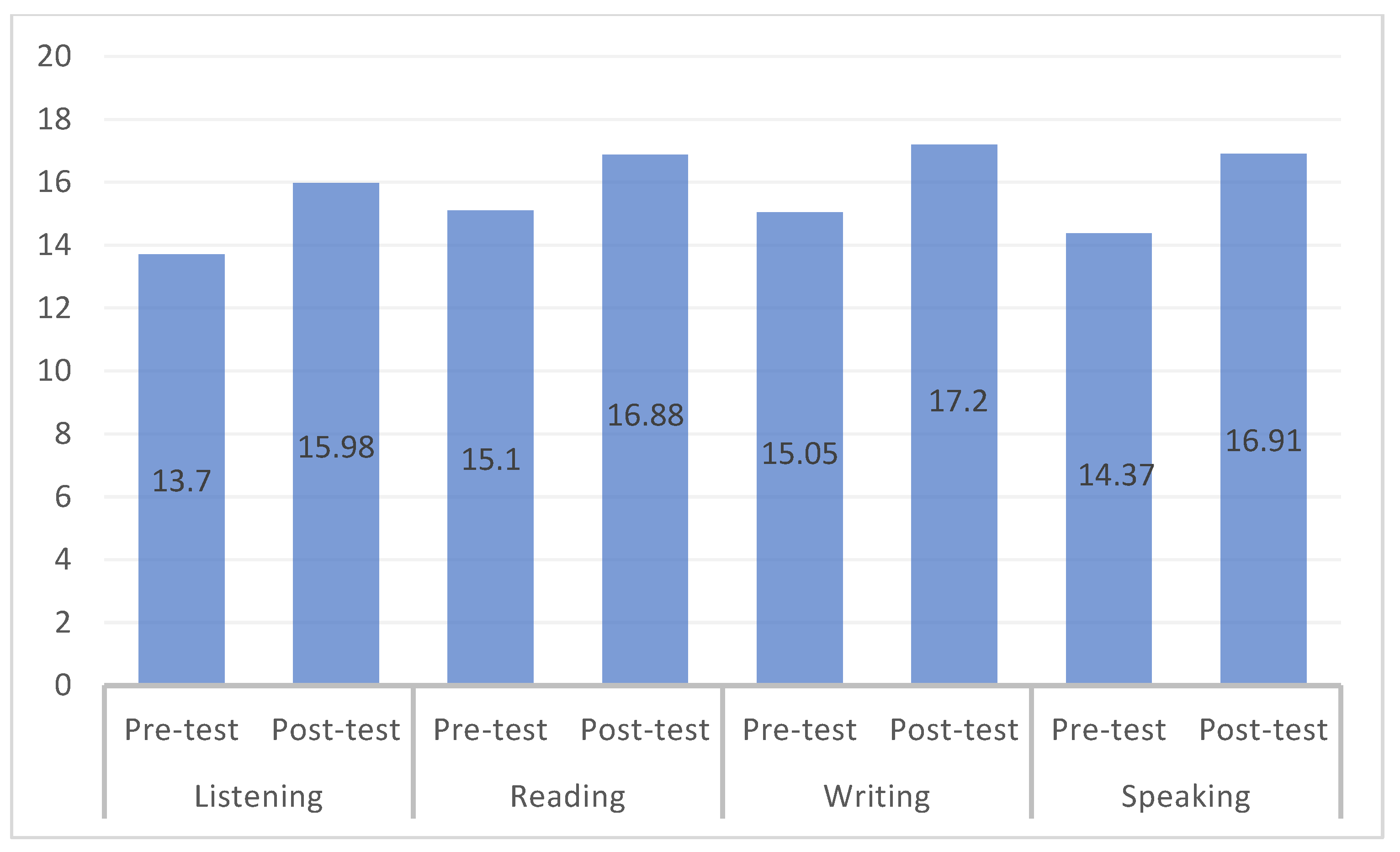

3.1.1. Spanish Testing

3.1.2. Professional Discipline Testing

3.1.3. Efficiency of the Learning Model from Students’ Perspective

- Two students with high scores on the results of two tests (professional discipline and Spanish),

- Two students with a high score in Spanish and a low score in professional discipline,

- Two students with high scores in professional discipline and a low score in Spanish,

- Two students with low scores on two tests (professional discipline and Spanish).

- Give a brief assessment of the course passed;

- Highlight the advantages of learning according to the proposed model;

- Highlight the shortcomings of training according to the proposed model;

- Do you consider it expedient to introduce the discipline “international business” into Spanish classes?

- Do you find the use of several languages in the learning process useful?

- An unusual shape: over the past 2 years of studying the discipline “Spanish”, students have become accustomed to the traditional form.

- For the successful completion of the discipline, professional knowledge is required, which not all students have in the same amount.

- Working in a new format requires a good knowledge of the Spanish language. Students experienced difficulty using the Spanish language.

- Interesting form of presentation of material, including various forms of activity and work (“working with case studies was the most interesting part, classes became much more interesting”);

- Open recognition of the importance of using the mother tongue on an equal footing with English for learning a second foreign language (“reliance on the native language greatly simplified the study L3”);

- Study of professional vocabulary in Spanish (“we were able to learn really useful Spanish”);

- Obtaining skills in the use of Spanish in business communication (“it was useful to learn how to apply Spanish in future professional activities and negotiations”);

- Significant progress in the development of speaking skills (“this semester a lot of attention was paid to the spoken aspect, which is usually very lacking”);

- Increasing motivation to learn due to the lack of monotony in the educational process (“tasks were interesting, which motivated to complete them all”).

- Unnecessary complexity (“too difficult, no one knows why”);

- Insufficient knowledge of Spanish to implement such training (“we do not have such a level of Spanish to master professional content”);

- Insufficient attention is paid to developing writing skills and explaining grammar (“it was better to do more grammar, not business”);

- Overloaded educational process, work on cases in a group takes more time (“such a program requires a lot of time, which we do not have, since we study other disciplines”).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baranova, T.; Kobicheva, A.; Tokareva, E. Web-based environment in the integrated learning model for CLIL-learners: Examination of students’ and teacher’s satisfaction. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Antipova, T., Rocha, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1114, pp. 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Baranova, T.A.; Tokareva, E.Y.; Kobicheva, A.M.; Olkhovik, N.G. Effects of an integrated learning approach on students’ outcomes in St. Petersburg Polytechnic University. In Proceedings of the 2019 the 3rd International Conference on Digital Technology in Education, Yamanashi, Japan, 25–27 October 2019; pp. 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodarskaya, E.B.; Grishina, A.S.; Pechinskaya, L.I. Virtual learning environment in lexical skills development for active vocabulary expansion in non-language students who learn English. In Proceedings of the 2019 12th International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering (DeSE), Kazan, Russia, 7–10 October 2019; pp. 388–392. [Google Scholar]

- Admiraal, W.; Westhoff, G.; De Bot, K. Evaluation of bilingual secondary education in the Netherlands: Students’ language proficiency in English. Educ. Res. Eval. 2006, 12, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranova, T.; Khalyapina, L.; Kobicheva, A.; Tokareva, E. Evaluation of students’ engagement in integrated learning model in a blended environment. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baranova, T.; Kobicheva, A.; Tokareva, E.; Vorontsova, E. Application of translinguism in teaching foreign languages to students (specialty “Ecology”). E3S Web Conf. 2021, 244, 11034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D.; Hood, P.; Marsh, D. CLIL. Content and Language Integrated Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlberger, S.; Wegner, C. Bilingualer Sachfachunterricht in Deutschland und Europa-Darstellung des Forschungsstands (Bilingual content learning in Germany and Europe–outline of the state of research). Herausford. Lehr.* Innenbildung-Z. Zur Konzept. Gestalt. Und Diskuss. 2018, 1, 45–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D. Content and language integrated learning: Towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2007, 10, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) at School in Europe; Eurydice: Brüssel, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas, M. Analysing a whole CLIL school: Students’ attitudes, motivation, and receptive vocabulary outcomes. Lat. Am. J. Content Lang. Integr. Learn. 2016, 9, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belyaeva, I.G.; Samorodova, E.A.; Voron, O.V.; Zakirova, E.S. Analysis of innovative methods’ effectiveness in teaching foreign languages for special purposes used for the formation of future specialists’ professional competencies. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Canga Alonso, A.; Arribas Garcia, M. The benefits of CLIL instruction in Spanish students’ productive vocabulary knowledge. In Encuentro: Revista de Investigación e Innovación en la Clase de Idiomas; Universidad de Alcalá de Henares: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Volume 24, pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dallinger, S.; Jonkmann, K.; Hollm, J.; Fiege, C. The effect of content and language integrated learning on students’ English and history competences–Killing two birds with one stone? Learn. Instr. 2016, 41, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, N.K. Extramural exposure and language attainment: The examination of input-related variables in CLIL Programmes. Porta Ling. Rev. Interuniv. Didáctica Leng. Extranj. 2018, 29, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudo, J.D.D.M. The impact of CLIL on English language competence in a monolingual context: A longitudinal perspective. Lang. Learn. J. 2019, 48, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo, M.N. Are CLIL students more motivated? An analysis of affective factors and their relation to language attainment. Porta Ling. Rev. Interuniv. Didáctica Leng. Extranj. 2018, 29, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallinger, S.; Jonkmann, K.; Hollm, J. Selectivity of content and language integrated learning programmes in German secondary schools. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2016, 21, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Bünder, W. Bilingualer Unterricht in den Naturwissenschaften (Bilingual classes in science). Math. Und Nat. Unterr. 2008, 61, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Haagen-Schützenhöfer, C.; Mathelitsch, L.; Hopf, M. Fremdsprachiger Physikunterricht: Fremdsprachlicher Mehrwert auf Kosten fachlicher Leistungen? (Learning physics in a foreign language: Added value at cost of subject achievements?). Z. Didakt. Nat. 2011, 17, 223–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lamsfuß-Schenk, S. Fremdverstehen im Bilingualen Geschichtsunterricht: Eine Fallstudie (Foreign Understanding in Bilingual History Classes: A Case-Study); Peter Lang: Frankfurt, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Madrid, D. Monolingual and bilingual students’ competence in social sciences. In Studies in Bilingual Education; Madrid, D., Hughes, S., Eds.; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Surmont, J.; Struys, E.; Noort, M.V.D.; Van De Craen, P. The effects of CLIL on mathematical content learning: A longitudinal study. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2016, 6, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anghel, B.; Cabrales, A.; Carro, J.M. Evaluating a bilingual education program in Spain: The impact beyond foreign language learning. Econ. Inq. 2016, 54, 1202–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Sanjurjo, J.; Fernández-Costales, A.; Blanco, J.M.A. Analysing students’ content-learning in science in CLIL vs. non-CLIL programmes: Empirical evidence from Spain. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2019, 22, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondring, B.; Ewig, M. Aspekte der Leistungsmessung im bilingualen Biologieunterricht (Aspects of performance assessment in bilingual biology classes). IDB-Ber. Des. Inst. Didakt. Biol. 2005, 14, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, D.; Barrios, E. A comparison of students’ educational achievement across programmes and school types with and without CLIL Provision. Porta Ling. 2018, 29, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piesche, N.; Jonkmann, K.; Fiege, C.; Keßler, J.-U. CLIL for all? A randomised controlled field experiment with sixth-grade students on the effects of content and language integrated science learning. Learn. Instr. 2016, 44, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canz, T.; Piesche, N.; Dallinger, S.; Jonkmann, K. Test-language effects in bilingual education: Evidence from CLIL classes in Germany. Learn. Instr. 2021, 75, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallinger, S.; Jonkmann, K.; Hollm, J.; Fiege, C. Merkmale erfolgreichen bilingualen Sachfachunterrichts. Die Rolle der Sprachen im deutsch-englischen Geschichtsunterricht (Aspects of successful bilingual subject education. The role of languages in German-English history lessons). In Die Wirksamkeit Bilingualen Sachfachunterrichts: Selektionseffekte, Leistungsentwicklung und die Rolle der Sprachen im Deutsch-Englischen Geschichtsunterricht; Dallinger, S., Ed.; Ludwigsburg University of Education: Ludwigsburg, Germany, 2015; pp. 145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdi, G.; Py, B. To be or not to be a plurilingual speaker. Int. J. Multiling. 2009, 6, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirss, L.; Säälik, Ü.; Leijen, Ä.; Pedaste, M. School effectiveness in multilingual education: A review of success factors. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafato, R. The non-native speaker teacher as proficient multilingual: A critical review of research from 2009–2018. Lingua 2019, 227, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafato, R. Teachers’ reported implementation of multilingual teaching practices in foreign language classrooms in Norway and Russia. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 105, 103401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O.; Sylvan, C.E. Pedagogies and practices in multilingual classrooms: Singularities in pluralities. Mod. Lang. J. 2011, 95, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.; Cook, G. Own-language use in language teaching and learning. Lang. Teach. 2012, 45, 271–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heuzeroth, J.; Budke, A. The Effects of multilinguality on the development of causal speech acts in the geography classroom. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotti, M.; Kroon, S. Multilingual classrooms at times of superdiversity. In Discourse and Education. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 3rd ed.; Wortham, S., Kim, D., May, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liwiński, J. The wage premium from foreign language skills. Empirica 2019, 46, 691–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Etxebarrieta, G.R.; Pérez-Izaguirre, E.; Langarika-Rocafort, A. Teaching minority languages in multiethnic and multilingual environments: Teachers’ perceptions of students’ attitudes toward the teaching of basque in compulsory education. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raud, N.; Orehhova, O. Training teachers for multilingual primary schools in Europe: Key components of teacher education curricula. Int. J. Multiling. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Viegen, S.; Zappa-Hollman, S. Plurilingual pedagogies at the post-secondary level: Possibilities for intentional engagement with students’ diverse linguistic repertoires. Lang. Cult. Curric. 2020, 33, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. Monolingual versus multilingual foreign language teaching: French and Arabic at beginning levels. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krulatz, A.; Iversen, J. Building inclusive language classroom spaces through multilingual writing practices for newly-arrived students in Norway. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 64, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y. Teachers’ identities as ‘non-native’ speakers: Do they matter in English as a lingua franca interactions? In Criticality, Teacher Identity, and (In) Equity in English Language Teaching. Educational Linguistics; Yazan, B., Rudolph, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 35, pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; Ponte, E. Legitimating multilingual teacher identities in the mainstream classroom. Mod. Lang. J. 2017, 101, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.; Asli, A. Bilingual teachers’ language strategies: The case of an Arabic–Hebrew kindergarten in Israel. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 38, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, B.; Tastanbek, S. Making the shift from a codeswitching to a translanguaging lens in english language teacher education. TESOL Q. 2021, 55, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstens, A. Translanguaging as a vehicle for L2 acquisition and L1 development: Students’ perceptions. Lang. Matters 2016, 47, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haukås, Å. Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism and a multilingual pedagogical approach. Int. J. Multiling. 2015, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russia, M. Curriculum for Grades 10 and 11 According to Federal Government Education Standards (FGOS); The Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation: Moscow, Russia, 2018.

- PIRAO. Modernization Project for the Contents and Technologies of Teaching the Subject “Foreign Languages”; Russian Academy of Education: Moscow, Russia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Burner, T.; Carlsen, C. Teacher qualifications, perceptions and practices concerning multilingualism at a school for newly arrived students in Norway. Int. J. Multiling. 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, J.Y. Pre-service teachers’ translanguaging during field placement in multilingual, mainstream classrooms in Norway. Lang. Educ. 2019, 34, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J.; Genesee, F. Psycholinguistic perspectives on multilingualism and multilingual education. In Beyond Bilingualism, Multilingualism and Multilingual Education; Cenoz, J., Genesee, F., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 1998; pp. 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dana Di, P. CLIL in the Business English Classroom: From Language Learning to the Development of Professional Communication and Metacognitive Skills. 2015. Available online: https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/blog.nus.edu.sg/dist/7/112/files/2015/04/CLIL-in-the-Business-English-Classroom_editforpdf-2da6nlw.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Nikula, T.; Dafouz, E.; Moore, P.; Smit, U. Conceptualising Integration in CLIL and Multilingual Education; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Results | Sort of Data Collection | Type of Data |

|---|---|---|

| Spanish proficiency | Scores on testing (N = 47) | quantitative |

| Professional discipline knowledge | Scores on testing (N = 47) | quantitative |

| Efficiency of the learning model from students’ perspective | Interview (N = 24) | qualitative |

| Survey (N = 8) | quantitative |

| Group | Category | Test | Mean (SD) | t-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Listening | Pre-test | 13.5 (1.87) | 5.3 *** |

| Post-test | 16.71 (1.94) | |||

| Reading | Pre-test | 15.32 (2.1) | 4.1 *** | |

| Post-test | 17.44 (1.97) | |||

| Writing | Pre-test | 15.1 (1.79) | 2.2 * | |

| Post-test | 16.9 (1.88) | |||

| Speaking | Pre-test | 14.54 (1.74) | 5.2 *** | |

| Post-test | 17.88 (1.78) | |||

| Control | Listening | Pre-test | 13.7 (1.83) | 4.3 *** |

| Post-test | 15.98 (2.02) | |||

| Reading | Pre-test | 15.1 (1.99) | 2.1 * | |

| Post-test | 16.88 (1.85) | |||

| Writing | Pre-test | 15.05 (1.89) | 4.2 *** | |

| Post-test | 17.2 (1.94) | |||

| Speaking | Pre-test | 14.37 (1.69) | 4.5 *** | |

| Post-test | 16.91 (1.78) |

| Group | Testing Results | Mean | SD | t-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Professional discipline | 71.87 | 5.72 | 1.7 |

| Control | Professional discipline | 73.44 | 6.13 |

| Statement | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| The current learning model can give more advantages rather than disadvantages to my academic achievement | 4.41 | 0.32 |

| The current learning model can enhance my multilingual competency | 3.87 | 0.39 |

| The current learning model provides complete content in my learning with good exercise | 3.95 | 0.28 |

| The current learning model provides me with different learning styles and can make my learning more fun | 4.11 | 0.42 |

| The current learning model helps to make my lesson more effective compare to traditional learning model | 4.34 | 0.33 |

| Average efficiency level | 4.14 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baranova, T.; Mokhorov, D.; Kobicheva, A.; Tokareva, E. Assessment of the Application of Content and Language Integrated Learning in a Multilingual Classroom. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120808

Baranova T, Mokhorov D, Kobicheva A, Tokareva E. Assessment of the Application of Content and Language Integrated Learning in a Multilingual Classroom. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(12):808. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120808

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaranova, Tatiana, Dmitriy Mokhorov, Aleksandra Kobicheva, and Elena Tokareva. 2021. "Assessment of the Application of Content and Language Integrated Learning in a Multilingual Classroom" Education Sciences 11, no. 12: 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120808

APA StyleBaranova, T., Mokhorov, D., Kobicheva, A., & Tokareva, E. (2021). Assessment of the Application of Content and Language Integrated Learning in a Multilingual Classroom. Education Sciences, 11(12), 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120808