Abstract

In increasingly diverse cultural contexts, the intercultural perspective favors an enriching coexistence between cultures, with volunteering being an exercise that allows for a critical transformation of reality in order to achieve a more supportive and equitable society. This article aims to find out how university students conceive of volunteering, as well as their level of participation. The sample was made up of 208 students from the Pedagogy and Social Education degrees of the University of Granada during the 2019/2020 academic year. An ad hoc questionnaire was applied, which incorporated a standardised instrument (Adapted Values Test), as well as questions designed by the authors. The results underline the positive axiological perception of volunteering. The participants understand volunteering as a helping role that depends on the social, personal, and professional motivations of the students. However, this positive perception is not transformed into active participation and continuous links with voluntary organisations. The conclusions indicate that university students value volunteering as a necessary task for the social good, although their participation is low, and it is necessary to transform the pro-social awareness of university students into real participation.

1. Introduction

The current global context, in which technologies and advances allow us to interact with any subject, physically or virtually, has blurred the boundaries between people [1], exponentially multiplying the relational and coexistence processes between different cultures. In this context, the awareness and visibility of cultural difference becomes insufficient in a context in which inequalities must be resolved through action. Linked to this, one of the proposals on which different experts agree [1,2,3] is the need to promote collaboration and participation with third sector entities, whose work deals with aspects that, directly or indirectly, are related to socio-cultural coexistence. Volunteering can favor intercultural interaction, in addition to a more human and realistic vision of cultural diversity. In this sense, several studies have corroborated that volunteering promotes both the understanding of cultural diversity [4] and the development of intercultural competence [5,6]. Based on this premise, we are interested in knowing the perception of volunteering and the degree of participation in this type of activity in future education professionals.

Talking about volunteering means entering into a reality at a global level oriented towards the achievement of a more just and equitable social context for all human beings. In essence, the volunteers are people and groups who help and collaborate together disinterestedly in order to make this world a better place [7]. Such is their importance at a local and supranational level that, in 1986, the United Nations created an International Volunteer Day (5 December) to commemorate the work of volunteers every year. The number of volunteers and organisations worldwide, working together to change the factors and issues affecting their community and the planet, is very large. The 2018 State of the World’s Volunteers report speaks of a figure of one billion formal (within an organization) and informal (without an association or organization) active volunteers [8]. This same report, when considering only formal volunteer staff, estimates its magnitude at 109 million full-time workers. They are therefore an essential resource, and their work on the front line during major crises, disasters, or difficulties is key [9]. As can be seen, this is not just a positive activity for the social sphere, but also a way of being and of being in the world. To volunteer involves the dedication of time, altruistically and freely, to actions whose benefits do not directly affect the individual sphere of the subject, but are carried out to benefit a certain collective [10], i.e., a task that favours the well-being and personal satisfaction of those who experience it [11]. The fact is that volunteering has a positive impact both on psychosocial health [12,13,14,15] and on the axiological development of the individual. Thus, by volunteering, we express [16] and put into practice moral, ethical, and social values [17]; we collaborate to achieve real social justice; and we acquire professional and personal skills.

In the specific case of Spain, volunteering is a consolidated practice which remains stable, and which was adapted to the characteristics of the social, political and economic context. In Spain, the relationship between the university and volunteers was a reality since the reform of the Organic Law on Universities [18], where—in Article 92—it is stipulated that “the universities shall encourage the participation of the members of the university community in activities and projects of international cooperation and solidarity” (p. 16254), which is endorsed by the current State Law on Volunteering [19] and the role given to the university (Article 22). However, the popularity of volunteering in Spanish society did not correspond to the low level of participation and real collaboration in these organisations. Several different studies show this [20,21,22]. The work of Caride, et al. [20], with secondary education students, highlights that only 1.14% of the respondents participate in associations or volunteer on weekends. In the case of Ferreira et al. [21], with a different sample of secondary education students, the percentage of students who did voluntary work at the weekends reached 4.6%. Thus, both studies show that the percentage of Spanish secondary school students who volunteer at weekends is less than 5%.

It is also necessary to consider that the promotion of voluntary activities during adolescence is not as common as it should be, occupying 3.8% of the extracurricular activities offered to seconday education students in Spain [22], such that 81.4% of this population neither worries nor thinks about getting involved in these tasks. In this line, the most current data, provided by the Plataforma de Voluntariado en España (PVE) [23], indicates that 6.2% of the Spanish population over 14 years of age is a volunteer. If we consider the variable of students, the percentage is 5.2%. Within this profile, 45.5% of students are in the first or second cycle of higher education in doctorate studies [24], rising to 53.2% in the study of the PVE [25], such that almost half of the students who volunteer belong to the university student community, reflecting the fact that confidence and participation in volunteering grows with the level of education [26].

Despite the good data, it is necessary to continue working towards an even more socially committed university community of students, and a key to this is the need to strengthen the link between the voluntary sector and the university [27]. In this way, spaces of reflection and action can be created in the university that promote an impulse of voluntary work beyond awareness and social responsibility, favouring—at the same time—the acquisition of skills linked to community service [28]. This could increase the level of participation of this group in the present, during their training stage, and in the future, contributing to the social sense of education.

Objectives

Therefore, the general objective of this study is to ascertain the reality regarding the axiological perception and the participation of university students in the field of volunteering. This purpose is segmented into several specific objectives:

- (a)

- To examine the hierarchy of values of university students and the importance of the terms of the social category linked to volunteering. This will allow us to find out the importance and level of satisfaction that university students give to values related to volunteering.

- (b)

- To determine the level of confidence in volunteering, the type of linkage, and the frequency of participation. In this way, we will see what the real involvement and participation of university students in volunteer work is.

- (c)

- To verify whether there are significant differences linked to gender and degree variables with respect to the perception of volunteering. This objective allows us to know if factors such as gender or education influence the opinion of university students about the values related to volunteering.

- (d)

- To analyse the concept of volunteering and the factors that influence university students to volunteer. We will look in depth at how they conceive of volunteering and which aspects condition or encourage them to participate in and carry out volunteer work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

We started from a mixed descriptive and interpretative study, based on a non-experimental design. The information was collected from the sample by means of an ad hoc questionnaire, treating the information both in a statistical and interpretative way, in order to ascertain the axiological perception and the volunteerism of the participants, as well as their involvement with and their conception of this phenomenon.

2.2. Sample

The sample was made up of 208 university students from the Faculty of Education of the University of Granada, with an average age of 21.61 years, during the 2019/2020 academic year. The students were selected in a non-probabilistic (intentional) manner among the degrees of Pedagogy and Social Education, facilitating the research team’s access to the students of the subjects of ‘Social History and Culture of Education’ and ‘Democratic and Citizenship Education’ (Degree in Pedagogy), and ‘Organization and Management of Non-Formal Education Institutions’ (Degree in Social Education). It was a convenience sample, the demographic data of which is collected below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample distribution.

2.3. Instruments

The information was collected through an ad hoc questionnaire. It was made up of four sections: (a) sociodemographic data, asking about gender, age and degree; (b) an Adapted Values Test [29], i.e., a standardised instrument that allows the axiological hierarchy of the subjects of study to be known. Based on the integral axiological model of Gervilla [30], the test is composed of 11 categories of values (corporal, intellectual, affective, individual, moral, aesthetic, social, political participation, ecological, instrumental, and religious), which are composed of 25 terms each. The participant must show their perception of liking or disliking the value by means of a Likert-type scale with scores that vary between −2 and 2 points (very unpleasant, unpleasant, indifferent, pleasant, and very pleasant) regarding the 275 terms included in the test. There are two ranges of scores for interpretation: value category scores, made up of 25 words, with a range of scores between −50 and 50 points; and direct term scores, with a score between −2 and 2 points. The quality criteria of the instrument consider the validity of the content, as confirmed by its application in different studies [31], and reliability, reaching a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.754, denoting an acceptable reliability. With the implementation of this questionnaire, we want to ascertain the axiological hierarchy of the participants, since it influences their actions and decision-making. Specifically, we analysed the category of social values. The reason for this is that the category of social values includes terms that are directly related to volunteering (Association, Caritas, Collaborate, Joined Hands, Doctors Without Borders, Volunteering, Red Cross), which allows us to ascertain the axiological opinion of the participants on these aspects. This lead to (c) three closed questions, in which the level of confidence in the voluntary organisations, the type of linkage, and the frequency of participation are questioned. The response alternatives are based on the studies of González-Anleo and López-Ruiz [32], and Benedicto [33]. (d) There were also two open questions (What does it mean for university students to volunteer? What factors influence their participation in these actions?), in which the concept of voluntary work and the factors that must be considered in order to carry it out were put to the participants of this study.

2.4. Process and Data Analysis

First, the students were informed that their participation was voluntary, and that the data would be treated anonymously. The questionnaire was administered to the students using the Google Forms application (online) for flexibility and convenience, both for completion and for the recording of the responses. Depending on the stipulated objectives, quantitative and qualitative analyses were developed. With regard to the quantitative data, SPSS v.25 was used. A descriptive statistics test was carried out for: the Adapted Values Test scores, the volunteer-related vocabulary in the social values category, and the answers to the closed-ended questions about the level of trust, type of attachment and frequency of participation in volunteering. A Mann–Whitney U test was also carried out due to the non-normal distribution of the data (Table A1, gender difference: Levene (p ≤ 0.05) and Kolmogorov–Smirnov (p ≤ 0.05); Table A2, degree difference: Levene (p ≤ 0.05) and Kolmogorov-Smirnov (p ≤ 0.05)). This non-parametric test allowed us to verify the existence of significant differences by gender or degree with respect to the perception of the terms of the category of the social values linked to volunteering. Regarding the qualitative information, a content analysis [34] was implemented. Considering its different phases (pre-analysis, a system for the categorization of the information, codification, interpretation), the results were focused on the interpretation phase, in which the answers from the two open question were interpreted.

3. Results

The results are presented in the order of the proposed objectives, thus allowing a progressive and exhaustive understanding of the information in accordance with the investigations carried out, differentiating the quantitative and qualitative analysis from the information obtained.

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

This subsection presents the main results obtained in relation to the specific objectives [a], [b] and [c].

3.1.1. Specific Objective [a]

We begin with the hierarchy of the values of the students of the Pedagogy and Social Education degrees of the University of Granada who participated in the research (Table 2), using the range of scores per category (−50 to 50 points) in order to obtain the descriptive statistics.

Table 2.

Hierarchy of sample values.

The maximum scores reflect that, in all of the categories except religion (48), at least one participant considered all of the words to be very pleasant. The minima show that no participant considered all of the words in a category to be very unpleasant (−50 points), approaching this only in the case of religious values. The rest only reflects negative scores in the values of political participation (−15) and intellectual participation (−4), with the minima being more positive than the negative. With respect to the averages obtained, the values of a moral nature are the best evaluated (44.91). The moral values are followed by the individual values (43.48), the affective values (42.54), and the ecological values (41.69), all of which are above 40 points. On the other hand, categories such as political (25.44) and instrumental values (26.28) are among the worst considered. The last position is for the category of religious values (−0.58), with a perception of indifference and a negative score. If we go deeper into the dispersion, the category with the greatest homogeneity in the answers was morality (6.49), followed by affective values (6.53). On the opposite side, the religious category obtained the highest variability, with a dispersion that was much higher than the average (21.01). Also noteworthy is the heterogeneity in the assessments of the terms of the political participation category (13.57), which occupied the penultimate hierarchical position.

Taking into account the data obtained in the hierarchy, we placed the focus on the category of social values, in which the vocabulary related to volunteering is found. Bearing in mind the hierarchy of values mentioned above, the social category was placed in the intermediate zone (5th position) of the hierarchy (36.89), with a high homogeneity in the answers of the participants (9.39).

In order to determine the importance that the sample gives to volunteering, we analysed the perception that they have of the values related to this activity that were included in the Adapted Values Test, with it being necessary to use the range of assessment by words (−2 to 2 points). According to the selected terms (Table 3), the action of collaboration is the best considered (1.72) and the one that obtained the least dispersion in the assessments (0.46). This is followed by voluntary work itself and Doctors Without Borders, which is perceived as very pleasant, along with Joined Hands. The rest of the words are considered pleasant, with a low average difference compared to the words assessed as very pleasant. It should be highlighted that Cáritas is the association which obtained the lowest score (1.30), presenting the greatest heterogeneity in the participants’ answers (0.70).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the vocabulary related to volunteering.

3.1.2. Specific Objective [b]

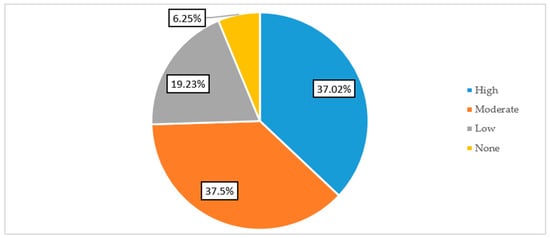

This positive perception is related to the level of trust towards voluntary organizations (Figure 1 and Table 4), in which 155 participants (74.52%) reflected a lot or quite a lot of trust towards them, with only 6.25% of the sample (13 participants) expressing no trust at all.

Figure 1.

Level of trust towards voluntary organizations. Source: Authors’ own work.

Table 4.

Level of trust towards voluntary organizations.

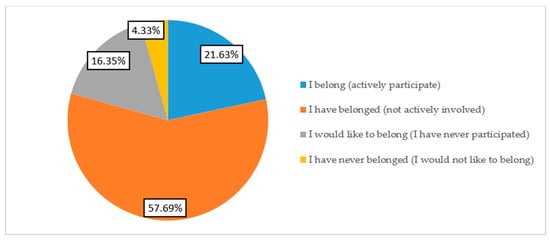

However, only 45 students (21.63%) stated that they belong to and actively participate in a voluntary organisation (see Figure 2 and Table 5). It should be noted that more than half of the respondents (57.69%, 120 participants), although they were not actively involved in voluntary organisations, reported having been a member of one, while 16.35% had never been, but would like to be. The low percentage (4.33%) of students (9 participants) who neither belonged to nor would like to belong to a voluntary organisation should be highlighted.

Figure 2.

Type of link with voluntary organisations. Source: Authors’ own work.

Table 5.

Type of link with voluntary organisations.

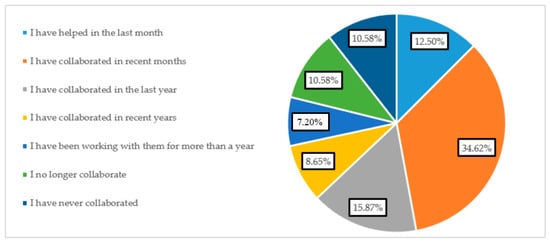

Along this line, Figure 3 and Table 6 show the frequency of participation in voluntary actions. As can be seen, the percentages of those who actively participated in the last month (12.50%, 26 participants), those who no longer collaborate (10.58%, 22 participants), and those who have never done so (10.58%, 22 participants) are quite close. It is worth noting that 105 participants (50.49%) helped in the period of time between the last few months and the last year.

Figure 3.

Frequency of participation in voluntary organisations. Source: Authors’ own work.

Table 6.

Frequency of participation in voluntary organizations.

3.1.3. Specific Objective [c]

In order to analyze whether there are significant differences in the perceptions of volunteering with respect to gender and degree (subjects studied), we again took the seven terms for the social category and their rank (−14 and 14 points). With respect to the gender variable, the Mann–Whitney U test shows that there are no significant differences (p ≥ 0.05) in the consideration of volunteering. On the other hand, the degree variable does show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) when the Mann-Whitney U-test is applied, as is reflected in Table 7.

Table 7.

Difference in the perception of volunteering depending on the degree.

The results underline that the students in the social education degree have a better appreciation of the voluntary field (actions and organisations) than those in the pedagogy degree.

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

Specific Objective [d]

The qualitative analysis was structured around two open-ended question: (1) What does it mean for university students to volunteer? (2) What factors influence their participation in these actions?

Regarding the meaning of being a volunteer (first question), most of the answers were built around the action of helping, underlining this concept as a maxim of the volunteer, as the evidence shows. In this way, help was the common element in the answers of the participants:

“I define it as collaborating to improve the human and social conditions of young people.”(S. 201)

“It is that you want to help as much as you can, with nothing in return, because you do it from the heart.”(S. 114)

Moreover, based on the answers of the participants, it was important to associate the meaning of volunteerism with a form of identity expression. Volunteering helps us to respond to the question of who we are through the act of giving without expecting to receive anything in return. This is a commitment that is defined by the vocation, and the implementation of moral, ethical, and social values [35]. This was reflected in the answers, in which the participants associated it with commitment and disinterested dedication to others. In both sets of evidence, it was emphasized that the volunteer didn’t receive financial compensation:

“To be a volunteer is to be able to show what you really are, since by volunteering you do not receive financial compensation.”(S. 37)

“To contribute to improving the lives of people who need it most by vocation, without the aim being financial compensation.”(S. 62)

As for the factors that influence volunteering, motivation was the main reason. However, the answers to the second question made it possible to differentiate between whether the motivation was of a social, personal or professional nature. Motivation of a social nature was related to the purpose of achieving a better society, linking the role of the volunteer with the benefit he or she brings to the recipients of his or her work [36]. This idea was reflected in the following evidence, in which the volunteer was happy to help other people:

“I am motivated by the knowledge that I am giving a part of myself to other people.”(S. 180)

In the personal dimension, there was an interest in the growth of the identity of the people who do voluntary work. In this way, the answers reflected that volunteering was a practice that helped both those who received and those who gave it, transforming them as persons and favouring their psychosocial well-being [37]. This was evidenced in the following response from a participant:

“Trying to help others, without any form of obligation but on your own, thus making what you do fulfill you as a person.”(S. 11)

It was also necessary to point out the motivation of volunteering with respect to the professional sphere. The students saw, in volunteering, an opportunity to apply the knowledge acquired during their training stage, and a possible opportunity to access the labour market. Volunteering thus became an opportunity to gain experience, as the following evidence shows:

“Being a volunteer means an opportunity to put into practice the knowledge acquired and to be able to gain experience in a more dynamic way.”(S. 117)

4. Discussion

This study has shown that university students have a positive perception of volunteering, which does not always translate into active participation in such actions. We are faced with a reality that is considered relevant because it is oriented towards helping and collaborating with others, but which does not translate into a majority participation on a social level in this cooperation. Thanks to the questionnaire completed by the students, we have obtained information about several aspects concerning their values, and we have learned about the axiological importance given to volunteering by students of education at the University of Granada. We also know what their level of trust, participation, and involvement in voluntary associations is. Finally, we are able to know their personal conception about the concept of volunteering and the aspects that influence them to do it.

The examination of the axiological hierarchy of the students (specific objective [a]) allows us to know their priorities with respect to the world of values. In this sense, despite the favourable consideration of social values, which include those linked to voluntary work, these occupy an intermediate position. The fact that the moral category occupies the first position underlines the importance given to values that give ethical and practical meaning to the rules of living together. However, the second position of individuals, which includes all that concerns the personal and identity component of the subject, reiterates that young people prioritise their own well-being over that of society, thus superimposing the liberation of autonomy on community morality. The first places in the hierarchy, as well as the intermediate position of social values, coincide with the studies of Álvarez and Rodríguez [38].

We continue with specific objetive [b]. Regarding the level of trust in the voluntary organisations, 155 participants (74.52%) show a lot or quite a lot of trust in them (Figure 1 and Table 4), a finding that is similar to that registered by the Plataforma de Voluntariado in Spain [23], where this evaluation was shared by 79% of the young people, and to that reported by González-Anleo [26], in which this level of confidence was shared by 65.7% of the young people. The active participation encompasses 21.63% of the sample, obtaining somewhat lower percentages (28%) than those of López-Ruiz [39], and being higher than the data of the study by Benedicto [33], in which only 9% of those surveyed belonged actively to a volunteer organization. However, our work reflects the fact that, among young people who do not volunteer, the percentage of those who want to participate is four times higher than those who do not want to join in. This differs from the data provided by the Plataforma del Voluntariado en España (PVE) [23], in which the percentages of those who would like to participate (55.1%) and those who do not want to belong (40.3%) are more similar. Based on these data, we have to take into account that 8 out of 10 Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) consider the level of involvement and commitment of university students with respect to volunteer actions to be positive [40]. Despite this, our sample under study reflects less active participation and less interest in volunteering. If we look at the frequency of collaboration, only 12.5% of the participants had collaborated in the last month, while 34.62% had done so in recent months. This figure is lower than the usual activity of the voluntary organisations, with the frequency of participation, according to the PVE [25], being mainly once a week. However, it is important to highlight, from a positive point of view, that only 21.16% of the students surveyed had never collaborated or no longer collaborate, a figure which rises to 91.10% in Benedict’s research [33], reflecting the greater commitment of the sample to volunteering, although not frequently.

In terms of the presence of significant differences (specific objective [c]), the gender variable did not show differences in the perceptions of volunteering. This fact reflects that, at the level of reasoning or assessment, both sexes attach a similar importance to volunteering, a situation that does not translate into practice, in which the profile of volunteering is mostly female (83%), as shown by the results of the VII study on university volunteering [40], a reality that is supported by other studies which also highlight that women are more active in pro-social issues than men [41]. For the degree variable, the perceptions of the social educators are more positive than those of the pedagogues. This position is linked to the social and personal characteristics that define such students, in which empathy, vocational components, and resilience are key elements [42]. This fact coincides with the study by Wong et al. [43], which highlights the ways in which the participation in voluntary actions and/or activities increases in those subjects who show a greater capacity for resilience.

The analysis of the volunteering of students (specific objective [d]) suggests that it is conceived of as a way of being, and of being in the world, the axis of which is the disinterested action of helping to improve social reality. Within being a free and altruistic activity, motivation is the main factor to carry out this work, as the participants of this study have stated. In this sense, it is necessary to distinguish between social, personal, and professional motivation. Social motivation was oriented towards service, help, and collaboration with society, this being one of the main reasons given by university students to become volunteers, coinciding with the data from the Plataforma de Voluntariado en España [23], in which 64% of the respondents placed help as the main reason for volunteering. On the other hand, personal motivation is based on the process of identity (re)construction, in which volunteer tasks bring psychosocial well-being to those who carry them out from a moral and ethical perspective, coinciding with the theses of different studies [12,15,44]. As for professional motivation, statements were collected that underline the link between volunteering and the acquisition of professional experience, thus denoting a perception of volunteering among young people as an opportunity to access the labour market, an issue which was already considered in Benedict’s study [33].

We are, therefore, faced with a reality that is present in the axiological hierarchy of young people, which manifests itself mainly at the level of awareness, without this leading to an increase in their commitment to activism. Young people value and highlight the importance and need for volunteering, but the vast majority do not participate actively. We are thus faced with a phenomenon that is defended through reasoning, but not always through actions. Volunteering is a commitment to others and to personal development. However, there are other motivations, such as the possibility of accessing the world of work or acquiring professional skills.

One limitation is the sample of students, with an interesting increase in the number of participants, as well as the possibility of the consideration of other degrees and other universities, in order to obtain a broader view of the reality of volunteering in the university sphere. Future lines of research include the design and implementation of a university volunteering proposal that takes into consideration the students’ motivations (social, personal, and professional), as well as the type of participation and frequency that is most in line with their wishes, in order to provide them with prosocial experiences that are adapted to their interests, and that allow them to experience the psychosocial benefits of participating in such volunteering work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.-A. and E.C.-M.; methodology, E.G.-G.; software, E.C.-M.; formal analysis, E.S.-R.; investigation, A.C.-A. and E.G.-G.; resources, E.G.-G.; data curation, E.S.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.-R.; writing—review and editing, A.C.-A. and E.G.-G.; supervision, E.C.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results of the parametric assumptions for the variable of sex.

Table A1.

Results of the parametric assumptions for the variable of sex.

| Topic | Sex | Levene | Kolmogorov-Smirnov | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Significance | Statistic | Significance | ||

| Volunteer | Women | 5.650 | 0.018 * | 0.209 | 0.000 * |

| Men | 0.198 | 0.003 * | |||

Source: Own elaboration. * = p < 0.05.

Table A2.

Results of the parametric assumptions for the variable of the university degree.

Table A2.

Results of the parametric assumptions for the variable of the university degree.

| Topic | University Degree | Levene | Kolmogorov-Smirnov | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Significance | Statistic | Significance | ||

| Volunteer | Pedagogy | 87.897 | 0.000 * | 0.155 | 0.000 * |

| Social education | 0.210 | 0.000 * | |||

Source: Own elaboration. * = p < 0.05.

References

- De Vicente, D.P.; Olivencia, J.J.L.; Terrón, A.M. Perceptions about cultural diversity and intercultural communication of future teachers. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. de Form. del Profr. 2019, 23, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalva-Vélez, A.; Olivencia, J.J.L. La interculturalidad en el contexto universitario: Necesidades en la formación inicial de los futuros profesionales de la educación. Educar 2019, 55, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo-Canosa, V.; Ortiz-Jiménez, L.; Sánchez Romero, C.; Berlanga, M.C.L. Teacher Training in Intercultural Education: Teacher Perceptions. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caki, F. European Voluntary Service and Intercultural Competence in Understanding Islamic Culture. Sosyol. Derg. 2012, 24, 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Vveinhardt, J.; Bendaraviciene, R.; Vinickyte, I. Mediating factor of emotional intelligence in intercultural competence and work productivity of volunteers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, G.N.; Vargas, A.P. Voluntariado, complemento en la formación integral del modelo intercultural. Caso: Licenciatura en Comunicación Intercultural. Rev. Estud. En Educ. 2018, 1, 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, A. Prólogo. Creación de nuevos modelos de resiliencia con las comunidades. In Informe sobre el estado del voluntariado en el mundo 2018. El lazo que nos une: Voluntariado y resiliencia comunitaria; Programa de Voluntarios de las Naciones Unidas, Ed.; Organización de las Naciones Unidas: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Programa de Voluntarios de las Naciones Unidas. Informe sobre el estado del voluntariado en el mundo 2018. El lazo que nos une: Voluntariado y resiliencia comunitaria; Programa de Voluntarios de las Naciones Unidas, Ed.; Organización de las Naciones Unidas: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–144. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, O. Prefacio. Visibilización de los lazos invisibles. In Informe Sobre el Estado del Voluntariado en el mundo 2018. El lazo que nos une: Voluntariado y resiliencia Comunitaria; Programa de Voluntarios de las Naciones Unidas, Ed.; Organización de las Naciones Unidas: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Roszkowski, M.J.; Kinzler, R.J.; Kane, J. Profile of a Residential Learning Community Dedicated to Service-Learning on Schwartz’s Typology of Values. J. Serv. Learn. High. Educ. 2014, 3, 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, S.; Stutzer, A. Is volunteering rewarding in itself? Economica 2007, 75, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, Y.Y.; Chui, W.H.; Wong, L.P. Need satisfaction mechanism linking volunteer motivation and life satisfaction: A mediation study of volunteers subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 114, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ferraro, K.F. Volunteering and depression in later life: Social benefit or selection processes? J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piliavin, J.A.; Siegl, E. Health benefits of volunteering in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2007, 48, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecina, M.L.; Chacón, F. ¿Es el engagement diferente de la satisfacción y del compromiso organizacional? Relaciones con la intención de permanencia, el bienestar psicológico y la salud física percibida en voluntarios. An. de Psicol. 2013, 29, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, F.; Pérez, T.; Flores, J.; Vecina, M.L. Motivos del Voluntariado: Categorización de las Motivaciones de los Voluntarios Mediante Pregunta Abierta. Interv. Psicosoc. Rev. Sobre Igual. y Calid. de Vida 2010, 19, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deusdad, B. El respeto a la identidad como una forma de inclusión social: Interculturalidad y voluntariado social. Educ. Siglo XXI 2013, 31, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- De España, G. Ley Orgánica 4/2007, de 12 de abril, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 6/2001, de 21 de diciembre, de Universidades. Boletín Oficial del Estado 2007, 89, 16241–16260. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2007/04/12/4/dof/spa/pdf (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Jefatura del Estado. Ley 45/2015, de 14 de octubre, de Voluntariado. Boletín Oficial del Estado 2015, 247, 1–20. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2015/BOE-A-2015-11072-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2020).

- Antonio Caride Gómez, J.; Lorenzo Castineiras, J.J.; Rodríguez Fernandez, M.A. Educar cotidianamente: El tiempo como escenario pedagógico y social en la adolescencia escolarizada. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2012, 20, 19–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Delgado, J.P.; Pose Porto, H.; De Valenzuela Bandín, Á.L. El ocio cotidiano de los estudiantes de Educación secundaria en España. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2015, 25, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.C.; Iglesias, L.; Vargas, G.; Rouco, J.F. Usos e imágenes del tiempo en el alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO): Entre la escuela, la familia y la comunidad/ Uses and images of the time in the Spanish compulsory secondary education. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2012, 20, 61–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plataforma del Voluntariado de España. La acción voluntaria en 2018; Plataforma del Voluntariado de España: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio del Voluntariado. Perfil de la solidaridad en España. Retrato del voluntariado 2019; Plataforma del Voluntariado de España: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Plataforma del Voluntariado de España. Así somos en 2018. Retrato del voluntariado en España; Plataforma del Voluntariado de España: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- González-Anleo Sánchez, J.M.; López-Ruiz, J.A. Valores morales, finales y confianza en las instituciones: Un desgaste que se acelera. In Jóvenes Españoles ENTRE dos siglos 1984–2017; Fundación SM: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 13–52. [Google Scholar]

- Maran, D.A.; Soro, G.; Biancetti, A.; Zanotta, T. Serving others and gaining experience: A study of university students participation in service learning. High. Educ. Q. 2009, 63, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, J. La formación de las competencias profesionales a través del aprendizaje servicio. Cult. Educ. 2013, 25, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervilla, E.; Casares, P.; Entrena, S.; González, G.; Jiménez, F.J.; Lara, T.; Santos, M.; Soriano, A. Test de Valores Adaptado (TVA_adaptado), 2018. Registro de la Propiedad Intelectual. No. 04/2017/1538 (11 April 2017). Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/11/8/415/htm (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Gervilla, E. Un modelo axiológico de educación integral. Rev. Española de Pedagogía 2000, 215, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cívico Ariza, A.; González Garcia, E.; Colomo Magana, E. Análisis de la percepción de valores relacionados con las TIC en adolescentes. Rev. Espac. 2019, 40, 18. Available online: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a19v40n32/19403218.html (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- González-Anleo Sánchez, J.M.; López-Ruiz, J.A. Jóvenes Españoles Entre dos Siglos 1984–2017; Fundación SM: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 1–313. [Google Scholar]

- Benedicto, J.; Echaves, A.; Jurado, T.; Ramos, M.; Tejerina, B. Informe Juventud en España 2016; Instituto de la Juventud: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 1–684. [Google Scholar]

- Colomo, E.; Gabarda, V. ¿Qué Tipo de Docentes Tutorizan las Prácticas de los Futuros Maestros de Primaria? REICE. Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. y Cambio en Educ. 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnanz, E. Voluntariado y participación. Rev. Española del Terc. Sect. 2011, 18, 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiber, D.A.; Martin, F.B.; Amigo, J.C. La educación para el ocio como preparación para la jubilación en Estados Unidos y España. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2012, 20, 137–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.L.V.; Fuertes, F.C.; Abad, M.J.S. Satisfacción en el voluntariado: Estructura interna y relación con la permanencia en organizaciones. Psicothema 2009, 21, 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.Á.; Sabiote, C.R. El valor de la institución familiar en los jóvenes universitarios de la Universidad de Granada. Bordón 2008, 60, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.A.L. Cultura y ocio Juveniles: Jóvenes Espectadores y Actores en la Diversidad cultural. In Jóvenes españoles Entre dos Siglos 1984–2017; González-Anleo, J.M., Ruiz, J.A.L., Eds.; Fundación SM: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 165–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Mutua Madrileña. VII Estudio sobre Voluntariado Universitario; Fundación Mutua Madrileña: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Inglés, C.; Benavides, G.; Redondo, J.; García-Fernádez, J.; Ruiz Esteban, C.; Estévez, C. Conducta Prosocial y rendimiento académico en estudiantes españoles de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Anales de Psicología 2008, 25, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, L.P. Deontología y código deontológico del educador social. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2012, 19, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wong, P.K.S.; Fong, K.W.; Lam, T.L. Enhancing the Resilience of Parents of Adults With Intellectual Disabilities through Volunteering: An Exploratory Study. J. Policy Pr. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 12, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciá, E.S.; Martínez, R.L.; Román, M.J.S. Promoción y formación del voluntariado con personas mayores en la universidad española. Int. J. Develop. Educ. Psychol. Revista INFAD de Psicología. 2018, 2, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).