The Enhancement of Creative Collaboration through Human Mediation

Abstract

1. Introduction

In a society undergoing constant change in which developing and applying new technologies are the driving force of evolution, creativity emerges as a fundamental “tool” for contemporary individuals [2] (p. 132).

The essence of artistic practice would then reside in the invention of relationships between subjects; each work of art would embody the proposal to inhabit a common environment and the work of each artist, a fabric of relationships with the world that in turn would generate other relationships, and so on to infinity [7] (p. 7).

It is also crucial to acknowledge that activities promoting internal and external experiences provide a greater range of knowledge in lifelong learning processes; life itself is the main learning event.

Here lies the fundamental responsibility of educators in the school environment: the development of students through mediation, in which language is a privileged instrument [27] (p. 20).

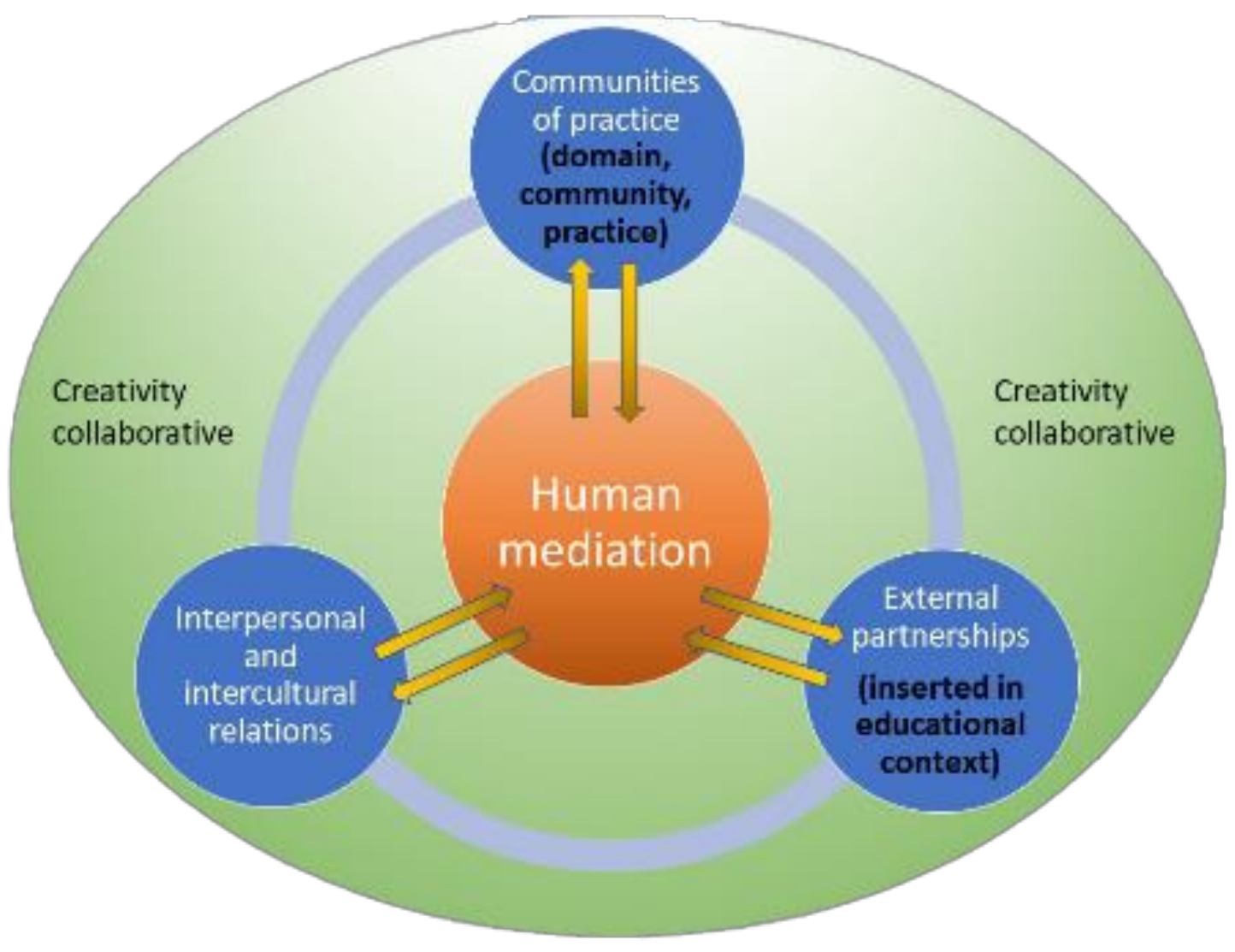

Creativity is nurtured by the diversity of cultural experiences we acquire by participating in our groups and communities. At the same time, it is made possible by culture and enables its growth and transformation, diversifying the range of possible experiences for you and others. This is a vision of distributed creativity, a creativity that brings together people and context, people and material objects, and recognizes their participation and co-evolution in creative activity [30] (p. 56).

Presentation of the “I Am Who I Am” Project Theme

- -

- What contributions and interlinkages stand out among the participants as influential elements in collaborative creativity throughout the process?

- -

- What are the mediations that are evident among students in the elaboration of artistic production throughout the process?

- -

- To what extent do values such as freedom and flexibility in classroom management influence creative collaboration practices?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Tool and Procedure

- (1)

- In the learning processes, do you feel that the activities, guided and accompanied by the teachers, followed a flexible or rigid pedagogical methodology? Yes or no? Explain.

- (2)

- Are the teachers’ guidelines motivating and encouraging for students to experiment and learn?

- (3)

- Do you think that teachers’ guidance, throughout the learning process, has contributed to the evolution of your creative skills? Yes? No? In what ways?

- (4)

- Do you consider constant contact with your colleagues to be an asset?

- (5)

- During the development of your work, can you mention any aspect in which you have felt collaboration, mutual help from your colleagues?

- (6)

- What skills have you acquired during the course of this work? Social, personal, transversal and specific expertise?

- (7)

- What changes can you observe in your colleagues after this work has been carried out?

- (8)

- For you, what differences were there between the exercise Project 1—“I am who I am” and the work carried out in the context of Training in Working Context (FCT)? Identify the most obvious ones.

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Importance of Interpersonal and Personal Relationships in Communities of Practice

3.1.1. Social Relations in the Class (Teacher–Student and Pupil–Student)

There is also this emotional concern. [The teacher said:] “Look, if you are not well today, do not go to the workshop and stay in the part of the project. [It is] really important so that you can also do a good job, right? There is no [...] authority [saying you have to] do it! Do it!”(AM004, 2019, 00:26:45, interview 2)

A personal difference that I found was also during Work Context Training. I already knew the teachers. I already knew the people. This allowed me to have more confidence regarding what I wanted to do, more security, and not to doubt so much my choices.(AD008, 2019, 00:31:36, interview 2)

Colleague X also had a very complex job [...], and sometimes, [when] I was waiting for something in my work, I would help her, so it was also good to learn to work with the materials she used.(AL003, 2019, 00:31:58, interview 1)

I asked X what he thought about how I was doing the arm: “Is it all right? Is it bad?” X told me what he thought [...], and I think it makes us rich. X did the same thing, and it makes us rich.(AC005, 2019, 00:20:00, interview 2)

All the help [...], all the concern we all had [...], we were in the middle of the workshop and...: “Look, have you been able to do that yet?” [...] “Have you been able to recover that?” [...] Since we were all doing this process of [...] accompanying each other, so it is also funny to see our object grow and objects of others.(AM004, 2019, 00:42:54, interview 2)

3.1.2. Elaboration of Artistic Production and Self-Knowledge

I took this question of the primordial and began to develop it with several references [...] to the Triadic Ballet and the Butoh art and another reference to constructivism. All these references are part of a construction, and the idea of construction is that it is primordial in my work. This is always present. I am supposed to play with this question of the primordial that is not seen, and the references I sought were purposely so that what I consider my individuality would not be visible. They are beliefs related to the limitation and the way the form manages to be perpetuated and limited in a certain artistic work. [...] I couldn’t remain indifferent to all the small steps that I took with everything provided, so I tried to play with it.(AM02, 2019, 00:01:09, interview 2)

Organicity and poetics are present in the idea of construction, which I consider myself to be. In this project, I end up falling into the contradiction of trying to define who I am. In sculpture, its elements define me, neither visually nor by their symbolism: they only relate to the need to limit myself to a form.(portfolio, AM002, 2019)

3.2. Educational Strategies and Classroom Management

Freedom and Flexibility in Creative, Collaborative Practices

Freedom in terms of, for example, telling us that you really have these solutions, you can choose which one you want.... This is also a very important thing considering that [...] it is a creative process [...] and, this is so inherent to each one.(AL003, 2019, 00:28:00, interview 1)

I was thinking of making all the flowers the same. [...] Then, I was offered ways of making the flowers that were not as I had imagined and not making all the shapes the same, and the work became much more interesting.(AL003, 2019, 00:30:39, interview 1)

We want to do one thing and come up with ways and different ways of doing that thing. Maybe I already think differently from last year [...]; maybe I can already cover other different ways of doing and using new materials.(AC005, 2019, 00:24:15, interview 2)

My colleagues [...] were central to how we all develop a different way of thinking, the crossing of these thoughts, and also does critical thinking.(AM004, 2019, 00:31:17, interview 1)

and identifies its learning asFacing not only [...] the image I have of the works of others but I also know what is behind them and all the explanation of [something] that exists and [...] all the help that was also given to me in the constructive process and all this sharing of knowledge, not only in the face of the works but also in the face of the people we are and [...] in the sharing of space with which we also come into contact, with each person’s behavior towards the things that happen. Therefore, it is a learning experience in terms of opinions and access to new theories and everything else but as a behavioral thing of knowing how to act, knowing how to be.(AM004, 2019, 00:32:34, interview 1)

An adaptation in all aspects [...] all the situations that arise for us [...], not only the behavioral ones, the interactions that we have with people but also the constructive ones, but in the end, it was that adaptation in all aspects and knowing how to extend me a little to it. In other words [...], this thing of stagnating, there is some comfort in it, knowing that no matter how this situation arises, we are, we continue to be, but we will extend ourselves a little more. [...] I think that is what I learned.(AM004, 2019, 00:37:45, interview 2)

We are all [...] with different sobriety about things. [...] I think we have all grown a lot. [...] the way we even talk about things is really [...] different and [...] doing all this time perspective: well, we were at this point, and now we are doing this. [...] It is rewarding [...] because I feel that not only have I grown, but we have all grown together.(AM004, 2019, 00:41:51, interview 2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Importance of Interpersonal and Personal Relationships in Communities of Practice

4.1.1. Social Relations in the Class (Teacher–Student and Pupil–Student)

4.1.2. Elaboration of Artistic Production and Self-Knowledge

A work done by the artist [...] is in the interconnection, game, and participation with the spectator. The artistic creation takes place, not in the artist’s mind acting under an inspiring muse, nor in the eyes of the public, impacted by a particularly special work, but in the encounter between the two, in the relationship, in the duration of the game that gives existence to work [7] (pp. 5–6).

4.2. Educational Strategies and Classroom Management

Freedom and Flexibility in Creative, Collaborative Practices

To educate means, then, to enable, to empower, so that the learner can seek the answer to what he or she asks, means to form for autonomy [...]. His method: dialogue. It is the disciple who must discover the truth. Therefore, education is self-education [44] (p. 10).

Transdisciplinarity maximizes learning by working with images and concepts that mobilize together the mental, emotional, and bodily dimensions, weaving both horizontal and vertical relationships of knowledge. It creates situations of greater involvement of students in the construction of meaning for themselves [46] (p. 76).

It is known that the phenomenon [creativity] is complex, multifaceted, and multidetermined. Its expression results from a complex network of interactions between individual factors and variables in the socio-historical-cultural context that interferes with creative production, with an impact on creative expressions, on the opportunities offered for the development of creative talent, and also on the modalities of creative expression, recognized and valued [4] (p. 48).

People reflect the communities and societies that they integrate, so, as Bandura states, “people are in part the products of their environments, but in selecting, creating, and transforming their environmental circumstances, they are also producers of environments” [33] (pp. 75–76).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lambert, P.A. Understanding Creativity. In Creative Dimensions of Teaching and Learning in the 21st Century; Cummings, J.B., Blatherwick, M.L., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 12, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Valquaresma, A.; Coimbra, J.L. Criatividade e Educação: A educação artística como o caminho do futuro? Educ. Soc. Cult. 2013, 40, 131–146. Available online: https://www.fpce.up.pt/ciie/sites/default/files/ESC40_A_Valquaresma_J_Coimbra.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2018).

- Klimenko, O. La Creatividad como un desafio para la educacíon del siglo XXI. Educación y Educadores. Educ. Educ. 2008, 11, 191–210. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/eded/v11n2/v11n2a12.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2019).

- Alencar, E.M.L.S. Criatividade no Contexto Educacional: Três Décadas de Pesquisa. Psicol. Teor. e Pesqui. 2007, 23, 45–49. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/ptp/v23nspe/07.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Alencar, E.M.L.S.; Fleith, D.S. Escala de práticas docentes para a criatividade na educação superior. Avaliação Psicológica 2010, 9, 13–24. Available online: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/pdf/avp/v9n1/v9n1a03.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Eça, T. A educação artística e as prioridades educativas do início do século XXI. Rev. Ibero Am. Educ. 2010, 52, 127–146. Available online: http://www.rieoei.org/rie52a07.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2018).

- Rodriguèz, J.R. Creatividad en el Arte: Descentramientos, ampliaciones, conexiones, complejidad. Encuentros Multidiscip. 2008, 10, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Agirre, I. Teorías y Práctices de la Educación Artística, 1st ed.; Octaedro/EUB: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; pp. 141–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lubart, T. Psicologia da Criatividade; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alencar, E.S.; Fleith, D.S.; Borges, C.N.; Boruchovitch, E. Criatividade em Sala de Aula: Fatores Inibidores e Facilitadores Segundo Coordenadores Pedagógicos. Psico-USF 2018, 23, 555–566. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712018230313 (accessed on 2 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Bahia, S.; Nogueira, S.I. Entre a teoria e a prática da criatividade. In Psicologia da Educação: Temas de Desenvolvimento, Aprendizagem e Ensino; Miranda, G.L., Bahia, S., Eds.; Relógio d’Água: Lisbon, Portugal, 2005; Volume 5, pp. 332–363. Available online: https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/2721/1/entre-a-teoria-e-a-pr%c3%a1tica.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2018).

- Bruner, J. O Processo da Educação; Edições 70: Lisbon, Portugal, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. Available online: https://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/07-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Delors, J. Educação: Um Tesouro a Descobrir. Relatório para a UNESCO da Comissão Internacional sobre Educação para o Século XXI, 1998. Porto: Asa. Available online: http://dhnet.org.br/dados/relatorios/a_pdf/r_unesco_educ_tesouro_descobrir.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Wertsch, J.V.; Tulviste, P.L.S. Vygotsky and contemporary developmental psychology. Dev. Psychol. 1992, 28, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, D. School art education: Mourning the past and opening a future. JADE 2006, 25, 26–27. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2006.00465.x (accessed on 15 October 2017). [CrossRef]

- Branco, A.U. Values, Education and Human Development: The Major Role of Social Interactions’ Quality Within Classroom. In Alterity, Values, and Socialization, Cultural Psychology of Education 6; Branco, A.U., Lopes-de-Oliveira, M.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 6, pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M. A educação artística no trilho de uma nova cidadania. Rev. de Estud. Investig. Psicol. Educ. 2017, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, L. Understanding individual patterns of learning: Implications for the well-being of students. Eur. J. Educ. 2008, 43, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Educação como Prática da Liberdade; Paz e Terra: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Weschler, S.M. Criatividade e desempenho escolar: Uma síntese necessária. Linhas Críticas 2002, 8, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Collard, P.; Looney, J. Nurturing creativity in education. Eur. J. Educ. 2014, 49, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I. Investigating students’ beliefs about their preferred role as learners. Educ. Res. 2004, 46, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Alencar, E.M.L.S. Importância da criatividade na escola e no trabalho docente segundo coordenadores pedagógicos. Estud. Psicol. 2012, 29, 541–552. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/estpsi/v29n4/v29n4a09.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2019). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alencar, E.M.L.S. Inventário de Práticas Docentes que Favorecem a Criatividade no Ensino Superior. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2004, 17, 105–110. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/prc/v17n1/22310.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Berni, R.I.G. A Construção da Prática do Professor de Educação Infantil: Um Trabalho Crítico-Colaborativo. Master’s Thesis, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2007. Available online: https://sapientia.pucsp.br/handle/handle/13925 (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Oliveira, Z. Fatores influentes no desenvolvimento do potencial criativo. Estud. Psicol. 2010, 27, 83–92. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/estpsi/v27n1/v27n1a10 (accessed on 20 August 2019). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Burnard, P.; Dragovic, T. Collaborative creativity in instrumental group music learning as a site for enhancing pupil wellbeing. Camb. J. Educ. 2015, 45, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläveanu, V.P.; Clapp, E.P. Distributed and Participatory Creativity as a Form of Cultural Empowerment: The Role of Alterity, Difference and Collaboration. In Alterity, Values, and Socialization, Cultural Psychology of Education 6; Branco, A.U., Lopes-de-Oliveira, M.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 6, pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Slot, E.; Akkerman, S.; Wubbels, T. Adolescents’ interest experience in daily life in and across family and peer contexts. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 34, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapp, A. Interest, motivation and learning: An educational-psychological perspective. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 1999, 14, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 9, 75–78. Available online: https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura2000CDPS.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Ausubel, D.P. The Acquisition and Retention of Knowledge: A Cognitive View; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNaughton, G.; Hughes, P. Doing Action Research in Early Childhood Studies: A Step by Step Guide, 1st ed.; MacGrawHill: Berkshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McNiff, J.; Whitehead, J. All You Need to Know about Action Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Carlisle, UK, 2011; Available online: http://uk.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/39884_9780857025838.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2018).

- Chua, R.Y.J.; Morris, M.W.; Mor, S. Collaborating across cultures: Cultural metacognition and affect-based trust in creative collaboration. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2012, 118, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minayo, M.C.S. Análise qualitativa: Teoria, passos e fidedignidade. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2012, 17, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minayo MCS. Los conceptos estructurantes de la investigación cualitativa. Salud Colect. 2010, 6, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, J. Manual de Investigação Qualitativa em Educação; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2014; ISBN 978-989-26-0879-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G. Creativity as Research Practice in the Visual Arts. In International Handbook of Research in Arts Education; Bresler, L., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 16, Part 1; pp. 1181–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrower, F. Criatividade e Processos de Criação; Editora Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Stetsenko, A. Agentive creativity in all of us: An egalitarian perspective from a transformative activist stance. In Vygotsky and Creativity: A Cultural-Historical Approach to Play, Meaning Making, and the Arts, 2nd ed.; Connery, M.C., John-Steiner, V.P., Marjanovic-Shane, A., Eds.; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 41–60. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329281896 (accessed on 30 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- Gadotti, M. Escola Cidadã: Uma Aula sobre a Autonomia da Escola; Cortez: São Paulo, Brasil, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Niza, S. Sérgio Niza. Escritos sobre Educação; Tinta da China: Lisbon, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A. Complexidade e transdisciplinaridade em educação. Rev. Bras. Educ. 2008, 13, 71–83. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbedu/v13n37/07.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2020). [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varela, T.; Palaré, O.; Menezes, S. The Enhancement of Creative Collaboration through Human Mediation. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120347

Varela T, Palaré O, Menezes S. The Enhancement of Creative Collaboration through Human Mediation. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(12):347. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120347

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarela, Teresa, Odete Palaré, and Sofia Menezes. 2020. "The Enhancement of Creative Collaboration through Human Mediation" Education Sciences 10, no. 12: 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120347

APA StyleVarela, T., Palaré, O., & Menezes, S. (2020). The Enhancement of Creative Collaboration through Human Mediation. Education Sciences, 10(12), 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120347