The Impacts of Credit Standards on Aggregate Fluctuations in a Small Open Economy: The Role of Monetary Policy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Model

2.1. Households

2.2. Wholesale Good Entrepreneurs

2.3. Retailers

2.4. Banks

2.5. Importers and Incomplete Pass-Through

2.6. Central Bank

2.7. Demand for Exports

2.8. Equilibrium

3. Calibration

- 18 structural parameters: , , , v, , , , , , , d,, , , , and that appear in the steady-state system; and

- 13 structural parameters , , , , , , , , , , , , and that do not appear in the steady-state system.

4. Results

4.1. Dynamic Properties of the Models

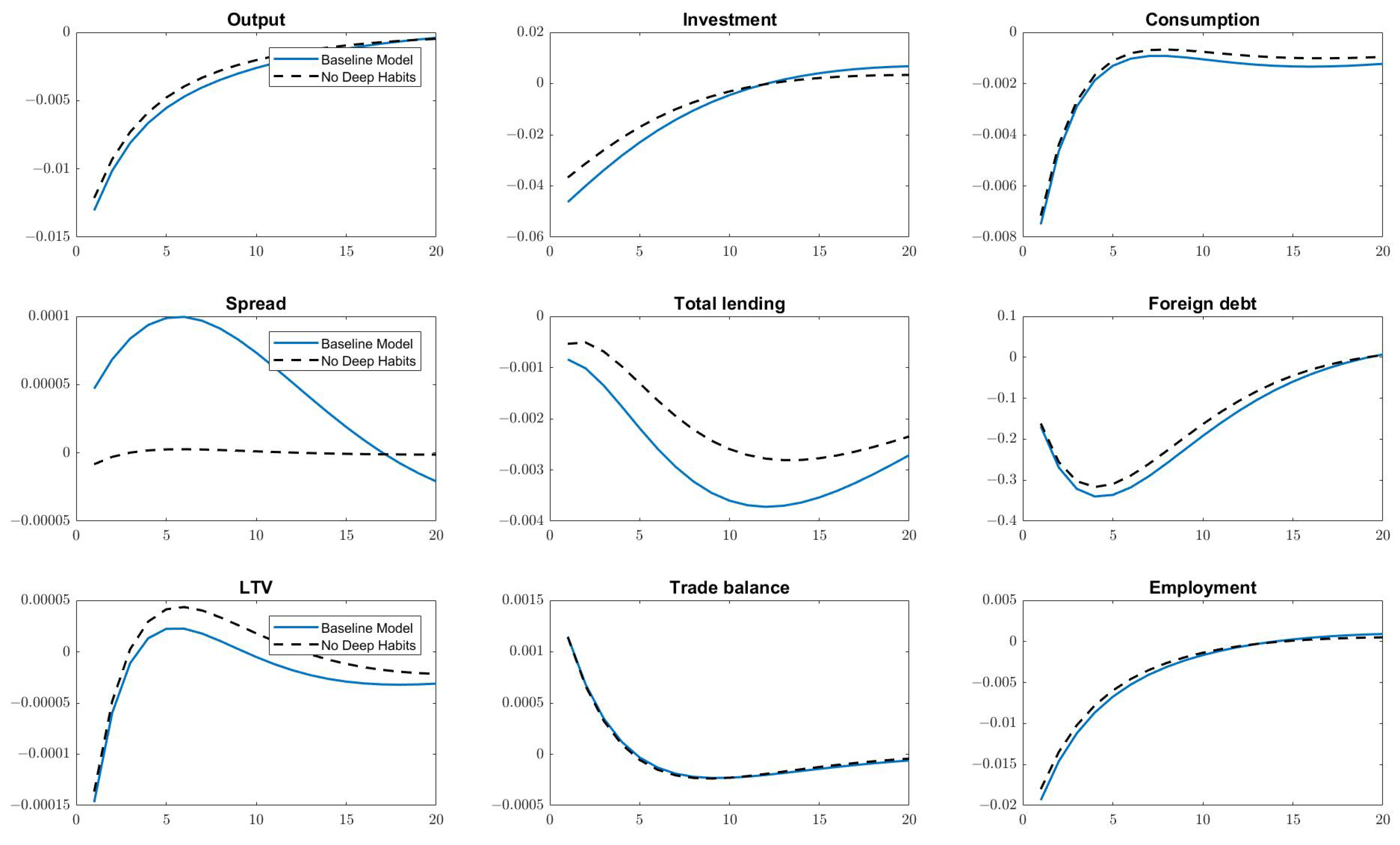

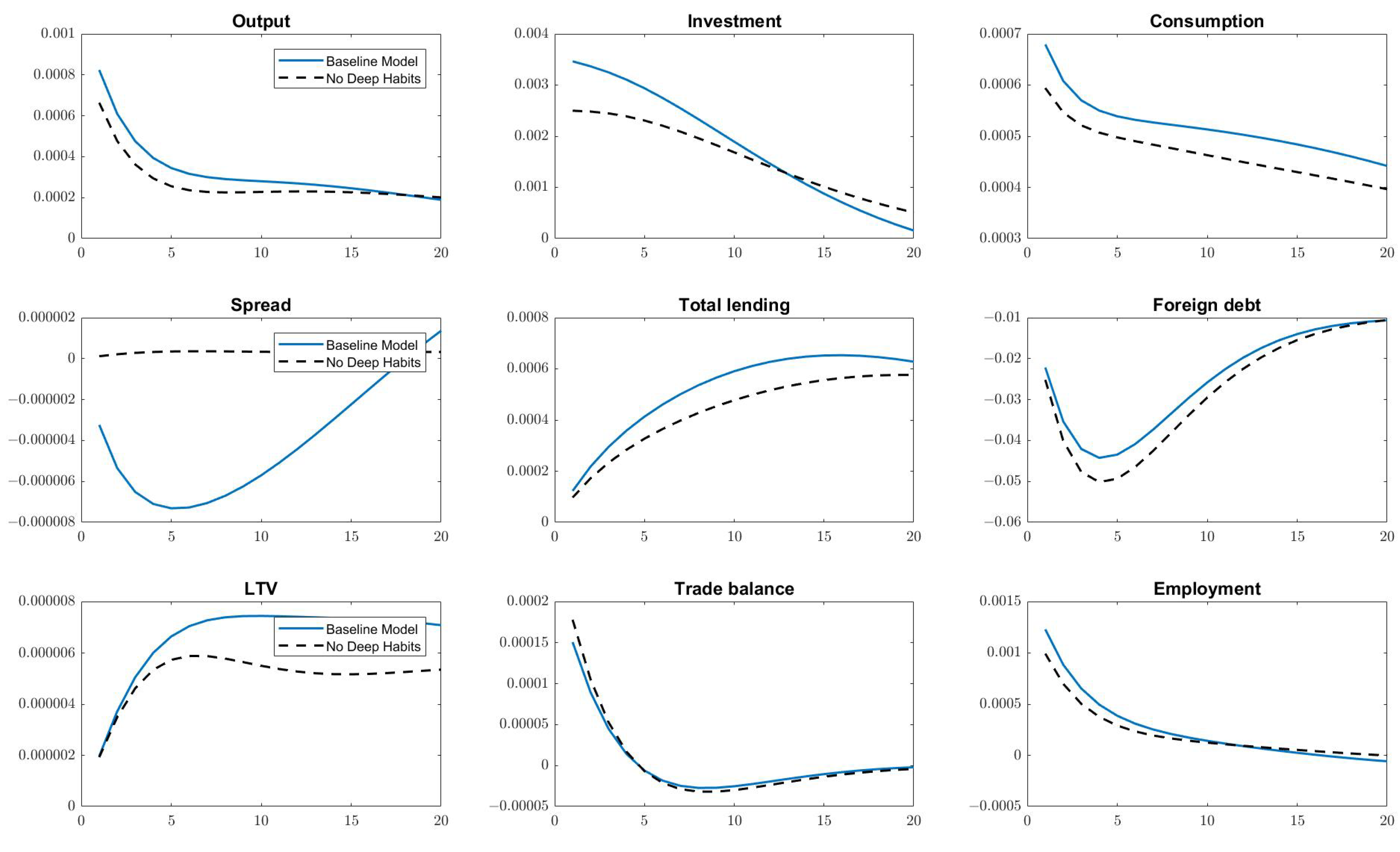

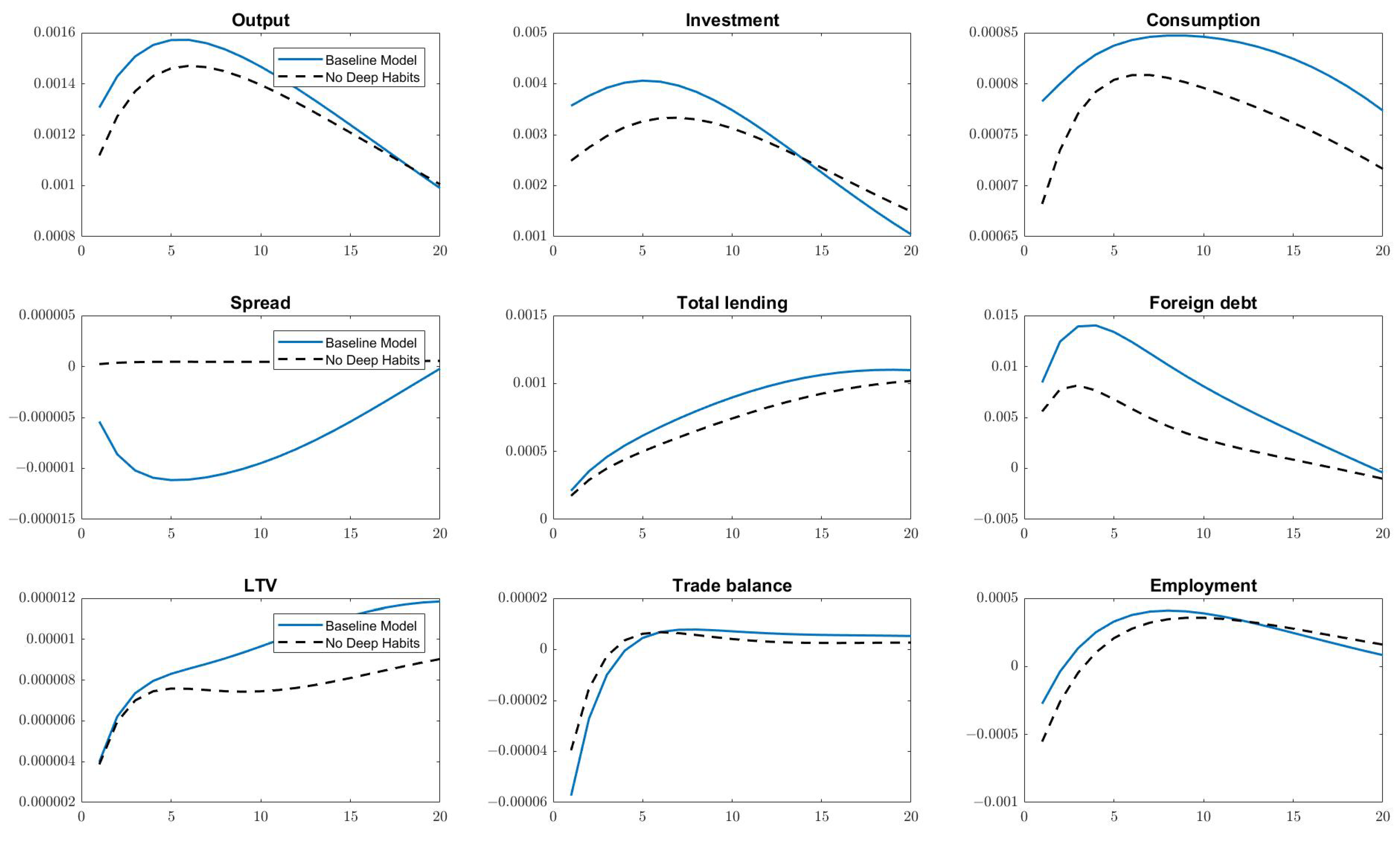

4.2. Impulse Response Analysis

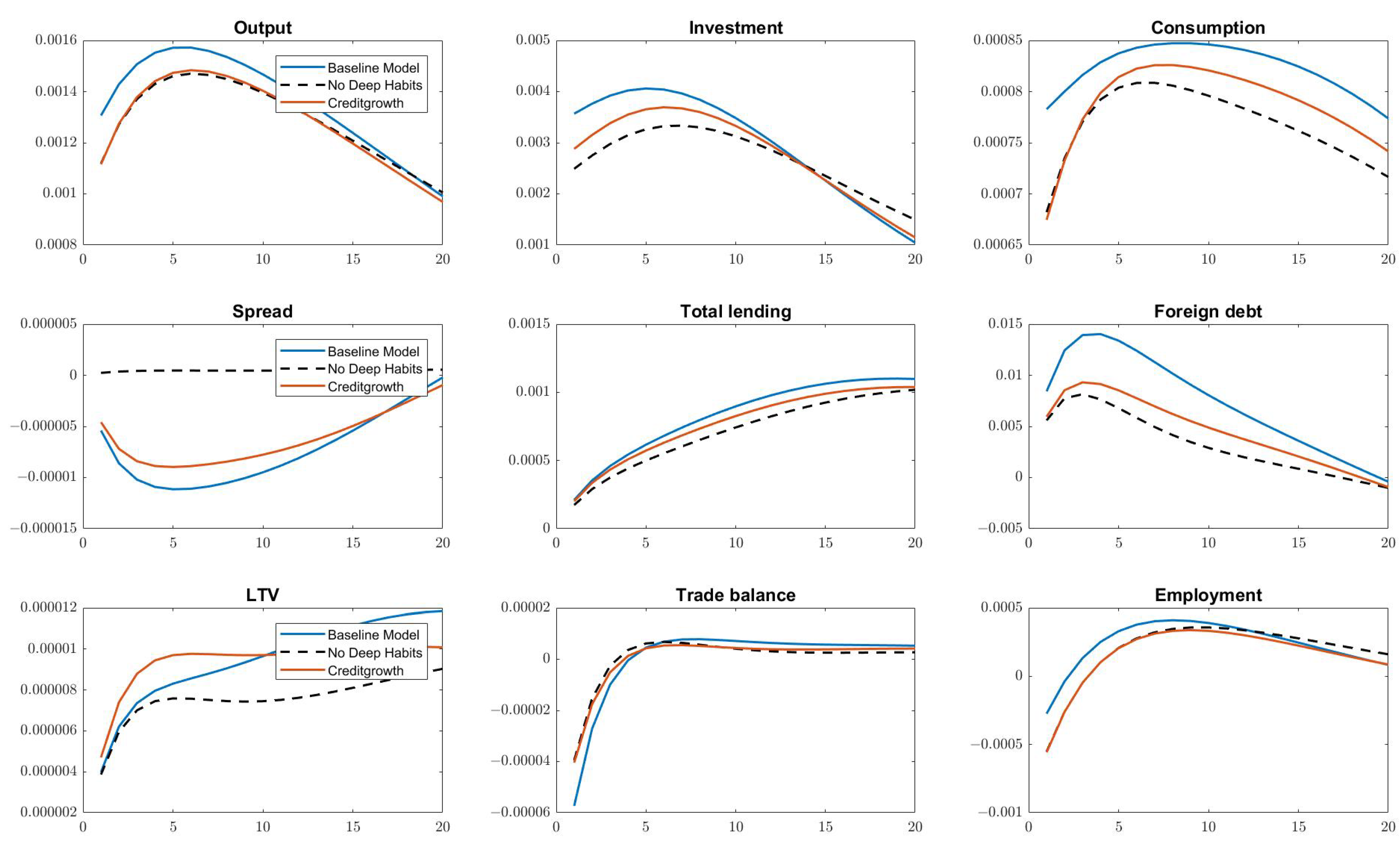

4.3. Deep Habits and Aggregate Fluctuations

4.4. Robustness Check

4.5. Policy

4.5.1. Aggregate Fluctuations

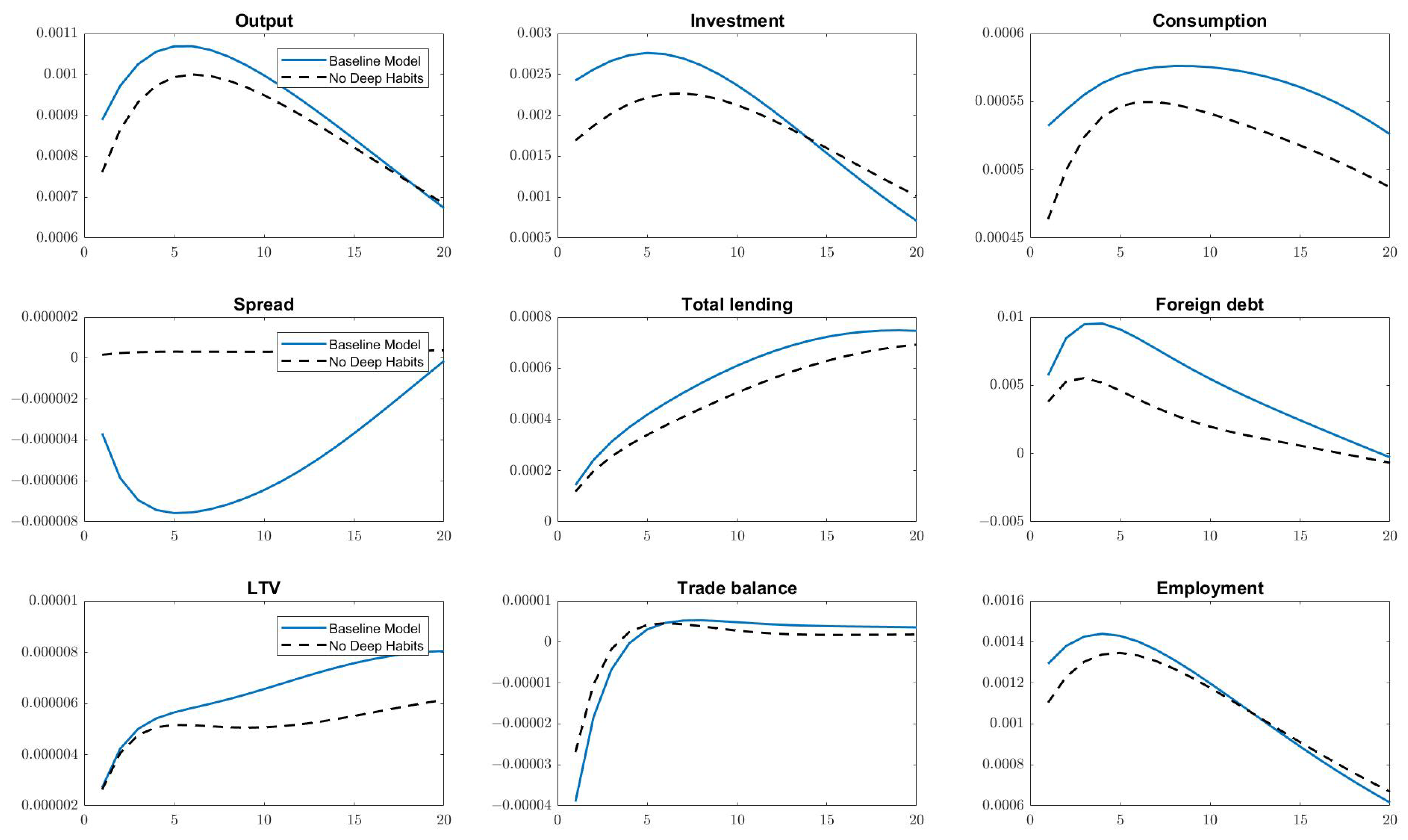

4.5.2. Impulse Response Analysis

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Several studies support this finding. For example, the Ref. (Aliaga-Díaz and Olivero 2010) points out that banks obtain an information monopoly over the creditworthiness of customers when they monitor borrowers, which triggers costs for borrowers to switch to other banks (switching costs). Deep habits, as proposed by (Ravn et al. 2006), can be indicated as a parsimonious way of incorporating switching costs into the dynamic general equilibrium model. Furthermore, the deep habits model can generate countercyclical credit standards, which is in line with empirical findings. The explanation is that an expansionary shock triggers an increase in output, and thus the demand for loans from entrepreneurs. In order to set the new bank spread, banks will consider the following trade-off: (1) Increasing the current profit by setting a higher spread; (2) generating a higher future market share by lowering the spread to attract more borrowers. Due to the persistence of the shock, the latter effect dominates the former one. As a result, a positive shock will lead to a lower credit spread. |

| 2 | We believe that bank competition on the amount of collateral that firms need to pledge is particularly relevant for the market of bank loans. The Ref. (Cerqueiro et al. 2016), using the difference-in-difference method for Swedish data, demonstrated that collateral is crucial for both borrowers and lenders and that with a high-quality collateral pledge, borrowers can experience a lower lending rate and an increase in credit availability. Furthermore, as the duration of the lending relationship increases, collateral requirements tend to relax. The Ref. (Berger and Udell 1995), for example, showed that a long relationship with banks reduces the probability of collateral pledging for borrowers. |

| 3 | For this study, we choose the Swedish economy to calibrate our models for the following reasons: First, Sweden is a small open economy with a floating exchange rate regime; thus, the fluctuation of the exchange rate could play an important role in the formulation of monetary policy. The Ref. (Bjørnland and Halvorsen 2014) provided empirical evidence to support this hypothesis. Specifically, by employing a structural VAR model with sign and zero restrictions, they found that monetary policy responds strongly to the movements in the exchange rate in the case of Sweden. Second, empirical studies demonstrate that credit standards in Sweden are countercyclical (see (Olivero 2010)). Therefore, investigating the impacts of credit standards on aggregate fluctuations in the Swedish economy is extremely important. Finally, as previously indicated, bank competition over the amount of collateral that entrepreneurs must pledge is particularly relevant for the Swedish bank loan market. |

| 4 | Various empirical studies support the viewpoint of Monacelli (see, e.g., (Campa and Goldberg 2005); (McCarthy 2007)). Moreover, the Ref. (Ferrero et al. 2008), using data from Sweden, Italy, and the United Kingdom, provided evidence on how import prices react to a sharp initial depreciation of the exchange rate and conclude that the pass-through on import prices is high, but with a delay. |

| 5 | Note that and are, in turn, composites of domestic differentiated goods and imported differentiated goods indexed by :

|

| 6 | The derivations of first-order conditions are available upon request. Following the standard literature in models with deep habits, we consider a symmetric equilibrium only. |

| 7 | For simplicity, we assume that the share of imported goods in the consumption basket of entrepreneurs is the same as that of households. |

| 8 | For simplicity, it is assumed that the LTV ratio allowed by bank b is the same for all entrepreneurs. |

| 9 | There are a number of reasons for entrepreneurs to minimize their collateral pledges. One crucial reason is that they do not want to lose control of assets in the event of default. Moreover, the process of asset valuation induces some additional costs, which entrepreneurs would prefer to avoid. It is worth noting that when is equal to zero, entrepreneurs are just concerned with the interest rate expenditure, as in (Aliaga-Díaz and Olivero 2010). |

| 10 | The actual borrowing, denoted by , is the amount that entrepreneur e will pay back to bank b in the following period. The effective loan, instead, demonstrates the fund available to that entrepreneur after deducting the switching costs to pay for investments, labor services, and so forth. |

| 11 | Analogous to consumption, investment is a composite index of domestic and foreign goods, that is, . and are, in turn, composite indexes of domestic and imported differentiated goods, respectively. Following (Galí and Monacelli 2016), we assume that the share of imported goods in the investment basket is the same as that in the consumption basket for simplifying reasons. |

| 12 | represents the difference between effective and actual borrowings, while indicates the wedge between the effective and actual repayment of loans. is the probability of repayment and the parameter captures the fact that the value of the collateral is lower in liquidation, as we discuss in more detail in the banking sector. The two lump-sum transfers are to guarantee that all markets clear. |

| 13 | Since we assume that retailers involve no cost at differentiating goods and that each retailer is matched to one entrepreneur randomly, the following equation must hold for all time t: . |

| 14 | This assumption renders our analysis of entrepreneurs’ problems simpler, as pointed out by (Bernanke et al. 1999). |

| 15 | In the symmetric equilibrium, we have . |

| 16 | The total amount of loans is defined as . |

| 17 | Following (Ravn 2016), we assume that a fraction of bank b’s loans to a specific entrepreneur relative to the total loans of that bank is equivalent to a fraction of that bank’s total loans relative to the total loans of all banks in the economy . Furthermore, it is assumed that a lump-sum transfer is made to entrepreneurs for compensation of handing over their assets in order to guarantee that no money falls out of the economy. |

| 18 | For simplicity, we assume that entrepreneurs do not internally consider that they can not pay back the loans with some positive probability. This implies that when offering loans to entrepreneurs, the bank recognizes that a proportion of the total loans will end up not being repaid ex-post, while each entrepreneur simply thinks that they can repay the loan they obtain. The wedge between effective and actual repayment of loans arising from this assumption ends up in the lump-sum transfer earned by the entrepreneur. The more credit standards are relaxed, the larger the wedge becomes. |

| 19 | Each bank also faces a trade-off when choosing its lending rate: while raising the lending rate leads to higher profits, it comes at the cost of losing market share as entrepreneurs switch to other banks. |

| 20 | We impose the condition , for all t because prices are assumed to be flexible in the world economy. Therefore, the marginal cost is the same for all importers as in (Monacelli 2005). |

| 21 | Note that measures the deviation from the law of one price. When we shut down the incomplete pass-through feature, the law of one price holds, that is, for all t. |

| 22 | This assumption is reasonable because the Sveriges Riksbank (the central bank of Sweden) has introduced the inflation target since 1993. |

| 23 | The aggregate export is produced via the following technology: , where is the export good j. |

| 24 | In fact, we consider a semi-symmetric equilibrium as in (Airaudo and Olivero 2019). On one hand, we assume that all households in the consumption sector, all wholesale goods entrepreneurs in the producing sector, and all banks in the financial sector do behave identically. On the other hand, we assume that price is sticky in the retail sector. Specifically, there exists a faction of of retailers that can reoptimize their prices, whereas a fraction of cannot. As a result, the pricing is different among domestic retailers. A similar assumption is applied to the imported sector. A full list of equilibrium conditions is available upon request. The model is linearized and solved using DYNARE (Adjemian et al. 2011). |

| 25 | Note that a significant difference between discount factors is to guarantee that in the steady-state, the collateral constraint is binding, that is, . Interested readers are referred to (Gerali et al. 2010) for a more detailed discussion. |

| 26 | This is also in line with (Booth and Booth 2006), who find that the concern about collateral minimization is of limited importance to firms. Therefore, we assign a small value of 0.05, and later we report a robustness check for this parameter. |

| 27 | Since there is no consensus on the trade elasticity of substitution in the literature, we also check the sensitivity of our results for different values of this parameter. |

| 28 | We use the quarterly data over the period 1993Q1-2018Q3 for the real U.S. GDP. The series is then detrended by the log quadratic method, as in (Uribe and Schmitt-Grohé 2017). |

| 29 | The value of collateral retrieved in liquidation is re-calibrated so that the steady-state of the LTV ratio remains unchanged at 0.75. |

| 30 | In each exercise, the value of collateral retrieved in liquidation is re-calibrated if necessary to guarantee that the regulatory LTV remains unchanged at 0.75. |

| 31 | In fact, there are very small increases as we (numerically) increase the value of this elasticity from to . In other words, deep habits induce larger effects as this elasticity is (numerically) higher. This seems confusing because given the relaxation of credit standards, it is more costly for banks to give loans in light of repayment probability when the elasticity is (numerically) higher, making banks less appealing. However, in this case, we have to increase the value of to keep the LTV ratio unchanged at 0.75, which offsets the negative effect of the (numerically) larger elasticity on the cost of a marginal increase in LTV ratio. |

| 32 | The monetary rule has recently been modified to include several aspects of the open economy, such as the exchange rate and foreign interest rate. The Ref. (Lim and McNelis 2008) demonstrated that the domestic interest rate moves along with the foreign interest rate due to the activity of arbitrage and the assumption of a small open economy. The Ref. (Agyapong 2021), introducing the real exchange rate in the policy rule, investigated the effectiveness of the Taylor rule in predicting exchange rates. |

| 33 | Similar results are obtained for the two remaining policies. The explanation is as follows: By allowing the policy rate to react to changes in the foreign interest rate (or changes in the exchange rate), the central bank can indirectly counteract the fluctuations of lending through controlling foreign debt. As a consequence, less credit is poured into the economy during the boom, damping the impact of credit standards on aggregate fluctuations. |

References

- Adjemian, Stéphane, Houtan Bastani, Michel Juillard, Ferhat Mihoubi, George Perendia, Marco Ratto, and Sébastien Villemot. 2011. Dynare: Reference Manual, Version 4. Paris: Dynare. [Google Scholar]

- Afrin, Sadia. 2020. Does oligopolistic banking friction amplify small open economy’s business cycles? Evidence from Australia. Economic Modelling 85: 119–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, Joseph. 2021. Application of Taylor rule fundamentals in forecasting exchange rates. Economies 9: 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airaudo, Marco, and María Pía Olivero. 2019. Optimal monetary policy with countercyclical credit spreads. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 51: 787–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga-Díaz, Roger, and María Pía Olivero. 2010. Macroeconomic implications of “deep habits” in banking. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 42: 1495–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga-Díaz, Roger, and María Pía Olivero. 2011. The cyclicality of price-cost margins in banking: An empirical analysis of its determinants. Economic Inquiry 49: 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asea, Patrick K., and Brock Blomberg. 1998. Lending cycles. Journal of Econometrics 83: 89–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, Robert J. 1976. The loan market, collateral, and rates of interest. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 8: 439–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Allen N., and Gregory F Udell. 1995. Relationship lending and lines of credit in small firm finance. Journal of Business, 351–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernanke, Ben S., Mark Gertler, and Simon Gilchrist. 1999. The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework. In Handbook of Macroeconomics. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 1, pp. 1341–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnland, Hilde C., and Jørn I Halvorsen. 2014. How does monetary policy respond to exchange rate movements? New international evidence. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 76: 208–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Booth, James R., and Lena Chua Booth. 2006. Loan collateral decisions and corporate borrowing costs. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 38: 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, Jose Manuel, and Linda S. Goldberg. 2005. Exchange rate pass-through into import prices. Review of Economics and Statistics 87: 679–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueiro, Geraldo, Steven Ongena, and Kasper Roszbach. 2016. Collateralization, bank loan rates, and monitoring. The Journal of Finance 71: 1295–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes, Luis Felipe, Roberto Chang, and Andres Velasco. 2004. Balance sheets and exchange rate policy. American Economic Review 94: 1183–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christiano, Lawrence J., Mathias Trabandt, and Karl Walentin. 2011. Introducing financial frictions and unemployment into a small open economy model. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 35: 1999–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrero, Andrea, Mark Gertler, and Lars EO Svensson. 2008. Current Account Dynamics and Monetary Policy. Technical Report. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Gali, Jordi, and Tommaso Monacelli. 2005. Monetary policy and exchange rate volatility in a small open economy. The Review of Economic Studies 72: 707–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galí, Jordi, and Tommaso Monacelli. 2016. Understanding the gains from wage flexibility: The exchange rate connection. American Economic Review 106: 3829–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerali, Andrea, Stefano Neri, Luca Sessa, and Federico M. Signoretti. 2010. Credit and banking in a DSGE model of the Euro area. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 42: 107–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, Matteo. 2005. House prices, borrowing constraints, and monetary policy in the business cycle. American Economic Review 95: 739–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jimenez, Gabriel, Vicente Salas, and Jesus Saurina. 2006. Determinants of collateral. Journal of Financial Economics 81: 255–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiyotaki, Nobuhiro, and John Moore. 1997. Credit cycles. Journal of Political Economy 105: 211–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, Robert. 2001. The exchange rate in a dynamic-optimizing business cycle model with nominal rigidities: A quantitative investigation. Journal of International Economics 55: 243–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, Guay C., and Paul D. McNelis. 2008. Computational Macroeconomics for the Open Economy. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lindé, Jesper. 2003. Comment on “the output composition puzzle: A difference in the monetary transmission mechanism in the Euro area and US”. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 35: 1309–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zheng, Pengfei Wang, and Tao Zha. 2013. Land-price dynamics and macroeconomic fluctuations. Econometrica 81: 1147–84. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Jonathan. 2007. Pass-through of exchange rates and import prices to domestic inflation in some industrialized economies. Eastern Economic Journal 33: 511–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melina, Giovanni, and Stefania Villa. 2014. Fiscal policy and lending relationships. Economic Inquiry 52: 696–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melina, Giovanni, and Stefania Villa. 2018. Leaning against windy bank lending. Economic Inquiry 56: 460–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendoza, Enrique G. 1991. Real business cycles in a small open economy. The American Economic Review 81: 797–818. [Google Scholar]

- Monacelli, Tommaso. 2005. Monetary policy in a low pass-through environment. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 37: 1047–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olivero, Maria Pia. 2010. Market power in banking, countercyclical margins and the international transmission of business cycles. Journal of International Economics 80: 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn, Morten, Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé, and Martin Uribe. 2006. Deep habits. The Review of Economic Studies 73: 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravn, Søren Hove. 2016. Endogenous credit standards and aggregate fluctuations. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 69: 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Joao A. C., and Andrew Winton. 2008. Bank loans, bonds, and information monopolies across the business cycle. The Journal of Finance 63: 1315–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt-Grohé, Stephanie, and Martın Uribe. 2003. Closing small open economy models. Journal of International Economics 61: 163–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shapiro, Alan Finkelstein, and Maria Pia Olivero. 2020. Lending relationships and labor market dynamics. European Economic Review 127: 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, Frank, and Rafael Wouters. 2007. Shocks and frictions in US business cycles: A Bayesian DSGE approach. American Economic Review 97: 586–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uribe, Martin, and Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé. 2017. Open Economy Macroeconomics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Preference parameters | ||

| 0.9994 | Discount factor for households | |

| 0.95 | Discount factor for entrepreneurs | |

| Z | 2.63 | steady-state of labor supply shock |

| 0.6 | Consumption habits for housholds | |

| 0.6 | Consumption habits for entrepreneurs | |

| 6 | Elasticity of substitution across goods | |

| Production parameters | ||

| 0.32 | Capital share in production | |

| 0.025 | Depreciation rate of capital | |

| 2.58 | Capital adjustment cost | |

| 0.8 | Calvo index for domestic price | |

| 0.8 | Calvo index for imported price | |

| 0.05 | Relative weight of collateral optimization | |

| Banking parameters | ||

| 0.72 | Deep habits formation | |

| 0.85 | Persistence of deep habits stock | |

| 230 | Elasticity of substitution for banks | |

| 0.989 | steady-state probability of repayment | |

| −1.5 | Elasticity of repayment probability | |

| 0.9425 | Recovery rate of assets | |

| Openness parameters | ||

| v | 0.3759 | Degree of openness |

| 2 | Trade elasticity of substitution | |

| 1.01 | World interest rate | |

| −0.0094 | Constant component of country premium | |

| 0.18 | Debt elasticity interest rate | |

| d | 0.01 | Foreign debt parameter |

| 1.244 | steady-state of foreign shock | |

| Policy parameters | ||

| 1.005 | steady-state gross inflation target | |

| 0.819 | Interest rate smoothing | |

| 1.909 | Response to the deviation of inflation | |

| Shock parameters | ||

| 0.9579 | Persistence of foreign shock | |

| 0.0031 | SD of foreign shock | |

| 0.95 | Persistence of technology shock | |

| 0.0015 | SD of technology shock | |

| 0.95 | Persistence of labor supply shock | |

| 0.0015 | SD of labor suppy shock | |

| 0.00075 | SD of monetary shock |

| Data | Deep Habits Model | No Deep Habits Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard deviation | |||

| Output | 2.38 | 2.38 | 2.16 |

| Relative standard deviation to output | |||

| Consumption | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| Investment | 2.33 | 3.77 | 3.13 |

| Export | 2.59 | 1.12 | 1.13 |

| Import | 2.54 | 0.79 | 0.81 |

| Correlation with output | |||

| Consumption | 0.59 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| Investment | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.93 |

| Export | 0.81 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Import | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| Spread | −0.28 | -0.67 | – |

| Autocorrelation coefficients | |||

| Output | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.82 |

| Consumption | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| Investment | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| Export | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| Import | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Spread | 0.69 | 0.98 | 0.66 |

| Variance Ratio | |

|---|---|

| Output | 1.21 |

| Total investment | 1.76 |

| Total consumption | 1.16 |

| Lending | 1.32 |

| Employment | 1.20 |

| Foreign debt | 1.22 |

| Trade balance | 1.03 |

| Variance Ratio | Output | Investment | Consumption | Lending | Employment | Debt | Trade Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1.21 | 1.76 | 1.16 | 1.32 | 1.20 | 1.22 | 1.03 |

| 1.21 | 1.76 | 1.16 | 1.31 | 1.20 | 1.22 | 1.03 | |

| 1.22 | 1.76 | 1.17 | 1.32 | 1.20 | 1.22 | 1.03 | |

| 1.01 | 1.14 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.95 | |

| 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 | |

| 1.28 | 1.98 | 1.22 | 1.40 | 1.26 | 1.29 | 1.06 | |

| 1.15 | 1.54 | 1.11 | 1.23 | 1.14 | 1.15 | 1.00 | |

| 1.20 | 1.74 | 1.13 | 1.32 | 1.19 | 1.18 | 0.94 | |

| 1.22 | 1.77 | 1.18 | 1.31 | 1.21 | 1.27 | 1.09 | |

| 1.22 | 1.76 | 1.17 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 1.23 | 1.04 | |

| 1.21 | 1.76 | 1.16 | 1.32 | 1.20 | 1.22 | 1.02 |

| Credit growth augmented monetary policy | ||||

| Variance ratio | ||||

| Output | 1.18 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 0.94 |

| Total investment | 1.71 | 1.52 | 1.44 | 1.33 |

| Total consumption | 1.14 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 0.93 |

| Lending | 1.28 | 1.16 | 1.11 | 1.04 |

| Employment | 1.16 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 0.91 |

| Foreign debt | 1.18 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 0.93 |

| Trade balance | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.80 |

| Foreign interest rate augmented monetary policy | ||||

| Variance ratio | ||||

| Output | 1.19 | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.01 |

| Total investment | 1.72 | 1.59 | 1.53 | 1.44 |

| Total consumption | 1.15 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.00 |

| Lending | 1.29 | 1.19 | 1.14 | 1.08 |

| Employment | 1.18 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 0.99 |

| Foreign debt | 1.19 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.00 |

| Trade balance | 1.01 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.86 |

| Exchange rate augmented monetary policy | ||||

| Variance ratio | ||||

| Output | 1.19 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.00 |

| Total investment | 1.72 | 1.59 | 1.52 | 1.43 |

| Total consumption | 1.14 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 0.99 |

| Lending | 1.30 | 1.24 | 1.21 | 1.16 |

| Employment | 1.17 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.97 |

| Foreign debt | 1.19 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 0.97 |

| Trade balance | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.81 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le, H. The Impacts of Credit Standards on Aggregate Fluctuations in a Small Open Economy: The Role of Monetary Policy. Economies 2021, 9, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040203

Le H. The Impacts of Credit Standards on Aggregate Fluctuations in a Small Open Economy: The Role of Monetary Policy. Economies. 2021; 9(4):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040203

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe, Hai. 2021. "The Impacts of Credit Standards on Aggregate Fluctuations in a Small Open Economy: The Role of Monetary Policy" Economies 9, no. 4: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040203

APA StyleLe, H. (2021). The Impacts of Credit Standards on Aggregate Fluctuations in a Small Open Economy: The Role of Monetary Policy. Economies, 9(4), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040203