1. Introduction

The Regulation of the (European) audit market has a long tradition (e.g.,

Evans and Honold 2007;

Humphrey et al. 2011;

Naumann 2014), even before the Fourth Directive in 1978 (78/660/EEC) was implemented. Over the past few decades, the regulation of this important profession has repeatedly been a political issue. The starting points for these measures were, on the one hand, several harmonization efforts within European commercial and corporate law and, on the other hand, various scandals, and economic crises (e.g., in Germany, the real estate entrepreneur

Schneider (see e.g.,

Herzig and Watrin 1995) or

Philipp Holzmann AG, (see e.g.,

Wolz 2004). The regulation of the European audit market was not isolated from developments in the United States, where various measures to regulate the audit market were taken as a pilot for other countries, particularly after the “Enron-scandal” and the resulting collapse of the audit firm

Arthur Andersen, within the framework of the resulting “Sarbanes-Oxley Act” (SOX,

Coates 2007).

The issue of the regulation of auditors is of particular interest in view of the latest scandal involving the payment service provider,

Wirecard AG (

Zeit Online 2020). According to recent media reports, the role of the auditing company EY is also being scrutinized in this context. The German Finance Minister, Olaf Scholz, for instance, felt the need to consider stronger financial regulation and oversight of the auditing profession. In addition to the possibility of a more distinct separation between the auditing and consulting businesses (possibly the introduction of pure audit firms), Scholz specifically questions the recently introduced maximum term for the auditing of annual financial statements (

Zeit Online 2020). He does not object to the introduction of obligatory change of auditor after a certain period of time, but rather strongly favors shorter rotation periods than currently exist.

Since 2007, the financial industry, the so-called “real economy” and governments have been struggling with the aftermath of the last financial crisis (e.g.,

Barth et al. 2010;

Rudolph 2010). Although there were multiple causes, government action in the form of more lenient monetary policy in combination with fair value accounting is seen as a major culprit (e.g.,

Huerta de Soto 2009;

Hering et al. 2010;

Brösel et al. 2012; on the problems of fair value accounting see further, e.g.,

Biondi 2011;

Braun 2019). The European institutions have concluded that, in addition to close monitoring of the financial sector (e.g.,

Kaserer 2010;

Davies 2015), the auditing market must also undergo fundamental changes. As part of the reform process of the recent global financial and economic crisis, further and stricter regulatory measures were taken. The purpose of these fundamental market reforms was intended to regain public confidence in the audit profession after several scandals and crises (e.g.,

Daniels and Booker 2011;

Tan and Ho 2016).

Our analysis needs to be based on real-world circumstances, and in the real world, government interventions play an increasingly important role (e.g.,

Kurrild-Klitgaard 2005). However, it is also well known in the economic literature that government intervention does not solve problems, but on the contrary can exacerbate problems (e.g.,

Mises 1926,

1957,

1998). If we take the example of central bank control of interest rates or fractional reserve banking, it is precisely these interventions that lead to renewed crises. Ludwig von Mises described this early on as an intervention spiral, so that a dynamic process toward a planned economy is set in motion (see further on this problem, e.g.,

Bagus 2011,

2013,

2015).

Regarding these events, the European Union introduced a mandatory (external) auditor rotation for public interested entities (PIE) (e.g.,

Tan and Ho 2016), which are defined as entities which are of significant public interest by virtue of their fields of activity, their size, or the number of their employees, or which have a large number of shareholders due to their corporate forms (in the following: “EU audit market reform”). Apart from banks and insurance companies, these include above all listed corporations within the EU (e.g.,

Widmann and Wolz 2019). The primary objective of the EU audit market reform is the improvement of both the quality of the audit as well as the significance of the auditor’s reporting. The EU believes that the quality of the audit can be increased if the independence of the statutory auditor is sustainably strengthened.

At this stage, we first refer to the comprehensive study by

Willekens et al. (

2019), which already describes various effects of EU audit market reform. In this study, the effects on costs, concentration, and competition on the audit market are mainly presented. However, the aspect of audit firm tenure was not considered. Second, we refer to another study by Audit

Analytics (

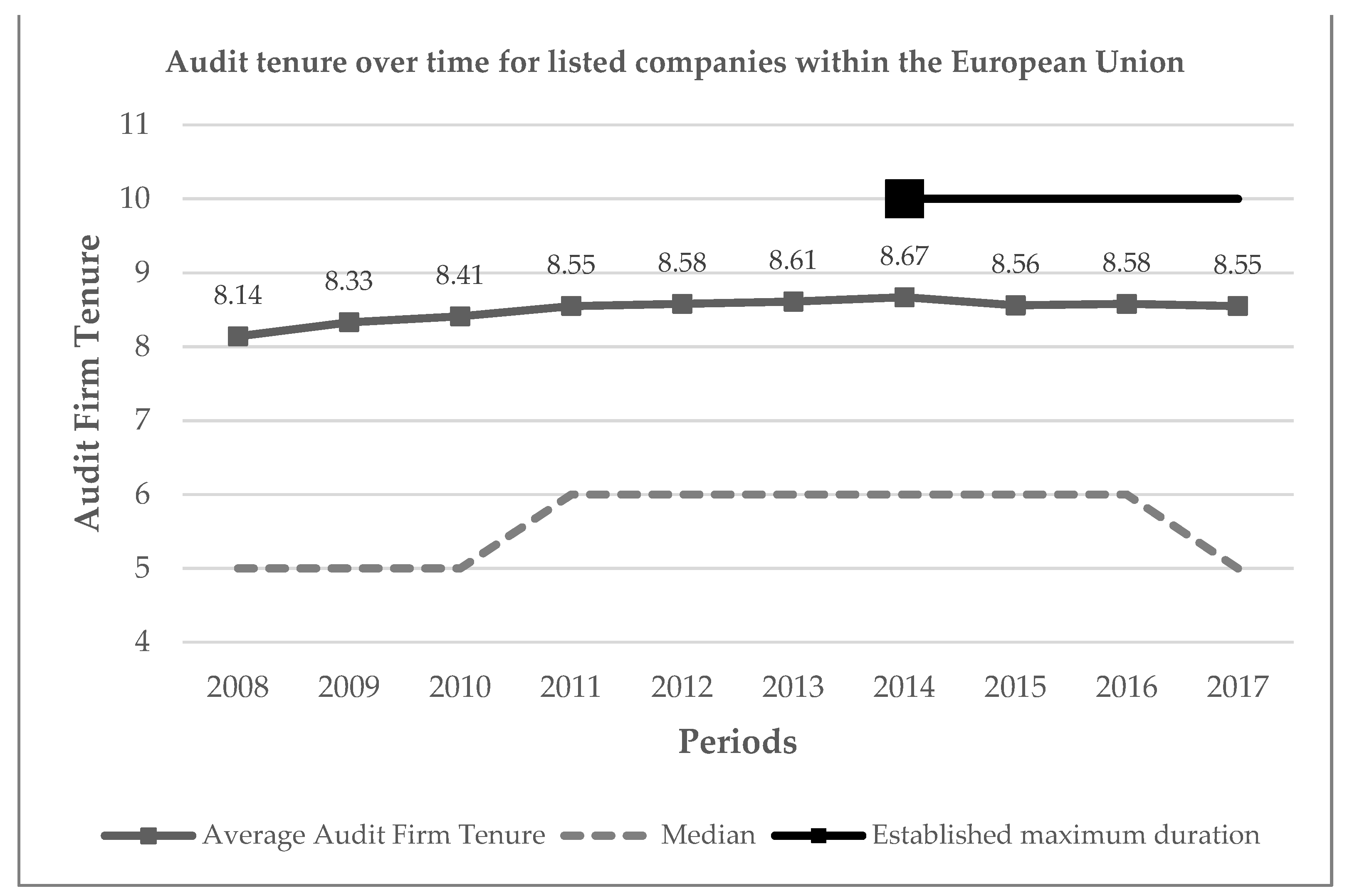

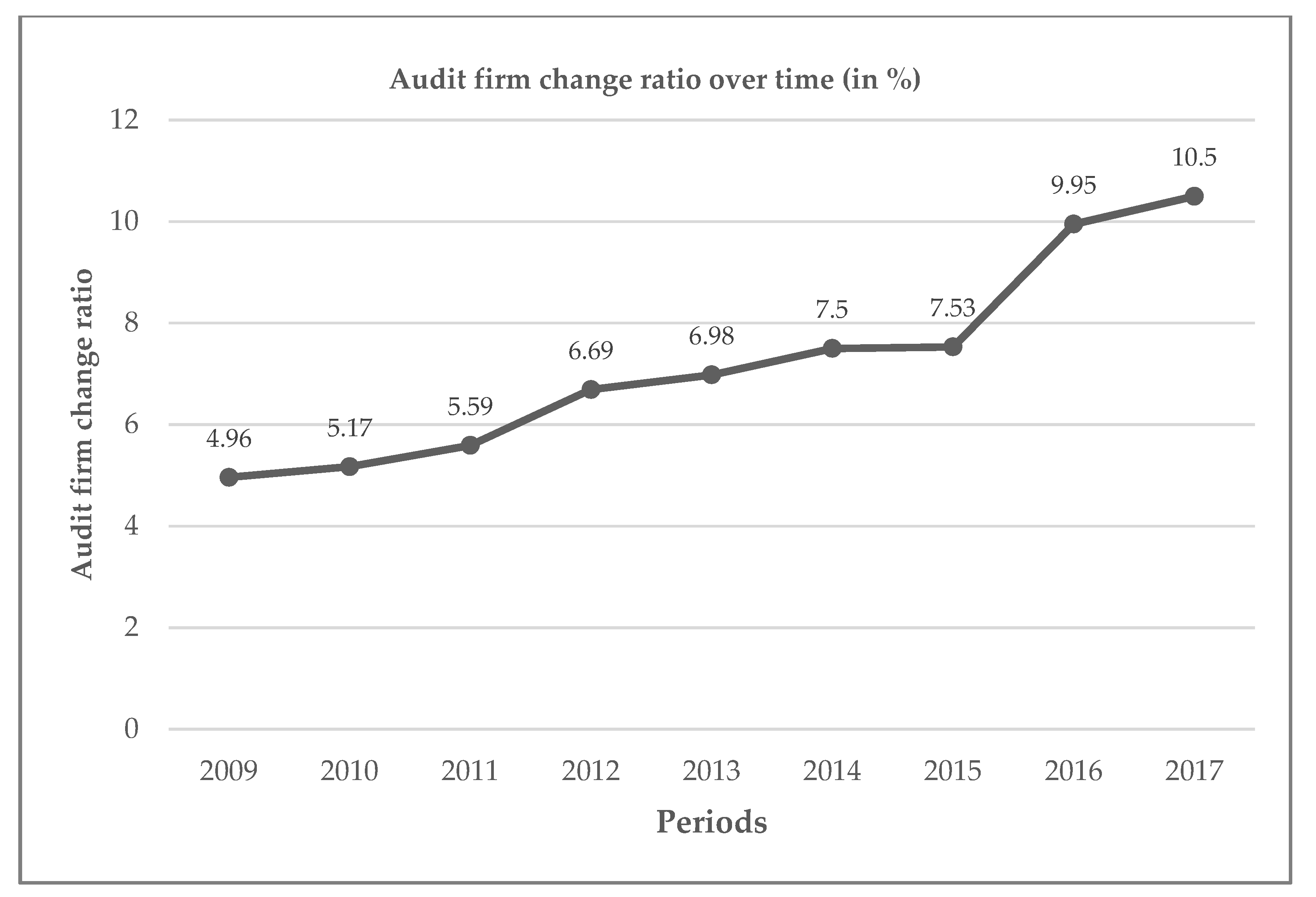

2020) that had already published these audit firm tenure data from PIE within the EU. However, their presented dataset covers recently published financial statement data without academic discussion. Furthermore, and due to the up-to-date mentioned dataset, the effects of the EU audit market reform already applied to these results. Within our paper we will compare audit firm tenure data collected from financial statements of listed entities within the EU before and after the introduction of the EU audit market reform in 2014 and 2016 and discuss in detail the decision by politicians to establish maximum durations.

Against the background of a classical liberal position and the idea of free competition as a fundamental freedom of the European Union, the central definition of maximum terms must be discussed critically. In particular, the member states differ in terms of their legal, economic, and cultural conditions. According to

Brooks et al. (

2017), the optimal audit firm tenure should depend on the legal regime of a country and especially on investor protection. They point out the implication that longer auditor tenure would be favorable for countries with a strong system of investor protection. Given this, it would be interesting to conduct further research and compare auditor tenure in each European country with strictness of company law.

Hayek (

1945) emphasizes the decentralization of regulations in general, including decentralized distribution of knowledge within a society. Especially, decentralized regulation of the profession would be the most preferable. Nevertheless, it is also the task of science to take existing conditions as given and evaluate them. This is the central aim of the present paper. To accomplish this, we used empirical data to analyze the structure of the currently valid rotation system for auditors across the EU against the background of recent demands for a shorter maximum term of mandate.

In deciding to establish a maximum duration for audit engagements, an adequate tenure needs to be defined. Bear in mind that the EU intended to stimulate the audit market by making the decision to establish an audit firm rotation system. This action will only lead to significant changes in the market and a reduction of audit firm tenure when the average of the tenure of audit engagements at that time exceeds the agreed-upon maximum duration. Our paper does not discuss audit firm rotation as a measure to stimulate the market—our objective is much more based on the following research questions (RQ):

RQ 1: Is there a connection between the political decision by the EU to set a specific point value as maximum duration and empirical results?

RQ 2: What effect has Regulation (EU) No. 537/2014 had, and continues to have, when and since it was published?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: In

Section 2 we outline the theoretical and political background, in particular the main goals of the EU reform of the audit market and their potential consequences from an economic point of view. In

Section 3 of the paper, we present empirical evidence. We evaluate the established maximum duration set by the European Union based on a unique dataset considering all available listed companies within the EU with respect to their auditor tenure over time. In the following

Section 4 the newly installed maximum durations, by referring to the origins and the different perspectives of the participating entities within the EU at that time, will be discussed from a politico-economic perspective.

Section 5 provides an outlook on further research.

Overall, we would like to contribute to a broader discussion concerning the regulation of the European audit market that could integrate the perspective of Public Choice to provide new insights about political interventionism in the market. Based on our extensive dataset we ask the provocative question whether 10 years are more are “proven or popular”? With respect to our data, the findings at least give a first indication of the latter.

4. Discussion from the Perspective of Public Choice

Taking the agreed maximum duration of 10 years before mandatory audit firm rotation into consideration, we want to look back at the origins of the regulation. Prior to the final regulation the respective European institutions all made their own proposals regarding a potential maximum duration of audit engagements. With respect to the organizational structure of the EU, we identify three institutions that determine political decisions within the union, and therefore, the legal regulation of the European audit market. By assuming the EU as a collective that must decide based on the preferences of the three institutions, the EU Commission, EU Parliament, and EU Council of Ministers, we provide a possible explanation based on the Public Choice framework for collective decision-making by

Buchanan and Tullock (

1962) (further, as an overview and application,

Follert et al. 2020, esp. 5–13). Within the Buchanan and Tullock model, collective decision-making is modeled as a consensus. The different institutions (members) that are involved in a decision-making process tend to have different interests and the rules of a process can help to reduce this conflict. Divergent interests seem to be evident also for the different institutions within the EU, in particular regarding the different member states and the different interests between governments (here Council of Ministers) and population(s) (here Parliament) (

Downs 1957). Therefore, we would like to discuss the maximum duration within the EU regulation as a result of a consent between three institutions with particular interests that is shown graphically in

Figure 4.

Perspective of the EU Commission

The EU Commission presented a proposal for a reform package based on a directive and a regulation on 30 November 2011. This proposal provided for a mandatory maximum duration of 6 years. However, an extension option up to nine years was suggested, provided that the audit would be carried out jointly by two audit firms. (Art. 33 of the proposal for a Directive by EU Commission 2011).

At that time (2011), and considering the proposed maximum duration of 6 years, all member states except Italy, Croatia, Luxemburg, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia would have been affected by the rotation requirement. Apart from the last-mentioned member states, all others had average auditor tenures of more than six years.

Perspective of the EU Parliament

The European Parliament responded with its own proposal considering a maximum duration of 14 years for audit engagements and after rounds of negotiations about the maximum duration that should be established (see

Naumann and Herkendell 2013, as the original document is no longer available).

At that time (2013), and considering the proposed maximum duration of 14 years, there was no member state that would have been affected on average by that rotation requirement, since all had average auditor tenures of less than fourteen years.

Perspective of EU Council of Ministers

In addition to this, the EU Council of Ministers followed through on the reforms by suggesting 10 years as a maximum period. Therefore, an informal trialogue process had to be convened between the European Parliament and the EU Council of Ministers, where the EU Commission played the role as a mediator to find a consensus (see

Naumann and Herkendell 2013, as the original document is no longer available).

Given the agreed duration of 10 years as stated in Article 17 of EU Regulation No. 537/2014, it seems more than doubtful that this value was chosen based on empirical evidence. Regarding the maximum duration of 6 years, as proposed by the EU Commission, the head of the audit unit in the Directorate General of the Internal Market and Services of the European Commission made the following statement to the PCAOB while in attendance at a public meeting about auditor independence and audit firm rotation in the US, as of 18 October 2012 (see

PCAOB 2012):

“We have proposed six years in case of solo audits and nine years in case of joint audits. We see some proposing maybe ten years, and of course, we will see what the final outcome will be”.

Therefore, it seems not unlikely that the final duration is the outcome of a political consensus between the proposal of the EU Commission and the EU Parliament following the simple equation:

However, it cannot be ruled out that the individual proposals of the respective EU institutions may have been influenced, at least in part, by the interests of various lobby groups. From a classical liberal perspective, regulation could only make economic sense if the marginal costs of the market intervention correspond to the marginal utility. From a Public Choice perspective, this is still questionable at this point, since it is assumed that politicians try to maximize their votes to stay in office and to consume the amenities of being in charge (

Downs 1957; with application to accounting,

May and Sundem 1976;

Tinker 1980;

Cooper and Sherer 1984;

Sutton 1984;

Ordelheide 1998;

Homfeldt 2013). Most of the work, however, focuses on the lobbying approach (with application to business valuation, e.g.,

Quill 2016;

Follert 2020). However, this approach does not apply to the issue under consideration. A possible explanatory approach could therefore be the self-interest axiom of political actors, which is operationalized by maximizing votes (

Schumpeter 1950;

Downs 1957). The Downsian approach can be used to analyze political action within the sphere of classical management decisions, e.g., the composition of boards (

Olbrich et al. 2016). In this respect, it is conceivable that the measures were also used to appease taxpayers after various crises.

5. Concluding Remarks and Outlook

It would be wise to limit audit tenure to 10 years if there were evidence that this is the period where audit quality reaches its maximum, i.e., that any longer audit mandate would (on average) result in audit opinions of poorer reliability. This is clearly not the case.

No matter how audit quality is defined in detail, it is out of the question that independence is one of—if not the—core element(s). Apparently, European audit regulators focus on the argument that auditors’ independence suffers from longer audit tenure—at least in public perception. In case of corporate failure where the auditor (a) was provided with a clean audit opinion and (b) was in charge for a long period, the only available explanation seems to be the impaired independence of the instance that stands for unbiased opinions and extensive expertise—the auditor. The public does (and regulators do?) not see that a 95% accuracy of audit opinion (which is the quality level required by audit standards) implicitly means that—on average—one in twenty audits fails to find all material misstatements. This phenomenon, which is well-known as the expectation gap, is immanent to standard audit procedures no matter if audit tenure is capped or not.

The fact that there is no clear evidence—neither formal nor empirical—that audit quality suffers from long audit tenures tells us that there is also no evidence that auditors’ independence in fact is corrupted by long audit tenure. From this perspective, there is no need to cap audit tenure at all—i.e., the 10-year cap is not “proven”.

Instead, EU regulators started a process to improve the public perception of the reliability of the audit outcomes, the so-called ‘independence in appearance’. They installed a maximum audit tenure of 10 years, which seems to be the result of a political process initiated by media pressure on the political authorities; however, this was apparently rather an effort at ‘pretend’ political action than installing a well-founded effective measure. In that respect, the 10-year limit is “public”, not “proven”. Moreover, due to the decentralized nature of knowledge (

Hayek 1945) and the difficulty of forecasting future events from past data, the question arises whether such a hard number can be considered useful at all, or rather whether the discovery of the optimal mandate duration is not a task for the market process (

Hayek 1969).

The aim of the present study is to emphasize that the political intervention within the European audit market is at least partially driven by other reasons than empirical evidence. This seems astonishing, as the COVID-19 crisis particularly reveals the importance of evidence-based policy. Since we could at least find indications that the 10-year period is not based on the scientific findings of international audit research, we discuss our findings in the light of Public Choice Theory and thus contribute to the New Political Economy of audit market regulation. One possible explanation could be that the choice of the 10-year period is the result of a collective decision and can be understood as a consensus between the EU institutions.

However, the informative value of our study could be limited because we have not analyzed data from certain industries and the data collection was performed manually based on the annual reports as presented on the websites of the respective companies. This results in a very low degree of coverage for some member states (e.g., <10% of the population in Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Malta), which may distort the results and should be considered in the interpretation of our findings. It is undisputed that further research is needed to make a valid judgement on the effectiveness of the regulatory measures as a whole.

While our paper provides primary and only descriptive evidence on the setting of maximum durations, to be able to make a final economic assessment of the actual effects of market intervention, further research, especially statistical analyses, e.g., based on regression analyses, are needed, in particular regarding the appropriateness of the measures and the political influence (e.g.,

Masud et al. 2019). Possible proxies for appropriateness could possibly be the measurement of audit quality and the perception of audit quality before and after regulation came into effect. Another approach could be to analyze whether the different maximum durations correlate with the individual company law of the Member State. Overall future research should build on our interdisciplinary approach between economics, politics, and law.

With our findings concerning the need for regulation of auditor tenure, we contribute to the discussion on the regulation of important sectors and the economic rationality of those political decisions, as well as the link between political decisions and empirical evidence.

This study discussed publicly available audit firm tenure data for listed companies within the European Union. The results indicate that when Regulation (EU) No. 537/2014 was agreed to in 2014 and came into effect in 2016, the average durations of audit engagements were in both cases lower than the established maximum duration for future periods.