Effect of the Great Crisis on Sectoral Female Employment in Europe: A Structural Decomposition Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Structural Decomposition Analysis

2.2. Measuring of Gender Segregation

2.3. Sources of Information

3. Results

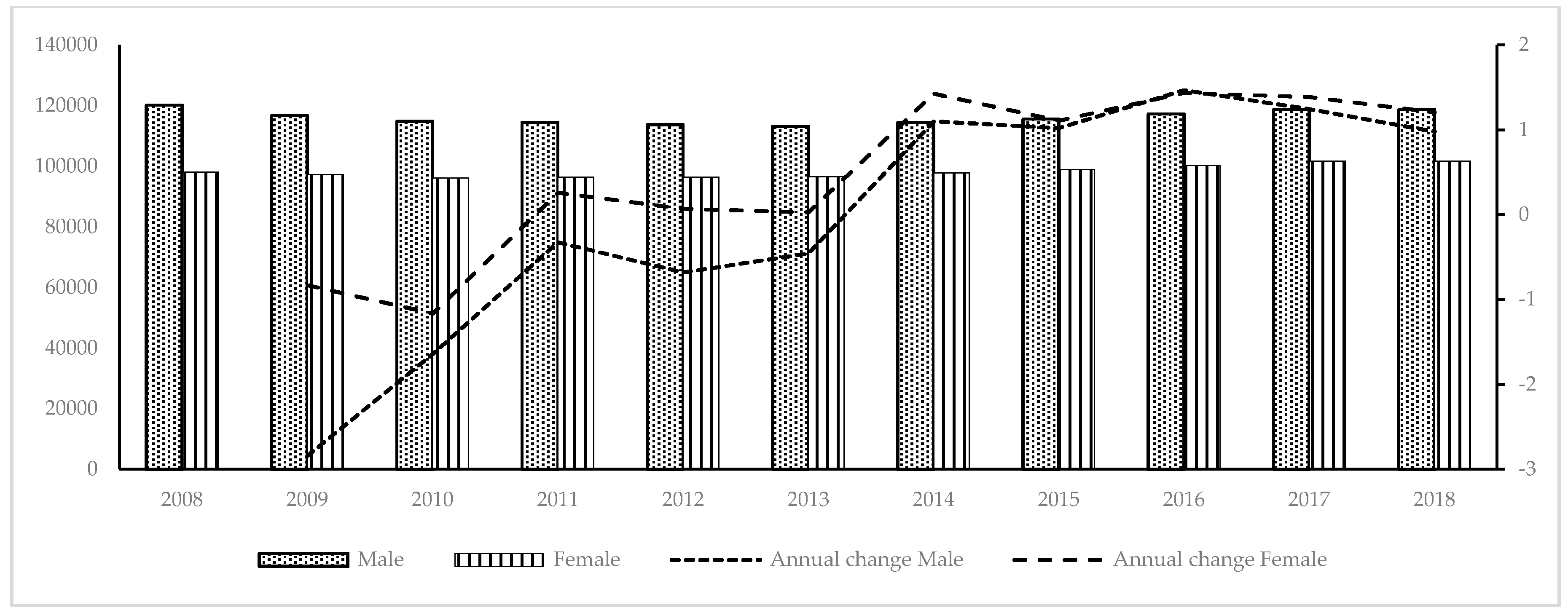

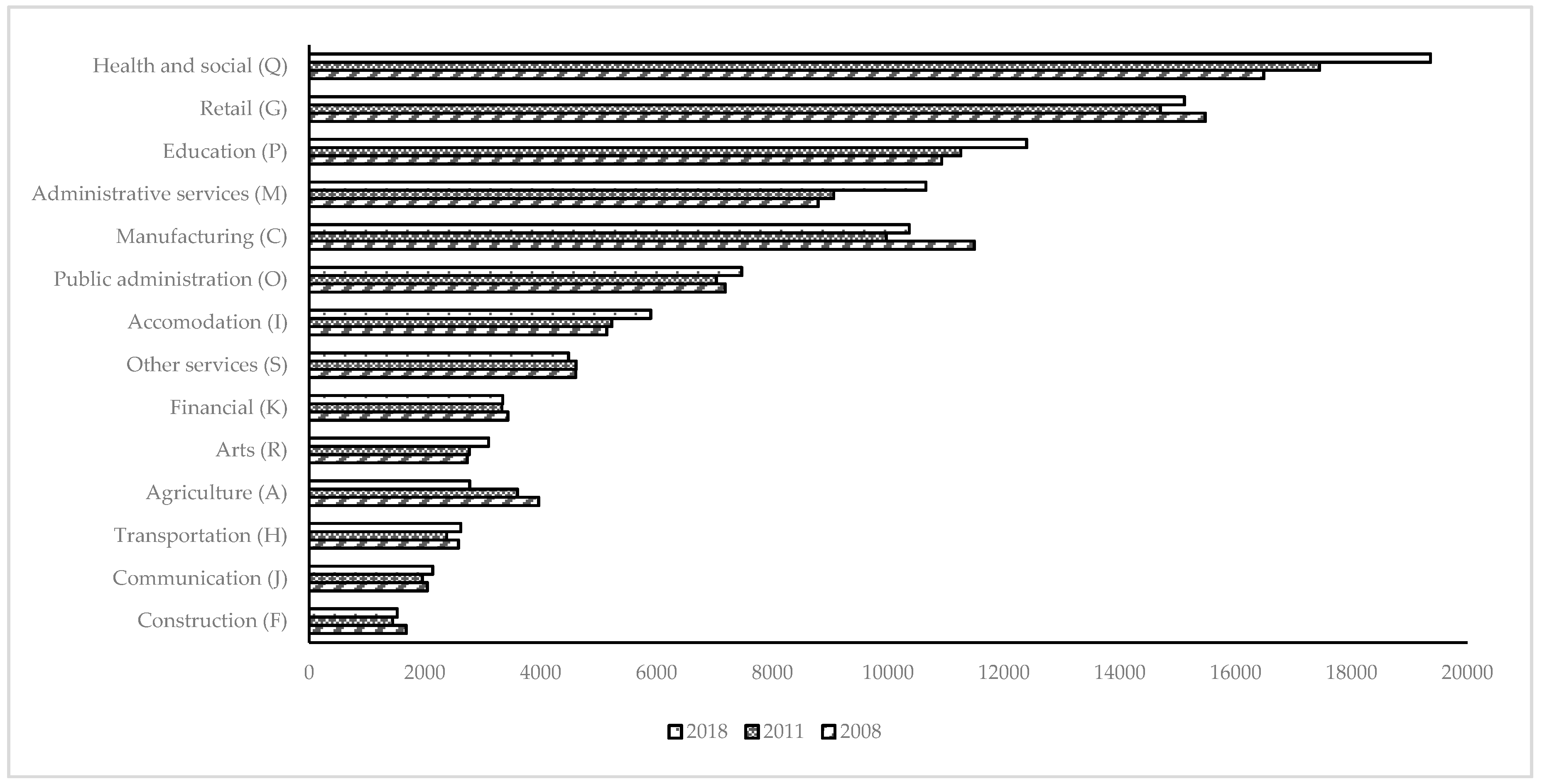

3.1. The Evolution of Female Employment and Trends in Its Sectoral Distribution

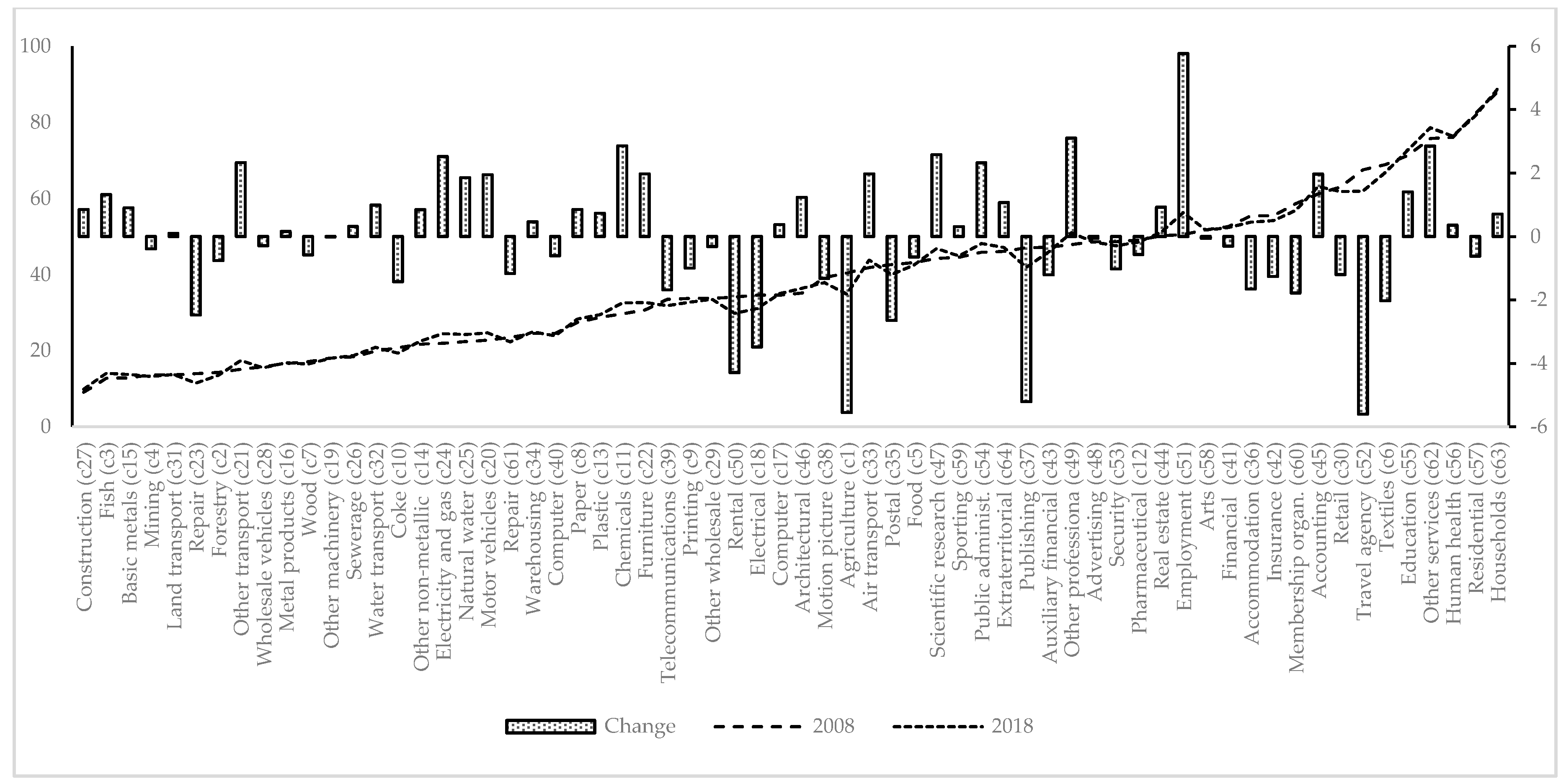

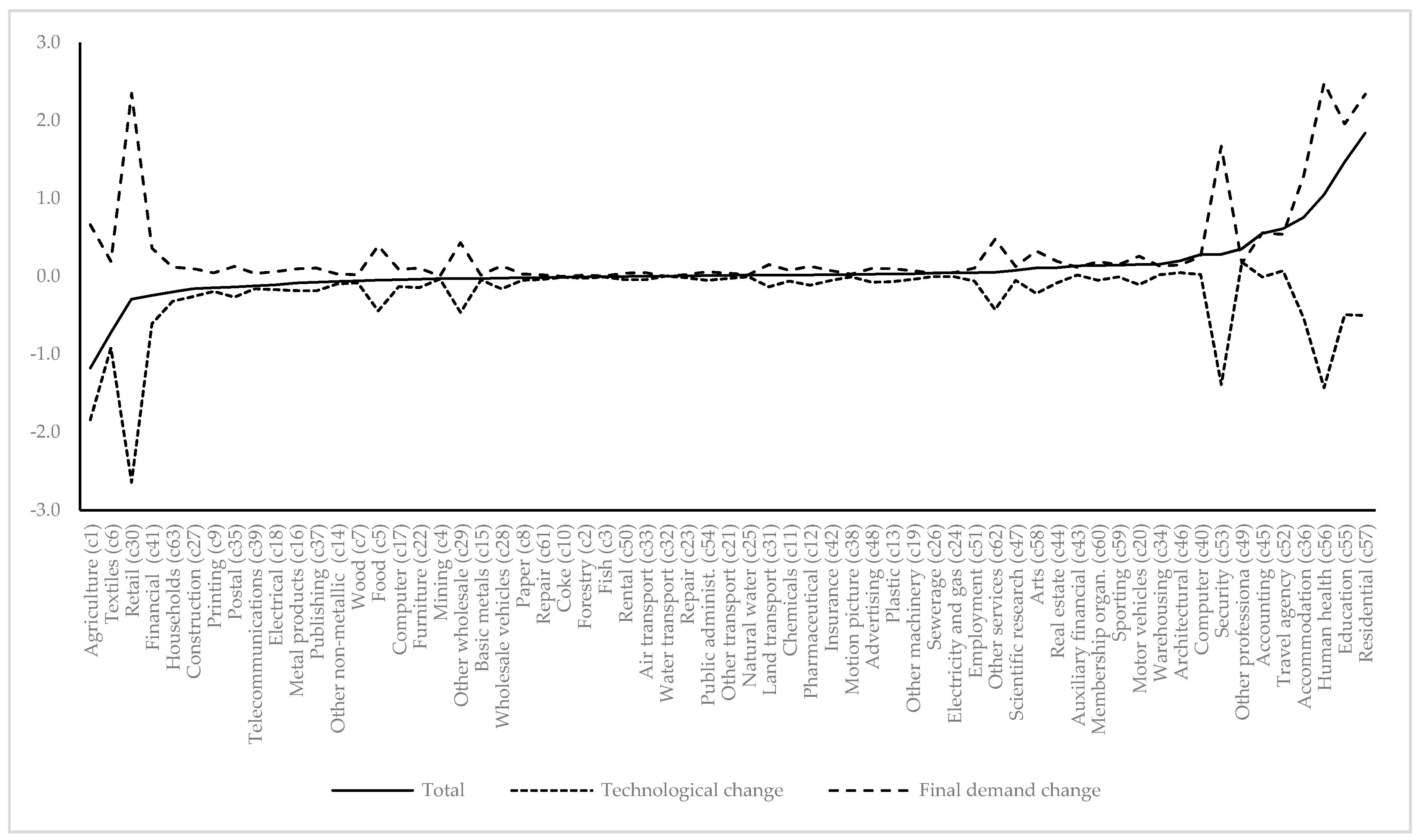

3.2. Structural Decomposition Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sectors and Codes

| Sectors | Code |

| Products of agriculture, hunting and related services | c1 |

| Products of forestry, logging and related services | c2 |

| Fish and other fishing products; aquaculture products; support services to fishing | c3 |

| Mining and quarrying | c4 |

| Food, beverages and tobacco products | c5 |

| Textiles, wearing apparel, leather and related products | c6 |

| Wood and of products of wood and cork, except furniture; articles of straw and plaiting materials | c7 |

| Paper and paper products | c8 |

| Printing and recording services | c9 |

| Coke and refined petroleum products | c10 |

| Chemicals and chemical products | c11 |

| Basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations | c12 |

| Rubber and plastic products | c13 |

| Other non-metallic mineral products | c14 |

| Basic metals | c15 |

| Fabricated metal products, except machinery and equipment | c16 |

| Computer, electronic and optical products | c17 |

| Electrical equipment | c18 |

| Machinery and equipment n.e.c. | c19 |

| Motor vehicles, trailers and semi-trailers | c20 |

| Other transport equipment | c21 |

| Furniture and other manufactured goods | c22 |

| Repair and installation services of machinery and equipment | c23 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning | c24 |

| Natural water; water treatment and supply services | c25 |

| Sewerage services; sewage sludge; waste collection, treatment and disposal services; materials recovery services; remediation services and other waste management services | c26 |

| Constructions and construction works | c27 |

| Wholesale and retail trade and repair services of motor vehicles and motorcycles | c28 |

| Wholesale trade services, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles | c29 |

| Retail trade services, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles | c30 |

| Land transport services and transport services via pipelines | c31 |

| Water transport services | c32 |

| Air transport services | c33 |

| Warehousing and support services for transportation | c34 |

| Postal and courier services | c35 |

| Accommodation and food services | c36 |

| Publishing services | c37 |

| Motion picture, video and television programme production services, sound recording and music publishing; programming and broadcasting services | c38 |

| Telecommunications services | c39 |

| Computer programming, consultancy and related services; Information services | c40 |

| Financial services, except insurance and pension funding | c41 |

| Insurance, reinsurance and pension funding services, except compulsory social security | c42 |

| Services auxiliary to financial services and insurance services | c43 |

| Real estate services excluding imputed rents | c44 |

| Legal and accounting services; services of head offices; management consultancy services | c45 |

| Architectural and engineering services; technical testing and analysis services | c46 |

| Scientific research and development services | c47 |

| Advertising and market research services | c48 |

| Other professional, scientific and technical services and veterinary services | c49 |

| Rental and leasing services | c50 |

| Employment services | c51 |

| Travel agency, tour operator and other reservation services and related services | c52 |

| Security and investigation services; services to buildings and landscape; office support and other business support services | c53 |

| Public administration and defence services; compulsory social security services | c54 |

| Education services | c55 |

| Human health services | c56 |

| Residential care services; social work services without accommodation | c57 |

| Creative, arts, entertainment, library, archive, museum, other cultural services; gambling services | c58 |

| Sporting services and amusement and recreation services | c59 |

| Services furnished by membership organisations | c60 |

| Repair services of computers and personal and household goods | c61 |

| Other personal services | c62 |

| Services of households as employers; goods and services produced by households for own use | c63 |

| Services provided by extraterritorial organisations and bodies | c64 |

References

- Adams-Prassl, Abigail, Teodora Boneva, Marta Golin, and Christopher Rauh. 2020. Inequality in the Impact of the Coronavirus Shock: Evidence from Real Time Surveys. Journal of Public Economics. in Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addabbo, Tindara, Lina Galvez Munoz, Antigone Lyberaki, Natacha Ordioni, and Paula Rodriguez Madrono. 2014. The Impacts of the Crisis on Gender Equality and Women’s Wellbeing in EU Mediterranean Countries. Turin: UNICRI United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Akbulut, Rahşan. 2011. Sectoral changes and the increase in women’s labor force participation. Macroeconomic Dynamics 15: 240–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaz Odriozola, Leire, and Begoña Eguía Peña. 2016. Segregación ocupacional por género y nacionalidad en el mercado laboral español/Gender and Nationality Based Occupational Segregation in the Spanish Labor Market. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 156: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, Titan, Matthias Doepke, Jane Olmstead-Rumsey, and Michèle Tertilt. 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality. NBER Working Paper Series 26947. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Villar, Olga, and Coral del Río. 2017a. Segregación ocupacional por razón de género y estatus migratorio en España y sus consecuencias en términos de bienestar. Ekonomiaz 91: 124–63. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Villar, Olga, and Coral del Río. 2017b. Local Segregation and Well-Being. Review of Income and Wealth 63: 269–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargawi, Hannah, Giovanni Cozzi, and Susan Himmelweit. 2017. Economics and Austerity in Europe. Gendered Impacts and Sustainable Alternatives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Belegri-Roboli, Athena, Maria Markaki, and Panayotis G. Michaelides. 2011. Labour productivity changes and working time: The case of Greece. Economic Systems Research 23: 329–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, Graziella. 2020. COVID Susceptibility Women and Work. VOX CEPR Policy Portal. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bettio, Francesca, and Alina Verashchagina. 2014. Women and men in the “Great European recession”. In Women and Austerity. The Economic Crisis and the Future for Gender Equality. Edited by Maria Karamessini and Jill Rubery. London: Routledge, pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bettio, Francesca, Marcella Corsi, Carlo D’Ippoliti, Antigone Lyberaki, Manuela Samek, and Alina Verashchagina Lodovici. 2013. The Impact of the Economic Crisis on the Situation of Women and Men and on Gender Equality Policies. Luxemburg: European Commission. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2017. The gender wage gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. Journal of Economic Literature 55: 789–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, Francine D., and Anne E. Winkler. 2018. The Economics of Women, Men, and Work. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boll, Christina, and Andreas Lagemann. 2018. Gender Pay Gap in EU Countries Based on SES (2014). Luxemburg: European Commission. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, Christina, Julian Leppin, Anja Rossen, and André Wolf. 2016. Magnitude and Impact Factors of the Gender Pay Gap in EU Countries. Luxemburg: European Commission. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, Christina, Anja Rossen, and André Wolf. 2017. The EU Gender Earnings Gap: Job Segregation and Working Time as Driving Factors. Jahrbucher Fur Nationalokonomie Und Statistik 237: 407–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrowman, Mary, and Stephan Klasen. 2020. Drivers of Gendered Sectoral and Occupational Segregation in Developing Countries. Feminist Economics 26: 62–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraway, Teri L. 2006. Gendered paths of industrialization: A cross-regional comparative analysis. Studies in Comparative International Development 41: 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascal, André. 2017. Drivers of change in the European youth employment: A comparative structural decomposition analysis. Economic Systems Research 29: 463–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, Inmaculada, and Gloria Moreno. 2018. Desigualdades de género en el mercado laboral. Panorama Social 27: 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry, Misbah T., and Paul Elhorst. 2018. Female labour force participation and economic development Article information. International Journal of Manpower 39: 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, Rachel, and Ebru Kongar. 2017. Feminist Approaches to Time Use. In Gender and Time Use in a Global Context. The Economics of Employment and Unpaid Labor. Edited by Rachel Conenlly and Ebru Kongar. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Danchev, Svetoslav, Grigoris Pavlou, and Ilias Kostarakos. 2014. Input-Output Analysis of Sectoral Labor Dynamism. In The Rebirth of the Greek Labor Market. Building Toward 2020 After the Global Financial Meltdown. Edited by Panagiotis E. Petrakis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 153–80. [Google Scholar]

- De Henau, Jerome, and Susan Himmelweit. 2020. Stimulating OECD Economies Post-Covid by Investing in Care. IKD Working Paper 85. Milton Keynes: The Open University, Innovation, Knowledge and Development Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Dietzenbacher, Erik, and Bart Los. 1998. Structural Decomposition Techniques: Sense and Sensitivity. Economic Systems Research 10: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, Rosa, Cristina Sarasa, and Mónica Serrano. 2019. Structural change and female participation in recent economic growth: A multisectoral analysis for the Spanish economy. Economic Systems Research 31: 574–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Otis D., and Beverly Duncan. 1955. A Methodological Analysis of Segregation Indexes. American Sociological Review 20: 210–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2017. EU Action Plan 2017–2019 Tackling the Gender Pay Gap. COM(2017) 678 Final. Luxemburg: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2019. Report on Equality between Women and Men in the European Union. Luxemburg: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. 2013. Council Regulation (EC) No 549/2013 on the European System of National and Regional Accounts in the European Union (ESA 2010). Brussels: European Council. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. 2019a. Symmetric Input-Output Table at Basic Prices. Eurostat Home. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=naio_10_cp1700&lang=en (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Eurostat. 2019b. Employment by Sex, Age and Detailed ECONOMIC activity. Eurostat Home. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfsq_egan22d&lang=en (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Forssell, Osmo. 1990. The input-output framework for analysing changes in the use of labour by education levels. Economic Systems Research 2: 363–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddis, Isis, and Stephan Klasen. 2014. Economic development, structural change, and women’s labor force participation: A reexamination of the feminization U hypothesis. Journal of Population Economics 27: 639–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez Muñoz, Lina, and Paula Rodríguez-Modroño. 2017. Crisis, austeridad y transformaciones en las desigualdades de género. Ekonomiaz 91: 330–59. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, Claudia. 1994. The U-shaped female labour force function in economic development and economic history. NBER Working Paper Series 4707: 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, Claudia. 2014. A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter. American Economic Review 104: 1091–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, Mary, Ben Zissimos, and Christine Greenhalgh. 2001. Jobs for the skilled: How technology, trade and domestic demand changed the structure of UK employment, 1979–90. Oxford Economic Papers 53: 20–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunluk-Senesen, Gulay, and Umit Senesen. 2011. Decomposition of labour demand by employer sectors and gender: Findings for major exporting sectors in Turkey. Economic Systems Research 23: 233–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegewisch, Ariane, and Heidi Liepmann. 2014. Occupational Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap: A Job Half Done. Washington, DC: Institute for Women´s Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Hegewisch, Ariane, Heidi Liepman, Jeff Hayes, and Heidi Hartman. 2010. Separate and Unequal: Occupation-Establishment Sex Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap. Washington, DC: Institute for Women´s Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Humpert, Sthephan. 2015. Gender-based Segregation before and after the Great Recession. Theoretical Applied Economics 22: 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hupkau, Claudia, and Barbara Petrongolo. 2020. Work, care and gender during the Covid-19 crisis. In CEP Covid-19 Analysis. Paper No. 002. London: London School of Economics and Political Science. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2016. Women at Work: Trends 2016. Geneva: International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminioti, Olympia. 2014. The Labor Dynamism of the Sectors of Economic Activity. In The Rebirth of Greel Labor Markets. Building Toward 2020 after the Global Financial Meltdown. Edited by Panagiotis E. Petrakis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 127–52. [Google Scholar]

- Karamessini, Maria, and Jill Rubery. 2014a. Economic crisis and austerity. Challenges to gender equality. In Women and Austerity. The Economic Crisis and the Future for Gender Equality. Edited by Maria Karamessini and Jill Rubery. London: Routledge, pp. 314–51. [Google Scholar]

- Karamessini, Maria, and Jill Rubery. 2014b. The Challenge of Austerity For Equality. Revue de l’OFCE 133: 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamessini, Maria, and Jill Rubery. 2017. The Challenge of Austerity for Gender Equality in Europe: A Consideration of Eight Countries at the Center of the Crisis. In Gender and Time Use in a Global Context. Edited by Rachel Connelly and Ebru Kongar. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 51–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kijong, Ipek Ilkkaracan, and Tolga Kaya. 2019. Public investment in care services in Turkey: Promoting employment & gender inclusive growth. Journal of Policy Modeling 41: 1210–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucera, David, and Sheba Tejani. 2014. Feminization, defeminization, and structural change in manufacturing. World Development 64: 569–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, Astrid. 2018. The gender wage gap in developed countries. In The Oxford Handbook of Women and The Economy. Edited by Susab L. Averett, Laura M. Argys and Saul D. Hoffman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 369–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kushi, Sidita, and Ian P. McManus. 2018. Gendered Costs of Austerity: The Effects of the Great Recession and Government Policies on Employment across the OECD. International Labour Review 157: 557–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechman, Ewa, and Harleen Kaur. 2015. Economic growth and female labor force participation –verifying the U-feminization hypothesis. New evidence for 162 countries over the period 1990–2012. Economics and Sociology 8: 246–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontief, Wassily. 1974. Structure of the World Economy: Outline of a Simple Input-Output Formulation. American Economic Review 64: 823–34. [Google Scholar]

- Madariaga, Rafa. 2018. Factors driving sectoral and occupational employment changes during the Spanish boom (1995–2005). Economic Systems Research 30: 400–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magacho, Guilherme R., John S. L. McCombie, and Joaquim J. M. Guilhoto. 2018. Impacts of trade liberalization on countries’ sectoral structure of production and trade: A structural decomposition analysis. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 46: 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, Friederike. 2011. Will the crisis change gender relations in labour markets and society? Journal of Contemporary European Studies 19: 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Tola, Elena, María L. De la Cal, and Irantzu Álvarez-González. 2018. Crisis and austerity: Threat for women´s employment in the European regions. Convergentia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 77: 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruani, Margaret. 2000. De la Sociología del trabajo a la Sociología del empleo. Política y Sociedad 34: 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Ronald E., and Peter D. Blair. 2009. Input–Output Analysis. Foundations and Extensions, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moir, Hazel, and Joy S. Smith. 1979. Industrial segregation in the Australian Labour Market. The Journal of Industrial Relations 21: 281–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2012. Closing the Gender Gap. Act Now. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2017. The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, Amado, Jorge Belaire-Franch, and María T. Gonzalo. 2012. Unemployment, cycle and gender. Journal of Macroeconomics 34: 1167–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Boquete, Yolanda, Sergio De Stefanis, and Manuel Fernández-Grela. 2010. The distribution of the gender wage discrimination in Italy and Spain: A comparison using the ECHP. International Journal of Manpower 31: 109–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Orozco, Amaia. 2005. Economía del género y economía feminista ¿conciliación o ruptura? Revista Venezolana de Estudios de La Mujer 10: 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Périvier, Hélène. 2014. Men and Women during the Economic Crisis. Employment Trends in Eight European Countries. Revue de l’OECD 133: 41–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Périvier, Hélène. 2018. Recession, austerity and gender: A comparison of eight European labour markets. International Labour Review 157: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, Cristiano, Jelena Žarković Rakić, and Marko Vladisavljević. 2019. Austerity and gender inequalities in Europe in times of crisis. Cambridge Journal of Economics 43: 733–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzu, Giovanni, and Carl Singleton. 2016. Gender and the business cycle: An analysis of labour markets in the US and UK. Journal of Macroeconomics 47: 131–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzu, Giovanni, and Carl Singleton. 2018. Segregation and Gender Gaps in the United Kingdom’s Great Recession and Recovery. Feminist Economics 24: 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Adam, and Sthephen Casler. 1996. Input-Output structural analysis decomposition: A critical appraisal. Economic System Research 8: 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Adam, and Chia-Yon Chen. 1991. Sources of change in energy use in the U.S. economy, 1972–1982. A structural decomposition analysis. Resources and Energy 13: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubery, Jill. 1988. Women and Recession. London: Routledge. New York: Kegal Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Rubery, Jill. 2015. Austerity and the future for gender equality in Europe. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 68: 715–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubery, Jill, and Gail Hebson. 2018. Applying a gender lens to employment relations: Revitalisation, resistance and risks. Journal of Industrial Relations 60: 414–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubery, Jill, and Anthony Rafferty. 2013. Women and recession revisited. Work, Employment and Society 27: 414–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda-Cantuche, José M., and Nuno Sousa. 2017. Are EU Exports Gender-Blind? Some Key Features of Women Participation in Exporting Activities in the EU. TRADE Chief Economist Note, No. 3. Brussels: European Union, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Salgueiro, Fernando, Suzana Quinet de Andrade, and Marcilio Zanelli. 2016. Decomposição Estrutural Do Emprego E Da Renda No Brasil: Uma Análise De Insumo-Produto—1990 a 2007. Nova Economia 26: 909–42. [Google Scholar]

- Saraçoğlu, Dürdane Ş., Emel Memiş, Ebru Voyvoda, and Burça Kızılırmak. 2018. Changes in Global Trade Patterns and Women’s Employment in Manufacturing, 1995–2011. Feminist Economics 24: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, Axel. 2007. Women’s and men’s contributions to satisfying consumers’ needs: A combined time use and input-output analysis. Economic Systems Research 19: 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, Axel. 2008. Gender-Specific Input-Output Analysis. Interdisciplinary Information Sciences 14: 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scicchitano, Sergio. 2012. The male–female pay gap across the managerial workforce in the United Kingdom: A semi-parametric decomposition approach. Applied Economics Letters 19: 1293–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scicchitano, Sergio. 2014. The gender wage gap among Spanish managers. International Journal of Manpower 35: 327–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, Almudena, and Sarah Smith. 2020. Baby Steps: The Gender Division of Childcare after COVID19. Discussion Paper Series No. 13302. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Simas, Moana S., and Richard Wood. 2018. The distribution of labour and wages embodied in European consumption. In The Social Effects of Global Trade Quantifying Impacts Using Multi-Regional Input-Output Analysis. Edited by Joy Murray, Arunima Malik and Arne Geschke. Singapore: Taylor & Francis, pp. 103–16. [Google Scholar]

- Simas, Moana S., Laura Golsteijn, Mark A. J. Huijbregts, Richard Wood, and Edgar G. Hertwich. 2014. The “bad labor” footprint: Quantifying the social impacts of globalization. Sustainability 6: 7514–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, Isabelle, Steven Stillman, and Richard Fabling. 2017. What Drives the Gender Wage Gap? Examining the Roles of Sorting, Productivity Differences, and Discrimination. Motu Working Paper 17-15. Motu Economic and Public Policy Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolka, Jiří. 1989. Input-Output Structural Decomposition Analysis for Austria. Journal of Policy Modelling 11: 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, Stephanie. 2012. The Contextual Challenges of Occupational Sex Segregation: Deciphering Cross-National Differences in Europe. Berlin: VS Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason, Bobbi, and Inmaculada Macias-Alonso. 2020. COVID-19 and raising the value of care. Gender, Work & Organization, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Tin, Poo B. 2014. A decomposition analysis for labour demand: Evidence from Malaysian manufacturing sector. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics 11: 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tonoyan, Vartuhi, Robert Strohmeyer, and Jennifer E. Jennings. 2020. Gender Gaps in Perceived Start-up Ease: Implications of Sex-based Labor Market Segregation for Entrepreneurship across 22 European Countries. Administrative Science Quarterly 65: 181–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2017. El empoderamiento económico de la mujer en el cambiante mundo del trabajo. E/CN.6/2017/3. Vol. E/CN.6/201. Consejo Económico y Social. Naciones Unidas. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Woetzel, Jonathan, Anu Madgavkar, Kweilin Ellingrud, Eric Labaye, Sandrine Devillard, Eric Kutcher, James Manyika, Richard Dobbs, and Mekala Krishnan. 2015. The Power of Parity: How Advancing Women’s Equality Can Add $12 Trillion to Global Growth. London: McKinsey Global Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Yurtoglu, B. Burcin, and Christine Zulehner. 2009. Sticky Floors and Glass Ceilings in Top Corporate Jobs. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1470860 (accessed on 3 August 2020).

| 1 | |

| 2 | The protective effect of gender segregation on female employment in less cyclical sectors had also been identified in previous recessions (Rubery 1988; Rubery and Rafferty 2013). |

| 3 | Other decompositions, based on shift-share analysis, can be found in the literature, but they consider only two components: the demographic effect and the participation effect (Rubery 1988; Périvier 2014; Rubery and Rafferty 2013). |

| 4 | This is to evaluate changes in male and female employment, and thus compute the respective sectoral segregation indexes. In the results section, however, the exposition and analysis consider changes only in female employment. |

| 5 | In this structural decomposition method, changes in input-output coefficients are interpreted as technological change, that is, changes that do not necessarily impact on total technological growth, in the Solow sense of the term (Magacho et al. 2018). These changes are interpreted as any factor that can cause a change in the technical coefficient, such as technological change, technical substitution and scale effects (Rose and Casler 1996). |

| 6 | During the recovery stage of previous recessions, annual growth rates were higher for male than for female employment (Maier 2011). |

| 7 | In some countries, the female share in total employment has grown as some housework has been externalized through public services, but most of the jobs are in the care sector (Périvier 2018). This has been a key contributing factor to the gender segregation of labor markets. |

| 8 | The interaction effects are ignored because, based on this average, they are almost null. |

| 9 | This is a common finding in SDA applications analyzing employment change, which is why authors focus their analyses mainly on the other components (Madariaga 2018). |

| Component | Thousands of Jobs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial indices of sectoral gender segregation | 21.01 | 0.1382 | |

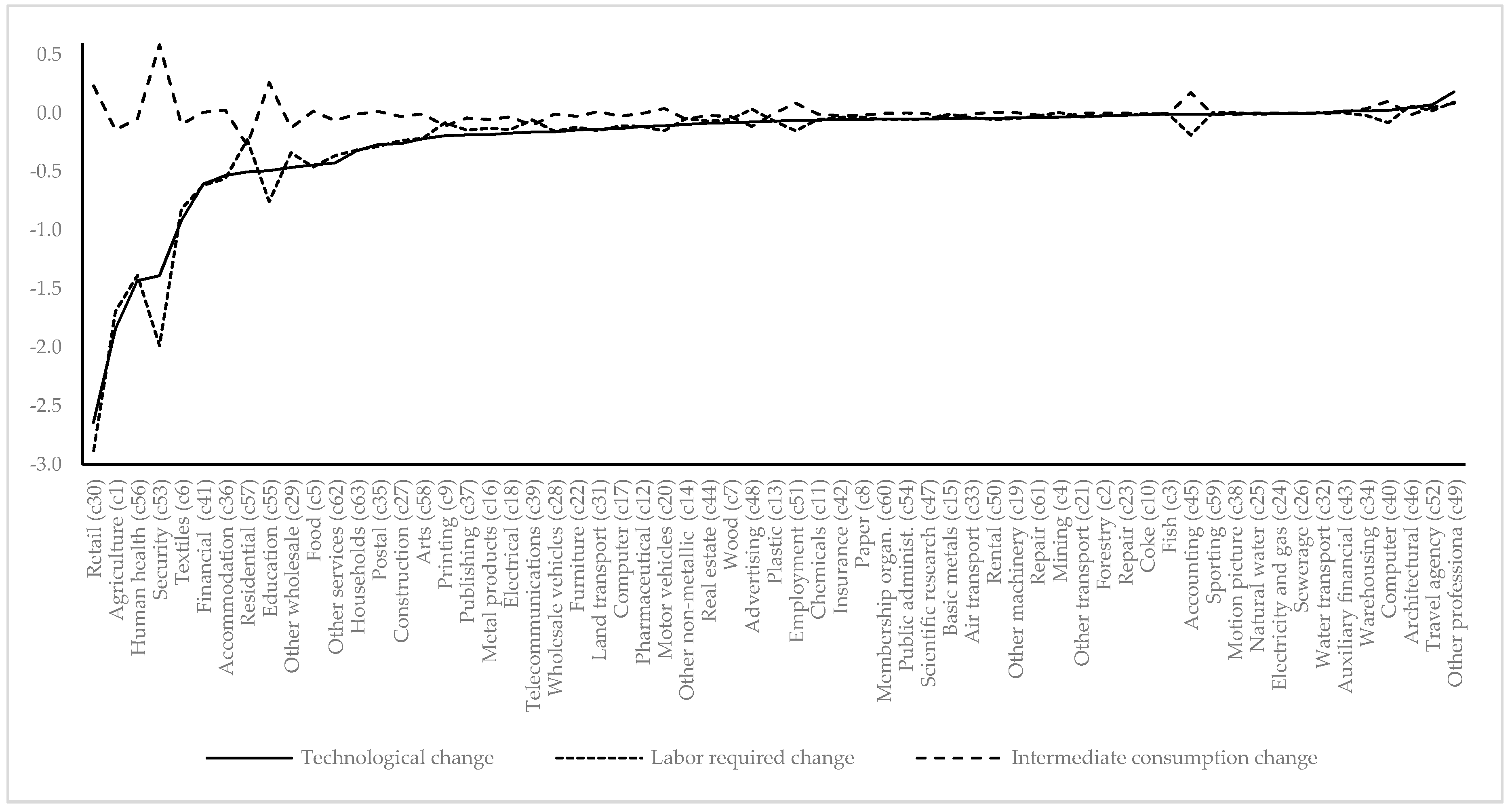

| Technological change | −15,182.9 | 20.91 | 0.1345 |

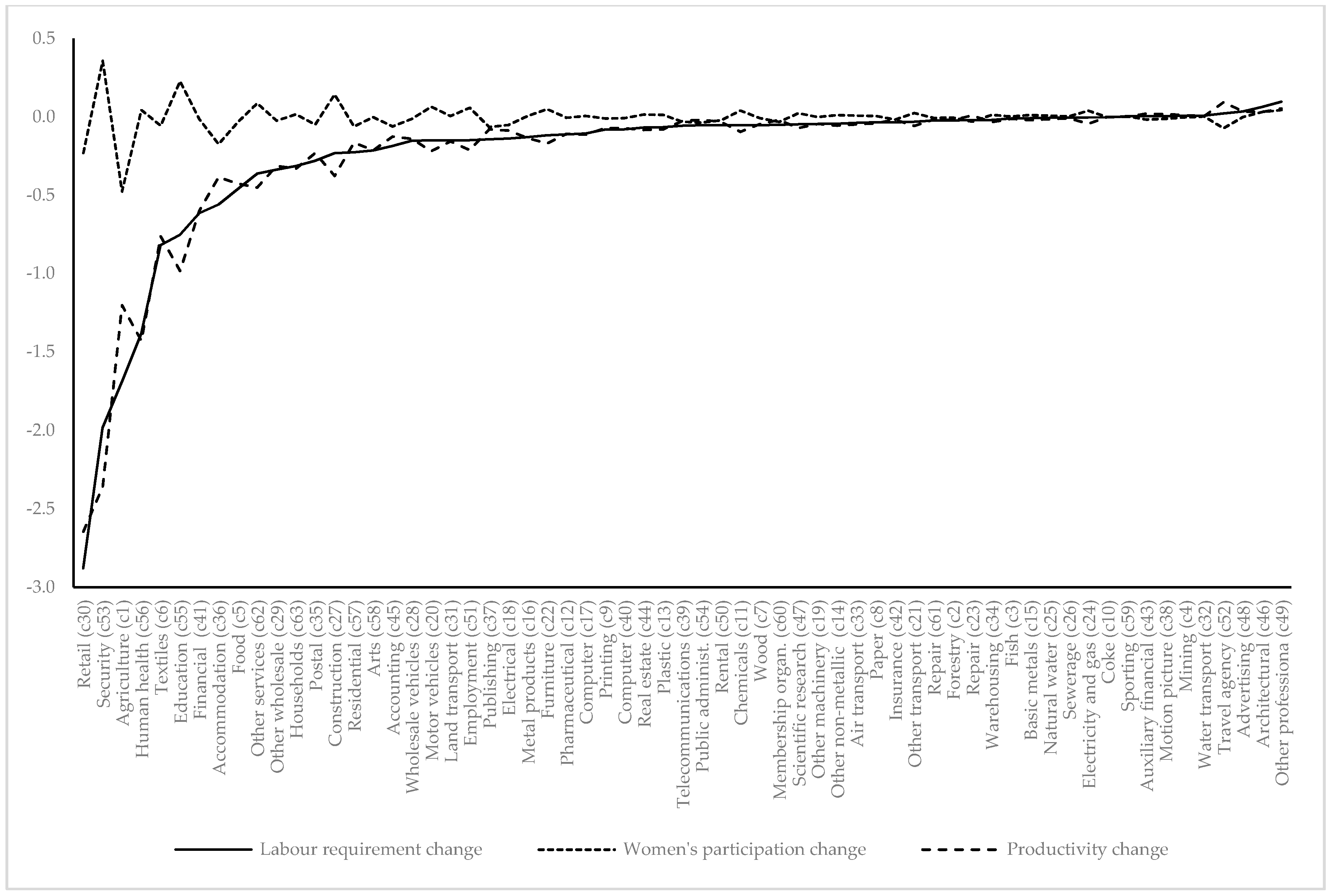

| Labor requirement change | −15,402.0 | 21.27 | 0.1398 |

| Change in women’s labor participation | −239.8 | 21.26 | 0.1390 |

| Productivity change | −15,169.6 | 20.97 | 0.1381 |

| Intermediate consumption change | 223.8 | 20.71 | 0.1361 |

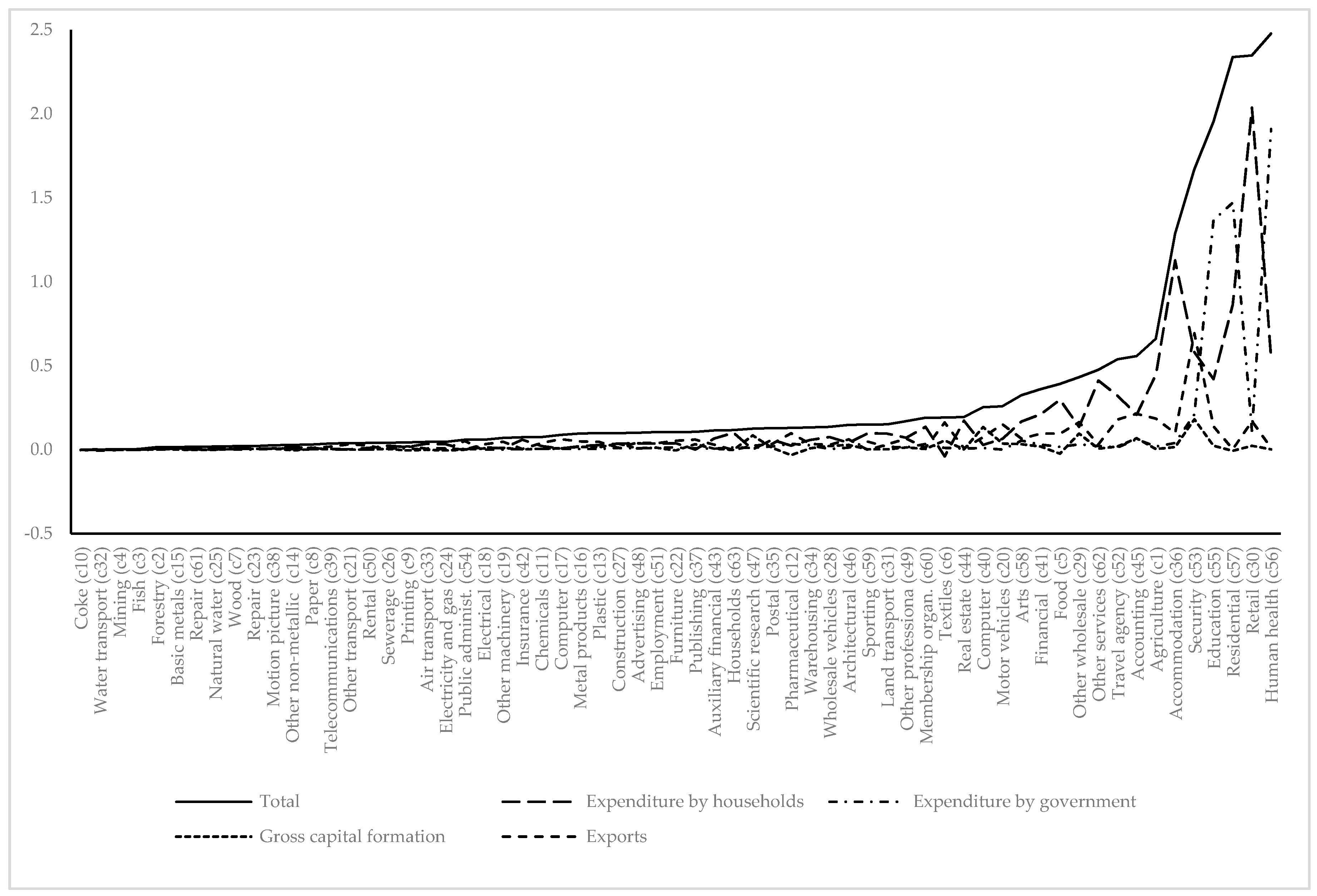

| Final demand change | 20,087.5 | 20.47 | 0.1328 |

| Expenditure by households | 9434.8 | 20.56 | 0.1342 |

| Expenditure by government | 5884.8 | 20.85 | 0.1371 |

| Gross capital formation | 1087.5 | 21.09 | 0.1391 |

| Exports | 3680.4 | 20.91 | 0.1371 |

| Total change/final indices | 4904.6 | 20.27 | 0.1272 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barba, I.; Iraizoz, B. Effect of the Great Crisis on Sectoral Female Employment in Europe: A Structural Decomposition Analysis. Economies 2020, 8, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8030064

Barba I, Iraizoz B. Effect of the Great Crisis on Sectoral Female Employment in Europe: A Structural Decomposition Analysis. Economies. 2020; 8(3):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8030064

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarba, Izaskun, and Belen Iraizoz. 2020. "Effect of the Great Crisis on Sectoral Female Employment in Europe: A Structural Decomposition Analysis" Economies 8, no. 3: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8030064

APA StyleBarba, I., & Iraizoz, B. (2020). Effect of the Great Crisis on Sectoral Female Employment in Europe: A Structural Decomposition Analysis. Economies, 8(3), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8030064