Abstract

Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) contribute to the economic development of most developing countries. However, the economic performance of the MSMEs is often restricted by several obstacles. This paper reports on a study of the impacts of public sector corruption on employment growth in MSMEs, as perceived by their managers/owners. The data originated from a nationwide survey that involved MSMEs managers/owners in Papua New Guinea (PNG) that were selected by a stratified random sampling technic. The data was analyzed using a two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression model. The results show that MSME managers/owners perceive that corruption in the public sector is generally linked to an increase in employment growth in their firms. Medium-size enterprises benefit most from corruption in the public sector, whereas small-size firms appear not to benefit. The findings indicate that other than corruption, there might be failures in the public institutions that are hampering the competitiveness, innovations and efficiency in MSMEs. Corrupt practices can precipitate the loss of revenue that would have accrued to the government from tax that could be used to provide facilities required by the public institutions. Corruption in the public institutions of developing countries such as PNG can be tackled by implementing strategies that promote zero-tolerance for corruption. These include promoting public awareness of the cost of corruption to the country’s economy, improvement in the quality of governance, and expanding the capacity of government agencies for effective and efficient service delivery. Increasing the penalty for engaging in corrupt practices could also be considered, while people who engage in practices that discourage corruption should be rewarded. The findings contribute to a potential strategy that could be used to promote ease of doing business in a country by considering the obstacles that MSMEs face.

JEL Classification:

C26; D73; H26; M14; M38

1. Introduction

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) often form the largest segment of the private sector and are important drivers of economic development in most developing countries (van den Berg and Noorderhaven 2016). However, corruption associated with the public sector is often perceived as one of the biggest threats to the SMEs in these countries (Hardoon and Heinrich 2013). Corruption, i.e., the abuse of public office for private gain (Abed and Gupta 2002) can be classified into three types. This include rule-bending, i.e., providing the briber preferential treatment by a public office holder (van den Berg and Noorderhaven 2016). Rule-breaking, i.e., extortion of money by public office holder (Begovic 2005) and state-capture, i.e., the changing of existing rules and regulations to favor the corruptor’s interests (van den Berg and Noorderhaven 2016). Corruption is often seen as an impediment to economic growth, which restricts economic development. It reduces potential investors’ willingness to invest and restricts direct foreign investment (Shleifer and Vishny 1993). However, some authors have argued that corruption has the potential of functioning as ‘speed money’ by enabling investors to avoid bureaucratic delay (Leff 1964). In order to better understand corruption, it is necessary to have knowledge associated with the corruptor’s perspectives, and this study contributes to an understanding of this aspect of corruption. Though corruption has effects on a country’s economy, it is important to note that it arises from the summation of myriads of interactions at both the micro and macro levels. Furthermore, the costs and benefits associated with corruption emanate from the interactions between different economic agents such as SME managers and certain government officials. Thus, for us to understand the principles associated with corruption, it is necessary to start from the firm level. However, only a few studies such as van den Berg and Noorderhaven (2016) and Williams and Martinez-Perez (2016) have focused on corruption at the firm level. This study attempts to fill the literature gap by examining the impact of corruption on employment in micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Papua New Guinea (PNG).

Corruption is often perceived as a complex phenomenon that can be fully understood by taking social context into account (van den Berg and Noorderhaven 2016). However, in PNG, corrupt practices are perceived differently. Some people perceive it as being connected to the State, while others are worried about corruption that involves non-state actors, as well as cultural decay (Walton 2015). Corruption in PNG is regarded as a governance issue which is strongly linked to the failure of institutions (Gbetnkom 2017). As in most developing countries, corruption is a concern for MSMEs in PNG. In survey of SMEs in PNG by Tebbutt Research (2014), it was found that from a list of 27 possible obstacles that government corruption is one of the most serious impediments to doing business in the country.

MSMEs provide jobs for many people and contribute to PNG’s economy. However, little is known about the effect of corruption on private sector businesses in PNG. In this study, we explore the impacts of corruption on the economic performance of MSMEs in 22 provinces of the country using data collected by Tebbutt Research (2014). As the perception that corruption is bad for business is not widely supported in the literature (e.g., Wang and You 2012), it is important to explore the perceptions of corruption by business owners and managers in PNG.

The findings from this study have the potential to provide us with more understanding on the nature and the magnitude of corruption linked to MSMEs in PNG.

There are various indicators that can be used to measure firm growth. These include growth rates of firm sales income (Wang and You 2012), growth rates of firm profits (Sharma and Mistra 2015), employment growth (Williams and Martinez-Perez 2016), investment (De Waldemar 2012), and firm efficiency (Hanousek et al. 2017). In this study, we have used employment growth as a measure of firm growth. This is because it is easier for firms to manipulate figures associated with growth measures, except for firm efficiency and employment growth. However, as records associated with output are often poorly kept by MSMEs in PNG, it was difficult for us to use firm efficiency as a growth measure. As an alternative to firm efficiency, we have used employment growth as a measure of firm growth. Employment growth is defined as the change in percentage from one year to another of the total number of employed persons in a firm being studied. There are only a few published articles on the impacts of corruption on firm growth that have focused on employment growth in developing countries (e.g., Williams and Martinez-Perez 2016). This study differs from that of Williams and Martinez-Perez (2016) because, apart from the impact of corruption on employment growth, we have also explored the impact in relation to firm size.

Most of the published articles that have found a link between corruption and economic performance have focused on the national level, which can make it difficult to understand the impact of corruption on the various sectors of the economy. In this study, we have focused on the firm level, specifically MSMEs. Findings from our study have the potential to contribute to SME policies and help address issues associated with the corruption that SME owners and managers face in doing business, as the amount paid in bribes by corruptors is often linked to how much a firm can afford. It will also assist us in identifying the type and size of firms that are likely to be most affected by corruption. This has the potential to provide policy makers and planners with better understanding of intervention strategies that could be used to tackle corruption associated with different types of firms.

The objectives of this study are to examine MSME managers’ perceptions of the impact of public sector corruption on employment growth of their enterprises and how the growth relates to firm size, while controlling for other firm performance determinants. It is also to identify potential corruption mitigation strategy that can be used to address issues associated with corruption in the public sector.

Findings from this study will provide policy makers and planners with a better understanding of potential strategies that can be used to tackle corruption obstacles that restrict MSMEs from contributing their full potential to the economy. This has the potential to contribute to the national SME policy by considering the effects of corruption on firm performance.

2. Conceptual Framework

Societies often have established laws and regulations and formal institutions that provide the legal rules of the game (Williams and Horodnic 2015). However, societies also have unwritten shared rules that are created and enforced outside the officially accepted channels as an informal institution (Helmke and Levitsky 2004). Corruption emanates from the failures of the formal institution and asymmetry between formal and informal institutions, such as the inefficiency or resource misallocations by the formal institution (Qian and Strahan 2007). It can also arise when a formal institution is used to protect or maximize economic rent for the elites (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012). The incongruence between what is perceived as legitimate by the formal and informal institutions has the potential to trigger corruption in a society (Williams and Shahid 2016). However, the impacts of corrupt practices on firm performance has been inconclusive.

PNG is a typical developing country that consists of a mixture of formal and informal institutions with the potential to generate corrupt practices (Woolford 1976). The MSMEs are the source of employment and livelihoods for many people, as well as revenue through tax for the PNG government. Activities that might restrict the proper functioning of the MSMEs might have adverse effects on the livelihood of these people and revenue for the government. Because MSMEs in PNG often need the services of government officials for different activities, such as registration of a firm, taxation and contracts, this can provide opportunities for corrupt practices. In order to explore the impact of corruption practices on the economic performance of MSMEs in PNG, this study has focused on the influence of corruption on employment growth associated with MSMEs.

MSME managers’ preferences concerning different states of the world reflect the utility (benefits) and disutility (costs) associated with those states (Ezebilo 2011). In decisions that may have impacts on the performance of a MSME, the manager often considers the potential benefits and the associated costs in accordance with prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). They tend to have positive assessments of activities that increase performance of the MSME and negative assessments of activities that degrade the performance. Their beliefs determine their attitudes and behavior in relation to MSME management decisions (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). The manager’s decision concerning whether to engage in corrupt practices to enhance the performance of the MSME will depend on the utility they get from the practices. The manager will engage in corrupt practices if the expected benefits from the practices are greater than the costs associated with being caught and the severity of the sanctions (Choi 2009), as follows:

where U0 is the expected benefits (utility) associated with engaging in corrupt practices without being caught and U1 is the utility from not engaging in the practices. Thus, if engaging in corruption results in a greater performance for the MSME than not engaging in it, it provides the manager with the economic incentive to choose the former. If the manager chooses to engage in corruption, her/his utility will depend on an attribute vector that characterizes the MSME as:

where f(x) is the function of the MSME attributes. It follows that the manager’s assessment of corrupt practices in relation to performance (in this case, employment growth) will depend on the number of additional people who will be employed as a result of engaging in corrupt practices and attributes of the MSME:

U0 > U1

U0 = f(x)

growth = C + f(x) + ε

2.1. Corrupt Practices Will Result in a Decrease in Firm Growth

In an Indian study of the impact of bribe payment on firms’ performance, Sharma and Mitra (2015) found that bribe payments diminish profitability and technical efficiency. In a Ugandan study, Fisman and Svensson (2007) found that bribery decreases firm growth. An Indian study on the impact of corruption on the introduction of new products found that corruption diminishes the probability of new products being introduced (De Waldemar 2012). In a study of firm efficiency in corrupt environments, Hanousek et al. (2017) found that environment characterized by a high level of corruption in Central and Eastern European countries had an adverse effect on firm efficiency. In a Greek study on the effect of corruption on firm performance, , Athanasouli et al. (2012) found that Greek firms that engage in corruption have a lower level of performance. In a study of corruption, bureaucracy and firm productivity in Africa, Faruq et al. (2013) found that less productive firms are likely to engage in bribery.

Kenny (2007) found that corruption results in the construction of poor-quality infrastructure by the construction industry in developing countries, Tanzi and Davoodi (2000) found that large firms are less vulnerable to impacts of corruption than smaller firms because they often have skills to bypass government regulations and tax laws. The World Bank (2018) found that corruption has a negative impact on firms’ growth of sales in China. In an assessment of the effects of corruption and crime on firm performance in Latin America, Gaviria (2002) found that firms that engage in payments to corrupt public officials had stunted sales growth. In a study of the effect of corruption on firms’ investment growth in Latin America, Asiedu and Freeman (2009) found that corruption adversely affect firms’ investment patterns. In a Mauritanian study of firms’ ability to do business in that country, Francisco and Pontara (2007) found that bribery places huge burdens on firms because it weakens their ability to grow.

2.2. Corrupt Practices Will Result in an Increase in Firm Growth

Only a few authors have found that corruption is associated with an increase in firms’ growth. For example, Wang and You (2012) found in a Chinese study on the influence of corruption on firm growth that corruption increases sales income for both state-owned and privately-owned firms. In a study of the impacts of corruption on firm performance in 132 developing countries, Williams and Martinez-Perez (2016) found that corruption results in an increase in firm sales and productivity. Ayaydin and Hayaloglu (2014) found in a Turkish study on the relationship between corruption and growth of manufacturing firms that making payments to public officials increases growth because it helps to reduce bureaucratic delays. Vial and Hanoteau (2010) found that corruption is associated with an increase in firm output and productivity. Blagojevic and Damijan (2012) found that private firms that are involved in making corrupt payments to public officials have higher productivity than firms that do not make payments.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. The Data Used in This Study

The data originated from structured interviews of SMEs that was conducted by Tebbutt Research (2014) from October to December 2013. The survey involved a sample of formal SMEs operating in selected urban, rural and remote locations in each of the 22 provinces of the four regions of PNG. Random sampling technique was used to select SMEs in selected business districts in urban, rural and remote locations. Owners and/or managers of 1117 firms across 17 industries/sectors that met the following criteria were interviewed:

- SMEs or businesses registered with the Investment Promotion Authority (IPA) and Internal Revenue Commission (IRC)

- SMEs that had loans with Bank South Pacific (BSP), which is the dominant commercial bank in PNG.

In addition to satisfying the above criteria, for businesses to qualify as SMEs they should have the following:

- Three to 150 paid employees,

- A maximum borrowing of PGK1.5 million and annual turnover of between PGK100,000 and PGK15 million qualified as SMEs.

However, in our study we used the alternative definition provided in the PNG Government’s SME policy (Department of Trade, Commerce and Industry 2016) to classify the firms as MSMEs.

3.2. Construction of the Main Variables

- 1.

- Classification of firms by size. We began by classifying the firms into MSMEs based on number of employees. In order to be to be consistent with our measure of firm growth, we used the employment-based definition provided by the Department of Trade, Commerce and Industry (2016) to classify the firms as MSMEs. Sectors such as agriculture, tourism, forestry, fisheries, and services are considered to be more labor intensive. Thus, the number of employees required in these sectors differ from manufacturing, engineering and construction sectors. The MSMEs classification according to size of employees and sector is the following:

- Micro enterprises. Firms that have fewer than five employees.

- Small enterprises. For manufacturing, engineering and construction sectors, number of employees ranges from 5 to 19, whereas for agriculture, tourism, forestry, fisheries and services it is 5 to 39 employees.

- Medium-size enterprises. For the case of manufacturing, engineering and construction sector, the number of employees is 20 to 99, whereas it is 39 to 99 for agriculture, tourism, fisheries, and services.

- In order to identify the sector that the surveyed firms, owners/and or managers of the firms were the product or services their firms provide. If they provide more than one product or service they were asked about the primary product that generated the greatest share of annual revenue. They were also asked about the number of paid employees their PNG offices, including full-time, part-time and casual.

We used the respective employment thresholds provided by the Department of Trade, Commerce and Industry (2016) to construct a categorical variable:

Micro enterprise = 1; small enterprise = 2; medium enterprise = 3.

- 2.

- Measures of growth. The survey we used had only one cross-section. However, the respondents answered the following two questions about employment, which allowed us to estimate the expected growth in employment: (1) How many employees are there in all your organization’s PNG offices, including full-time, part-time and casual? (2) Approximately how many new jobs will you provide in the next 12 months?

It was possible to construct two basic indicators for measuring the expected employment growth from the answers to these questions. The first one examines the simple difference between employment between two points in time while the second presents this difference relative to the initial (employment) size of the firm. Daunfeldt et al. (2014) have shown that these two measures can lead to different results: measures of absolute growth are biased towards larger firms, while measures of relative growth favor larger firms. To reduce these biases, we followed Reyes (2018) and calculated the midpoint growth rate, which uses the absolute changes relative to the average size of the firm across the two periods (2012 and 2013). We calculated employment growth as follows:

where employmenti,t refers to the number of employees that firm i has in PNG offices in year t. We also retained the log of employment in 2012 as an indicator of firm size, as described above.

- 3.

- Corruption obstacle. The survey question asked respondents to judge to what extent government corruption is an obstacle to business expansion or performance. We first coded the possible responses to this question on a 4-point scale as: 0 = Not an obstacle, 1 = Minor (small) obstacle, 2 = Moderate (middle) obstacle, and 3 = Major (big) obstacle. These scores indicate the respondents’ perception of both absolute and relative magnitudes of the severity of government corruption to business performance and expansion. As Levy (1993) has argued, a ranking in the 0–1 range signifies judgement that the absolute severity of government corruption is somewhat negligible; yet, an identical perception of relative severity of the same obstacle may have been ranked by another respondent in the 2–3 range. In such circumstances, nothing useful for policy can be gleaned from differences among entrepreneurs in their perceptions of the absolute magnitude of government corruption as an obstacle (Levy 1993). We therefore constructed the measure of government corruption obstacle, designated Corruption, by collapsing the four responses (“Not an obstacle”, “Minor (small) obstacle”, “Moderate (middle) obstacle”, and “Major (big) obstacle”) into a bivariate variable set equal to 1 if a respondent answered that government corruption was a moderate or major obstacle, and zero otherwise. So, the normalized scores along the scale of 0–1 measures the average difference between respondents who judged the effect of government corruption as least severe and those that judged the effect of government corruption as most severe.

- 4.

- Infrastructure obstacles. The survey contained several other different perceived obstacles to SME performance and expansion, four of which are related to infrastructure variables, namely electricity, water/sewerage, telecommunications and transport. The possible responses to the question of how big each obstacle was on a 4-point scale were: 0 = Not an obstacle, 1 = Minor (small) obstacle, 2 = Moderate (middle) obstacle, and 3 = Major (big) obstacle. The correlation between the electricity obstacle and two of the obstacles was quite high, ρ = 0.68 for water/sewerage and ρ = 0.55 for telecommunications. The correlation between water/sewerage and telecommunication services was also quite high (ρ = 0.53), but the correlation between the transportation obstacle and the other three infrastructure obstacles were somewhat low (ρ = 0.18 for electricity, ρ = 0.22 for water/sewerage, and ρ = 0.13 for telecommunications). Thus, these infrastructure obstacle variables represent distinct but connected measures of the perception about infrastructure as an obstacle to SME operation and expansion. The first principal component (with weights of 0.501, 0.513, 0.483, and 0.191) constructed for the set of 4-point scale responses for each of the four variables explained 56.41 percent of their overall variation. Therefore, we summarized the four sets of responses by averaging the degree of severity of each infrastructure obstacle. The resulting infrastructure obstacle measure for a given firm, designated Infrastructure, is an ordinal estimate of the severity of the infrastructure obstacle and has a maximum value of three and a minimum value of zero. As Table A1 in the Appendix A shows, the dispersion of Infrastructure is nearly similar for all firm sizes in the sample, suggesting homogeneity in firms’ perceptions about infrastructure as an obstacle to MSMEs.

- 5.

- Regulatory policy obstacles. Like infrastructure-related obstacles, this variable was first constructed as the average degree of the severity of regulatory policy obstacles related to government regulations, tax rates and crime/security for the firm. The severity of each of these obstacles was judged on a 4-point scale: 0 = Not an obstacle, 1 = Minor (small) obstacle, 2 = Moderate (middle) obstacle, and 3 = Major (big) obstacle. The correlation between government regulation and tax rates was high (ρ = 0.40), but the correlation between crime/security and the other two variables was low (ρ = 0.22 for government regulation and ρ = 0.16 for tax rates). However, the first principal component (with weights of 0.564, 0.526, and 0.379) constructed for the set of 4-point scale responses for each of the three variables explains 50.9 percent of their overall variation. We therefore summarized the four sets of responses by averaging the degree of severity of each regulatory policy obstacle, with the resulting measure, designated Regulation, being an ordinal estimate of the severity of the regulatory policy obstacle with a maximum value of three and a minimum value of zero. Table A1 in the Appendix A shows a relatively lower dispersion in the perception about regulatory policies as an obstacle to doing business among the medium-size firms, compared to their micro- and small-size counterparts.

3.3. The Empirical Model

The ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model assumes that errors in the dependent variable are uncorrelated with the independent variables (Greene 2003). In our study corruption variable has the potential to generate endogeneity problem in the model. This is because corruption variable would allow errors to be correlated across firms in a given region-province-location-industry (Wang and You 2012). Endogeneity problem often results in a biased coefficient in the OLS. In order to minimize the tendency of the problem, the Instrument Variable Two Stage Least Squares (IV-2SLS) regression model was used to explore the impact of corruption on employment growth in MSMEs while some independent variables were used as controls.

The survey questions used in this study also provided information about a firm’s principal place of business: region, province, and location (urban, rural, or remote) and industry/sector. For instrument variable, the average bivariate scores of normalized perceptions about government corruption across firms in a given sector/industry-location was taken and used as an instrument for the perception of corruption at the firm level. We also constructed instruments for infrastructure and regulatory policy obstacles in the same manner. In the first stage, the instrument variable was used to regress against independent variables using STATA statistical software as follows:

INSTRUMENT = β0 + β1·Corruption + β2·Regulation + β3·Infrastructure + β4·Controls + ε

The F-test value for the estimated first stage instrument variable (IV) regression range from 11 to 14, thus we proceeded to the second stage IV.

For the second stage, the employment growth responses were regressed on predicted values of corruption and other independent variables using STATA statistical software as follows:

where growth is expressed as the mid-point growth rate of the number of employees between 2012 and 2013. The Regulation and Infrastructure variables were included in order to incorporate interaction of firms with government institutions (Sharma and Mitra 2015). We also included the set of Controls, composed of firm and owner characteristics, described in Appendix A (Table A1).

growth = β0 + β1·Corruptionp + β2·Regulationp + β3·Infrastructurep + β4·Controlsp + ε

4. Results

4.1. Data Used for Analysis and Managers/Owners Perception of Corruption

Of the 1117 MSMEs surveyed, approximately four percent (42) of managers/owners of the firms answered: “Don’t know” to the question associated with the new jobs that the firm will provide in the next 12 months. Thus, the responses of the 42 managers/owners was excluded from this study because the employment growth of their firms cannot be calculated. Of the remaining 1075 observations, we excluded nine managers/owners who answered: “did not know” or did not answer the question associated with the extent to which government corruption is an obstacle to the expansion or performance of their business. Thus, 1066 observations were used in the continued analysis. However, it was found that two percent (21) of the 1066 observations belonged to large enterprises. As the focus of this study is MSMEs, large enterprises were excluded, which makes the number of observations used for analysis in this study to be 1045 observations. Of the 1045 observations, 20% were micro enterprises, 71% small enterprises, and 8% medium.

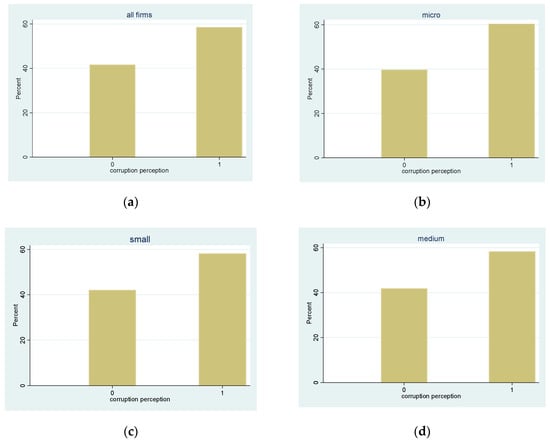

Regarding the perception of government corruption in relation firm size, the results show that managers/owners of MSMEs generally perceive corruption as bad for business (Figure 1). Almost 60% of all managers/owners of MSMEs perceive that government corruption is a big obstacle to their businesses whereas more than 40% perceived it as a minor obstacle.

Figure 1.

Distribution of normalized corruption perception by firm size. (Notes: 0 = Not an obstacle or minor (small) obstacle; 1 = moderate (middle) obstacle or major (big) obstacle). (a) All firms; (b) Micro; (c) Small; (d) Medium.

4.2. Econometric Estimates

In this section, we first report the results from estimating Equation (5) for all MSMEs using ordinary least squares (OLS) and IV-2SLS methods. We then classify the sample of firms into three different sizes—micro, small, and medium. Eight OLS and eight IV-2SLS regression models were estimated to examine the impacts of corruption and control variables on employment growth for all firms, micro enterprises, small-size enterprises and medium-size enterprises (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). The F value for the OLS models ranged from 1.78 to 9.81 and was statistically significant at the 5 percent level. This indicates that the results from our models had overall statistical significance. The coefficient of determination (R2) range from 11 percent to 34 percent. This indicates that the variability predicted by our OLS did not exceed 34 percent. In order to correct for endogeneity problems, the IV-2SLS model was applied. The Wald test statistical significant levels range from 1% to 5%. This indicates that the models had overall significance. Thus, the IV-2SLS was used in the analysis.

Table 1.

Regression estimates of employment growth for all firms.

Table 2.

Regression estimates of employment growth for microenterprises.

Table 3.

Regression estimates of employment growth for small-size enterprises.

Table 4.

Regression estimates of employment growth for medium-size enterprises.

The results revealed that the coefficients associated with corruption for all firms and the medium-size enterprises models were positive and statistically significant (Table 1 and Table 4). This indicates that the presence of the most severe corruption obstacle increases employment growth in all firms and especially in firms that were medium-size enterprises. In terms of elasticity, the presence of the most severe corruption obstacle in all firms was associated with an increase in employment growth by 0.1 percent. For the case of corruption in medium-size enterprises, it increased employment growth by 0.4 percent.

The results of the control variables (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4) showed that the coefficient associated with regulatory policy obstacle for all firms, micro enterprises, and small-size enterprises was negative and statistically significant. This implies that an increase in regulatory policy obstacle in all firms and micro enterprises is associated with a decrease in employment growth. On the other hand, the coefficient associated with firm size for all firms and small-size enterprises was negative and statistically significant. This indicates that an increase in firm size for all firms and small-size enterprises is associated with a decrease in employment growth. An increase in firm age is associated with an increase in employment growth for all firms. An increase in fixed asset per employee ratio is associated with an increase in employment growth for all the models. The presence of the coefficient associated with sole trader is associated with a decrease in employment growth in the microenterprises model, whereas it increases growth in the small-size enterprises. Furthermore, the presence of males in the top management, retail-dominated sector and Indigenous-owned firms is associated with an increase in employment growth.

In terms of elasticity, the most important control variables were firm size for all firms and small-size enterprises, whereas fixed asset per employee is the most important variable for microenterprises and medium-size enterprises models.

5. Discussion

The findings from this study revealed that MSME managers/owners who perceive corruption in government institutions as a major obstacle to businesses are likely to achieve employment growth in their firm. This suggests that if government institutions in a country are not working well, illegal payments to corrupt government officials might be required to make the institutions work. Our findings conform to the premise that, in countries where corruption associated with public institution is an obstacle to businesses, it is necessary to “grease the wheels” of these institutions for them to work. This is in line with the findings of Sharma and Mitra (2015), who found that bribing government officials is associated with an increase in firms’ export performance and product innovation. They concluded that bribery is required for government institutions to work. Corruption is widespread in PNG’s public sector, and people often find it difficult to resist corruption because of the presence of structural issues associated with the sector (Payani 2000; Walton 2009). Thus, some people are compelled to bribe corrupt government officials to access services provided by the public sector. Corruption in the country is often associated with favoritism and nepotism (Walton 2016). This contributes to the allocation of contracts in a disorderly manner, and firms that do not have the capacity often win the tenders to execute the contracts. In addition, misappropriation of public funds that has been earmarked for improving formal institutions has been a long-standing issue. This contributes to the decay of these institutions, which provides a further avenue for corrupt practices to prevail.

Efficiency and transparency in the tender process could be promoted by the use of open tenders, and conflict of interest declared by all government officials involved in the tender process. This has the potential of promoting fairness and transparency in the tender process, which allows all firms to be treated equally regardless of their social and political affiliations. Furthermore, in order to reduce bribery, strategies that promote better tax compliance by improving transparency in the taxation process and provision of quality government services are required.

Strategies that promote proper accountability of government agencies are necessary for tax compliance to work well.

Countries that have history of corruption in the public sector often perform poorly in the ease of doing business index. For example, PNG ranked 141 among 190 countries in 2014 and 108 in 2018 (Trading Economics 2018). This indicates that there are several impediments that restrict the proper functioning of the public sector in the country, such as the bureaucracy, inadequate capacity and poor government regulations.

For MSMEs to operate successfully in developing countries such as PNG, they must develop coping strategies that can enable them to mitigate the impediments to doing business. This could be a reason that MSMEs managers/owners that perceived public sector corruption as major obstacle to businesses had an increase in employment growth in their firms. Our findings are in line with authors such as Wang and You (2012), who found that corruption increases firm’s revenue from sales in China. Williams and Martinez-Perez (2016) found that corrupt practices increased firms’ sales and productivity in developing countries. In a Turkish study, Ayaydin and Hayaloglu (2014) found that manufacturing firms that are involved in making corrupt payments to public officials had increased growth. Blagojevic and Damijan (2012) concluded that private firms that offer bribes to public officials will have higher productivity than those that do not offer bribes. Our findings suggest that the need to mitigate the corruption obstacle in MSMEs appears to be a rational economic choice that often benefits MSMEs. This is because the formal institutions in countries that have corrupt practices in the public sector are often saddled with bureaucracy, inefficiency and capacity problems. Thus, bribing government officials by MSMEs managers might assist in compensating for the imperfections in formal institutions. This is because the bribe could be seen as “speed money”, which assists the MSMEs to circumvent the bureaucracy and inefficiencies in the public sector, as well as trigger employment growth.

Of all the categories of MSMEs that were explored in this study, our findings revealed that the medium-size enterprises had the greatest capacity to tackle severe corruption obstacle. A possible reason is that they often have greater economic power and skills than other categories of the MSMEs that can be used to cope with the corruption obstacle. In addition, medium-size enterprises are better equipped experience to influence the behavior of governmental officials, which provides them with the opportunities to benefit more from institutional failures and results in employment growth. This conforms to the findings of Tanzi and Davoodi (2000), who found that large firms are less vulnerable to the impacts of corruption than smaller firms because they have skills for bypassing government regulations and tax laws. Our findings suggest that micro enterprises and small-size enterprises might be hit harder by corruption because of the cost burden associated with it.

MSMEs have the potential to benefit from formal institutions that have been infested with corrupt practices. However, this might not be an optimal strategy at the aggregate country level, as reported by Williams and Martinez-Perez (2016). Several authors, such as Mendez and Sepulveda (2006) and Meon and Sekkat (2005), have shown that corruption impedes the economic growth and development of a country. Others (e.g., Donadelli and Persha 2014; Faruq et al. 2013) have shown that economies that are highly prone to corruption are strongly linked to poor firm performance. Although the engagement in corrupt practices with government officials can be seen as a rational economic behavior that benefits MSMEs, it is a cost to a country as a whole. However, in order to develop a strategy for combating corruption, it is important to note that accepting the payment of bribes to corrupt government officials by an individual is an economic rational decision which is as a result of the failures of formal institutions. Drawing lessons from the utilitarian theory of crime, the MSME managers can be seen as rational economic agents who assess the opportunities and risks they face. The managers will tend to engage in corrupt practices if the expected penalties and probability of being caught are less than the benefits they receive (Allingham and Sandmo 1972). In order to discourage MSME operators from providing bribes to corrupt government officials, a strategy that increases the risks of being caught and penalty associated with corruption could be introduced. However, this will tend to be more effective public institutions is working well.

According to grounded institutional theory, corruption emanates from the failures of formal institutions and the entrepreneurs’ norms, values and beliefs that are often not in line with the existing laws and regulations (De Castro et al. 2014; Williams and Shahid 2016). The government of developing countries such as PNG could tackle corruption by developing strategies to address the failures of public institutions. The information asymmetry between formal and informal institutions that generates corruption should also be addressed. This could be achieved by raising public awareness through advertising campaigns about the costs of corruption. It is essential to improve the quality of governance and increase the capacity of formal institutions by employing competent personnel and better training of current employees.

The utilitarian theory and institutional theory approach could be combined to tackle corruption in PNG. This could be based on the “slippery slope framework” (Kirchler et al. 2008). This entails the use of voluntary and enforced compliance, as well as increasing the capacity of government agencies to reduce institutional deficiencies. In addition, the costs (i.e., penalties) associated with corrupt practices could be increased so as to discourage people from engaging in such practices. Regulations that assist MSME managers to regulate themselves in a manner that is in line with the law by correcting failures in formal institutions could be introduced. Measures that increase the costs of corruption could be introduced to account for people who might refuse to comply to laws and regulations, as recommended by Braithwaite (2009). This should be followed by the promotion of zero tolerance for corruption. Furthermore, voluntary compliance and incentives could be introduced to enhance the benefits of not engaging in corrupt practices.

6. Conclusions

This study provides an insight into the impact of corruption in the public sector on employment growth in MSMEs as perceived by their managers/owners. The findings reveal that corruption is associated with an increase in employment growth. However, the growth is strongly linked to firm size. Of all the categories of MSMEs, the medium-size enterprise is the most favored by public sector corruption. The increase in employment growth in MSMEs as a result of corrupt practices is evidence of the failures of formal institutions in the public sector of a developing country such as PNG. This has the potential of restricting innovation, competitiveness and efficiencies in the MSMEs. In addition, the State loses revenue that should have accrued to it from tax. Considering that MSMEs have the potential to contribute significantly to a country’s economy, it is important to tackle corruption. The bribery of some corrupt government officials by private individuals is a rational economic decision, which is a product of the failures of government institutions. If the intention is to tackle corruption, strategies that promote a zero tolerance for corruption should be developed. This could be achieved by addressing the failures associated with government institutions. This include the improvement of quality of governance and increasing the capacity of the institutions through recruitment of more competent personnel and providing training opportunities for existing employees. The information asymmetry that exists between formal and informal institutions could be reduced by promoting public awareness on the costs associated with corruption. The risk associated with being caught and corresponding penalties could be increased. Furthermore, people who promote anti-corruption practices could be rewarded as a way of encouraging them to continue the practices. The findings from this study would assist policy makers and planners in the development and implementation of anti-corruption strategies by considering the impacts of corruption on the economy. It would also contribute to strategies that promote ease of doing business, which could be used to tackle the obstacles that MSMEs face in developing countries including PNG.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.O. and E.E.E.; methodology, F.O. and E.E.E.; software, F.O.; validation, E.E.E.; formal analysis, F.O.; writing—original draft, E.E.E., F.O. and P.K.; writing—review and editing, E.E.E., F.O. and P.K.

Funding

This paper was prepared as part of a research project supported by funds provided to the Papua National Research Institute, Papua New Guinea by the Australian Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ronald Sofe, Research Fellow, National Research Centre, Papua New Guinea. The author thanks Chris Hoy and Grant Walton for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Definition of variables.

Table A1.

Definition of variables.

| Name of Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |

| Growth | Growth in employment, calculated as the absolute change in the number of people employed between 2012 and 2013 relative to the average size of the firm across the two periods. Employment in 2012 is the number of a firm’s employees in PNG offices. Employment in 2013 is number of employees in 2012 plus estimated number of new jobs a firm will provide in the next 12 months. |

| Endogenous Variables | |

| corruption obstacle | Firm-level corruption obstacle. Binary variable taking the value of 1 if corruption obstacle is moderate or major, 0 otherwise. |

| infrastructure obstacle | Firm-level infrastructure obstacle. Average score of degree of infrastructure obstacle (related to electricity, water and sewerage, telecommunications and transport) for the firm. Severity of each obstacle is judged on a four-point scale: 0 = Not an obstacle, 1 = Minor (small) obstacle, 2 = Moderate (middle) obstacle, 3 = Major (big) obstacle |

| regulatory obstacle | Firm-level regulatory policy obstacles. Average score of degree of regulatory policy obstacle (related to government regulation, tax rates and crime/security) for the firm. Severity of each obstacle is judged on a four-point scale: 0 = Not an obstacle, 1 = Minor (small) obstacle, 2 = Moderate (middle) obstacle, 3 = Major (big) obstacle |

| Instrumental Variables | |

| industry/sector corruption obstacle | Average location-industry/sector corruption obstacle |

| industry/sector infrastructure obstacle | Average location-industry/sector infrastructure obstacle |

| industry/sector regulatory obstacle | Average location-industry/sector regulatory policy obstacle |

| Control Variables/Additional Instruments | |

| Firm size (log employment) | Total employment in 2012, in logarithm |

| Firm age (log age of firm in years) | Number of years the business has been going for, in logarithm. Age of firm is the number of years the business has been going for since the year it was established. |

| Export-import trade | Trivalent variable taking the value of 2 if a firm spent a percentage of annual sales/turnover to both import purchases from overseas and generated a fraction annual sales/turnover from export sales, 1 if a percentage of sales/turnover was spent on either import purchases or generated from export sales, and 0 otherwise |

| % of firm shares owned by foreigners | % of firm owned by private foreign individuals or organizations |

| K/L ratio (log fixed assets per employee) | Total value of fixed assets divided by number of employees, both in 2012, in logarithm. Fixed assets consist of land, buildings and machinery. |

| Dominant business type (Sole trader) | Binary variable taking the value of 1 if firm is sole proprietorship, 0 otherwise |

| Gender of top management | Binary variable taking the value of 1 if the composition a firm’s top managers are men or more than 50% men or all men (i.e., no women), 0 otherwise |

| Dominant sector (Retail) | Binary variable taking the value of 1 if the firm belongs to the dominant sector, which is retail trade with more than 50% of all firms, 0 otherwise |

| Indigenous | Nationality of largest owner. Binary variable taking the value of 1 if indigenous Papua New Guineans are the current largest owners of the firm, 0 otherwise |

| Region dummy | Region dummy variable, taking the value of one (1) if region is Southern, zero (0) otherwise |

| Location dummy | Location dummy variable, taking the value of one (1) if location is Urban, zero (0) otherwise |

| Region fixed effects | Categorical variable: Southern = 1, Momase = 2, Highlands = 3, Islands = 4 |

| Location fixed effects | Categorical variable: Urban = 1, Rural = 2, Remote = 3 |

| Sector fixed effects | Two-digit International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) level, Categorical: A = 1, B = 2, …, Q = 17 |

| Size of firm in 2012 | Categorical variable taking the values of 1, 2, 3 and 4 if a firm is, respectively, micro, small, medium and large enterprise based on employment threshold set by the government of PNG. |

| Firm life cycle | Firm growth life cycle fixed effects—partitions the sample of firms into three different age categories from young to old: 0–4 (young), 5–9 (middle-age), 10+ (mature age) years |

References

- Abed, George T., and Sanjeev Gupta. 2002. Governance, Corruption and Economic Performance. Washington: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James Robinson. 2012. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power. New York: Crown Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Allingham, Michael G., and Agnar Sandmo. 1972. Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics 1: 323–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, Elizabeth, and James Freeman. 2009. The Effect of Corruption on Investment Growth: Evidence from Firms in Latin America, Transition Countries. Lawrence: Department of Economics, University of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasouli, Daphne, Antoine Goujard, and Pantelis Sklia. 2012. Corruption and firm performance: Evidence from Greek firms. International Journal of Economic Sciences and Applied Research 5: 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaydin, Hasan, and Pınar Hayaloglu. 2014. The effect of corruption on firm growth: Evidence from firms in Turkey. Asian Economic and Financial Review 4: 607–24. [Google Scholar]

- Begovic, Boris. 2005. Corruption: Concepts, Types, Causes and Consequences. Buenos Aires: Center for the Opening and Development of Latin America (CADAL). [Google Scholar]

- Blagojevic, Sandra, and Jože P. Damijan. 2012. Impact of Private Incidence of Corruption and Firm Ownership on Performance of Firms in Central and Eastern Europe (LICOS Discussion Paper 310/2012). Leuven: Centre for Institutions and Economic Performance. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, Valerie. 2009. Defiance in Taxation and Governance: Resisting and Dismissing Authority in a Demoncracy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Daunfeldt, Sven-Olov, Niklas Elert, and Dan Johansson. 2014. The economic contribution of high-growth firms: Do policy implications depend on the choice of growth indicator? Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 14: 337–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Jin-Wook. 2009. Institutional structures and effectiveness of anti corruption agencies: A comparative analysis of South Korea and Hong Kong. Asian Journal of Political Science 17: 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, Julio O., Susanna Khavul, and Garry D. Bruton. 2014. Shades of grey: How do informal firms navigate between macro and meso institutional environments? Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 8: 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waldemar, Felipe Starosta. 2012. New products and corruption: Evidence from Indian firms. The Developing Economies 50: 268–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadelli, Michael, and Lauren Persha. 2014. Understanding emerging market equity risk premia: Industries, governance and microeconomic policy uncertainty. Research in International Business and Finance 30: 284–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Trade, Commerce and Industry. 2016. Papua New Guinea Small and Medium Enterprises Policy 2016. Port Moresby: Government of Papua New Guinea. [Google Scholar]

- Ezebilo, Eugene E. 2011. Local participation in forest and biodiversity conservation in Nigerian rainforest. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 18: 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruq, Hasan, Michael Webb, and David Yi. 2013. Corruption, bureaucracy and firm productivity in Africa. Review of Development Economics 17: 117–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, Martin, and Icek Ajzen. 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Fisman, Raymond, and Jakob Svensson. 2007. Are corruption and taxation really harmful to growth? Firm level evidence. Journal of Development Economics 83: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, Manuela, and Nicola Pontara. 2007. Does Corruption Impact on Firms’ Ability to Conduct Business in Mauritania? Evidence from Investment Climate Survey Data. Policy Research Working paper. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Gaviria, Alejandro. 2002. Assessing the effects of corruption and crime on firm performance: evidence from Latin America. Emerging Markets Review 3: 245–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbetnkom, Daniel. 2017. Corruption and small and medium sized enterprise growth in Cameroon. In Inclusive Growth in Africa: Polices, Practice and Lessons Learnt. Edited by Steve Kayizzi-Mugerwa, Abebe Shimeles, Angela Lusigi and Ahmed Moummi. New York: Routledge, pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, William H. 2003. Econometric Analysis, 5th ed. Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River. [Google Scholar]

- Hanousek, Jan, Anastasiya Shamshur, and Jiri Tresl. 2017. Firm efficiency, foreign ownership and CEO gender in corrupt environments. Journal of Corporate Finance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoon, Deborah, and Finn Heinrich. 2013. Global Corruption Barometer. Berlin: Transparency International. [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, Gretchen, and Steven Levitsky. 2004. Informal institutions and comparative politics: A research agenda. Perspectives on Politics 2: 725–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47: 263–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, Charles. 2007. Corruption, Construction and Developing Countries. World Bank Policy Research Working paper 4271. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler, Erich, Erik Hoelzl, and Ingrid Wahl. 2008. Enforced versus voluntary tax compliance: The slippery slope framework. Journal of Economic Psychology 29: 210–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, Nathaniel H. 1964. Economic development through bureaucratic corruption. American Behavioural Scientist 8: 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Brian. 1993. Obstacles to developing indigenous small and medium enterprises: An empirical assessment. The World Bank Economic Review 7: 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, Fabio, and Facundo Sepulveda. 2006. Corruption, growth and political regimes: Cross country evidence. European Journal of Political Economy 22: 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meon, Pierre-Guillaume, and Khalid Sekkat. 2005. Does corruption grease or sand the wheels of growth? Public Choice 122: 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payani, Hela Hengene. 2000. Selected problems in the Papua New Guinean Public Service. Asian Journal of Public Administration 22: 135–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Jun, and Philip E. Strahan. 2007. How laws and institutions shape financial contracts: The case of bank loans. Journal of Finance 62: 2803–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, José-Daniel. 2018. Effects of FDI on High Growth Firms in Developing Countries. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Chandan, and Arup Mitra. 2015. Corruption, governance and firm performance: Evidence from Indian enterprises. Journal of Policy Modeling 37: 835–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. 1993. Corruption. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 108: 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, Vito, and Hamid R. Davoodi. 2000. Corruption, Growth, and Public Finances. IMF Working paper 182. Washington: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Trading Economics. 2018. Ease of Doing Business in Papua New Guinea. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/papua-new-guinea/ease-of-doing-business (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- Tebbutt Research. 2014. Report for SME Baseline Survey for the Small Medium Enterprise Access to Finance Project. Port Moresby: Department of Trade, Commerce and Industry. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, Paul, and Niels Noorderhaven. 2016. A users’ perspective on corruption: SMEs in the hospitality sector in Kenya. African Studies 75: 114–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, Virginie, and Julien Hanoteau. 2010. Corruption, manufacturing plant growth and the Asian paradox: Indonesian evidence. World Development 38: 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, Grant W. 2009. Rural People’s Perceptions of Corruption in Papua New Guinea. Port Moresby: Transparency International Papua New Guinea. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, Grant W. 2015. Defining corruption where the state is weak: The case of Papua New Guinea. The Journal of Development Studies 51: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, Grant W. 2016. Silent screams and muffled cries: The ineffectiveness of anti-corruption measures in Papua New Guinea. Asian Education and Development Studies 5: 211–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yuanyuan, and Jing You. 2012. Corruption and firm growth: Evidence from China. China Economic Review 23: 415–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. 2018. Global Investment Competitiveness Report 2017/2018: Foreign Investor Perspectives and Policy Implications. Washington: IBRD/The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Colin C., and Ioana Horodnic. 2015. Explaining the prevalence of the informal economy in the Baltics: An institutional asymmetry perspective. European Spatial Research and Policy 22: 127–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Colin C., and Alvaro Martinez-Perez. 2016. Evaluating the impacts of corruption on firm performance in developing economies: An institutional perspective. International Journal of Business and Globalisation 16: 401–22. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Colin C., and Muhammad Shahid. 2016. Informal entrepreneurship and institutional theory: Explaining the varying degrees of (in) formalisation of entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 28: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolford, Don. 1976. Papua New Guinea: Initiation and Independence. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).