Effects of Diverse Property Rights on Rural Neighbourhood Public Open Space (POS) Governance: Evidence from Sabah, Malaysia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rural Neighbourhood Residential Commons: POS Quality as a CPR

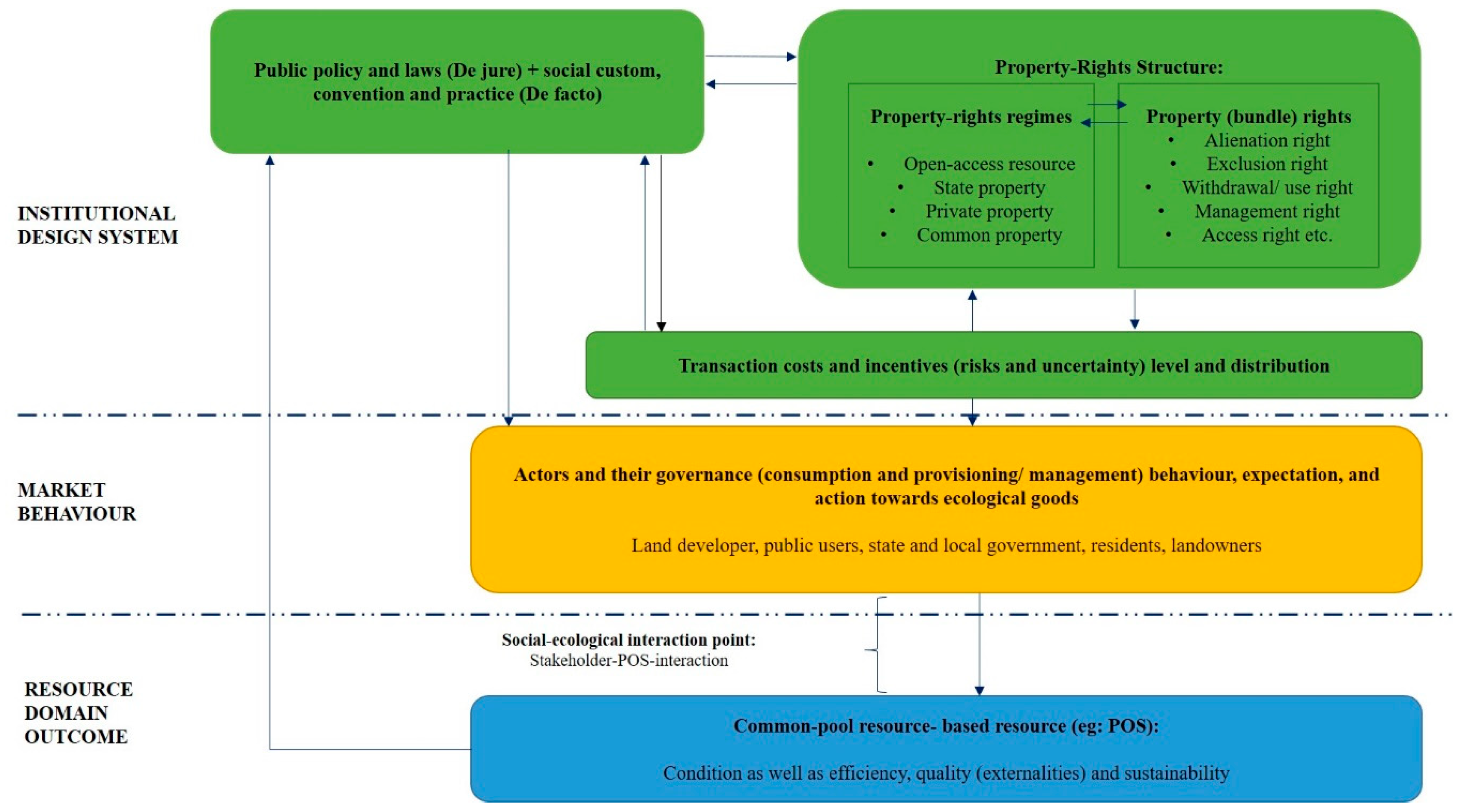

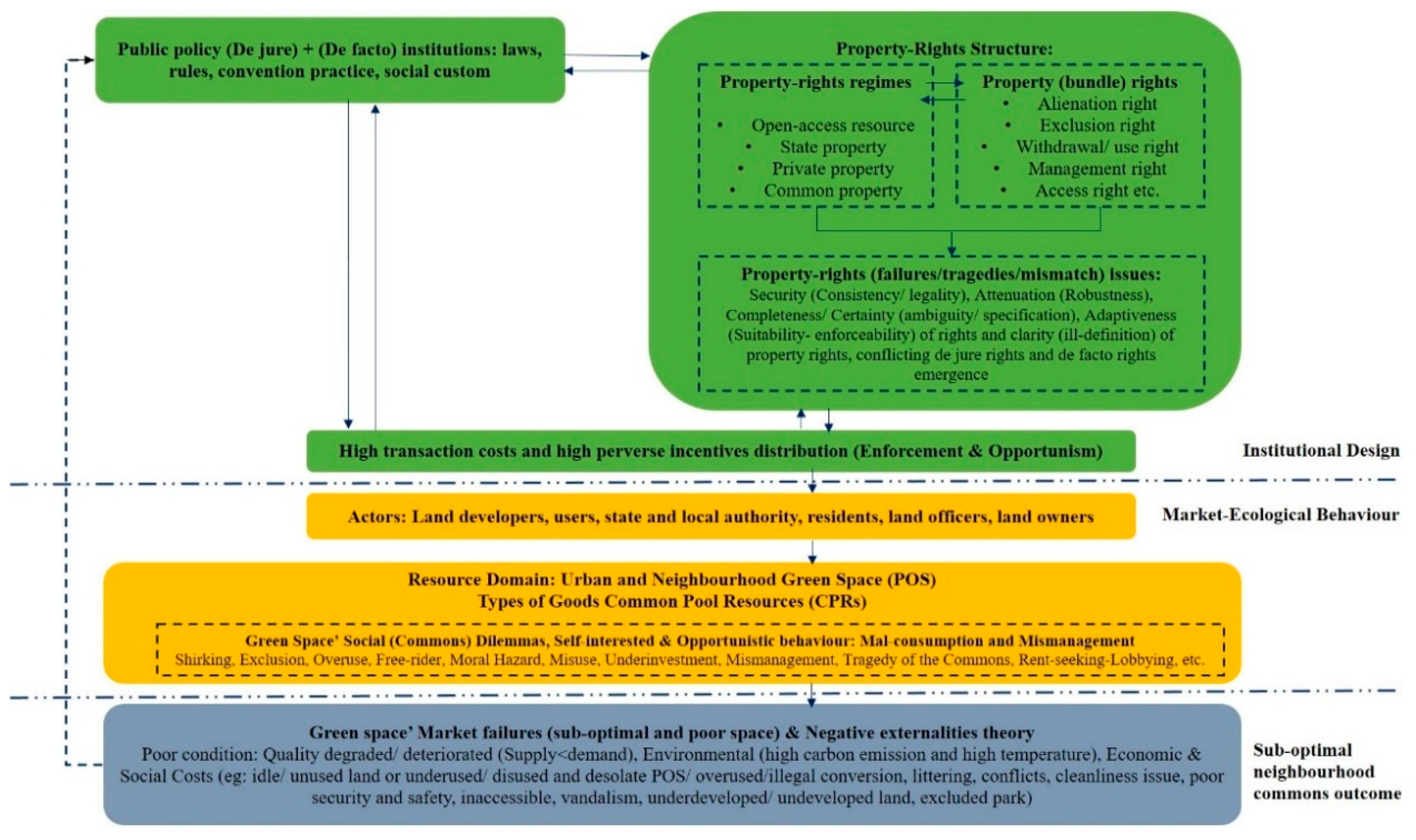

3. SES Framework and NIE Theories: Interplay between Institutions, POS Governance and Social Dilemmas

3.1. Institutions

3.2. Transaction Costs

3.3. Property Rights System

4. A Social-Ecological System-Based New Institutional Economics Conceptual Framework

4.1. Concepts of Opportunistic Behaviour (Opportunism)

4.2. Commons Dilemmas and Negative Externalities in Rural Neighbourhood POS

4.3. Implication of Property Rights Failures on POS Governance and Quality

4.3.1. Attention (Robustness and Strength) of Property Rights

4.3.2. Incompleteness (Uncertainty) of Property Rights

4.3.3. Mal-Assignment of Property Rights

4.3.4. Insecurity of Property Rights

4.3.5. Conflict between de Facto Property Rights with the de Jure Rights System

5. Methodology

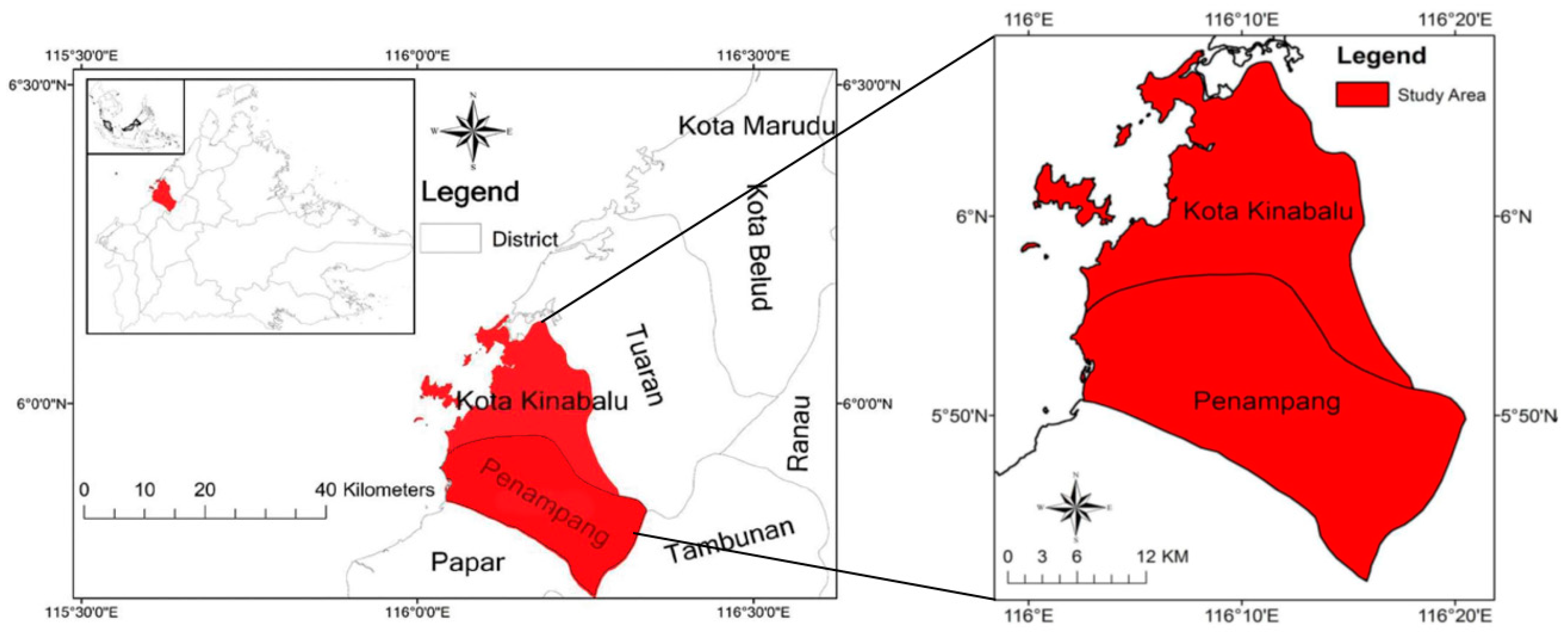

5.1. Study Area

5.2. Sabah’s Land and Planning Systems on Residential POS Property Rights Distributions

5.3. Respondents Sampling

5.4. Methods and Procedures

5.5. Qualitative and Statistical Analyses

6. Results and Findings

6.1. Residents’ Perception of the Current System of POS Management and Consumption

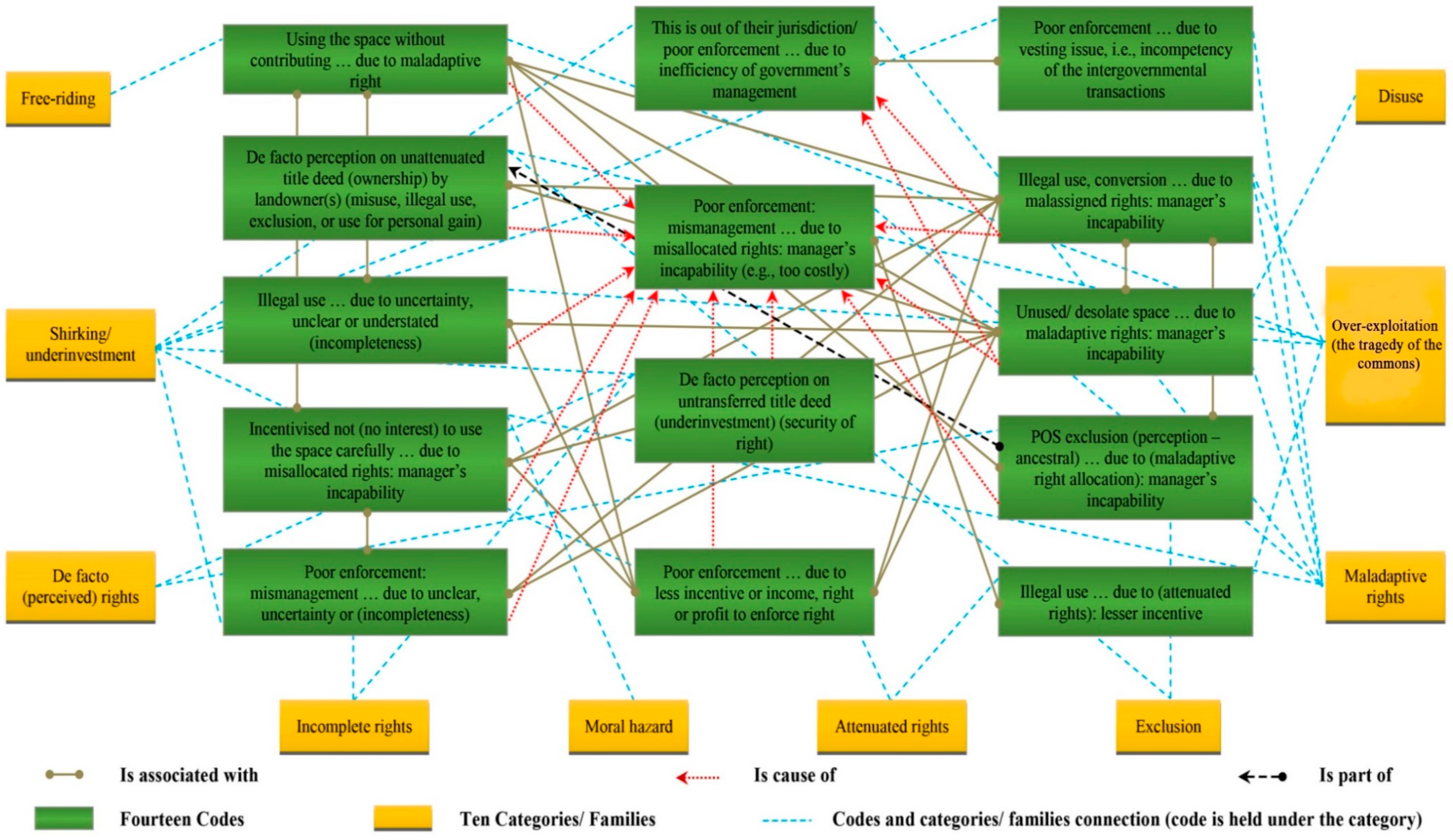

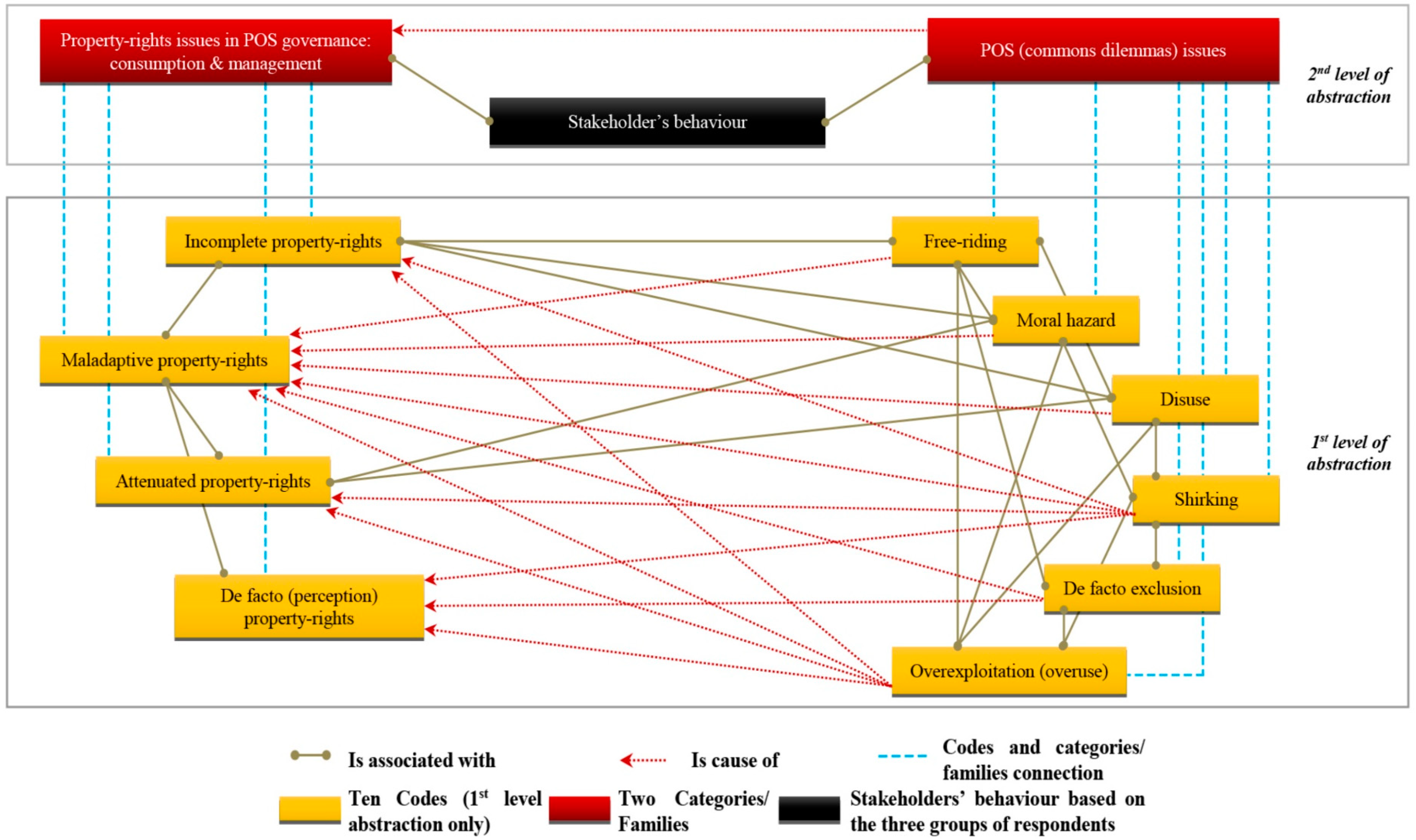

6.2. Synthesis of All Stakeholders’ Findings on Local Property Rights Issues and POS Dilemmas

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboriginal Peoples Act. 1954. Malaysia. Aboriginal Peoples Act 1954. In Act 134. Edited by Department of Director General of Lands and Minerals Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Bhd. [Google Scholar]

- Agboola, Oluwagbemiga Paul, Muhammad Farid Azizul, Mohd Hisyam Rasidi, and Ismail Said. 2018. The cultural sustainability of traditional market place in Africa: A new research agenda. Journal of Rural Studies 62: 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchian, Armen A., and Harold Demsetz. 1973. The property right paradigm. The Journal of Economic History 33: 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, Lee J., Edwyna Harris, and Bernardo Mueller. 2009. De facto and de Jure Property Rights: Land Settlement and Land Conflict on the Australian, Brazilian and US Frontiers. No. w15264. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Scott, and Kimberly D. Krawiec. 2005. Incomplete contracts in a complete contract world. Florida State University Law Review 33: 725–55. [Google Scholar]

- Baur, Ivo, and Heinrich Nax. 2018. Adapting Governance Incentives to Avoid Common Pool Resource Underuse: The Case of Swiss Summer Pastures. Sustainability 10: 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boydell, Spike, and Glen Searle. 2014. Understanding property rights in the contemporary urban commons. Urban Policy and Research 32: 323–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Alison. 2015. Claiming the streets: Property rights and legal empowerment in the urban informal economy. World Development 76: 238–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, Susan J. 1998. The Global Commons: An Introduction. Washington: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, John L., Charles Quincy, Jordan Osserman, and Ove K. Pedersen. 2013. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociological Methods & Research 42: 294–320. [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Arce, Pablo, and Thomas Kittsteiner. 2011. Opportunism and Incomplete Contracts. RWTH Aachen University. Mode of Access. Available online: http://www.mikrooekonomie.rwth-aachen.de/workingpaper/Opportunism_and_Incomplete_Contracts.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2015).

- Chirwa, Ephraim. 2008. Land Tenure, Farm Investments and Food Production in Malawi. Discussion Paper 18. Institutions and Pro-Poor Growth (IPPG) Research Programme. Manchester: University of Manchester. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, Ronald H. 1960. The problem of social cost. In Classic Papers in Natural Resource Economics. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 87–137. [Google Scholar]

- Colding, Johan, Stephan Barthel, Pim Bendt, Robbert Snep, Wim van der Knaap, and Henrik Ernstson. 2013. Urban green commons: Insights on urban common property systems. Global Environmental Change 23: 1039–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coloma, Germán. 2001. An economic analysis of horizontal property. International Review of Law and Economics 21: 343–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2007. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Demsetz, Harold. 1967. Towards a theory of property rights. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 57: 347–59. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. 2017. Census and Local Authorities in Malaysia; Putrajaya: Department of Statistics Malaysia.

- Feder, Gershon. 1988. Land Policies and Farm Productivity in Thailand. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (FOA). 2002. Land Tenure and Rural Development. Rome: FAO Land Tenure Studies, No. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Sheila R., and Christian Iaione. 2016. The city as a commons. Yale Law & Policy Review 34: 281. [Google Scholar]

- Frech, Harry E., III. 1976. The property rights theory of the firm: Empirical results from a natural experiment. Journal of Political Economy 84: 143–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furubotn, Eirik G., and Svetozar Pejovich. 1972. Property rights and economic theory: A survey of recent literature. Journal of Economic Literature 10: 1137–62. [Google Scholar]

- Galiani, Sebastian, and Ernesto Schargrodsky. 2010. Property rights for the poor: Effects of land titling. Journal of Public Economics 94: 700–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafton, R. Quentin. 2000. Governance of the Commons: A Role for the State? Land Economics 76: 504–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, Garrett. 1968. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162: 1243–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hart, Oliver. 1995. Firms, Contracts, and Financial Structure. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heltberg, Rasmus. 2002. Property rights and natural resource management in developing countries. Journal of Economic Surveys 16: 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Brooks A., Melina Kourantidou, and Linda Fernandez. 2018. A case for the commons: The Snow Crab in the Barents. Journal of Environmental Management 210: 338–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Annette M. 2004. A market without the ‘right’ property rights. Economics of Transition 12: 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jongwook, and Joseph T. Mahoney. 2005. Property rights theory, transaction costs theory, and agency theory: An organizational economics approach to strategic management. Managerial and Decision Economics 26: 223–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Lawrence W. C., Stephen N. G. Davies, and F. T. Lorne. 2015. Creation of property rights in planning by contract and edict: Beyond “Coasian bargaining” in private planning. Planning Theory 15: 418–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Gabriel Hoh Teck. 2017. Institutional Property Rights of Residential Public Open Space in Sabah, Malaysia. Ph.D. thesis, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bahru, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Gabriel Hoh Teck. 2019a. A Perspective on Social-Ecological System Framework and New Institutional Economics Theories in Explaining Public Open Space (POS) Governance and Quality Issues. Journal of Design and Built Environment. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Gabriel Hoh Teck. 2019b. Ostrom’s Collective-Action in Neighbourhood Public Open Space (NPOS): Evidence from Sabah, Malaysia. Institutions and Economies. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Gabriel Hoh Teck, and Pau Chung Leng. 2018. Ten Steps Qualitative Modelling: Development and Validation of Conceptual Institutional-Social-Ecological Model of Public Open Space (POS) Governance and Quality. Resources 7: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Gabriel Ling Hoh Teck, Chin Siong Ho, Hishamuddin Mohd Ali, and Tu Fan. 2016. Do institutions matter in neighbourhood commons governance? A two-stage relationship between diverse property-rights structure and residential public open space (POS) quality: Kota Kinabalu and Penampang, Sabah, Malaysia. International Journal of the Commons 10: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Gabriel Hoh Teck, Chin Siong Ho, Kar Yen Tsau, and Chin Tiong Cheng. 2019. Interrelationships between Public Open Space, Common Pool Resources, Publicness Levels and Commons Dilemmas: A Different Perspective in Urban Planning. International Journal of Built Environment and Sustainability 6: 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Hua, and Hualin Xie. 2018. Impact of changes in labor resources and transfers of land use rights on agricultural non-point source pollution in Jiangsu Province, China. Journal of Environmental Management 207: 134–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, Joseph T. 2005. Economic Foundations of Strategy. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Markussen, Thomas. 2008. Property Rights, Productivity, and Common Property Resources: Insights from Rural Cambodia1. World Development 36: 2277–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarter, Matthew W., Anya Samek, and Roman M. Sheremeta. 2014. Divided loyalists or conditional cooperators? Creating consensus about cooperation in multiple simultaneous social dilemmas. Group & Organization Management 39: 744–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, Cyrus R., and Nitin R. Patel. 2011. IBM SPSS Exact Tests. Armonk: IBM Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Miyanaga, Kentaro, and Daisaku Shimada. 2018. The tragedy of the commons’ by underuse: Toward a conceptual framework based on ecosystem services and satoyama perspective. International Journal of the Commons 12: 332–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musole, Maliti. 2009. Property rights, transaction costs and institutional change: Conceptual framework and literature review. Progress in Planning 71: 43–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicita, Antonio, Matteo Rizzolli, and Maria Alessandra Rossi. 2007. Towards a theory of incomplete property rights. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- North, Douglass C. 1991. Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives 5: 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, Elinor. 2009. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Geoffrey, Alain Durand-Lasserve, and Carole Rakodi. 2009. The limits of land titling and home ownership. Environment and Urbanization 21: 443–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinckney, Thomas C., and Peter K. Kimuyu. 1994. Land tenure reform in East Africa: Good, bad or unimportant? Journal of African Economies 3: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, Anatol. 1998. Decision Theory and Decision Behaviour. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sabah Housing and Real Estate Developers Association (SHAREDA). 2014. Members in Kota Kinabalu. Sabah: SHAREDA. [Google Scholar]

- Sabah Land Ordinance. 1930. State of Sabah Land Ordinance (Sabah Cap. 68). Land Ordinance. Available online: http://www.lawnet.sabah.gov.my/Lawnet/SabahLaws/StateLaws/LandOrdinance.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2013).

- Sangmoo, K. 2015. Public spaces–not a ‘nice to have’ but a basic need for cities’. End Poverty in South Asia. [Google Scholar]

- Schlager, Edella, and Elinor Ostrom. 1992. Property-rights regimes and natural resources: A conceptual analysis. Land Economics 68: 249–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiebout, Charles M. 1956. A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy 64: 416–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, Christopher J. 2007. Property rights, public space and urban design. Town Planning Review 78: 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, Christopher J., and Lawrence Wai-Chung Lai. 2003. Property Rights, Planning and Markets: Managing Spontaneous Cities. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, Chris, Fulong Wu, Fangzhu Zhang, and Chinmoy Sarkar. 2016. Informality, property rights, and poverty in China’s “favelas”. World Development 78: 461–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Oliver E. 1975. Markets and Hierarchies. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Oliver E. 2000. The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature 38: 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, James Q., and George L. Kelling. 1982. Broken windows. Atlantic Monthly 249: 29–38. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Urban and rural public open spaces concerning spatiality (e.g., location, shape, and size) and architecture have been strategically planned in the design stage, and the provision of facilities is sufficient, which overall give quality spaces. However, such good condition and quality of POS may not be sustained due to defective consumption and management behaviour issues of individuals. |

| 2 | The terms including rural POS, POS, rural commons, rural neighbourhood commons, local POS, and neighbourhood residential commons are used interchangeably in this paper because they signify the same resources within the rural setting. |

| 3 | “As a result of ambiguous and ill-defined property rights, it is a phenomenon where different self-interested individuals are granted with unrestricted consumption and access rights (freedom) to the given open-access resource (pasture) without any cost-effective mechanism to monitor, manage and regulate others’ uses; therefore, the rivalrous CPR resource is vulnerable to overuse that results in resource degradation and depletion” (Ling 2019a). |

| 4 | Based on the local practice of property rights, aside from titled CL POS, the titleship system for NT POS is quite unique as only NT POS will not be granted with any title deed, while other land uses under Native Land (e.g., house and agriculture), titles will be granted to individuals (see Section 67(1) and (2) of the SLO Cap 68). |

| 5 | Sabindo Nusantara Sdn Bhd and Anor V Majlis Perbandaran Tawau and Ors, S. 2011. 8 MLJ 653. See also Borneo Housing Mortgage Finance Berhad V Time Engineering Berhad. 1996. 2 CLJ. |

| 6 | This practice has been enforced by the Director of the Lands and Surveys Department of Kota Kinabalu (as headquarters); hence, it applies to all other districts within the State of Sabah. |

| 7 | Despite the government’s practice/house rules and conventions, which may be deemed formal, they may not be necessarily legal/de jure (following the provisions of laws) (Ling et al. 2016). |

| 8 | For each neighbourhood, 10 residents were purposively sampled. Therefore, 20 neighbourhoods from 10 zones amounted to 200 samples of respondents. This sample size is acceptable because the residents’ view is treated as a supporting or secondary role in triangulating the findings of ‘larger’ qualitative methodology (Creswell and Plano Clark 2007). Additionally, it sufficiently fulfils the study’s analysis requirements, including inferential correlations. |

| 9 | The transformative design refers to the theoretical and conceptual frameworks (e.g., property-rights theory, commons theory, social dilemmas and opportunism) that were employed to underpin this study methodology. |

| Property-Rights System | CL POS | NT POS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title-ship of POS (Issuance of title deed) | (Title deed is granted on POS) (Involving POS site handing over and POS title deed transfer) | (No title deed issuance on POS) | ||

| Status of transfer and site handing over of POS | First phase CL POS (Before title deed issuance) | Second phase CL POS (Before title deed issuance: Interim) | Third phase CL POS (Title deed issued) | Surrendered POS (State land) (Without involving site handing over/title transfer) |

| (Un-transferred title) (Un-handed over site) (Held under owner’s covenant) | (Un-transferred title) (Handed over site) (‘Bare Trustee’) ** | (Transferred title) (Handed over site) | ||

| Land ownership | Private/Common property-developer/owners | State property-Local government (As an equitable owner) | State property-Local government (As a legal owner) | State property-Local government (As an equitable owner) |

| Management regime (including monitoring, maintaining, control, etc.) | Private/Common Property-(Developer/Co-landowner(s)) (Temporary—e.g., minimum 18 months) | State property-Local Government or Local government + Common property/community association-residents (registered) * | Open-access resource (without being vested in the local council) | |

| Positions: Bundle of rights | Claimant: Only access, use and management rights are clearly and actively possessed by subdivider(s) and local government | Authorised users: Public users with use and access rights | ||

| Access | Yes | Yes | ||

| Withdrawal/use | Yes | Yes | ||

| Management | Yes | None | ||

| Exclusion | None | None | ||

| Alienation (e.g., POS disposal, title deed transfer) | The title deed is only transferable to the local council by private titleholder(s) | Not transferable | ||

| Types of Analysis | List of Items | Scale of Data |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive analysis (Frequency analysis) | 46 items from the questionnaire: | Include 3- and 5-point |

| A1-A5, B1-B3, C1-C19, D1-D16, | Likert/ordinal data, categorical | |

| E1-E2 | (dummy) data, & multiple | |

| response data | ||

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk | 27 items: C3, C8, C9, C12-C19, | Likert/ordinal data |

| (normality test) on kurtosis and skewness | D1-D14, D16 & E2 | |

| Exploratory factor analysis (Kaise-Meyer-Olkin, | 27 items: C3, C8, C9, C12-C19, | Likert/ordinal data |

| Scree plot, Bartlett’s test of sphericity) | D1-D14, D16 & E2 | |

| Cronbach Alpha (α) on two different sets of items | 18 items: C3, C8, C9, C12-C19, | Likert/ordinal data |

| after the factor analysis (Reliability test) | D1, D2, D4, D12, D14, D16, & E2 | |

| 9 items: D3, D5-D11, and D13 | ||

| Kruder-Richardson 20 (KR-20) (Reliability Test) | 21 items of B1 * and C10 | Binary/dummy responses and |

| multiple choices | ||

| 2-tailed → Spearman → rank-order → correlation | B1, C8, C9, D1-D14, D16 & E2 | Likert/ordinal data |

| (inferential/correlation) | ||

| Monte-Carlo simulation (Goodness of Fit and | e.g. between D15 and C8, & D15 | Between ordinal data and |

| Independence tests) (inferential/correlation) | and C9 | categorical data |

| Crosstabulation between nominal single response | Between C8, C9, D1, D2, D15, | Between single response |

| items and nominal multiple responses items | D16 & E2 and B1*, C2, & C11 | ordinal data & multiple |

| (inferential/correlation) | responses items |

| No. | Reasons for Not Visiting | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Poor access | 24 | 3.0 |

| 2 | Facilities and amenities shortage | 89 | 11.1 |

| 3 | Many dogs | 7 | 0.9 |

| 4 | Crowded issue | 2 | 0.2 |

| 5 | Quite and unsafe | 31 | 3.9 |

| 6 | Poorly maintained | 156 | 19.4 |

| 7 | Dirty/unhygienic | 132 | 16.4 |

| 8 | Too busy | 147 | 18.3 |

| 9 | Security issue-strangers loitering | 38 | 4.7 |

| 10 | Unattractive issue | 110 | 13.7 |

| 11 | Too far | 9 | 1.1 |

| 12 | Physically unfit | 3 | 0.4 |

| 13 | Too little shade/hot | 41 | 5.1 |

| 14 | No more park | 9 | 1.1 |

| 15 | Users’ incivility | 7 | 0.9 |

| Total | 805 | 100.0 | |

| No. | Response | Good | Fair | Poor | Undecided | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 1 | Design & Aesthetic (C12) | 16 | 8.0 | 127 | 63.5 | 56 | 28.0 | 1 | 0.5 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 2 | Cleanliness & Maintenance (C13) | 4 | 2.0 | 18 | 9.0 | 178 | 89.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 3 | Accessibility (C14) | 28 | 14.0 | 81 | 45.5 | 91 | 40.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 4 | Inclusiveness of visitors (C15) | 4 | 2.0 | 59 | 29.5 | 137 | 68.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 5 | Landscaping (C16) | 9 | 4.5 | 41 | 20.5 | 150 | 75.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 6 | Safety & Security (C17) | 20 | 10.0 | 32 | 16.0 | 148 | 74.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 7 | Diversity & Variety (C18) | 7 | 3.5 | 39 | 19.5 | 154 | 77.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 8 | Adequacy & Availability (C19) | 1 | 0.5 | 28 | 14.0 | 171 | 85.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| No. | Responses | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 1 | Inconsiderate behaviour of POS users (D1) | 11 | 5.5 | 39 | 19.5 | 150 | 75.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 2 | Poor governance and management of the government (D2) | 13 | 6.5 | 14 | 7.0 | 173 | 86.5 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 3 | Unreasonable tax imposition on residents (D4) | 21 | 10.5 | 42 | 21.0 | 137 | 68.5 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 4 | Constant uncivilised users lead to worse POS quality (D12) | 5 | 2.5 | 11 | 5.5 | 184 | 92.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 5 | The current practice is burdening for a landowner (D14) | 1 | 0.5 | 23 | 11.5 | 176 | 88.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 6 | Exclusionary is better than unexclusionary POS (D16) | 2 | 1.0 | 28 | 14.0 | 170 | 85.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 7 | Self-governing collective action is better (E2) | 1 | 0.5 | 12 | 6.0 | 187 | 93.5 | 200 | 100.0 |

| No. | Response | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 1 | Defective behaviour is triggered by the government; users cause poor POS (D3) | 3 | 1.5 | 61 | 30.5 | 131 | 68.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 2 | User may shirk if others shirk, e.g., paying rating tax (D5) | 2 | 1.0 | 22 | 11.0 | 176 | 88.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 3 | Squatters or outsiders create utilisation and quality issue (D6) | 5 | 2.5 | 11 | 5.5 | 184 | 92.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 4 | Unspecified “when and what time” on consumption may lead to quality issue (D7) | 17 | 8.5 | 31 | 15.5 | 152 | 76.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 5 | Unspecified “how” on consumption may lead to quality issue (D8) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.0 | 196 | 98.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 6 | Unspecified “who and what age/ how old” may lead to quality issue (D9) | 27 | 13.5 | 57 | 28.5 | 116 | 58.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 7 | Unspecified “contingency” (e.g., no prior notice) may lead to quality issue (D10) | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 5.5 | 189 | 94.5 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 8 | Users do not have an incentive to use responsibly or protect POS (D11) | 9 | 4.5 | 12 | 6.0 | 179 | 89.5 | 200 | 100.0 |

| 9 | Users no incentive or right to care/ monitor users’ POS consumption behaviour (D13) | 4 | 2.0 | 14 | 7.0 | 182 | 91.0 | 200 | 100.0 |

| B1 | C8 | C9 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D9 | D10 | D11 | D12 | D13 | D14 | D16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| C8 | −0.346 ** | |||||||||||||||||

| C9 | −0.185 ** | 0.587 ** | ||||||||||||||||

| D1 | −0.094 | 0.398 ** | 0.417 ** | |||||||||||||||

| D2 | −0.112 | 0.357 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.567 ** | ||||||||||||||

| D3 | 0.261 ** | −0.025 | 0.038 | 0.618 * | 0.171 | |||||||||||||

| D4 | −0.187 ** | 0.522 ** | 0.332 ** | 0.257 ** | 0.371 ** | −0.014 | ||||||||||||

| D5 | −0.013 | −0.002 | 0.119 | 0.092 | 0.028 | 0.147 * | −0.018 | |||||||||||

| D6 | 0.281 ** | −0.259 ** | −0.003 | 0.004 | −0.034 | 0.200 ** | −0.082 | 0.256 ** | ||||||||||

| D7 | 0.086 | −0.102 | −0.012 | 0.046 | −0.058 | 0.235 ** | −0.128 | 0.186 ** | 0.080 | |||||||||

| D8 | 0.161 * | 0.064 | 0.247 ** | 0.178 * | 0.116 | 0.369 ** | 0.017 | 0.220 ** | 0.156 * | 0.333 ** | ||||||||

| D9 | 0.267 ** | −0.196 ** | −0.057 | −0.007 | −0.098 | 0.119 | −0.069 | 0.012 | 0.233 ** | 0.252 ** | 0.208 ** | |||||||

| D10 | 0.054 | 0.065 | −0.017 | −0.093 | −0.017 | −0.019 | −0.011 | −0.090 | −0.132 | 0.010 | −0.034 | 0.024 | ||||||

| D11 | −0.006 | 0.152 * | 0.180 * | 0.096 | 0.06 | 0.021 | −0.062 | 0.146 * | −0.104 | 0.074 | 0.048 | 0.006 | 0.117 | |||||

| D12 | 0.040 | 0.036 | −0.003 | −0.122 | −0.065 | −0.017 | 0.013 | −0.008 | −0.306 ** | 0.113 | 0.116 | −0.054 | 0.201 ** | 0.223 * | ||||

| D13 | 0.068 | 0.041 | 0.074 | −0.075 | 0.050 | 0.124 | −0.013 | −0.136 | −0.055 | 0.186 ** | 0.030 | 0.086 | 0.129 | 0.247 ** | 0.062 | |||

| D14 | 0.019 | 0.12 | 0.053 | 0.034 | 0.001 | 0.110 | −0.005 | 0.011 | −0.094 | 0.137 | −0.047 | 0.038 | 0.204 ** | −0.054 | 0.118 | 0.072 | ||

| D16 | 0.113 | −0.004 | −0.015 | 0.058 | 0.022 | 0.114 | −0.047 | −0.099 | 0.075 | 0.048 | 0.161 * | 0.127 | −0.091 | −0.045 | −0.015 | 0.071 | 0.076 | |

| E2 | 0.032 | 0.026 | 0.078 | 0.119 | −0.046 | 0.152 * | −0.082 | −0.056 | −0.055 | 0.220 ** | 0.227 ** | 0.132 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.039 | 0.04 | 0.136 | 0.215 ** |

| No. | Variables | Chi-Square | DF | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nearby POS quality (C8) | 38.29 * | 9 | 0.00 |

| 2 | User’s defective behaviour in consumption (D1) | 26.44 * | 9 | 0.00 |

| 3 | Government’s inefficient governance (D2) | 26.23 * | 9 | 0.01 |

| 4 | Users may not monitor and intervene in other users’ defective behaviour (D12) | 4.24 | 9 | 0.83 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ling, G.H.T.; Leng, P.C.; Ho, C.S. Effects of Diverse Property Rights on Rural Neighbourhood Public Open Space (POS) Governance: Evidence from Sabah, Malaysia. Economies 2019, 7, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7020061

Ling GHT, Leng PC, Ho CS. Effects of Diverse Property Rights on Rural Neighbourhood Public Open Space (POS) Governance: Evidence from Sabah, Malaysia. Economies. 2019; 7(2):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7020061

Chicago/Turabian StyleLing, Gabriel Hoh Teck, Pau Chung Leng, and Chin Siong Ho. 2019. "Effects of Diverse Property Rights on Rural Neighbourhood Public Open Space (POS) Governance: Evidence from Sabah, Malaysia" Economies 7, no. 2: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7020061

APA StyleLing, G. H. T., Leng, P. C., & Ho, C. S. (2019). Effects of Diverse Property Rights on Rural Neighbourhood Public Open Space (POS) Governance: Evidence from Sabah, Malaysia. Economies, 7(2), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7020061