Impact of Multilateral Trade Liberalization on Resource Revenue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Discussion on the Theoretical Impact of Multilateral Trade Liberalization on Resource Revenue

3. Measurement of Domestic and Multilateral Trade Policy

4. Model Specification and Estimation Strategy

4.1. Model Specification

4.2. Estimation Strategy

5. Interpretation of Empirical Results

6. Further Analysis: Does the Effect of Multilateral Trade Liberalization on Resource Revenue Depend on the Degree of Domestic Trade Policy Liberalization?

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| RESREV | This is the total resource revenue, % GDP. It is the total natural resource revenues, including natural resource revenues reported as “tax revenue” or “non-tax revenue”. Natural resources are defined here as natural resources that include a significant component of economic rent, primarily from oil and mining activities. | ICTD Public revenue Dataset. See online: http://www.ictd.ac/datasets/the-ictd-government-revenue-dataset |

| NONRESREV | This is the measure of non-resource revenue, in % GDP. It is the difference between total public revenue and resource revenue, both expressed, in % GDP. | Authors’ calculation. Data on both total public revenue and resource revenue are extracted from the ICTD: ICTD Public revenue Dataset. See online: http://www.ictd.ac/datasets/the-ictd-government-revenue-dataset |

| DTP | This is the domestic trade policy. It is measured by the index of “freedom to trade internationally”, which is an important component of the Economic Freedom Index. It is a composite measure of the absence of tariff and non-tariff barriers that affect imports and exports of goods and services. Its computation is based on two components: trade-weighted average tariff rage and non-tariff barriers (NTBs), the extent of latter having been determined on the basis of quantitative and qualitative available information. NTBs include quantity restrictions, price restrictions, regulatory restrictions, investment restrictions, customs restrictions, and direct government interventions. This score is graded on a scale of 0 to 100, with a rise indicating lower trade barriers, i.e., higher trade liberalization, while a decrease in this index reflects rising trade protectionism. | Heritage Foundation (see Miller et al. 2017) |

| MTP | Average trade policy of the rest of the world. For a given country, this variable has been calculated as the average DTP score of the rest of the world (i.e., for all other countries, except for the one for which the variable is being calculated). | Author’s calculation based on Heritage Foundation data. |

| GDPC | GDP per capita (constant 2010 US$) | WDI |

| INF | Inflation rate (%) | WDI |

| POP | Total population | WDI |

| OILPR | These are the oil prices, in US Dollars, deflated by the Index of United States’ Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers. | Data on both the oil prices and the US consumer price index are extracted from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (see online at: https://fred.stlouisfed.org) |

| INST | This is the variable capturing institutional quality in a given country. It has been computed by extracting the first principal component (based on factor analysis) of the following six indicators of governance. These indicators include an index of political stability and absence of violence/terrorism; an index of regulatory quality; an index of rule of law; an index of government effectiveness; an index of Voice and Accountability; and an index of corruption.It is worth noting that higher values of the index “INST” are associated with better governance and institutional quality, while lower values reflect worse governance and institutional quality. | Data on the components of “INST” variable has been extracted from World Bank Governance Indicators developed by Kaufmann et al. (2010) and recently updated. |

| Entire Sample | LDCs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | Indonesia | Qatar | Angola |

| Angola | Iran, Islamic Rep. | Russian Federation | Burkina Faso |

| Azerbaijan | Israel | Sao Tome and Principe | Chad |

| Bahrain | Jamaica | Saudi Arabia | Equatorial Guinea |

| Bolivia | Kazakhstan | Senegal | Guinea |

| Botswana | Kuwait | Serbia | Lao PDR |

| Brunei Darussalam | Lao PDR | Sierra Leone | Liberia |

| Burkina Faso | Liberia | Sudan | Mauritania |

| Cameroon | Libya | Suriname | Niger |

| Chad | Malaysia | Timor-Leste | Sao Tome and Principe |

| Chile | Mauritania | Togo | Senegal |

| Colombia | Mexico | Trinidad and Tobago | Sierra Leone |

| Congo, Rep. | Moldova | Tunisia | Sudan |

| Cote d’Ivoire | Mongolia | Uganda | Timor-Leste |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | Namibia | Venezuela, RB | Togo |

| Equatorial Guinea | Niger | Vietnam | Uganda |

| Gabon | Nigeria | Yemen, Rep. | Yemen, Rep. |

| Ghana | Norway | Zambia | Zambia |

| Guinea | Papua New Guinea | Zimbabwe | |

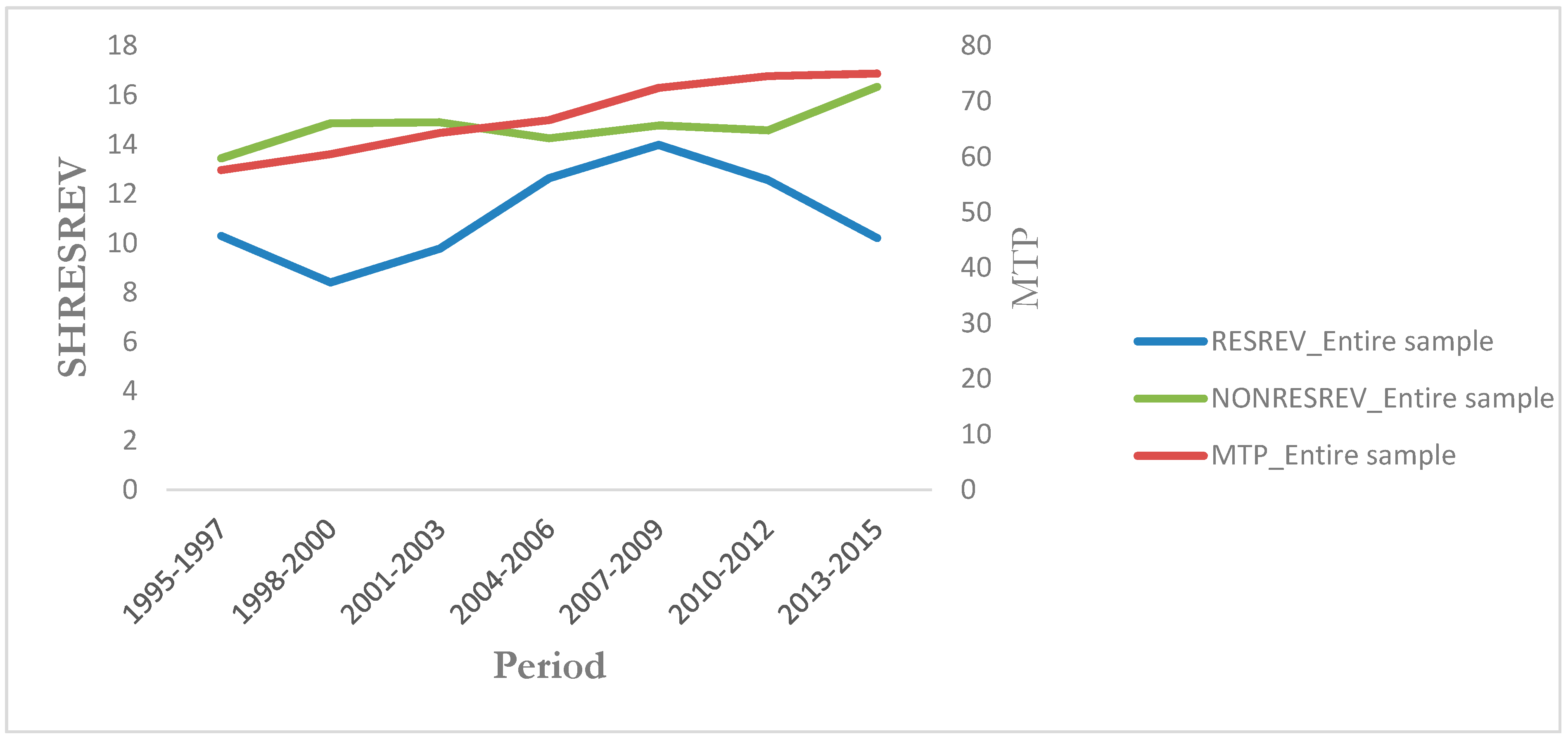

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESREV | 328 | 11.225 | 12.851 | 0.000 | 63.204 |

| MTP | 399 | 67.252 | 6.417 | 57.363 | 75.102 |

| DTP | 368 | 63.723 | 14.494 | 19.733 | 89.300 |

| NONRESREV | 326 | 14.781 | 7.571 | 1.742 | 36.833 |

| GDPC | 394 | 8434.716 | 15,361.140 | 157.565 | 90,204.810 |

| INF | 390 | 81.415 | 1241.282 | −6.934 | 24,411.030 |

| INST | 397 | −1.104 | 1.661 | −4.794 | 4.412 |

| OILPR | 399 | 0.262 | 0.126 | 0.117 | 0.449 |

| POP | 399 | 2.44 × 107 | 4.20 × 107 | 127,916.7 | 2.54 × 108 |

References

- Agbeyegbe, Terence, Janet Gale Stotsky, and Asegedech WoldeMariam. 2006. Trade Liberalisation, Exchange Rate Changes and Tax Revenue in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Asian Economics 17: 261–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., and S. Bond. 1991. Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations. Review of Economic Studies 58: 277–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevêdo, R. 2015. Information Technology Agreement press conference: Remarks by Director-General Roberto Azevêdo. December 16. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/spra_e/spra104_e.htm (accessed on 23 May 2017).

- Baunsgaard, Thomas, and Michael Keen. 2010. Tax Revenue and (or?) Trade Liberalization. Journal of Public Economics 94: 563–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Richard M., Jorge Martinez-Vazquez, and Benno Torgler. 2008. Tax Effort in Developing Countries and High Income Countries: The Impact of Corruption, Voice and Accountability. Economic Analysis and Policy 38: 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial Conditions and Moment Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, Jean-François, Gerard Chambas, and Samuel Guerineau. 2007. Aide et mobilisation fiscale dans les pays en développement. AFD Jumbo, Rapport Thématique. 21. Paris: Agence Française de Développement (AfD) Département de la Recherch. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, J.-F., G. Chambas, and B. Laporte. 2011. IMF Programs and Tax Effort What Role for Institutions in Africa? CERDI Etudes et Documents. 2010.33. Clermont-Ferrand: CERDI, Université d’Auvergne. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, Jean-François, Gerard Chambas, and Mario Mansour. 2015. Tax Effort of Developing Countries: An Alternative Measure. In Financing Sustainable Development Addressing Vulnerabilities. Edited by Matthieu Boussichas and Patrick Guillaumont. Paris: Fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international (FERDI) in association with Éditions Economica, chp. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, Bonnie G., Quan V. Le, and Meenakshi Rishi. 2012. Foreign direct investment and institutional quality: Some empirical evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis 21: 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, Avik. 2001. The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investments: Sensitivity Analyses of Cross-Country Regressions. Kyklos 54: 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelliah, Raja J. 1971. Trends in Taxation in Developing Countries. IMF Staff Papers 18: 254–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Changkyu, and Myung Hoon Yi. 2009. The effect of the internet on economic growth: Evidence from cross-country panel data. Economic Letters 105: 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clist, Paul. 2016. Foreign aid and domestic taxation: Multiple sources, one conclusion. Development Policy Review 34: 365–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clist, Paul, and Oliver Morrissey. 2011. Aid and Tax Revenue: Signs of a Positive Effect since the 1980s. Journal of International Development 23: 165–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, David R. 2011. Multilateral Trade, Foreign Direct Investment and the Volume of World Trade. Economics Letters 113: 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivelli, Ernesto, and Sanjeev Gupta. 2014. Resource Blessing, Revenue Curse? Domestic Revenue Effort in Resource-Rich Countries. European Journal of Political Economy 35: 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabla-Norris, Era Camelia Minoiu, and Luis-Felipe Zanna. 2015. Business Cycle Fluctuations, Large Macroeconomic Shocks, and Development Aid. World Development 69: 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollar, David. 1992. Outward-Oriented Developing Economies Really Do Grow More Rapidly: Evidence from 95 LDCs, 1976–85. Economic Development and Cultural Change 40: 523–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, John C., and Aart C. Kraay. 1998. Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimation with Spatially Dependent Panel Data. Review of Economics and Statistics 80: 549–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrill, Liam, Janet Stotsky, and Reint Gropp. 1999. Revenue Implications of Trade Liberalization. IMF Occasional Paper 99/80 International Monetary Fund. Washington: IMF. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, Peter, Mario Larch, and Michael Pfaffermay. 2004. Multilateral trade and investment liberalization: effects on welfare and GDP per capita convergence. Economics Letters 84: 133–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghura, Dhaneshwar. 1998. Tax Revenue in Sub-Sahara Africa: Effects of Economic Policies and Corruption. WP/98/135. Washington: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Globerman, Steven, and Daniel Shapiro. 2002. Global foreign direct investment flows: the role of governance infrastructure. World Development 30: 1899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2017a. Multilateral Trade Liberalization and Foreign Direct Investment Inflows. Economics Affairs 37: 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2017b. The Impact of Multilateral Trade Liberalization on Economic Development: Some Empirical Evidence. Economic Affairs 37: 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2017c. Effect of multilateral trade liberalization on foreign direct investment outflows amid structural economic vulnerability in developing countries. Research in International Business and Finance 45: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2017d. Multilateral Trade Liberalization and Public revenue. Journal of Economic Integration 32: 586–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2017e. Multilateral Trade Liberalization, Export Share in the International Trade Market and Aid for Trade. Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy 08: 1750014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2018a. Impact of multilateral trade liberalization and aid for trade for productive capacity building on export revenue instability. Economic Analysis and Policy 58: 141–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2018b. Multilateral Trade Liberalization and Economic Growth. Journal of Economic Integration 33: 1261–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm, and Jean-François Brun. 2017. Impact of export upgrading on tax revenue in developing and high-income countries. Oxford Development Studies 45: 542–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2010. The Worldwide Governance Indicators Methodology and Analytical Issues, World Bank Policy Research N° 5430 (WPS5430). Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Khattry, Barsha, and Mohan J. Rao. 2002. Fiscal Faux Pas?: An analysis of the revenue implications of trade liberalization. World Development 30: 1431–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Terry, Anthony B. Kim, James M. Roberts, Bryan Riley, and Tori Whiting. 2017. 2017 Index of Economic Freedom, Institute for Economic Freedom, The Heritage Foundation, Washington, DC. Available online: http://www.heritage.org/index/download (accessed on 23 November 2016).

- Morrissey, Oliver. 2015. Aid and Government Fiscal Behavior: Assessing Recent Evidence. World Development 69: 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, Oliver, Christian Von Haldenwang, Armin Von Schiller, Maksym Ivanyna, and Ingo Bordon. 2016. Tax Revenue Performance and Vulnerability in Developing Countries. Journal of Development Studies 52: 1689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, S. 1981. Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects. Econometrica 49: 1417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omgba, Luc Désiré. 2016. On the Mobilization of Domestic Resources in Oil Countries: The Role of Historical Factors. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2016/154. Helsinki, Finland: UNU-WIDER. [Google Scholar]

- Paunov, Caroline, and Valentina Rollo. 2016. Has the Internet Fostered Inclusive Innovation in the Developing World? World Development 78: 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnaike, Yasanji C. 2012. Is there an empirical link between trade liberalisation and export performance? Economics Letters 117: 375–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, David. 2009. A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bulletin of Economic and Statistics 71: 135–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, Jeffrey. D., and Andrew Warner. 1995. Economic Reform and the Process of Global Integration. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 26: 1–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Friedrich, and Bruno S. Frey. 1985. Economic and political determinants of foreign direct investment. World Development 13: 161–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, Vito. 1977. Inflation, Lags in Collection, and the Real Value of Tax Revenue. Staff Papers. International Monetary Fund 26: 154–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Alun H., and Juan P. Treviño. 2013. Resource Dependence and Fiscal Effort in Sub-Saharan Africa. IMF Working Paper, WP/13/188. Washington, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2017. International Trade and Development. Report of the Secretary-General of UNCTAD Prepared for the UNCTAD’s Seventy-Second Session, Document A/72/274. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Von Haldenwang, Christian, and Maksym Ivanyna. 2017. Does the Political Resource Curse Affect Public Finance? The Vulnerability of Tax Revenue in Resource-Rich Countries. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2017/7. Helsinki, Filand: UNU-WIDER. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, David, and Ashoka Mody. 1992. International investment location decisions: the case of US firms. Journal of International Economics 33: 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windmeijer, Frank. 2005. A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. Journal of Econometrics 126: 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeyati, EduardoLevy, Ugo Panizza, and Ernesto Stein. 2007. The cyclical nature of North-South FDI flows. Journal of International Money and Finance 26: 104–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohou, Hermann D., Michaël Goujon, and Wautabouna Ouattara. 2016. Heterogeneous Aid Effects on Tax Revenues: Accounting for Government Stability in WAEMU Countries. Journal of African Economies 25: 468–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The objective of the ITA is to eliminate imports duties on information technology products covered by the agreement. The latter was the first and most significant tariff liberalisation arrangement negotiated in the WTO since its establishment in 1995. At the Nairobi Ministerial Conference in December 2015, over 50 members concluded the expansion of the agreement (see detailed information on the WTO’s website https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/inftec_e/inftec_e.htm, accessed 23 May 2017). Under the present plan, around 65% of tariffs lines would be eliminated in 2016 (accounting for around 88% of imports). By 2019, 89% of the tariff lines will be eliminated (representing 95% of imports). This will reach 100% over seven years (see Azevêdo 2015). |

| 2 | Multilateral trade liberalization could particularly encourage policymakers, including those in resource dependent countries to devise public policies in favour of export product diversification (away from natural resource exports toward higher value-added export products). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | A number of empirical studies (Schneider and Frey 1985; Wheeler and Mody 1992; Chakrabarti 2001) have underlined the relevance of the population size (measure of the host-country’s market size) for FDI inflows. |

| 5 | Further information on LDCs is provided by the United Nations office of the high representative for the least developed countries, landlocked developing countries and small island developing states. See online at: http://unohrlls.org/about-ldcs/. |

| 6 | The Aid for Trade Initiative of the World Trade Organization (WTO) aims to build trade capacity in developing countries, and particularly LDCs. |

| FE-DK | Two-Step System GMM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Log(RESREV) | Log(RESREV) | Log(RESREV) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Log(RESREV)t−1 | 0.804 *** | 0.701 *** | |

| (0.0462) | (0.0480) | ||

| MTP | −0.00674 | −0.0372 *** | −0.0338 *** |

| (0.0111) | (0.00561) | (0.00749) | |

| LDC*MTP | 0.0378 *** | ||

| (0.00783) | |||

| LDC | −2.886 *** | ||

| (0.547) | |||

| NONRESREV | −0.0467 *** | −0.0546 *** | −0.0728 *** |

| (0.00662) | (0.00665) | (0.00837) | |

| Log(GDPC) | 0.287 *** | 0.119 *** | 0.160 *** |

| (0.0467) | (0.0377) | (0.0527) | |

| Log(INF) | 0.0313 ** | −0.0330 ** | −0.00901 |

| (0.0137) | (0.0134) | (0.0156) | |

| DTP | 0.00329 ** | 0.0170 *** | 0.0106 *** |

| (0.00125) | (0.00309) | (0.00391) | |

| Log(POP) | −0.145 | −0.0194 | −0.0397 |

| (0.129) | (0.0308) | (0.0342) | |

| OILPR | 1.192 *** | 0.293 | 0.281 |

| (0.339) | (0.204) | (0.221) | |

| INST | 0.0625 | −0.0525 | −0.0401 |

| (0.0488) | (0.0331) | (0.0354) | |

| Constant | 2.516 * | 1.944 *** | 2.658 *** |

| (1.441) | (0.350) | (0.495) | |

| Observations-Countries | 300-57 | 253-57 | 253-57 |

| Within R-squared | 0.3201 | ||

| Number of Instruments | 46 | 47 | |

| AR1 (P-Value) | 0.0048 | 0.0074 | |

| AR2 (P-Value) | 0.3908 | 0.6626 | |

| AR3 (P-Value) | 0.5880 | 0.3614 | |

| Sargan (P-Value) | 0.3898 | 0.3358 | |

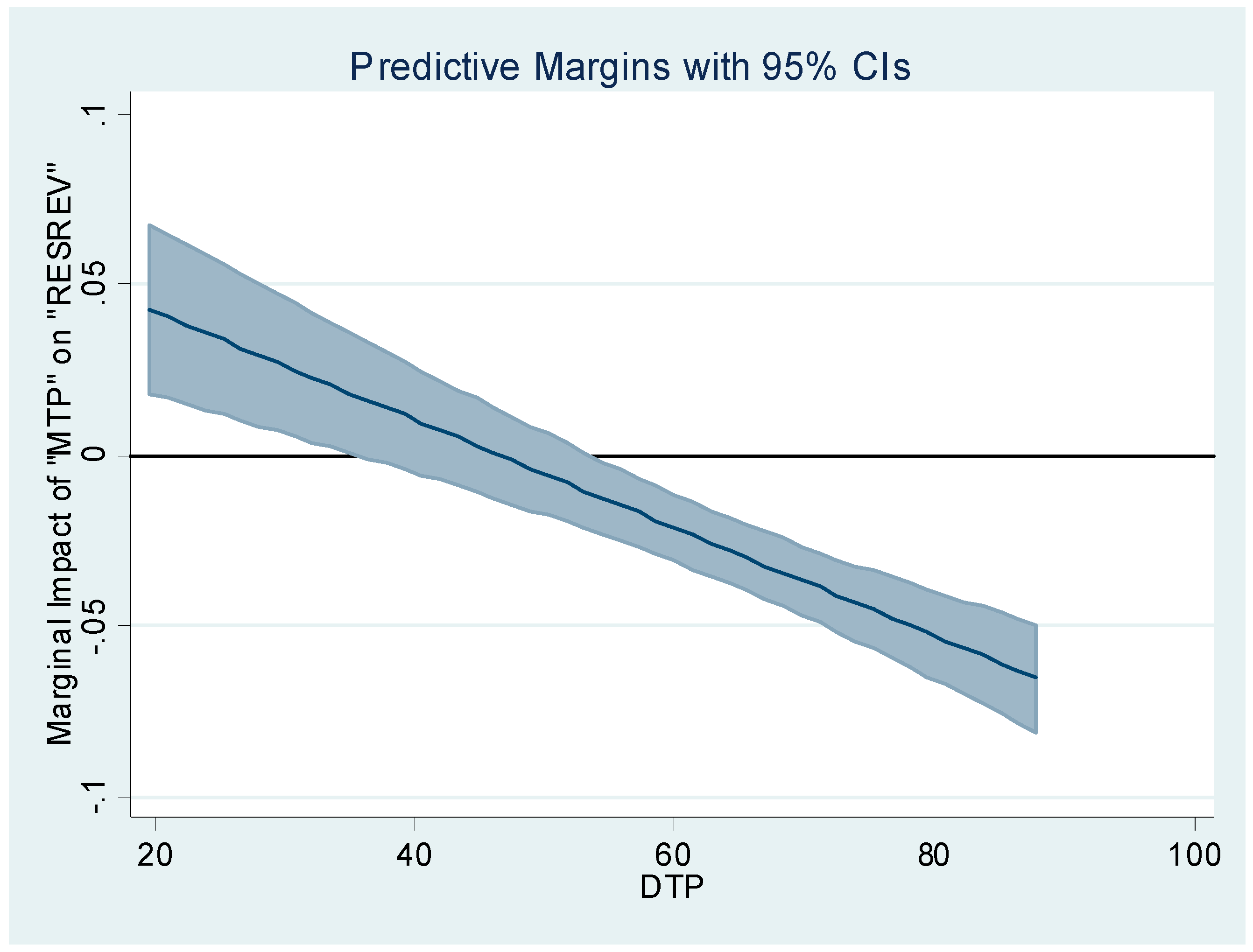

| VARIABLES | Log(RESREV) |

|---|---|

| (1) | |

| Log(RESREV)t−1 | 0.809 *** |

| (0.0473) | |

| MTP | 0.0736 *** |

| (0.0174) | |

| DTP*MTP | −0.00158 *** |

| (0.000262) | |

| NONRESREV | −0.0632 *** |

| (0.00639) | |

| Log(GDPC) | 0.114 ** |

| (0.0461) | |

| Log(INF) | −0.0641 *** |

| (0.0228) | |

| DTP | 0.113 *** |

| (0.0168) | |

| Log(POP) | 0.0249 |

| (0.0253) | |

| OILPR | 0.590 *** |

| (0.145) | |

| INST | −0.00192 |

| (0.0263) | |

| Constant | −5.340 *** |

| (1.164) | |

| Observations-Countries | 253-57 |

| Within R-squared | |

| Number of Instruments | 47 |

| AR1 (P-Value) | 0.0074 |

| AR2 (P-Value) | 0.7695 |

| AR3 (P-Value) | 0.7137 |

| Sargan (P-Value) | 0.2469 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gnangnon, S.K.; Brun, J.-F. Impact of Multilateral Trade Liberalization on Resource Revenue. Economies 2018, 6, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies6040060

Gnangnon SK, Brun J-F. Impact of Multilateral Trade Liberalization on Resource Revenue. Economies. 2018; 6(4):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies6040060

Chicago/Turabian StyleGnangnon, Sena Kimm, and Jean-François Brun. 2018. "Impact of Multilateral Trade Liberalization on Resource Revenue" Economies 6, no. 4: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies6040060

APA StyleGnangnon, S. K., & Brun, J.-F. (2018). Impact of Multilateral Trade Liberalization on Resource Revenue. Economies, 6(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies6040060