Abstract

The implementation of environmental taxation is one of the most important issues of environmental policy in Europe. To approach this matter, the paper aims to analyse the determinants of environmental taxation revenue for European countries. Besides investigating the most explored determinants, such as those related to production, consumption and environmental quality, particular attention is paid to some non-trivial factors. Firstly, we analyse the importance of the institutional context that is crucial for policy enforcement. Secondly, we consider the consumption of rapidly obsolescent goods, such as information and communication technology (ICT) goods characterised by intensive waste generation. Finally, the importation of final goods as a consequence of production offshoring is taken into account. The results demonstrate that the above-mentioned determinants have a heterogeneous impact on environmental taxation revenue in EU Western countries and EU Eastern countries, which can be due to a still weak institutional context of the latter economies and their peculiar patterns of development.

JEL Classification:

F18; H23; O10; Q58

1. Introduction

Environmental taxation (ET) is one of the most widespread environmental policy instruments in Europe and has been introduced gradually in member states from the early nineties, as a response to increasing environmental degradation. Its effectiveness is recorded by numerous studies that demonstrate the positive impact of taxation on environmental quality (EEA 2005; Ekins and Barker 2001; Scrimgeour et al. 2005). At the same time, ET is argued to have another important impact that regards economic performance. This was incentivised through the Environmental Tax Reform (European Commission 1997) that shifts the tax burden “from economic function, sometimes called ‘goods’, such as labour (personal income tax), capital (corporate income tax) and consumption (VAT and other indirect taxes), to activities that lead to environmental pressures and over use of natural resources, sometimes called ‘bads’” (EEA 2005, p. 83). The importance of this is evident since it recognises ET as an instrument that seeks to reconcile economic growth with the environment. Despite the evidence on the importance of ET for the environment and economic performance, there has been little work that delineates the determinants of ET itself. Yet the identification of the range of factors that influence ET is important for the application, functioning and monitoring of the overall taxation system. This paper aims to fill these lacunae by analysing the determinants of environmental taxation revenue in EU Western countries and EU Eastern countries, over the period 1996–2011.

The present study contributes to existing literature on environmental taxation in several ways. Firstly, in addition to the most expected and known factors that influence ET, such as the energy intensity of the economy and environmental quality, we investigate the incidence on environmental taxation of some non-trivial, significant factors. These are the institutional context, the consumption of information and communication technology (ICT) goods and economic openness, expressed by rule of law, imports of ICT goods and other imports (i.e., total imports of goods and services except ICT). Secondly, in capturing the greening of the taxation system we take into account various indicators of the environmentally related tax revenue. These indicators permit us to capture the environmental taxation burden reflecting the effectiveness of environmental policy. Finally, we explore the heterogeneity of environmental taxation in European countries, both EU Western and Eastern countries, as a result of the different paths that these economies have followed in their institutional and economic development.

Our findings highlight the importance of both explored and not explored factors in determining environmental taxation revenue. For EU Western countries, the rule of law is found to be decisive for the enforcement of environmental taxation. For these economies, the consumption of information and communication technology goods augments the ET revenue since it increases technological waste due to the higher rate of technology obsolescence. On the other side, the results demonstrate that ET revenue decreases as other imports increase, as a consequence of the offshoring process of domestic production, thus shifting the pollution source abroad. We find that these results do not hold for EU Eastern countries probably due to their still weak institutional context and the higher energy intensity of their production sectors.

2. Background

2.1. Environmental Taxation and Economic Growth

Environmental taxation is one of the instruments that policymakers introduce to compel private users of environmental goods to take into account the social costs of their actions. Moreover, ET has played an important role in policy debates, as it is considered that raising environmental taxes could create scope for tax cuts in other areas and thus deliver a double dividend by boosting employment and improving the quality of the environment at the same time (Eurostat 2013). Although some papers offer support for the existence of a double dividend (Bento and Jacobsen 2007; Taheripour et al. 2008), whilst others provide mixed support (Takeda 2007) or no support (Bovenberg et al. 2008; Williams 2002), both arguments (positive effects on employment and environment) are at the base of the Environmental Tax Reform in the European Union as proposed by the European Environmental Agency (EEA 2005). According to this reform the ET may provide a double dividend since shifting from conventional to environmental taxation, under certain conditions (discussed by (Fullerton and Metcalf 1997; Goulder 2013; Kampas and Horan 2016)), not only corrects a negative externality, but also reduces distorting effects of taxation in other markets, thereby improving welfare (Ekins et al. 2011). Recent literature explores the presence of different dividends in environmental taxation. A third dividend may accrue from growth effect or fiscal consolidation. Karydas and Zhang (2017) present a theoretical model that allows to identify the sufficient conditions for higher growth after an ETR. They find that the results of an environmental tax reform on economic growth are ambiguous. In the Swiss case, they show that a growth dividend in the long-run exists when revenue from taxes on emissions are used to replace taxes on capital. Yamazaky (2017) provides evidence on how a revenue-neutral carbon tax may not adversely affect employment. Pereira and Pereira (2017) show, for the case of Portugal, that it is possible to design a revenue-neutral tax reform that yields three dividends, reaching environment, employment and budgetary positive effects.

According to Sterner and Köhlin (2003), the need for common environmental regulation within the European Union has been one of the major justifications for greater harmonisation between countries. This argument has also been used to persuade sceptics about EU enlargement. In fact, there was a fear that the entry of new countries could also worsen the EU environment as a whole, since the former socialist countries had toothless environmental taxes and slack regulations. Bluffstone (2003), reports that in these planned economies the purpose of such taxes was to create incentives for state enterprises to reduce pollution and at the same time raise revenues for environmental investments. In practice, however, while transiting to market economies, these countries chose a very light fiscal regime that conflicted with the adoption and enforcement of a common environmental taxation policy.

While the results of ET implementation are well documented in empirical studies, the factors that contribute to its performance are often left in the shade. A few studies make an effort to analyse the ET policy instruments and identify factors crucial for its efficacy (Anger et al. 2006; Bovenberg and de Mooij 1997; Castiglione et al. 2014; Ekins and Barker 2001; Muller and Sterner 2006; Ward and Cao 2012). In the light of these studies, the most explored determinants of ET can be identified. The first is usually called “bads” and can be classified in the following broad categories: energy, transport, pollution and resources (Kosonen 2010). The “bads” are clearly related to any activity of either production and consumption processes that create pollution and may be referred to different indicators, such as energy intensity of the economy, manufacturing production, waste creation or emission levels.

Regarding the “bads”, we should refer to the recent discussion on the relationship between economic development and the environmental quality. Most of the studies in this field demonstrate the existence of an Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) that links economic growth and the environment (e.g., Baek et al. 2009; Castiglione et al. 2012; Costantini and Martini 2010; Dutt 2009; Lipford and Yandle 2010; Markandya et al. 2006). The theory suggests that economic growth and economic welfare are inter-connected, and environmental protection policy can be seen as a consequence but also as a driver of economic development, since environmental regulation can stimulate innovation that reduces the costs of complying with it (Porter and van der Linde 1995).

2.2. Rule of Law, ICT and Importation

The goal of combining economic growth and environmental quality is achieved by the application of effective environmental policies. The decisive factor for ET is the quality of governance, and, therefore, the capacity of the state to manage the taxation system. Obviously, the quality of governance is closely related to its enforcement. Institutions such as property rights, legal origins, and democracy have been shown to have an important impact on environmental quality and policy (Cole 2007; Damania et al. 2003; Pellegrini and Gerlagh 2006) and, consequently, on ET (Castiglione et al. 2014). From the environmental perspective, the institution of the rule of law is of major importance since it reflects the supremacy of law and the quality of the institutional context itself. Institutional enforcement, and particularly that of the rule of law, should define the capacity of the state to impose, collect and monitor taxes in general, and in particular environmental taxes. Consequently, the degree of heterogeneity of the rule of law enforcement among countries is expected to influence differently the efficiency of environmental policies. In developing or former transition countries, the weakness of the rule of law may undermine the application of environmental taxes. In fact, Bluffstone (2003) highlights the differences between groups of countries as regards ET reporting that economies with lower levels of income have less developed regulatory bureaucracies and less efficient monitoring systems. Bluffstone (2003) makes an example of weak inspections of polluting industries in Bulgaria, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. The links between the rule of law and effective environmental policies are also underlined in Bhattarai and Hammig (2001), Ivanova (2010) and Panayotou (1997).

Another important but controversial factor determining ET can be considered the economic openness of a country. As demonstrated by Baek et al. (2009), economic openness, economic development and environmental quality are interdependent. The empirical and theoretical research that considers this dependency covers a wide range of factors, among which are pollution havens, EKC and the ET double dividend. For developed countries, economic openness has certain features that should be considered in our analysis. One of the features is the transfer of industrial production to developing economies. This refers, from an environmental perspective, to a problem of interaction of developed and developing economies, discussed by Davis (2003) and, particularly, to the exporting of pollution and importing of final goods for consumption (Al-mulali and Sheau-Ting 2014) by developed economies. Given the evident reduction of home manufacturing of these countries, their total ET revenue decreases in tandem with the increase of imports.

It seems important to shed light on the current process of the offshoring of production. A process that, although leading to the decrease of ET revenues, in developed countries may not be always a sign of a better environmental performance. The pollution reduction may lead to the consideration of countries as virtuous ones, but it can also be a sign of pollution export, which is a less virtuous behaviour. Understanding the situation across European countries would contribute to installing a less distorted policy of environmental renaissance at a global level.

It should be noted that the same process of transferring the production process abroad has an opposite effect on ET revenue, if we consider goods consumption that implies the generation of a high amount of waste. One example is ICT goods that have the particular characteristics of rapid obsolescence and fast rate of substitution (around 25–50%, as argued by (Parisi et al. 2002)). ICTs have received increased attention from economists over the past decades. Most of the studies recognise the importance of these technologies in determining firm productivity (Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1996; Hall et al. 2013) firm efficiency (Becchetti et al. 2003; Castiglione 2012) and overall economic growth (Gordon 2002; Infante and Smirnova 2016; Warr and Ayres 2012). However, nowadays, continuously evolving technological change tends to encourage well-off consumers to look for newer versions, shortening the replacement cycle, even though the product is still working. Devices such as mobile phones, tablets, computers and television sets in developed economies are continuously displaced by new applications that render the use of the “old” models unsatisfactory and hence leading to their replacement with technologically superior ones.

It is interesting to note that ICTs were introduced, during the seventies and eighties, as energy saving devices to reduce the depletion of natural resources that were used in production (such as oil, iron and other raw materials). Instead, nowadays ICTs have become a significant source of pollution. In the OECD Environmental Outlook to 2030 (OECD 2008), it is reported that the e-waste from end-of-life electric and electronic appliances is creating an increasingly important management challenge in both developed and developing countries.

This phenomenon, as argued by Tong et al. (2012), is also the result of the so-called built-in “planned-obsolescence” since product design itself promotes rapid consumption. Considering the fact that ICT consumption increases with the number of users, the process of substitution of obsolete products involves a growing number of consumers. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (2012), given the increasing “market penetration” in developing countries, “replacement market” in developed countries and “high obsolescence rate”, the problem of e-waste should be urgently addressed. European Union members in 2002 made the attempt to restrict the use of harmful substances in electric and electronic products (European Commission 2007) through two Directives targeting e-waste recycling, the Directive on Waste Electric and Electronic Equipment and the Directive on the Restriction of the Use of Certain Hazardous Substances in Electric and Electronic Equipment. However, as Tong et al. (2012) stress, complying with such policies is a rather complex and long drawn out process that requires enforcement and cooperation to make sure the final products meet the ecological requirements. This leads the discussion back to the dependence of the local ecological system on the economic openness of a country. Even though the problem of ICT waste is faced at the global level, there is nevertheless a difference in the technological change triggered by the regulation between developed and developing economies.

Turning back to ET, it should be noted that the intensity of e-waste generation referred to the consumption of ICT is strongly dependent on the level of income and, therefore, is supposed to differ with the degree of economic development. As a consequence, the impact of ICT consumption on ET also in European countries can be different for Western economies and Eastern economies which could lead to different implications for environmental policies in these countries.

3. Methodology

3.1. Econometric Model

The aim of this study is to investigate, in addition to the most explored determinants of ET revenue in European countries, some non-trivial factors, such as the institutional context, the consumption of ICT goods and openness to international markets. In order to test the determinants of environmental taxation revenue we estimate the following model:

where ETRevit is environmental tax revenue of country i in year t; RoLit is the rule of law, ICTit and IMPit are, respectively, the importation of ICT goods and of other goods, while Zit represents a vector of other determinants of environmental taxation revenue such as: environmbental protection expenditure (Pub_exp); greenhouse gas emissions, expressed both in per capita (GGEpc) and per surface area (GGEsa) to take into account the criticism regarding the susceptibility of per capita pollution indicators (Luzzati and Orsini 2009); energy intensity of the economy (Intensity); and alternative and nuclear energy use (Altern_En).

ETRevit = α + β1RoLit + β2ICTit + β3IMPit + β4Zit + εit,

We measure the dependent variable in three ways: environmental taxation revenue as a percentage of GDP (ETRev_GDP), environmental taxation revenue as a percentage of total taxation revenue (ETRev_TAX) and total environmental taxation revenue (ETRev_TOT). All three variables are revenue-based indicators, although they measure the same phenomenon in different ways. The first one (ETRev_GDP) represents the weight of taxes in total income and can be considered as a proxy of a country environmental taxation burden, since it shows the amount of environmentally related tax revenues paid, considered as a proportion of gross domestic product. Secondly, since the environmental tax revenues can be affected by the overall tax burden, we believe it is appropriate also to use the environmentally related tax revenues as a percentage of total taxation revenues (ETRev_TAX) as a dependent variable. This indicator shows, ceteris paribus, the tax rates of the countries, since it reflects how green the overall taxation system is and represents the weight of environmental taxation on total taxation. The third way to introduce environmental taxation is to consider the total revenue from environmentally related taxes (ETRev_TOT) that is the product of a tax rate and a tax base, where the latter generally depends on the use of environmentally relevant goods (Bachus 2012) and, consequently, on the country’s size of gross domestic product.

Since the European countries come from different institutional and economic experiences, we expect that ET revenue determinants are not the same in countries with different backgrounds in economic welfare, institutional context, production technology and timing of joining the European Union. In fact, according to EEA (2005) environmental policies, including environmental taxation, are more effective in countries with high economic welfare and strong institutions, such as leaders (Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Finland, Norway, Germany, France and Italy) in application of Environmental Taxation Reform.

To better capture these differences in Europe, we divide the sample in two groups: Western European economies and Eastern European economies. The first group (G1) includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom, while the second group (G2) is composed of the following European developing countries: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. The countries of this second group are still characterised by a developing institutional context and lower living standards compared to the other European countries.

In the right-hand side of Equation (1) control variables are divided into the still unexplored determinants and the most well-known determinants of environmental taxation. Among the former category, firstly we take into account the institutional context, approximated by the rule of law indicator (RoL). The rule of law reflects the perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society that, according to our hypothesis, influences the enforcement and collection of ET revenue. Due to the diversities in institutional contexts among European countries, the impact of the rule of law on environmental taxation may be different for G1 and G2 groups. We expect that rule of law enforcement positively influences ET revenue in EU Western countries but this may not hold for EU Eastern countries.

Secondly, we account for the incidence of the ICT goods on environmental taxation by considering that those goods are a new source of technological waste since they are characterised by excessive rates of substitution. To capture the influence of ICT on ET revenue, considering that in European countries a high percentage of ICT goods are produced abroad and imported, we approximate ICT consumption by ICT imports. Also in this case the expected sign differs for the two groups of countries, given that their attitudes in ICT consumption are strongly related to income. For example, according to 2002/96/EC Directive and its updates on Waste Electric and Electronic Equipment (WEEE), manufacturers and distributors should pay an annual fee for the collection and recycling of associated waste electronics. As a consequence, the higher ICT imports in EU Western economies are expected to influence positively the ET revenues. However, this assertion may not be valid for EU Eastern economies for their lower levels of income and ICT consumption.

In addition, we consider whether importing other than ICT goods has an impact on ET revenue due to the transfer of industrial production processes (and consequently of the pollution deriving from these processes) abroad. We approximate this phenomenon with the imports of other than ICT goods. The expected sign also in this case differs depending on the group of the countries, in particular, on the degree of the development of their manufacturing sector. It cannot be excluded that offshoring of the production processes is a feature of the most developed economies and differences can be found between European countries.

Among the most explored determinants of environmental taxation, environmental protection expenditure is expected to decrease ETRev, given its positive impact on environment, while the other variables are expected to increase ET revenue since they reflect environmental degradation. Finally, the gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to influence positively the ET revenue because of its size (the higher the GDP, the higher the tax base) and composition, depending on the sectorial use of environmentally relevant goods.

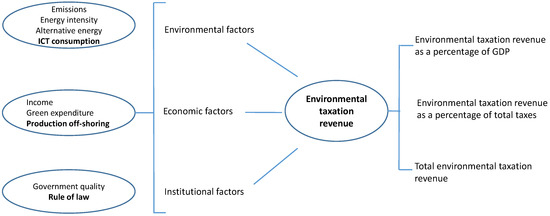

To sum up, we investigate the determinants of environmental taxation revenue, from different perspectives, putting emphasis on the importance of economic, environmental and institutional factors. The underlying structure of the model we estimate is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the model. ICT: information and communication technology.

3.2. Data and Descriptive Statistics

The data used in this analysis are derived from three sources: Eurostat (2014), Worldwide Governance Indicators (2014) and World Development Indicators (World Development Indicators 2014).

The data on environmental taxation revenue are taken from Eurostat Environmental Accounts. Eurostat (2001) defines as environmental any tax whose tax base is a physical unit (or a proxy of it) of something that has a proven, specific negative impact on the environment. Environmental related taxes include a vast range of environmental taxes on the tax bases such as energy products (energy products for transport purposes and energy products for stationary purposes), transport, pollution (measured or estimated emissions into the air, ozone depleting substances, measured or estimated effluents into water, non-point sources of water pollution, waste management, noise) and resources. Data on control variables, such as environmental protection expenditure, greenhouse gas emissions, energy intensity and the use of energy from alternative sources, are also taken from Eurostat (2014) database.

Data on the rule of law and government effectiveness indexes are taken from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (2014). The Worldwide Governance Indicators project reports governance indicators of more than 200 countries for six dimensions of governance. For the aim of the present work we have chosen two dimensions (Rule of law in the main model, and Government effectiveness in the robustness check model). These indicators are the most appropriate to examine the enforcement of environmental taxes in the EU. Both indicators are available every two years from 1996 to 2002, while data from 2003 to 2011 is given yearly. The missing data for the years 1997, 1999, 2001, is imputed as the average value between the two adjacent years. The indexes vary between −2.5 and +2.5, where the former represents a weak and the latter a strong rule of law and governance effectiveness. In order to use positive values, we sum +5 to this variable. These datasets are complemented by records on ICT imports and other goods imports provided by World Development Indicators (2014), and are expressed in constant prices.

The description of the data and sources are displayed in Table 1, while Table 2 presents a summary of the sample statistics. The upper part of the table displays the summary statistics of the G1-group (EU Western countries) while the lower part shows the same statistics for the G2-group (EU Eastern countries). It can be observed that all variables have a significant difference in mean between the two groups, with higher values for the developed countries, with the only exception of the total environmental tax revenues as percentage of total tax revenues that is 7.45 in G1 and in G2 is 0.764. A big difference can be observed, for example, for per capita gross domestic product that in G1 assumes the value of 36,600 and in the G2 of only 8841. However, what should be noted is a stronger institutional enforcement in the Western group (6.50 for the RoL and 6.59 for the Govern) compared to the Eastern group (5.5 for both the RoL and the Govern indicators). The summary statistics of the whole sample are shown in Table A1 in the Appendix A.

Table 1.

Variables description and sources.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3 displays mean and standard errors for each country of the sample (divided in two groups) for the three ET revenue indicators. In the upper part of the table it can be observed that, on average, especially the eco-leader countries, such as Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden together with Finland and Malta, have greater values compared with other countries. The tax revenue statistics suggest that the majority of G1 countries collects environmental tax revenue of about 3% of GDP, with the highest value for Denmark (4.62%) and the lowest for Spain (1.97%). In the G2 countries the highest percentage of environmental taxes in GDP is registered in Slovenia (3.55%) and the lowest in the Slovak Republic (2.11%). However, if we look at the weight of the environmental tax revenue in total tax revenue, which reflects how green the taxation system in European countries is, we find that in G1 countries the greenest taxation system is that of Malta (11.30%), followed by the Netherlands (9.6%) and Denmark (9.46), while the least green one is that of France, where only 4.87% of the overall tax revenues consist of environmental taxes. In G2 countries the greenest taxation system is in Slovenia (9.44%), while the least green one is in the Slovak Republic (6.60%). In the last two columns of Table 3, the mean and standard error statistics are referred to the total environmental tax revenue collected in each country. Clearly, the taxes collected depend on the size of GDP. Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy and France have the highest mean values among the G1 countries, while Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary present the highest mean values for the G2 countries.

Table 3.

Summary statistics of tax revenues in European countries.

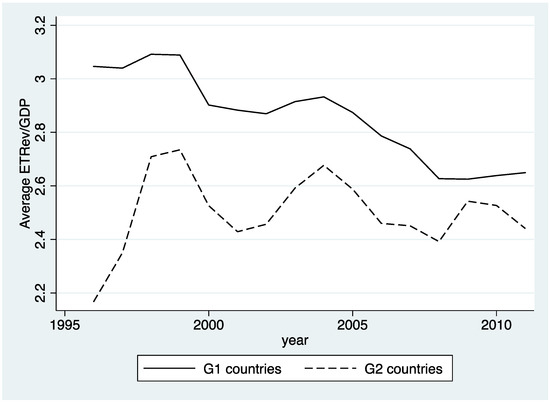

Figure 2 illustrates the tendencies of the last two decades in environmental taxation revenues in Western (G1) and Eastern (G2) EU countries. As the figure clearly shows, the level of environmental taxation revenue is higher for the former and much lower for the latter. However, due to the intervention of the European Union requiring the enforcement of environmental EU directives and the pollution abatement for all of its member states, some convergence in the levels of environmental taxation revenue is highlighted.

Figure 2.

Average environmental taxation revenue in G1 and G2 countries.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Main Results

Equation (1) is estimated using pooled cross-section and time-series data on 27 European countries for the period from 1996 to 2011. Given the length of the period, the first step of the analysis is to test the stationarity of the data. To this aim, the Im-Pesaran–Shin (IPS) (Im et al. 2003) test has been applied. The test allows for individual effects, time trends and common time effects, based on the mean of the individual Dickey–Fuller t-statistics of each unit in the panel. The null hypothesis is that all the panels contain a unit root (I(1) behaviour), and the alternative hypothesis is that all the panels are stationary (I(0) behaviour). Since the IPS test result shows that the null of unit root can be rejected at the one percent significance level, we conclude that the series are stationary. Therefore, Equation (1) is estimated using the natural logarithm form.

In estimating panel data, the effect of country-specific characteristics, potentially correlated with the dependent variable, can be explored by estimating both the fixed and random effects models (Cameron and Trivedi 2009). If country-specific characteristics are not correlated with the explanatory variables, the fixed effects should be preferred to random effects. Otherwise, the estimation of random effects is consistent and efficient. In order to choose between random and fixed effects we ran the Hausman test both for G1 and G2 group of European countries. For the G1 group of countries the statistic is equal to 69.75 (with a p-value of 0.000), for the latter the statistic is 0.20 (with a p-value of 0.999), whilst for the whole sample it is 59.90 (with a p-value of 0.000). Therefore, we proceeded in our analysis by applying the fixed effects model for the G1 group and for the whole sample, and the random effects model for the G2 group.

The results for the G1-group are presented in Panel A of Table 4, while the results for the G2-group are presented in Panel B of the same table. Columns 2–5 display the results when environmental tax revenue as a percentage of the GDP (ETRev_GDP) is taken as a dependent variable. Columns six and seven display the results when the total environmental tax revenue as a percentage of total tax revenue is used (ETRev_TAX), whilst the last two columns report the results when the total environmental tax revenue (ETRev_TOT) is considered.

Table 4.

Determinants of environmental taxation in in G1 and G2 EU countries.

In the upper part of Table 4 we observe the estimation results for our main explicative variables, i.e., the institutional context, ICT and other imports for G1 countries. The obtained results support our hypotheses. In particular, the coefficient of the rule of law that enforces the process of tax collection and monitoring, as expected, is positive and significant. This confirms the evidence on the importance of the institutional strength for environmental tax collection. The magnitude of this coefficient is around 1.0 for the first and the third model specification, while it is higher for the second specification (around 1.3). This means that as the rule of law increases by 1% the environmental revenues increase more than 1.1%.

A significant and positive relationship between ICT and environmental taxation revenue as percentage of GDP (first model specification) and total environmental revenue (third model specification) is also confirmed, although the elasticity parameters are rather low (around 0.06). As argued, high levels of income in G1 countries permit an intensive substitution of “obsolete” ICT goods with new upgraded ones. The excessive consumption, substitution and disposal of these goods in the home market imply the payment of taxes, which increases the volume of ET revenue. This result is not confirmed in the case when environmental taxation revenue is expressed as a percentage of total taxation (second model specification). This could be due to the fact that environmental revenues from e-waste are still a small part of total taxation revenue.

The incidence of total imports except ICT goods on ET revenue is negative and significant in all the estimations of the G1 group. For these economies, greater importation of manufacturing goods reflects a shrinking production sector at home, and, as a consequence, a lower environmental tax burden. In fact, according to our estimation, an increase of one percent of importation of goods decreases environmental taxation revenue by 0.16% in the estimation with ETRev_GDP as dependent variable and 0.25% and 0.13% in the estimation with ETRev_TAX and ETRev_TOT variables, respectively. These results confirm the evidence on the transferring abroad of the production process of EU Western countries and, as a consequence, a decrease in pollution.

As far as other control variables are concerned, we observe that the environmental policy expressed through government expenditure influences ET revenue negatively. This confirms that the expenditure to improve environmental quality contributes to the decrease of the environmental tax revenues. These results hold in all our estimations with a coefficient that is around 0.1. When environmental public expenditure increases by 10% the revenues decrease by one percent.

As highlighted in the econometric model paragraph, environmental degradation is considered by two different indicators (i.e., by per capita generation of greenhouse gases and by greenhouse gases per surface area). In both cases, as expected, the impact of environmental degradation on environmental taxation revenue is positive and is around 0.4 in all the three specifications. This means that when pollution increases by one percent the environmental taxation revenue increases by 0.4%, which is evidence of the functionality of the environmental tax reform that European countries have started during the last two decades.

To reflect the effects of production and consumption, energy intensity of the economy is also included in our model. Unexpectedly, for this variable we do not find any relationship with ET revenue. What we do observe is that the use of energy from alternative sources such as water, solar, wind, wave and nuclear energy has a positive and significant relationship with ET revenue in the first and the third model, although the impact is rather small (0.08).

Finally, in order to consider the role played by the size of the economy as the fiscal base for environmental taxation, in the second and third specifications of the model we take into account the impact of GDP. However, for the first model it was not possible to consider this variable given that the environmental taxation revenue is already expressed in terms of income. For this reason, in this model we have introduced GDP per capita as a control variable (columns four and five), which is significant at the 10% level only when also GGEsa is accounted for. However, in the second and third specifications of the model the total GDP is highly significant with a coefficient that is equal to 0.4 in the former and 0.9 in the latter case.

Panel B of Table 4 displays the estimated results for the EU Eastern countries. As expected, most of the above findings do not hold for this group of countries. In fact, none of our main determinants is found to have any impact on environmental taxation revenue. This result is due to many reasons. Firstly, this is probably because these countries are still characterised by a weak institutional context. As argued in the recent literature, the weakness of the institutions in these economies has a negative impact on the efficiency of environmental policies and on the quality of the environment. Secondly, the absence of the relationship between the imports and ET can be explained with the lower propensity of these economies to transfer the production processes abroad. As known, this can be the result of the FDI inflow (Gorbunova et al. 2012) and cheaper labour that these countries register with respect to the EU Western countries. In these countries, domestic production is still a significant factor, constituting a base for the environmental taxation entries. In fact, the size of the GDP positively influences the collection of environmental tax revenues when ETRev_TOT is considered as the dependent variable. Finally, lower levels of income of EU Eastern countries lead to lower importation and longer utilisation of existing technologies. For these reasons, they do not create as much specific technological waste and, therefore, green taxes, as do the EU Western countries.

However, the G2-group of countries presents a high level of significance with respect to two important variables related to environment policies. In fact, environmental policy expressed through government expenditure (Pub_exp) influences ET revenue negatively, which is expected given that the aim of this kind of expenditure is to improve environmental quality. This relation is homogeneous in the two groups of countries.

Interestingly, the use of energy from alternative sources (Altern_En) also influences ET revenue positively in both groups of countries. This can be explained by the subsidising of green technologies. In fact, the installation of green sources of energy is often subsidised by governments through the entries collected from environmental taxation (EEA 2005). It means that greater use of alternative energy sources is fuelled by increasing environmental taxes, which is confirmed by our findings that show very similar magnitude and significance of the parameters between the two groups. On the other hand, for the EU Eastern countries, a factor like GDP per capita has no influence on environmental taxation revenues, while the size of GDP significantly influences the collection of taxes only in the third model specification when the total amount of environmental taxation is taken as the dependent variable.

4.2. Robustness Tests

In order to check for the reliability of our results, we conducted a series of robustness tests. Firstly, we considered another variable reflecting the strength of institutional context such as the government effectiveness (Govern) indicator that is closely related to the rule of law (RoL). According to Kaufmann et al. (2010), this indicator reflects perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies, including environmental policies. Replacing the RoL variable with Govern we test whether the obtained results are influenced by the variable chosen. The findings are presented in Table A2 in the Appendix A. The estimated results do not seem to be sensitive to the use of a different explanatory institutional variable, in fact they are highly consistent with previous ones: (a) the Govern variable is found to hold a positive and significant relationship with environmental taxation revenue in the G1-group, but does not have a significant relationship with environmental taxation revenue in G2-group; (b) for the other control variables we observe that the signs and the level of significance are the same as in the previous estimations; (c) in the case of G2-group, the relationship with the environmental taxation revenue is found only for the Pub_exp and Altern_En variables, confirming that these countries have progressively and positively responded to the European Union laws and directives to combat pollution.

Secondly, since the number of European countries involved in each of the two groups is relatively small and some of the variables of interest do not have statistically significant impact on environmental tax revenues, in particular for G2 countries, we make an attempt to estimate the three model specifications on the whole sample. Table A2 in the Appendix A reports the estimated results. Our findings confirm the heterogeneity found in the two groups of countries. With respect to the results displayed in Table 4, despite the significance of most of the variables, we can observe that the magnitude of the determinants of environmental taxation revenue becomes less strong if compared with EU Western countries and stronger when compared with EU Eastern countries.

The estimations do not seem to be sensitive to the use of the whole sample of countries when they are compared with the G1 sample group estimations, although the magnitudes of the estimated parameters are smaller in the whole sample with respect to the G1-group. However, they seem to be very different when compared with the G2 sample estimations, confirming that the two groups of countries have different environmental tax revenues determinants.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we analyse the determinants of environmental taxation revenue in European countries. The importance of investigating ET determinants becomes crucial if we take into account the specific characteristics of this environmental policy instrument. On the one hand, excessive taxation of “bads”, as well as taxation of “goods”, undermines economic activity and household income. On the other hand, insufficient green taxation implies the acceleration of environmental degradation. In order to provide the policy-maker with the tools for establishing the right balance, it is necessary to have a clear vision of the factors affecting this policy instrument. To this end, together with most explored determinants of environmental taxation, we consider some hitherto neglected variables, such as the strength of institutions, the importation of ICT goods and the import of other goods than ICT goods. The analysis covers a panel of 27 European countries over the years 1996–2011.

Using three different indicators of environmental taxation, we find that the determinants of environmental taxation revenue vary across EU countries due to their different patterns of institutional and economic development. As we demonstrate, institutional enforcement in the form of the rule of law contributes positively to ET in EU Western countries, while EU Eastern economies with weaker institutions do not benefit from the rule of law enforcement. The importation of ICT goods that are characterised by rapid obsolescence turns out to be important. In EU Western countries the importation of these goods has a positive impact on ET revenues. Given the high per capita income of these countries, this effect may indicate rapid substitution of ICTs with technologically updated goods, thereby increasing waste production. Regarding policy implications, this is an important result. In fact, ICT goods, originally introduced to reduce the depletion of natural resources, can be now considered as a new source of technological waste that environmental taxation should take into consideration as “bads”. However, the relationship between environmental taxation and ICT importation is not significant for EU Eastern countries where, given lower levels of income, ICT goods are not so easily discarded and substituted by newer ones.

The importation of other than ICT goods is found to be negatively related to ET revenues in EU Western countries, while it has no influence in EU Eastern countries. This result indicates the transfer of industrial production to other countries and importation of goods produced abroad. As a result, this phenomenon leads to the decrease of environmental taxation in the home markets. We have found no confirmation of this hypothesis for EU Eastern countries that have not transferred their production processes abroad.

The traditional components that determine environmental taxation are those related to production and consumption processes and environmental degradation, i.e., energy intensity of the economy, the emission of greenhouse gases and environmental expenditure. As demonstrated, the aforementioned heterogeneity across European countries also persists in relation to these determinants. In fact, while environmental expenditure and the use of alternative sources of energy have, as expected, negative and positive signs in both groups of countries, the situation is different for the other two indicators. In fact, energy intensity contributes positively to environmental taxation in the EU Western countries, but not in EU Eastern countries. This may depend on the fact that in the latter countries the presence of lobbies and rent-seekers, supported by the weakness of the institutional context, hinders the introduction of environmental taxation. It is interesting to note that the variable that reflects environmental degradation, such as the release of greenhouse gases, is also not always significant in EU Eastern economies, confirming our hypothesis of the still tentative introduction of environmental policies and, consequently, on the lacunae in their application.

Finally, the results demonstrate that economic growth is also relevant in increasing environmental taxation revenues. As the GDP increases, the environmental taxation revenue increases for both Western and Eastern EU countries. We have found that ability to pay taxes, as expressed by the income per capita, is not relevant for environmental revenues, probably because the current environmental taxes are more related to macroeconomic issues than individual behaviour.

While our analysis confirms the importance of traditional determinants, its major contribution is the detection of less obvious factors, such as the rule of law, consumption of ICT goods and the import of goods produced abroad. We find evidence that these factors matter for ET in different ways in Western and Eastern European countries, and this should be taken into account by European countries when deciding environmental taxation policy and how to enforce it. Firstly, concerning the role played by the rule of law, the results highlight the importance of taking into account the institutional context for environmental policy decisions. The enforcement of rule of law, particularly in EU Western countries, can be seen as a fundamental tool to achieve functional applicability and collection of environmental taxes. Secondly, even if we have found a negative relationship between the total imports (except ICT) and environmental taxation revenues, mainly due to a shrinking production sector at home, this does not necessary imply a better environmental performance for EU Western countries. Due to the extensive phenomenon of pollution export, it seems necessary to enforce global environmental policies where developed economies are required to support less developed economies in achieving common objectives of environmental renaissance. Finally, new tendencies in consumption of ICT goods represent a serious threat for the local and global environment. More severe policies on fast product replacement, recycling and disposal of e-waste in production and consumption processes should be introduced primarily in developed European countries and enforced in developing European countries. According to a BIO Intelligence Service Report (BIO Intelligence Service 2013), it is expected that total WEEE will reach approximately 12.3 million tonnes by 2020 in the EU. The same report estimates that one third of the WEEE collected is treated domestically and 15% is exported to other countries, mostly for reuse. It is hard to estimate the quantities of WEEE exported illegally out of the EU. In this context, the explosion of ICT waste should become a matter of urgency for European and global environmental policies.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics, whole sample.

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics, whole sample.

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETRev_GDP | 448 | 2.730 | 0.676 | 1.180 | 5.170 |

| ETRev_TAX | 476 | 7.529 | 1.807 | 3.720 | 15.390 |

| ETRev_TOT | 444 | 1.25 × 1010 | 1.82 × 1010 | 1.11 × 108 | 7.26 × 1010 |

| RoL | 493 | 6.164 | 0.622 | 4.543 | 7.000 |

| Govern | 493 | 6.230 | 0.675 | 4.377 | 7.357 |

| ICT | 343 | 2.11 × 109 | 1.38 × 1010 | 3.45 × 108 | 1.14 × 1011 |

| IMP | 347 | 1.85 × 1010 | 2.59 × 1010 | 3.45 × 108 | 1.25 × 1011 |

| Pub_exp | 347 | 1.68 × 1011 | 2.21 × 1011 | 3.14 × 109 | 1.27 × 1012 |

| GGEpc | 328 | 14,351.970 | 14,183.610 | 6.236 | 82,806.460 |

| GGEsa | 454 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.028 |

| Intensity | 431 | 276.220 | 212.973 | 80.042 | 1411.170 |

| Altern_En | 485 | 14.529 | 14.681 | 0.000 | 50.734 |

| GDP | 489 | 4.86 × 1011 | 7.34 × 1010 | 4.62 × 109 | 3.07 × 1012 |

| GDPpc | 489 | 26,949.78 | 18,227.02 | 2353.987 | 87,716.73 |

Table A2.

Determinants of environmental taxation in G1 and G2 EU countries.

Table A2.

Determinants of environmental taxation in G1 and G2 EU countries.

| Variable | ETRev_GDP | ETRev_TAX | ETRev_TOT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A—G1 group | ||||||

| Govern | 0.500 *** | 0.621 *** | 0.691 *** | 0.764 *** | 0.553 *** | 0.643 *** |

| (0.147) | (0.143) | (0.164) | (0.159) | (0.153) | (0.149) | |

| ICT | 0.060 *** | 0.075 *** | 0.042 | 0.019 * | 0.070 *** | 0.079 *** |

| (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.025) | |

| IMP | −0.113 *** | −0.124 *** | −0.296 *** | −0.281 *** | −0.171 *** | −0.149 ** |

| (0.041) | (0.042) | (0.067) | (0.068) | (0.063) | (0.063) | |

| Pub_exp | −0.080 *** | −0.103 *** | −0.152 *** | −0.162 *** | −0.099 *** | −0.111 *** |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.028) | (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.025) | |

| GGEpc | 0.432 *** | .. | 0.289 *** | .. | 0.393 *** | .. |

| (0.089) | .. | (0.101) | .. | (0.094) | .. | |

| GGEsa | .. | 0.424 *** | .. | 0.271 *** | .. | 0.398 *** |

| .. | (0.089) | .. | (0.110) | .. | (0.103) | |

| Intensity | −0.056 | −0.036 | 0.016 | −0.032 | 0.012 | 0.003 |

| (0.122) | (0.121) | (0.144) | (0.152) | (0.134) | (0.143) | |

| Altern_En | 0.048 ** | 0.051 *** | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.058 *** | 0.055 *** |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.023) | (0.023) | |

| GDP | .. | .. | 0.760 *** | 0.692 *** | 1.225 *** | 1.104 *** |

| .. | .. | (0.199) | (0.216) | (0.187) | (0.203) | |

| Constant | 4.467 ** | 2.266 | −10.296 ** | −10.517 ** | −0.708 | −0.132 |

| (1.917) | (1.626) | (5.023) | (5.278) | (4.703) | (4.942) | |

| R−sq | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.56 |

| F−test | 36.38 | 36.02 | 24.74 | 24.11 | 20.01 | 19.44 |

| prob. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Obs | 148 | 148 | 148 | 148 | 148 | 148 |

| Panel B—G2 group | ||||||

| Govern | 0.339 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.674 | 0.332 | 0.389 |

| (0.524) | (0.482) | (0.497) | (0.471) | (0.526) | (0.504) | |

| ICT | −0.05 | −0.056 | 0.001 | 0.008 | −0.049 | −0.05 |

| (0.052) | (0.051) | (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.053) | (0.054) | |

| IMP | 0.063 | 0.074 | −0.033 | −0.031 | 0.070 | 0.101 |

| (0.090) | (0.095) | (0.119) | (0.109) | (0.127) | (0.115) | |

| Pub_exp | −0.054 *** | −0.052 *** | −0.039 *** | −0.043 *** | −0.054 *** | −0.052 *** |

| (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.017) | (0.017) | |

| GGEpc | 0.087 | .. | −0.088 | .. | 0.092 | .. |

| (0.148) | .. | (0.160) | .. | (0.183) | .. | |

| GGEsa | .. | 0.027 | .. | −0.128 | .. | 0.032 |

| .. | (0.126) | .. | (0.116) | .. | (0.144) | |

| Intensity | −0.075 | −0.057 | −0.023 | 0.005 | −0.08 | −0.058 |

| (0.148) | (0.149) | (0.131) | (0.135) | (0.147) | (0.158) | |

| Altern_En | 0.054 *** | 0.052 *** | 0.035 ** | 0.040 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.055 *** |

| (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.017) | (0.018) | |

| GDP | .. | .. | 0.029 | 0.076 | 0.988 *** | 0.954 *** |

| .. | .. | (0.106) | (0.114) | (0.120) | (0.134) | |

| Constant | 1.096 | 0.262 | 1.097 | −0.25 | 1.27 | 0.681 |

| (3.370) | (2.978) | (2.964) | (3.058) | (3.343) | (3.648) | |

| R−sq | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Wald(chi)2 | 27.33 | 27.13 | 18.22 | 19.89 | 457.05 | 389.2 |

| prob. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Obs | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Robust standard errors in parenthesis. * p < 0.001; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01. * G1 group includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom, while G2 group is composed of the following European developing countries: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

References

- Al-mulali, Usama, and Low Sheau-Ting. 2014. Econometric Analysis of Trade, Exports, Imports, Energy Consumption and CO2 Emission in Six Regions. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 33: 484–98. [Google Scholar]

- Anger, Niels, Christoph Bohringer, and Andreas Lange. 2006. Differentiation of Green Taxes: A Political-Economy Analysis for Germany. Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper No. 06-003. Mannheim: Centre for European Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bachus, Kris. 2012. Improving the methodology for measuring the greening of the tax system. In Green Taxation and Environmental Sustainability. Edited by Kreiser Lawrence, Ana Yábar Sterling, Pedro Herrera, Janet E. Milne and Hope Ashiabor. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, Jungho, S. Cho Young, and Won W. Koo. 2009. The Environmental Consequences of Globalization: A Country-Specific Time-Series Analysis. Ecological Economics 68: 2255–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, Leonardo, David A. Londono-Bedoya, and Luigi Paganetto. 2003. ICT Investment, Productivity and Efficiency: Evidence at Firm Level Using a Stochastic Frontier Approach. Journal of Productivity Analysis 20: 143–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, Antonio M., and Mark R. Jacobsen. 2007. Environmental policy and the “double-dividend” hypothesis. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 53: 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, Madhusudan, and Michael Hammig. 2001. Institutions and the Environmental Kuznets Curve for Deforestation: A Cross-Country Analysis for Latin America, Africa, and Asia. World Development 29: 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIO Intelligence Service. 2013. Equivalent Conditions for Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Recycling Operations Taking Place outside the European Union. Final Report Prepared for European Commission—DG Environment. Brussels: European Commission—DG Environment. [Google Scholar]

- Bluffstone, Randall A. 2003. Environmental Taxes in Developing and Transition Economies. Public Financial Management 3: 143–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenberg, A. Lans, and Ruud de Mooij. 1997. Environmental Tax Reform and Endogenous Growth. Journal of Public Economics 63: 207–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenberg, A. Lans, Lawrence H. Goulder, and Mark R. Jacobsen. 2008. Costs of alternative environmental policy instruments in the presence of industry compensation requirements. Journal of Public Economics 92: 1236–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Lorin Hitt. 1996. Paradox Lost? Firm Level Evidence on the Returns to Information Systems Spending. Management Science 42: 541–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A. Colin, and Pravin K. Trivedi. 2009. Microeconometrics Using Stata. Texas: College Station. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione, Concetta. 2012. Technical Efficiency and ICT Investment in Italian Manufacturing Firms. Applied Economics 44: 1749–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, Concetta, Davide Infante, and Janna Smirnova. 2012. Rule of law and the environmental Kuznets curve: evidence for carbon emissions. International Journal of Sustainable Economy 4: 254–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, Concetta, Davide Infante, and Janna Smirnova. 2014. Is There Any Evidence on the Existence of an Environmental Taxation Kuznets Curve? The Case of European Countries under their Rule of Law Enforcement. Sustainability 6: 7242–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, Matthew A. 2007. Corruption, Income and the Environment: an Empirical Analysis. Ecological Economics 62: 637–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, Valeria, and Chiara Martini. 2010. A Modified Environmental Kuznets Curve for Sustainable Development Assessment Using Panel Data. International Journal of Global Environmental Issues 10: 84–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damania, Richard, Per G. Fredriksson, and John A. List. 2003. Trade Liberalization, Corruption, and Environmental Policy Formation: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 46: 490–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, John. 2003. Regional Economic Integration, the Environment and Community: East Asia and APEC. International Review of Applied Economics 17: 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, Kuheli. 2009. Governance, Institutions and the Environmental-Income Relationship: A Cross-Country Study. Environment, Development and Sustainability 11: 705–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency—EEA. 2005. Market-Based Instruments for Environmental Policy in Europe. Technical Report No. 8. Copenhagen: European Environmental Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Ekins, Paul, and Terry Barker. 2001. Carbon Taxes and Carbon Emissions Trading. Journal of Economic Surveys 15: 325–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekins, Paul, Philip Summerton, Chris Thoung, and Daniel Lee. 2011. A Major Environmental Tax Reform for the UK: Results for the Economy, Employment and the Environment. Environmental and Resource Economics 50: 447–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 1997. Tax Provisions with a Potential Impact on Environmental Protection. Luxemburg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2007. A Lead Market Initiative for Europe Explanatory Paper on the European Lead Market Approach: Methodology and Rationale. Commission Staff Working Paper Document SEC (2007) 1730. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. 2001. Environmental Taxes. A Statistical Guide. Luxembourg: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. 2013. Taxation Trends in the European Union: Data for the EU Member States, Iceland, Norway and Luxembourg. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. 2014. Environmental Accounts. Available online: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/environmental_accounts/data/database (accessed on 1 September 2014).

- Fullerton, Don, and Gilbert E. Metcalf. 1997. Environmental Taxes and the Double-Dividend Hypothesis: Did You Really Expect Something for Nothing? NBER Working Paper No. 6199. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunova, Yulia, Davide Infante, and Janna Smirnova. 2012. New Evidences on FDI Determinants. An Appraisal over the Transition Period. Prague Economic Papers 2: 129–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Robert J. 2002. Technology and Economic Performance in the American Economy. NBER Working Paper Series No. 8771. Evanston: Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- Goulder, Lawrence H. 2013. Climate change policy’s interactions with the tax system. Energy Economics 40: S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Bronwyn H., Francesca Lotti, and Jacques Mairesse. 2013. Evidence on the Impact of R&D and ICT Investments on Innovation and Productivity in Italian Firms. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 22: 300–28. [Google Scholar]

- Im, Kyung So, M. Hashem Pesaran, and Yongcheol Shin. 2003. Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panel. Journal of Econometrics 115: 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, Davide, and Janna Smirnova. 2016. Environmental Technology Choice in the Presence of Corruption and the Rule of Law Enforcement. Transformation in Business & Economics 15: 214–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, Kate. 2010. Corruption and Air Pollution in Europe. Oxford Economic Papers 63: 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampas, Athanasios, and Richard Horan. 2016. Second-Best Pollution Taxes: Revisited and Revised. Environmental Economics and Policy Studies 18: 577–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karydas, Christos, and Lin Zhang. 2017. Green tax reform, endogenous innovation and the growth dividend. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2010. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: A Summary of Methodology, Data and Analytical Issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5430. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Worldwide Governance Indicators. 2014. The Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) Project. Available online: http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home (accessed on 1 September 2014).

- Kosonen, Katri. 2010. Why Are Environmental Tax Revenues Falling in the European Union? In Critical Issues in Environmental Taxation. Edited by Soares Claudia Dias, Janet Milne, Hope Ashiabor and Kurt Deketelaere. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lipford, Jody W., and Bruce Yandle. 2010. Environmental Kuznets Curves, Carbon Emissions, and Public Choice. Environment and Development Economics 15: 417–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzati, Tommaso, and Marco Orsini. 2009. Natural Environment and Economic Growth: Looking for the Energy-EKC. Energy 34: 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markandya, Anil, Alexander Golub, and Suzette Pedroso-Galinato. 2006. Empirical Analysis of National Income and SO2 Emissions in Selected European Countries. Environmental and Resource Economics 35: 221–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, Adrian, and Thomas Sterner. 2006. Environmental Taxation in Practice. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis Ltd., Ashgate Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2008. Environmental Outlook to 2030. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotou, Theodore. 1997. Demystifying the Environmental Kuznets Curve: Turning a Black Box into a Policy Tool. Environment and Development Economics 2: 465–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, Maria Laura, Fabio Schiantarelli, and Alessandro Sembenelli. 2002. Productivity, Innovation Creation and Absorption, and R&S: Micro Evidence for Italy. Working Paper in Economics, n.526. Chestnut Hill: Boston College. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, Lorenzo, and Reyer Gerlagh. 2006. Corruption, democracy, and environmental policy. An empirical contribution to the debate. The Journal of Environment and Development 15: 332–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Alfredo Marvao, and Rui Marvao Pereira. 2017. Achieving the triple dividend in Portugal: A dynamic general-equilibrium evaluation of a carbon tax indexed to emissions trading. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 20: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, E. Michael, and Claas van der Linde. 1995. Toward a new conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 9: 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrimgeour, Frank, Les Oxley, and Koli Fatai. 2005. Reducing Carbon Emissions? The Relative Effectiveness of Different Types of Environmental Tax: the Case of New Zealand. Environmental Modelling & Software 20: 1439–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sterner, Thomas, and Gunnar Köhlin. 2003. Environmental Taxes in Europe. Public Finance and Management 3: 117–42. [Google Scholar]

- Taheripour, Farzad, Madhu Khanna, and Carl H. Nelson. 2008. Welfare Impacts of Alternative Public Policies for Agricultural Pollution Control in an Open Economy: A General Equilibrium Framework. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 90: 701–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Shiro. 2007. The double dividend from carbon regulations in Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 21: 336–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Xin, Jin Shi, and Yu Zhou. 2012. Greening of Supply Chain in Developing Countries: Diffusion of Lead (Pb)-Free Soldering in ICT Manufacturers in China. Ecological Economics 83: 174–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2012. E-Waste. Volume III. WEEE/e-Waste Take Back System. Osaka: United Nations Environmental Programme, Division of Technology, Industry and Economics, International Environmental Technology Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Hugh, and Xun Cao. 2012. Domestic and International Influences on Green Taxation. Comparative Political Studies 45: 1075–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, Benjamin, and Robert U. Ayres. 2012. Useful work and information as drivers of economic growth. Ecological Economics 73: 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Roberton C. 2002. Environmental Tax Interactions when Pollution Affects Health or Productivity. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 44: 261–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Development Indicators. 2014. The World Bank World Development Indicators. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/products/wdi (accessed on 1 September 2014).

- Yamazaki, Akion. 2017. Jobs and climate policy: Evidence from British Columbia’s revenue-neutral carbon tax. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 83: 197–216. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).