Does Trust Matter for Entrepreneurship: Evidence from a Cross-Section of Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

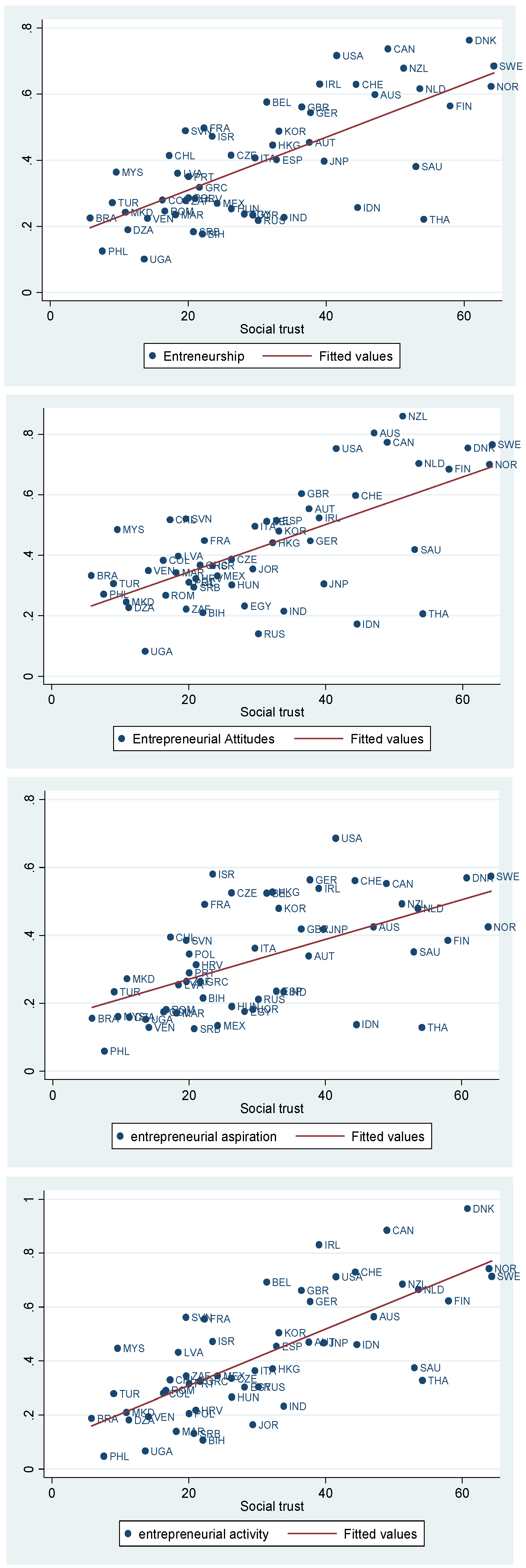

3. Data and Descriptive Findings

“there should be detailed information about the applied data set and the sources of the variables. The 14 individual pillars of entrepreneurship used in the construction of our index are calculated by involving more than 963,000 individuals from the 71 countries. The pillars themselves are constructed through an interaction of individual level and institutional variables. All of the institutional variables are from the Global Competitiveness Index; others are from the Doing business, Index of economic Freedom or from multinational organizations such as the UNIDO or OECD. While we tried to find a single institutional variable for each of the individual variables, sometimes it proved to be not executable. Therefore some of these institutional variables are themselves complex ‘indexes’. Comparing to the previous versions of our index, we avoided the duplication or the multiplication of the same institutional factors in different part of the index.”

4. Empirical Model

“I firstly include a dummy for whether countries are monarchies, which Bjørnskov (2007) finds to be approximately eight percentage points more trusting than countries without hereditary institutions. Secondly, I follow Tabellini’s (2008) approach of study in including a dummy variable for whether a country’s predominant language allows dropping the subjective pronoun, that is, Chomsky’s (1981) ‘pro-drop’ characteristic. Tabellini’s argument rests on Kashima and Kashima (1998) in arguing that cultures in which the language forbids dropping the personal pronoun traditionally have been more respectful of individual rights and have therefore developed stronger trust norms” (Bjørnskov, 2012:6) […]These are supplemented by the average temperature in the coldest month of the year, based on the premise, dating back to Aristotle, that trust and social cohesion historically has been relatively more important for survival in regions with cold winters, and that cultures of such regions may have selected high-trust institutions through an evolutionary process”.(Bjørnskov, 2010 [16]: p. 336)

5. Econometric Findings

5.1. Regression Results with the Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index (GEDI)

5.1.1. Main Regression Results

5.1.2. Robustness Checks

5.2. Regression Results with Sub-Indexes

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A. Alesina, and E. La Ferrara. “Who Trusts Others? ” J. Public Econ. 85 (2002): 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- C. Bjørnskov. “Determinants of Generalized Trust: A Cross-Country Comparison.” Public Choice 130 (2006): 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- A. Smith. “The Determinants of Trust: An Experimental Approach.” In Proceedings of the CEA 42nd Annual Meetings, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–8 June 2008.

- S. Knack, and P. Keefer. “Does social capital have an economic pay-off? A cross-country investigation.” Q. J. Econ. 112 (1997): 1251–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Whiteley. “Economic growth and social capital.” Political Stud. 48 (2000): 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Zak, and S. Knack. “Trust and Growth.” Econ. J. 111 (2001): 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Beugelsdijk, H.L.F. de Groot, and A. van Schaik. “Trust and economic growth: A robustness analysis.” Oxford Econ. Papers 56 (2004): 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- N. Berggren, M. Elinder, and H. Jordahl. “Trust and Growth: A Shaky Relationship.” Empir. Econ. 35 (2008): 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. Kodila-Tedika, and S Asongu. Trust and Prosperity: A Conditional Relationship. Working Papers 13/024; Yaoundé, Cameroon: African Governance and Development Institute, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- C. Bjørnskov, and P.-G. Méon. The Productivity of Trust. CEB Working Paper No 10/042; Brussels, Belgium: Université Libre de Bruxelles-Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management, Centre Emile Bernheim, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- J.F. Helliwell, and R. Putnam. “Economic growth and social capital in Italy.” East. Econ. J. 221 (1995): 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- R. La Porta, F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R.W. Vishny. “Trust in large organizations.” Am. Econ. Rev. 87 (1997): 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- T.W. Rice, and A. Sumberg. “Civic culture and democracy in the American states.” Publius 23 (1997): 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Knack. “Social capital and the quality of government: Evidence from the US states.” Am. J. Political Sci. 46 (2002): 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Bjørnskov, A. Dreher, and J. Fischer. “Formal Institutions and Subjective Well-Being: Revisiting the Cross-Country Evidence.” Eur. J. Political Econ. 26 (2010): 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Bjørnskov. “How does Social Trust lead to Better Governance? An Attempt to Separate Electoral and Bureaucratic Mechanisms.” Public Choice 144 (2010): 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Bjørnskov. “How Does Social Trust Lead to Economic Growth? ” South. Econ. J. 78 (2012): 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Bergh, and C. Bjørnskov. “Historical Trust Levels Predict Current Welfare State Design.” In Proceedings of the IAREP/SABE 2009 Conference, Halifax, Canada, July 2009.

- C. Bjørnskov. “Social Trust and the Growth of Schooling.” Econ. Educ. Rev. 28 (2009): 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I.S. Akçomak, and B. ter Weel. “Social capital, innovation and growth: Evidence from Europe.” Eur. Econ. Rev. 53 (2009): 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Greif. “Reputation and coalitions in medieval trade: Evidence on the Maghribi traders.” J. Econ. History 49 (1989): 857–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Woolcock. “Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework.” Theory Soc. 27 (1998): 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F.A.G. Den Butter, and R.H.J. Mosch. Trade, Trust and Transaction Cost. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper No 03–082/3; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Tinbergen Institute, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- W.J. Wilson. The Truly Disadvantaged. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- R. Rose. “How much does social capital add to individual health? A survey study of Russians.” Soc. Sci. Med. 51 (2000): 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Bjørnskov. “The happy few: Cross-country evidence on social capital and life satisfaction.” Kyklos 56 (2003): 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.F. Helliwell. “How’s life? Combining individual and national variables to explain subjective well–being.” Econ. Model. 20 (2003): 331–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Harper. Foundations of Entrepreneurship and Economic Development. London, UK: Routledge, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- M. Fafchamps. “Networks, communities and markets in SSA; implications for firm growth and investment.” J. Afr. Econ. 10 (2002): 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Berggren, and H. Jordahl. “Free to trust? Economic freedom and social capital.” Kyklos 59 (2006): 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.W. Hafer, and G. Jones. “Are entrepreneurship and cognitive skills related? Some international evidence.” Small Bus. Econ. 44 (2015): 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.G. Holcombe. “Entrepreneurship and economic growth.” Q. J. Austrian Econ. 1 (1998): 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.A. Caree, and A.R. Thurik. “The Impact of Entrepreneurship on Economic Growth.” Available online: http://www.hadjarian.com/esterategic/tarjomeh/2-89-karafariny/1.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2016).

- D.B. Audretsch, D.B. Keilbach, and E.E. Lehmann. Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- I. Kirzner. “Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market process: An Austrian approach.” J. Econ. Lit. 35 (1997): 60–85. [Google Scholar]

- E.P. Lazear. “Balanced skills and entrepreneurship.” Am. Econ. Rev. 94 (2004): 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.P. Lazear. “Entrepreneurship.” J. Labor Econ. 23 (2005): 649–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.J. Acs, and L. Szerb. The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index (GEDI), Paper presented at “Opening up Innovation: Strategy, Organization and Technology”. London, UK: Imperial College, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- S. Geindre, and B. Dussuc. “Capital Social, Théorie des Réseaux Sociaux et Recherche en PME: Une Revue de la Littérature.” In Proceedings of the 11ème Congrès CIFEPME (Congrès International Francophone en Entrepreneuriat et PME), Brest, France, October 2012.

- D. Chabaud, and J. Ngijol. “La contribution de la théorie des réseaux sociaux à la reconnaissance des opportunités de marché.” Revue Int. P.M.E. 18 (2005): 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Bhagavatula, T. Elfring, A. van Tilburg, and G.G. van de Bunt. “How social and human capital influence opportunity recognition and resource mobilization in India’s handloom industry.” J. Bus. Ventur. 25 (2010): 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.B. Audretsch, T.T. Aldridge, and M. Sanders. “Social capital building and new business formation: A case study in Silicon Valley.” Int. Small Bus. J. 29 (2011): 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Mueller. “Entrepreneurship in the Region: Breeding Ground for Nascent Entrepreneurs? ” Small Bus. Econ. 27 (2006): 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Davidsson, and B. Honig. “The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs.” J. Bus. Ventur. 18 (2003): 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- M.J. Rodríguez, and F.J. Santos. “Women nascent entrepreneurs and social capital in the process of firm creation.” Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 5 (2007): 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Clarke, and R. Chandra. “Bridging voids: Constraints on Hispanic entrepreneurs building social capital.” Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 14 (2011): 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Deakins, M. Ishaq, D. Smallbone, G. Whittam, and J. Wyper. “Ethnic Minority Businesses in Scotland and the Role of Social Capital.” Int. Small Bus. J. 25 (2007): 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.A. Baron, and G.D. Markman. “Beyond social capital: The role of entrepreneurs’ social competence in their financial success.” J. Bus. Ventur. 18 (2003): 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.C. Runyan, P. Huddleston, and J. Swinney. “Entrepreneurial orientation and social capital as small firm strategies: A study of gender differences from a resource-based view.” Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2 (2006): 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Honig, M. Lerner, and Y. Raban. “Social Capital and the Linkages of High-Tech Companies to the Military Defense System: Is there a Signaling Mechanism? ” Small Bus. Econ. 27 (2006): 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K.A. Packalen. “Complementing capital: The role of status, demographic features, and social capital infounding teams’ abilities to obtain resources.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 31 (2007): 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Geindre. “Le transfert de la ressource réseau lors d’un processus de reprise.” Revue Int. P.M.E. 22 (2009): 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Aarstad, S.A. Haugland, and A. Greve. “Performance Spillover Effects in Entrepreneurial Networks: Assessing a Dyadic Theory of Social Capital.” Entrep. Theory Pract. 34 (2010): 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Bosma, M. van Praag, R. Thurik, and G. de Wit. “The value of human and social capital investments for the business performance of startups.” Small Bus. Econ. 23 (2004): 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Mosek, M. Gillin, and L. Katzenstein. “Evaluating the donor: Enterprise relationship in a not-for-profit social entrepreneurship venture.” Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 4 (2007): 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Han. “Developing social capital to achieve superior internationalization: A conceptual model.” J. Int. Entrep. 4 (2007): 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N.E. Coviello, and M.P. Cox. “The resource dynamics of international new venture networks.” J. Int. Entrep. 4 (2007): 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Doh, and Z. Acs. “Innovation and Social Capital: A Cross-Country Investigation.” Ind. Innov. 17 (2010): 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Doepke, and F. Zilibotti. “Culture, Entrepreneurship, and Growth.” Handb. Econ. Growth 2 (2014): 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. “Human Development Report 2004.” Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2004 (accessed on 2 March 2016).

- Heritage Foundation. “2010 Index of Economic Freedom.” Available online: http://www.heritage.org/index/pdf/2010/index2010_full.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2016).

- “World Values Survey Wave 6 (2010–2014).” Available online: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp (accessed on 2 March 2016).

- R. Lynn, and G. Meisenberg. “National IQs calculated and validated for 108 nations.” Intelligence 38 (2010): 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Kaufmann, A. Kraay, and M. Mastruzzi. “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues.” Available online: http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/pdf/WGI.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2016).

- R.J. Barro, and J.W. Lee. “A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950–2010.” J. Dev. Econ. 104 (2013): 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Penn World Table 7.1.” Available online: http://knoema.fr/PWT2012/penn-world-table-7-1 (accessed on 2 March 2016).

- C. Bjørnskov, and N.J. Foss. “Economic freedom and entrepreneurial activity: Some cross-country evidence.” Public Choice 134 (2008): 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.L. Glaeser, W.R. Kerr, and G.A.M. Ponzetto. “Clusters of entrepreneurship.” J. Urban Econ. 67 (2010): 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.L. Glaeser, S.S. Rosenthal, and W.C. Strange. “Urban economics and entrepreneurship.” J. Urban Econ. 67 (2010): 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. Kalonda-Kanyama, and O. Kodila-Tedika. Quality of Institutions: Does Intelligence Matter? Working Papers 308; Cape Town, South Africa: Economic Research Southern Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Z.J. Acs. “How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? ” Innovations 1 (2010): 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Lynn, and T. Vanhanen. “National IQs: A review of their educational, cognitive, economic, political, demographic, sociological, epidemiological, geographic and climatic correlates.” Intelligence, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Jones, and W.J. Schneider. “IQ in the production function: Evidence from immigrant earnings.” Econ. Inq. 48 (2010): 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. White. “A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity.” Econometrica 48 (1980): 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Potrafke. “Intelligence and Corruption.” Econ. Lett. 141 (2012): 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1This study focuses on the period from 2002 to 2011.

- 2See Doepke and Zilibotti (2014) [59] for a model.

- 3As suggested in the literature (see, Hafer and Jones, 2015 [31]), both variables—IQ and schooling years—can be maintained in the same regression so as to capture competing aspects of human capital.

- 4See Lynn and Vanhanen (2012) [72] for literature on this subject.

- 5Some regions were dropped due to multicollinearity.

| Variables | Sources |

|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | Acs and Szerb, (2010) [38]. |

| Gini | GINI coefficient (UNDP, Human Development Report, 2004 [60]) |

| Post-communist | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| Economic freedom | 2010 Index of Economic Freedom (Heritage Foundation [61]) |

| Social trust | World Values Survey (2010) [62] |

| IQ | Lynn and Meisenberg, (2010) [63] |

| Regulatory quality | World Bank Governance indicator. The measures come from the dataset compiled by Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi at the World Bank, (2010) [64] |

| MENA | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| High income | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| East Asia and Pacific | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| Education 1 (average years of schooling in population aged 25 and above) | Barro and Lee (2011) [65] |

| Education 2 (average years of schooling in population aged 15 and above) | Barro and Lee (2011) [65] |

| Log GDP per capita | Pen World Tables 7v (2010) [66] |

| Africa | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| Americas | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| Asia | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| Europa | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| Oceania | Dummy variable. Author’s own |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | 60 | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.1 | 0.76 |

| Gini | 54 | 36.65 | 9.39 | 24.00 | 59.00 |

| Post-communist | 60 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Economic freedom | 60 | 66.20 | 10.25 | 37.10 | 89.70 |

| Trust | 53 | 30.42 | 15.57 | 5.77 | 64.27 |

| IQ | 59 | 93.19 | 8.28 | 72.00 | 108.00 |

| Regulatory quality | 52 | 0.58 | 0.90 | −1.35 | 1.94 |

| MENA | 60 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| High income | 60 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| East Asia and Pacific (EAP) | 60 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) | 60 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Education 1 | 51 | 8.97 | 2.43 | 3.86 | 13.09 |

| Education 2 | 51 | 9.14 | 2.15 | 4.32 | 12.75 |

| Log GDP per capita | 52 | 9.51 | 1.44 | 4.86 | 12.44 |

| Africa | 60 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Americas | 60 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Asia | 60 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Europa | 60 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Oceania | 60 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Entrepreneurship | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 2 Gini | −0.41 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 3 Post communist | −0.23 | −0.27 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 4 Economic freedom | 0.79 | −0.27 | −0.21 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 5 IQ | 0.68 | −0.62 | 0.18 | 0.54 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 6 Trust | 0.71 | −0.47 | −0.27 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 7 Regulatory quality | 0.79 | −0.48 | −0.02 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 8 Log GDP per capita | 0.76 | −0.41 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 9 Education 1 | 0.72 | −0.45 | 0.20 | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 1.00 | |||||

| 10 Education 2 | 0.70 | −0.42 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 1.00 | ||||

| 11 High income | 0.19 | −0.20 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 1.00 | |||

| 13 Entrepreneurial activity | 0.95 | −0.40 | −0.24 | 0.73 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 1.00 | ||

| 14 Entrepreneurial aspiration | 0.90 | −0.45 | −0.11 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.55 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 1.00 | |

| 12 Entrepreneurial attitudes | 0.92 | −0.30 | −0.26 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.72 | 1.00 |

| Social Trust | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | Entrepreneurial Attitudes | Entrepreneurial Activity | Entrepreneurial Aspiration | |

| Monarchy | 5.214 (3.946) | 7.197 ** (3.672) | 7.197 ** (3.672) | 7.197 ** (3.672) |

| Pronoun drop | 10.819 *** (3.813) | 8.709 ** (3.820) | 8.709 ** (3.820) | 8.709 ** (3.820) |

| Temperature | 0.124 (0.262) | −0.360 (0.281) | −0.360 (0.281) | −0.360 (0.281) |

| R² | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Obs | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | 0.008 *** (0.001) | 0.003 * (0.001) | 0.003 * (0.001) | 0.006 ** (0.003) |

| Gini | −0.000 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.002) | 0.002 (0.004) | |

| Post-communist | −0.091 * (0.048) | −0.106 * (0.045) | −0.037 (0.093) | |

| IQ | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.004) | |

| Economic freedom | 0.006 * (0.003) | 0.006 * (0.002) | 0.004 (0.003) | |

| High income | −0.010 (0.028) | −0.019 (0.027) | −0.007 (0.041) | |

| Education 1 | 0.022 * (0.010) | 0.019 * (0.008) | 0.012 (0.015) | |

| SSA | 0.010 (0.032) | 0.051 (0.068) | ||

| MENA | −0.076 ** (0.045) | −0.083 (0.072) | ||

| EAP | −0.074 ** (0.041) | −0.138 (0.103) | ||

| R² | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.86 |

| Obs | 53 | 47 | 47 | 39 |

| Sargan | 0.30 | |||

| Basmann | 0.42 | |||

| OLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2SLS | No | No | No | Yes |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | 0.008 *** (0.002) | 0.003 * (0.000) | 0.029 * (0.001) | 0.003 * (0.001) | 0.003 * (0.001) | 0.003 * (0.001) | 0.008 * (0.004) |

| Gini | −0.000 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.000 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.002) | −0.001 (0.002) | 0.004 (0.006) | |

| Post-communist | −0.091 * (0.026) | −0.106 * (0.026) | −0.129 ** (0.043) | −0.115 ** (0.041) | −0.120 * (0.049) | −0.022 (0.110) | |

| IQ | 0.004 (0.002) | 0.004 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.004 ** (0.004) | |

| Economic freedom | 0.006 (0.003) | 0.006 (0.003) | 0.005 (0.002) | 0.008 *** (0.002) | 0.005 * (0.002) | 0.004 (0.005) | |

| High income | −0.010 (0.020) | −0.018 (0.019) | −0.005 (0.024) | −0.014 (0.023) | −0.012 (0.030) | 0.020 (0.049) | |

| Education 1 | 0.022 (0.011) | 0.019 (0.011) | 0.022 (0.008) | 0.019 * (0.007) | 0.020 * (0.010) | 0.011 (0.014) | |

| SSA | 0.010 (0.030) | −0.015 (0.034) | 0.023 (0.037) | −0.021 (0.064) | -0.019 * (0.043) | ||

| MENA | −0.076 * (0.035) | −0.071 (0.045) | −0.047 (0.043) | −0.076 * (0.044) | −0.033 ** (0.068) | ||

| EAP | −0.074 (0.044) | −0.069 (0.044) | −0.023 (0.041) | −0.134 *** (0.093) | |||

| R² | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.88 | |

| Obs | 53 | 47 | 47 | 46 | 45 | 47 | 37 |

| Outliers | Slovenia | Slovenia Venezuela | Slovenia Venezuela | ||||

| IWLS | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| OLS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 2SLS | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | 0.004 *** (0.001) | 0.003 * (0.001) | 0.003 * (0.002) | 0.007 * (0.003) |

| Gini | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.003) | −0.001 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.005) |

| Post-communist | −0.084 ** (0.042) | −0.099 * (0.043) | −0.113 * (0.051) | −0.076 (0.074) |

| IQ | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.004 (0.004) | 0.003 (0.004) | 0.006 (0.004) |

| Regulatory quality | 0.075 *** (0.024) | 0.075 *** (0.028) | 0.086 ** (0.030) | 0.023 (0.039) |

| Log GDP per capita | 0.012 (0.016) | 0.007 (0.021) | −0.010 (0.022) | −0.002 (0.026) |

| Education 2 | 0.015 (0.010) | 0.017 ** (0.010) | 0.019 (0.013) | 0.024 * (0.013) |

| Africa | 0.014 (0.075) | −0.032 (0.086) | 0.0061 (0.076) | |

| Asia | −0.027 (0.084) | −0.104 (0.087) | −0.071 (0.078) | |

| Europe | −0.022 (0.063) | −0.069 (0.081) | −0.000 (0.057) | |

| Oceania | 0.008 (0.057) | −0.035 (0.083) | −0.024 (0.051) | |

| Americas | −0.004 (0.075) | −0.035 (0.090) | 0.017 (0.073) | |

| R² | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.88 | |

| Obs | 47 | 47 | 47 | 37 |

| IWLS | No | No | Yes | No |

| OLS | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 2SLS | No | No | No | No |

| Outliers | Slovenia Venezuela |

| Entrepreneurial Attitudes | Entrepreneurial Activity | Entrepreneurial Aspiration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | 0.004 * (0.002) | 0.003 ** (0.001) | 0.013 *** (0.004) | 0.005 *** (0.002) | 0.006 *** (0.002) | 0.008 (0.006) | 0.000 (0.001) | 0.000 (0.001) | −0.001 (0.004) |

| Method | OLS | IWLS | 2SLS | OLS | IWLS | 2SLS | OLS | IWLS | 2SLS |

| R² | 0.7538 | 0.83 | 0.7693 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.77 | |||

| Obs | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 39 |

| Sargan | 0.198 | 0.303 | 00.082 | ||||||

| Basmann | 0.308 | 0.428 | 0.148 | ||||||

| Robustness Checks Using Alternative Conditioning Variables | |||||||||

| Trust | 0.003 * (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.010 * (0.004) | 0.006 *** (0.002) | 0.006 *** (0.002) | 0.006 (0.005) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.004) |

| Method | OLS | IWLS | 2SLS | OLS | IWLS | 2SLS | OLS | IWLS | 2SLS |

| R² | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.70 | |||

| Obs | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kodila-Tedika, O.; Agbor, J. Does Trust Matter for Entrepreneurship: Evidence from a Cross-Section of Countries. Economies 2016, 4, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies4010004

Kodila-Tedika O, Agbor J. Does Trust Matter for Entrepreneurship: Evidence from a Cross-Section of Countries. Economies. 2016; 4(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies4010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleKodila-Tedika, Oasis, and Julius Agbor. 2016. "Does Trust Matter for Entrepreneurship: Evidence from a Cross-Section of Countries" Economies 4, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies4010004

APA StyleKodila-Tedika, O., & Agbor, J. (2016). Does Trust Matter for Entrepreneurship: Evidence from a Cross-Section of Countries. Economies, 4(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies4010004