1. Introduction

Dispersed urban expansion, a phenomenon known worldwide with the term “urban sprawl”, determines changes in both urban patterns (e.g., settlement morphology and urban form) and processes (spatial distribution of economic functions, socio-spatial disparities, political and cultural factors consolidating the role of peri-urban areas). Physical elements related to space, have been extensively evaluated in order to analyse how sprawl has manifested and taken place in metropolitan regions (Southworth and Owens, 1993 [

1]; Tsai, 2005 [

2]; Kazepov, 2005 [

3]; Couch

et al., 2007 [

4]). Urban sprawl would be possible under a variety of political, economic and cultural conditions which manifested itself worldwide (Burchell

et al., 1998 [

5]). Sprawl is identifiable in suburban areas where low-density residential settlements have progressively replaced the traditional agricultural and forest mosaic leading to a mixed and undefined landscape, disseminated of detached family houses, where population is highly dependent on private transport (Ewing

et al., 2002 [

6]; Tsai, 2005 [

2]; Torrens, 2008 [

7]). The main causes of sprawl can be envisaged in (i) a complex system of interacting agents at the base of the dispersed expansion of cities and metropolitan regions (Gargiulo Morelli and Salvati, 2010 [

8]); (ii) lack of efficient planning systems at the regional scale and, more frequently, at the urban scale (Gibelli and Salzano, 2006 [

9]); (iii) a generalized misuse of non-urban land determined by policies regulating cities’ growth and the development of peri-urban regions (Giannakourou, 2005 [

10]).

Sprawl can be thus considered an intriguing spatial model involving social, economic and environmental issues and reflecting the interplay between urban patterns and development processes (Burchell

et al., 1998 [

5]; Galster

et al., 2001 [

11]; Frenkel and Ashkenazi, 2008 [

12]; Orenstein

et al., 2013 [

13]). Since sprawl is based on a number of interacting factors, it is difficult to understand how urban dispersion is structured over time and scale (Kazepov, 2005 [

3]; Couch

et al., 2007 [

4]; Cassier and Kesteloot, 2012 [

14]), making it difficult to implement appropriate strategies of urban containment and sustainable land-use management policies (Bruegmann, 2005 [

15]; Hall and Pain, 2006 [

16]; Angel

et al., 2011 [

17]). From these premises, sprawl appears to be a key issue for contemporary cities, due to the overpowering degree of

laissez-faire policies (Costa

et al., 1991 [

18]).

Southern Europe is an interesting case for studying the impact of dispersed urban expansion on different models of local development. The spread of low-density settlements from inner cities to suburban areas is a traditional phenomenon for North American cities observed since the beginning of the twentieth century (e.g., Duany

et al., 2000 [

19]; Bruegmann, 2005 [

15]). By contrast, sprawl can be identified as an untraditional—and possibly more recent—development model for some European cities, especially those situated in the Mediterranean Europe (European Environment Agency, 2006 [

20]; Kasanko

et al., 2006 [

21]; Couch

et al., 2007 [

4]). From the 1970s, urban dispersion advanced rapidly in European Mediterranean cities, with urbanization rates growing much faster than population. This trend was observed in Barcelona (Catalán

et al., 2008 [

22]), Marseilles and the nearby Rhone valley (Pinson and Thomann, 2001 [

23]), Rome (Munafò

et al., 2010 [

24]) and Athens (Salvati

et al., 2013 [

25]), among others. The diffusion of sparse settlements driven by population de-concentration since the early 1980s has created a mixed landscape around the main cities and is considered a relevant socioeconomic challenge in the Mediterranean region (Alphan, 2003 [

26]; Catalán

et al., 2008 [

22]; Terzi and Bolen, 2009 [

27]; Salvati and Sabbi, 2011 [

28]). According to the projections proposed by United Nations Urbanization Prospects (derived from the website esa.un.org [

29]), urban population will be 72% in Greece, 76% in Italy, 82% in Portugal and France, and 85% in Spain by 2030. Projections highlight the growing pressure for metropolitan urbanization that Southern Europe will experience in the near future.

The key words emerging from rapidly-changing local contexts are diversification, entropy and isolation, among others (Burgel, 2004 [

30]). Contemporary cities in southern Europe take on a polarized spatial structure emphasizing population disparities (Delladetsima, 2006 [

31]; Leontidou

et al., 2007 [

32]). The economic space became fragmented assuming a spatial organization hardly classifiable as “polycentric” (Giannakourou, 2005 [

10]; Maloutas, 2007 [

33]) and with relevant services and infrastructural divides at the local scale (Leontidou, 1990 [

34]; Krumholtz, 1992 [

35]). Long-term trajectories in Mediterranean urbanization—supposedly converging at the regional scale—contrast with patterns and trends in urban expansion which are characteristics of each country and possibly of each city investigated.

The present study proposes an interpretation of “southern” urbanization with less common aspects and more differences at the regional scale. Sprawl is intended as a recent urbanization pattern exemplificative of this challenge, moving from a unifying “Mediterranean” vision to city-specific “growth and change” processes characterizing the southern European urban arena (Kasanko

et al., 2006 [

21]). The cases of Barcelona, Rome and Athens are considered in the present study. These cities share similar territorial characters, showing a unique structure and socioeconomic configuration. Sprawl has adapted to their contexts in different ways depending on historical, cultural and political issues. Exhibiting a regional or national capital role, these cities have hosted competitive events of global importance, such as in the case of Athens and Barcelona with the Olympic Games. A narrative comparison of the recent processes of urban growth reveals how sprawl has occurred at the metropolitan scale and the apparent and latent connections between compact urbanization, land-use and economic structure observed in the three cities.

The article is organized as follows: a comparative framework is proposed in

Section 2 by illustrating the local context in the three cities based on the in-depth analysis of demographic, land-use and socioeconomic indicators derived from official statistics at a disaggregated spatial scale.

Section 3 reframes the specific patterns and processes of sprawl in Mediterranean Europe providing narrative examples of the recent growth observed in the three cities.

Section 4 summarizes and discusses the evidence proposed in our study providing an original interpretation of urban sprawl in Barcelona, Rome and Athens, taken as distinct patterns and processes based on the complex interplay of place-specific territorial and socioeconomic factors. By integrating narrative and quantitative approaches, we provide elements to “reset” the scene of “southern” sprawl revisiting the main socioeconomic drivers of change in contemporary Mediterranean cities.

2. Setting the Scene: A Comparative Analysis of the Socioeconomic Context in the Three Cities

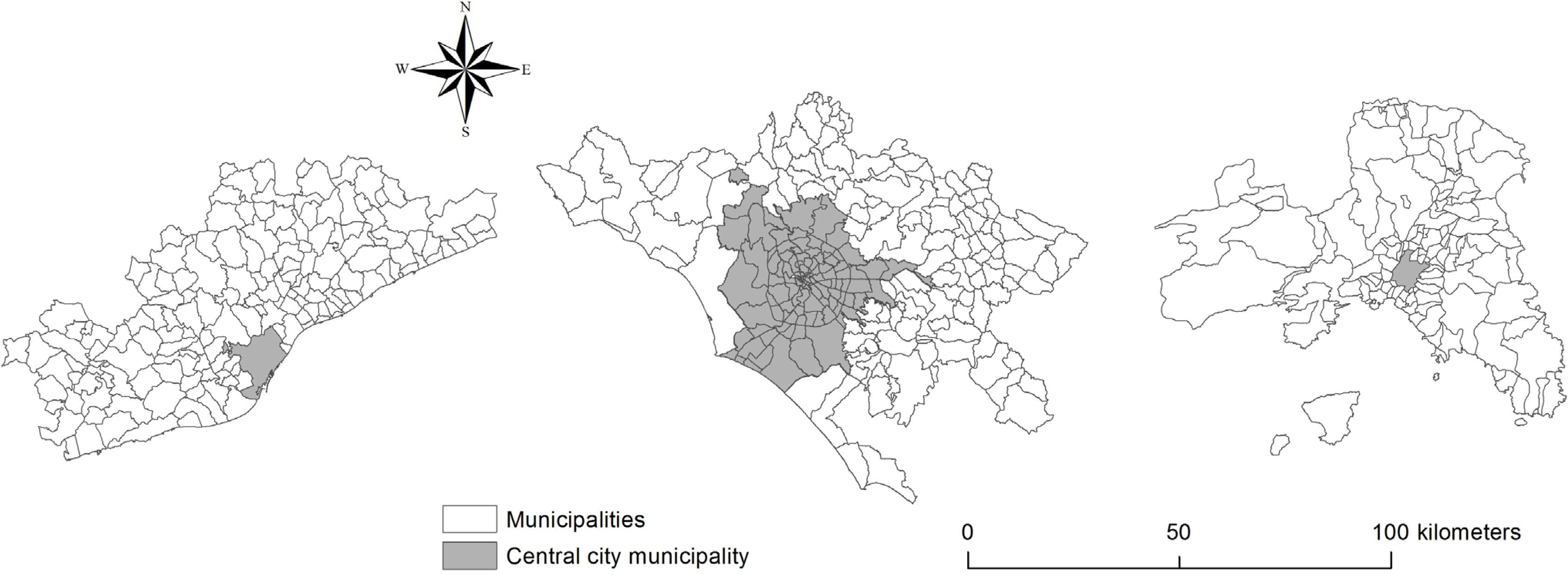

Together with the difficulty in analysing patterns and processes of dispersed urban expansion from the socioeconomic point of view, there is a lack of basic information required to perform this type of analysis at a spatially disaggregated geographical scale. The absence of unifying databases containing homogeneous and relevant diachronic information complicates the comparison between metropolitan areas when identifying different types of sprawl patterns and processes. The present study outlines a comprehensive picture of the recent development of Barcelona, Rome and Athens based on a set of contextual indicators with the aim to assess a variety of socioeconomic issues related with sprawl. We implement a narrative approach based on the simplified analysis of maps and the spatial distribution of indicators derived from official statistics and other data sources, integrated with a bibliographic analysis of recent publications in the field of urban studies in Europe—and especially in Southern Europe. We used local administrative boundaries (namely the NUTS-5 level of the European Territorial Classification of Statistical Units) as the elementary spatial domain of analysis (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Maps of Barcelona (left), Rome (middle) and Athens (right) study areas illustrating the boundaries of local municipalities and the position of the central city.

Figure 1.

Maps of Barcelona (left), Rome (middle) and Athens (right) study areas illustrating the boundaries of local municipalities and the position of the central city.

2.1. The Intimate Pattern of Sprawl: Unravelling Land-Use Patterns

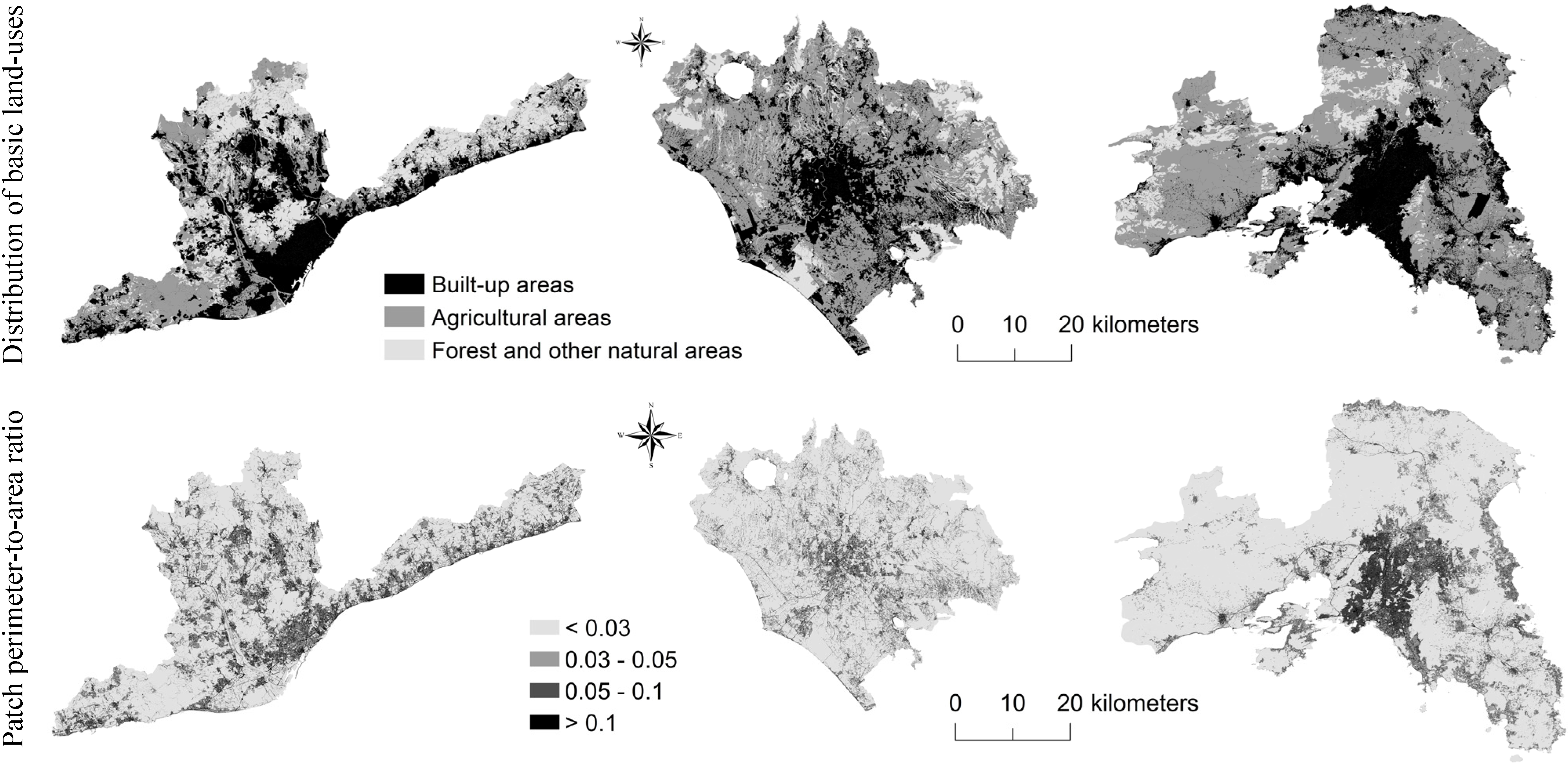

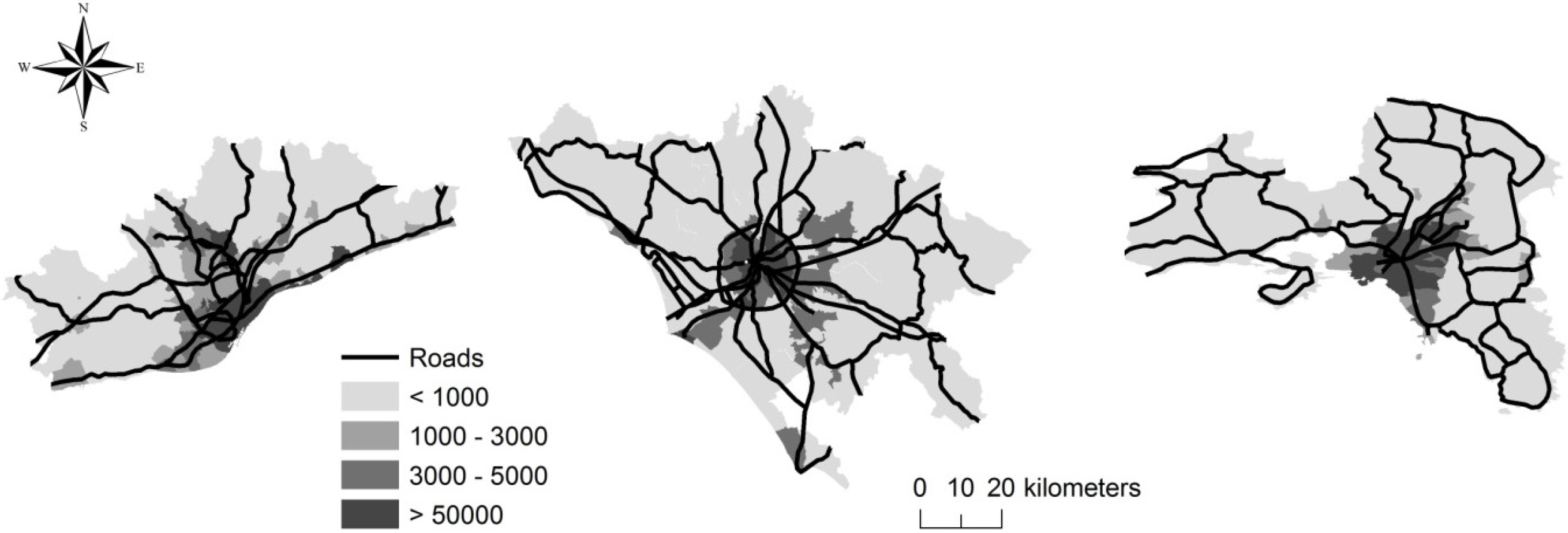

Data on the total surface of the three metropolitan areas and population density are provided in

Table 1 using information derived from the Urban Atlas, an initiative of the European Environment Agency producing high-resolution land-use maps scaled 1:10,000 for a number of metropolitan areas, and official statistics. Metropolitan areas were identified using commuting data from the most recent population census. Land-use maps were elaborated using a nomenclature based on three classes: (i) built-up areas; (ii) cropland and non-forest natural areas and (iii) forests (

Figure 2). The three cities show different morphologies: compact settlements in Athens, semi-dense and discontinuous settlements in Rome and a more aggregated and spatially-balanced urban fabric in Barcelona. A landscape metric (perimeter-to-area ratio, intended as a widely-used shape index) was finally calculated for each land patch and mapped to identify urban districts with higher land fragmentation.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the three metropolitan regions.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the three metropolitan regions.

| City | Surface Area (km2) | Population | Population Density (Inhab/km2) |

|---|

| Barcelona | 3242 | 4,394,412 | 1355 |

| Rome | 5352 | 3,700,424 | 691 |

| Athens | 3025 | 3,724,393 | 1231 |

Figure 2.

Land-use maps in Barcelona (left), Rome (middle) and Athens (right).

Figure 2.

Land-use maps in Barcelona (left), Rome (middle) and Athens (right).

Maps indicate that the spatial distribution of Athens settlements is rather dense and compact; Rome settlements are more dispersed over the metropolitan area while the Barcelona metropolitan structure shows an intermediate pattern of urban expansion. A morphological analysis of the three regions was carried out on the basis of the level of soil sealing due to urbanization (

Figure 3). Soil sealing is one of the major challenges that Europe faces today because it produces negative environmental impacts, reflecting the “footprint” of each city (Salvati and Sabbi, 2011 [

28]). We use a high-resolution map covering the whole of Europe and produced by European Environment Agency referring to the year 2006. The map consists of a raster data set of built-up and non built-up areas including continuous degree of soil sealing based on multi-sensor and bi-temporal, ortho-rectified satellite imagery. The map represents the degree of sealing with a percentage scale from 0 to 100, respectively, from non-urbanized areas to hyper-compact settlements, identifying urban contexts where sealing values are greater than 60%. Impervious surfaces were defined as pavement structures (roads, sidewalks, driveways and parking lots) covered by asphalt, concrete, brick, stone and rooftops.

Table 2 reports the percentage area of each soil sealing class. Maps well illustrate the compactness of Athens settlements, the discontinuity and heterogeneity of Rome settlements and the polarization in high and low density settlements observed in Barcelona.

Figure 3.

Percentage degree of soil sealing in the three cities.

Figure 3.

Percentage degree of soil sealing in the three cities.

Table 2.

Percentage of soil sealing by class in the three cities.

Table 2.

Percentage of soil sealing by class in the three cities.

| Class (%) | Barcelona | Rome | Athens |

|---|

| 0 | 72.0 | 76.5 | 75.4 |

| 1–20 | 9.9 | 10.9 | 8.1 |

| 21–40 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 4.5 |

| 41–60 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| >60 | 9.4 | 4.9 | 8.5 |

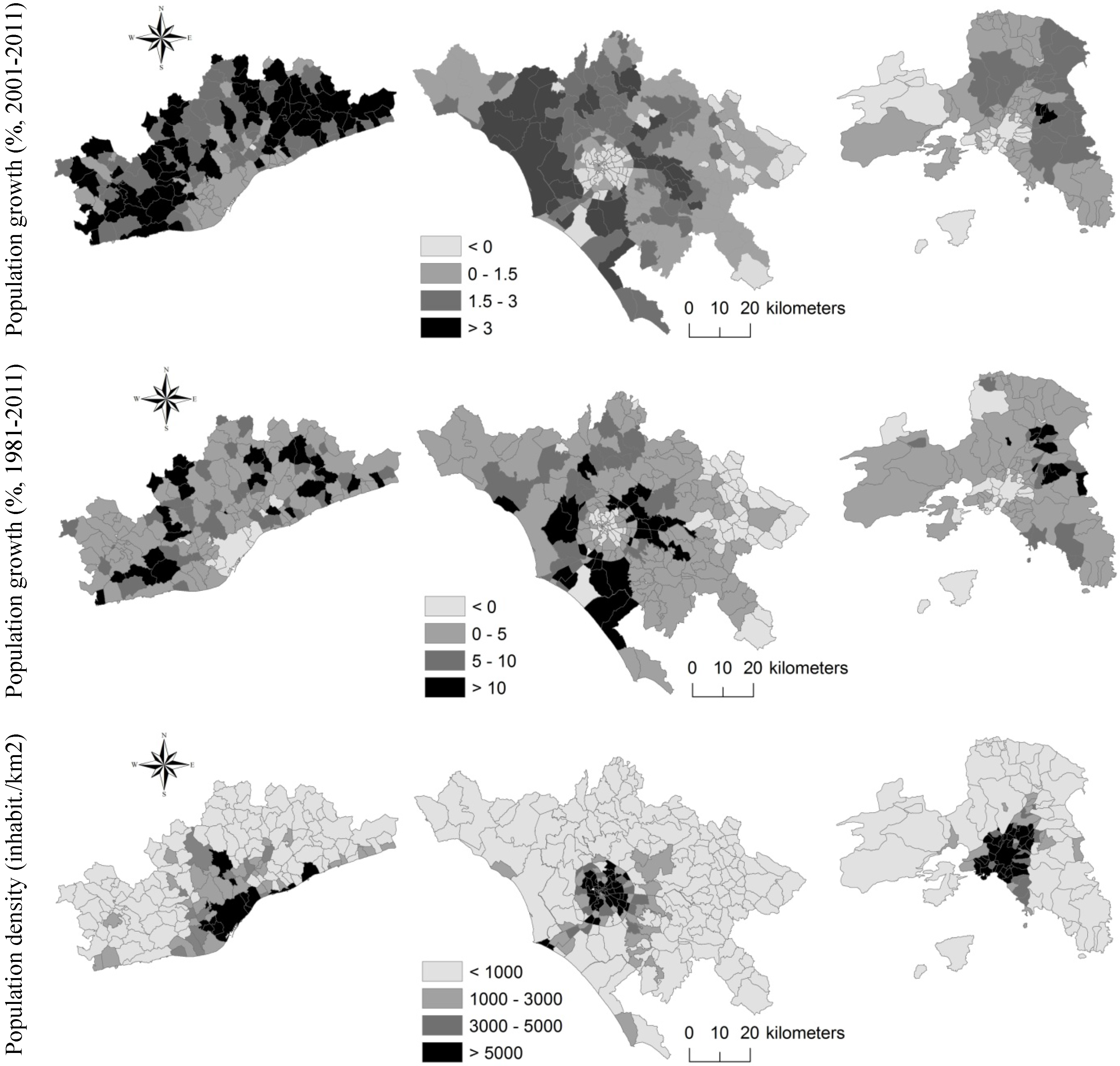

2.2. Population Growth and Urban Expansion

The analysis of population growth may contribute to assess urban sprawl phenomena (Salvati and De Rosa, 2014 [

36]). Three indicators were considered when assessing local-scale urban concentration or dispersion: population growth (i) in the short-term (2001–2011) and (ii) in the long-term (1981–2011) as well as (iii) population density. All indicators were derived from national censuses of population held by the representative National Statistical Office in Spain, Italy and Greece. These indicators allow focusing on the relocation of population in the outer fringe as a consequence of sprawl dynamics (

Figure 4). Maps show that areas surrounding central cities are more attractive because of a growing population in respect to the neighbouring dense areas, contributing to consolidating urban sprawl.

Barcelona experienced diffused population growth in the last decade and a demographic stability with scattered expansion in the last three decades. Population growth in Rome was diffused along radial axes opposed to the inner city, reproducing a fragmented landscape at distances progressively further away from the central districts (Salvati

et al., 2013 [

25]). In the last 30 years, municipalities with the largest increase in resident population were situated in the outer ring of Rome and particularly along coastal areas. The central city showed a moderate decrease in resident population, more pronounced in the last decade. Population growth in Athens was relatively stable over time, although with a moderate decrease in the central city over the last decade, possibly reflecting the opposition between shrinking industrial areas (such as Piraeus and surrounding districts) and sprawling eastern suburbs close to the international airport. Population density discriminates Barcelona and Athens, which are more compact than Rome, dominated by discontinuous settlements.

Figure 4.

Recent population dynamics in the three cities

Figure 4.

Recent population dynamics in the three cities

2.3. Urban Morphology and Infrastructures

City morphology is usually shaped by the interplay between biophysical, socio-demographic, economic, cultural and political contexts. A comparative analysis of urban design features, such as topography, infrastructural networks (e.g., roads, railways) and settlement patterns, contributes to understanding how settlement morphology differs at the regional scale in Barcelona, Rome and Athens. For example, the elevation gradient is an important element shaping urban form and settlement expansion in the Mediterranean region. Rugged topography and sloping landscapes reduce the availability of buildable land, promoting more compact centres and urban growth mainly along the sea coasts or in the main lowland. The three cities were characterized by different elevation profiles as represented in

Figure 5. Athens metropolitan region shows a rugged topography with more than 80% of the surface area classified as hilly or mountainous (>200 m elevation). Rome expanded over the alluvial plain of the Tiber river with buildable land restricted by the Apennine mountain chain east of the central city. Barcelona is in an intermediate condition, with buildable land distributed along the sea coast and in some internal flat areas in correspondence with river valleys of regional importance.

Figure 5.

Classification of local municipalities in each study region based on mean elevation (m).

Figure 5.

Classification of local municipalities in each study region based on mean elevation (m).

The spatial analysis of the main road network allows identifying central cities. We provide maps where the road network overlaps a population density layer (

Figure 6). The analysis highlights three different urban forms. In the case of Barcelona, the road network expands by connecting to other urban centres in the metropolitan area; in the case of Rome, the ring road concentrates the highest population density, which decreased gradually outside; finally, in the case of Athens, population density is low in the metropolitan area, growing in close proximity to Athens and Piraeus, where the roads are intertwined with each other.

Figure 6.

Main road network and population density (inhabitant/km2) in the three cities.

Figure 6.

Main road network and population density (inhabitant/km2) in the three cities.

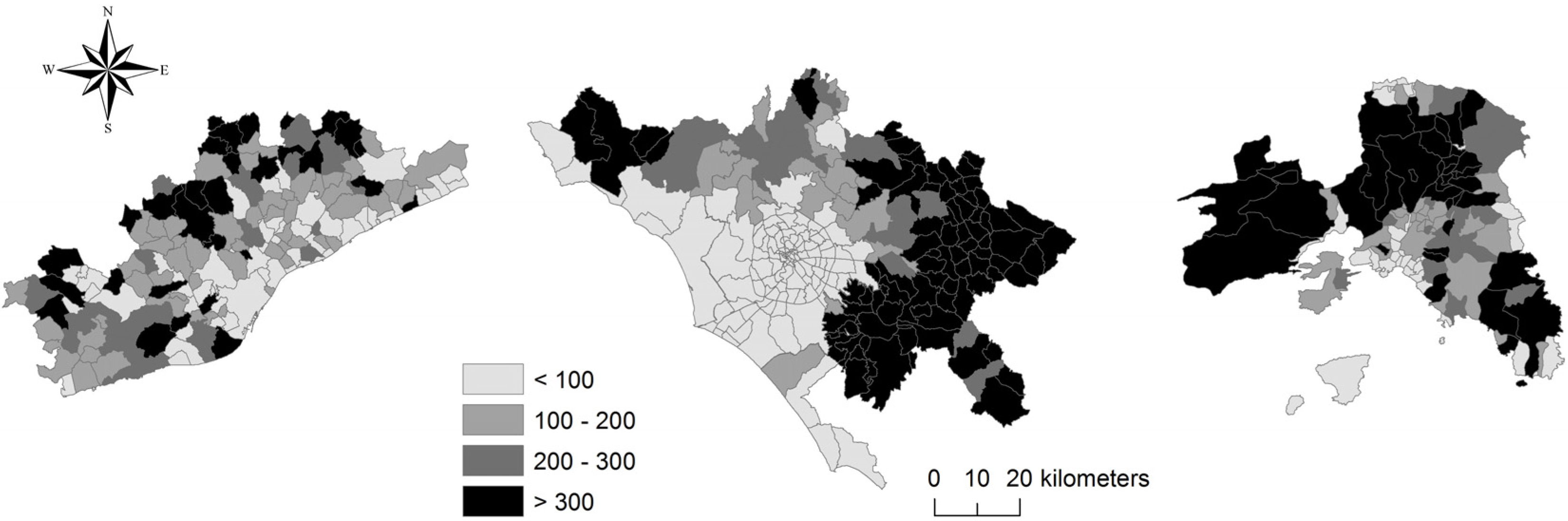

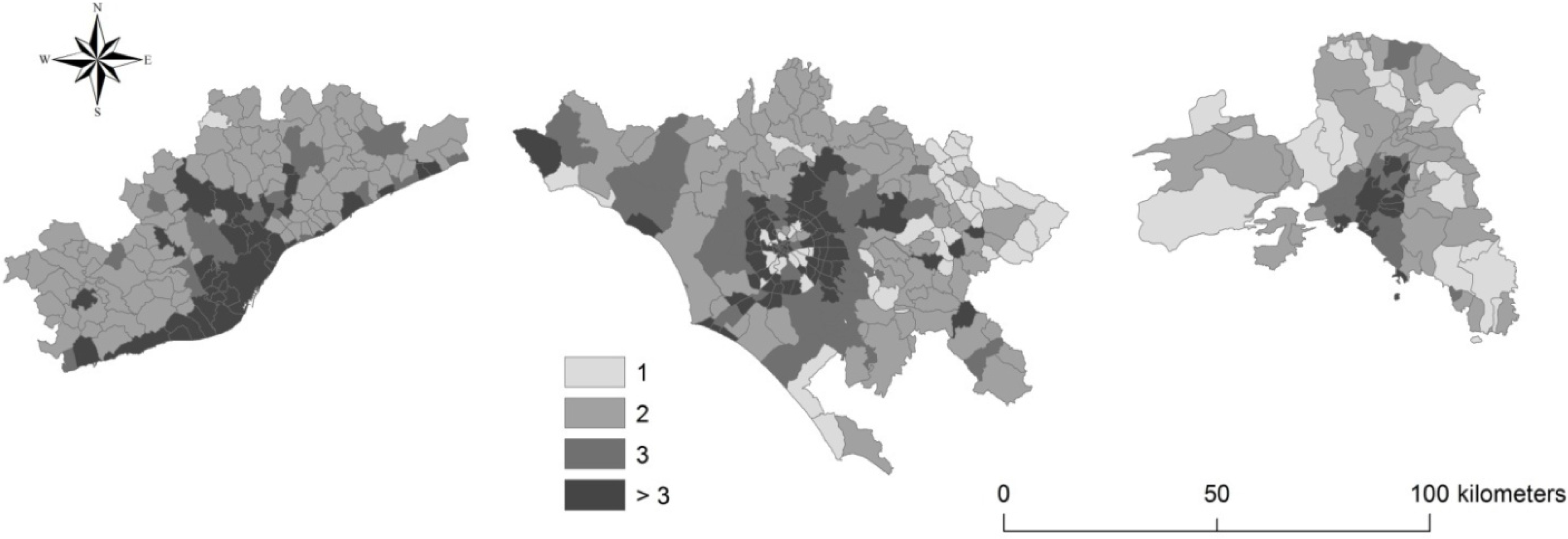

Sprawl is associated with low density settlements composed of individual houses, in contrast to urban realities in which population density is high and buildings host several dwellings together. An indicator which compares the number of dwellings per buildings derived from the national censuses of buildings at the municipal level is proposed in

Figure 7. A value approaching 1 means that for every building there is only one dwelling, or just a household lives there. This indicator is suitable to identify low-density settlements as a characteristic pattern of urban dispersion. Consolidated urban areas have high values of the indicator; the lowest values are observed in peri-urban areas in both Athens and Barcelona and around the central municipality of Rome, confirming the spatial heterogeneity typical of the Italian capital compared to the Spanish and Greek cities.

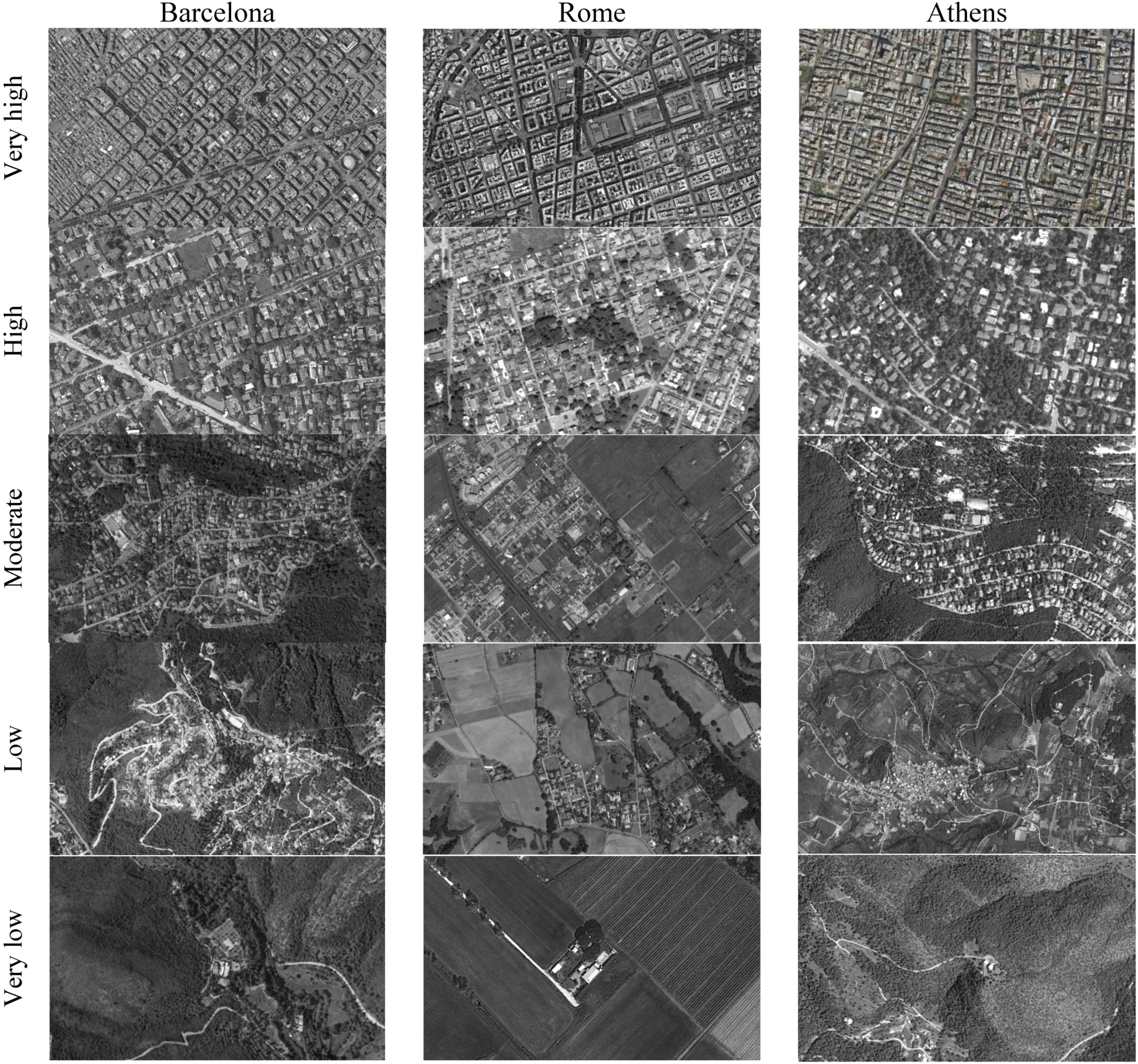

Aerial photographs finally allow understanding the main components of the urban landscape, identifying patterns of sprawl and summarizing the main results derived from the morphological indicators illustrated above. The following pictures (

Figure 8) are intended as a comprehensive sample of urban fabrics, passing from hyper-compact settlements to the most typical contexts of sprawl, responding to the requirements of the socioeconomic indicators analyzed in the following sections.

Figure 7.

Number of dwellings per building in the three cities.

Figure 7.

Number of dwellings per building in the three cities.

Figure 8.

Settlement distribution patterns in the three cities by building density.

Figure 8.

Settlement distribution patterns in the three cities by building density.

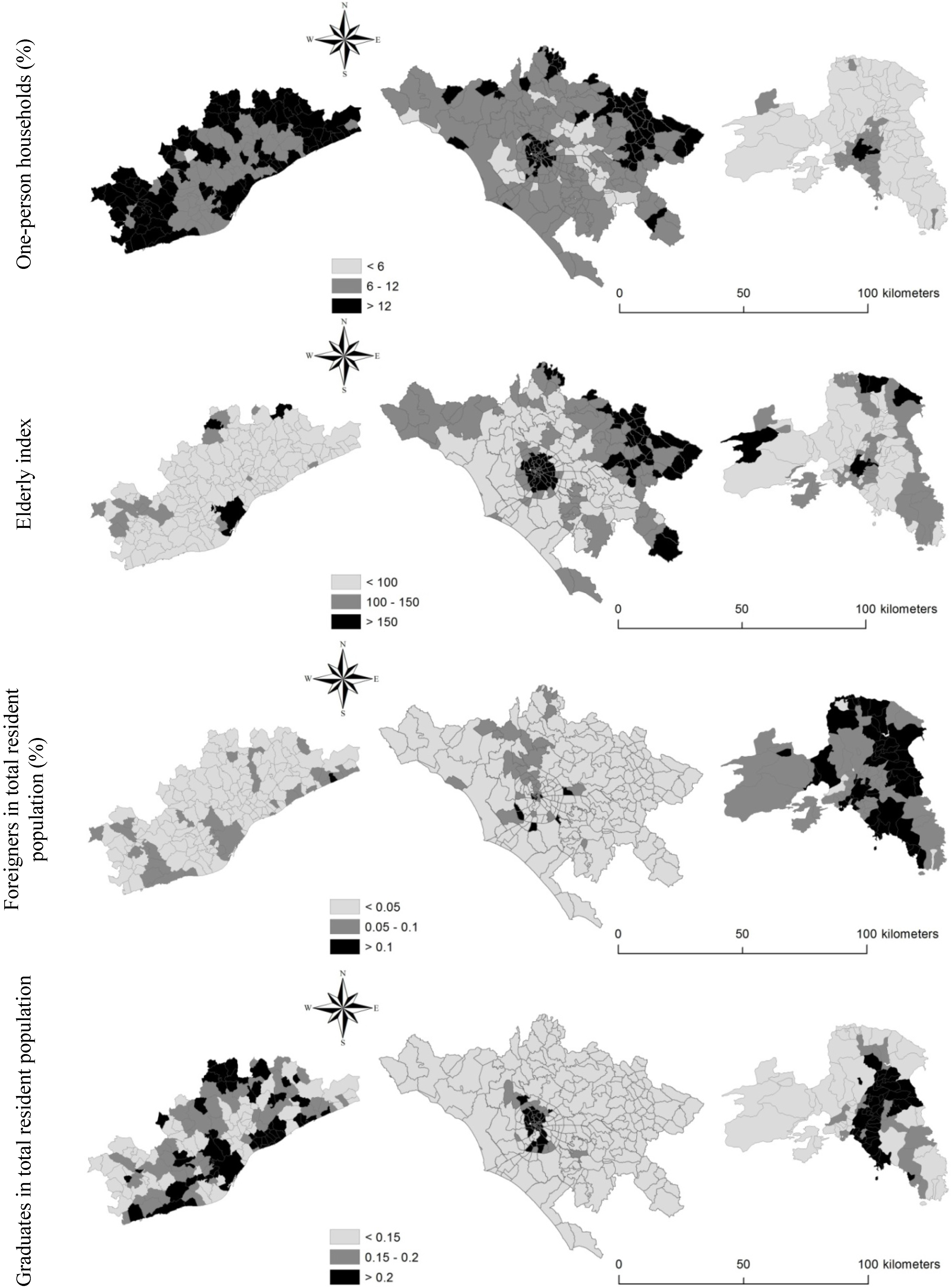

2.4. The Social Context

Four indicators were calculated and mapped at the municipal scale with the aim to assess the dominant social context in the three cities (

Figure 9): (i) percentage of households with one component in the total number of households; (ii) elderly index taken as a proxy for aging processes; (iii) percentage of foreigners (non-native people) in the total resident population; and (iv) percentage of graduates in the total resident population. These indicators were derived from the national censuses of population and allow for a comprehensive picture of the socio-spatial urban structure based on population structure, demographic dynamics and education level, considered as relevant factors of sprawl (Torrens, 2008 [

7]; Gargiulo Morelli and Salvati, 2010 [

8]; Gibelli and Salzano, 2006 [

9]).

The average number of components per family is rather similar in the three cities. Barcelona shows values ranging from 1.7 to 2.8, with prevalence of medium-small households, with 2.4 average components at the metropolitan scale. Athens shows moderately higher values ranging between 2.3 and 4.0, with 3.2 components per family on average. Rome ranks in the middle with average household size amounting to 2.9. In all cities, large households tend to settle in suburban areas. By contrast, one-component households settled prevalently in consolidated urban areas. According to López-i-Villanueva

et al. (2013) [

37], household structure affects housing demand. One-component households (e.g., older people or adults who live alone) are concentrated in urban areas, due to their preference to have more accessibility to services, while large families, usually composed by a couple with two or more children, choose residential neighbourhoods, surrounded by natural amenities and with low population density.

Figure 9 confirms this spatial trend outlining that the highest number of households composed of one person is concentrated in dense urban areas decreasing (more or less) rapidly in the metropolitan region of all cities investigated.

The elderly index completes the picture illustrating a distribution of elder population around the central city of Barcelona, while inland, rural municipalities showed high values of the index, together with some urban districts in Rome. In Athens, population aging was observed in the urban area and, more scattered, in some coastal and inland peri-urban municipalities. The spatial distribution of the elderly index reflects the dominant demographic pattern in the three cities possibly influencing the overall process of sprawl. The proportion of foreign resident population was also discriminating among cities: Athens host the largest foreign population compared with Barcelona and Rome. By contrast, the spatial distribution of graduates (tertiary education) follows a typical urban gradient in all cities, being higher in the central city and decreasing in peri-urban areas. However, differences can be observed between Barcelona and Athens, with a more spatially-polarized distribution of graduates in Athens compared with Barcelona.

Figure 9.

Social indicators in the three cities.

Figure 9.

Social indicators in the three cities.

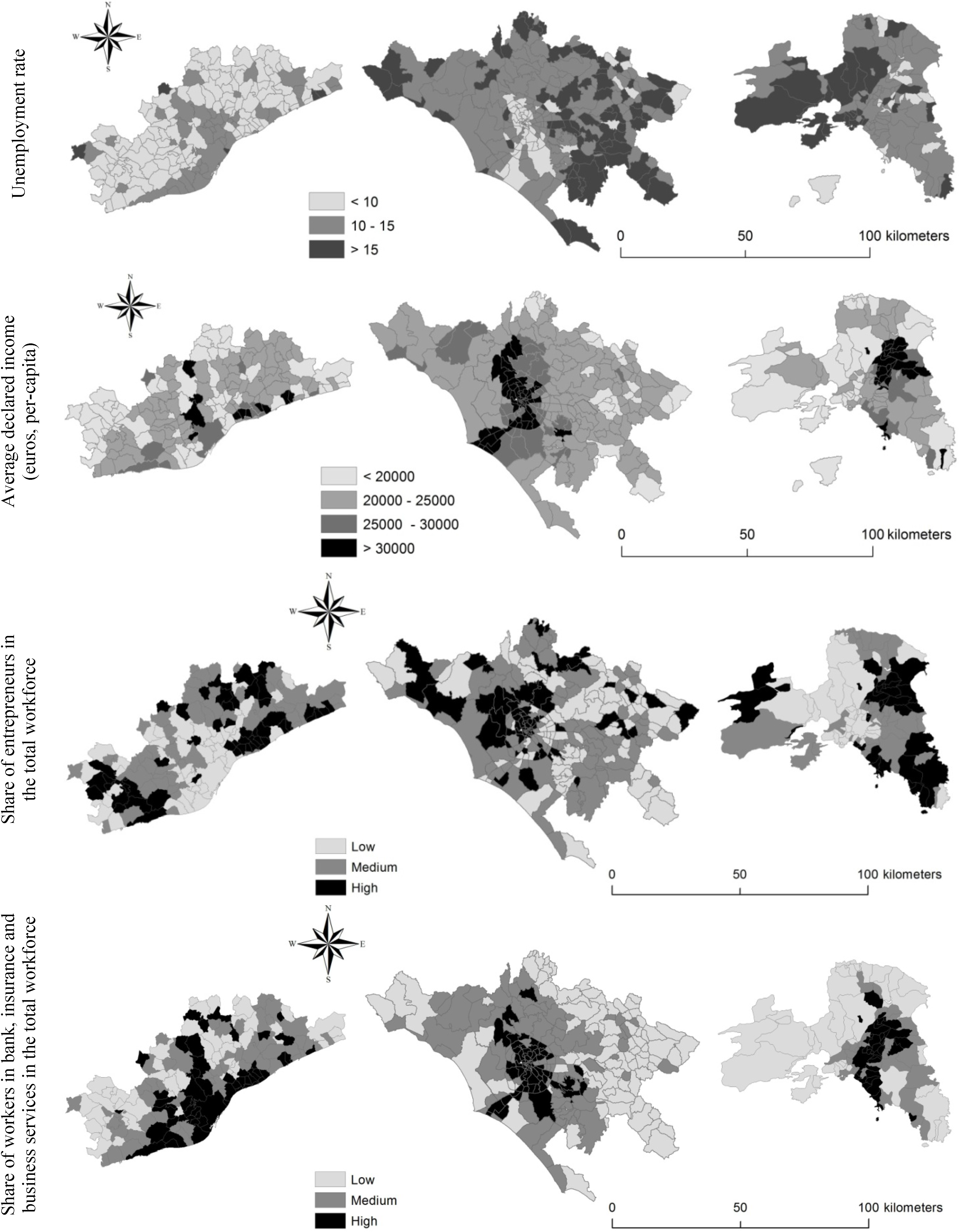

2.5. The Economic Structure

Economic indicators allow identifying the peculiar features and functions that characterize each metropolitan region. The productive structure of the three cities was investigated considering (i) unemployment rate; (ii) average per-head declared income; (iii) share of entrepreneurs in the total resident population; and (iv) share of workers in credit, insurance and business services in the total workforce, as relevant indicators derived from the National Censuses of Population (

Figure 10). The employment rate is the highest in Barcelona (58% on average); in Rome, several municipalities have a low or medium-low employment rate, while in Athens high employment rates can be observed especially in Eastern Attica. Unemployment rate is lower in Barcelona and much higher in Rome while in Attica an east-west boundary was observed with unemployed population concentrated in the western industrial districts.

Together with employment and unemployment rates, declared income is a key indicator when assessing the socioeconomic context influencing sprawl in Mediterranean cities. In Barcelona, the municipalities with the highest income (>25,000 euros per-head) are situated close to the inner city or along the sea coast; the municipality of Barcelona has intermediate values of per-head declared income. In Rome, the highest incomes are concentrated around the consolidated city expanding along the coast. In Athens, the highest incomes were found in the eastern part of the region reflecting socioeconomic disparities between western and eastern districts.

Barcelona shows a relatively high density of entrepreneurs settled in the urban area and in some suburban municipalities. In Rome, entrepreneurs were concentrated in suburban settlements especially along the sea coast. The maximum value of the indicator reaches 0.5 in Rome and declines to 0.2 and 0.3, respectively, in Athens and Barcelona. Entrepreneurs concentrate in the eastern districts of Athens possibly indicating moderate class segregation. A similar distribution was observed for the percentage of workers in banking and insurance services in the total workforce. In the case for Barcelona, the highest values of the indicator were found in coastal municipalities with high tourism concentration, real-estate activities and second-home expansion. Workers in banking and insurance services were not concentrated in the inner city while being rather dispersed in the peri-urban region. In Athens, the eastern district attracts the highest percentage of workers in financial services in respect to the remaining metropolitan districts.

Figure 10.

Economic indicators in the three cities.

Figure 10.

Economic indicators in the three cities.

4. Discussion: Re-Setting the Scene of “Southern” Sprawl?

Barcelona, Rome and Athens have maintained their typical configuration as southern European cities; however, in recent years, these compact cities sprawled into their surrounding areas. It is from that moment that metropolitan areas outside urban boundaries began to play a leading role in the Mediterranean urban arena. The pervasiveness of sprawl is then demonstrable through the use of multiple indicators which allow a comprehensive and comparative profiling of the three cities. Our analysis shows how socioeconomic structures are divergent in Barcelona, Rome and Athens. Sprawl has occurred in each of the three contexts but has adapted in different ways, following the dominant economic and social forces. The combination of various contextual factors has promoted the development of new paths of dispersed urbanization (European Environment Agency, 2006 [

20]). Contemporary cities expanding into metropolitan regions are destined to emerge with a competitive and innovative self-image (Longhi and Musolesi, 2007 [

54]; Turok and Mykhnenko, 2007 [

55]; Schneider and Woodcock, 2008 [

56]; Fregolent and Tonin, 2013 [

57]). For example, Barcelona and Athens were promoted as places of mega-events, such as the Olympic Games (Leontidou

et al., 2007 [

32]). In some ways, the Games acted as a “catalyst” for the reorientation of the space policy towards the improvement of the urban landscape (Essex and Chalkley, 1998 [

58]). However, even in this case, the two cities differ because, the urban context of Barcelona benefited greatly from the Games (Chen and Spaans, 2009 [

59]) while the reverse applies to the Athens’ case. More in general, cities have invested in their own territory in order to appear attractive and to improve place competitiveness (Chorianopoulos

et al., 2010 [

49]; Chorianopoulos

et al., 2014 [

60]). However, this trend was rather uncertain in the last decade due to the impact of recession (Kaika, 2012 [

61]; Leontidou, 2014 [

62]; Vradis, 2014 [

63]). Moreover, especially in Rome and Athens, pre-crisis investments were dispersed throughout the metropolitan area (Richardson and Chang-Hee, 2004 [

64]; Bruegmann, 2005 [

15]; Phelps

et al., 2006 [

48]; Catalán

et al., 2008 [

22]), promoting suburban lifestyles—although with a leapfrog spatial pattern (Durà-Guimera, 2003 [

39]; Muñoz, 2003 [

42]; Salvati

et al., 2013 [

25]).

Although Barcelona, Rome and Athens experienced different urbanization paths in the last decades, these cities have all seen the growth of dispersed settlements, driven by informal settlements and real-estate speculation. The present study suggests that sprawl outcomes are strongly associated with both economic and social issues at local scale and are influenced by territorial factors acting at wider scales. Territorial dynamics have indeed shaped the economic structure of the three cities: Barcelona’s polycentric structure reflects the consolidation of urban sub-centres scattered around the central city; the metropolitan area of Rome is more entropic and morphologically “scattered”, outlining the low-density settlement growth up to the 1980s (Krumholz, 1992 [

35]; Salvati and De Rosa, 2014 [

36]); finally, Athens maintains its role as capital city consolidating a typical mono-centric form, despite the presence of specific areas destined to low-density settlements (Leontidou, 1990 [

34]; Kourliouros, 1997 [

52]; Couch

et al., 2007 [

4]). To summarize, sprawl phenomena in the study areas are mainly related to (i) changes in the use of land destined for low-density residential settlements; (ii) changes in urban lifestyles towards social homogenization; (iii) a moderate loss of economic attractiveness of inner cities partly counterbalanced with a gaining importance of sub-centres (e.g., Catalàn

et al., 2008 [

22]; Chorianopoulos

et al., 2010 [

49]; Munafò

et al., 2010 [

24]).

Settlement dispersion has led to economic polarization and social homogenization (Pacione, 2003 [

65]; Leontidou, 1996 [

66]; Beriatos and Gospodini, 2004 [

53]). Socio-spatial disparities had also a negative impact on local cohesion and sense of belonging to the community, considered as one of the outcomes of sprawl (Gibelli and Salzano, 2006 [

9]). In fact, the creation of settlements even more socially polarized may result from economic disparities linked to recessionary times (Vidal, Domènech and Saurí, 2011 [

67]). Short-term dynamics have exerted a negative impact on local communities, increasing socio-spatial disparities and urban poverty, exalting the progressive degradation of city centres and enhancing conflicts of native residents with immigrants settled in deprived neighbourhoods (Arapoglou and Sayas, 2009 [

40]; Muñoz, 2003 [

42]; Allegretti and Cellamare, 2009 [

47]). In fact, the impact of the most recent economic crisis was particularly drastic in Athens (Kaika, 2012 [

61]; Leontidou, 2014 [

62]; Vradis, 2014 [

63]) while being moderately less intense—although extensively recognized—in both Italy and Spain (e.g., Garcia, 2010 [

68]; but see also Chorianopoulos

et al., 2014 [

60]).

In order to successfully organize metropolitan areas in the future, investigation should be dedicated to regional/urban planning and sustainable land management. The aim is to work towards a greater containment and management of sprawled urban expansion. In recent years, local governments have proceeded to prepare strategic plans, which aim to administrate the entire metropolitan area and strive towards a truly polycentric development, which reduces the spatial divides, redistributing population and businesses throughout the metropolitan area, strengthening urban centres outside the city (as in the case of Barcelona and Rome) and avoiding social and economic imbalances.

Urbanization patterns are progressively shifting towards individual expansion paths, giving more value to place-specific factors than to regional-scale processes. The recent experience of Barcelona, Rome, Athens and the role of the local socioeconomic context shaping urban growth and socioeconomic disparities are seen as an example of the diverging sprawl patterns observed in Mediterranean Europe. Sustainable management of urban (and non-urban) land is increasingly required to consider the diversity of processes of urban dispersion as an inherent element of urban complexity, based on the intimate and spatially-varying relationship between city morphology and functions. A comprehensive perspective on urban sprawl—incorporating economic, social, political and cultural issues—may shed more light on the recent transformations of Mediterranean cities, before and, possibly, after recession. Based on our findings and the results of previous studies, further investigation focusing on the impact of economic crisis on short-term sprawl dynamics is required, privileging a comparative approach that covers different cases in the Mediterranean region.