3. Results

It must be acknowledged that the regional finances of these regions vary greatly in their qualitative and quantitative state. The study revealed that most scientific works devoted to this issue examine the following aspects. For example, in their work, researchers address the issue of the uniform distribution of tax payments throughout the fiscal year to the national and local budgets, which influences the efficient use of budget funds (

Issatayeva & Adambekova, 2016). However, above all, attention should be paid to the dynamics of local budget revenue structure and their differences when compared between regions (

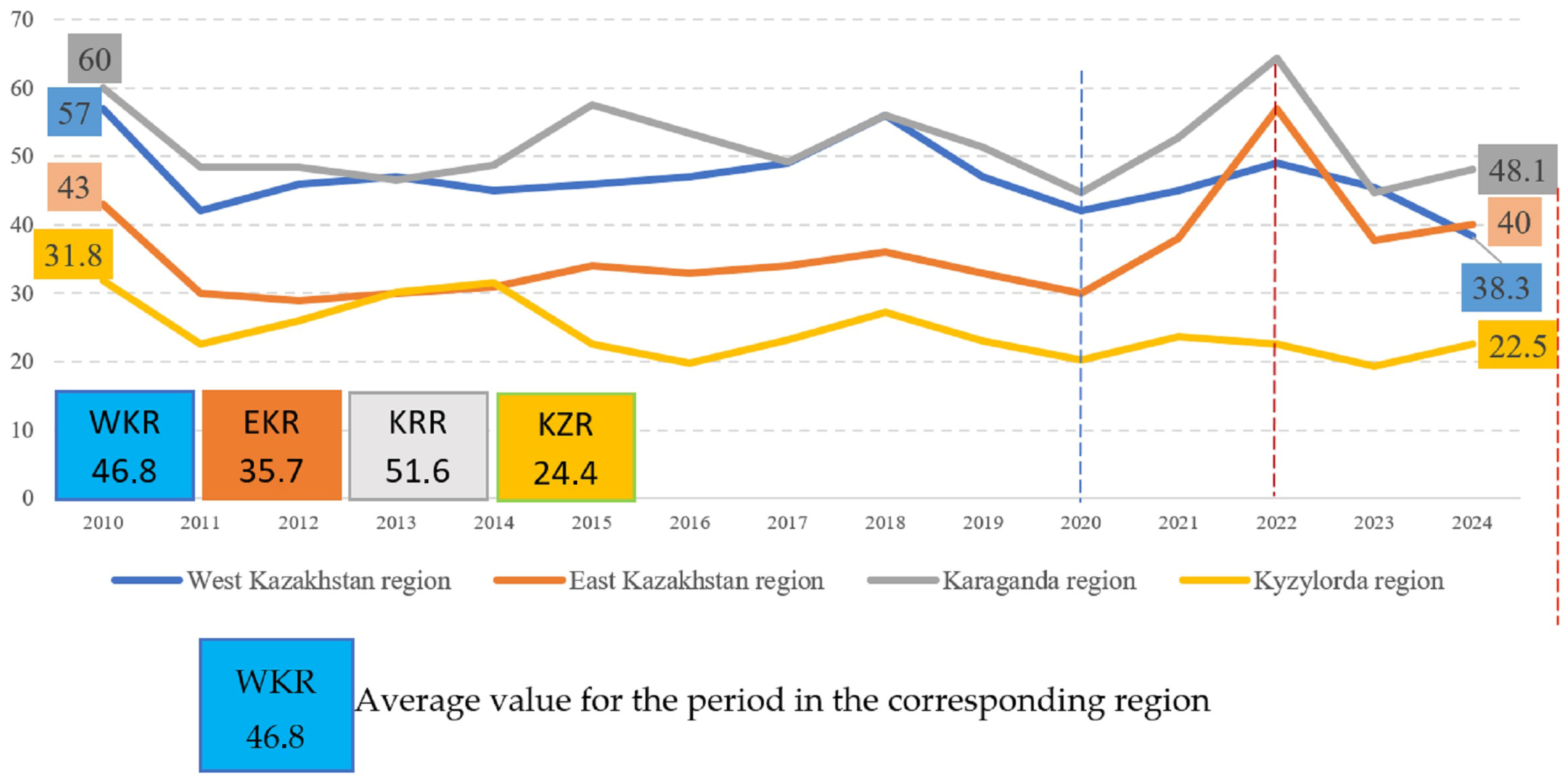

Figure 4).

Analysis of the data presented in

Figure 4 reveals that the growth dynamics of local budget revenues (right scale) in the East Kazakhstan Region lag behind the average growth rate by almost two times: 8.5% in the East Kazakhstan Region and 16% in the West Kazakhstan Region. Furthermore, while the West Kazakhstan Region experienced negative growth three times in 11 years, the East Kazakhstan Region experienced negative growth four times. Furthermore, the West Kazakhstan Region experienced growth rates exceeding 20% seven times out of 11, while the East Kazakhstan Region experienced growth rates exceeding 20% only twice. The share of tax revenues in the local budget structure of these regions also differs. For example, the East Kazakhstan Region lags behind the average share of tax revenues by a quarter: 40.8% in the West Kazakhstan Region, and 30% in the East Kazakhstan Region. Moreover, the highest level of tax revenue was recorded in the West Kazakhstan Region in 2018 at 48.4%, while in the East Kazakhstan Region, it was 37% in 2024 (in the West Kazakhstan Region in 2024—37.2%). The share of non-tax revenues remains virtually insignificant in both regions—an average of 1%. This indicates that the regions are not effectively taking advantage of opportunities to expand non-tax revenues to the budget. Meanwhile, the share of non-tax revenues in the republican budget is six times higher than in local budgets.

Analysis of the data presented in

Figure 5 reveals that local budget revenue dynamics (right scale) in the Karaganda Region lag slightly behind the average growth rate: 14.6% in the Kyzylorda Region and 13.9% in the Karaganda Region. Furthermore, while the Kyzylorda region experienced negative growth twice in 11 years, the Karaganda Region experienced negative growth only once. Meanwhile, the Kyzylorda region recorded growth rates exceeding 20% three times out of 11, while the Karaganda region recorded them only twice. The share of tax revenues in the local budget structure of these regions also differs. Thus, the Kyzylorda region lags in terms of average share of tax revenues by almost 2.6 times: 18% in the Kyzylorda region and 46% in the Karaganda Region. Moreover, the highest share of tax revenues was recorded in the Kyzylorda region in 2014 at 29%, while in the Karaganda Region, it was 52% in 2015 (in the Kyzylorda region in 2024, it will be 17%, and in the Karaganda Region, it will be 44%). The share of non-tax revenues also remains virtually insignificant in both regions, averaging 1%.

According to experts, the main factors influencing the decline in tax revenues to the budget are the provision of various benefits; a decrease in the number of profitable legal entities; an increase in unprofitable taxpayers; a significant amount of overpayment of corporate income tax, which must be returned to business entities at the beginning of the financial year; an increase in corporate income tax arrears. Significant distortions in the budget process are also explained by the fact that the receipt of corporate income tax mainly comes from large taxpayers using the mechanism of advance payments in November-December of the financial year (

Igibayeva et al., 2020).

According to experts, despite efforts to improve interbudgetary relations, transfer tax revenues to regional budgets (CIT for SMEs), support for local self-government by granting the status of district and village budgets, and increasing the size of transfers to lower-level budgets, trends in the uneven development of regional finances continue to grow (

Sytnyk et al., 2025). The dependence of local budgets is increasing every year: if in 2000 the share of republican budget revenues in state budget revenues was 64%, then in 2023 this share was 80%, even after the transfer of a portion of the CIT to local budgets. Analysts raise the issue of the budgetary capacity of regions in their studies. According to the Budget Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan, budgetary capacity is understood as the cost of public services per unit of recipient of these services, provided at the expense of the relevant budgets (

Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2025). Applied Economics Research Centre’s (AERC) analysts use their own methodology in calculating the budgetary capacity of regions, considering it as the ability of the budget to cover its expenses with its revenues without external assistance. To calculate budget capacity, they used local budget revenues minus transfers from the republican budget as a percentage of local budget expenditures (

Igibayeva et al., 2020). The validity of each of the approaches proposed by the authors requires a comprehensive study. In this paper, the issue of regional budget capacity (as a key aspect of regional financing) is raised in the context of the achievement of sustainable development goals by the regions of Kazakhstan. In modern studies, the sustainability of regional development is assessed from the perspective of demonstrating the regions’ commitment to achieving sustainable development goals and managing the risks associated with this process. This task poses even greater questions for regional governing bodies. On the one hand, it is not only a matter of the ongoing management of regional development, but also a desire to integrate the fundamental principles of sustainable development into this management. On the other hand, there is a need to ensure sufficient resources for all tasks being implemented, including risk management. From this perspective, budget capacity is understood as the adequacy of covering local budget expenditures for sustainable development goals. In this study, the indicator is proposed to be defined as the ratio of the difference between local budget revenues and net transfers to the sum of local budget expenditures minus budget deductions (the calculation of this indicator is presented in

Table 2 using the example of four regions of Kazakhstan) (

Satanbekov et al., 2025). This methodology formed the basis of the National ESG Rating Methodology for assessing the level of regional commitment to achieving sustainable development goals (

A. Adambekova et al., 2025).

The presented data indicate that the lowest level of budgetary capacity is observed in the Kyzylorda region: of every 100 tenge of expenditure financed from the local budget, only 22.5 tenge was provided by the region’s own revenues (of the remaining amount at the region’s disposal). Direct taxes on oil and gas production go to the National Fund, but the remainder, with the exception of VAT, which goes to the national budget, remains at the disposal of the regions. More precisely, the oil and gas sector in Kazakhstan transfers the entire corporate income tax, excess profit tax, mineral extraction tax, rent tax on exports, and additional payments from subsoil users under the Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) directly to the National Fund. To provide additional revenue to the regions, since 2020, revenues from corporate income tax from SMEs (except for large businesses and the oil and gas sector) have been transferred to local budgets. However, this has had no impact on budgetary capacity. It even worsened in 2020 amid quarantine restrictions (

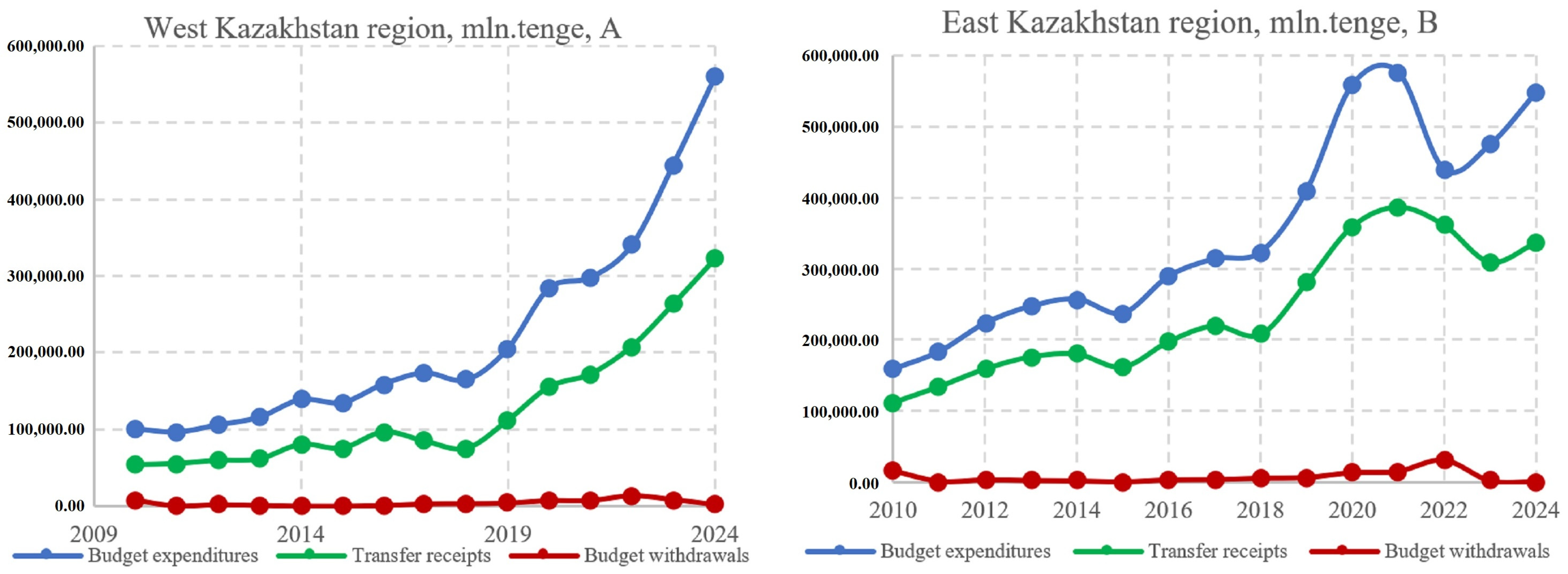

Figure 6). Increased expenditures of local budgets were offset by transfers from the republican budget (

Figure 7).

By 2022, budget capacity had improved slightly in three regions (

Figure 6, growth trends from 2020 to 2022 are marked by the blue and red lines), including due to the corporate income tax. Meanwhile, the Kyzylorda region remains in a downward trend. The study shows that the high centralization of revenues has practically deprived local budgets of the ability to solve their regional problems. Of course, the government strives to evenly distribute transfers from the national budget between the regions to address various issues, but, according to experts, it is precisely this system that has led to significant regional disparities (

Igibayeva et al., 2020). According to the data presented in

Table 1, the Kyzylorda region generates the least tax revenue, only 22%, meaning that almost 80% of the region’s existence depends on national support. Moreover, unfortunately, a common negative trend for all four regions remains the lag behind the average level of budget capacity for the period by the end of 2024. As analysts note, the difference in budget capacity between donor and recipient regions in 2022 is enormous (50% on average) (

Sytnyk et al., 2025). Over the past 20 years, only three of the eight donor regions remain. If current trends continue amid geopolitical risks, centralization will further expand due to the expected decline in revenues from oil, gas, and metal production, and dependence on transfers from the republican budget will only increase. Given the constant reverse transfers from the National Fund to the budget, the issue of reducing the share of taxes and payments directed to the National Fund by some regions is being actively discussed within the academic and business communities. According to analysts, two of the regions we studied, the West Kazakhstan region and the Kyzylorda region, stand to benefit most from this change.

The overall conclusion from the calculations is that the regions (West Kazakhstan region and Kyzylorda region) with oil and gas fields have the opportunity to improve their resilience and resolve many regional problems if at least some of the taxes and payments typically directed to the National Fund remain in the regional budget. In particular, the Karachaganak oil and gas condensate field, one of the largest fields in the world, is located in the West Kazakhstan region. Karachaganak Petroleum Operating B.V. (KPO) annually produces approximately 12–12.5 million tons of liquid hydrocarbons, and there are plans to increase production up to 17.5–18.5 billion cubic meters (

Karachaganak Petroleum Operating B.V., n.d.). The local budget of the region mainly receives individual income tax and social tax from the company; other payments and fees are not so significant. The rest is taken by the National Fund and the republican budget through VAT. As a result, transfers from the republican budget cover almost 60% of the West Kazakhstan region’s budget expenses (

Figure 7). Moreover, in 2014, 2016, 2019, and 2022, the growth rate of transfers to the West Kazakhstan region’s budget outpaced the growth rate of regional expenses by 10% to 15%. This indicates that during the indicated periods, the regions’ need for additional funding grew faster than the regions themselves. A comparison of revenues from the production and sale of goods, works, and services with potential budget payments to the republican budget and the volumes of transfers received will allow us to estimate the regional budget size.

Analysis of the data presented in

Figure 7B demonstrates the dynamics of the local budget in the East Kazakhstan Region. Unlike the West Kazakhstan Region, in this region, the growth rates of expenditures and transfer receipts are virtually identical in their average values (110%). Moreover, the growth rate of transfers to the East Kazakhstan Region budget outpaced the growth rate of regional expenditures by 8% in 2019 and by 17% in 2022. It should be noted that even though the Abay Region was separated in 2022, the volume of the local budget in the East Kazakhstan Region did not decrease in any way either by the end of 2022 (compared to 2021) or by the end of 2019 (while statistical reporting reflects changes in some indicators for these regions since 2019). As a result, transfers from the republican budget cover almost 69% of the East Kazakhstan region’s budget expenditures on average over the entire study period. An analysis of the subvention dependence of the budgets of the Karaganda region and the Kyzylorda region is presented in

Figure 8.

An analysis of the data presented in

Figure 8A demonstrates the dynamics of local budget items in the Karaganda region. Unlike the West Kazakhstan region, the region’s growth rates of expenditures and transfer receipts are virtually identical in their average values (113%). Moreover, the growth rate of transfers to the Karaganda region’s budget outpaced the growth rate of the region’s expenditures, ranging from 10% in 2016, 2017, and 2021 to 14% in 2019.

It should be noted that although the Ulytau Region was separated in 2022, the volume of the local budget of the Karaganda Region did not decrease in any way either by the end of 2022 (compared to 2021) or by the end of 2019 (while statistical reporting reflects changes in some indicators for these regions as early as 2019). Moreover, in 2015 and 2018, growth rates were negative for both expenditures and transfers. As a result, transfers from the republican budget cover almost 52.7% of the Karaganda Region’s budget expenditures on average over the entire study period.

Analysis of the data presented in

Figure 8B demonstrates the dynamics of the local budget items of the Kyzylorda region. Unlike the West Kazakhstan Region, in this region, the growth rates of expenditures and transfer receipts are virtually identical in average values (115%). However, the growth rate of transfers to the Kyzylorda region’s budget outpaced the growth rate of regional expenditures significantly less than in other regions: from 4% in 2014 to 6.8% in 2023. Moreover, in 2015 and 2017, growth rates were negative for both expenditures and transfers. As a result, transfers from the republican budget cover almost 78.7% of the Kyzylorda region’s budget expenditures on average over the entire study period. This situation indicates a lack of financial autonomy for local executive bodies and hinders the search for additional opportunities for low-carbon development.

Comparison of the elasticity indices of gross regional product, tax revenues, and transfers to local budgets by region (

Table 3) will allow for more comprehensive conclusions regarding the actual situation of regional transfer dependence.

An analysis of the presented data revealed that, across regions, significant deviations between the growth rates of GRP, tax revenues, and transfers were observed in the West Kazakhstan Region in the reporting period, and in the Karaganda and Kyzylorda Regions in the previous period. However, it should be noted that only the Kyzylorda Region saw significant growth in transfers in 2022—1.439 times. The fact that transfer growth rates exceed GRP growth rates primarily indicates that the region’s fiscal dependence on the country (the state budget) is growing. This is typical for the West Kazakhstan Region (5 colored zones). Furthermore, it suggests that the region is failing to increase its economic independence, or that state budget funds allocated in the form of transfers are being used ineffectively and are not contributing to GRP growth. Thus, in the Karaganda Region, 4 of 16 indices indicate a similar situation and lead to the same conclusions.

Overall, due to the implementation of anti-crisis programs in 2022–2023, the growth rate of transfers generally outpaced other indicators in the Karaganda and Kyzylorda regions. However, the growth rate of tax revenues lagged behind the growth rate of GRP and transfers throughout almost the entire study period in all regions except the West Kazakhstan region. Thus, the annual growth rate of tax revenues to local budgets averages 23.7% across the republic, while GRP is growing by 13.2% and transfers by 13.1%. Moreover, most regions have generated their budget revenues from tax revenues at the same level year after year over the past five years. It should also be noted that the average annual inflation rate, according to the Bureau of Statistics, is 8.66%, annually reducing the real ratio of tax revenues to regional GRP.

The significantly low share of tax revenues in the budget is primarily due to a decline in these revenues. The following factors have been cited as the causes: the provision of various benefits; a decrease in the number of profitable legal entities; an increase in unprofitable taxpayers; a significant overpayment of corporate income tax, which must be returned to business entities at the beginning of the next financial year; and an increase in corporate income tax arrears.

The regions have hidden reserves for replenishing local budget revenues, which could reduce their dependence on transfers, thereby reducing the burden on the national budget. However, according to experts and regulatory authorities, local executive bodies are not taking sufficient measures to improve the efficiency of tax administration and stimulate the business activity of small and medium-sized businesses, since, regardless of their effectiveness in these areas, targeted transfers continue to flow steadily into local budgets every year. This suggests that the state, by providing such support, discourages regions from expanding their resource base.

The allocation of targeted transfers often occurs without detailed calculation checks and reliable justification, as well as the necessary conclusions and expert opinions. Due to insufficient project development, funds are disbursed untimely. As a result, significant sums accumulate locally and are then redistributed to other activities, creating conditions for financial irregularities. Moreover, an examination of reports on the results of monitoring the effective use of republican budget funds conducted by the Supreme Audit Chamber of the Republic of Kazakhstan raises more than gloomy concerns about the quality of public administration in the regions. Administrators of republican budget programs do not adequately monitor the use of targeted transfers and the achievement of final results. According to experts, their functions are reduced to the mechanical transfer of money to local executive bodies.

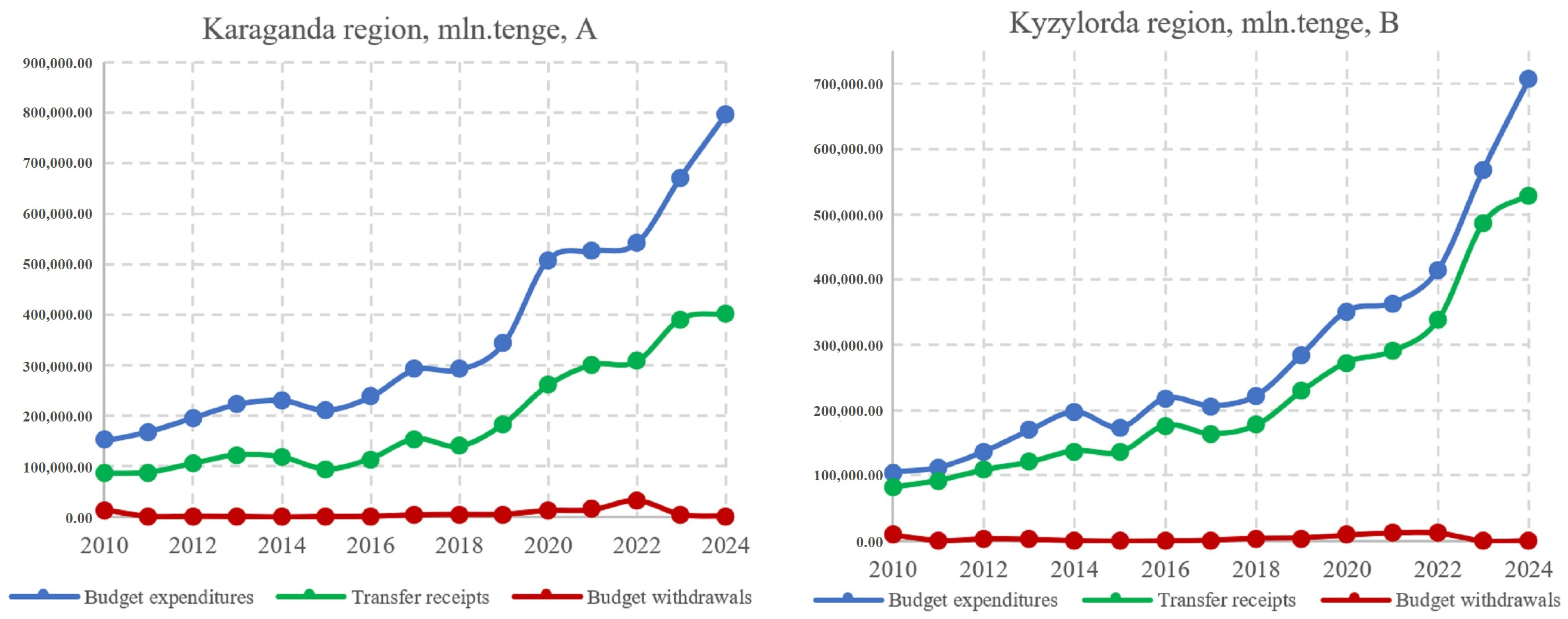

Against this background, the findings are supplemented by an analysis of the financial depth of the regional economy, evaluated through an assessment of the contribution of the relevant funding source to the formation of GRP. This analysis also takes into account the volume of lending by commercial banks operating in specific regions. According to the World Bank, this indicator is used as Domestic credit to the private sector (% of GDP) and to assess the role of the budget—Government revenue (% of GDP) (

Kladakis & Skouralis, 2025;

Menguy, 2025;

WorldBank, n.d.). Transforming the regional economy toward low-carbon development requires more than just “green” finance. It also requires the implementation of green and energy-efficient technologies integrated into a circular economy system, in which all regional production is aimed at decarbonizing production and reducing environmental pollution. This source of regional development financing not only reveals significant regional differences (

Figure 9) but also a significant lag behind leading global economies and places Russia in second place among Central Asian countries in the C5 group (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan).

According to the results of 2024, the leading countries in terms of Domestic Credit to the Private Sector (% of GDP) are the United States (198.2%), Japan (195.8%), China (194.2%), Korea (176.1%), and Switzerland (170.4%) (

WorldBank, n.d.). Clearly, according to global estimates, a level above 100% indicates high credit risks in the economy (

Menguy, 2025). However, in this case, our focus is on the issue of Kazakhstan and its regions’ isolation from the trends of leading global economies. When comparing this indicator in the C5 group, Kazakhstan, with a level of 27.6%, lags behind Uzbekistan (33.2%). This is despite the fact that Kazakh banks are represented by rated private banks (Kaspi, Halyk, Freedom, etc.), while in Uzbekistan, approximately 70% of banking sector assets belong to state-owned banks, which primarily have local ratings. The main explanation is the high growth rate of both the Uzbek economy and the country’s banking sector in recent years, reflecting the ongoing reforms.

Analysis of the data presented in

Figure 9 showed that the Karaganda region leads in terms of loans provided to regional companies by the end of 2024, with 35.2%. This means that 35.2 tenge of commercial bank loans were used to create 100 tenge of regional GRP. Moreover, the average value of this indicator for this region over the study period was 20.6%. The data in the figure indicate that after 2021, the volume of bank participation in financing regional development in the Karaganda region has almost doubled. Overall, the leader in the study period by average value of this indicator is the East Kazakhstan region with 29.8%. The lowest level of this indicator was recorded in the Kyzylorda region with 7.9%, which is almost five times lower than the level of the Karaganda region. However, it should be noted that over 15 years, bank participation in the Kyzylorda region increased from 2.9% to 7.9%. However, the attention of both regional governments and the National Bank of the country should be paid to the problem of a significant gap between regions in the level of bank participation in regional development. Thus, between the leader and other regions, the gap ranges from 2 to 5 times. The low level of this indicator—credit to GRP (Domestic credit to private sector)—indicates that financial institutions are weakly involved, and almost do not participate in financing the real sector of the economy. This may have various causes, some of which are aimed at credit risk management, while others have macro-level implications. But in both cases, these circumstances hinder the progress of regions and regional businesses toward low-carbon production. These causes include strict collateral requirements, high interest rates on loans, regional unevenness in credit resources, the high dependence of small and medium-sized businesses on government support, and the limited availability of long-term loans (

A. Adambekova et al., 2024;

Anessova et al., 2022).

In turn, the Government revenue to GDP indicator is used to assess the role of the state in financing regional development. On the other hand, it is used to assess the effectiveness of fiscal policy. In this study, the main attention is paid to the first aspect. According to the OECD experts (

Semmler et al., 2007), the level of the indicator less than 20% indicates limited participation of the state in the implementation of social programs, the presence of a significant private sector and a low share of the public sector. In world practice, according to the results of 2023, the leaders are France (57%), Finland (56.6%), Belgium (54.6%), and Italy 53.8%. In China, this indicator was at the level of 33.2%, and in the USA—36.6% (

International Monetary Fund, 2025). According to the results of 2024, in Kazakhstan, this indicator was 14.4%. According to the data presented in

Figure 10, the leader in this indicator is the East Kazakhstan region—18.6% (with an average value for the period of 21.1%). The lowest level was recorded in the Karaganda Region at 7.5%, compared to an average of 5.8% for the period. The Karaganda Region, which led in terms of bank participation in regional development, demonstrates a low level, only 11% at the end of 2024, and only 7.9% on average for the period. All these data indicate that regional finances are quite modest in scale. Considering that transfers from the national budget account for 60 to 80% of local budget revenues, it is impossible to speak of regional financial self-sufficiency.

The study showed that differences in development between regions have both objective and subjective causes. In most studies, the authors cite natural, climatic, and geographic differences (

G. Adambekova & Tulegenova, 2022) as objective causes, which in turn determine individual differences in regional infrastructure development. However, when studying the role of regional finances, it is necessary to pay attention to other factors. In particular, researchers cite the uneven distribution of labor and capital, the existing system of inter-budgetary relations, the low level of added value in regional production, which leads to low tax payments, and other factors as subjective causes. Nevertheless, it is important to consider that without the financial autonomy and stability of the regions, the holistic sustainable development of the entire country is impossible. Therefore, the primary task of central and regional governments and administrations is to create conditions for expanding sources of financing for low-carbon regional development.

A lack of resources in local budgets prevents regions from fully fulfilling the functions of the state at the local level. In particular, the poor state of regional infrastructure determines many challenges in both industrial development and logistics. These challenges also include waste and emissions management, water supply, and the development of alternative energy sources. All of the studied regions have poor environmental conditions due to intensive hydrocarbon production, non-ferrous copper mining and processing, and other industries, requiring ongoing environmental protection measures. Therefore, residents’ complaints about poor living conditions, despite the significant wealth in their mineral resources, appear justified (

Alyubaeva, 2025). This necessitates new sources of regional economic growth and, consequently, revenue for local budgets. This requires greater financial independence for the regions to independently implement local initiatives (regional growth areas) through new environmentally friendly projects and the promotion of low-carbon businesses. The concentration of financial and banking resources in the country’s megacities of Almaty (40%) and Astana (18%) leaves regional banks facing the challenges of limited long-term credit resources.

According to the findings of a literature review (

Table 4) of cutting-edge scientific research, an analysis of the structure of local budgets, and the financial depth of regional economies in Kazakhstan’s regions, econometric modeling was conducted using collected data on key socioeconomic and environmental indicators. The collection and substantiation of indicators was based on the approach used in a previously published study (

A. Adambekova et al., 2025). The modeling aimed to test the hypothesis and establish the impact of regional finances on reducing pollutant emissions and the transition of regions to low-carbon development.

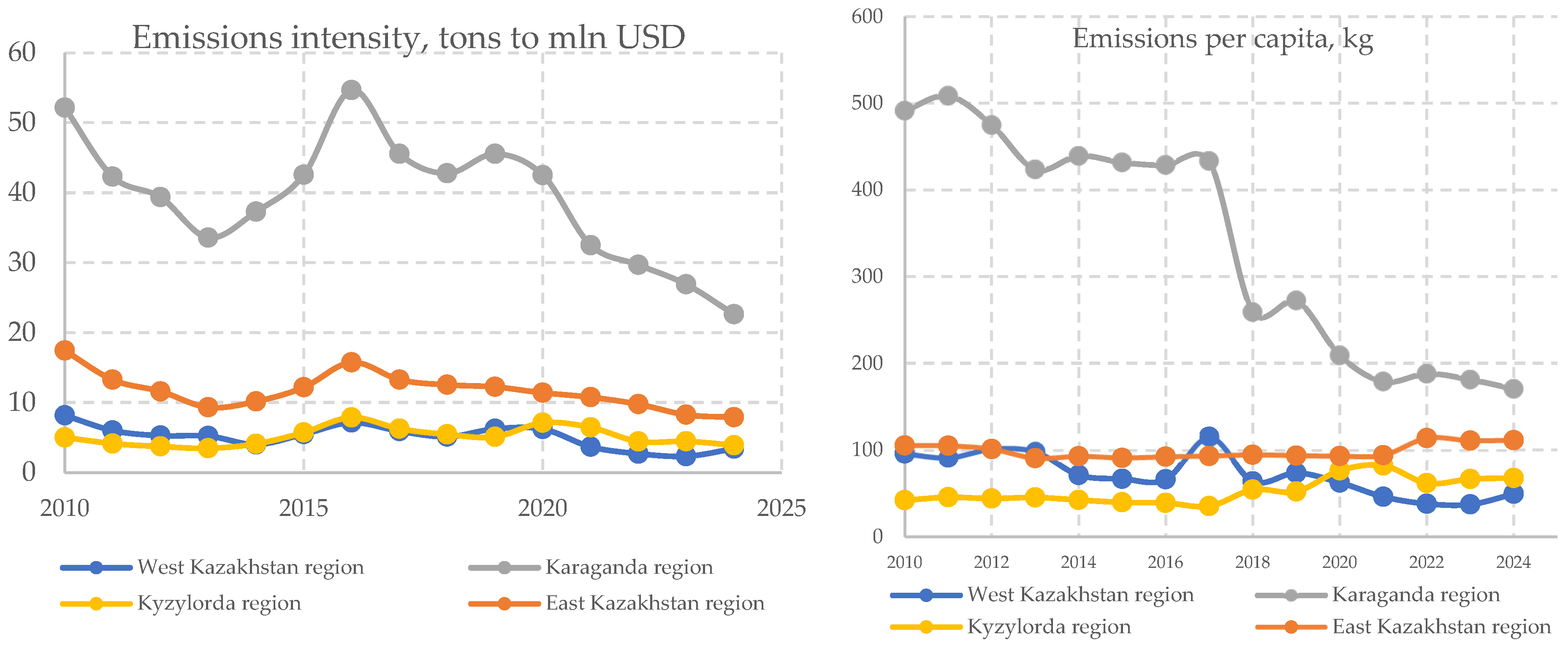

The choice of absolute emissions as the dependent variable was dictated by the purpose of the study—analyzing the relationships between economic factors and environmental burdens, rather than constructing low-carbon transformation trajectories. At the same time, the study acknowledged that emissions are a direct manifestation of environmental pressure, which can be amplified or mitigated through financing. On the other hand, they are measured in specific units (tons of pollution) and reflect the background impact of the economy on the environment. This approach is widely used in empirical environmental economic studies, especially when assessing the influence of social, economic, and financial factors on environmental outcomes. Additionally, to verify the robustness of the results, the Emissions Intensity (Emissions-to-GRP ratio) and Emissions per capita (

Figure 10) indicators were calculated.

The main results remain qualitatively unchanged when emissions are normalized by GRP or population, suggesting that the identified associations are not driven solely by regional scale effects.

In the first stage of modeling, the indicators were tested for their sensitivity to one another (

Appendix A). To construct a model of air pollutant emission factors by region, the indicators identified in the literature review were analyzed (

Table 4). The following variables were excluded from the final model:

- -

x16 (social indicators);

- -

x56, x126 (management indicators);

- -

x96 (financial indicators);

- -

x146, x156 (environmental indicators).

These indicators did not demonstrate a statistically significant or consistent impact on emissions, and their relationship with regional economic dynamics was indirect.

The results of the correlation analysis allowed us to identify a significant group of economic parameters describing industrial activity, output composition, and the investment sector (x26, x36, x46, x76, x86, x106, x116, x136). High correlation coefficient values, ranging from 0.90 to 0.98, indicate a strong linear relationship between these indicators and demonstrate a unified trend in regional economic development (

Appendix A). Simultaneous use of all these indicators in regression analysis is impossible due to a high degree of multicollinearity—adding interdependent factors can increase the estimation error, change the magnitude of the coefficients, and reduce the clarity of the resulting model. However, when selecting the best model structure, it was determined that the x36 (unemployment), x66 (regional budget), and x106 indicators form a reliable and statistically sound model, where each indicator makes a significant contribution and does not duplicate information from each other.

Coefficients:

| | Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | Pr (>|z|) |

| (Intercept) | 179,920 | 129,810 | 1.3860 | 0.16576 |

| x36 | 1456.3 | 741.46 | 1.9641 | 0.04951 * |

| x106 | 0.24533 | 0.034656 | −7.0790 | 0.000000000001452 * |

| x66 | 0.28248 | 0.055012 | 5.1349 | 0.0000002823 * |

| *—sign showing the importance of the variable for the model. |

To analyze how financial indicators influence environmental performance, we employed a random-effects (RE) model using the Amemiya transformation. The choice of the RE model was driven by the need to consider the unique characteristics of regions, which are not always directly measurable. A key step was to validate the specification using the Hausman test (

Table 5). The results (χ

2 = 0.97;

p = 0.808) clearly indicate that the individual effects are uncorrelated with the explanatory variables.

Since the null hypothesis was not rejected (

p = 0.808), we can confidently use the random effects model (

Table 6) as the most adequate and consistent for these purposes.

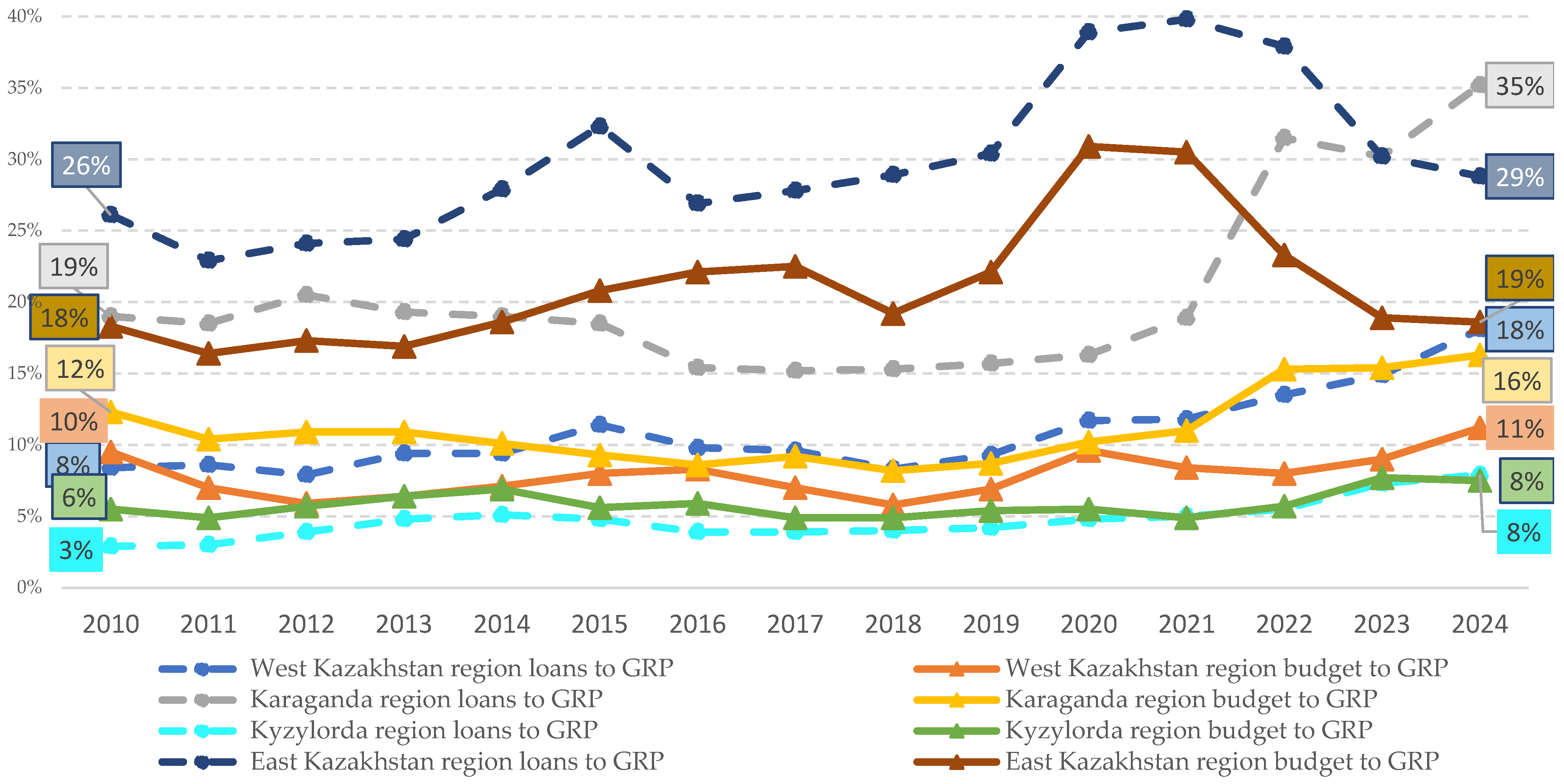

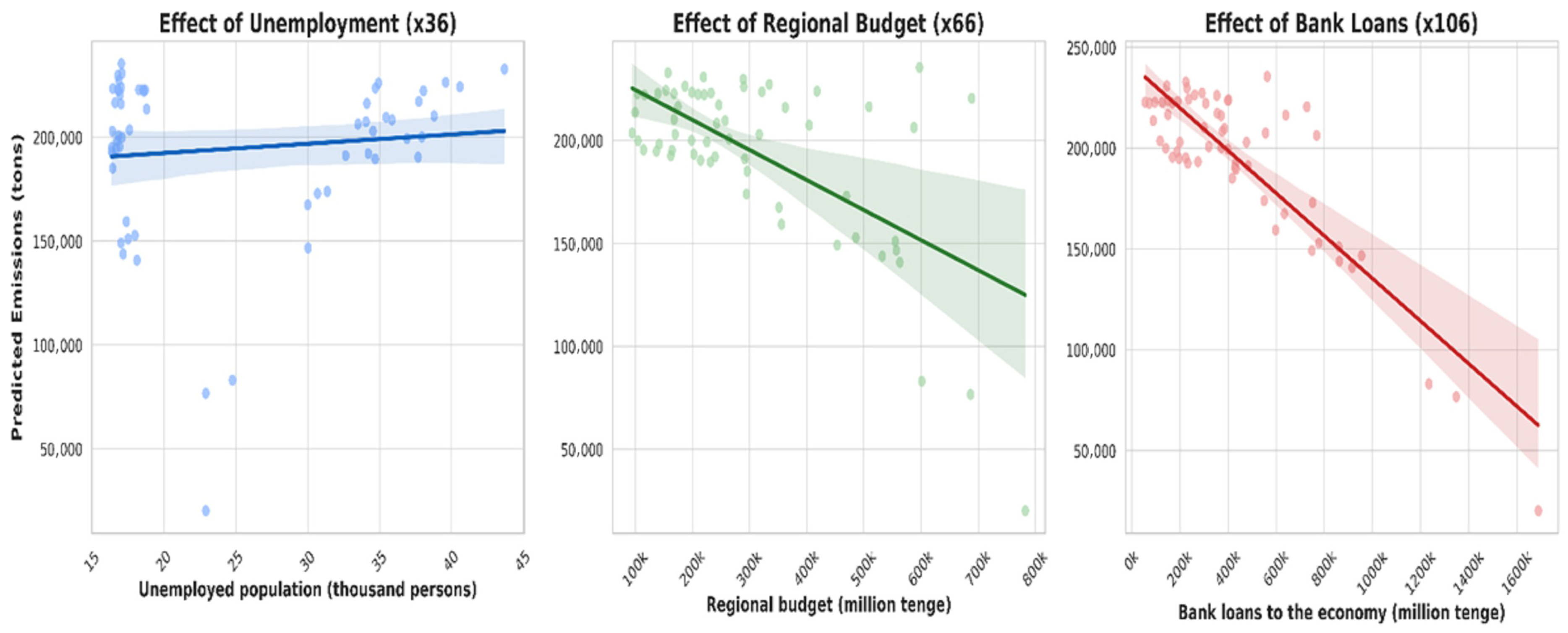

The RE model yielded the following results (R2 = 0.758). The main drivers of emissions growth are bank lending (beta = 1456.3) and fixed capital investment (beta = 0.282), which is expected for a phase of active industrial growth and infrastructure development. The only factor contributing to a reduction in environmental damage was the size of the regional budget (beta = −0.245; p < 0.001). This indicates the effectiveness of budgetary maneuvering in favor of environmental measures. The obtained data emphasize that the current investment model is focused on expanding production, while environmental transformation requires time to demonstrate a statistically significant effect.

Using the resulting equation, a three-dimensional analytical sustainability cube was constructed to visualize and evaluate the environmental, social, governance, and financial impacts of the resulting low-carbon regional development model (

Appendix A). A unique feature of this method is that it shows the simultaneous influence of all factors on the dependent variable, allowing them to be assessed in the presence of their combined impact. This method allows one to supplement the conclusions drawn from modeling, visually expanding their perception. However, it should be recognized that this method, like the quadrant method, is an auxiliary analytical tool and cannot be used separately from the main model when making management decisions. The graph, where the x-axis represents unemployment rates in various regions, shows a prevalent trend toward moderate employment rates (ranging from 15,000 to 35,000 people). However, significant increases in unemployment are accompanied by deviations, indicating a correlation between the social vulnerability of the region and environmental degradation.

The y-axis represents the lending to the regional economy. The volume of loans issued varies significantly, from several hundred thousand to one and a half million tenge. Regions with high lending volumes exhibit reduced negative environmental impacts, as evidenced by decreasing values on the Z-axis and increasing values on the Y-axis. This is confirmed by the results of the regression analysis, which shows a negative impact of loans on the environment (the x106 coefficient is negative).

The Z-axis reflects the environmental impact indicator. Industrial emissions vary significantly, from 30,000 to 150,000 tons and higher, reaching values exceeding 600,000 tons. The highest pollution levels are observed in regions with high unemployment and/or insufficient lending. This observation indicates that social inequality and financial difficulties exacerbate environmental problems.

The color transition from green to red reflects the size of the regional budget. Green markers (small budgets) are often associated with areas of high emissions. Yellow and red markers (larger budgets), on the other hand, predominate in areas with lower environmental impacts, indicating that sufficient funding has a positive relationship on the environment. Therefore, the budget plays a mitigating role, contributing to improved environmental performance in regions.

A three-dimensional model of the relationship between unemployment, lending, and pollution complements the findings that environmental pressure arises in regions experiencing social and economic instability. Regions with limited budgetary resources and access to credit are characterized by the most unfavorable emission indicators. In turn, increased budget revenues and expanded lending resources of regional banks create the preconditions for reducing pollutant emissions. This conclusion is supported by the results of a regression analysis, according to which lending activity has a significant reducing effect on emissions (

Figure 11). Consequently, regions with greater economic investment, including loans and budgetary funds, experience improvements in environmental performance, regardless of their initial unemployment level.

The “partial regression” method allows us to identify the impact of a single variable on the outcome, holding all other factors constant. The graphical display of the partial regression results demonstrates the following: first, the impact of the unemployment rate on fiscal policy and lending activity was controlled; second, the impact of the budget with unemployment and lending indicators was held constant; and third, the impact of loans with the impact of the budget and unemployment was controlled. The resulting data are particularly valuable for regional governments and financial institutions when developing development strategies, as they help determine how fluctuations in specific variables affect emissions while holding the rest of the environment constant. The results of the “partial regression” complements the previously developed three-dimensional representation of the data (the cube method,

Appendix A), offering a statistically justified assessment of the relationships and demonstrating that the negative relationship of budget financing and lending activity on environmental pollution remains significant despite accounting for various factors related to regional characteristics. The next step in the econometric modeling process was the construction of a “Regional Sustainability Quadrants” graph (

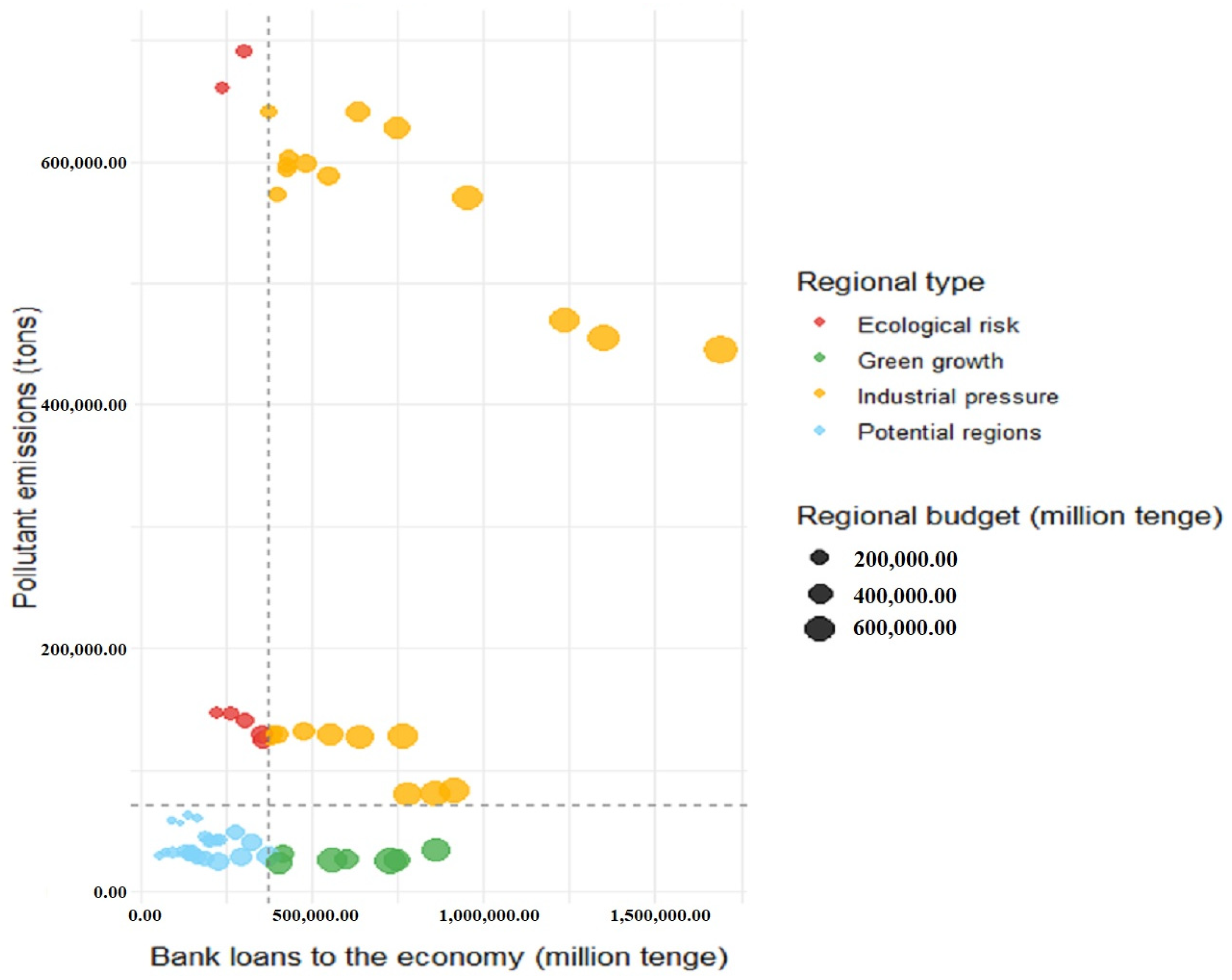

Figure 12). Unlike the cube graph (which allowed for the assessment of multivariate data relationships) and the “partial regression” graph (which allowed for the assessment of the influence of factors after controlling for the model itself), this graph allowed for the classification of regions and supplemented the findings.

The Sustainability Quadrant of Regions allows us to complete the picture of the structural division of Kazakhstan’s territories by level of environmental burden and financial development. The upper left zone (“Ecological Risk”) includes regions with low levels of credit and high emissions, reflecting technological backwardness and a lack of investment activity. The “Industrial Pressure” zone characterizes economically strong but environmentally vulnerable regions, where high levels of production are associated with intense pollution. In contrast, the “Green Growth” and “Potential Regions” categories include regions demonstrating sustainable development—a combination of financial activity, modernization, and low emissions. This approach allows us to consider these criteria as structural patterns for dividing management strategies and identifying sustainability profiles for regional development. This typology confirms that access to financial resources and investment in upgrading production capacity are key determinants of the transition to a low-carbon economy. Four groups of regions were defined based on their characteristics: regions with serious environmental problems and insufficient financial activity (Karaganda region), areas with intensive industrial activity and high levels of lending accompanied by increased emissions (East Kazakhstan region), regions of sustainable development with minimal pollution and significant economic turnover (West Kazakhstan region), and promising zones with low emissions but limited economic development (Kyzylorda region). Using the ‘regional sustainability quadrants’ model, the paper proposed sets of specific recommendations for each identified group (

Table 7).

This classification allows for a deeper understanding of the regression data, demonstrating regional differences that influence the overall patterns revealed by the model. While the regression analysis confirms the overall reduction in emissions due to bank lending and financing from regional budgets, the quadrant analysis details the manifestation of these relationships across different regional categories, providing a more insightful interpretation of the results. The next step was to validate the model using R visualization tools.

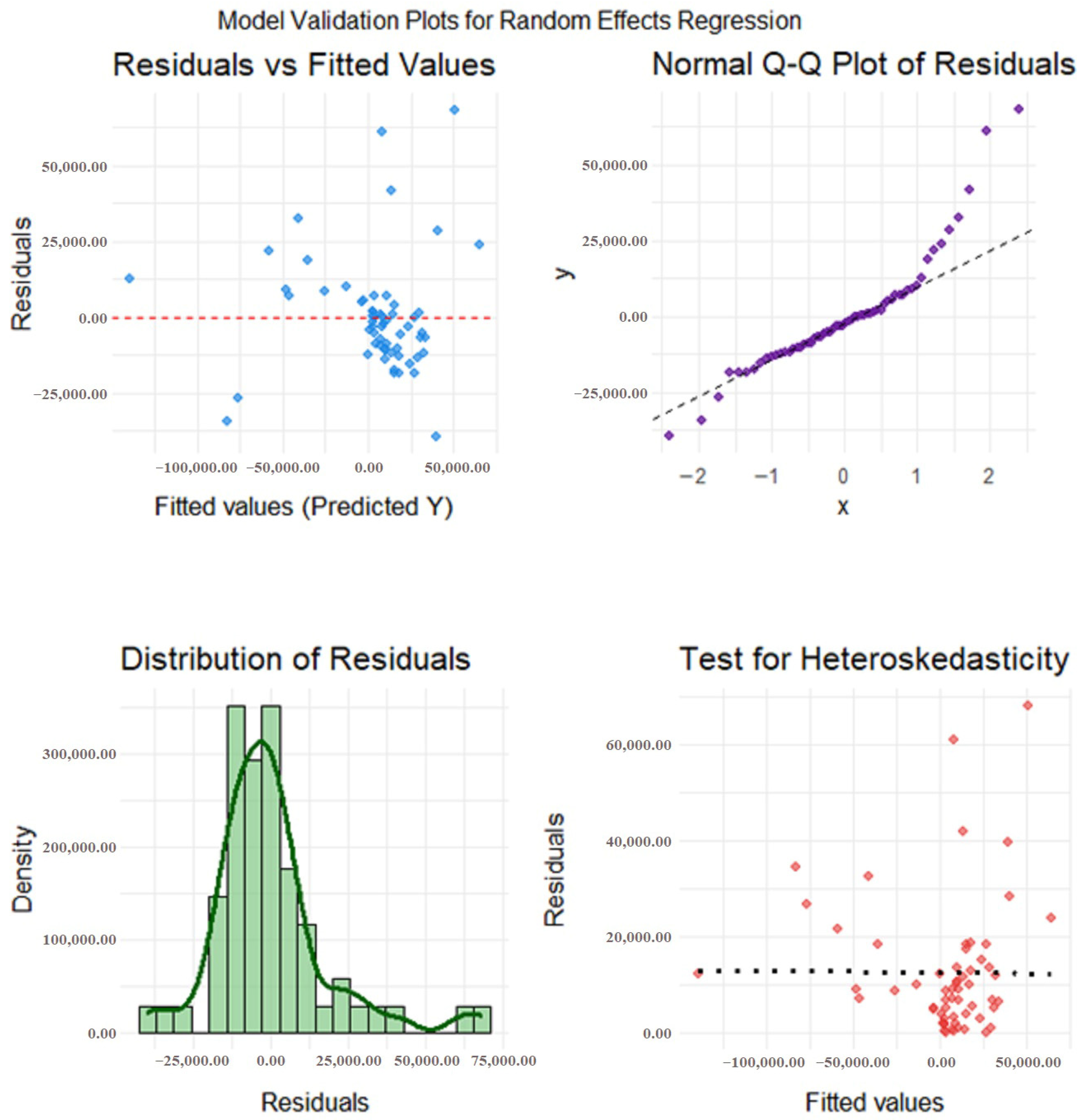

Visual diagnostics of the random effects model confirm its statistical validity (

Figure 13). The residual plot shows no systematic deviations, the QQ plot and histogram indicate a near-normal distribution of the errors, and the heteroscedasticity test revealed no dependence of the residual variance on the predicted values. This allows the model to be considered adequate for analyzing the socio-ecological factors of regional emissions. In the next step, forecasting was performed using R using the constructed model (1).

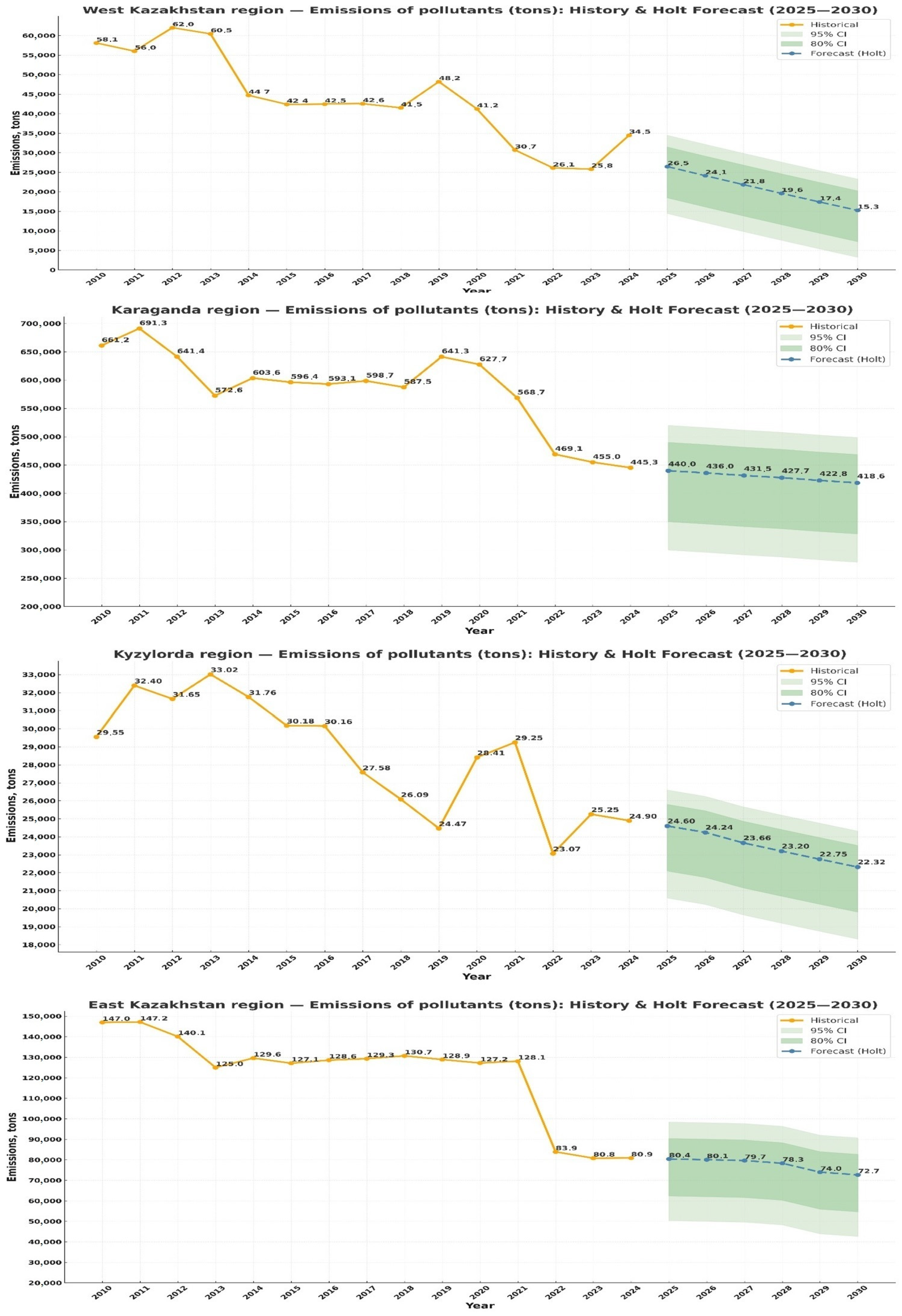

A study of forecast scenarios showed that, given current trends in local budget development and bank lending, the Karaganda and East Kazakhstan regions are at risk of staying at the same level of regional economic growth, with emissions remaining quite high. By 2030, an intermediate stage toward 2050, when Kazakhstan is expected to achieve the stated level of decarbonization of the economy, both regions demonstrate virtually no commitment to reducing emissions. The forecast for the West Kazakhstan and Kyzylorda regions demonstrates greater potential for low-carbon development. Here, the slope of the forecast graph is approximately 15° for the Karaganda region and approximately 17° for the West Kazakhstan region.

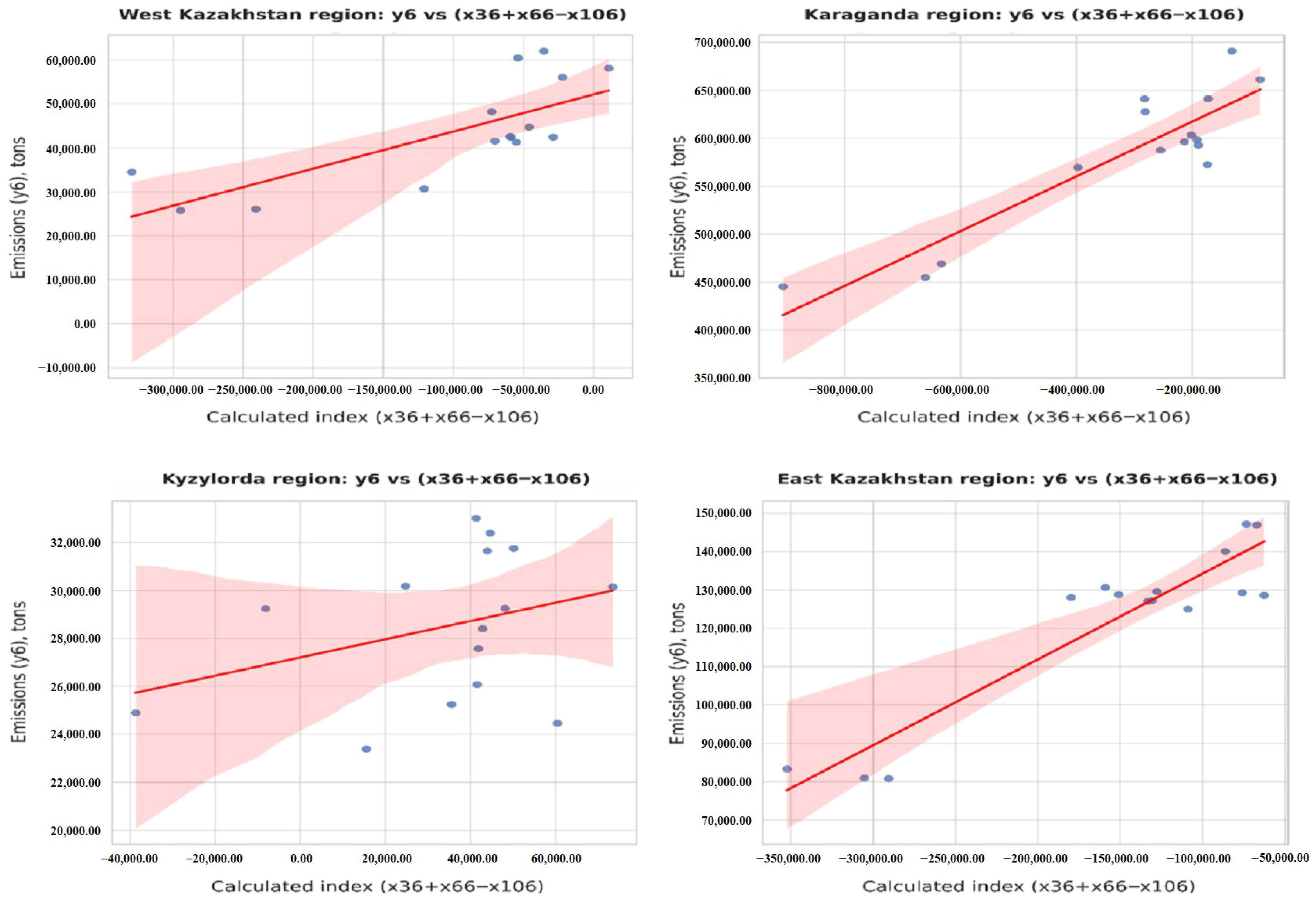

To assess the dynamics of pollutant emissions, an aggregated indicator was constructed based on significant factors: Y = x36 + x66 − x106. It reflects the balance between industrial growth (factors x36, x66) and environmental measures (x106). Comparing the index with actual emissions (y6) by region allows us to identify the extent to which pollution dynamics correspond to the impact of key determinants and in which cases the index serves as an indicator of future changes (

Appendix A). According to the plotted graphs, the Kyzylorda and the West Kazakhstan regions demonstrate the most accurate correspondence between the model and current trends. To clarify the study results, graphs of the dependence of actual pollutant emissions (y6) on the aggregate indicator were constructed (

Figure 14).

Figure 15 shows the dependence of actual pollutant emissions (y6) on the aggregate indicator (x36 + x66 − x106), reflecting the balance of industrial growth and environmental measures. A positive correlation is observed across all regions: an increase in the index is accompanied by an increase in emissions, confirming its explanatory and predictive value for environmental impact analysis.