1. Introduction

South Africa’s wine industry plays a crucial role in the nation’s agricultural export sector, consistently making significant contributions to both domestic and international markets. In 2022, wine exports totalled 386.5 million litres, valued at R10 billion, which was 22% more than the previous year. Domestic consumption was even higher at 452.2 million litres, showing strong local demand. The sector has also made a significant impact on the economy. In 2019, it contributed R55 billion to the economy (

SAWIS, 2021), and by 2024, this figure had risen to R56.5 billion, representing 0.9% of South Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) (

SAWIS, 2024). It supported approximately 270,364 employment opportunities (1.8% of national employment), generated R18.8 billion in labour income, and added R30.3 billion to household incomes. Furthermore, the industry accounted for R80.5 billion in net capital formation and utilisation, alongside R19.3 billion in tax revenue, constituting 1.2% of the total national tax income (

SAWIS, 2024). Globally, South Africa ranks as the eighth-largest wine producer, contributing approximately 4% of the world’s wine output (

SAWIS, 2022). It also ranks as Africa’s leading wine producer and exporter, surpassing other nations such as Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia (

Meloni & Swinnen, 2020;

Abidellaoui, 2023;

Faouzi, 2024), thereby confirming its strategic position within both regional and international trade.

Given the industry’s substantial economic contributions and its strategic importance in trade and employment, this study examines the factors influencing South Africa’s wine exports to selected East African countries, where demand is increasing yet remains under-researched (

WESGRO, 2021;

Kenya Tourism, 2023). This research is supported by South Africa’s comparative advantages, including a Mediterranean climate, diverse grape varietals, and adherence to international standards, which facilitate the production of high-quality grapes and enhance its competitiveness in high-value markets (

Vinpro, 2021;

Wine Tourism, 2023). These conditions have positioned South Africa as the leading wine producer in Africa and as a competitive alternative to established exporters such as France, Italy, and Chile. In addition, favourable production factors have facilitated the development of robust export relationships with developed countries, including the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, and Sweden. Furthermore, China has become an important market due to geopolitical developments, notably trade tensions with Australia (

WESGRO, 2021), which initially created new opportunities for South African exporters. However, recent reports highlight a sustained decline in overall wine demand in China. For instance, wine consumption dropped by 9.3% in 2024, according to the

OIV (

2025), cautioning against relying on the Chinese market as a stable growth driver for South African wine exports. In contrast, regional markets in East Africa remain underexplored, despite evidence suggesting an increasing demand for wine.

Between 2012 and 2021, numerous challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic, disrupted the production and trade of wine. Specifically, wine sales and exports were prohibited during South Africa’s 2020 lockdown (

SAWIS, 2021). Nevertheless, the East African markets demonstrated a swift recovery following the lifting of restrictions. Countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius contributed to the recovery by substantially increasing imports of South African wine (

WESGRO, 2021). For instance, Kenya imported 3.8 million litres, followed by Tanzania with 1.8 million litres and Mauritius with 1.2 million litres (

WESGRO, 2021). Additionally, tourism plays a pivotal role in these nations, substantially contributing to both Gross Domestic Product and employment (

Kenya Tourism, 2023;

WESGRO, 2023), which may, in turn, stimulate demand for wines (

Wani, 2024). Consequently, South African wines are strategically positioned to satisfy this potential demand, particularly within the luxury hospitality sector.

Wine production in South Africa is predominantly concentrated in three provinces: the Northern Cape, Western Cape, and Free State, with the Western Cape in particular leading the way due to its Mediterranean climate. Moreover, the climate of the Western Cape, coupled with well-developed infrastructure and a longstanding tradition of winemaking, establishes it as the epicentre of South Africa’s wine industry and a significant contributor to both national supply and export activities (

Agribook, 2024;

SAWIS, 2024;

Vinerra, 2024). Turning to the importing region, Kenya and Tanzania are among the thirteen countries located on the mainland of East Africa (

African Development Bank, 2024). By contrast, Mauritius, although not part of mainland East Africa, is one of six island nations in the East African region (

World Population Review, 2024). Nevertheless, it is frequently incorporated into regional economic analyses of Eastern and Southern Africa due to its membership in both the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) (

SADC, 2022;

African Regional Integration Index, 2024).

Additionally, the trade relationships between these countries and South Africa are strengthened through their shared membership in regional economic communities. For example, Kenya and Mauritius participate in COMESA, whereas Tanzania and Mauritius are members of SADC, along with South Africa. Furthermore, all three nations, including South Africa, are signatories to the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) (

COMESA, 2024;

SADC, 2024;

African Union Commission, 2025). These trade blocs facilitate intra-African commerce, bolster economic collaboration, and underscore the importance of examining wine export dynamics within this regional framework. The choice of Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius is therefore justified, as not only have these countries demonstrated strong recovery in South African wine imports following COVID-19 disruptions, with Kenya (3.8 million litres), Tanzania (1.8 million litres), and Mauritius (1.2 million) emerging as top regional importers (

WESGRO, 2021), but their tourism-driven economies also generate structural demand for high-value hedonic goods such as wine (

Kenya Tourism, 2023;

WESGRO, 2023). Taken together, their role as leading importers, coupled with their integration into major regional trade blocs, strengthens the rationale for focusing on these markets to better understand the dynamics of South Africa’s wine exports within the broader East African context.

In the literature, however, prominent research has predominantly concentrated on South Africa’s sugar exports within the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) (

Mamashila, 2024a), overall exports within the Southern African Development Community (SADC) (

Mosikari et al., 2016), and fruit exports to West Africa (

Phaleng, 2020). Similarly, other scholarly works have examined broader drivers of agricultural export growth and the associated challenges (

Potelwa et al., 2016;

Seti, 2023;

Mamashila, 2024b). Thus, existing research does not sufficiently explore the specific dynamics that influence the export of value-added products, such as wine, which are affected by factors beyond standard economic indicators. Indeed, in markets such as Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius, the demand for wine is closely tied to tourism and shifting consumer preferences, which differ markedly from the drivers of raw agricultural exports. These unique market conditions necessitate a targeted analysis of wine exports, as traditional models for raw commodities may not fully account for the demand for processed goods. Accordingly, the study is guided by the following research question: What are the key determinants influencing South Africa’s wine exports to emerging East African markets such as Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius? This study addresses this question by examining the trends and determinants of South Africa’s wine exports to selected East African countries, using trend analysis and the gravity model framework, initially developed by

Tinbergen (

1962) and later advanced by

Anderson and van Wincoop (

2003). Guided by the literature, it is hypothesised that importer GDP, population size, FDI inflows, trade openness, and production capacity positively influence South Africa’s wine exports to East African markets.

In contrast, higher import duties, inflation rates, exchange rate appreciation, distance and higher wine prices are expected to inhibit export performance. The gravity model results serve to empirically test these expectations and determine the relative strength of each driver and inhibitor. In doing so, this study generates evidence-based insights that advance academic understanding of value-added agricultural trade in emerging East African markets while also providing practical recommendations to enhance the competitiveness of South African wine in these markets.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides a literature overview, drawing on both international and South African studies to identify the knowledge gap and to highlight the novelty and originality of the study.

Section 3 outlines the methodology, detailing the data sources, preliminary analyses, and the specification of the gravity model.

Section 4 presents empirical results, including the trend analysis, descriptive statistics, correlation and multicollinearity tests, model selection outcomes, gravity model estimates, and robustness checks.

Section 5 interprets these results, situating them within the context of previous findings and discussing their implications for the dynamics of wine exports. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper by highlighting the study’s contributions, practical and policy implications, intended beneficiaries, limitations, and avenues for future research.

2. Literature Overview

2.1. Review of International and National Studies

Both international and South African analyses concerning agricultural export performance have consistently underscored the significance of macroeconomic conditions, production capacities, trade policies, and structural determinants in influencing export outcomes across nations. Regarding global studies,

Iskandar et al. (

2012) investigated Indonesia’s cinnamon exports to the United States from 1998 to 2010, discovering that export volumes were highly responsive to domestic prices, lagged export values, and fluctuations in the exchange rate, thereby highlighting the crucial role of currency valuation and pricing strategies in shaping trade flows. Similarly,

Boansi et al. (

2014) examined Ghana’s fresh pineapple exports, demonstrating that although export values increased in response to higher prices, export volumes exhibited less responsiveness. Their research emphasised the necessity of improving production conditions and enhancing competitiveness rather than relying solely on price incentives. Furthermore,

Tang (

2018) illustrated, in the context of Mauritius, that export sophistication, preferential trade agreements, and historical connections have a positive influence on bilateral trade, indicating that both structural and relational factors significantly contribute to export performance.

Additional evidence from

Eshetu and Mehare (

2020) regarding Ethiopia suggests that increases in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), improvements in road infrastructure, and enhanced domestic savings all contribute positively to export performance. Conversely, foreign direct investment (FDI) and growth in the labour force exert negative effects, underscoring the complex influence of investment and demographic factors on agricultural exports. Parallel findings were documented by

Gbetnkom and Khan (

2020) regarding Cameroon’s exports of cocoa, coffee, and bananas, where infrastructure development and access to credit supported trade activities; however, limited price responsiveness persisted due to constraints within international markets. In Kenya,

Sato (

2020) identified that factors such as economic size, exchange rates, and shared borders with trading partners contribute to bolstering tea exports. Conversely, geographical distance and higher per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in importing countries tended to diminish demand. More recently,

Reaz et al. (

2020) demonstrated that agricultural exports fostered improved firm performance in Malaysia, while

Wani (

2024) and

Wanzala et al. (

2024) emphasised the significance of production capacity, trade liberalisation, and exchange rate volatility in influencing agricultural exports within South Asia and East Africa, respectively.

Studies conducted in South Africa offer additional insights into regional export determinants. For instance,

Idsardi (

2013) identified that gross domestic product (GDP), production capacity, and importer demand are primary drivers of the expansion of high-value agricultural exports.

Mosikari et al. (

2016) similarly affirmed that economic growth within importing Southern African Development Community (SADC) nations has positively impacted South Africa’s agricultural trade.

Potelwa et al. (

2016) demonstrated that GDP and population size in both South Africa and its trading partners exert a positive influence on export performance, while trade agreements such as the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) have strengthened this performance.

Mamashila (

2017) underscored the impact of tariffs, infrastructure, and governance on South Africa’s sugar exports within the context of the Tripartite Free Trade Area. Additionally,

Phaleng (

2020) highlighted the significance of tariffs, production levels, and GDP in shaping fruit exports to West Africa. More contemporary research, including studies by

Seti (

2023) and

Mamashila (

2024a), has explored South Africa’s agricultural trade under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and revealed that structural factors such as infrastructure, labour costs, transportation expenses, and participation in regional blocs remain critical determinants influencing export growth.

Overall, the literature reveals several consistent determinants of agricultural exports across international and South African contexts. Export prices, exchange rates, GDP, population size, production capacity, infrastructure, and trade openness have emerged as recurring factors in the literature. At the same time, studies also pointed to challenges such as policy barriers, limited competitiveness, and exchange rate volatility, which constrain export potential. Notably, however, most existing research has focused on raw agricultural commodities, including fruits, sugar, tea, coffee, and grains. Few studies have examined value-added products, such as wine, whose unique demand drivers, including tourism, consumer preferences, and branding, may influence. This gap is particularly evident in the case of South Africa, where the wine industry has a strong export orientation but remains under-researched in relation to emerging markets in East Africa. The demand for wine in Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius, for example, is closely tied to tourism and evolving consumption trends, which differ from the determinants typically associated with bulk agricultural commodities.

While the literature offers valuable insights into the determinants of agricultural exports, it has mainly concentrated on raw commodities rather than value-added products. As a result, there is a lack of empirical evidence on the export performance of processed agricultural goods such as wine. This gap is especially evident in South Africa, where the wine industry is internationally competitive but under-researched in terms of the factors influencing wine exports to emerging East African markets, such as Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius. These markets are driven more by tourism and lifestyle trends than by traditional drivers of raw agricultural exports. This study addresses this gap by analysing the trends and determinants of South Africa’s wine exports to selected East African countries, employing trend analysis and the gravity model. By focusing on a final, value-added agricultural product, it contributes to the existing body of knowledge and highlights its novelty and originality. Specifically, the study enhances understanding of the drivers and inhibitors of South Africa’s wine export performance in emerging East African markets. It also provides evidence-based insights to mitigate constraining factors and bolster the competitiveness of South African wine in the region.

2.2. Review of Key Factors Affecting Agricultural Exports

The justification for including each explanatory variable in the gravity model, as well as the expected sign of its coefficient, is presented in this section. The rationale is grounded in both theoretical perspectives and empirical evidence from prior international and South African studies. By clearly stating these expectations, the analysis enhances the rigour of the empirical strategy and provides a clearer foundation for interpreting the results. Specifically, the explanatory variables capture supply-side factors (production capacity), macroeconomic conditions (GDP, population, FDI inflows, inflation, and exchange rates), trade-related determinants (import duties, trade openness, and wine prices), and structural determinants (distance), which uniquely shape value-added agricultural exports such as wine. These factors are employed in this study as the key determinants of South Africa’s wine exports to East African markets.

2.2.1. Exporter’s Production Capacity (PC)

Production capacity refers to a country’s ability to produce sufficient quantities of a commodity for both domestic consumption and export, which in agriculture depends on land availability, technology, and infrastructure (

Idsardi, 2013). Empirical studies, including those by

Idsardi (

2013),

Phaleng (

2020), and

Wani (

2024), have demonstrated that higher production levels are strongly associated with export growth, as surplus output can be channelled into international markets. In this study, production capacity is expected to have a positive effect on South Africa’s wine exports to Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius, as greater supply availability enables the industry to meet external demand and remain competitive.

2.2.2. Importers’ Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

GDP represents the total monetary value of all goods and services produced within a country over a specified period, typically measured annually or quarterly (

Mankiw, 2020). Prior studies, such as

Phaleng (

2020),

Mosikari et al. (

2016), and

Wani (

2024), have demonstrated a positive relationship between GDP and agricultural exports. Therefore, in this study, higher GDP in Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius is expected to have a positive influence on wine imports, as greater prosperity expands consumer demand for value-added goods, such as wine.

2.2.3. Importers’ Population (POP)

Population size refers to the total number of people in an importing country and directly affects the size of the consumer base for imports (

Matyas, 1997). Empirical evidence from

Thuong (

2018),

Mamashila (

2017),

Idsardi (

2013),

Potelwa et al. (

2016), and

Wani (

2024) showed that larger populations are positively associated with agricultural imports. Accordingly, in this study, population growth in Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius is expected to positively influence South African wine exports by expanding consumption potential.

2.2.4. Importers’ Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) refers to cross-border investments made to establish lasting economic interest in another country, often linked to infrastructure and market development (

OECD, 2008). Empirical studies, such as those by

Keho (

2020),

Mukhtarov et al. (

2019), and

Karimov (

2020), have confirmed that higher FDI inflows stimulate import demand, particularly in cases where domestic production is limited. In this study, FDI is expected to have a positive impact on South Africa’s wine exports, as increased investment in Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius fosters greater integration with global markets and expands retail and hospitality demand for imported wine.

2.2.5. Import Duties (IDU)

Import duties are taxes imposed on the value of goods entering a country, raising the landed cost of imports and often reducing competitiveness (

SARS, 2021). Previous studies, such as

Mamashila (

2017) and

Phaleng (

2020), have shown that tariffs negatively affect agricultural trade flows by making imports less attractive. Hence, in this study, import duties are expected to exert a negative effect on South African wine exports to Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius, as they increase overall costs for importers.

2.2.6. Importers’ Trade Openness (TO)

Trade openness measures the extent to which a country’s economy allows free flows of goods and services, often expressed as the ratio of total trade (exports + imports) to GDP (

IMF, 2024). Research by

Azhar (

2014) and

Yang et al. (

2022) demonstrated that trade openness positively influences export performance by reducing barriers and creating favourable conditions for foreign goods. Thus, in this study, greater trade openness in Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius is expected to have a positive influence on South African wine exports by facilitating easier market access.

2.2.7. Importers’ Inflation Rate (IR)

The inflation rate measures the pace at which the general level of prices for goods and services rises in an economy, typically expressed as an annual percentage using the Consumer Price Index (

IMF, 2024). Empirical studies, such as those by

Ball (

2005),

Herrera and Baleix (

2010), and

Okpe and Ikpesu (

2021), have indicated that higher inflation in importing countries can stimulate imports if domestic goods become relatively more expensive. Accordingly, in this study, inflation in Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius is expected to have a positive impact on South Africa’s wine exports, as consumers may substitute relatively affordable imported wine for more expensive local products.

2.2.8. Exchange Rate (EX)

The exchange rate reflects the value of one country’s currency relative to another and directly affects the price competitiveness of exports (

IMF, 2009). Evidence from

Idsardi (

2013) and

Phaleng (

2020) suggests that currency depreciation enhances agricultural exports by making them more affordable abroad, although demand for food and agricultural products tends to be relatively inelastic. Therefore, in this study, the exchange rate is expected to have a negative sign, as appreciation of the South African rand would make wine more expensive in Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius, while depreciation would improve competitiveness.

2.2.9. Price of Wine (PW)

The price of wine reflects its average export value and serves as both a determinant of competitiveness and a proxy for quality in consumer perception (

Mosikari et al., 2016). Studies by

Ogede et al. (

2020) and standard demand theory suggest a negative relationship between price and demand, though in premium segments, higher prices may signal superior quality and increase demand. In this study, the expected sign of the wine price is negative overall, but potentially ambiguous due to the hedonic nature of wine as a value-added product.

2.2.10. Distance (DST)

Distance represents the geographical separation between trading partners and is commonly used in gravity models as a proxy for transport costs, logistical efficiency, and market accessibility (

Anderson & van Wincoop, 2003). Empirical studies, such as those by

Tang (

2018) and

Sato (

2020), confirm that greater distance generally reduces trade flows by increasing costs and limiting market integration. In this study, distance is expected to exert a negative effect on South Africa’s wine exports to Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius, as higher transport and distribution costs may reduce competitiveness in more distant markets.

Overall, the reviewed factors demonstrate that agricultural export performance is shaped by supply-side capacity (production capacity), macroeconomic conditions (GDP, population, FDI inflows, inflation, and exchange rates), trade-related determinants (import duties, trade openness, and wine prices), and structural factors such as distance. While the expected signs of these variables are broadly consistent with economic theory and prior empirical evidence, their influence may vary across products and markets. By making these expectations explicit, the study strengthens the empirical strategy and provides a solid foundation for interpreting the determinants of South Africa’s wine exports to East African markets.

4. Results

4.1. Global Overview and Trend Analysis of South Africa’s Wine Exports to Africa

To establish context, an overview of South Africa’s wine exports to key global markets, including Europe, the United States, Canada, and China, is presented first. These markets have historically dominated South Africa’s wine trade, reflecting the industry’s reliance on established, high-value destinations outside the continent of Africa. A trend analysis was then conducted to examine South Africa’s wine export patterns to Africa, providing a comparative perspective. The analysis begins with aggregate export trends for the African continent, followed by a breakdown of regional patterns, and concludes with a focus on the three selected East African markets (Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius). Overall, the trend analysis provides valuable insights into South Africa’s export performance and highlights the role of the selected East African countries as emerging destinations with strong growth potential.

South Africa’s wine exports between 2010 and 2022 demonstrated a general increase in value, despite fluctuations in volumes. Europe, particularly the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Germany, remained the largest markets, with the United Kingdom maintaining a strong role in shaping perceptions of quality and sustaining volume growth through higher-priced bulk exports (

USDA FAS, 2024). The United States also represented a significant market. However, competitiveness has been undermined by the imposition of a 30% tariff in 2022, which placed South African wines at a disadvantage compared to those of EU and Chilean producers (

Financial Times, 2022;

USDA FAS, 2024). Canada emerged as a stable and growing importer, while other African destinations showed promising potential (

USDA FAS, 2024).

Furthermore, China has become an important market due to geopolitical developments, notably trade tensions with Australia (

WESGRO, 2023), which initially created new opportunities for South African exporters. However, recent reports highlight a sustained decline in overall wine demand in China, with the

OIV (

2025) noting a 9.3% drop in consumption in 2024, cautioning against relying on the Chinese market as a stable growth driver for South African wine exports. In contrast, regional markets in East Africa remain underexplored, despite evidence of increasing demand, positioning them as key opportunities for diversification.

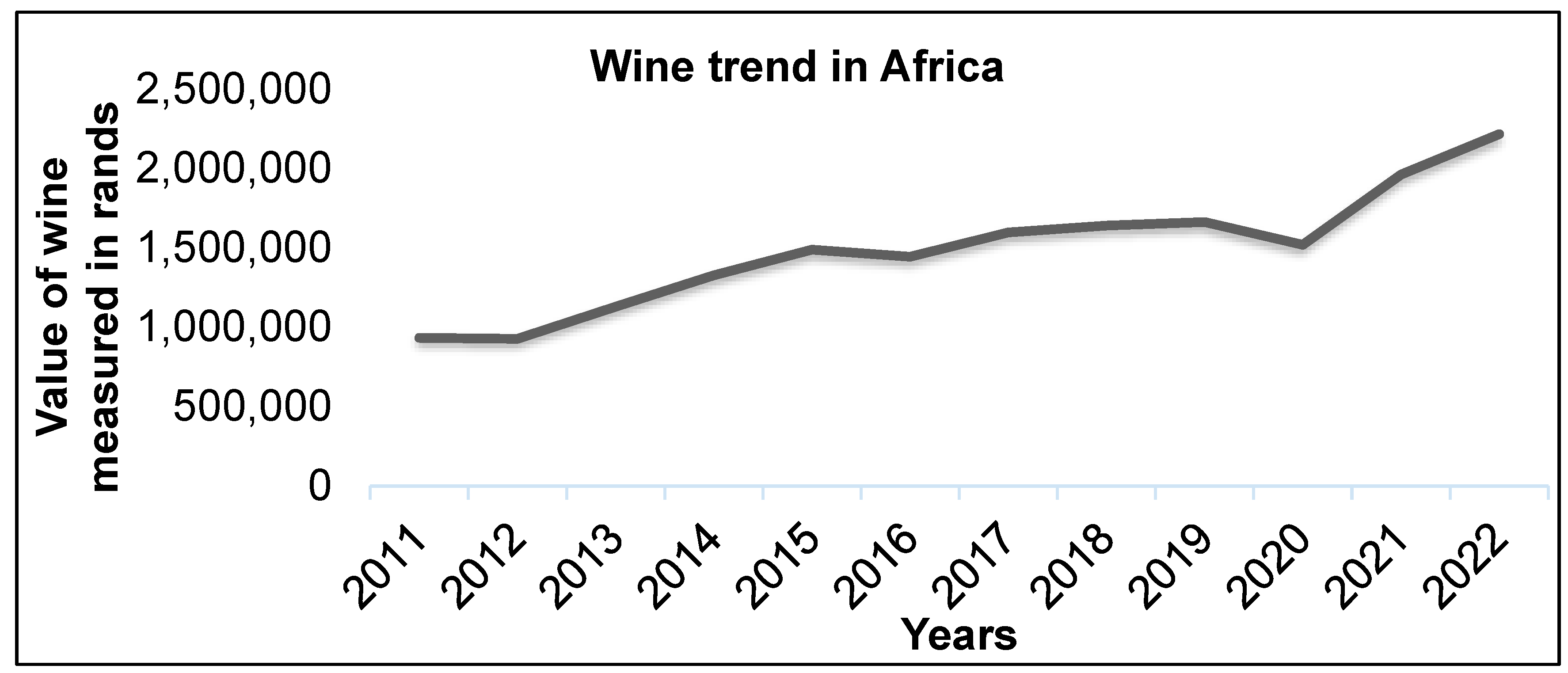

Figure 1 illustrates the overall trend in South Africa’s wine exports to Africa from 2011 to 2022.

South Africa’s wine exports to other African countries generally rose, especially between 2013 and 2015, driven by growing demand and favourable trade conditions. The steep decline in 2020 is attributed to disruptions caused by COVID-19, whereas the decrease between 2017 and 2018 is probably the result of policy or economic changes. The 2021 and 2022 recoveries show that the market was active again after the lockdown.

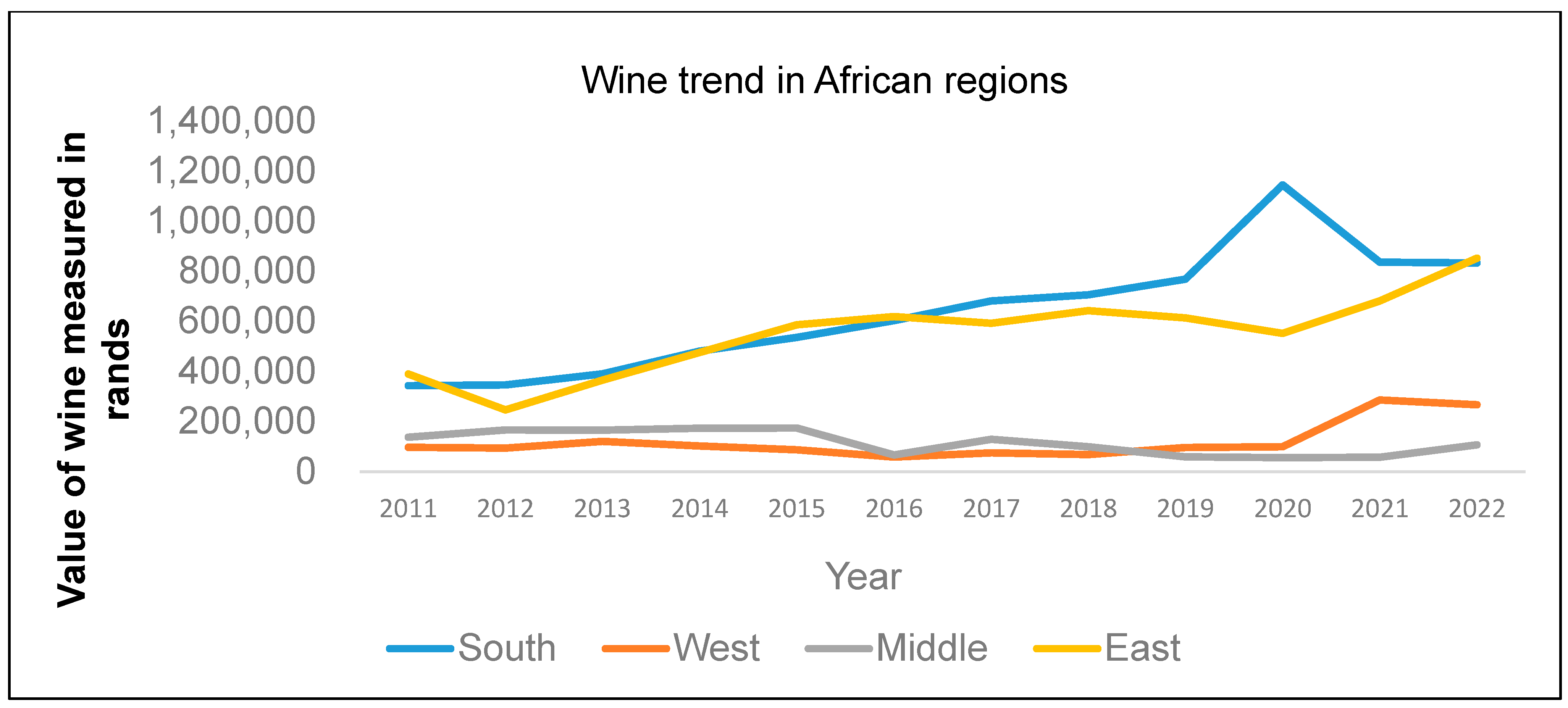

Figure 2 breaks down exports by African region in more detail.

The findings show that Southern and Eastern Africa comprise the largest wine export markets in Africa, with steady growth and occasional peaks. Interestingly, exports to South Africa peaked in 2020, while exports to East Africa performed well in 2015 and 2022. On the other hand, South African wine’s market potential in West and Middle Africa appears to be limited, as evidenced by the region’s consistently low export values over the period. Given the impressive performance of wine exports to East African markets,

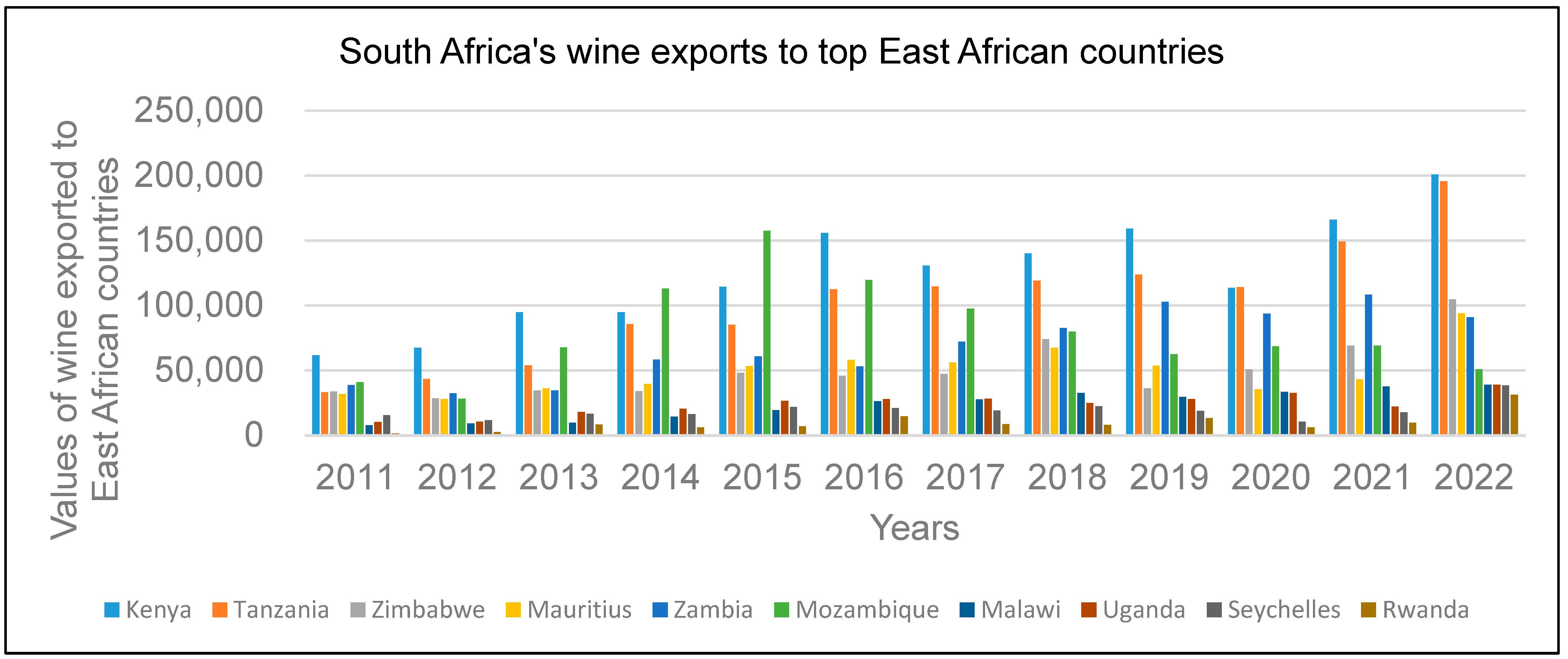

Figure 3 illustrates the patterns in South Africa’s wine exports to the top importing nations, offering justification for prioritising Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius.

Import levels were moderate for Mauritius, whereas Kenya and Tanzania showed strong and stable demand for South African wine, with clear peaks around 2021. On the other hand, countries such as Malawi, Uganda, Seychelles, and Rwanda exhibited limited and irregular import activity, while Zimbabwe and Zambia displayed erratic import trends. Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius were crucial to the recovery of South African wine exports to East Africa after the COVID-19 pandemic, as shown by the significant increase in export volumes in 2021 and 2022.

Overall, the trend analysis confirms that Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius are the most promising East African markets for South African wine exports, justifying their selection for this study. Their steady demand is underpinned by economic growth and expanding tourism sectors, which make a significant contribution to GDP and employment. These factors may have helped drive sustained demand for wine, particularly within luxury hospitality markets. This economic backdrop positions these three countries as key growth markets with substantial opportunities for sustained export growth, while other East African countries remain niche or secondary markets.

4.2. Preliminary Analysis Results

To enhance the robustness of the gravity model, four essential pre-estimation analyses were performed: descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, multicollinearity testing, and unit root testing. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarise the principal characteristics of variables affecting wine exports to Mauritius, Kenya, and Tanzania, as illustrated in

Table 2.

This study quantifies wine exports (EX) as the monetary value of South African wine exported to Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius (

United Nations, 2024), expressed in ZAR millions. The highest average export value was observed for Kenya at ZAR 9.15 million, followed by Tanzania at ZAR 8.68 million, and Mauritius at ZAR 8.29 million.

Wine price (PW) denotes the average selling price of South African wine in bulk, expressed in ZAR. Beyond reflecting market competitiveness and consumer willingness to pay (

Mosikari et al., 2016), price is also widely recognised in both trade and market analysis as a proxy for product quality and brand positioning. This research focused on South African fresh grape wines, specifically bottled still and sparkling varieties (≤2 L, >0.5% alcohol; HS 220421). The mean bulk sale price across three countries was ZAR 345.04, demonstrating relatively stable pricing with minimal variation. Production capacity (PC) signifies the total volume of wine produced in South Africa, measured in billions of litres. It serves as an indicator of South Africa’s export potential as a nation (

SAWIS, 2023). The average production was 1.08 billion litres, indicating a stable supply over time. Import duty (IDU) refers to the tariff imposed on imported wine, expressed as a percentage of import value. It influences the final consumer price and may serve as a trade barrier (

World Trade Organization, 2023). Kenya maintained a fixed 25% import duty, whereas Mauritius and Tanzania applied a 0% rate, consistent with SADC and COMESA protocols (

SARS, 2021). Distance (DST) is defined as the great-circle distance in kilometres between South Africa (exporter) and the capitals of Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius (

Mayer & Zignago, 2011). The longest average distance was observed for Mauritius at 3065 km, followed by Kenya at 2920 km, and Tanzania at 2475 km. The overall mean distance across the three destinations was 2820 km, with a minimum of 2475 km, a maximum of 3065 km, and a standard deviation of 295 km, indicating relatively low variation in geographic proximity among the selected East African markets.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is defined as the net inflows of investment into an importing country, expressed as a percentage of the country’s GDP, reflecting economic integration and investment-driven demand (

OECD, 2008;

World Bank, 2024). Tanzania had the highest average FDI at 2.57%, followed by Kenya at 1.17% and Mauritius at 0.78%. Population (POP) is measured as the total number of residents in each country, expressed in millions. It serves as a proxy for market size and consumption potential (

Matyas, 1997;

Wani, 2024). Tanzania had the highest population at 54.93 million, followed by Kenya at 48.60 million, and Mauritius at 1.26 million. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) represents the total monetary value of all goods and services produced in a country, measured in billions of ZAR. It is a key indicator of purchasing power and demand potential (

Mankiw, 2020). Kenya recorded the highest average GDP at ZAR 1120 billion, followed by Tanzania at ZAR 744.21 billion, and Mauritius at ZAR 157.22 billion.

The inflation rate (IR) is quantified as the annual percentage change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), representing the rate at which prices of goods and services increase (

IMF, 2024). Kenya exhibited the highest average inflation rate at 7.17%, followed by Tanzania at 6.42% and Mauritius at 3.67%. Trade openness (TO) is calculated as the ratio of total trade (exports plus imports) to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), expressed as a percentage, and indicates the degree of economic integration with global markets (

Azhar, 2014;

IMF, 2024). Mauritius demonstrated the highest trade openness at 106.77%, followed by Kenya at 40.43% and Tanzania at 39.37%. The exchange rate (XR) denotes the annual average value of the South African rand relative to the currency of each importing country, expressed in ZAR. It impacts the competitiveness of exports and is essential in international trade pricing (

IMF, 2009). Mauritius recorded the highest exchange rate at 0.32 ZAR, trailed by Kenya at 0.08 ZAR and Tanzania at 0.05 ZAR.

Table 3 displays the correlation matrix, which assesses the strength and direction of relationships between wine exports and key explanatory variables for Mauritius, Kenya, and Tanzania.

Correlation coefficients exceeding 0.7 indicate strong relationships, values between 0.3 and 0.7 suggest moderate correlations, and those below 0.3 are considered weak (

Cohen, 1988;

Evans, 1996). A strong positive correlation was found between wine exports and population size (0.89), highlighting the importance of market size. Moderate positive relationships with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (0.54) and South Africa’s production capacity (0.61) suggest that economic growth and stable supply support export activities. Conversely, trade openness showed a moderate negative correlation (−0.50), possibly due to the presence of protective policies in less open economies. Distance also demonstrated a moderate negative correlation with exports (−0.47), consistent with gravity model expectations that greater geographical separation decreases trade flows. Other variables, including import duty (0.12), foreign direct investment (FDI) (−0.16), inflation (0.24), exchange rate (−0.44), and wine prices (−0.12), exhibited weak associations. Despite these weaker correlations, including all variables remains justified, as they offer additional insights into the complex factors affecting wine exports to selected East African markets.

Table 4 presents the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) results, which were used to assess multicollinearity among the explanatory variables and to support the initial findings from the correlation analysis.

Values under 5 suggest multicollinearity is not an issue, while values between 5 and 10 indicate moderate, but generally acceptable, multicollinearity. Values above 10, however, signal serious multicollinearity that may compromise the stability of the estimates (

Kutner et al., 2005;

Shrestha, 2020). In this study, all VIF values are below the critical threshold of 10, with the highest being 4.06 for the price of wine (PW). Furthermore, all tolerance values exceed the minimum cut-off of 0.1, further confirming that no variable shows problematic collinearity (

Gujarati & Porter, 2009;

Wooldridge, 2013). These results support the reliability and interpretability of the estimated gravity model, confirming that all variables can be included without risking inflated standard errors or distorted parameter estimates.

Table 5 presents the results of the IPS panel unit root test, which was used to assess the stationarity of the dataset.

The IPS test was employed to evaluate whether each panel series contains a unit root, with the null hypothesis indicating non-stationarity. Stationarity guarantees that the time-series properties of the variables are stable over time, thereby minimising the risk of spurious regression results (

Gujarati & Porter, 2009;

Wooldridge, 2013). A

p-value less than 0.05 usually results in the rejection of the null hypothesis, thereby confirming stationarity (

Baltagi, 2008). As demonstrated in

Table 5, the W-statistic of −4.01201 produces a

p-value of 0.000, which is statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating strong evidence against the null hypothesis. This leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis of a unit root, confirming that the panel data series are stationary. Consequently, the stationarity of the data affirms the validity of time-dependent inferences within the gravity model framework.

4.3. Model Test Results

The gravity model was estimated using three econometric specifications suitable for panel data: Pooled Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), Random Effects (RE), and Fixed Effects (FE) models. To select the most appropriate estimation method, two model selection tests were conducted. First, the Redundant Fixed Effects Likelihood Ratio (LR) test was used to determine whether the fixed effects model offers a statistically significant improvement over the pooled OLS model in capturing unobserved heterogeneity across countries. The LR test results are presented in

Table 6.

The results allow a rejection of the null hypothesis in favour of the fixed effects model. This suggests the existence of country-specific effects not adequately captured by the pooled model, thereby confirming that the fixed effects model is more suitable for analysing the determinants of South Africa’s wine exports to the selected East African nations. Subsequently, the Hausman test was performed to determine whether to adopt the fixed or random effects models, by evaluating whether the random effects (RE) model provides consistent estimates, which depends on the presence of correlation between the unobserved effects and the regressors. The findings of the Hausman test are presented in

Table 7.

The results indicate that the test yielded a statistically significant outcome (p < 0.05), thereby leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis. This substantiates the preference for the fixed effects model over the random effects specification. This finding suggests that unobserved country-specific effects are correlated with the explanatory variables and must be controlled through the fixed effects estimator. Collectively, the likelihood ratio and Hausman test results affirm that the fixed effects model is the most suitable specification, as it accounts for unobserved country-specific effects and produces consistent, unbiased estimates for analysing the determinants of South Africa’s wine exports.

4.4. Gravity Model Estimation Results

Following the results of the model selection tests, which confirmed the fixed effects model as the most appropriate specification, the estimated coefficients from the gravity model employing pooled OLS, random effects, and fixed effects methods are displayed in

Table 8. Including all three specifications in

Table 8 facilitates comparison and transparency; the subsequent discussion focuses on interpreting the fixed effects results, as justified by the model selection tests.

Alongside the model selection tests, the overall explanatory power of the estimated gravity models was evaluated using the R-squared, Adjusted R-squared, and Durbin-Watson statistics. As shown in

Table 8, the fixed effects model performs better, with an R-squared value of 0.855 and an adjusted R-squared value of 0.821, indicating a strong explanatory ability. The Durbin-Watson statistic (2.0598) is near the ideal value of 2, indicating no evidence of autocorrelation in the residuals. Based on both the model selection tests and the model fit statistics, the fixed effects model is deemed the most suitable for analysing the determinants of South Africa’s wine exports to the chosen East African countries. Consequently, the following discussion concentrates on the estimated coefficients from the fixed effects model.

The fixed effects model identified several statistically significant determinants of South African wine exports to Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius. Production Capacity (PC) exhibited a positive and statistically significant coefficient of 10.051 at the 5% significance level. This suggests that a 1% increase in production capacity is associated with a 10.05% increase in wine export values, assuming all other factors remain constant. The Inflation Rate (IR) demonstrated a negative and statistically significant coefficient of −22.94 at the 5% significance level, suggesting that a 1% rise in inflation in importing countries is associated with a 22.94% decline in South African wine exports. Population (POP) was found to have a positive and statistically significant impact, with a coefficient of 0.37 at the 5% significance level. This implies that a 1% increase in the population of importing countries is associated with a 0.37% increase in export volumes. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) showed a statistically significant negative relationship with exports, with a coefficient of −8.35 at the 5% level. Hence, a 1% increase in FDI inflows corresponds to an 8.35% decrease in wine exports. Import Duty (IDU) was also significant at the 5% level, with a positive coefficient of 23.96. This suggests that a 1% increase in import duty is associated with a 23.96% increase in wine exports. Finally, the Exchange Rate (XR) displayed a positive and statistically significant coefficient of 30.12 at the 5% level, implying that a 1% depreciation of the South African rand (ZAR) is associated with an approximate 30.12% increase in South African wine exports.

Conversely, Wine Price (PW), Trade Openness (TO), and Importers’ GDP were determined to be statistically insignificant within the fixed effects model. Although these variables were incorporated to consider theoretical expectations and previous empirical findings, their coefficients did not achieve conventional significance levels (p > 0.10). This suggests that, in the context of the three selected East African nations, fluctuations in these factors do not significantly influence changes in wine export values throughout the study period.

Taken together, the results underscore the significance of production capacity, macroeconomic stability, and demographic factors in influencing export performance, while also emphasising the context-dependent nature of trade determinants. The insignificance of GDP and trade openness highlights the complexity of export dynamics, indicating that broader economic size and liberal trade policies alone may not be sufficient to stimulate demand for specific export commodities, such as wine. These insights are instrumental in formulating targeted trade strategies and enhancing export competitiveness within niche markets across the African continent.

4.5. Validation of Fixed Effects Results

While the fixed effects model revealed statistically and economically significant factors influencing wine exports to East African countries, it is essential to validate these findings through robustness and specification checks. Accordingly, the Dumitrescu and Hurlin panel Granger causality test was employed to assess the direction of causality between wine exports and the explanatory variables included in the fixed effects model.

Table 9 presents the test results, which include the direction of causality, W-statistics, Z-bar statistics,

p-values, and indicate whether significant Granger causality exists between exports and each variable.

The test demonstrated unidirectional causality emanating from wine exports towards four variables: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Inflation Rate (IR), Production Capacity (PC), and Price of Wine (PW), all of which are statistically significant at the 5% level. Conversely, no evidence of reverse causality was found, suggesting that these variables do not Granger-cause exports. Furthermore, no causal relationship was observed, regardless of direction, between wine exports and Gross Domestic Product (GDP), population, trade openness, exchange rate, or import duties. These findings suggest that, although the fixed effects model detects correlations, only a limited number of the explanatory variables are causally affected by exports, rather than vice versa. To ensure the robustness of the fixed effects model, four diagnostic tests were conducted, as detailed in

Table 10.

The Normality Test (Jarque–Bera) demonstrated that the residuals conformed to a normal distribution, with a p-value of 0.2374, suggesting that the assumption of normality was not violated. The Serial Correlation Test (Breusch-Godfrey) indicated no significant serial correlation in the residuals, with a p-value of 0.1520, thus confirming the independence over time. The Heteroscedasticity Test (Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey) evidenced constant variance in the error terms, with a p-value of 0.9744, thereby satisfying the homoscedasticity assumption. Lastly, the Functional Form Test (Ramsey RESET) revealed no signs of omitted variable bias or misspecification of the functional form, with a p-value of 0.6699, confirming the correct specification of the model. In summary, the results obtained from both the Granger causality test and the diagnostic assessments underscore the robustness, reliability, and proper specification of the fixed effects model, thus reinforcing confidence in the empirical findings concerning the determinants of South Africa’s wine exports to East African nations.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the determinants of South Africa’s wine exports to Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius using trend analysis (2011–2022) and an augmented gravity model. Guided by the literature, it was hypothesised that GDP, population, FDI, trade openness, and production capacity would promote exports, while import duties, inflation, exchange rates, and wine prices would constrain them. The results partially confirmed these expectations. Specifically, production capacity, population, exchange rates, import duties, inflation, and distance emerged as significant determinants, while GDP, FDI, trade openness, and wine prices showed no statistical significance. The insignificance of these variables suggests that broader economic growth and investment have not translated into higher wine demand, likely due to consumer preferences, limited market penetration, competing beverages, and niche consumption patterns where cultural and social factors outweigh price sensitivity.

The significant results imply that the exportation of South African wine to Kenya, Tanzania, and Mauritius is primarily shaped by supply-side capacity (production capacity), macroeconomic stability (inflation and exchange rates), and trade conditions (import duties), with population size further reinforcing demand in importing countries. Together, these determinants highlight the interplay of production, economic, and policy factors in influencing South Africa’s wine exports to East Africa.

For producers and industry stakeholders, the findings suggest that scaling up production to meet external demand, coupled with investment in quality enhancement and brand differentiation, will be critical in sustaining wine export growth. Maintaining stable but competitive pricing strategies may also help absorb the negative effects of inflation in importing countries, particularly in tourism-driven segments of the market. For policymakers and trade regulators, the results highlight the importance of targeted interventions, such as negotiating favourable tariff regimes, ensuring exchange rate stability, and developing risk-mitigation tools to cushion inflationary shocks. Furthermore, harmonising non-tariff measures and facilitating cross-border logistics could address product-specific trade barriers that persist even in liberalised trade environments.

By clarifying both the drivers and constraints of wine export performance, this study makes a novel contribution to the literature on value-added agricultural trade in emerging East African markets. Unlike raw commodities, wine exports are often associated with lifestyle and tourism dynamics, as highlighted in the literature, which suggests that they may require a comprehensive approach from both exporters and regulators.

Ultimately, while the study offers new insights, it is not without its limitations. The analysis was confined to three East African countries and a relatively short period (2010–2022). Future research should broaden the scope to include additional emerging African markets such as Uganda, Rwanda, and Ethiopia, which are experiencing rapid growth in tourism and urban middle-class consumption, and cover other product categories within the wine industry beyond bottled still and sparkling grape wines (HS 220421), such as bulk and fortified wines, to capture a fuller picture of export dynamics. It should also extend the timeframe beyond 2022 and adopt a longer historical perspective to capture evolving trade patterns and structural shocks while also integrating data from the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV) to broaden coverage and incorporate the most recent years, thereby enhancing robustness and timeliness. Moreover, tourism plays a role in stimulating wine exports, both directly through tourist consumption and indirectly by influencing demand in tourists’ home countries. Still, its omission here reflects concerns with endogeneity and scope, making it a valuable avenue for future research. Similarly, cultural and religious factors, such as the proportion of the Muslim population, can significantly influence alcohol consumption patterns and merit consideration in extended gravity model applications, thereby enriching the understanding of wine trade dynamics in diverse markets. Additionally, unit values offer valuable insights into export characteristics and market positioning; however, since this study focused on aggregate trade values and volumes, future research could analyse unit value dynamics to better capture product differences and consumer preferences across markets.