1. Introduction

Globally, pressure is witnessed on food systems, which are deteriorating due to climate change, military conflicts, migration phenomena, and economic crises. Addressing this problem is an urgent international issue relevant to the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) member states. According to

FAO and ECO-RCCFS (

2025), in ECO countries, approximately 59 million people still suffer from undernourishment, which means that 13% of the population faces the risk of hunger.

The rationale of this research starts from the premise that the topics of food trade and security in the ECO region are underexplored in the academic literature, especially considering that the member countries are strategically located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, giving them the unique opportunity to serve as trade hubs. This paper intends to fill the above-mentioned gap in the literature by emphasizing the fact that food trade plays a crucial role in addressing food security challenges and providing valuable insights, empirical evidence, and recommendations for decision-makers, traders, and stakeholders.

A comprehensive understanding of ECO’s foundation and objectives is indispensable for situating this study within its appropriate geopolitical and institutional context. The ECO region shelters more than 460 million inhabitants and spans over 8 million square kilometers, connecting Asia to Europe and Eurasia to the Arab World. Composed of some Caucasus, South, West, and Central Asian countries, ECO is one of the oldest intergovernmental organizations (

https://eco.int/history/, accessed on 3 June 2025).

Pomfret (

1997) presents comprehensively the origins of ECO and its evolution. ECO was established in 1964 by Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey under the name of Regional Cooperation for Development (RCD), aiming to promote economic, technical, and cultural cooperation among the member states. In 1985, RCD was renamed Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), expanding its scope and trying to enhance regional cooperation. After the end of the Cold War, in 1992, ECO received seven new members: Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. In this way, the total membership amounted to ten, the countries being united by common economic, historical, and cultural ties. The organization’s objectives, stipulated in its Charter, the Treaty of Izmir, include the promotion of conditions for sustained economic growth in the region (

Turner, 2010). They also include promotion of regional trade, transportation, energy, and economic integration. ECO supported ECOTA (ECO Trade Agreement—aiming to promote regional trade by reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers and fostering economic regional integration) and cross-border connectivity between the member countries by railway and road networks. This regional organization has contributed, over the years, to the development of projects focusing on sustainability, energy security, and intra-regional trade. It has also tried to solve the challenges confronted by the region, fighting to reduce poverty and to build infrastructure.

It can be seen that ECO has indeed clear objectives and a structured setup, but many agreements lack enforcement due to bureaucratic inefficiencies (as shown in different scientific publications, such as

Ali & Mujahid, 2015; or

Pomfret, 1997). In addition, some geopolitical tensions (for example, Iran confronted with Western nations’ sanctions and Pakistan–India tense relations) restrict cooperation and efforts of integration. Other challenges are represented by the economic disparities between the member countries and the limited international influence (unlike the EU or other regional organizations, ECO has a much weaker global presence).

ECO is an organization characterized by the diversity of political systems, from democracies (e.g., Turkey and Pakistan) to authoritarian regimes (e.g., Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan). These differences can lead to various approaches to economic policy priorities. As shown above, differences also exist in terms of economic development, with some countries being rich in resources, such as Iran and Kazakhstan, and others being poorer, such as Afghanistan and Kyrgyzstan. Also, some member states are facing internal conflicts, such as Afghanistan or Pakistan. There are disputes and rivalries even between member states, related to borders or possession of resources. Finally, the region is subject to geopolitical influences from global powers such as China, Russia, and the USA. As a result, ECO faces challenges that economic and cultural cooperation can mitigate or overcome.

The food trade and food security were chosen for discussion because the agricultural sector plays a significant role in ECO countries’ economies, especially in less industrialized members like Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Afghanistan. Even in more industrialized states like Turkey, agriculture still holds an important role, given that agricultural land accounts for half of the national territory, and nearly one-quarter of the population is employed in the agricultural sector (

International Trade Administration, 2024). The economic contribution of the agricultural sector is that of providing livelihoods for a great part of the population, particularly in rural areas, thus supporting food security in these countries. Agricultural products also form a major part of exports for ECO member states. According to the

Economic Cooperation Organization (

2023), most ECO members depend significantly on the agri-food sector as a key driver of economic growth, trade, and investment.

The objective of this study is to analyze the food trade and food availability (as a component of food security) within the ECO and to examine the moderating effect of imports on the relationship between food export and food availability across member states.

The research methodology includes both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The qualitative methods are represented by historical and document analysis to understand ECO’s evolution and the development of its agri-food sector. The quantitative approach is a regression model based on two research hypotheses and the estimation of moderating effects, using food availability, export of food, and import of food as indicators.

To reach the study objectives, the paper is structured as follows: the subsequent section provides an overview of the existing literature, followed by describing the importance of the ECO agri-food sector; the analysis continues with a regression model for testing the effect of import of food on the relation between export of food and food availability; the last section discusses the results obtained and presents the concluding remarks and some policy recommendations.

2. Literature Overview

The works exploring ECO’s food trade and security are limited, although these topics have great potential for interest for researchers and policymakers.

At the same time, the literature on ECO’s food trade and security remains relatively fragmented, with contributions approaching the topic from different but complementary angles. One recurrent limitation across these works is that while they emphasize the vulnerabilities of ECO countries, they often stop short of providing integrated frameworks that account for both intra-regional dynamics and global trade dependencies.

Turner (

2010) provides a broad institutional overview of ECO’s objectives, stressing the organization’s ambition to promote economic integration across diverse sectors. However, this early work remains largely aspirational and descriptive, focusing more on ECO’s official rhetoric than on its actual performance. In contrast, the more recent studies by

FAO and ECO-RCCFS (

2019,

2022) move beyond institutional ambitions and directly assess food security outcomes, particularly in light of crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. These later works emphasize the systemic risks tied to cereal import dependency, malnutrition, and climate change, underscoring the region’s acute vulnerabilities. The comparative strength of FAO’s analyses lies in their empirical grounding and policy-oriented recommendations, though they remain primarily diagnostic rather than predictive, offering limited insight into the political feasibility of the proposed measures.

A notable tension emerges between the findings of

FAO and ECO-RCCFS (

2025) and

Mueez (

2024). Whereas FAO highlights the external dimensions of vulnerability (global commodity dependence, import reliance, climate risks), Mueez underscores the region’s internal structural weaknesses, such as weak institutions, inadequate trade policies, and limited intra-regional cooperation. The juxtaposition of these perspectives suggests that ECO’s food security challenges are not only a matter of external shocks but also of insufficient regional integration, with intra-regional trade accounting for only 8% of total trade. Taken together, these findings highlight a dual exposure: ECO countries are both externally dependent on volatile international markets and internally constrained by fragmented economic cooperation.

When comparing ECO-specific analyses to broader, cross-country perspectives, further insights emerge.

FAO (

2021,

2024) situates ECO within a global policy framework, emphasizing trade openness and diversification of trade partners as mechanisms to enhance agri-food resilience. This global perspective strengthens the argument that ECO’s current reliance on a narrow set of commodities and partners leaves it highly vulnerable. Yet, ECO-specific literature often fails to connect these broader lessons to the region’s unique geopolitical context, where political instability and sanctions further complicate trade diversification.

Bozsik et al. (

2022) provide an instructive comparative case by analyzing Colombia and Kyrgyzstan. Their findings underscore the importance of aligning food security with monetary and trade policies—a lesson that is only partly acknowledged in ECO-focused literature. By bringing in a non-ECO comparator (Colombia), the study highlights that ECO’s challenges are not entirely unique; rather, they reflect broader structural issues in developing economies with similar dependency patterns. Still, unlike the FAO’s global recommendations, Bozsik et al. link food security more directly to national macroeconomic policy, thereby pointing to a critical research gap: how ECO states’ fiscal and monetary choices constrain or enable their food security strategies.

Overall, the literature points to three converging but insufficiently integrated strands of analysis: (1) institutional aspirations versus realities (Turner, Mueez); (2) food security vulnerabilities and policy recommendations (FAO/ECO-RCCFS, FAO global studies); and (3) comparative economic insights from similar developing contexts (Bozsik et al.). What is missing is a holistic approach that simultaneously considers internal integration, external trade dependencies, and domestic economic governance. This gap underscores the need for further empirical research that not only documents vulnerabilities but also critically examines the political economy of ECO’s integration and its implications for long-term food resilience.

3. Development of the Agri-Food Sector in ECO Member States

The agri-food sector represents a vital part of the economies of ECO countries, with considerable potential for growth and development.

Agriculture remains a critical component of GDP in many ECO countries. It is central for food security, rural employment, and export revenue.

Table 1 below presents the GDP share of agriculture in 2023.

It is observed that agriculture indeed holds a significant share in total production, the countries with the highest percentages being Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

At present, intra-ECO trade in food products is underutilized. However, according to the ECO Secretariat, ECO Statistical Report 2021, trade facilitation via agricultural products exchange has proven effective. The data in the report above show that the increased meat production has contributed to the trade among ECO member countries by relative and absolute measures. Trade in meat and meat products generates approximately USD 1.5 billion in business among the ECO countries. But, despite ECOTA (ECO Trade Agreement), in force since 2008, agri-food trade remains under 10% of total regional trade, due to barriers such as non-tariff restrictions, complex customs procedures, lack of infrastructure, high transport costs, and varying levels of agricultural development (

FAO & ECO-RCCFS, 2022).

One of the most important documents of the organization, ECO Vision 2025 and Implementation Framework (

Economic Cooperation Organization, 2017), states that agriculture and industry are the key sectors that can boost economic growth. This document highlights the struggle to eradicate hunger and poverty, which must be waged especially in rural areas, where half of the population of ECO countries lives. It is, therefore, evident that there is a concern for eradicating hunger through a combination of pro-poor investment in sustainable agriculture, rural development, and social protection measures aimed at lifting people out of poverty and chronic undernutrition. The goal is to meet regional food demand by increasing agricultural productivity, implementing agricultural policy reforms, making optimal use of natural resources (especially water), and stimulating international trade within the ECO region. The same document states that the scope of ECOTA will be enhanced from preferential trade to a Free Trade Agreement.

However, a critical analysis of the feasibility of implementing ECO Vision 2025 in the current context is necessary. In principle, we consider that the measures related to the agri-food sector can be implemented, but their success depends on several key factors:

Political will. The genuine commitment of ECO member governments to the proposed vision is essential. Without strong political support and in the absence of supranational institutions (such as those within the European Union), the proposed reforms for the agri-food sector risk remaining merely declarative.

Institutional capacity. ECO member states exhibit varying levels of administrative development, including administrative legacies (e.g., Soviet-style bureaucracies in Central Asia vs. different traditions in Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan). The effective implementation of measures such as pro-poor investment or agricultural policy reforms requires competent and transparent institutions.

Financial and technical resources. Implementing reforms related to agriculture and eradicating hunger and poverty requires public, private, or external funding, as well as technical expertise. However, some ECO member states face significant budgetary constraints (see

Table 2, which presents the highest budget deficits in ECO member states).

Regional cooperation. The success of ECO Vision 2025 depends on close collaboration between member states in areas such as trade policies, cross-border infrastructure, and the exchange of best practices.

At present, several factors can be identified that hinder the achievement of the proposed objectives, such as political instability in the region and ongoing conflicts, significant disparities in economic development, lack of infrastructure, climate crises, and prolonged droughts. The latter, in particular, may directly impact agriculture, food security, and sustainable rural development. The regional cooperation is hindered by the fact that ECO members intend mainly to develop their own countries instead of feeling integrated into a greater organization.

4. Regression Model for Testing the Effect of the Import of Food on the Relationship Between the Export of Food and Food Availability

According to the

Economic Cooperation Organization (

2023), ECO is committed to Sustainable Goal 2, Zero Hunger, the accomplishment of which will lead to greater food security, health, and welfare. The same document asserts that ECO food export is much below its potential. At the same time, according to the ECO Secretariat, ECO Statistical Report 2021, ECO’s total export of food (USD billion) equals 29,779 (The biggest exporters of food being Turkey (16,672), Iran (4615), and Pakistan (4008)), and ECO’s total import of food (USD billion) equals 3867 (The biggest importers of food being Turkmenistan (1829), Turkey (619), and Iran (329)), so the region has a positive current account balance for food products, with exports far exceeding imports. This situation raises questions regarding the availability of food (as a component of food security) domestically. This is why it would be interesting to investigate the effect of food imports on the relationship between the export of food and food availability in the ECO region, using a regression model.

H0: There is no moderating effect of the Import of food on the relationship between the Export of food and Food availability.

H1: There is a moderating effect of the Import of food on the relationship between the Export of food and Food availability.

4.1. Regression Function Design

To express the statistical relationship between the Availability of food (as a dimension of food security) and the Export of food, the authors applied a regression analysis. One moderator indicator is included in the model, and refers to the Import of food (Moderator 1). Also, the model includes one dependent variable (Export of food) and one independent variable (Food availability). The model can be written with the function:

For the design of the regression function, the following indicators were used:

Food availability (abbreviated FAv) (X(VI))—According to

FAO and ECO-RCCFS (

2019), a food (in)secure situation can be characterized by multiple factors, including domestic production, trade, aid, market structure/conduct, income distribution, public/individual health, and the ability of a society/community to cope with shocks. Based on this information, a series of indicators (supported by the above-mentioned report as descriptors of a country’s food security) has been identified. Consequently, the FAv indicator was defined as the average of: average dietary energy supply adequacy; share of dietary energy supply derived from cereals, roots, and tubers; average protein supply; average supply of protein of animal origin. The rationale for calculating this indicator as an average of the aforementioned variables is grounded in the guidance provided by

FAO and ECO-RCCFS (

2019), in the section Indicators to measure and monitor food security.

Export of food (abbreviated EF) (Y(VD))—the data used were taken from the ECO Statistical Report 2021, which allowed easy access to regional statistical data. This information supports ECO’s regional initiatives (

ECO Secretariat, 2021). The indicator is expressed in USD billion.

Import of food (abbreviated IF) (W(MO))—the data are taken from ECO Statistical Report 2021 (

ECO Secretariat, 2021). The indicator is expressed in USD million.

All indicators were considered and included in the model for 10 countries: Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Cross-sectional data for the year 2018 were retrieved from the above-mentioned reports, as more recent data are not available.

4.2. Data Analysis Technique Used

The data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. A moderation analysis is performed. To do this, moderating effects are estimated. To verify the proposed hypotheses, the authors chose to use Model 1 from the PROCESS macro in SPSS software (

Hayes, 2022). The PROCESS SPSS Macro (

Hayes, 2017) was used. The PROCESS macro approach was chosen over SEM analysis because it represents a more recent and modern method of data analysis, which provides a graphical depiction of moderated relationships. Moreover, this approach supports the assessment of the validity of the proposed model and indicates whether the constructed model can be accepted or rejected.

The following indicators were calculated: β, Se, R2, F, p-value, t-test, and the effects of the coefficients. The results, based on the obtained values (β = −4.0539; t = −6.1070; p = 0.0009), highlighted a negative and statistically significant impact of IF on the relationship between EF and FAv, while the regression function indicates that the overall regression is statistically significant.

4.3. Influence of Imports on the Relationship Between Exports and Food Availability

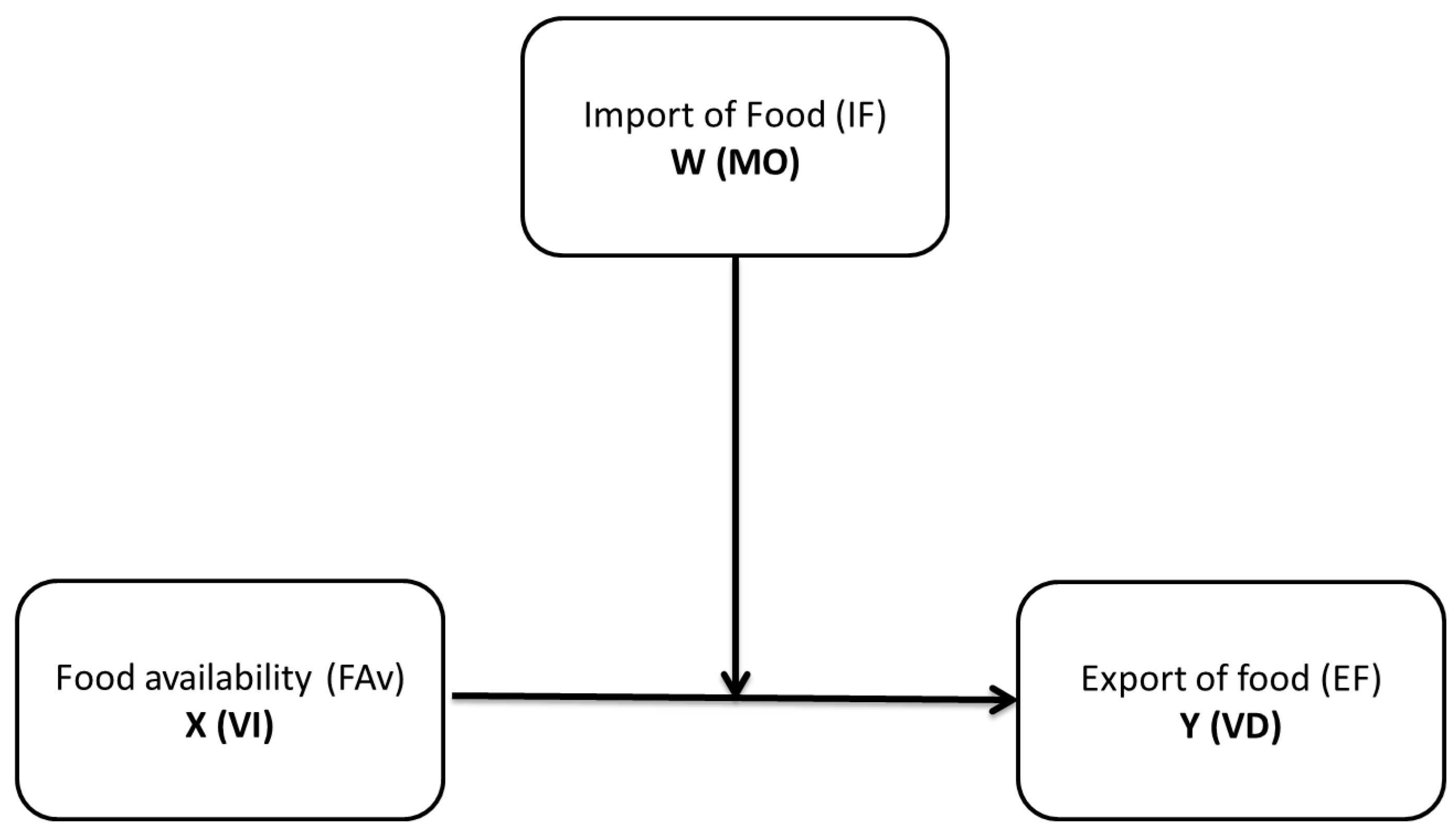

The proposed model comprises the variables presented in

Figure 1 below.

The model summary reflects that the value of equals 0.8770, which means that 87% of the Import of food variation is explained by Export of food, Food availability, and their interaction; the interaction term is significant (because F (3,6) = 14.25 and p = 0.0039).

Because

p = 0.0009 and the confidence interval does not encompass the zero value, it can be concluded that the interaction effect is statistically significant, which indicates that the relation between Export of food (EF) and Food availability (FAv) is moderated by Import of food. The moderation effect is then presented in

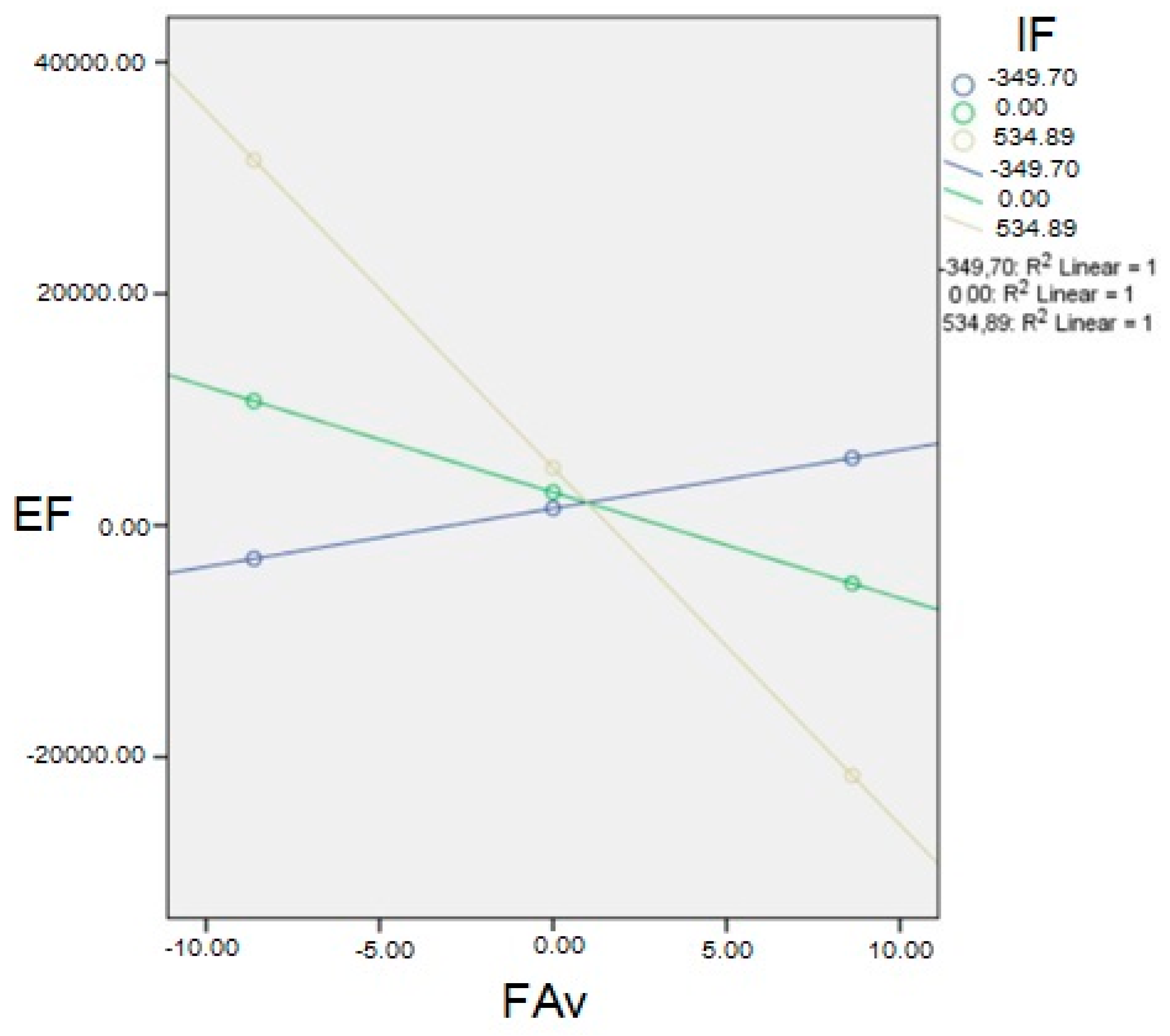

Figure 2.

As can be seen from

Figure 2, the Import of food (IF) reinforces the negative relationship between the Export of food (EF) and Food availability (FAv).

Table 3 shows the values of the standard error (with values between 0.66 and 692.316). At the same time, it is observed that the estimators are significantly different from zero because

p-value < 0.05 (constant

p = 0.0061; Food availability

p = 0.0008; Import of food

p = 0.0351; interaction

p = 0.0009). The value recorded by the confidence intervals of the coefficients confirms the same finding because the superior and inferior limits do not pass through zero.

But how does the import of food moderate the relationship? As

Table 3 shows, the relationship is moderated negatively (β = −4.0539). In other words, the higher the value of the Import of food (IF), the weaker the relationship between Food availability (FAv) and the Export of food (EF). A standard error value ranging from −1269.40 to 4559.50 can be observed. At the same time, the estimators are significantly different from zero because each records a

p-value lower than 0.05—the significance threshold allowed for the estimators’ confidence intervals, therefore, implicitly at a probability of 95%.

Along with the presented interaction, there is also a significant modification of

, which takes the value of 0.7646, according to the data of

Table 4, showing that the interaction has a significant impact on the endogenous variable. In conclusion, the effect is significant.

To establish if the effect is different depending on the level reached by the analyzed region (including the 10 countries), as regards the Import of food, the authors resorted to a bootstrapping procedure by quantifying the effect of low level (−1 SD), the effect of the mean level, and the effect of high level (+1 SD).

Table 5 presents the effects of the predictor coefficient (Export of food) on the moderator values (Import of food).

In

Table 5, the effect is observed for the three levels of Import of food (IF) (low, medium, high). As can be seen, at a low level of the moderator (Import of food), the size of the effect of the predictor (the association between Export of food (EF) and Food availability (FAv)) is high (strong). The effect size decreases at the mean level. At a high level of Import of food (IF), an even lower effect is observed, which has a negative impact. All these effects are statistically significant, both at low and medium levels, and high levels, due to the

p-value, and furthermore, because the confidence interval does not encompass zero. The statement is also supported by the decrease in the coefficient from the value of 504.08 (low level of IF) to −3081.95 (high level of IF).

The study evaluated the role of the moderator Import of food (IF) on the relationship between Export of food (EF) and Food availability (FAv). The results highlighted a negative and statistically significant impact of IF on the relationship between EF and FAv (β = −4.0539; t = −6.1070;

p = 0.0009—see

Table 3).

The empirical findings support the validity of the alternative hypothesis (H1), highlighting the existence of a statistically significant moderating effect of Import of food (IF) on the relationship between Export of food (EF) and Food availability (FAv). The results suggest that as the volume of imports increases, the negative relationship between exports and food availability diminishes. This outcome underlines the critical role of imports in ensuring food availability (as a component of food security) in the ECO member countries.

5. Discussion, Conclusions, and Policy Recommendations

ECO has the potential to become a powerful economic organization, connecting the Middle East, Central, and South Asia. The critical analysis of the feasibility of implementing measures related to the agri-food sector revealed that it depends on some key factors: political will, institutional capacity, financial and technical resources, and regional cooperation; several factors were identified that can hinder ECO’s proposed objectives, such as political instability of the region, ongoing conflicts, disparities in economic development, and lack of infrastructure.

As

OECD/FAO/UNCDF (

2016) highlights, tackling food security in the ECO region calls for innovative policy approaches, illustrating that geography matters; different territories need different policy responses to account for their specific challenges.

This study demonstrates the existence of a relationship between the Export of food and Food availability, moderated by the Import of food of ECO countries. In this sense, the interaction effect is statistically significant, as shown in the regression analysis. More than that, the regression model developed by the authors shows that the Import of food reinforces the negative relationship between the Export of food and Food availability.

ECO region is a net exporter of food, as illustrated by

ECO Statistical Appendix (

2020); the regression model confirmed that there is a moderating effect of the Import of food on the relationship between Export of food and Food availability. Food imports can indeed influence this relationship by balancing supply (by supplementing shortages or assuring diverse food sources), stabilizing prices (by preventing price increases and mitigating market fluctuations), and increasing food security. The results of our regression model have important policy implications: governments can use trade policies to equilibrate exports and imports in a way that assures food security. For example, a country could reduce import tariffs to promote imports when food availability is reduced because of big exports, or could offer import subsidies for essential food products, making them affordable for the population, especially when food exports are high.

Food availability in the ECO region is a mixed picture, with some countries having a secure food supply and others confronting scarce sources of food. As many ECO countries rely on food imports to satisfy their domestic needs, facing water scarcity, climate change, or political instability, their governments should indeed stimulate food imports or require international assistance and food aid. However, imports of food in the ECO region depend on each state’s trade policies, which are characterized by various tariffs, quotas, or even non-tariff barriers. The tariffs on food imports are different across the ECO region. For example, Turkey and Pakistan have a trade arrangement with defined tariffs on food imports, while others practice protective tariffs to shield the local producers, according to the

FAO and ECO-RCCFS (

2019). Imports of food could also be restricted by non-tariff barriers, considering that countries may impose phytosanitary requirements on food imports to respond to some safety and health standards. All these factors could reduce trade and affect the supply of food. Following the example of the European Union, a single ECO market would be a solution for the above-mentioned problems.

Table 6 below summarizes the main trade and food security policy recommendations. The proposed trade policies derive from the results of the quantitative analysis of this study, indicating the importance of imports and consequently of the need to eliminate the existing trade barriers; and the food security measures are more related to the qualitative and historical analysis of the ECO development and integration process.

Being determined by a complex interaction of economic, institutional, environmental, geopolitical, and security factors, trade policies should be improved in the coming years in the ECO region. A constructive dialogue among ECO member countries is also needed to develop a strong regional program for assuring food security.

ECO should design more flexible structures for a deeper integration in the food trade area, arriving in the end at a customs union, which allows the free circulation of agricultural products.

Our study presents some limitations, mainly because recent data are difficult to find in the ECO statistical reports. In addition, the regression result must be interpreted with caution: while food imports can supplement domestic supply, they can also negatively influence local agriculture by creating a competition that local farmers cannot resist; this evolution can reduce domestic food production and exports and ultimately affect food availability. Therefore, we must take into account the fact that the relationship between food imports, exports, and food availability is complex and strongly dependent on both international market conditions and specific national or regional policies. At the same time, food availability is only one component of food security; the availability alone does not guarantee food security. Even if food is available in markets, people may still be food insecure if they cannot afford it, or if conflicts or disasters disrupt access. This creates the potential for future research by taking into account a wider range of indicators reflecting the phenomenon of food security.