1. Introduction

Consumption is a fundamental pillar of global economic growth, consistently accounting for over 60% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in most nations, particularly in developed economies like the United States, where it constitutes approximately 70% of GDP. Understanding the dynamics of consumption is therefore crucial for economic stability and prosperity. Since the mid-20th century, economists have sought to model aggregate consumption, with early European scholars beginning to consciously examine the influence of demographic structures, such as age and gender (

Blinder, 1975). This focus has intensified with the global acceleration of population aging. Developed Western nations entered aging societies years ago, and China is now experiencing a particularly rapid increase in its elderly population. In this background, China’s 14th Five-Year Plan outlines a national strategy to actively address population aging. The key to addressing this challenge is to uncover the unique consumption preferences of this demographic, as understanding their specific preferences and behaviors is essential for developing effective strategies to boost their spending.

Traditional economic theories, such as

Modigliani and Ando’s (

1963) life-cycle hypothesis, posit that consumption depends on an individual’s total lifetime resources, including existing wealth and the present value of future expected income. This framework suggests individuals actively plan to smooth consumption over their lives to maximize utility, driven by a preference for stable spending levels. Consequently, household consumption patterns often exhibit a “hump-shaped” curve over the life cycle, reflecting varying consumption and saving decisions at different stages (

Carroll, 1994).

Existing research has identified intergenerational differences in consumption preferences.

Ji and Li (

2025) used data from the China Household Finance Survey revealed that the degree of population aging exerts a significantly positive effect on household tourism expenditure. Additionally, some researchers have used Chinese data to find that a higher proportion of elderly people helps promote developmental consumption (

Fan et al., 2024). In developed countries, older individuals tend to consume more than younger ones, with a notable trend of wealth flowing from younger to older generations (

Lee & Mason, 2010). This accumulated wealth provides a foundation for higher consumption among the elderly. Moreover, older individuals often exhibit distinct preferences in specific sectors. For instance, differences in tourism consumption preferences exist between older and younger adults (

Szmigin & Carrigan, 2001), with younger consumers being more sensitive to discounts (

Moschis & Ünal, 2008). Interestingly, older consumers may also show a greater preference for newly launched products (

Szmigin & Carrigan, 2000). While these studies indicate that household consumption changes over the life cycle and consumption preferences show intergenerational variations, there remains a notable gap in the academic literature regarding the time-varying characteristics of individual consumption preferences at a micro-level.

This paper aims to bridge this gap by exploring the specific impact of age on consumer preferences within the context of China’s rapidly aging population. We utilize a novel approach to measure consumption preferences across various categories and empirically analyze their life-cycle dynamics, including how these dynamics are moderated by socioeconomic factors and differ across regions and specific consumption types. Our principal conclusion challenges the conventional notion of low consumption among the elderly, demonstrating that older individuals’ consumption preferences actually increase with age, suggesting a potentially positive impact of population aging on overall consumption.

2. Data and Methodology

To investigate the time-varying characteristics of Chinese consumer preferences, this study utilizes pooled panel data from the 2015, 2017, and 2019 waves of the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) for regression analysis. To mitigate the influence of extreme values, the data were winsorized at the 1% threshold. After filtering out household heads younger than 20 years old (using the legal marriage age as a screening criterion), a panel dataset comprising 112,000 individual observations was constructed.

To facilitate a more granular analysis of consumer preferences across different consumption categories, we classify consumption into two broad categories: subsistence consumption and developmental consumption. These two main categories will be further disaggregated into eight specific sub-categories during subsequent heterogeneity analyses. The descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in

Table 1.

This study quantifies consumer preferences using the Target Group Index (TGI), a metric commonly employed to describe user profiles, based on the Empirical Revealed Preference (ERP) theory. Specifically, ERP theory posits that consumers’ actual choices reveal their consumption preferences, asserting that purchasing behavior in response to different products discloses underlying preferences (

Crawford & De Rock, 2014). Building on this theory, we first calculated the total expenditure for each consumption category across all provinces annually. Subsequently, each province was weighted by its GDP for that year. These weights were then used to compute the national average expenditure for each consumption category. This national average serves as our benchmark for measuring consumer preference: if a consumer’s cumulative expenditure on a given category within a year exceeds this weighted national average, that consumer is deemed to prefer that particular consumption category.

The TGI is effective in revealing the consumption characteristics of a specific target group (

AlBedah et al., 2011). In this paper, we construct the TGI with different communities as the target groups to explore the characteristics of communities that prefer various consumption categories nationwide. The specific calculation is presented in Equation (1):

The Target Group Index (TGI) is calculated by dividing the proportion of people within a specific community who prefer a certain consumption category by the proportion of people nationwide who prefer that same category, then multiplying the result by 100. If the calculated TGI is greater than 100, it indicates a strong preference for that consumption category within the community; conversely, a TGI of 100 or less suggests no strong preference. A higher TGI value signifies a greater preference for that consumption category among consumers in that group.

In our subsequent empirical analysis, we categorize consumers’ TGI into Subsistence TGI and Developmental TGI. The Subsistence TGI represents the ratio of the proportion of individuals within the target group who prefer subsistence consumption to the proportion of individuals in the overall population who prefer subsistence consumption. Similarly, the Developmental TGI represents the ratio of the proportion of individuals within the target group who prefer developmental consumption to the proportion of individuals in the overall population who prefer developmental consumption. The specific formulas are provided below:

Consistent with existing literature on preference measurement, we hypothesize a nonlinear relationship between age and consumption preferences (

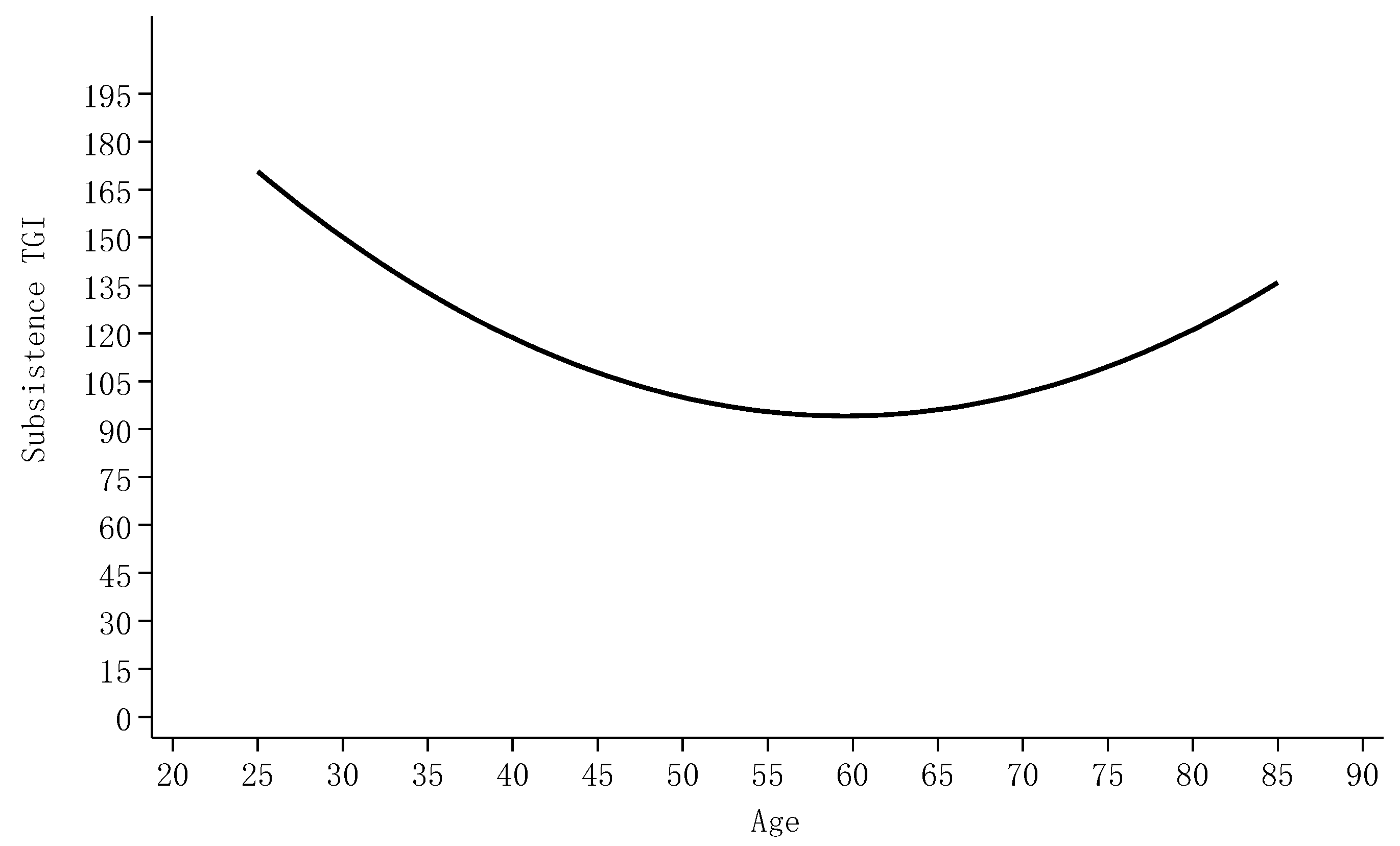

Matzkin, 1991). We anticipate that the impact of age on preferences will likely vary across different life stages. To validate this hypothesis, we plotted the fitting curves for various types of consumption TGIs against age.

Figure 1 illustrates the fitting curve for Subsistence TGI. The graph reveals that consumers’ preference for subsistence consumption initially declines and then increases, with the inflection point occurring around 57 years of age. Given the differences in savings structures and income sources between younger and older individuals, the slope of the curve shows slight variations around this inflection point.

Similarly, consumer preferences for developmental consumption also exhibit a U-shaped relationship (

Figure 2), with the inflection point occurring around 58 years of age. Generally, after age 58, consumers’ preference for developmental consumption shows an increasing trend with age. Compared to the fitting curve for subsistence consumption preferences, the curve for developmental consumption preferences and age is notably flatter.

We employ a micro-econometric model to empirically investigate how consumption preferences evolve across the life cycle. Based on previous research and our preliminary findings, we assume a nonlinear relationship between age and consumption preferences (

Matzkin, 1991). To capture this effect, we incorporate a quadratic term for age into our regression analysis. The model includes both age-related terms to capture life-cycle characteristics and other control variables to account for factors that influence consumption preferences.

In Equation (4), TGIi represents the preference for various consumption categories, AGEi denotes age, and α2 is the coefficient for the quadratic term. Xi is a matrix of control variables; α0 and α1 are the constant term and the coefficient for the explanatory variable, respectively, while β is the coefficient vector for the control variables; μi is the random disturbance term.

To gain a deeper understanding of the life-cycle dynamics of consumer preferences, we extend our baseline model by introducing three moderating variables: gender, income, and number of real estate properties. Our aim is to investigate how these socioeconomic factors influence the nonlinear relationship between age and consumption preferences. We accomplish this by incorporating corresponding interaction terms into the baseline model. For each moderating variable, we include its interaction with both the linear and quadratic terms of age. The empirical model is thus modified as follows:

In Equation (5), Zi represents the moderating variable. This study selects gender, income level, and number of real estate properties to examine their moderating effects. α4 is the coefficient for the linear interaction term, and α5 is the coefficient for the quadratic interaction term, whose changes can reflect shifts in the curve’s slope.

When assessing the impact of the moderating effect, we also need to consider changes in the position of the curve’s minimum point, as shown in Equation (6).

Here, the shift in the curve’s inflection point is entirely contingent upon the moderating variable,

Zi. By differentiating the above equation, we can examine the relationship between the inflection point’s position and the moderating variable, as specifically detailed in Equation (7).

3. Empirical Results

3.1. Validating Subsistence and Developmental Consumption Preferences

3.1.1. Baseline Regression

Table 2 presents the baseline regression results. Columns (1) and (2) show the results without the quadratic term, while Columns (3) and (4) include it. Based on the baseline regression for subsistence consumption, the coefficient for the linear age term is −0.4860, which is significantly negative at the 1% level. The quadratic term’s coefficient is 0.0036, significantly positive at the 1% level, providing preliminary evidence of a U-shaped relationship between age and consumption preferences.

To further confirm this U-shaped relationship within our data range, we conducted a U-test following the method by

Lind and Mehlum (

2010). This involved testing the significance of both the lower and upper bounds of the curve’s slope, as well as the position of the curve’s vertex. The specific results are shown in the lower half of

Table 2. For subsistence consumption, the regression results indicate that the lower bound slope is significantly negative at the 1% level, and the upper bound slope is significantly positive at the 1% level. Crucially, the U-shaped curve’s minimum point falls within the data range. Additionally, the Sasabuchi–Lind–Mehlum test rejects the null hypothesis, confirming a robust U-shaped relationship between subsistence consumption preferences and age.

Regarding the U-shaped relationship observed for subsistence consumption, our regression results show that preferences for subsistence consumption reach their lowest point around 57 years of age. We attribute this phenomenon to shifts in household demographic structure. Caregiving burdens, particularly for the elderly and children, constitute a significant component of household subsistence expenditure. Within a household, internal members engage in appropriate risk and welfare distribution to achieve Pareto optimality (

Harounan & Wahhaj, 2013). Given that 55–58 years is a peak retirement age for Chinese laborers, altruism within consumer households at this stage can trigger voluntary intra-household transfers, where working members transfer resources to non-working members.

Similarly, for developmental consumption, analogous test results confirm a U-shaped relationship between age and preferences for this category. The regression results indicate that consumers’ preference for developmental consumption gradually rises after the age of 65. This increase might be attributed to older consumers’ growing reliance on healthcare-related expenditures as they age, influenced by their changing physical health status. Our findings align with existing research, indicating that the higher spending on developmental consumption by China’s elderly population is driven by their stronger preferences (

Fan et al., 2024).

3.1.2. Robustness Test

To test the robustness of our findings, we included clustered standard errors in the regression model, with the sample clustered at the household level (

Table 3a). The results show that even after clustering, the regression outcomes remain significant at the 1% level, and the direction of the effects does not change. This suggests that our results are robust.

To account for the potential influence of household registration status on consumption preferences, we added a new control variable to our model. This dummy variable, rural, is assigned a value of 1 if the household head has a rural household registration and 0 otherwise. As

Table 3b shows, the regression coefficients of our core explanatory variables remain significant after the inclusion of this variable. This confirms that our findings are not affected by household registration status, serving as a robustness check on our main results.

3.2. Moderation Effect Analysis

We hypothesize that individual consumer characteristics influence the intensity of age’s effect on consumption preferences. Therefore, we selected income level, gender, and number of properties as moderating variables for regression analysis. Since income level and property ownership are often influenced by socio-cultural factors, geographical environment, and economic development, they tend to exhibit clustering effects at the city level. Consequently, we control for fixed effects at the city level in our moderation effect analyses.

3.2.1. Gender Moderation Effect

Extensive existing literature demonstrates the presence of gender differences (

Exley et al., 2025). Furthermore,

Ritzel and Mann (

2021) found that for meat consumption, gender differences in consumption parallel biological development, reaching their peak between 51 and 65 years of age. Given this, we use gender as a moderating variable to observe its role in how age influences consumption preferences.

Based on the regression results presented in

Table 3, gender significantly moderates the effect of age on consumption preferences in two key ways. First, for subsistence consumption, women’s Subsistence TGI is generally lower than men’s, and their decline with age is slower than men’s. As women age, they might increasingly rely on non-market-based subsistence support, such as family assistance, adult child support, or community services. These factors could, to some extent, mitigate the decline in their demand for or reliance on “subsistence” consumption. Men, conversely, might experience a more pronounced drop in their subsistence consumption index as they age, possibly due to changes in employment status or reduced social activities. Second, women’s Subsistence TGI reaches its lowest point around 73.70 years of age, whereas men’s Subsistence TGI reaches its lowest point around 64.64 years of age. This suggests that women’s subsistence consumption patterns or support mechanisms in later life may differ from men’s; they might maintain certain basic living standards more consistently, or their related needs decline more slowly, reaching their nadir at a much older age.

In contrast to subsistence consumption, for developmental consumption, both male and female TGIs reach their lowest point around 55 years of age. Specifically, the female TGI inflection point occurs around 55.86 years of age, which is later than the male inflection point (around 54.90 years of age). This reflects that as women age, they tend to reduce their preference for developmental consumption and shift towards subsistence consumption. This aligns with the traditional view of women’s caregiving roles within the family, which might lead them to curtail spending on developmental consumption.

3.2.2. Income Moderation Effect

Based on the regression results in

Table 4, income level moderates the relationship between age and consumption preferences differently across consumption types.

For subsistence consumption, higher consumer income intensifies the impact of age on consumption preferences. For low-income consumer groups, the effect of age on subsistence consumption preferences shows little fluctuation. This is likely because low-income consumers, constrained by their spending power, largely concentrate on basic survival needs such as food, housing, and daily necessities. Even as they age, their subsistence consumption needs might increase, but due to income limitations, these changes won’t be as significant as for high-income groups. As income continuously increases, the inflection point of the curve shifts to the left. This means that, all else being equal, higher-income consumers exhibit a greater preference for subsistence consumption, consistent with

Frank’s (

1985) findings that expenditure on nonpositional

1 goods constitutes only a small portion of a wealthy person’s income, and thus demand for these goods increases with consumer income.

In contrast, for developmental consumption, the curve’s shape inverts after introducing the income moderating variable. This indicates that, with income as a moderator, consumers show the highest preference for developmental consumption during middle age, when they possess both economic capacity and a drive for development. During youth and old age, preferences are relatively lower, constrained by social resources, consumption motivation, or physiological and psychological needs.

As income level rises, the curve’s peak shifts to the left. This implies that for consumers at the same age stage, higher-income consumers demonstrate lower consumption preferences compared to relatively lower-income consumers. This finding validates previous scholarly theories that, due to “consumption emulation” or “keeping up with the Joneses,” lower-income consumers have a greater demand for positional goods

2 than higher-income consumers (

Frank, 1985).

3.2.3. House Numbers Moderation Effect

The number of houses owned directly influences a consumer’s economic status, wealth accumulation, and liquidity. Consumers with more houses generally possess a more robust accumulation of wealth; these houses serve not only as a symbol of their affluence but also signify greater financial security.

According to the regression results in

Table 5, for both subsistence and developmental consumption, a greater number of houses owned by consumers intensifies the impact of age on their consumption preferences. Integrating this with previous theoretical analysis, individuals typically accumulate and invest in their youth, while in old age, they may reduce asset holdings to support their retirement. For consumers in this category, the relationship between their age and consumption preferences changes more dramatically because they possess the ability to liquidate assets and adjust their consumption structure.

As the number of houses increases, the curve’s inflection point consistently shifts to the right (

Table 6). For subsistence consumption, variations in the number of houses have a more pronounced effect on the inflection point’s displacement. Individuals with more houses typically enjoy higher economic stability, which allows for more deliberate and long-term consumption decisions. These individuals often accumulate wealth over an extended career, meaning that the increase in their consumption preferences tends to manifest later in their life cycle.

3.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

3.3.1. Regional Grouped Regression

China exhibits significant cultural and value differences across its various regions (

Roxby, 1937). These disparities can lead to heterogeneous consumption behaviors (

Schütte & Ciarlante, 1998), which can be understood as variations in consumption preferences. Therefore, this study conducts grouped regressions across 29 provinces, categorized into seven cultural regions, to investigate whether regional heterogeneity in consumption preferences exists.

Our regression analysis reveals that a U-shaped relationship between age and consumption preferences exists across all seven regions for both subsistence and developmental consumption. The effect of age on subsistence consumption preferences is not significant in South China. A potential explanation is that the region has a relatively well-developed commercial and service system, making it more convenient for the elderly to access goods and services. This may render the influence of age on consumption less prominent compared to other regions. Furthermore, we find that for developmental consumption, the effect of age on preferences is also not significant in both South China and Northeast China. In Northeast China, a major region for population outflow, a large loss of young people may have resulted in a consumption market dominated by the elderly. In such a market with a relatively singular consumer base, the influence of age on consumption preferences may no longer be the primary driving factor, as preferences are instead more influenced by other factors such as income and social security. To provide a more intuitive understanding of this regional heterogeneity in consumption preferences, these curves are illustrated in

Figure 3.

For subsistence consumption, the East China region demonstrates a notably higher preference. This region encompasses Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Jiangxi, and Anhui provinces. These provinces are economically developed, particularly the Yangtze River Delta area

3, which serves as China’s economic engine and a frontier for opening up. Residents here enjoy higher disposable incomes and substantial wealth accumulation, leading to potentially greater demands for quality of life and, consequently, elevated consumption preferences. Concurrently, East China boasts a more mature and dynamic consumer market, offering a richer array of consumption choices.

Observing the curves for developmental consumption, regional differences are evident in the inflection point (the bottom of the U-shape). Specifically, the North China region

4 shows an inflection point at 47.6 years of age, while the South China region

5 has an inflection point at 73.3 years of age. The remaining regions fall within the 50–60 age range.

3.3.2. Consumption Category Grouped Regression

To further investigate the time-varying characteristics of consumer preferences for different consumption categories, this study disaggregates consumption into eight major categories for heterogeneity analysis: food, clothing, housing, household equipment and services, transportation and communication, education and entertainment, healthcare, and other consumption. This allows us to explore the differences in expenditure across various consumer groups for each specific category.

According to

Figure 3, the “other consumption” category initially appeared to exhibit an inverted U-shaped curve. However, even after controlling for year and provincial fixed effects, the regression results demonstrate that it still follows a U-shaped relationship.

Columns (1) through (8) of

Table 7 present the regression results for these eight consumption categories. It’s evident that even after controlling for various covariates and fixed effects for year and province, all categories consistently display a U-shaped relationship with age.

As shown in

Figure 4,our calculations reveal significant differences in the inflection points (the lowest point of the U-shaped curve) across these consumption categories: food consumption: approximately 74 years; clothing consumption: approximately 74 years; housing consumption: approximately 65 years; household equipment and services consumption: approximately 64 years; transportation and communication consumption: approximately 76 years; education and entertainment consumption: approximately 62 years; healthcare consumption: approximately 41 years; other consumption: approximately 54 years.

Notably, healthcare consumption has the earliest inflection point, occurring around 41 years of age. We posit that as individuals enter middle age, their overall health is generally robust, and the risk of chronic or major diseases has not yet significantly increased, leading to a trough in healthcare expenditure during this life stage. However, starting around age 41, individuals’ “health capital” gradually depreciates, necessitating increased household expenditure on health check-ups, medication, and rehabilitative treatments. Thereafter, as age further advances, healthcare demands extend beyond curative spending to include preventive health management and long-term care expenditures. Consequently, consumption in the healthcare category continuously increases with age after approximately 41 years.

3.3.3. Income Level Grouped Regression

To better understand how the effect of age on consumption preferences differs across income levels, we conducted a sub-group analysis. We divided the sample into high- and low-income groups based on the median income and performed separate regressions for each. The results are presented in

Table 8, and the relationship between age and consumption preferences is shown graphically in

Figure 5.

Upon closer analysis of the income groups, we find that the coefficients for age and age-squared are both insignificant for developmental consumption in the low-income group (

Table 9). This suggests that due to budget constraints, their spending on developmental consumption is not systematically influenced by age, but rather by current income or unforeseen events. This finding aligns with the economic theory of consumption elasticity, which posits that the lower the income, the lower the consumption elasticity. Regarding subsistence consumption, the curve for the high-income group is steeper, with larger absolute values for the age and age-squared coefficients. This implies a more pronounced change in their subsistence consumption preferences across life-cycle stages. When young, they may be more inclined to use their income for investments or non-subsistence consumption. However, in old age, their greater purchasing power allows them to pursue higher-quality medical and elderly care services, which leads to a greater magnitude of change in their consumption preferences.

4. Discussion

This study’s empirical findings significantly contribute to our understanding of consumption dynamics in aging societies, particularly by revealing the complex, time-varying nature of consumer preferences across the life cycle. Our most prominent discovery is the consistent U-shaped relationship between age and consumption preferences for both broad categories of subsistence and developmental consumption, as well as across almost all disaggregated consumption types. This finding challenges a simplistic view of declining consumption with age or a purely “hump-shaped” consumption expenditure (

Carroll, 1994), instead suggesting a period of diminished preference in middle age followed by a resurgence in later life. While

Modigliani and Ando (

1963) posited consumption smoothing, our results indicate that preferences, distinct from smoothed expenditure, undergo a more nuanced, non-monotonic evolution. The inflection points identified (around 57 for subsistence and 58 for developmental consumption) mark crucial transition ages where preferences shift from decline to increase.

The aggregated evidence from these robust empirical tests, consistently demonstrating an increasing consumption preference among the elderly with age, challenges the prevalent notion of consistently low consumption levels in older populations. This perspective suggests that the ongoing process of population aging, particularly in China, may not necessarily be a drag on domestic consumption but could, in fact, exert a positive influence on overall consumption volume as preferences for various goods and services rise in later life.

These findings carry significant implications for both policy-makers and businesses. For governments, our research reveals that with increasing age, the share of subsistence consumption allocated to healthcare significantly increases. This finding leads us to two key policy recommendations. First, the government should prioritize improving the coverage and reimbursement rate of medical insurance for the elderly. Second, it should establish a multi-tiered elderly healthcare service system to help alleviate their financial burden. In addition to healthcare, we recommend that the government strengthen services such as elderly education and training, cultural tourism, fitness and leisure, and financial support. Policymakers should also expand the elderly care products industry to cater to the daily needs, rehabilitation, and nursing of the aging population. By leveraging technological innovation, smart products and services can be developed to benefit a greater number of elderly people. For businesses, the research highlights opportunities for developing age-appropriate products and services, particularly in areas like healthcare, leisure, and quality-of-life improvements that resonate with the preferences of an aging population. Marketing strategies should acknowledge the diverse preferences within the elderly demographic, moving beyond a monolithic view.

The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some limitations. Due to database constraints, our current study is restricted to data on household consumption in China. Nevertheless, we believe the patterns identified herein have broad applicability. Our findings and policy recommendations can serve as a valuable reference for other developing countries that share similar national characteristics with China.

Future research could delve deeper into the specific drivers behind the observed U-shaped patterns, perhaps incorporating psychological factors, detailed health trajectories, and longitudinal data to track individual consumption changes more precisely. Exploring the impact of varying pension systems, eldercare infrastructure, and intergenerational wealth transfers on these preferences would also yield valuable insights. Furthermore, comparative studies across different aging economies could reveal universal patterns versus context-specific variations. Finally, we also consider the influence of generational cohorts on consumption preferences. A given generation may form unique consumption preferences due to factors such as historical context and social changes.

5. Conclusions

Understanding the life-cycle dynamics of individual consumption preferences is crucial for investigating how population aging impacts a society’s overall consumption structure. This is because the aggregated consumption patterns of a society are shaped by how individual preferences evolve with age. Using historical consumption data, we measured consumer preferences with the Target Group Index (TGI) to analyze how individual consumption across various categories changes throughout the life cycle.

Our empirical findings reveal that in China, consumption preferences exhibit time-varying characteristics across the life cycle. For both subsistence consumption and developmental consumption, consumer preferences demonstrate a U-shaped trend as age increases.

Furthermore, we found that elderly women tend to prefer subsistence consumption more than elderly men. For subsistence consumption, higher income intensifies the influence of age on consumption preferences. Conversely, for developmental consumption, middle-aged individuals show a greater preference. Additionally, the more properties a consumer owns, the more pronounced the impact of age on their consumption preferences.

In our subsequent heterogeneity analysis, we discovered variations in consumer preferences across different cultural regions within China. Moreover, from a consumption category perspective, all seven categories, except “other consumption,” also exhibited a U-shaped trend. Lastly, our findings indicate that age does not have a significant effect on the developmental consumption preferences of low-income consumers.

Through a series of robust empirical tests, this study demonstrates that elderly individuals’ consumption preferences continually increase with age. This finding challenges the traditional perception of low consumption levels among the elderly, suggesting that the process of population aging may, in fact, have a positive impact on overall consumption.