Abstract

The collaborative economy is experiencing a remarkable surge, offering vast potential for growth. Consequently, this burgeoning movement has become a focal point of interest in the realm of entrepreneurship. However, numerous unexplored or inadequately addressed research gaps persist, leaving us without a well-defined paradigm for what we can term the entrepreneurial collaborative economy. In light of these challenges, this study embarks on a quest to bridge these gaps through a comprehensive systematic literature review. Two research objectives guided our endeavor: (1) mapping the literature related to the collaborative economy in the field of entrepreneurship to propose a research taxonomy, and (2) analyzing areas in this field that warrant further research. Our literature review, conducted using the PRISMA methodology, yielded 407 studies. Employing advanced textometric techniques, we uncovered a research taxonomy consisting of three distinct clusters within entrepreneurial collaborative economy studies. In particular, our investigation has unveiled that the entrepreneurial collaborative economy paradigm remains in a state of emergence within the academic literature. The paper concludes with thought-provoking discussions and key insights.

1. Introduction

Collaborative economy (CE), also known as the sharing economy or peer-to-peer economy (Palátová et al., 2023), has emerged as a dynamic socio-economic phenomenon in which individuals and organizations directly share resources, goods, services, or information, primarily through digital platforms (Akande et al., 2020; Dabbous & Tarhini, 2021; Hellwig et al., 2015). It offers a compelling alternative to traditional centralized models of consumption and production, emphasizing decentralized and community-driven interactions, all without the need for intermediaries (Mont et al., 2020; Wirtz et al., 2019).

Although the roots of the CE phenomenon extend beyond the present, the rapid proliferation of social networks and mobile devices has accelerated its growth (Pouri & Hilty, 2021). The term “collaborative consumption” was first coined in a 1978 study (Felson & Spaeth, 1978), defining it as “the efforts by people to engage in joint activities with others” (Menéndez-Caravaca et al., 2021). Subsequently, influential movements such as the free and open-source software movement focused on collaborative software design (Gamalielsson & Lundell, 2014).

Today, many digital collaborative platforms and apps spanning diverse industries facilitate peer-to-peer transactions in innovative ways (Cheng et al., 2021). These platforms engender trust among participants, offering the mechanisms needed for seamless interaction and business transactions (Ert et al., 2016). Prominent examples include: (1) Airbnb, which enables individuals to rent their homes or rooms to travelers, (2) Lyft or Uber, ride-hailing apps connecting drivers with passengers, (3) BlaBlaCar a popular European app connecting drivers with empty seats to passengers traveling in the same direction, and (4) Turo, a car rental platform allowing owners to rent their vehicles when not in use. Such platforms and apps reduce the need for ownership and lower environmental footprints (Belk, 2014; Ertz & Boily, 2019; Y. Wan et al., 2022), promoting more sustainable and efficient resource utilization (Govindan et al., 2020; Koul et al., 2022; Toni et al., 2018).

In this dynamic milieu, entrepreneurial initiatives have begun to flourish. Entrepreneurship, characterized by the identification, creation, and pursuit of opportunities to develop new products, services, or businesses in the CE, plays a pivotal role (Honig, 1998; T. Zhang et al., 2019). It acts as a catalyst for growth and innovation in CE (Ince et al., 2023; Yun et al., 2019), stimulating creativity, uncovering new opportunities, and contributing to job creation and economic development (Karami & Read, 2021). In addition, the CE offers an array of uncharted territories ripe for exploration, where entrepreneurs can provide innovative solutions. In this context, the concept of entrepreneurial orientation has emerged as a means to infuse entrepreneurial behavior into existing firms, encompassing traits such as innovativeness, proactiveness, competitive aggressiveness, risk-taking, and autonomy (Pearce et al., 2010; Tuan, 2017). In fact, CE, entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial orientation are naturally connected, as they share a common foundation in innovation, value creation, and the pursuit of opportunities. In turn, entrepreneurial orientation enhances the ability to identify and seize those opportunities within the collaborative ecosystem. In this way, entrepreneurs contribute to the CE by promoting open international competition where customers can freely access and exchange goods and services, thereby enhancing individual and collective well-being (Papaoikonomou et al., 2022).

Despite the potential of entrepreneurship in the CE, no comprehensive paradigm exists that can be termed “entrepreneurial collaborative economy”. The current research landscape in this domain remains fragmented and challenging to navigate. However, in this study, we do not intend to introduce a new theoretical paradigm, but rather to adopt this expression as an analytical lens to examine how entrepreneurial principles operate within CE contexts. In this notion, we aim to better understand how opportunity recognition, innovation, and value creation emerge when entrepreneurial actors engage with CE platforms and practices.

In this manner, on the one hand, digital platforms play a central role, not only by matching supply and demand efficiently but also by enabling new forms of governance, scalability, and innovation in resource utilization. On the other hand, entrepreneurship encompasses the processes by which individuals or organizations identify opportunities, mobilize resources, and take calculated risks to create and capture value. When applied to CE contexts, entrepreneurial activity becomes a key driver for platform creation, innovative business models, and the diversification of collaborative practices beyond consumption to include production, financing, and service provision. Thus, the intersection of these two domains warrants systematic analysis, as it reveals how entrepreneurial mindsets and behaviors can shape, expand, and sustain CE ecosystems.

Consequently, this study aims to fill this gap by conducting a systematic literature review, with a twofold purpose: (1) mapping the literature related to the CE in the field of entrepreneurship to propose a research taxonomy, and (2) analyzing in this field the areas that warrant further research. This systematic literature review, conducted using the PRISMA methodology, identified 407 relevant studies. In addition, textometric analysis, facilitated by the IRAMUTEQ software (Version 0.7 Alpha 2), enhanced our understanding of the CE’s rapid expansion. Taken together, these lenses not only provided a well-structured understanding of the CE’s evolution but also contributed a comprehensive foundation for identifying approaches and guiding future research in this domain.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the background of the CE, establishing the groundwork for defining the scope of the entrepreneurial collaborative economy. Section 3 presents the PRISMA methodology and outlines the research design. Section 4 presents the results of the textometric analysis. Section 5 delves into the discussions of the results, while Section 6 concludes with implications and directions for future research.

2. Collaborative Economy Background

The CE has directly impacted the redefinition of strategies of a large number of companies (Chuah et al., 2021). Companies of diverse sizes and backgrounds have embraced digital platform-based models to join the CE, although not all with the same degree of success (Hazée et al., 2020). In general, CE-connected enterprises harness digital platforms to establish connections with individuals or entities, offering more efficient ways for acquiring goods and services (Weber, 2016). Consequently, CE opens up new opportunities for individuals and companies (Thornton, 2024).

The CE is considered a heterogeneous phenomenon encompassing a wide array of economic activities (Gruszka, 2017; Gurău & Ranchhod, 2020). It amalgamates different modes of consumption, production, and labor, including collaborative consumption, collaborative production, collaborative finance, collaborative knowledge, collaborative value co-creation, gig economy, and collaborative governance (Bogatyreva et al., 2021; Menéndez-Caravaca et al., 2021; Mouazen & Hernández-Lara, 2023; Ravenelle, 2019). In this domain, value co-creation is typically mediated by digital platforms that enable peer-to-peer interactions, facilitate trust through transparent information systems, and allow for flexible resource allocation across diverse participants. Moreover, governance mechanisms in CE platforms often distribute decision-making power, granting users an active role not only as consumers or providers but also as co-designers of services and experiences. By framing value co-creation within the CE, we emphasize these dynamics, which integrate technological intermediation, shared governance, and network effects as key enablers of sustained value creation.

2.1. Collaborative Consumption

Collaborative consumption stands out as one of the most well-known phenomena of the CE (Hallem et al., 2020). This socio-economic model redefines ownership by encouraging individuals and organizations to share access to goods and services, facilitated by community-based online platforms (Anwar, 2023; Hamari et al., 2016). Recent technological advancements, evolving consumption patterns, heightened consumer demand, and shifting consumer preferences have fueled the significant growth of this movement (Barnes & Mattsson, 2017; de Rivera et al., 2017; Dreyer et al., 2017; Minami et al., 2021; Perera et al., 2023). Collaborative consumption relies on the principle that underutilized assets, such as cars, homes, tools, clothes, and skills, can be efficiently shared or rented, resulting in enhanced efficiency, reduced waste, cost savings, all while reducing the environmental footprint (Hamari et al., 2016). This disruption has challenged conventional industries, fundamentally altering the notions of ownership and access to goods and services, with implications spanning society, the economy, and the environment (Guillen-Royo, 2023). Collaborative consumption emerges as a sustainable alternative to conventional consumption (Belk, 2014), manifesting notable in the growth of digital platforms for clothing rental and second-hand resale in the fashion industry (Arrigo, 2021) and the emergence of ride-sharing in the transportation sector (V. M. de Oliveira et al., 2022).

2.2. Collaborative Governance

Collaborative governance has witnessed remarkable growth in diverse CE domains, such as environmental protection (Ge et al., 2023; Shao et al., 2023), emergency (Tangney et al., 2023), transportation (Tiglao et al., 2023), food (Lelieveldt, 2023; Sundqvist-Andberg & Åkerman, 2022), and sustainability (Allal-Chérif et al., 2022; Glass et al., 2023). It embodies the practice of collaborating with various stakeholders to collectively make decisions, striving for optimal utilization of knowledge and resources (Bendell et al., 2011; Noh & Yashaiya, 2019; Sun, 2015). The main objective of collaborative governance is to achieve better use of knowledge and resources in a more efficient way, combining the diversity of perspectives of stakeholders, such as government, organizations, companies, social community groups or individuals, to develop solutions that satisfy all groups or are best for the common well-being (Lou et al., 2022; Saraswati et al., 2023). Collaborative governance hinges on fostering negotiation processes where participants collectively make decisions, set objectives, and formulate policies and strategies (Paliokaitė & Sadauskaitė, 2023).

2.3. Collaborative Production

Prior research has identified collaborative production in areas as diverse as agriculture (Alimohammad et al., 2022), manufacturing (Ding et al., 2021), transport (Tiglao et al., 2023), robotics (Malik & Brem, 2021), online communication (Dwyer, 2011), and food (Maheshwari et al., 2022). It comes to life when multiple individuals or organizations work together to create a product or develop a service (Zang et al., 2004), thereby adding value to customers (Selim et al., 2008). Each participant contributes their specific expertise to the project, with a coordinator ensuring efficient production processes (Bouaziz et al., 2022), informed decision making, and cost-effective outcomes (Vargas et al., 2016).

2.4. Collaborative Finance

Collaborative finance, also known as peer-to-peer finance, has grown significantly in the last decade (Menéndez-Caravaca et al., 2021), notably driven by the proliferation of crowdfunding (Ansart & Monvoisin, 2017). This form of finance brings together individuals or companies to raise funds from a multitude of contributors, each providing modest sums (Berné-Martínez et al., 2021). Collaborative finance is frequently used to develop projects with social or environmental goals (Bárcena-Ruiz & Sagasta, 2021; Jin et al., 2019; Moraux et al., 2023). Platforms like Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and GoFundMe offer innovative financing alternatives, challenging traditional financial institutions (Panjwani & Xiong, 2023; Tian et al., 2021; Yu & Xiao, 2023). Yet, collaborative finance platforms face challenges related to regulation, trust, and sustainability, where blockchain stands as a potent solution (X. Wan et al., 2023), facilitating decentralized value generation (Ren et al., 2023; Viano et al., 2023).

2.5. Collaborative Knowledge

Collaborative knowledge refers to the activities developed jointly by a group of individuals or organizations to build a collective and shared understanding, information, or expertise (Wang, 2011). It encompasses a myriad of approaches, including meetings, discussions, shared documents, or digital collaborative tools, serving as a crucible for problem-solving, decision-making, and innovation (Beaudoin et al., 2022). This collaborative movement transcends geographical boundaries and time zones, enabling seamless cooperation (Saleh Al-Omoush et al., 2021). Prior research has explored collaborative knowledge’s impact from diverse perspectives on areas such as cooperative learning environment (Tan & Chen, 2022), supply chain agility, and corporate sustainability, as well as employee productivity (Dong et al., 2023; Heerwagen et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2020; Mensah & Enu-Kwesi, 2018).

2.6. Collaborative Value Co-Creation

Collaborative value co-creation emphasizes the collaborative processes through which customers, companies, and other stakeholders collaboratively generate and develop economic and social value (Ostertag et al., 2021). Placing customers at the center of the value creation process results in products and services tailored to individual needs (Lee et al., 2023; Song et al., 2023). This movement recognizes that customers possess unique needs, preferences, and expectations, empowering them to actively shape the value derived from products and services (Jia et al., 2023). This collaboration unfolds through diverse avenues, including social media, online communities, feedback mechanisms, and face-to-face interactions (Li & Tuunanen, 2022). Collaborative value co-creation offers companies new business models based on innovations, relying on continuous feedback, advocacy, information sharing, and learning (Guo et al., 2023). Gathering insights and data from customer interactions plays a pivotal role in enhancing offerings and bolstering the value co-creation process (Cao et al., 2022), making it an essential factor in attracting financing and boosting project success rates (Su et al., 2021).

2.7. Gig Economy

The CE exerts a substantial influence on the work landscape (Arriagada et al., 2023), exemplified by the emergence of the gig economy. Characterized by short-term, freelance work arrangements (Mouazen & Hernández-Lara, 2023), this phenomenon has been fueled by technological advancements (Bögenhold et al., 2017). Individuals increasingly engage in project-based work as independent contractors rather than being permanent employees of a single company (Adams et al., 2018; Bogatyreva et al., 2021; Ravenelle, 2019). The gig economy provides them the flexibility to choose when or where they work (T. Zhang et al., 2019), supplementing their income (Honig, 1998), offering opportunities to those facing traditional employment barriers (Pedersen & Netter, 2015), and nurturing entrepreneurship (T. C. Zhang et al., 2018).

3. Literature Review Methodology

In this section, we delve into the methodology employed for our literature review, specifically adopting a systematic approach. It is crucial to distinguish between a narrative literature review and a systematic literature review, as highlighted by (Parums, 2021). Unlike a narrative review, which selects the evidence for synthesis in a non-reproducible manner without the need for an exhaustive search (Ferrari, 2015), a systematic literature review “aims to comprehensively locate and synthesize research that bears on a particular question, using organized, transparent, and replicable procedures at each step in the process” (Littell et al., 2008). This systematic approach contributes to promoting transparent reporting of research (Sarkis-Onofre et al., 2021) while ensuring the consistency and comprehensiveness of our research (Kamali Saraji & Streimikiene, 2023).

To carry out this systematic literature review, we adopted the PRISMA methodology. PRISMA is renowned for its robustness when conducting systematic literature reviews, as acknowledged by (Moher et al., 2009, 2010). Although initially proposed for the field of medicine, PRISMA has found widespread application in various fields conducting systematic literature reviews (Panic et al., 2013; Peixoto et al., 2021; Rethlefsen et al., 2021). PRISMA was proposed in 2009 (Liberati et al., 2009), and since then, it has evolved to align with the latest advancements in knowledge. In fact, the most recent protocols for the implementation of this technique were published in 2020 (Page et al., 2021). In 2021, the PRISMA guideline was incorporated to enhance bibliographic searches (Rethlefsen et al., 2021).

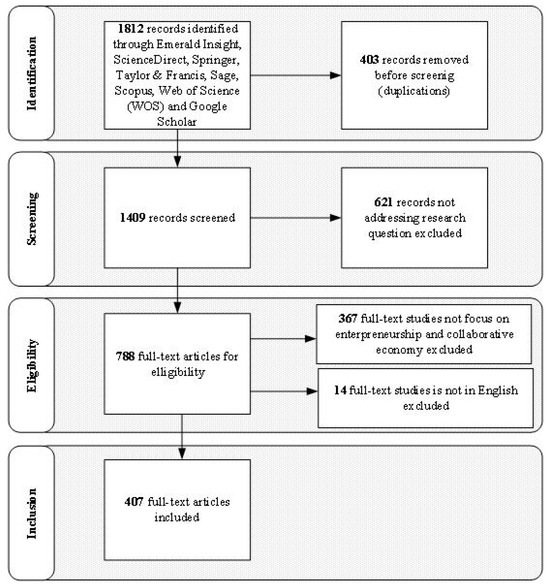

PRISMA guides the systematic literature reviews through a checklist of 27 items spanning four phases: (1) identification, (2) screening, (3) eligibility, and (4) inclusion (Liberati et al., 2009). This structured approach enables the transparent justification of the inclusion and exclusion of studies within the literature review (Zhao & Taib, 2022). In our study, the peer-reviewed articles that served as the primary source of information for our systematic review came from the following databases: (1) Emerald Insight, (2) ScienceDirect, (3) Springer, (4) Taylor & Francis, (5) Sage, (6) Scopus, (7) the Web of Science, and (8) Google Scholar. Figure 1 summarizes the number of papers incorporated or excluded in each phase, as well as the count of studies finally included in our analysis. It is worth noting that all PRISMA protocols were strictly adhered to.

Figure 1.

PRISMA application.

In this context, to ensure a comprehensive coverage of the literature on the intersection between the CE and entrepreneurship, we selected these multiple databases spanning different disciplinary areas, including social sciences, business and management, and information technology. This diversity of sources minimized the risk of omitting relevant studies, given the interdisciplinary nature of the topic. Also, the application of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria ensured that only relevant and high-quality publications were retained for analysis. The initial search results were imported into reference management software, where duplicates were automatically identified and removed. A subsequent manual review was conducted to confirm the elimination of all duplicate entries, ensuring the integrity of the final dataset.

Building upon the conceptual framework developed in the preceding section of this article, our search strategy encompassed terms related to CE and entrepreneurship, embracing all economic activities associated with this phenomenon. These terms included: (1) Collaborative Economy, (2) Collaborative Consumption, (3) Collaborative Knowledge, (4) Collaborative Finance, (5) Collaborative Governance, (6) Value Co-creation, (7) Collaborative Production, (8) Gig Economy, (9) Sharing Economy, (10) Peer-to-peer Economy, and (11) Entrepreneurship. Given the breadth of these terms, the incorporation of search operators was key to effectively identifying relevant papers. Consequently, we employed the search operators such as AND, OR, and “*”, in combination with the symbols [ ] and “”, to construct the following search query:

[“Collaborative Economy” OR “Collaborative Consumption” OR “Collaborative Knowledge” OR “Collaborative Finance” OR “Collaborative Governance” OR “Value Co-creation” OR “Collaborative Production” OR “Gig Economy” OR “Shar* Economy” OR “Peer-to-peer Economy”] AND [Entrepreneur*].

This meticulously crafted search string reflects the breadth of terms associated with the CE, as well as the diversity of economic activities linked to this phenomenon. As a result, the initial phase of our search identified 1812 articles, with 403 duplicates identified and excluded before starting the screening phase. Subsequently, during the screening phase, 621 articles were eliminated as they did not align with our research objectives. This phase involved a comprehensive analysis of titles, abstracts, keywords, and introduction sections. In the eligibility phase, we conducted a more rigorous examination, leading to the removal of 367 articles that did not jointly explore the topics of CE and entrepreneurship, along with 14 articles not written in English. Ultimately, our analysis encompassed 407 articles.

4. Results

In this section, we present the outcomes of our analysis, which was conducted using the Iramuteq (Interface for Multidimensional Text Analysis and Questionnaires) software(Version 0.7 Alpha 2). Iramuteq, a Python-based tool (Version 3.11) built on the foundations of the R statistical software (Version 4.2.3) package and distributed under the GNU license, serves as our primary textometric analytical instrument. Leveraging the chi-square test (χ2), this software allows us to delve into the multidimensional aspects of our textual data. In starting our analysis, we followed the guidelines provided by (Sousa, 2021), particularly employing the Alceste method (Marpsat, 2010). To prepare the corpus for analysis, we meticulously constructed a source file in UTF-8 encoding. In this file, each of the 407 articles included in our systematic literature review must be separated into distinct lines, with each article preceded by **** * (for example, **** *Article1). Our textometric analysis incorporated the following: (1) title, (2) abstract, and (3) keywords. Our analyses encompassed three key facets: (1) lexicometric analysis, (2) similarity analysis, and (3) clustering analysis.

4.1. Lexicometric Analysis

The lexicometric analysis serves as the starting point of the analysis, enabling us to gain insights into the dataset’s (words) structural composition. Iramuteq allows distinguishing between active words, such as nouns, adjectives, and verbs, that appear multiple times in the corpus, and supplementary words, like prepositions and connectors. Achieving this distinction requires a lemmatization process, where we identify the root of a word, eliminating the inflections (Mendes et al., 2019). This lemmatization process is crucial for subsequent clustering analysis. Table 1 shows a summary of this lemmatization process, and Table 2 incorporates the 100 most frequently occurring words in the corpus, ranked by frequency.

Table 1.

Preliminary analysis after lemmatization.

Table 2.

The 100 most frequently used active words.

4.2. Similarity Analysis

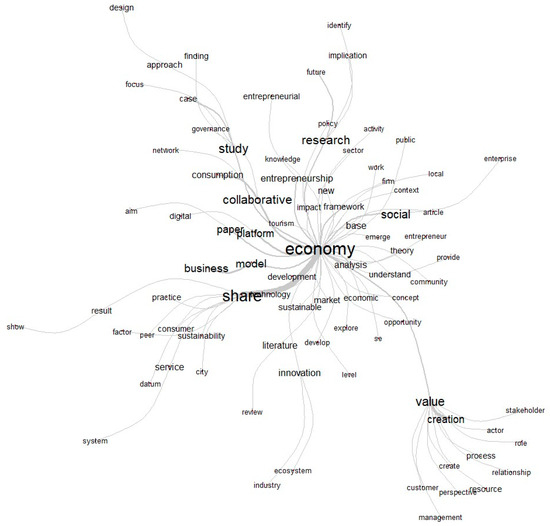

Similarity analysis offers a graphical representation of the conceptual organization within our textual corpus, depicting it as a network of active forms (Sousa, 2021). This analysis focuses on the co-occurrence of active forms across the entire textual corpus (Salviati, 2017). In particular, we employ a graph-based approach, where the nodes and their connections are determined by their co-occurrence in the same text, assessed through the chi-square of association test (Degeneve et al., 2022). Figure 2 illustrates the output developed by Iramuteq for this similarity analysis, emphasizing words with a frequency greater than 100 for clarity.

Figure 2.

Similarity analysis graph.

For proper interpretation of this graph, it is essential to consider both font size and line thickness (Bueno et al., 2021). Larger font sizes indicate stronger co-occurrences, while thicker lines represent more intense relationships. Specifically, Figure 2 showcases “economy” as the central active form in our textual corpus, closely linked to the lemmatized form “share” with “value” and “creation” standing out prominently among the rest of the incorporated words.

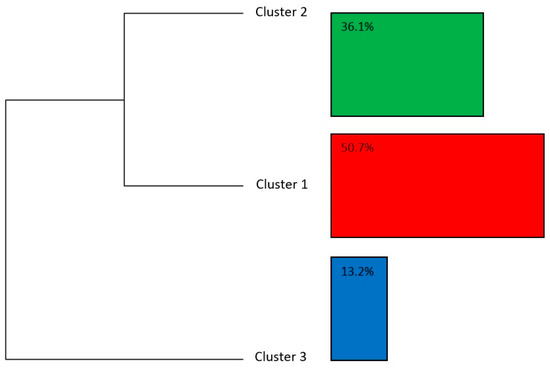

4.3. Clustering Analysis

This analysis aims to achieve a dual clustering: one for words and another for articles. Our clustering analysis leverages the Descending Hierarchical Classification technique based on Reinert’s method (Reinert, 1990), an approach that enhances internal similarity of active forms within topical clusters while highlighting the deviations between such clusters (R. P. de Oliveira et al., 2022). To ensure the robustness of our results, we adopted an algorithm’s stopping criterion, mitigating issues of reliability and validity in text analysis (Mondragon et al., 2022).

Executing this method with Iramuteq entails following established values recommendations. We consider three crucial premises (Apaolaza-Llorente et al., 2023): first, setting the expected value of the active form greater than 3; second, conducting a chi-square value test against the cluster, with χ2 ≥ 3.89 (p = 0.05) and df = 1; and third, ensuring a minimum threshold of 50% for the frequency of an active form within a cluster. This process involves five key steps (Mondragon et al., 2022): fragmenting the textual corpus into segments, identifying the presence of complete active forms in each segments, constructing a contingency table to distribute vocabulary per segment, creating a squared distances matrix from this table based on shared active forms, and adopting a descending hierarchical cluster solution that best distinguishes vocabulary segments. The result of this analysis is shown in Figure 3, which presents a dendrogram revealing three distinct clusters of active forms. For a deeper understanding of each cluster’s composition, Table 3 highlights the most significant active forms (p < 0.001) within each group.

Figure 3.

Dendrogram. Cluster analysis. Lexical clusters.

Table 3.

Cluster Composition. The 30 most impacted words per class (excluding verbs and basic words).

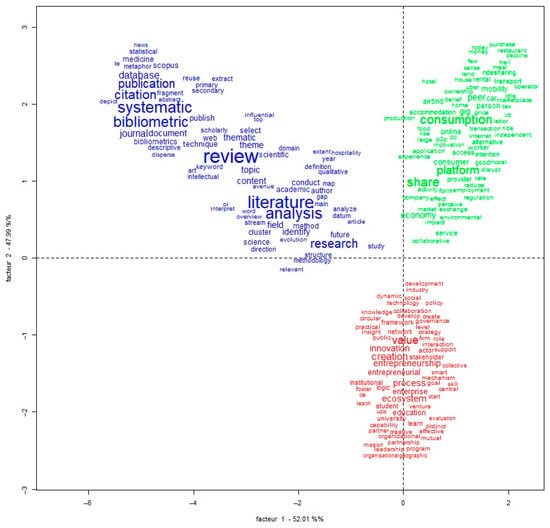

In addition to the clustering analysis, we complemented our investigation with a factorial correspondence analysis (FCA). This graphical representation further enhances our comprehension of the previous results. As depicted in Figure 4, FCA identifies the relationships between clusters, providing an insightful perspective on our clustering analysis results (Hirschfeld, 1935). It is important to interpret this chart by considering the axes in opposition (Salviati, 2017). Specifically, Cluster 1 is represented in red, Cluster 2 is in green, and Cluster 3 is in blue.

Figure 4.

Factorial correspondence analyses (FCA) graph.

5. Discussions

The textometric analysis undertaken in this study revealed the growing interest in the subject of entrepreneurial collaborative economy. Despite the challenge of conducting a systematic literature review on this topic due to the absence of a clear paradigm, we have successfully categorized the studies on this phenomenon into three distinct clusters, representing a conglomerate of diverse economic activities. These clusters, which we will delve into next, offer valuable insights into the entrepreneurial collaborative economy.

5.1. Cluster 1: Innovative Ecosystems for Value Co-Creation

The largest of the three clusters, Cluster 1, encompasses 50.7% of the active words and is associated with 42.8% of the articles analyzed. It prominently features the following: (1) value, (2) creation, (3) process, (4) ecosystem, (5) innovation, and (6) entrepreneurship. We aptly name this cluster “innovative ecosystems for value co-creation”.

In essence, this cluster underscores the impact of the CE as an ecosystem for co-creating value through innovative endeavors. Co-creation, as defined by Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004), involves the collaborative co-creation of new products or services by various stakeholders, including customers, managers, and employees. Widjojo et al. (2019) further highlight the development of collaboration networks with external agents as drivers of value co-creation and innovative deployment.

Co-creation in the context of CE has been examined from multiple perspectives and across various fields. For instance, Simone et al. (2017) provide evidence of peer-to-peer as an emerging ecosystem amplifying value co-creation through service logics. Moreover, studies have explored co-creation’s impact on customer satisfaction dimensions (Díaz-Méndez & Gummesson, 2012; Nájera-Sánchez et al., 2022; Shin, 2016). Factors influencing customer satisfaction in collaborative consumption, such as platform reliability, platform responsiveness, vendor competence, vendor empathy, and co-sharer’s empathy, have been identified (Lin et al., 2020). Nadeem et al. (2021) suggest that value co-creation results from the effect of customer satisfaction on consumer engagement in this type of commerce. (Valdez-Juárez et al., 2021) highlight the significant role of customer satisfaction in electronic commerce in open innovation environments.

From an entrepreneurial perspective, Ratten (2020) highlights the rise of social policies aimed at entrepreneurial solutions for overcoming crises like COVID-19, fostering value co-creation. Tuan (2017) corroborates entrepreneurship’s role in boosting customer value co-creation. Studies related to the gig economy, prominently included in this cluster (Chandna, 2022; Massi et al., 2020), underline the gig economy’s contribution to entrepreneurship (Ravenelle, 2019). Barrios et al. (2022) affirm the incorporation of CE-linked business platforms in the local economy in the United States, triggering interest in new entrepreneurial businesses related to the gig economy. Mouazen and Hernández-Lara (2023) demonstrate the positive impact of the gig economy ecosystem on women’s entrepreneurship. Additionally, Bogatyreva et al. (2021) emphasize the gig economy’s significant and positive impact on entrepreneurial intentions.

The formation of stakeholder relationships, as highlighted by Shams and Kaufmann (2016), plays a pivotal role in structuring entrepreneurial co-creation. Abhari et al. (2019) concur, affirming that entrepreneurship enhances opportunities for idea sharing. Leick et al. (2022) go further, asserting that individual attributes are linked to entrepreneurial activities within the CE, with competencies enhanced in socialization, cooperation, and innovation transfer (Wala & Salmen, 2022).

Cluster 1 also incorporates studies detailing entrepreneurial activities within the CE, especially in emerging economies. Wu et al. (2022) provide evidence of inclusive entrepreneurial activities in China reducing poverty through the shared economy. Boafo et al. (2022) assert that entrepreneurial activities related to the sharing economy in Sub-Saharan Africa promote exports and internationalization. Laakkonen et al. (2019) observe a collaborative business network between forest entrepreneurs, facilitating the integration of intangible resources, enabling the development of novel forest services. Lastly, Widjojo et al. (2019) reveal the presence of collaboration networks in an Indonesian organic community, driving resource integration, forming value co-creation platforms, and leading to innovation in product, process, marketing, and organization.

5.2. Cluster 2: Sharing Economy Platforms in Entrepreneurial Contexts

Cluster 2 is the second largest cluster, accounting for 36.1% of the active forms and linked to 38.46% of the analyzed articles. Dominant terms in this cluster include: (1) consumption, (2) share, (3) platform, (4) peer, and (5) economy, leading us to designate it as “sharing economy platforms in entrepreneurial contexts”.

Given the digital nature of most CE activities, the sharing economy serves as a strategic avenue for global entrepreneurial opportunities (Anwar, 2023). Sahut et al. (2021) assert that digital entrepreneurship should be analyzed in association with digital business models, the digital entrepreneurship process, and the creation of digital startups, digital platforms, and ecosystems. Baranauskas and Raišienė (2022) argue that accelerated digitalization of the economy and digital entrepreneurship have promoted a transition of traditional business models into networked and integrated digital platform models.

Sharing economy platforms, in general, are expected to provide new entrepreneurship opportunities (Gössling & Michael Hall, 2019). Bonamigo et al. (2022) offer valuable guidance for entrepreneurs on selecting collaborators to compose value co-creation platforms, enhancing startup performance. Abhari et al. (2019) underline the platform design’s significance in attracting diverse contributors for collaborative innovation. Koul et al. (2022) highlight the role of new digital platforms for peer–peer models, enabling collaborative utilization of transportation resources with important implications for value co-creation by entrepreneurs.

Grinevich et al. (2019) confirm that sharing platforms can grow by flexibly incorporating green, economic, and social logics. D. T. de Oliveira and Cortimiglia (2017) propose a conceptual framework for value co-creation in web-based multisided platforms, enhancing our understanding of the co-creation phenomenon. Atsız and Cifci (2022) identify two motives and eight dimensions to join the sharing economy: (1) social and cultural motives (the gratification of hosting, altruism, source of cultural capital, and social interaction) and (2) economic motives (monetary, facilitators, network, and independence).

Collaborative consumption entrepreneurs, as identified by Barnes and Mattsson (2016), build tribal communities by matching supply and demand in an innovative way, mainly using social media. Leick et al. (2022) analyze individual–contextual determinants of entrepreneurial service provision within platform-based CE, exploring regional and national influences on urbanization. Roh (2016) suggests that innovative and proactive sharing economy platforms can enable new business models for social entrepreneurship, even bringing in women entrepreneurs (Johnson & Mehta, 2022). In a similar manner, Mouazen and Hernández-Lara (2023) provide evidence of the positive influence of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and gig economy on women’s entrepreneurship.

Some studies within this cluster focus on crowdfunding platforms, a topic immediately related to entrepreneurship. Fehrer and Nenonen (2020) note the rapid growth of crowdfunding platforms and their ability to connect entrepreneurs, investors, and customers. Rey-Martí et al. (2019) emphasize crowdfunding platforms as a means to legitimize intermediaries promoting social entrepreneurship projects. Chandna (2022) discusses digital platforms for crowdfunding, breaking barriers related to legitimacy issues and the lack of traditional funding sources.

Nevertheless, these platforms are not without criticism. Ahsan (2020) contends that “the sharing economy reflects the intensification of an ongoing neoliberal trend that misuses the concept of entrepreneurship in order to justify certain forms of employment practices, and make a case for regulatory oversight”. Josserand and Kaine (2019) introduce the term ‘sub-entrepreneur’ to describe gig platform workers as a “type of independent contractor who experiences less freedom than those with true entrepreneurial scope and autonomy in their work”. Ravenelle (2017) suggests that gig economy platforms may render entrepreneurs vulnerable.

5.3. Cluster 3: Studies of Collaborative Economy Literature Review

The smallest of the three clusters, Cluster 3, encompasses 13.2% of the active forms and 18.7% of the papers. Dominant terms within this cluster include: (1) review, (2) literature, (3) systematic, (4) analysis, and (5) bibliometric, promoting the designation “studies of collaborative economy literature review”.

Notably, there are relatively few studies that undertake comprehensive reviews of the literature related to CE, many of which are either partial or lack systematic analysis. This underscores the significance of studies like the present one. Saragih (2019), for instance, conducted a systematic literature review on co-creation in the music business, concluding that value co-creation can be harnessed by entrepreneurs to gain monetary, experiential, or social value through virtual and physical co-creative platforms. Shin (2016) proposes a conceptual approach to the relationships between the social economy, social welfare, and social innovation based on a literature review. Braun (2010) conducted a literature review to propose a skilling framework for women entrepreneurs in the knowledge economy, highlighting the need to enhance opportunities for female entrepreneurs in this realm.

Furthermore, some literature reviews have sought to classify studies related to this phenomenon. Silva and Moreira (2022) conducted a bibliometric analysis of entrepreneurship and the gig economy, identifying five main clusters of studies: (1) self-employment and social economy, (2) sharing economy and sustainable development, (3) entrepreneurship and innovation, (4) gig economy and platform economy, and (5) digitalization. Klarin and Suseno (2021) developed a State-of-the-Art review of the sharing economy, categorizing inter-related concepts into four clusters: (1) freelance work and its implications, (2) transportation and solutions for the sustainable development of the sharing economy, (3) user experience and collaborative consumption, and (4) the sharing economy in the context of hospitality and tourism.

6. Conclusions

In the pursuit of a deeper understanding of the entrepreneurial collaborative economy, this research has undertaken a systematic literature review using the PRISMA methodology. Additionally, we have conducted a textometric analysis employing Iramuteq software. This study had two objectives: (1) mapping the literature related to the CE within entrepreneurship with the aim of proposing a research taxonomy, and (2) analyzing unexplored research within this field. The findings confirmed that our chosen methodology has achieved both objectives.

To begin, our investigation has unveiled that the entrepreneurial collaborative economy paradigm remains in a state of emergence within the academic literature. The current research landscape in this area has proven to be somewhat elusive. Through a comprehensive mapping exercise, our results have shed light on this very gap. To be specific, our research on the entrepreneurial collaborative economy has led to its classification into three overarching clusters: (1) innovative ecosystems for value co-creation, (2) sharing economy platforms in entrepreneurial contexts, and (3) studies of collaborative economy literature review.

The first cluster underscores the prevailing perception within the literature that the entrepreneurial collaborative economy functions as an innovative ecosystem, fostering the co-creation of value. Several studies have focused on the role of co-creation as a mechanism for creating new products and services through the collaboration of a wide range of stakeholders. The second cluster highlights the potential of sharing economy platforms as a viable avenue for entrepreneurial activities. These platforms, it appears, present fresh opportunities for entrepreneurs, with existing research emphasizing their pivotal role in promoting collaborative innovations. Finally, the third cluster shows the paucity of studies that have scrutinized the existing literature in this area, thus underscoring the compelling necessity to embark on such investigations.

Turning to our second objective, it is evident that the literature exhibits a noticeable bias towards two specific facets of the CE: (1) collaborative value co-creation and (2) the gig economy. Consequently, scholarly attention has predominantly concentrated on analyzing entrepreneurship activities in these two areas of the CE, while somehow overlooking the remaining five dimensions. Therefore, there is a palpable need for further research delving into the intricate relationships between entrepreneurship and: (1) collaborative consumption, (2) collaborative production, (3) collaborative governance, (4) collaborative finance, and (5) collaborative knowledge. A particularly pressing endeavor would be to dissect the barriers, tensions, and critical success factors within each of these CE movements, as these aspects have been relatively underexplored within the research landscape.

In addition, the overrepresentation of collaborative value co-creation and the gig economy in the literature can be attributed to several factors. First, both areas resonate strongly with dominant research streams in business, management, and innovation studies, where concepts such as customer engagement or co-production are already well-established. Second, the gig economy has received considerable attention from policymakers, media, and the public due to its implications for labor markets, workers’ rights, and regulatory frameworks. Finally, the scalability and global reach of prominent gig and co-creation platforms make them attractive case studies for understanding platform dynamics and user interactions.

In summary, our findings have contributed to a better understanding of the entrepreneurial collaborative economy, a subject that is gradually gaining scholarly attention. It is foreseeable that in the ensuing years, research related to this topic will experience substantial growth. Nevertheless, it is essential to acknowledge that this study is not without its limitations derived from the methodology and technique used. Although we conducted thorough searches for articles in major publishers and databases, others that could have incorporated a greater number of papers into the analysis were excluded. Furthermore, the nature of textometric techniques may have led to the inadvertent exclusion of certain words from our analysis, rendering them unaccounted for. This research, however, has laid the groundwork for a more profound exploration of the entrepreneurial collaborative economy, signifying its growing significance in academia. As we move forward, it is imperative that future studies take into consideration the potential enhancements and refinements of our approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., E.M.G. and M.D.G.; methodology, S.B., M.D.G., E.M.G. and R.M.; software, S.B., E.M.G. and M.D.G.; validation, S.B., M.D.G., E.M.G. and R.M.; formal analysis, S.B. and M.D.G.; investigation, S.B., M.D.G., E.M.G. and R.M.; resources, S.B., M.D.G., E.M.G. and R.M.; data curation, S.B. and E.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B., M.D.G., E.M.G. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, S.B., M.D.G., E.M.G. and R.M.; visualization, S.B.; supervision, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE | Collaborative economy |

References

- Abhari, K., Davidson, E. J., & Xiao, B. (2019). Collaborative innovation in the sharing economy: Profiling social product development actors through classification modeling. Internet Research, 29(5), 1014–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A., Freedman, J., & Prassl, J. (2018). Rethinking legal taxonomies for the gig economy. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 34(3), 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M. (2020). Entrepreneurship and ethics in the sharing economy: A critical perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 161(1), 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, A., Cabral, P., & Casteleyn, S. (2020). Understanding the sharing economy and its implication on sustainability in smart cities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 277, 124077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohammad, M., Farajallah Hosseini, S. J., Mirdamadi, S. M., & Dehyouri, S. (2022). Collaborative networking among agricultural production cooperatives in Iran. Heliyon, 8(11), e11846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal-Chérif, O., Guijarro-Garcia, M., & Ulrich, K. (2022). Fostering sustainable growth in aeronautics: Open social innovation, multifunctional team management, and collaborative governance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansart, S., & Monvoisin, V. (2017). The new monetary and financial initiatives: Finance regaining its position as servant of the economy. Research in International Business and Finance, 39, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S. T. (2023). The sharing economy and collaborative consumption: Strategic issues and global entrepreneurial opportunities. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 21(1), 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaolaza-Llorente, D., Castrillo, J., & Idoiaga-Mondragon, N. (2023). Are women present in history classes? Conceptions of primary and secondary feminist teachers about how to teach women’s history. Women’s Studies International Forum, 98, 102738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, A., Bonhomme, M., Ibáñez, F., & Leyton, J. (2023). The gig economy in Chile: Examining labor conditions and the nature of gig work in a Global South country. Digital Geography and Society, 5, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, E. (2021). Collaborative consumption in the fashion industry: A systematic literature review and conceptual framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 325, 129261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsız, O., & Cifci, I. (2022). Exploring the motives for entrepreneurship in the meal-sharing economy. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(6), 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskas, G., & Raišienė, A. G. (2022). Transition to digital entrepreneurship with a quest of sustainability: Development of a new conceptual framework. Sustainability, 14(3), 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S. J., & Mattsson, J. (2016). Building tribal communities in the collaborative economy: An innovation framework. Prometheus, 34(2), 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S. J., & Mattsson, J. (2017). Understanding collaborative consumption: Test of a theoretical model. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 118, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, J. M., Hochberg, Y. V., & Yi, H. (2022). Launching with a parachute: The gig economy and new business formation. Journal of Financial Economics, 144(1), 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárcena-Ruiz, J. C., & Sagasta, A. (2021). Environmental policies with consumer-friendly firms and cross-ownership. Economic Modelling, 103, 105612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, C., Mistry, I., & Young, N. (2022). Collaborative knowledge mapping to inform environmental policy-making: The case of Canada’s rideau canal national historic site. Environmental Science & Policy, 128, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. (2014). You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J., Miller, A., & Wortmann, K. (2011). Public policies for scaling corporate responsibility standards: Expanding collaborative governance for sustainable development. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 2(2), 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berné-Martínez, J. M., Ortigosa-Blanch, A., & Planells-Artigot, E. (2021). A semantic analysis of crowdfunding in the digital press. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boafo, C., Catanzaro, A., & Dornberger, U. (2022). International entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa: Interfirm coordination and local economy dynamics in the informal economy. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 30(3), 587–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatyreva, K., Verkhovskaya, O., & Makarov, Y. (2021). A springboard for entrepreneurs? Gig and sharing economy and entrepreneurship in Russia. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 15(4), 698–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamigo, A., da Silva, A. A., da Silva, B. P., & Werner, S. M. (2022). Criteria for selecting actors for the value co-creation in startups. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 37(11), 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, N., Bettayeb, B., Sahnoun, M., Yassine, A., & Latreche, A. (2022). Modeling and simulation of human behavior impact on production throughput. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 55(10), 1740–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögenhold, D., Klinglmair, R., & Kandutsch, F. (2017). Solo self-employment, human capital and hybrid labour in the gig economy. Foresight and STI Governance, 11(4), 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, P. (2010). Chapter 3 A skilling framework for women entrepreneurs in the knowledge economy. In P. Wynarczyk, & S. Marlow (Eds.), Contemporary issues in entrepreneurship research (Vol. 1, pp. 35–53). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, S., Bañuls, V. A., & Gallego, M. D. (2021). Is urban resilience a phenomenon on the rise? A systematic literature review for the years 2019 and 2020 using textometry. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 66, 102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Lin, J., & Zhou, Z. (2022). Promoting customer value co-creation through social capital in online brand communities: The mediating role of member inspiration. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, V. (2022). Social entrepreneurship and digital platforms: Crowdfunding in the sharing-economy era. Business Horizons, 65(1), 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X., Mou, J., & Yan, X. (2021). Sharing economy enabled digital platforms for development. Information Technology for Development, 27(4), 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, S. H.-W., Tseng, M.-L., Wu, K.-J., & Cheng, C.-F. (2021). Factors influencing the adoption of sharing economy in B2B context in China: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 175, 105892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbous, A., & Tarhini, A. (2021). Does sharing economy promote sustainable economic development and energy efficiency? Evidence from OECD countries. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 6(1), 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeneve, C., Longhi, J., & Rossy, Q. (2022). Analysing the digital transformation of the market for fake documents using a computational linguistic approach. Forensic Science International: Synergy, 5, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, D. T., & Cortimiglia, M. N. (2017). Value co-creation in web-based multisided platforms: A conceptual framework and implications for business model design. Business Horizons, 60(6), 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, R. P., Lohmann, G., & Oliveira, A. V. M. (2022). A systematic review of the literature on air transport networks (1973–2021). Journal of Air Transport Management, 103, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, V. M., da Costa-Nascimento, D. V., de Sousa Teodósio, A. dos S., & Correia, S. É. N. (2022). Collaborative consumption as sustainable consumption: The effects of Uber’s platform in the context of Brazilian cities. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 5, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rivera, J., Gordo, Á., Cassidy, P., & Apesteguía, A. (2017). A netnographic study of P2P collaborative consumption platforms’ user interface and design. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K., Zhang, Y., Chan, F. T. S., Zhang, C., Lv, J., Liu, Q., Leng, J., & Fu, H. (2021). A cyber-physical production monitoring service system for energy-aware collaborative production monitoring in a smart shop floor. Journal of Cleaner Production, 297, 126599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Méndez, M., & Gummesson, E. (2012). Value co-creation and university teaching quality: Consequences for the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). Journal of Service Management, 23(4), 571–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Yao, X., & Wei, Z. (2023). Research on the process of knowledge value co-creation between manufacturing enterprises and internet enterprises. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 22(3), 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, B., Lüdeke-Freund, F., Hamann, R., & Faccer, K. (2017). Upsides and downsides of the sharing economy: Collaborative consumption business models’ stakeholder value impacts and their relationship to context. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, P. (2011). An approach to quantitatively measuring collaborative performance in online conversations. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ert, E., Fleischer, A., & Magen, N. (2016). Trust and reputation in the sharing economy: The role of personal photos in Airbnb. Tourism Management, 55, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M., & Boily, É. (2019). The rise of the digital economy: Thoughts on blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies for the collaborative economy. International Journal of Innovation Studies, 3(4), 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrer, J. A., & Nenonen, S. (2020). Crowdfunding networks: Structure, dynamics and critical capabilities. Industrial Marketing Management, 88, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felson, M., & Spaeth, J. L. (1978). Community structure and collaborative consumption: A routine activity approach. American Behavioral Scientist, 21(4), 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24(4), 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamalielsson, J., & Lundell, B. (2014). Sustainability of Open Source software communities beyond a fork: How and why has the LibreOffice project evolved? Journal of Systems and Software, 89, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T., Chen, X., Geng, Y., & Yang, K. (2023). Does regional collaborative governance reduce air pollution? Quasi-experimental evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 419, 138283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, L.-M., Newig, J., & Ruf, S. (2023). MSPs for the SDGs—Assessing the collaborative governance architecture of multi-stakeholder partnerships for implementing the sustainable development goals. Earth System Governance, 17, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K., Shankar, K. M., & Kannan, D. (2020). Achieving sustainable development goals through identifying and analyzing barriers to industrial sharing economy: A framework development. International Journal of Production Economics, 227, 107575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., & Michael Hall, C. (2019). Sharing versus collaborative economy: How to align ICT developments and the SDGs in tourism? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(1), 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinevich, V., Huber, F., Karataş-Özkan, M., & Yavuz, Ç. (2019). Green entrepreneurship in the sharing economy: Utilising multiplicity of institutional logics. Small Business Economics, 52(4), 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszka, K. (2017). Framing the collaborative economy—Voices of contestation. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Royo, M. (2023). ‘I prefer to own what I use’: Exploring the role of emotions in upscaling collaborative consumption through libraries in Norway. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 8, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Chen, T., & Wei, Y. (2023). Intrinsic need satisfaction, emotional attachment, and value co-creation behaviors of seniors in using modified mobile government. Cities, 141, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurău, C., & Ranchhod, A. (2020). The sharing economy as a complex dynamic system: Exploring coexisting constituencies, interests and practices. Journal of Cleaner Production, 245, 118799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallem, Y., Ben Arfi, W., & Teulon, F. (2020). Exploring consumer attitudes to online collaborative consumption: A typology of collaborative consumer profiles. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de l’Administration, 37(1), 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2016). The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(9), 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazée, S., Zwienenberg, T. J., Van Vaerenbergh, Y., Faseur, T., Vandenberghe, A., & Keutgens, O. (2020). Why customers and peer service providers do not participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of Service Management, 31(3), 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerwagen, J. H., Kampschroer, K., Powell, K. M., & Loftness, V. (2004). Collaborative knowledge work environments. Building Research & Information, 32(6), 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, K., Morhart, F., Girardin, F., & Hauser, M. (2015). Exploring different types of sharing: A proposed segmentation of the market for “Sharing” businesses. Psychology & Marketing, 32(9), 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, H. O. (1935). A connection between correlation and contingency. Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 31(4), 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, B. (1998). What determines success? Examining the human, financial, and social capital of jamaican microentrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(5), 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., Ouyang, T., Wei, W. X., & Cai, J. (2020). How do manufacturing enterprises construct e-commerce platforms for sustainable development? A case study of resource orchestration. Sustainability, 12(16), 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, E., Kale, A., Akmaz, A., & Çelik, R. (2023). A research to determine the effect of entrepreneurship attitude and education on entrepreneurial intention. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 34(2), 100475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y., Chen, Q., Mu, W., & Zhang, W. (2023). Managing the value Co-creation of peer service providers in the sharing economy: The perspective of customer incivility. Heliyon, 9(6), e16820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W., Zhang, Q., & Luo, J. (2019). Non-collaborative and collaborative financing in a bilateral supply chain with capital constraints. Omega, 88, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.-G., & Mehta, B. (2022). Fostering the inclusion of women as entrepreneurs in the sharing economy through collaboration: A commons approach using the institutional analysis and development framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(3), 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josserand, E., & Kaine, S. (2019). Different directions or the same route? The varied identities of ride-share drivers. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(4), 549–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali Saraji, M., & Streimikiene, D. (2023). Challenges to the low carbon energy transition: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Energy Strategy Reviews, 49, 101163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M., & Read, S. (2021). Co-creative entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(4), 106125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, A., & Suseno, Y. (2021). A state-of-the-art review of the sharing economy: Scientometric mapping of the scholarship. Journal of Business Research, 126, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, S., Jasrotia, S. S., & Mishra, H. G. (2022). Value co-creation in sharing economy: Indian experience. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 13(1), 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakkonen, A., Hujala, T., & Pykäläinen, J. (2019). Integrating intangible resources enables creating new types of forest services—Developing forest leasing value network in Finland. Forest Policy and Economics, 99, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-Y., Grinevich, V., & Chipulu, M. (2023). How can value co-creation be integrated into a customer experience evaluation? European Management Journal, 41(4), 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leick, B., Falk, M. T., Eklund, M. A., & Vinogradov, E. (2022). Individual-contextual determinants of entrepreneurial service provision in the platform-based collaborative economy. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 28(4), 853–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveldt, H. (2023). Food industry influence in collaborative governance: The case of the Dutch prevention agreement on overweight. Food Policy, 114, 102380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., & Tuunanen, T. (2022). Information Technology–Supported value Co-Creation and Co-Destruction via social interaction and resource integration in service systems. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 31(2), 101719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P. M. C., Au, W. C., Leung, V. T. Y., & Peng, K.-L. (2020). Exploring the meaning of work within the sharing economy: A case of food-delivery workers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, J. H., Corcoran, J., & Pillai, V. (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, X., Zhu, Z., & Liang, J. (2022). The evolution game analysis of platform ecological collaborative governance considering collaborative cultural context. Sustainability, 14(22), 14935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, P., Kamble, S., Belhadi, A., Mani, V., & Pundir, A. (2022). Digital twin implementation for performance improvement in process industries—A case study of food processing company. International Journal of Production Research, 61(23), 8343–8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A. A., & Brem, A. (2021). Digital twins for collaborative robots: A case study in human-robot interaction. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 68, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marpsat, M. (2010). La méthode Alceste. Sociologie, 1(1), N°1. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/sociologie/312 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Massi, M., Rod, M., & Corsaro, D. (2020). Is co-created value the only legitimate value? An institutional-theory perspective on business interaction in B2B-marketing systems. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 36(2), 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A. M., Tonin, F. S., Buzzi, M. F., Pontarolo, R., & Fernandez-Llimos, F. (2019). Mapping pharmacy journals: A lexicographic analysis. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15(12), 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menéndez-Caravaca, E., Bueno, S., & Gallego, M. D. (2021). Exploring the link between free and open source software and the collaborative economy: A Delphi-based scenario for the year 2025. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, M. S. B., & Enu-Kwesi, F. (2018). Research collaboration for a knowledge-based economy: Towards a conceptual framework. Triple Helix, 5(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, A. L., Ramos, C., & Bortoluzzo, A. B. (2021). Sharing economy versus collaborative consumption: What drives consumers in the new forms of exchange? Journal of Business Research, 128, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery, 8(5), 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondragon, N. I., Munitis, A. E., & Txertudi, M. B. (2022). The breaking of secrecy: Analysis of the hashtag #MeTooInceste regarding testimonies of sexual incest abuse in childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 123, 105412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mont, O., Palgan, Y. V., Bradley, K., & Zvolska, L. (2020). A decade of the sharing economy: Concepts, users, business and governance perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 269, 122215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraux, F., Phan, D. A., & Vo, T. L. H. (2023). Collaborative financing and supply chain coordination for corporate social responsibility. Economic Modelling, 121, 106198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouazen, A. M., & Hernández-Lara, A. B. (2023). Entrepreneurial ecosystem, gig economy practices and Women’s entrepreneurship: The case of Lebanon. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 15(3), 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, W., Tan, T. M., Tajvidi, M., & Hajli, N. (2021). How do experiences enhance brand relationship performance and value co-creation in social commerce? The role of consumer engagement and self brand-connection. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 171, 120952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera-Sánchez, J.-J., Martinez-Cañas, R., García-Haro, M.-Á., & Martínez-Ruiz, M. P. (2022). Exploring the knowledge structure of the relationship between value co-creation and customer satisfaction. Management Decision, 60(12), 3366–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, A., & Yashaiya, N. H. (2019). Examining the collaborative process: Collaborative governance in Malaysia. Halduskultuur, 20(1), 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostertag, F., Hahn, R., & Ince, I. (2021). Blended value co-creation: A qualitative investigation of relationship designs of social enterprises. Journal of Business Research, 129, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palátová, P., Rinn, R., Machoň, M., Paluš, H., Purwestri, R. C., & Jarský, V. (2023). Sharing economy in the forestry sector: Opportunities and barriers. Forest Policy and Economics, 154, 103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliokaitė, A., & Sadauskaitė, A. (2023). Institutionalisation of participative and collaborative governance: Case studies of Lithuania 2030 and Finland 2030. Futures, 150, 103174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panic, N., Leoncini, E., de Belvis, G., Ricciardi, W., & Boccia, S. (2013). Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE, 8(12), e83138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjwani, A., & Xiong, H. (2023). The causes and consequences of medical crowdfunding. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 205, 648–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, E., Albinsson, P. A., Ozanne, L. K., Marine-Roig, E., & Perera, B. Y. (2022). Editorial: Can the sharing economy contribute to wellbeing? Exploring the impact of the sharing economy on individual and collective wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1030430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parums, D. V. (2021). Editorial: Review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, and the updated preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 27, e934475-1–e934475-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J. A., Fritz, D. A., & Davis, P. S. (2010). Entrepreneurial orientation and the performance of religious congregations as predicted by rational choice theory. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(1), 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E. R. G., & Netter, S. (2015). Collaborative consumption: Business model opportunities and barriers for fashion libraries. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 19(3), 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, B., Pinto, R., Melo, M., Cabral, L., & Bessa, M. (2021). Immersive virtual reality for foreign language education: A PRISMA systematic review. IEEE Access, 9, 48952–48962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, B. Y., Albinsson, P. A., Nafees, L., & Matthews, L. (2023). Collaborative consumption participation intentions: A cross-cultural study of Indian and U.S. consumers. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 33(1), 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouri, M. J., & Hilty, L. M. (2021). The digital sharing economy: A confluence of technical and social sharing. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 38, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) and social value co-creation. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 42(3/4), 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenelle, A. J. (2017). Sharing economy workers: Selling, not sharing. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(2), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenelle, A. J. (2019). We’re not uber: Control, autonomy, and entrepreneurship in the gig economy. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 34(4), 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, M. (1990). Alceste une méthodologie d’analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurelia de gerard de nerval. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, 26(1), 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.-S., Ma, C.-Q., Chen, X.-Q., Lei, Y.-T., & Wang, Y.-R. (2023). Sustainable finance and blockchain: A systematic review and research agenda. Research in International Business and Finance, 64, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, M. L., Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A. P., Moher, D., Page, M. J., Koffel, J. B., Blunt, H., Brigham, T., Chang, S., Clark, J., Conway, A., Couban, R., de Kock, S., Farrah, K., Fehrmann, P., Foster, M., Fowler, S. A., Glanville, J., & PRISMA-S Group. (2021). PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Martí, A., Mohedano-Suanes, A., & Simón-Moya, V. (2019). Crowdfunding and social entrepreneurship: Spotlight on intermediaries. Sustainability, 11(4), 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T. H. (2016). The sharing economy: Business cases of social enterprises using collaborative networks. Procedia Computer Science, 91, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahut, J.-M., Iandoli, L., & Teulon, F. (2021). The age of digital entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 56(3), 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh Al-Omoush, K., Orero-Blat, M., & Ribeiro-Soriano, D. (2021). The role of sense of community in harnessing the wisdom of crowds and creating collaborative knowledge during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Research, 132, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salviati, M. E. (2017). Manual do Aplicativo Iramuteq (versão 0.7 Alpha 2 e R Versão 3.2.3). Available online: http://www.iramuteq.org/documentation/fichiers/manual-do-aplicativo-iramuteq-par-maria-elisabeth-salviati (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Saragih, H. (2019). Co-creation experiences in the music business: A systematic literature review. Journal of Management Development, 38(6), 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswati, A., Said, A., Nuh, M., & Setyowati, E. (2023). Tourism economy in collaborative governance perspective. International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(6), e01978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis-Onofre, R., Catalá-López, F., Aromataris, E., & Lockwood, C. (2021). How to properly use the PRISMA statement. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, H., Araz, C., & Ozkarahan, I. (2008). Collaborative production–distribution planning in supply chain: A fuzzy goal programming approach. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 44(3), 396–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S. M. R., & Kaufmann, H. R. (2016). Entrepreneurial co-creation: A research vision to be materialised. Management Decision, 54(6), 1250–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S., Cheng, S., & Jia, R. (2023). Can low carbon policies achieve collaborative governance of air pollution? Evidence from China’s carbon emissions trading scheme pilot policy. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 103, 107286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C. (2016). A conceptual approach to the relationships between the social economy, social welfare, and social innovation. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 7(2), 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B. C., & Moreira, A. C. (2022). Entrepreneurship and the gig economy: A bibliometric analysis. Cuadernos de Gestión, 22(2), 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, C., La Sala, A., & Montella, M. M. (2017). The rise of P2P ecosystem: A service logics amplifier for value co-creation. The TQM Journal, 29(6), 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J., Gao, Y., Huang, Y., & Chen, L. (2023). Being friendly and competent: Service robots’ proactive behavior facilitates customer value co-creation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 196, 122861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, Y. S. O. (2021). O Uso do software Iramuteq: Fundamentos de lexicometria para pesquisas qualitativas. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, 21(4), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Cheng, X., Hua, Y., & Zhang, W. (2021). What leads to value co-creation in reward-based crowdfunding? A person-environment fit perspective. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 149, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. (2015). Facilitating generation of local knowledge using a collaborative initiator: A NIMBY case in Guangzhou, China. Habitat International, 46, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist-Andberg, H., & Åkerman, M. (2022). Collaborative governance as a means of navigating the uncertainties of sustainability transformations: The case of Finnish food packaging. Ecological Economics, 197, 107455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J. S., & Chen, W. (2022). Peer feedback to support collaborative knowledge improvement: What kind of feedback feed-forward? Computers & Education, 187, 104467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, P., Star, C., Sutton, Z., & Clarke, B. (2023). Navigating collaborative governance: Network ignorance and the performative planning of South Australia’s emergency management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 96, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, H. C. (2024). Business model change and internationalization in the sharing economy. Journal of Business Research, 170, 114250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X., Song, Y., Luo, C., Zhou, X., & Lev, B. (2021). Herding behavior in supplier innovation crowdfunding: Evidence from Kickstarter. International Journal of Production Economics, 239, 108184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiglao, N. C. C., Ng, A. C. L., Tacderas, M. A. Y., & Tolentino, N. J. Y. (2023). Crowdsourcing, digital co-production and collaborative governance for modernizing local public transport services: The exemplar of General Santos City, Philippines. Research in Transportation Economics, 100, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, M., Renzi, M. F., & Mattia, G. (2018). Understanding the link between collaborative economy and sustainable behaviour: An empirical investigation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 4467–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L. T. (2017). Under entrepreneurial orientation, how does logistics performance activate customer value co-creation behavior? The International Journal of Logistics Management, 28(2), 600–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Juárez, L. E., Gallardo-Vázquez, D., & Ramos-Escobar, E. A. (2021). Online buyers and open innovation: Security, experience, and satisfaction. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]