Measuring the Digital Economy in Kazakhstan: From Global Indices to a Contextual Composite Index (IDED)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Transformation in Emerging Economies

2.2. Limitations of Global Indices in Capturing Context

- Reliance on Obsolete Infrastructure Indicators

- 2.

- Lack of Regional and Sectoral Granularity

- 3.

- Neglect of Qualitative and Behavioral Dimensions

- 4.

- Limited Consideration of Institutional and Regulatory Readiness

- 5.

- Methodological Inflexibility and Lack of Local Calibration

- 6.

- Under-representation of Cybersecurity and Risk Management

2.3. Kazakhstan-Specific Challenges and the Need for Contextualization

2.4. Towards a Contextual Index: Rationale and Conceptual Framework for IDED

- -

- ICT infrastructure: This pillar includes indicators such as broadband coverage, average internet speed, and access to digital devices. These reflect the foundational technological environment required for digital participation and are further contextualized to account for regional disparities and service quality.

- -

- Human capital and digital literacy: Indicators in this pillar assess digital skills, educational attainment in ICT-related fields, and workforce readiness for digital transformation. The emphasis extends beyond formal education to include lifelong learning and the adaptability of human resources to emerging technologies.

- -

- Economic digitization: This dimension focuses on SME digital adoption, e-commerce penetration, and innovation output. It captures the extent to which businesses integrate digital tools into their operations and contribute to the creation of digital value.

- -

- Digital public services: This pillar includes the availability and interoperability of e-government services, the level of automation, and citizen satisfaction with online platforms. Unlike global indices, the IDED also evaluates the degree to which AI and big data technologies are embedded in public administration, reflecting more advanced stages of digital government transformation.

- -

- Cybersecurity and institutional trust: This pillar conceptualizes cybersecurity as the ability of public and private actors to protect systems, data, and infrastructure from cyber threats. Indicators include the presence of legal frameworks, business cyber preparedness, and incident response capacity. Digital trust is defined as users’ perceived reliability, integrity, and safety of digital systems, and is influenced by factors such as policy transparency, data protection, legal enforcement, and the consistency of public service delivery (Kalinin, 2024; Brici & Achim, 2023).

3. Methodology

3.1. Analytical Framework and Data Sources

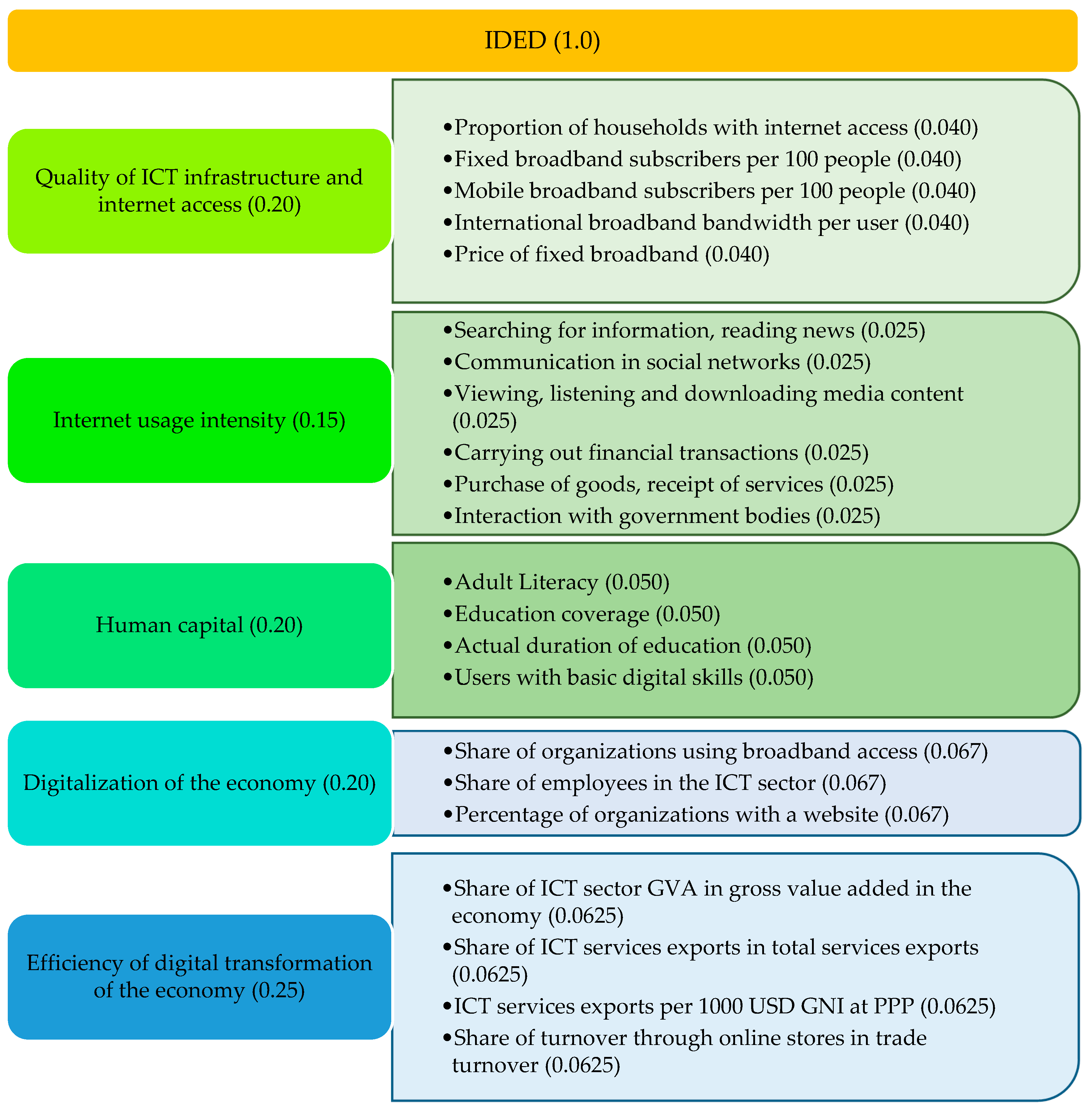

3.2. Design and Construction of the IDED Index

3.3. Empirical Survey and Statistical Validation

- Demographic audience: Includes people aged 20 to 60 years, without division by gender, nationality, education, and other demographic characteristics;

- Consumer audience: Includes customers or potential customers who use Internet resources and digital technologies;

- Geographic audience: Includes people living in the East Kazakhstan region.

- Descriptive statistical analysis: The frequency distribution, arithmetic mean, variance, and standard deviation were calculated for each survey item to evaluate response patterns.

- Correlation analysis: Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were used to determine the strength and direction of relationships between proposed indicators (e.g., cybersecurity) and composite digital development scores.

- Regression modelling: To further substantiate the inclusion of new indicators, such as cybersecurity, in the measurement of digital economy development, linear regression models were estimated for selected countries (Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark). In these models, the DESI index served as the dependent variable and the national level of cybersecurity as the independent variable.

4. Results

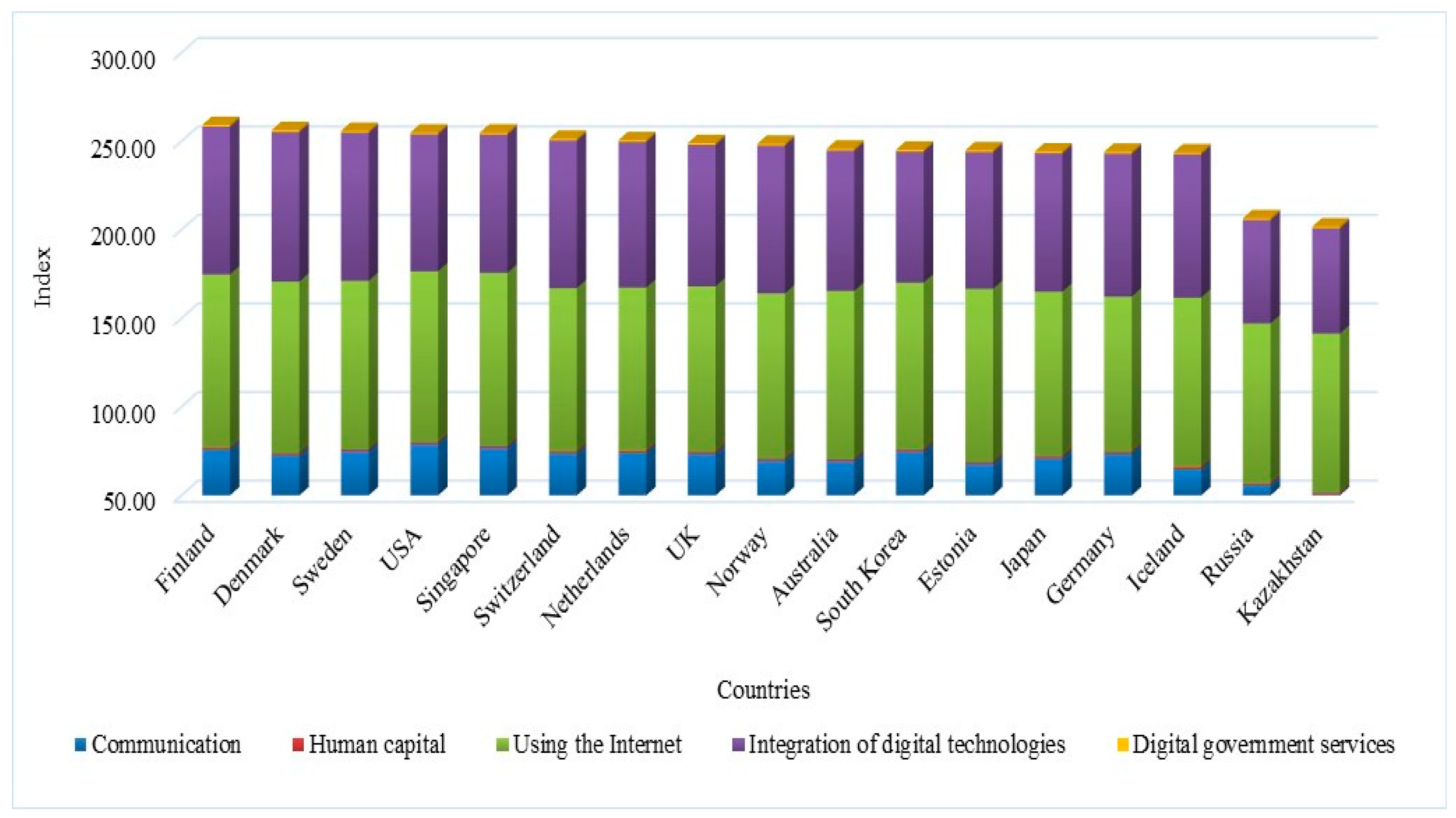

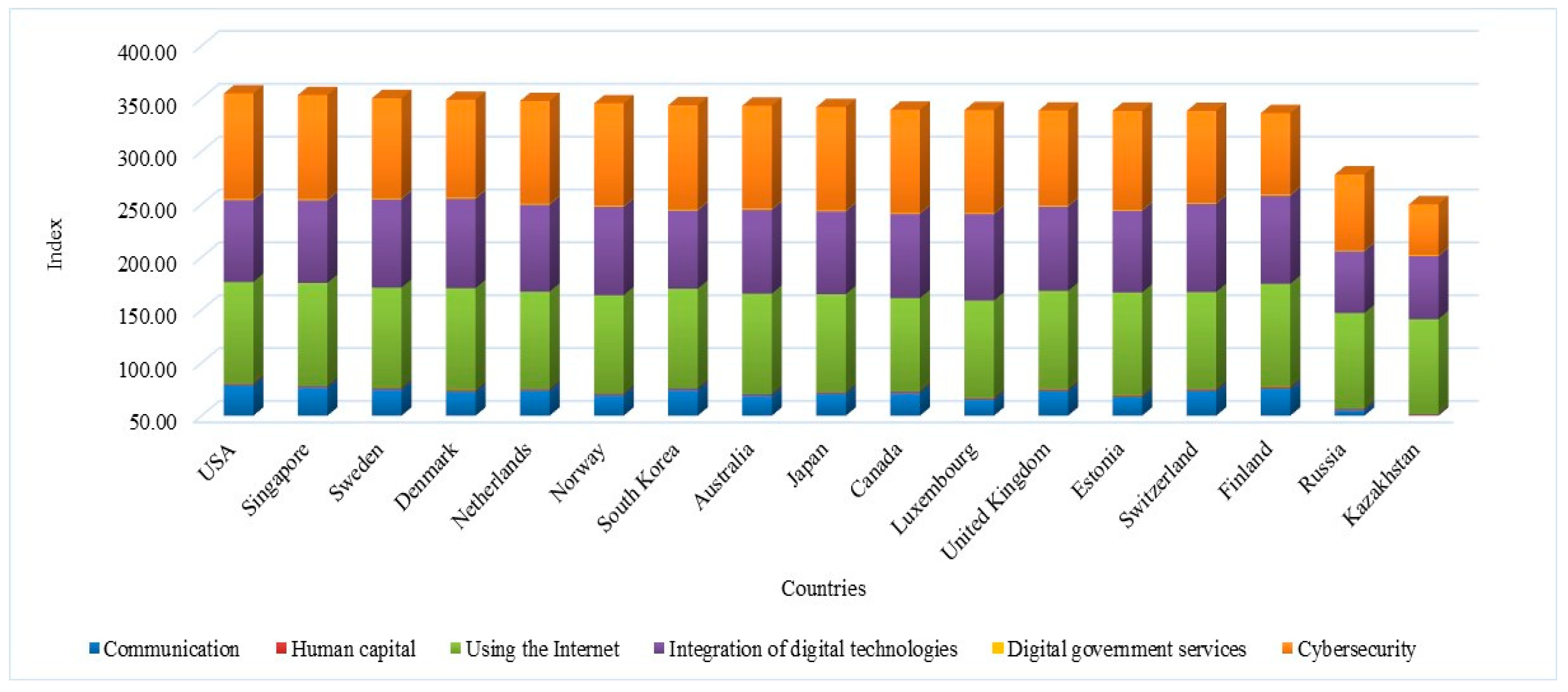

4.1. Kazakhstan’s Position in International Digital Economy Indices

- Group 1—The “leading” countries, with a composite DESI index of over 17;

- Group 2—The “developing” countries, with a composite DESI index of over 10;

- Group 3—The “lagging” countries, with a composite DESI index of under 10.

4.2. Index of Digital Economy Development (IDED)

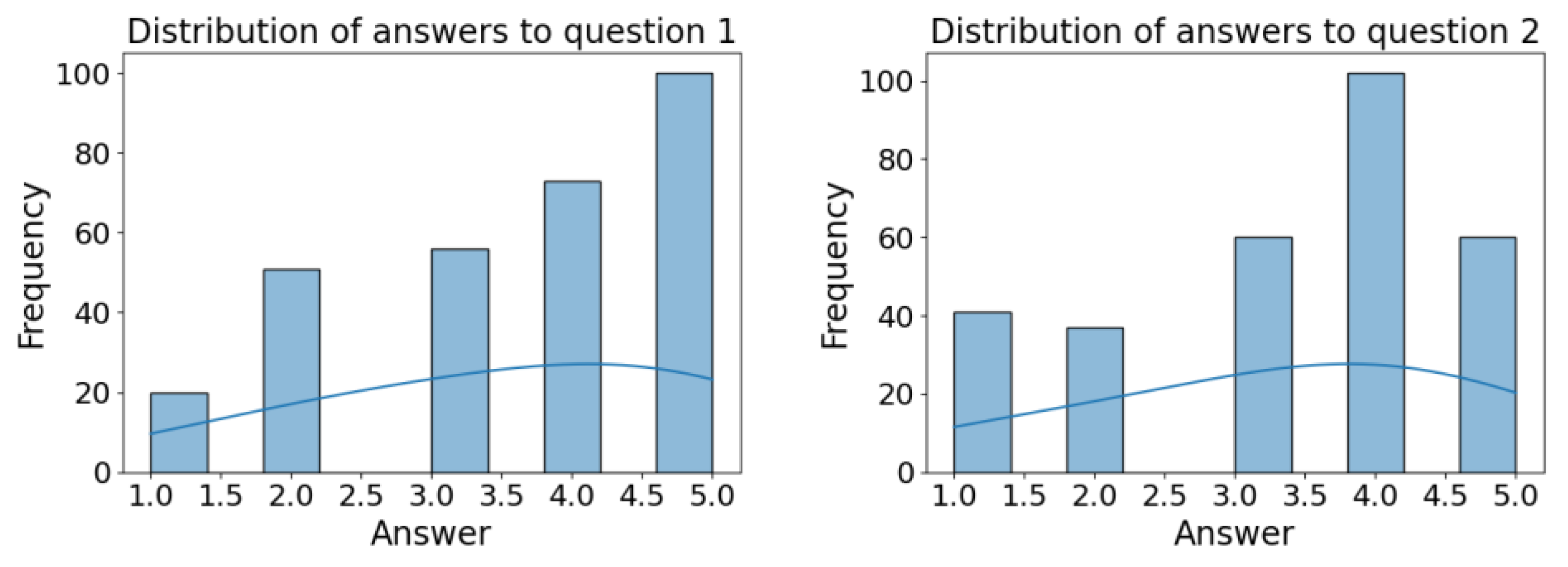

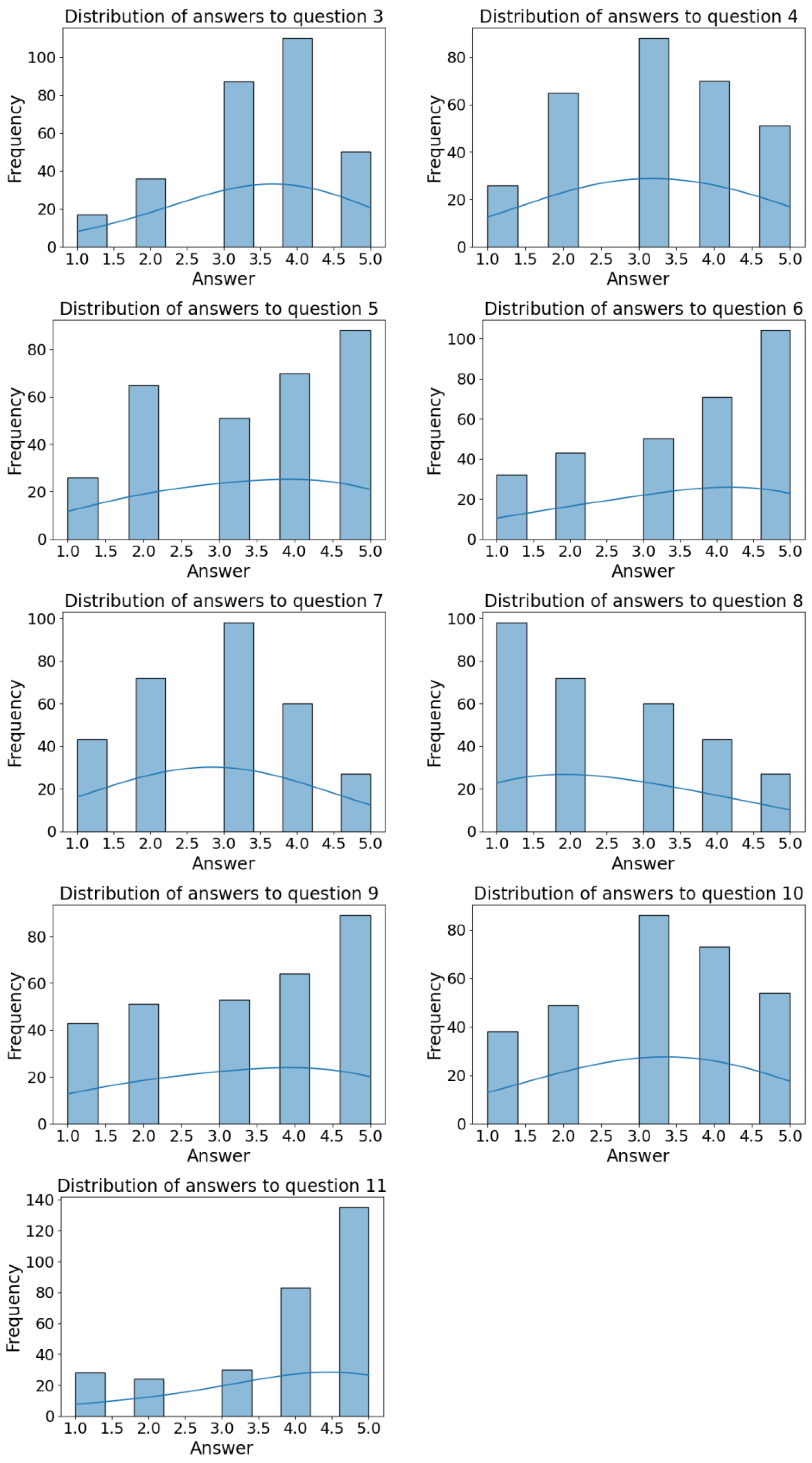

4.3. Survey Results and Statistical Analysis

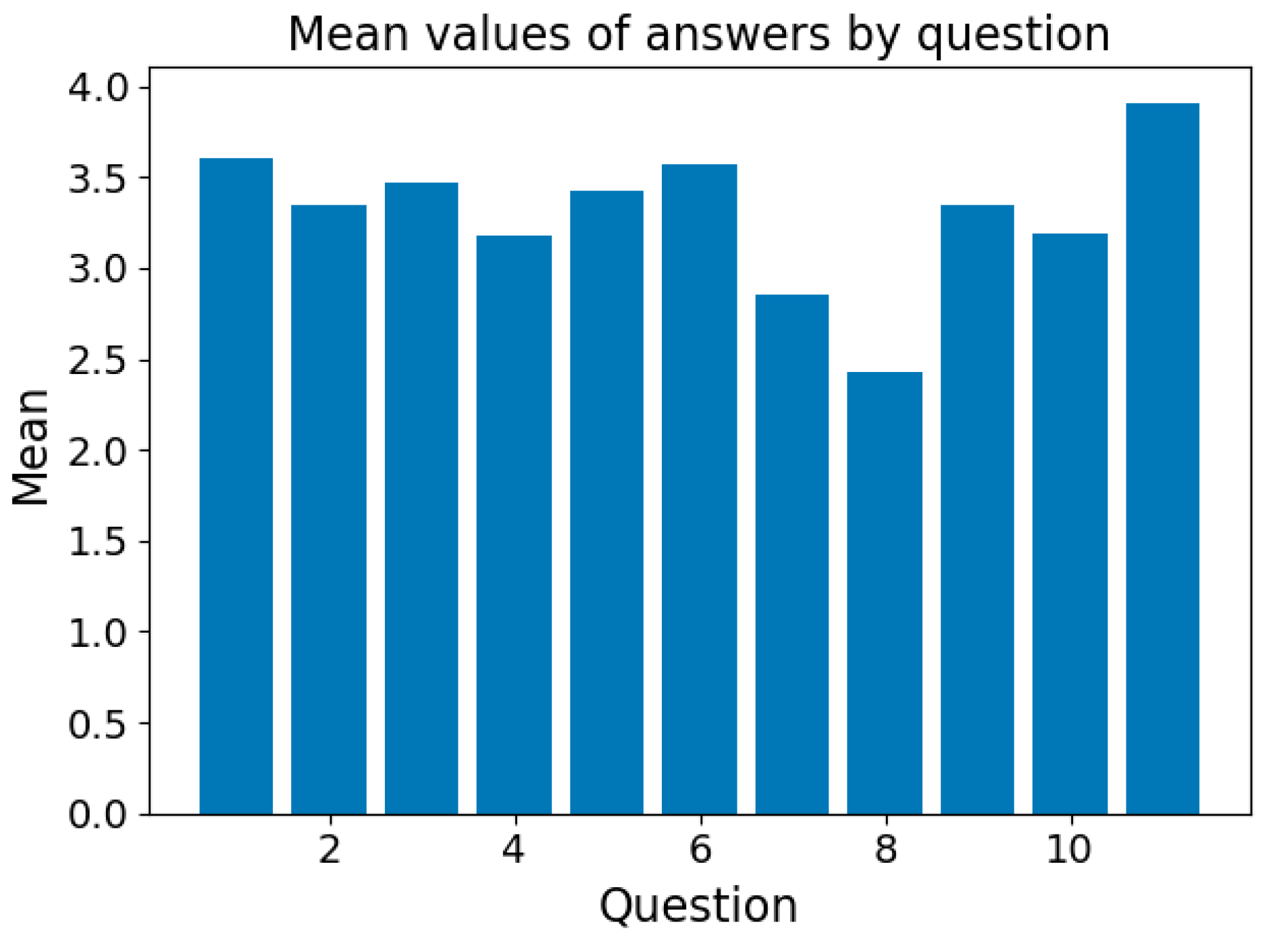

- The highest mean value was recorded for Question 11 (Cybersecurity), with a mean of 3.91, indicating high agreement and perceived importance;

- The lowest mean value was for Question 8 (Integration of digital technologies into business), at 2.43, suggesting dissatisfaction or skepticism regarding this domain;

- Question 9 (Digital public services) exhibited the highest variance (2.02) and standard deviation (1.42), implying wide variation in public opinions;

- The lowest variance (1.16) and standard deviation (1.08) were observed for Question 3 (Revision of sub-indices), indicating consistency in responses.

4.4. Regression Analysis of Cybersecurity and DESI

- H0 (null hypothesis): The cybersecurity indicator does not have a statistically significant impact on the DESI index;

- H1 (alternative hypothesis): The cybersecurity indicator has a statistically significant impact on the DESI index.

- The Netherlands: r = 0.8416;

- Sweden: r = 0.9522;

- Denmark: r = 0.7405.

- Regression equation: y = 29.31 + 27.47x;

- Coefficient of determination: R2 = 0.70;

- p-value of β: <0.05.

- Regression equation: y = 22.58 + 40.12x;

- Coefficient of determination: R2 = 0.90;

- p-value of β: <0.05.

- Regression equation: y = 35.27 + 21.43x;

- Coefficient of determination: R2 = 0.55;

- p-value of β: <0.05.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alimbaev, A., Bitenova, B., & Bayandin, M. (2021). Information and communication technologies in the healthcare system of the republic of Kazakhstan: Economic efficiency and development prospects. Montenegrin Journal of Economics, 17(3), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anatan, L., & Nur. (2023). Micro, small, and medium enterprises’ readiness for digital transformation in Indonesia. Economies, 11(6), 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston Consulting Group. (2024). e-Intensity index. Available online: https://media-publications.bcg.com/HTML5Interactives/e-intensity/index.html (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Brici, I., & Achim, M. V. (2023). Does the digitalization of public services influence economic and financial crime? Studies in Business and Economics, 18(2), 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Xu, S., Lyulyov, O., & Pimonenko, T. (2023). China’s digital economy development: Incentives and challenges. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 29(2), 518–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development of the Digital Economy of Kazakhstan. (2025). Post-soviet issues. Available online: https://www.postsovietarea.com/jour/article/view/270 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Digital Progress and Trends Report 2023. (n.d.). World Bank. [CrossRef]

- Dinh, K. C., Ngo, T. Q., & Nguyen, D. V. (2023). Firm-level digital technology and Total Factor Productivity in a developing country: Evidence from panel data in Vietnam. Cuadernos de Economia-Spain, 46(130), 41–55. Available online: https://cude.es/submit-a-manuscript/index.php/CUDE/article/view/348 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- European Commission. (2024). The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI)|shaping Europe’s digital future. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Fletcher School, Tufts University. (2024). Digital evolution index: Trajectory. Available online: https://digitalevolutionindex.tufts.edu/trajectory (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Gartner. (n.d.). Top cybersecurity trends and strategies for securing the future. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/cybersecurity/topics/cybersecurity-trends (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Gertzen, W. M., Van der Lingen, E., & Steyn, H. (2022). Goals and benefits of digital transformation projects: Insights into project selection criteria. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 25(1), a4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska-Majkowska, H., Komor, A., Pilewicz, T., & Zarebski, P. (2023). The regional environment of smart organisations as a source for entrepreneurship development in the EU. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 11(3), 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloshchapova, T., Yamashev, V., Skornichenko, N., & Strielkowski, W. (2023). E-government as a Key to the economic prosperity and sustainable development in the post-COVID era. Economies, 11(4), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R., Erasmo Gomez-Morantes, J., Graham, M., Howson, K., Mungai, P., Nicholson, B., & Van Belle, J.-P. (2021). Digital platforms and institutional voids in developing countries: The case of ride-hailing markets. World Development, 145, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huawei. (2024). Global digital index. Available online: https://www.huawei.com/en/gdi (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Hung, N. T. (2023). The effects of digitalization, energy intensity, and the demographic dividend on Viet Nam’s economic sustainability goals. Asian Development Review, 40(2), 399–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMD World Competitiveness Center. (2024). World digital competitiveness ranking. Available online: https://www.imd.org/centers/wcc/world-competitiveness-center/rankings/world-digital-competitiveness-ranking/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Intalar, N., Ueki, Y., & Jeenanunta, C. (2024). Enhancing competitiveness: Driving and facilitating factors for Industry 4.0 adoption in Thai manufacturing. Economies, 12(8), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union. (2024). ICT development index (IDI). Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/IDI/default.aspx (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Jankowska, B., & Gotz, M. (2024). Attracting and hosting foreign direct investment in digital transformation time. The case of post-transition economies. Ekonomista, 2, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinin, O. (2024). Investment security in the development of the digital economy. Economics Ecology Socium, 8(2), 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalu, K., & Ibrahim, W. H. B. W. (2024). Does the digitalization crusade a way out of poverty and income inequality? Evidence from developing countries. International Journal of Social Economics, 51(12), 1662–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacuka, M., Myovella, G., & Haucap, J. (2024). Productivity paradox in Africa: Does Digitalization foster labor productivity in African economies? Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 16(2), 8374–8393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D. M. H., Cordova, M., & Khin, S. (2025). The key enablers of SMEs readiness in Industry 4.0: A case of Malaysia. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 20(3), 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruss, G., Petersen, I., Sanni, M., Adeyeye, D., & Egbetokun, A. (2025). Do we measure what should be measured? Towards a research and theoretical agenda for STI measurement in Africa. Innovation and Development, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuanaliyev, A., Taubayev, A., Kunyazov, Y., Ernazarov, T., Mussipova, L., & Saduakassova, A. (2024). Digital and economic transformation in the public administration system. Montenegrin Journal of Economics, 20(3), 63–78. Available online: https://mnje.com/sites/mnje.com/files/v20n3/063-078%20%20-%20Kuanaliyev%20et%20al.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Kulzhambekova, B., Tashenova, L., & Mamrayeva, D. (2023). Theoretical and practical approach to the essential characteristics and structure of digital ecosystems of industrial enterprises. Economic Annals-XXI, 205(9–10), 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Han, Q., & Lu, H. (2024). Can information construction promote the digital transformation of enterprises? Evidence from the “Pilot Zone for the Integration of Informatization and Industrialization”. Economic Change and Restructuring, 57(3), 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., & Kharchenko, T. (2023). Innovations in the field of sports industry management: Assessment of the digital economy’s impact on the qualitative development of the sports industry. Baltic Journal of Economic Studies, 9(3), 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhno, I., Koval, V., Sedikova, I., & Kotlubai, V. (2022). Digital globalization in the international development of strategic alliances. Economics Ecology Socium, 6(1), 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M., Ali, Y., Rehman, O. U., & Saarinen, L. T. (2024). Barriers and strategies for digitalisation of economy in developing countries: Pakistan, a case in point. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(1), 4730–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassir, S., Lebdaoui, I., Chetioui, Y., & Lebdaoui, H. (2023). Factors influencing SMEs’ intention to adopt electronic tendering: Empirical evidence from an emerging African market. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkwei, E. S., Rambe, P., & Simba, A. (2023). Entrepreneurial intention: The role of the perceived benefits of digital technology. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 26(1), a4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). Improving framework conditions for the digital transformation of businesses in Kazakhstan. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otarbayeva, A. B., Arupov, A. A., Abaidullayeva, M. M., Dadabayeva, D. M., & Khajiyeva, G. U. (2024). Investment cooperation as a digital economy development method for the Republic of Kazakhstan and the EU. World Development Perspectives, 36, 100636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovski, I., Fedajev, A., & Mihajlovic, I. (2024). Technology-based factors of globalization in market and transition economies. Is there a difference? Business Management and Economics Engineering, 22(1), 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portulans Institute. (2024). The network readiness index (NRI). Available online: https://networkreadinessindex.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- PwC. (2025, January 16). 2025 global digital trust insights report. Available online: https://library.cyentia.com/report/report_024530.html (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Sembekov, A., Tazhbayev, N., Ulakov, N., Tatiyeva, G., & Budeshov, Y. (2021). Digital modernization of Kazakhstan’s economy in the context of global trends. Economic Annals-XXI, 187(1–2), 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, J. J., Marjanovic, I., Drezgic, S., & Popovic, Z. (2021). The digital competitiveness of European countries: A multiple-criteria approach. Journal of Competitiveness, 13(2), 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultanova, G., & Naser, H. (2024). The impact of information and communication technologies on export diversification: Evidence from developing countries. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazhiyev, R. O., Dirsehan, T., Baimukhanbetova, E. E., & Sandykbaeva, U. D. (2024). Road freight quality management in industry 4.0: International experience and perspectives in Kazakhstan. Economies, 12(8), 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokmergenova, M., Banhidi, Z., & Dobos, I. (2021). Analysis of I-DESI dimensions of the digital economy development of the Russian Federation and EU-28 using multivariate statistics. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo Universiteta-Ekonomika-St Petersburg University Journal of Economic Studies, 37(2), 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsapova, O., Zhailaubayeva, S., Kendyukh, Y., Smolyaninova, S., & Abdulova, O. (2024). Industry specifics and problems of digitalization in the agro-industrial complex of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 16, 9492–9511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ualtayev, M. D., Ualtayeva, A. S., Kaliyeva, S. A., & Vasa, L. (2024, September 1). Problems and prospects for legal regulation of innovations in digital and information technologies of the labour market in Kazakhstan.|ebscohost. Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/contentitem/gcd:181126100?sid=ebsco:plink:crawler&id=ebsco:gcd:181126100 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2024a). E-government development index (EGDI): Kazakhstan. Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Data/Country-Information/id/87-Kazakhstan (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2024b). E-participation index (EPI). Available online: https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/About/Overview/E-Participation-Index (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme. (2024). Human development index (HDI). Human development reports. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Van, B. N. (2021). The digitalization—Economic growth relationship in developing countries and the role of governance. Scientific Annals of Economics and Business, 68(4), 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vovk, V., Denysova, A., Rudoi, K., & Kyrychenko, T. (2021). Management and legal aspects of the symbiosis of banking institutions and fintech companies in the credit services market in the context of digitization. Estudios de Economia Aplicada, 39(7), e5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2024). Overview. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/digital/overview (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- World Economic Forum. (n.d.). Global cybersecurity outlook 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-cybersecurity-outlook-2025/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). (2024). Global innovation index 2024. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/web-publications/global-innovation-index-2024/en/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Yang, L., & Lin, Z. (2024). Opportunity or risk? Mobile phones and the social inclusion gap among people with visual impairments. In Disability and society (Vol. 39, Issue 1, pp. 126–144). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., Zhu, C., & Yang, Y. (2024). Does urban digital construction promote economic growth? Evidence from China. Economies, 12(3), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Y. (2021). Transition to the digital economy, its measurement and the relationship between digitalization and productivity. Istanbul Iktisat Dergisi-Istanbul Journal of Economics, 71(1), 283–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., & Cao, J. (2024). Measurement of coupling development level of new infrastructure investment and digital transformation and its temporal and spatial evolution trend. arXiv, arXiv:2412.19861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Conceptual Framework | Hierarchical model comprising three tiers: (1) readiness to implement digital technologies, (2) intensity of usage, and (3) impact on national development. |

| Sub-Indices | Five key sub-indices: (1) ICT infrastructure and access, (2) internet usage, (3) human capital, (4) economic digitalization, and (5) effectiveness of digital transformation. |

| Data Sources | Primary and secondary data from international (ITU, World Bank, UNDP) and national (KazStat) sources. |

| Normalization | Min–max scaling method applied to ensure comparability across indicators with different units. |

| Weighting Scheme | Linear weighted aggregation. Weights range from 15% to 25%, assigned based on thematic relevance and expert consultation. |

| Calculation Procedure | Step 1: Justification of indicator structure. Step 2: Data collection. Step 3: Indicator normalization. Step 4: Weighting and aggregation. Step 5: Scoring. |

| Outcome | Composite IDED score capturing readiness, usage, and macroeconomic impact. Enables cross-country comparison and internal policy diagnostics. |

| Rank | State | Composite Index (I-DESI) | Communication | Human Capital | Using the Internet | Integration of Digital Technologies | Digital Government Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Finland | 51.846 | 75.76 | 0.942 | 98.10 | 83.47 | 0.958 |

| 2 | Denmark | 51.257 | 72.70 | 0.952 | 97.10 | 84.55 | 0.985 |

| 3 | Sweden | 51.169 | 74.99 | 0.952 | 95.30 | 83.67 | 0.933 |

| 4 | United States of America | 50.989 | 78.96 | 0.927 | 96.70 | 77.44 | 0.920 |

| 5 | Singapore | 50.974 | 76.94 | 0.949 | 97.80 | 78.21 | 0.969 |

| 6 | Switzerland | 50.279 | 73.71 | 0.967 | 92.40 | 83.42 | 0.900 |

| 7 | Netherlands | 50.132 | 73.94 | 0.946 | 92.50 | 82.32 | 0.954 |

| 8 | UK | 49.804 | 73.57 | 0.940 | 93.60 | 79.95 | 0.958 |

| 9 | Norway | 49.718 | 69.7 | 0.966 | 93.40 | 83.59 | 0.932 |

| 10 | Australia | 49.159 | 69.43 | 0.946 | 95.10 | 79.36 | 0.958 |

| 11 | South Korea | 49.043 | 74.85 | 0.929 | 94.40 | 74.07 | 0.968 |

| 12 | Estonia | 48.986 | 67.85 | 0.899 | 97.90 | 77.31 | 0.973 |

| 13 | Japan | 48.847 | 70.96 | 0.920 | 93.20 | 78.22 | 0.935 |

| 14 | Germany | 48.808 | 73.54 | 0.950 | 87.80 | 80.81 | 0.938 |

| 15 | Iceland | 48.741 | 64.86 | 0.959 | 95.90 | 81.02 | 0.967 |

| 16 | Russia | 41.303 | 55.74 | 0.821 | 90.60 | 58.50 | 0.853 |

| 17 | Kazakhstan | 40.371 | 50.52 | 0.802 | 90.10 | 59.53 | 0.901 |

| Indicators | WDCI | DEI | DESI | e-Intensity | IDI | NRI | EGDI | EPART | GCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional Environment Assessment | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + |

| Innovative Environment Level Assessment | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + |

| Development of Telecommunications Infrastructure | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Availability of ICT Services at a Price | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| Education Level of the Population | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | |

| Development of Practical Skills in Using ICT | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Directions of Internet Use by the Population | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | - |

| Use of Digital Technologies in Business | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | - | + |

| Access to State Electronic Services | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + |

| Assessment of Information Security | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Development of the ICT Sector | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| Level of International Cooperation in the Field of ICT | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Impact of ICT on the Economy | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | + |

| Impact of ICT on Society | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| Institutional Environment Assessment | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + |

| QN | Question Topic | xi | pi | ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | In your opinion, are the five sub-indices mentioned above sufficient to accurately calculate DESI? | 1 | 0.066667 | 20 |

| 2 | 0.17 | 51 | ||

| 3 | 0.186667 | 56 | ||

| 4 | 0.243333 | 73 | ||

| 5 | 0.333333 | 100 | ||

| 2 | In your opinion, are the Communication and Internet Use sub-indexes correlated? | 1 | 0.136667 | 41 |

| 2 | 0.123333 | 37 | ||

| 3 | 0.2 | 60 | ||

| 4 | 0.34 | 102 | ||

| 5 | 0.2 | 60 | ||

| 3 | Do you think it is worth revising the sub-indices? | 1 | 0.056667 | 17 |

| 2 | 0.12 | 36 | ||

| 3 | 0.29 | 87 | ||

| 4 | 0.366667 | 110 | ||

| 5 | 0.166667 | 50 | ||

| 4 | Should the following indicator be included in the DESI calculation? Broadband Internet Access: Percentage of the population with access to high-speed Internet | 1 | 0.086667 | 26 |

| 2 | 0.216667 | 65 | ||

| 3 | 0.293333 | 88 | ||

| 4 | 0.233333 | 70 | ||

| 5 | 0.17 | 51 | ||

| 5 | Should the following indicator be included in the DESI calculation? Citizen Internet Use: Percentage of Citizens Who Regularly Use the Internet | 1 | 0.086667 | 26 |

| 2 | 0.216667 | 65 | ||

| 3 | 0.17 | 51 | ||

| 4 | 0.233333 | 70 | ||

| 5 | 0.293333 | 88 | ||

| 6 | Should the following indicator be included in the DESI calculation? Digital Infrastructure: Assessing the quality and availability of digital infrastructure, including communications networks, hardware, and software | 1 | 0.106667 | 32 |

| 2 | 0.143333 | 43 | ||

| 3 | 0.166667 | 50 | ||

| 4 | 0.236667 | 71 | ||

| 5 | 0.346667 | 104 | ||

| 7 | Should the following indicator be included in the DESI calculation? Digital skills and education: the level of digital literacy of the population, and the availability of educational programs on digital technologies | 1 | 0.143333 | 43 |

| 2 | 0.24 | 72 | ||

| 3 | 0.326667 | 98 | ||

| 4 | 0.2 | 60 | ||

| 5 | 0.09 | 27 | ||

| 8 | Should the following indicator be included in the DESI calculation? Integration of digital technologies in business: The share of enterprises using digital technologies in their operations | 1 | 0.326667 | 98 |

| 2 | 0.24 | 72 | ||

| 3 | 0.2 | 60 | ||

| 4 | 0.143333 | 43 | ||

| 5 | 0.09 | 27 | ||

| 9 | Should the following indicator be included in the DESI calculation? Digital Public Services: Availability and quality of digital government and public services | 1 | 0.143333 | 43 |

| 2 | 0.17 | 51 | ||

| 3 | 0.176667 | 53 | ||

| 4 | 0.213333 | 64 | ||

| 5 | 0.296667 | 89 | ||

| 10 | Should the following indicator be included in the DESI calculation? Innovation and research in digital technologies: The volume of investment in research and development in digital technologies, and the number of patents in this area | 1 | 0.126667 | 38 |

| 2 | 0.163333 | 49 | ||

| 3 | 0.286667 | 86 | ||

| 4 | 0.243333 | 73 | ||

| 5 | 0.18 | 54 | ||

| 11 | Should the following indicator be included in the DESI calculation? Cybersecurity: the level of protection of information systems from cyber threats | 1 | 0.093333 | 28 |

| 2 | 0.08 | 24 | ||

| 3 | 0.1 | 30 | ||

| 4 | 0.276667 | 83 | ||

| 5 | 0.45 | 135 |

| Year | Data for The Netherlands | Data for Sweden | Data for Denmark | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESI Index | Cybersecurity Level | DESI Index | Cybersecurity Level | DESI Index | Cybersecurity Level | |

| 2021 | 45.59 | 0.76 | 45.71 | 0.733 | 46,48 | 0.617 |

| 2022 | 48.06 | 0.885 | 48.74 | 0.81 | 48.69 | 0.852 |

| 2023 | 54.68 | 0.9705 | 55.75 | 0.9455 | 55.97 | 0.926 |

| 2024 | 62.36 | 0.971 | 60.49 | 0.946 | 65.25 | 0.926 |

| No. pp | The Country’s Place in the Ranking by Digital Economy | Target | Necessary Measures (Actions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Lagging” countries are countries that occupy the bottom places in the ranking of countries in the digital economy | Become a leader |

|

| 2 | “Developing” countries | Increase the level of development of the digital economy |

|

| 3 | Countries “leaders” | Maintaining a leadership position |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Denissova, O.; Konurbayeva, Z.; Kulisz, M.; Yussubaliyeva, M.; Suieubayeva, S. Measuring the Digital Economy in Kazakhstan: From Global Indices to a Contextual Composite Index (IDED). Economies 2025, 13, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080225

Denissova O, Konurbayeva Z, Kulisz M, Yussubaliyeva M, Suieubayeva S. Measuring the Digital Economy in Kazakhstan: From Global Indices to a Contextual Composite Index (IDED). Economies. 2025; 13(8):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080225

Chicago/Turabian StyleDenissova, Oxana, Zhadyra Konurbayeva, Monika Kulisz, Madina Yussubaliyeva, and Saltanat Suieubayeva. 2025. "Measuring the Digital Economy in Kazakhstan: From Global Indices to a Contextual Composite Index (IDED)" Economies 13, no. 8: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080225

APA StyleDenissova, O., Konurbayeva, Z., Kulisz, M., Yussubaliyeva, M., & Suieubayeva, S. (2025). Measuring the Digital Economy in Kazakhstan: From Global Indices to a Contextual Composite Index (IDED). Economies, 13(8), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080225