Effect of Human Capital Development on Household Income Growth in Burkina Faso: An Analysis Through a Decomposition Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

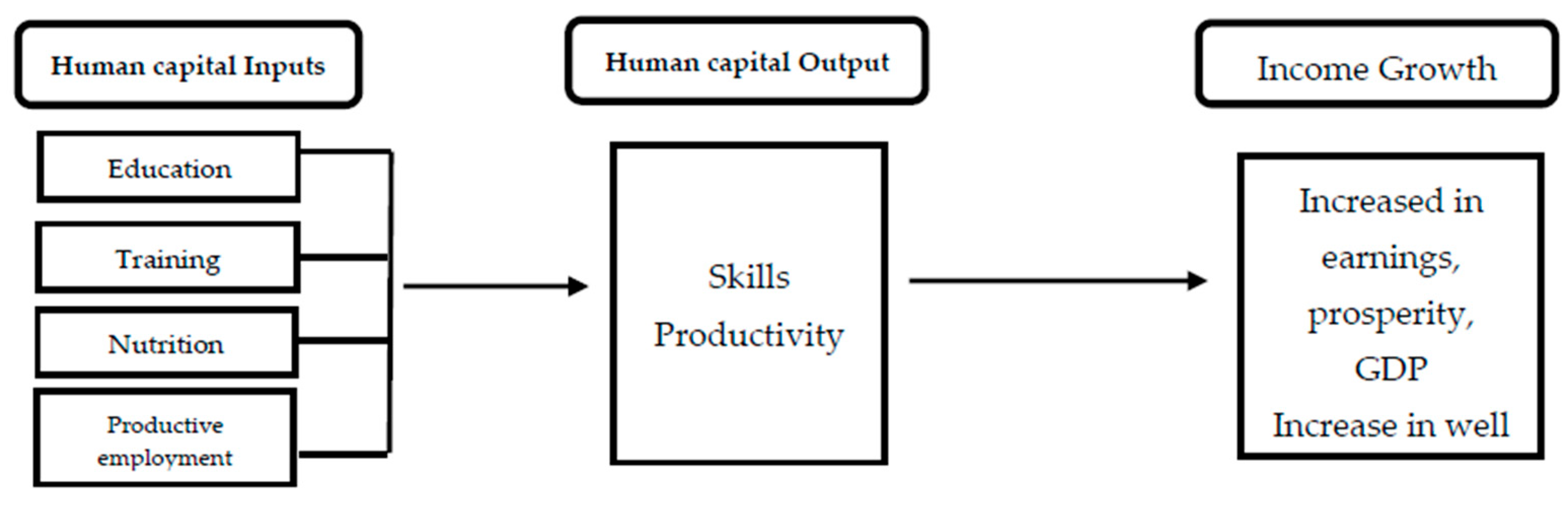

2. Theoretical Framework and Review of the Empirical Literature

2.1. Review of the Theoretical Literature

2.2. Review of the Empirical Literature

2.2.1. Human Capital and Individual Productivity

2.2.2. Human Capital, Poverty, and Income Inequality

3. Methodology and Research Data

3.1. The Methodology

3.2. The Data

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Estimations of the Determinants of the Employed Population’s Prosperity

4.2. Results of the Estimation of the Sources of the Employed Population’s Income Growth Using the Blinder–Oaxaca Decomposition Method

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, A., Hossain, M., & Bose, M. L. (2005). Inequality in the access to secondary education and rural poverty in Bangladesh: An analysis of household and school level data (Vol. 2005). Workshop on Equity and Development in South Asia, India. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H. (2022). Human capital development, poverty and income inequality in Nigeria (1985–2020). Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 4, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (1991). Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 979–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (1995). Split sample instrumental variables estimates of the return to schooling. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 9(3), 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, S. (2001). Education, incomes and poverty in Uganda in the 1990s (Technical Report, CREDIT Research Paper). University of Nottingham. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, S., & Balihuta, A. (1996). Education and agricultural productivity: Evidence from Uganda. Journal of International Development, 8, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref, A. (2011). Perceived impact of education on poverty reduction in rural areas of Iran. Life Science Journal, 8(2), 498–501. [Google Scholar]

- Arestoff, F. (2001). Taux de rendement de l’éducation sur le marché du travail d’un pays en développement: Une analyse micro-économétrique. Revue économique, 52(3), 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadullah, M. N., & Rahman, S. (2009). Farm productivity and efficiency in rural bangladesh: The role of education revisited. Applied Economics, 41(1), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, A., & Admassie, A. (2004). The role of education on the adoption of chemical fertilizer under different socioeconomic environments in Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics, 30(3), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A. (1999). Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development, 27, 2021–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. (1995). Human capital and poverty reduction (Human Resource Development and Operations Working Paper No. HRO 52). World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital (2nd ed.). Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G. S. (1975). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (pp. 13–44). NBER. Available online: http://www.nber.org/books/beck75-1 (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Behrman, J. R. (1993). The economic rationale for investing in nutrition in developing countries. World Development, 21(11), 1749–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennell, P. (1996). Rates of return to education: Does the conventional patten prevail in sub-saharan Africa? World Development, 24, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigsten, A., Isaksson, A., Söderbom, M., Collier, P., Zeufack, A., Dercon, S., Fafchamps, M., Gunning, J. W., Teal, F., Appleton, S., & Gauthier, B. (2000). Rates of return on physical and human capital in Africa’s manufacturing sector. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 48(4), 801–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, I. S., & Rahman, S. (2009). The impact of gender inequality in education on rural poverty in Pakistan: An empirical analysis. European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences, 15, 174–188. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Growth and Development. (2010). Equity and growth in a globalizing world, world bank, 2010 (R. Kanbur, & M. Spence, Eds.). World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-8180-9. eISBN 978-0-8213-8181-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D. J., Johan, S., & Uzuegbunam, I. S. (2019). An anatomy of entrepreneurial pursuits in relation to poverty. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, F., & Heckman, J. (2008). Formulating, identifying and estimating the technology of cognitive and noncognitive skill formation. Journal of Human Resources, 43, 738–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, F., Heckman, J., Lochner, L., & Masterov, D. (2006). Interpreting the evidence on life cycle skill formation. In E. A. Hanushek, & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 1). Elsevier B.V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A., & Zaidi, S. (2002). Guidelines for constructing consumption aggregates for welfare analysis (English) (Living standards measurement study (LSMS) working paper no. LSM 135). The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Epo, B. N., & Baye, F. M. (2013). Determinants of inequality in Cameroon: A regression-based decomposition analysis. Botswana Journal of Economics, 11(15), 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Epo, B. N., & Baye, F. M. (2016). Effects of reducing inequality in household education, health and access to credit on pro-poor growth: Evidence from Cameroon. In Inequality after the 20th century: Papers from the sixth ECINEQ meeting (pp. 59–82). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Epo, B. N., Baye, F. M., Mwabub, G., Mandab, D. K., Ajakaiyec, O., Kiprutod, S., Muriithib, M. K., Samoeid, P. K., Mutegi, R. G., Olecheb, M., Mwangid, T. W., & Wambugub, A. (2021). Human capital, household prosperity and social inequalities in sub saharan Africa (Framework paper of African economic research consortium’s project on human capital development in Africa). African Economic Research Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, R. W. (2004). Health, nutrition, and economic growth. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 52(3), 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A., & Rosenzweig, M. (1995). Learning by doing and learning from others: Human capital and technical change in agriculture. Journal of Political Economy, 103(6), 1176–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, M. (1972). On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. Journal of Political Economy, 80, 223–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, L. J., & Bouis, H. E. (1991). The impact of nutritional status on agricultural productivity: Wage evidence from the Philippines. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 53(1), 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E. (2013). Economic growth in developing countries: The role of human capital. Journal of Economic Growth, 17(4), 204–212. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J. J. (2007). The economics, technology, and neuroscience of human capability formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 13250–13255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israeli, O. A. (2007). Shapley-based decomposition of the R-square of a linear regression. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 5, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafando, B., Thiombiano, N., Pelenguei, E., & Bazié, P. (2022). Analysis of human capital effects: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 12(4), 1738. [Google Scholar]

- Larionova, N. I., & Varlamova, J. A. (2015). Analysis of human capital level and inequality interaction. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1), S3. [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc, A., Pistolesi, N., & Trannoy, A. (2008). Inequality of opportunities vs inequality of outcomes: Are western societies all alike? Review of Income and Wealth, 54, 513–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Y. (1991). Education and innovation adoption in agriculture: Evidence from hybrid rice in China. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, 73(3), 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockheed, M. E., Jamison, D. T., & Lau, L. J. (1979). Farmer education and farm efficiency: A survey. ETS Research Report Series, 2, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, J. (1991). Education and unemployment (NBER Working Paper No. 3838). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de l’économie et des finances [Ministry of the Economy and Finance]. (2001). Etude nationale prospective «Burkina 2025». Etude rétrospective macro-économique. Ministère de l’économie et des finances (MEF).

- Ministère de l’économie et des finances [Ministry of the Economy and Finance. (2004). Cadre Stratégique de lutte contre la pauvreté. Ministère de l’économie et des Finances (MEF).

- Ministère de l’économie et des finances [Ministry of the Economy and Finance. (2011). Stratégie de croissance accélérée et de développement durable 2011–2015. Ministère de l’économie et des Finances (MEF).

- Ministère de l’économie et des finances et du développement [Ministry of the Développent, Economy and Finance]. (2016). Plan national de développement économique et social (PNDES) 2016–2020. Ministère de l’économie, des Finances et du Développement (MINEFID).

- Moser, C. O. N. (2006). Asset-based approaches to poverty reduction in a globalized context: An introduction to asset accumulation policy and summary of workshop findings (Working Paper 01). Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, C., Mishi, S., & Ncwadi, R. (2022). Human capital development, poverty and income inequality in the Eastern Cape Province. Development Studies Research, 9(1), 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathans, L., Oswald, F., & Nimon, K. (2012). Interpreting multiple linear regression: A guidebook of variable importance. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 17, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R. R., & Phelps, E. S. (1966). Investment in humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. The American Economic Review, 56(1/2), 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, S., & Oaxaca, R. (2004). Wage decompositions with selectivity-corrected wage equations: A methodological note. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 2(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njong, A. M. (2010). The effects of educational attainment on poverty reduction in Cameroon. Journal of Education Administration and Policy Studies, 2(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Oaxaca, L. R. (1973). Male-female wage differentials in urban labour markets. International Economic Review, 14(3), 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primature. (2021). Deuxième Plan national de développement économique et social (PNDES-II) 2021–2025. Primature. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, M., & Klasen, S. (2013). Revisiting the role of education for agricultural productivity. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 95(1), 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridell, S. (2011). The impact of education on employment incidence and re-employment success: Evidence from the US labour markets. Labour Economics, 18(4), 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, J. E. (1998). Equality of opportunity. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer, J. E. (2002). Equality of opportunity: A progress report. Social Choice and Welfare, 19, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98, S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairmaly, F. A. (2023). Human capital development and economic growth: A literature review on information technology investment, education, skills, and productive labour. Jurnal Minfo Polgan, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, M., Gow, J., & Vink, N. (2020). Effects of environmental quality on agricultural productivity in Sub–Saharan African countries: A second generation panel based empirical assessment. Science of the Total Environment, 741, 140520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M. E. (2009). Human capital and the quality of education in a poverty trap model. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI), Oxford Department of International Development. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T. P. (Ed.). (1993). Investments in women’s human capital. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T., & Tansel, A. (1997). Wage and labor supply effects of illness in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana: Instrumental variable estimates for days disabled. Journal of Development Economics, 53, 251–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. American Economic Review, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T. W. (1962). Investment in human beings. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T. W. (1975). The value of the ability to deal with disequilibria. Journal of Economic Literature, 13(35), 827–846. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T. W. (1982). Investing in people: The economics of population quality. University of California Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (1997). On economic inequality. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharada, W., & Knight, J. (2004). Externality effects of education: Dynamics of the adoption and diffusion of an innovation in rural ethiopia. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53(1), 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A., & Mohanty, S. K. (2010). Economic proxies, household consumption and health estimates. Economic and Political Weekly, 45, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, J., & Thomas, D. (1998). Health, nutrition, and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(2), 766–817. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, P. N. (2014). Gary becker’s early work on human capital: Collaborations and distinctiveness (pp. 1–20). Springer. ISSN 2193-8997. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstein, R. L., & Lazar, N. A. (2016). The ASA statement on p-Values: Context, process, and purpose. American Statistical Association, 70, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, F. (1970). Education in production. Journal of Political Economy, 78(1), 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widarni, E. L., & Bawono, S. (2020). Human capital investment for better business performance. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355116256_Human_Capital_Investment_For_Better_Business_Performance (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- World Bank. (2005). Introduction to poverty analysis. World Bank Institute. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/775871468331250546/pdf/902880WP0Box380okPovertyAnalysisEng.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Yang, Y., Zhou, L., Zhang, C., Luo, X., Luo, Y., & Wang, W. (2022). Public health services, health human capital, and relative poverty of rural families. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 11089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuko, A., Kim, J. M., & Kimhi, A. (2006). Determinants of income inequality among Korean farm households (Economic Research Centre, Discussion paper, No. 161). School of Economics, Nagoya University. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Variables’ Definition | 2009 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCEX | Per capita expenditure | 155,585.9 | 282,418.2 |

| PCEXD | Expenditure per capita adjusted for fluctuations in the price of the basket of goods | 155,585.9 | 223,786.2 |

| YEDUC | Number of years of education | 1.45 | 2.46 |

| Age | Age | 34.87 | 34.39 |

| HFDS | Food Diversity Score | 7.68 | 9.60 |

| Female (%) | (=1 if female) | 54.39 | 52.70 |

| Urban (%) | (=1 if urban area) | 27.79 | 39.19 |

| Married (%) | (=1 if married) | 92.18 | 76.57 |

| Under-employment (%) | Average household underemployment rate | 69.40 | 78.22 |

| Health_Centre (%) | (=1 if a person frequents a modern health centre) | 8.54 | 13.76 |

| alpha_pere (%) | (=1 if father is literate) | 10.96 | 12.95 |

| alpha_mere (%) | (=1 if mother is literate) | 5.30 | 6.02 |

| access_health (%) | (=1 if a person has access to a health centre) | 71.33 | 92.23 |

| access_education (%) | (=1 if a person has access to a formal education centre) | 45.37 | 62.81 |

| Sector (%) | (=1 if in formal employment) | 2.56 | 4.34 |

| N | Number of observations | 19,894 | 4055 |

| Statistics | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Hansen J statistic (overidentification test) | 1.284 | 0.2571 |

| Under-identification test | 36.793 | 0.000 |

| Endogeneity test of endogenous regressors | 355.747 | 0.000 |

| OLS | IV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | Z | p > z | Coef. | z | p > z | |

| YEDUC | 0.047 | 35.97 | 0.000 | 0.059 | 5.79 | 0.000 |

| Health_Centre | 0.154 | 11.61 | 0.000 | 3.425 | 5.4 | 0.000 |

| HFDS | 0.075 | 33.78 | 0.000 | 0.304 | 3.22 | 0.001 |

| Years2018 | 0.443 | 39.13 | 0.000 | −0.159 | −0.88 | 0.381 |

| Female | −0.039 | −4.91 | 0.000 | −0.124 | −4 | 0.000 |

| Urban | 0.255 | 24.64 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.16 | 0.874 |

| Married | −0.023 | −1.76 | 0.079 | −0.067 | −1.81 | 0.070 |

| Age | 0.003 | 1.54 | 0.124 | |||

| age2 | 0.000 | −1.24 | 0.215 | |||

| Underemployment | −0.232 | −24.1 | 0.000 | −0.068 | −1.44 | 0.151 |

| Grand_est | 0.072 | 6.86 | 0.000 | 0.058 | 1.82 | 0.069 |

| Grand_centre | 0.103 | 8.67 | 0.000 | 0.094 | 1.89 | 0.059 |

| Grand_sahel | 0.108 | 9.76 | 0.000 | 0.292 | 4.07 | 0.000 |

| Ouaga | 0.360 | 19.93 | 0.000 | 0.290 | 5.74 | 0.000 |

| _cons | 10.950 | 245.83 | 0.000 | 8.984 | 12.16 | 0.000 |

| Coef. | z | p > z | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential | |||

| Prediction_1 | 12.301 | 1215.42 | 0.000 |

| Prediction_2 | 11.637 | 2263.66 | 0.000 |

| Difference | 0.664 | 58.48 | 0.000 |

| Endowments | |||

| YEDUC | 0.033 | 10.86 | 0.000 |

| Health_Centre | 0.010 | 6.59 | 0.000 |

| HFDS | 0.227 | 21.56 | 0.000 |

| Years2009 | 0.000 | ||

| Female | 0.001 | 1.46 | 0.144 |

| Urban | 0.023 | 8.51 | 0.000 |

| Married | 0.002 | 0.78 | 0.433 |

| Age | −0.006 | −1.88 | 0.060 |

| age2 | 0.006 | 1.82 | 0.069 |

| Underemployment | −0.009 | −3.82 | 0.000 |

| Grand_est | 0.001 | 1.09 | 0.276 |

| Grand_centre | −0.001 | −0.71 | 0.479 |

| Grand_sahel | 0.001 | 0.88 | 0.377 |

| Ouaga | −0.002 | −1.19 | 0.235 |

| Total | 0.285 | 21.47 | 0.000 |

| Coefficients | |||

| YEDUC | −0.047 | −7.49 | 0.000 |

| Health_Centre | 0.009 | 2.46 | 0.014 |

| HFDS | 0.482 | 8.72 | 0.000 |

| Years2009 | 0.000 | ||

| Female | 0.005 | 0.6 | 0.546 |

| Urban | −0.025 | −2.89 | 0.004 |

| Married | 0.035 | 1.74 | 0.081 |

| Age | 0.441 | 2.55 | 0.011 |

| age2 | −0.204 | −2.35 | 0.019 |

| Underemployment | −0.059 | −3.7 | 0.000 |

| Grand_est | 0.026 | 4.48 | 0.000 |

| Grand_centre | 0.017 | 4.14 | 0.000 |

| Grand_sahel | −0.028 | −5.95 | 0.000 |

| Ouaga | 0.009 | 3.87 | 0.000 |

| _cons | −0.215 | −2.04 | 0.041 |

| Total | 0.446 | 43.3 | 0.000 |

| Interaction | |||

| YEDUC | 0.019 | 6.75 | 0.000 |

| Health_Centre | −0.003 | −2.39 | 0.017 |

| HFDS | −0.097 | −8.65 | 0.000 |

| Years2009 | 0.000 | ||

| Female | 0.000 | 0.58 | 0.564 |

| Urban | 0.007 | 2.83 | 0.005 |

| Married | 0.007 | 1.74 | 0.082 |

| Age | 0.006 | 1.74 | 0.083 |

| age2 | −0.006 | −1.67 | 0.094 |

| Underemployment | 0.003 | 2.7 | 0.007 |

| Grand_est | −0.001 | −1.07 | 0.285 |

| Grand_centre | 0.000 | 0.7 | 0.484 |

| Grand_sahel | −0.005 | −3.73 | 0.000 |

| Ouaga | 0.001 | 1.14 | 0.253 |

| Total | −0.067 | −5.45 | 0.000 |

| Number of observations | 23,949 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siri, A.; Combary, O. Effect of Human Capital Development on Household Income Growth in Burkina Faso: An Analysis Through a Decomposition Method. Economies 2025, 13, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070202

Siri A, Combary O. Effect of Human Capital Development on Household Income Growth in Burkina Faso: An Analysis Through a Decomposition Method. Economies. 2025; 13(7):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070202

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiri, Alain, and Omer Combary. 2025. "Effect of Human Capital Development on Household Income Growth in Burkina Faso: An Analysis Through a Decomposition Method" Economies 13, no. 7: 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070202

APA StyleSiri, A., & Combary, O. (2025). Effect of Human Capital Development on Household Income Growth in Burkina Faso: An Analysis Through a Decomposition Method. Economies, 13(7), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070202