Modelling South Africa’s Economic Transformation and Growth: A Prospective and Retrospective Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Patterns of Growth and Structural Change in South Africa Since 1994

3.1. Overview of South Africa’s Economic Transformation Policies and Initiatives Since 1994

3.1.1. Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) 1994

3.1.2. Growth, Employment, and Redistribution (GEAR) Strategy 1996

3.1.3. Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative (ASGISA) 2005

3.1.4. National Development Plan (NDP) 2011

3.1.5. South Africa and Global Development Strategies: SDG Agenda 2030 and Africa 2063

3.1.6. Economic Reform and Reconstruction Programme

3.1.7. Operation Vulindlela 2023

3.1.8. Industrial Policy Action Plans (IPAPs)

3.1.9. Integrated Development Plans (IDPs)

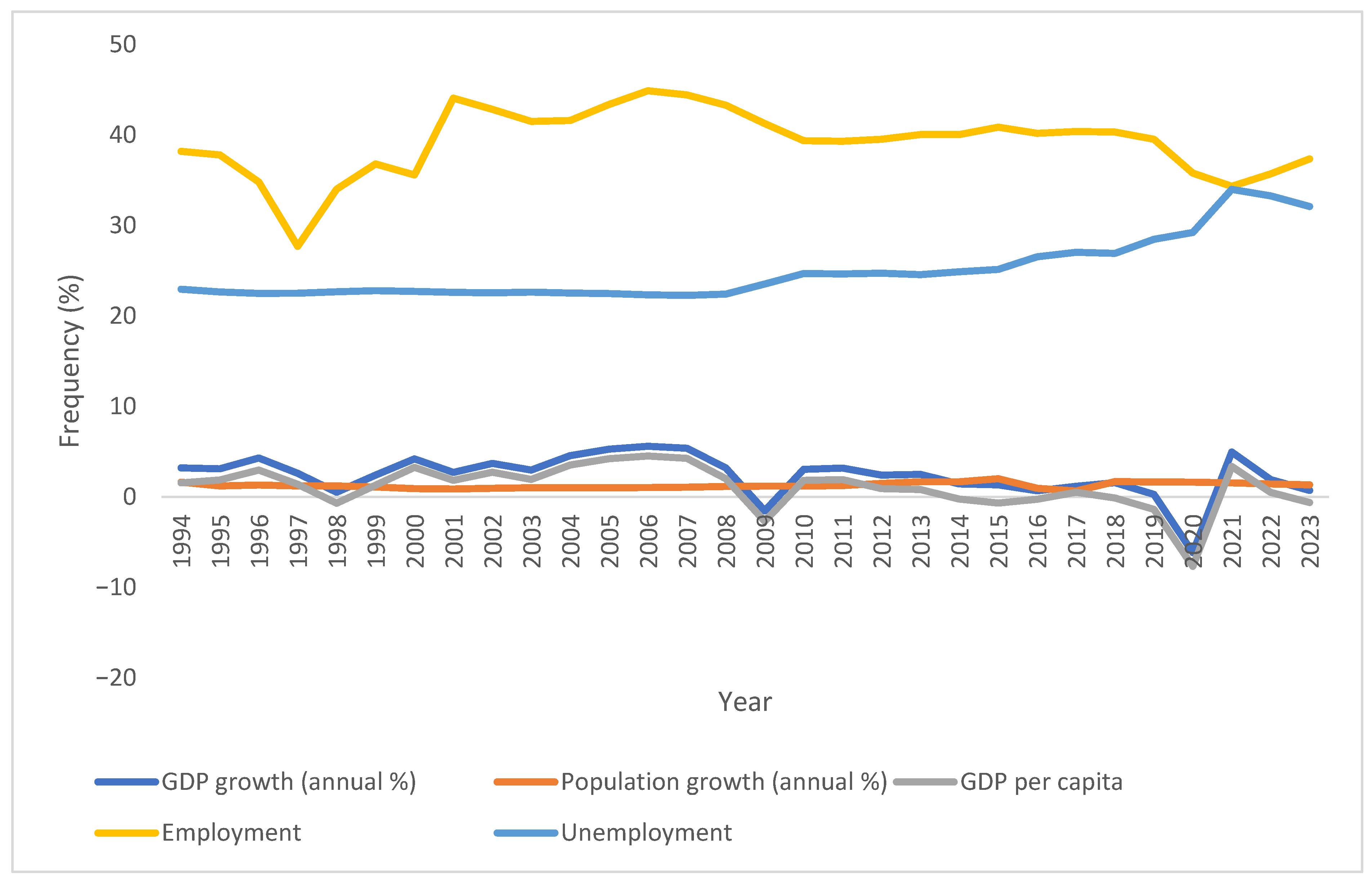

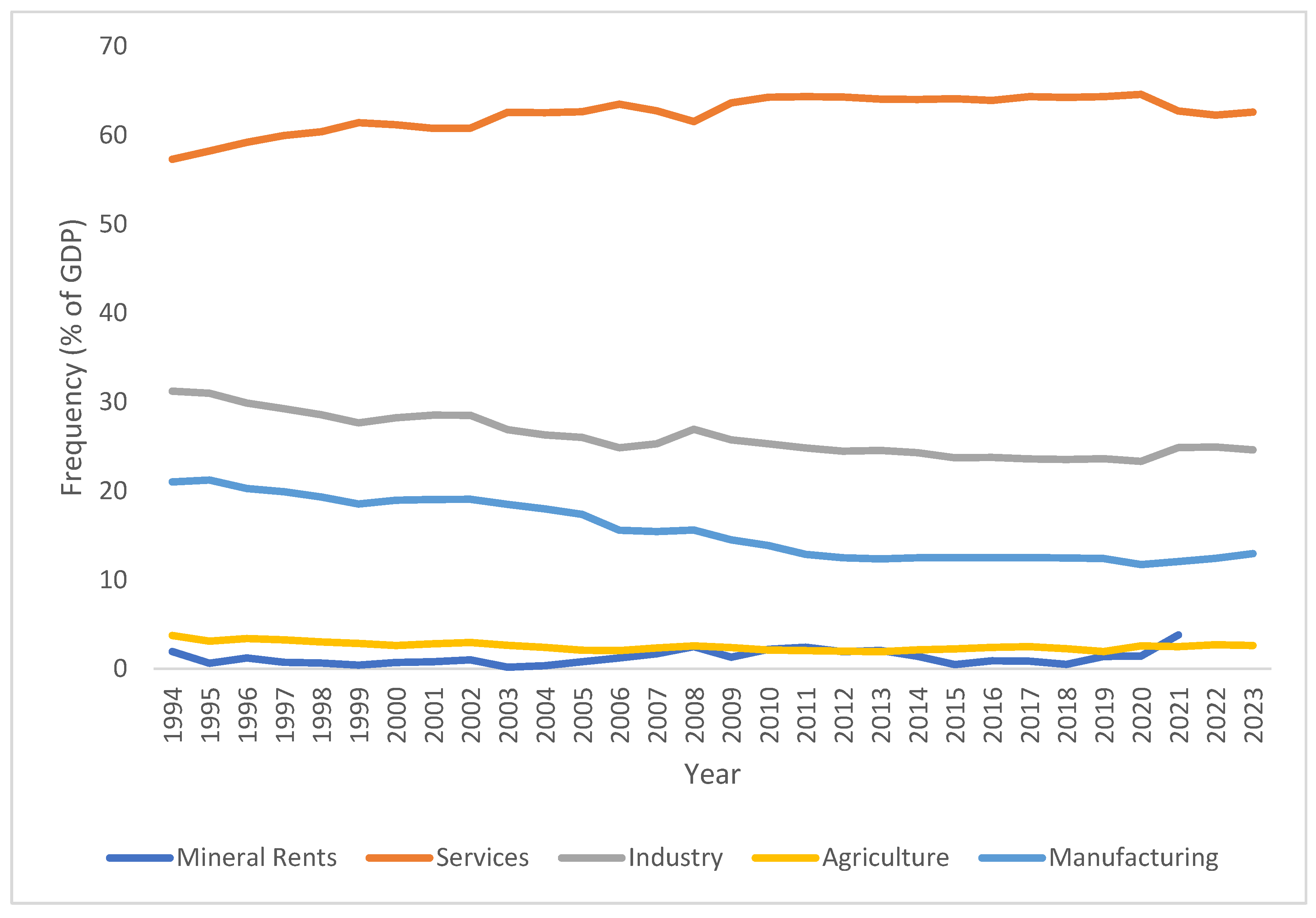

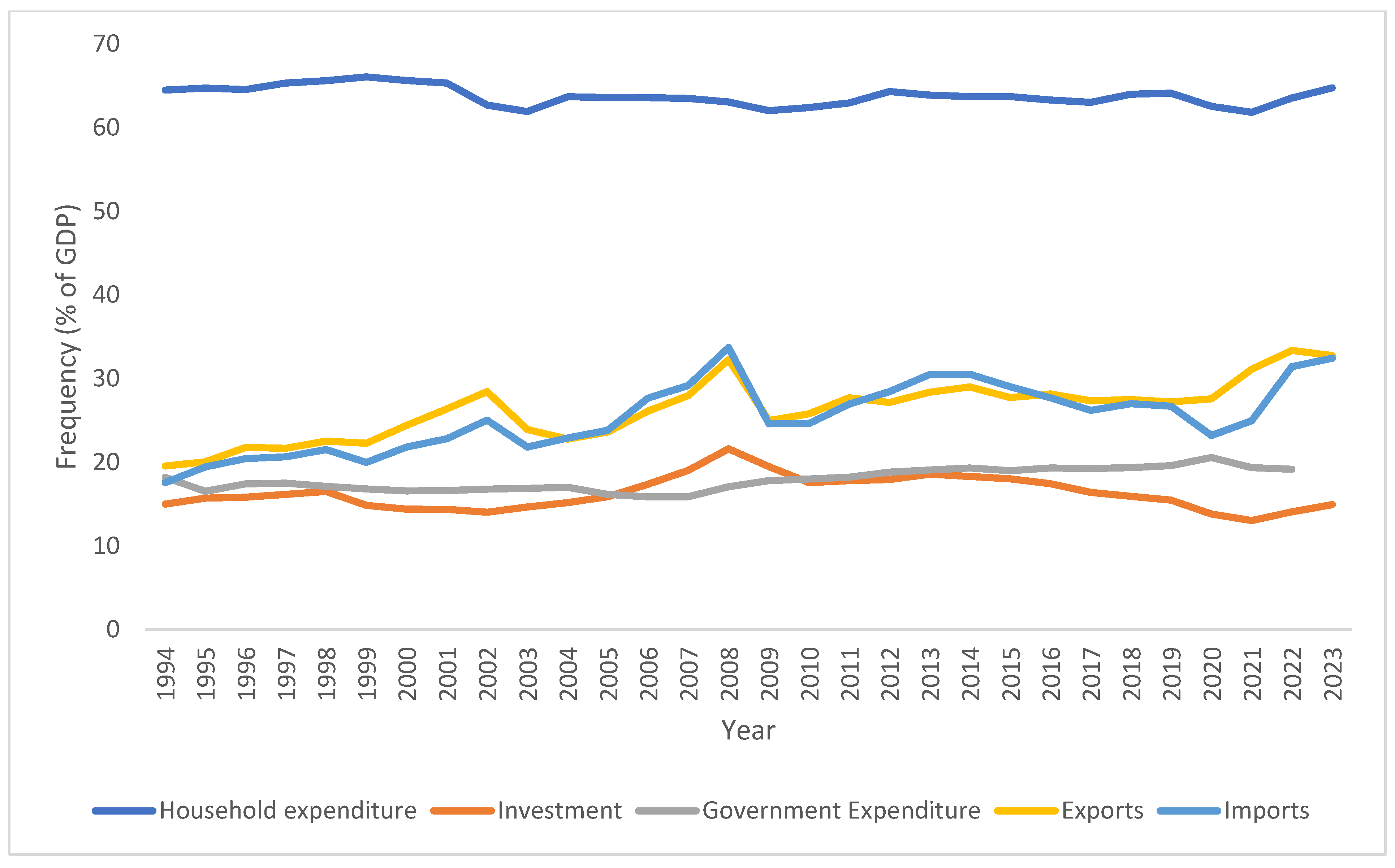

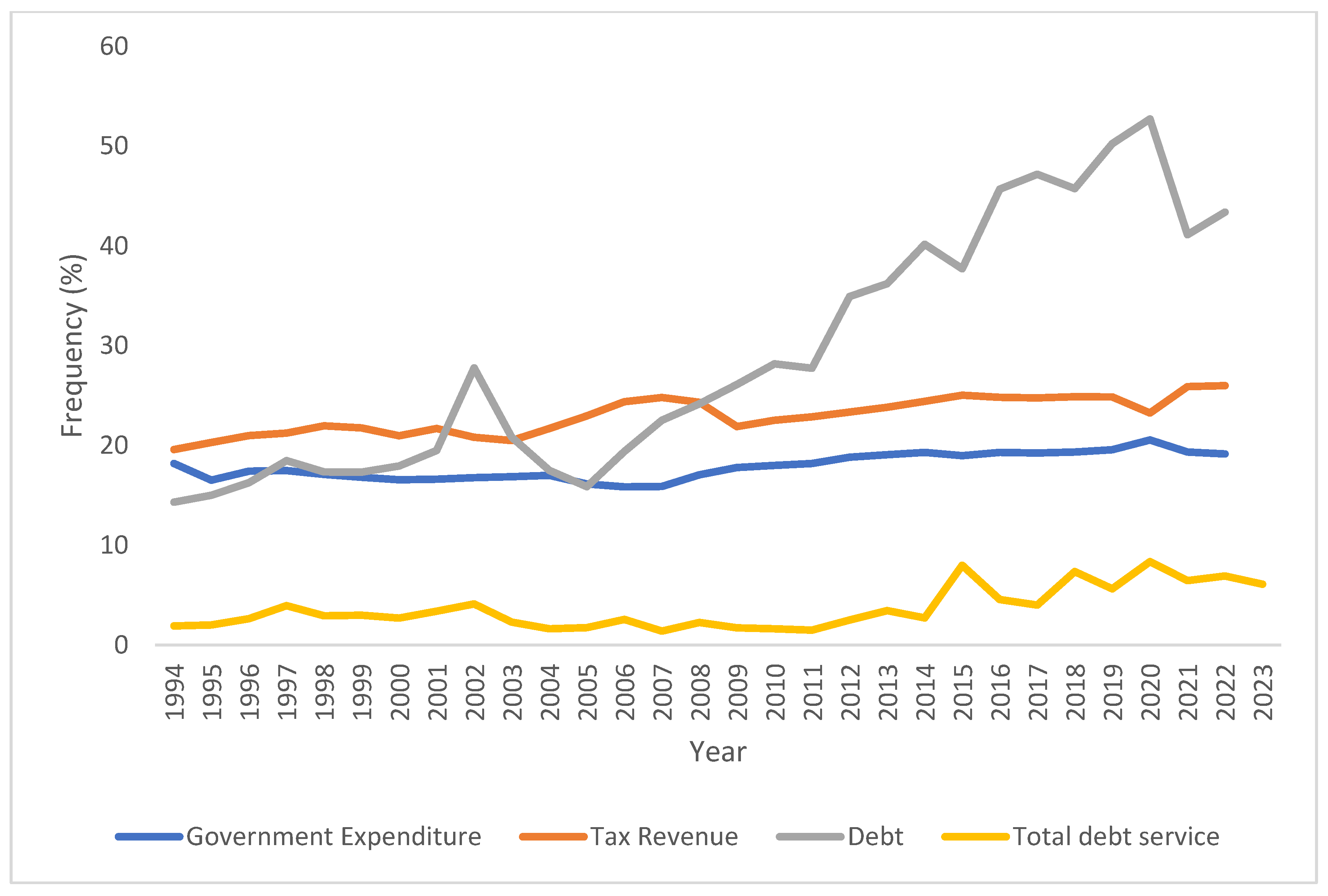

3.2. Growth Patterns and Structural Change Since 1994

4. Modelling Framework and Scenarios

4.1. The Model

- Unemployment

- Productivity

4.2. Simulation Scenarios

- Business-as-Usual Scenario (BAU)

- Stimulating Inclusive Economic Growth

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, P. D., & Parmenter, B. R. (2013). Computable general equilibrium modelling of environmental issues in Australia. In Handbook of computable general equilibrium modelling (Vol. 1, pp. 553–657). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjasi, C. K., & Yu, D. (2021). Investigating South Africa’s economic growth: The role of financial sector development. Journal of Business and Economic Options, 4(3), 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Adjei, P. O. W., Kyei, P. O., & Afriyie, K. (2014). Global economic crisis and socio-economic vulnerability historical experience and lessons from the “Lost Decade” for Africa in the 1980s. Ghana Studies, 17(1), 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allie-Edries, N., & Mupela, E. (2019). Business incubation as a job creation model: A comparative study of business incubators supported by the South African Jobs Fund. Africa Journal of Public Sector Development and Governance, 2(2), 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, F. J., Cardenete, M. A., & Romero, C. (2010). Designing public policies: An approach based on multi-criteria analysis and computable general equilibrium modelling. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetta, M., Beverelli, C., Cadot, O., Fugazza, M., Grether, J.-M., Helble, M., Nicita, A., & Piermartini, R. (2012). A practical guide to trade policy analysis (236p). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. World Trade Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Baldacci, E., Clements, B., Gupta, S., & Cui, Q. (2008). Social spending, human capital, and growth in developing countries. World Development, 36(8), 1317–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R., & Forslid, R. (2023). Globotics and development: When manufacturing is jobless and services are tradeable. World Trade Review, 22(3–4), 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, L. (2005). CGE modelling of environmental policy and resource management. Handbook of Environmental Economics, 3, 1273–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Bhorat, H., Hill, R., Khan, S., Lilenstein, K., & Stanwix, B. (2020). The employment tax incentive scheme in South Africa: An impact assessment. Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (1995). An introduction to the wage curve. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, E., & Makina, D. (2011). Financial regulation and supervision: Theory and practice in South Africa. The International Business & Economics Research Journal (Online), 10(11), 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, M., Behrens, R., & McLachlan, N. (2024). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on public transport in South Africa: A Cape Town study. In International perspectives on public transport responses to COVID-19 (pp. 235–249). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Budlender, J., & Ebrahim, A. (2021). Estimation of employment responses to South Africa’s employment tax incentive. No. 2021/118. WIDER. [Google Scholar]

- Carri, B. (2008). CGE approaches to policy analysis in developing countries: Issues and perspectives. SPERA Working Paper 2/2008. Centre for Economic Development, Health, and the Environment. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, M., & Kobus, S. (2025). Is South Africa back on track? MoneyMarketing, 2025(1), 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chitiga-Mabugu, M., Henseler, M., Maisonnave, H., & Mabugu, R. (2025). Financing basic income support in South Africa under fiscal constraints. World Development Perspectives, 37, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, G. C. (2015). China’s economic transformation. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ciaffi, G., Deleidi, M., & Mazzucato, M. (2024). Measuring the macroeconomic responses to public investment in innovation: Evidence from OECD countries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 33(2), 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corder, C. K. (1997). The reconstruction and development programme: Success or failure? Social Indicators Research, 41, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dappe, M. H., & Lebrand, M. (2024). Infrastructure and structural change in Africa. The World Bank Economic Review, 38(3), 483–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dare, C., Du Plessis, S., & Jansen, A. (2019). Tax revenue mobilisation: Estimates of South Africa’s personal income tax gap. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 22(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- das Nair, R. (2021). Regional value chains and integration of South Africa. In The Oxford handbook of the South African economy (p. 396). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R., & Thurlow, J. (2010). Formal-informal economy linkages and unemployment in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 78(4), 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaluwé, R., Maes, D., Declerck, I., Cools, A., Wuyts, B., De Smet, S., & Janssens, G. P. J. (2013). Changes in back fat thickness during late gestation predict colostrum yield in sows. Animal, 7(12), 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jongh, J., & Mncayi, P. (2018). An econometric analysis on the impact of business confidence and investment on economic growth in post-apartheid South Africa. International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies, 10(1), 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Deleidi, M., & Mazzucato, M. (2019). Putting austerity to bed: Technical progress, aggregate demand, and the supermultiplier. Review of Political Economy, 31(3), 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervis, K., de Melo, J., & Robinson, S. (1982). General equilibrium models for development policy (pp. xv–547). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, M. M. (2023). Structural transformation of the indian economy: Past performance and way forward to 2047. In India 2047: High income with equity (pp. 21–28). Oakbridge Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Devarajan, S., & Robinson, S. (2013). Contribution of computable general equilibrium modelling to policy formulation in developing countries. In Handbook of computable general equilibrium modelling (Vol. 1, pp. 277–301). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C., Cerbone, D., & Van Zijl, W. (2020). The South African government’s response to COVID-19. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 32(5), 797–811. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, X., Ellis, M., McMillan, M., & Rodrik, D. (2024). Africa’s manufacturing puzzle: Evidence from Tanzanian and Ethiopian companies. The World Bank Economic Review, 39(2), 308–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X., Kweka, J., McMillan, M., & Qureshi, Z. (2020). Economic transformation in Africa from the bottom up: New evidence from Tanzania. The World Bank Economic Review, 34(Suppl. S1), S58–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P. (2006). Evidence-based trade policy decision making in Australia and the development of computable general equilibrium modelling (pp. 1–27). CPS General Working Paper G-163. Centre of Policy Studies (CoPS). [Google Scholar]

- Dlamini, B. I., & Zogli, L. K. J. (2021). Assessing the integrated development plan as a performance management system in a municipality. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, L. (2024). Trade and industrial policy for South Africa’s future: Policy paper 31. ERSA Working Paper Series. ERSA. [Google Scholar]

- Erumban, A. A., & de Vries, G. J. (2024). Structural change and reduction in poverty in developing economies. World Development, 181, 106674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedderke, J. W. (2014). Exploring unbalanced growth in South Africa: Understanding the sectoral structure of the South African economy. South African Reserve Bank Working Paper Series. South African Reserve Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, S., & Gelb, A. (1991). The process of socialist economic transformation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(4), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofana, I., Chitiga-Mabugu, M. R., & Mabugu, R. (2023). Is africa on track to ending poverty by 2030? Journal of African Economies, 32, ii87–ii98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofana, I., Mabugu, R., Camara, A., & Abidoye, B. (2024). Ending poverty and accelerating growth in South Africa, through the expansion of its social grant system. Journal of Policy Modelling, 46(6), 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, D. J., & Blom, P. P. (2022). Challenges, strategies, and solutions to manage public debt in South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 13(1), 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, P. K., & Reed, T. (2020). Demand-side constraints in development. Development Research. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, P. K., & Reed, T. (2023). Presidential address: Demand side constraints in development. The role of market size, trade and (in) equality. Econometrica, 91(6), 1915–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollin, D., & Kaboski, J. P. (2023). New views of structural transformation: Insights from recent literature. Oxford Development Studies, 51(4), 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, P., Opoku, M. O., & Kwakwa, P. A. (2022). Relationship among corporate reporting, corporate governance, going concern, and investor confidence: Evidence from listed banks in sub-Saharan Africa. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2152157. [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi, N., Cheng, C. F. C., & Smeets, E. (2017). The importance of manufacturing in economic development: Has this changed? World Development, 93, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, F., Merven, B., Hughes, A., Marquard, A., & Ranchhod, V. (2025). Estimating the economic and redistributive impacts of mitigation in South Africa. Climate and Development, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, R., O’Brien, T., Fortunato, A., Lochmann, A., Shah, K., Venturi Grosso, L., Enciso Valdivia, S., Vashkinskaya, E., Ahuja, K., Klinger, B., & Sturzenegger, F. (2023). Growth through inclusion in South Africa. Center for International Development at Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Hlatshwayo, M. (2017). The expanded public works programme: Perspectives of direct beneficiaries. TD: The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 13(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C., & Un, K. (2011). Cambodia’s economic transformation. NIAS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jayne, T. S., Chamberlin, J., & Benfica, R. (2018). Africa’s economic transformation that is unfolding. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(5), 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J. (2024). The realisation of the Lewis turning point is seen from the labour production efficiency of urban and rural sectors—A statistical study based on data. Modern Economy, 15(10), 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. S., & Thorbecke, E. (2003). The impact of public education expenditure on human capital, growth, and poverty in Tanzania and Zambia: A general equilibrium approach. Journal of Policy Modeling, 25(8), 701–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khambule, I., & Mdlalose, M. (2022). COVID-19 and state coordinated responses in South Africa’s emerging developmental state. Development Studies Research, 9(1), 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiková, A. (2015). Reconstruction and development programme as a tool of socioeconomic transformation in South Africa. Modern Africa: Politics, History and Society, 3(1), 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon, G. G., & Knight, J. (2006). How flexible are wages in response to local unemployment in South Africa? Industrial and Labour Relations Review, 59, 471–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, M., Somcutean, C., & Wedemeier, J. (2023). Productivity, smart specialisation, and innovation: Empirical findings on EU macroregions. Region: The Journal of ERSA, 10(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefophane, M. H. (2024). Unemployment, policy responses, and challenges in South Africa: A sectoral analysis. Books on Demand. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C. M. (2021). The Latin American economies since c. 1950: Ideas, policies, and structural change. In Setbacks and advances in the modern Latin American economy (pp. 204–239). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, W. A. (1954). A model of dualistic economics. American Economic Review, 36(1), 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lottan, T. P., & Scheepers, C. B. (2024). YES: Leading a youth employment service towards increasing impact. Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies, 14(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, L., & Chartier, F. (2017). Financial inclusion in South Africa: An integrated framework for financial inclusion of vulnerable communities in South Africa’s regulatory system reform. Journal of Comparative Urban Law and Policy, 1(1), 13. [Google Scholar]

- Mabasa, K. (2014). Building a bureaucracy for the South African developmental state an institutional-policy analysis of the post-apartheid political economy. University of Pretoria (South Africa). [Google Scholar]

- Mabugu, R. E., Fofana, I., & Chitiga-Mabugu, M. (2025). Evaluating impacts of agriculture-led investments on Sub-Saharan African countries’ poverty and growth. International Review of Applied Economics, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabugu, R. E., Fofana, I., & Mabugu-Chitiga, M. (2015). Pro-poor tax policy changes in South Africa: Potential and Limitations. Journal of African Economies, 24(2), 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamokhere, J. (2022). Leave no one behind in a participative integrated development planning process in South Africa. International Journal of Research in Business & Social Sciences, 11, 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Mamokhere, J., & Meyer, D. F. (2022). A review of mechanisms used to improve community participation in the integrated development planning process in South Africa: An empirical review. Social Sciences, 11(10), 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manete, T. K. J. (2018). The impact of investment on economic growth and employment in South Africa: A sectoral approach [Doctoral dissertation, North-West University, Vaal Triangle Campus]. [Google Scholar]

- Marumo, M. (2020). The jobs fund. TAXtalk, 2020(85), 88–89. [Google Scholar]

- Masipa, M. H. (2021). An analysis of the integrated development planning (IDP) process in Blouberg Local Municipality [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria]. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaleki, C. (2024). Decomposing South Africa’s fiscal dynamics through successive policy regimes in the post-apartheid dispensation. Journal of Public Administration, 59(2), 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbatha, S., & Mason, A. M. (2023). Examining the effectiveness of the South African Apparel Industry’s systems of innovation. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 12(1), 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbeki, T. (2004). State of the nation address. Available online: https://sahistory.org.za/archive/2004-president-mbeki-state-nation-address-6-february-2004-national-elections (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- McMillan, M. S., & Harttgen, K. (2014). What is driving the “African Growth Miracle”? No. w20077. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, M. S., & Zeufack, A. (2022). Growth and industrialisation of labour productivity in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(1), 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, E. B., Owusu, S., & Foster-McGregor, N. (2023). Productive efficiency, structural change, and catch-up within Africa. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 65, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meth, C. (2011). Employer of last resort? South Africas Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP).

- Mhlaba, N., & Phiri, A. (2019). Is public debt harmful to economic growth? New evidence from South Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1603653. [Google Scholar]

- Montaud, J. M., Dávalos, J., & Pécastaing, N. (2019). Potential effects of infrastructure expansion in Peru: A general equilibrium model-based analysis. Applied Economics, 52(27), 2895–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosala, S. (2022). The South African economic reconstruction and recovery plan as a response to the South African economic crisis. Journal of BRICS Studies, 1(1), 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mseleku, Z. (2023). Neoliberalism and the downfall of the growth, employment, and redistribution (GEAR) strategy in South Africa: Key lessons for future development policies. African Journal of Development Studies, 13(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaudzi, D. J., Francis, J., Zuwarimwe, J., & Chakwizira, J. (2023). Main criteria of credible integrated development planning in local government: Mbombela city, Ehlanzeni district, South Africa. International Journal of Public Leadership, 19(4), 316–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, V., & Maré, A. (2015). Implementing the national development plan? Lessons from co-ordinating grand economic policies in South Africa. Politikon, 42(3), 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncanywa, T., & Masoga, M. M. (2018). Can public debt stimulate public investment and economic growth in South Africa? Cogent Economics & Finance, 6(1), 1516483. [Google Scholar]

- Newfarmer, R. S., Page, J., & Tarp, F. (2019). Industries without smokestacks and structural transformation in Africa. In Industries without smokestacks (Vol. 1). Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/industries-without-smokestacks-2 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Nokulunga, M., Didi, T., & Clinton, A. (2018, March 6–8). Challenges of reconstruction and development programme (RDP) houses in South Africa. International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management (Vol. 2018, No. SEP, pp. 1695–1702), Bandung, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Ntombela, S., Kalaba, M., & Bohlmann, H. (2018). Estimating trade elasticities for South Africa’s agricultural commodities for use in policy modelling. Agrekon, 57(3–4), 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, N. M. (2004). Is financial development still a boost to economic growth? Causal evidence from South Africa. Savings and Development, 28(1), 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Onyango, G., & Ondiek, J. O. (2022). Open innovation during the responses to COVID19 pandemic policies in South Africa and Kenya. Politics & Policy, 50(5), 1008–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Analytica. (2024). South Africa’s water supply crisis may continue to worsen. Emerald Expert Briefings, (oxan-db). [Google Scholar]

- Pamba, D. (2022). The link between tax revenue components and economic growth: Evidence from South Africa. An ARDL approach. International Journal of Management Research and Economics, 2(1), 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A. M., & Shoven, J. B. (1988). Survey of dynamic computational general equilibrium models for tax policy evaluation. Journal of Policy Modelling, 10, 401–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S. (2004, October 28–29). The expanded public works programme (EPWP). Conference on Overcoming Underdevelopment in South Africa’s Second Economy, Pretoria, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Ranchhod, V., & Finn, A. (2015). Estimating the effects of South Africa’s youth employment tax incentive: An update. Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, University of Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Rapanyane, M. B. (2021). SACP and ANC-led alliance government’s inclination to the national democratic revolution: A review of implementation successes and failures. Journal of Nation-Building and Policy Studies, 5(1), 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, G. (2025). A tale of no cities? The neglect of cities in South Africa’s post-apartheid national economic policies. Area Development and Policy, 10(1), 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (2011). The future of economic convergence. No. w17400. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, D. (2013). Structural change, fundamentals, and growth: An overview. Institute for Advanced Study, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, D. (2014). The past, present, and future of economic growth. Challenge, 57(3), 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (2022). Prospects for global economic convergence under new technologies. In Z. Qureshi (Ed.), An inclusive future? Technology, new dynamics, and policy challenges (pp. 65–82). Brookings. [Google Scholar]

- Sethole, F. R., & Sebola, E. M. (2020). Reconstruction and development programme: An Afrocentric analysis of the historical developments, challenges and remedies [online]. Available online: https://scholar.google.co.za/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=Etdzs-cAAAAJ&citation_for_view=Etdzs-cAAAAJ:hqOjcs7Dif8C (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Shipalana, P. (2019). Digitising financial services: A tool for financial inclusion in South Africa. South African Institute of International Affairs, 1–38. Available online: https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Occasional-Paper-301-shipalana.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Solow, R. (1954). VI. The survival of mathematical economics. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 36, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X., Feng, Q., Xia, F., Li, X., & Scheffran, J. (2021). Impacts of the change in urban land use structure on sustainable city growth in China: A population-density dynamics perspective. Habitat International, 107, 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Africa. (1994). White paper on reconstruction and development, 1994. Notice 1954. 16580. Government Gazette.

- South Africa. (2020). Building a new economy: Highlights of the recovery and reconstruction plan. Government Printing Works.

- South Africa, Department of Finance. (1996). Growth, employment, and redistribution: A macroeconomic strategy. South Africa, Department of Finance.

- South Africa, Department of National Treasury. (2024). Vulindlela operation supporting the implementation of priority structural reforms: Phase 1 review progress in driving economic reform 2020–2024. South Africa, Department of National Treasury.

- South Africa, Department of the Presidency. (2008). Accelerated and shared growth initiative for South Africa: Annual report 2008. South Africa, Department of the Presidency.

- South Africa, Department of the Presidency. (2011). National development plan 2030: Our Future-make it work. South Africa, Department of the Presidency.

- South Africa, Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). (2018). Industrial policy action plan 2018/19–2020/2021: Economic sectors, employment, and infrastructure development cluster. South Africa, Department of Trade and Industry (DTI).

- Stiglingh-Van Wyk, A. (2020). Analyse the implementation of the South African national development plan (NDP). International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanity Studies, 12(2), 352–367. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2011). Rethinking development economics. The World Bank Research Observer, 26(2), 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2018). Where modern macroeconomics went wrong. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 34(1–2), 70–106. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. E., & Rodrik, D. (2024). Rethinking global governance: Cooperation in a world of power. Research Paper. Available online: https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/rethinking_global_governance_06212024.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Strambo, C., Patel, M., & Maimele, S. (2024). Taking stock of the just transition from coal in South Africa. Stockholm Environment Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Streak, J. C. (2004). The gear legacy: Did gear fail or move South Africa forward in development? Development Southern Africa, 21(2), 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulani, T. (2024). Saying YES to opportunities a pathway to opportunity and transformation. BEENgaged Magazine, 2024(2), 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Velelo, L. (2023). Implementing, comprehensiveness and skill provision of the youth employment service (YES) among young black women in Gauteng townships [Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town]. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, H., Tyler, E., Keen, S., & Marquard, A. (2023). Just the transition transaction in South Africa: An innovative way to finance the accelerated phase out of coal and fund social justice. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 13(3), 1228–1251. [Google Scholar]

| Industry | Contribution to GDP | Annual Change in Total Factor Productivity (%) | GDP Growth Acceleration (Percentage Point) | Labour, All Skill Categories | Labour with Primary School Education (Grades 1–7) | Labour with Middle School Education (Grades 8–11) | Labour Completed Secondary School Education (Grade 12) | Labour with Tertiary Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal and social service activities | 16.8% | 5.0 | 1 | −3.7% | −6.8% | −4.3% | −1.9% | −2.3% |

| Transport | 9.7% | 8.4 | 1 | −3.3% | −2.7% | −2.8% | −3.4% | −4.9% |

| Business activities | 8.9% | 15.0 | 1 | −3.1% | −3.8% | −2.9% | −2.6% | −3.5% |

| Electricity and distribution of water | 7.6% | 14.3 | 1 | −3.0% | −3.3% | −2.9% | −2.7% | −3.3% |

| Construction | 5.1% | 11.9 | 1 | −2.9% | −3.0% | −2.8% | −2.7% | −3.6% |

| Financial and insurance | 4.6% | 4.9 | 1 | −2.9% | −2.7% | −2.7% | −2.8% | −3.9% |

| Real estate activities | 4.3% | 13.7 | 1 | −2.9% | −3.4% | −2.8% | −2.4% | −3.3% |

| Post and telecommunications | 3.8% | 46.0 | 1 | −2.8% | −3.4% | −2.8% | −2.4% | −2.9% |

| Agriculture | 2.9% | 21.5 | 1 | −1.9% | −1.2% | −1.7% | −2.0% | −2.9% |

| Mining of coal and lignite | 2.5% | 13.6 | 1 | −1.8% | −2.1% | −1.5% | −1.6% | −2.5% |

| Mining of gold and uranium ore and metal ores | 2.4% | 13.6 | 1 | −1.8% | −2.1% | −1.5% | −1.6% | −2.5% |

| Food industry | 2.0% | 23.7 | 1 | −1.4% | −2.0% | −1.0% | −1.0% | −1.8% |

| Government | 1.8% | 4.8 | 1 | −1.1% | −1.5% | −1.3% | −0.8% | −0.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mabugu, R.E.; Hlongwane, N.W. Modelling South Africa’s Economic Transformation and Growth: A Prospective and Retrospective Analysis. Economies 2025, 13, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070191

Mabugu RE, Hlongwane NW. Modelling South Africa’s Economic Transformation and Growth: A Prospective and Retrospective Analysis. Economies. 2025; 13(7):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070191

Chicago/Turabian StyleMabugu, Ramos Emmanuel, and Nyiko Worship Hlongwane. 2025. "Modelling South Africa’s Economic Transformation and Growth: A Prospective and Retrospective Analysis" Economies 13, no. 7: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070191

APA StyleMabugu, R. E., & Hlongwane, N. W. (2025). Modelling South Africa’s Economic Transformation and Growth: A Prospective and Retrospective Analysis. Economies, 13(7), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070191