Measuring the Innovation Potential of Organizations in Andean Countries and the Applicability of the Capabilities, Results, and Impacts of Innovation Model: A Comparative Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Measuring Innovation in the Andean Context

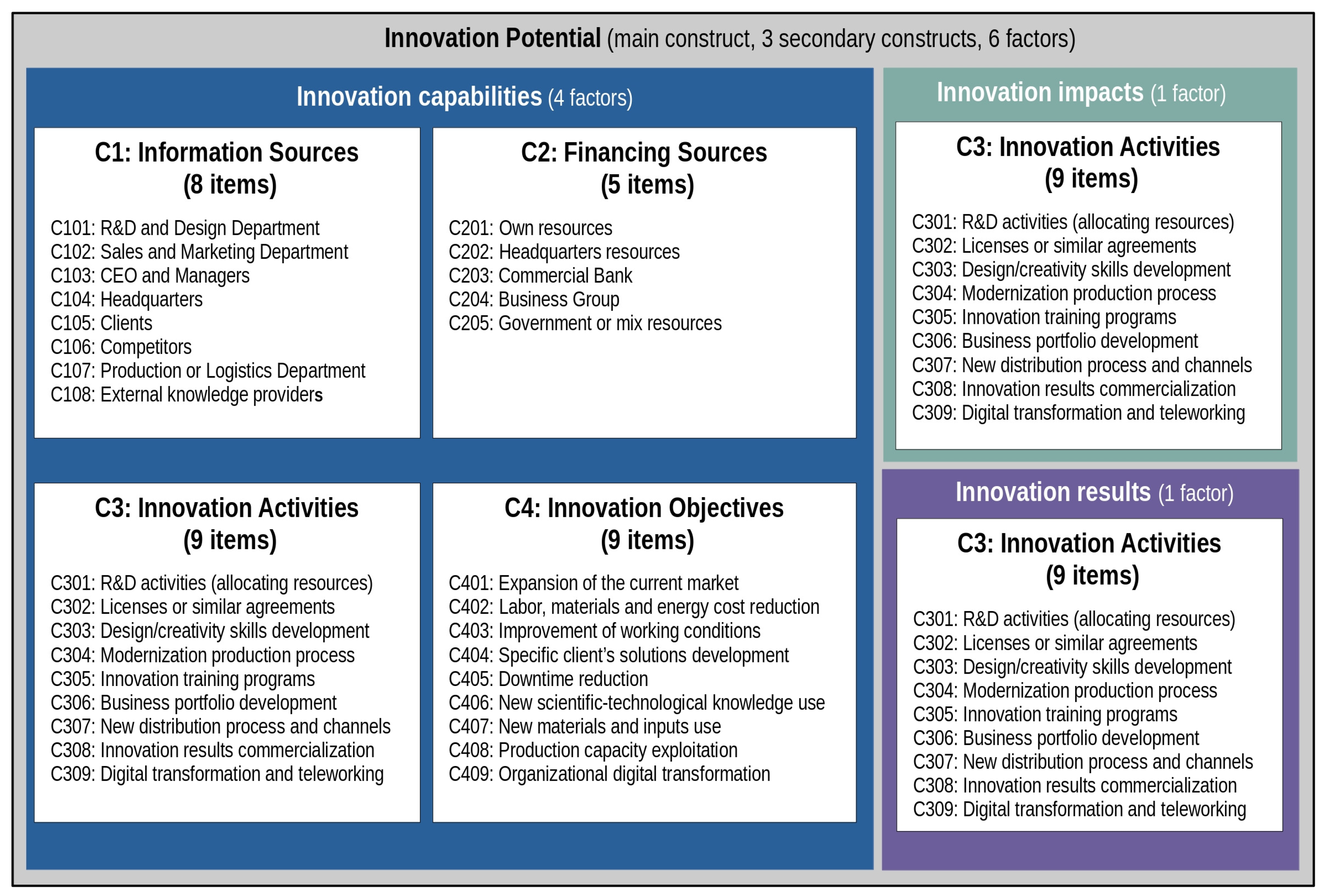

2.2. The CRI Model for Measuring Innovation Potential in Organizations

3. Methodology

3.1. Literature Review

3.2. Selection of Relevant Innovation Measurement Frameworks

3.3. Comparative Analysis for CRI Model Applicability Assessment

4. Results and Discussion

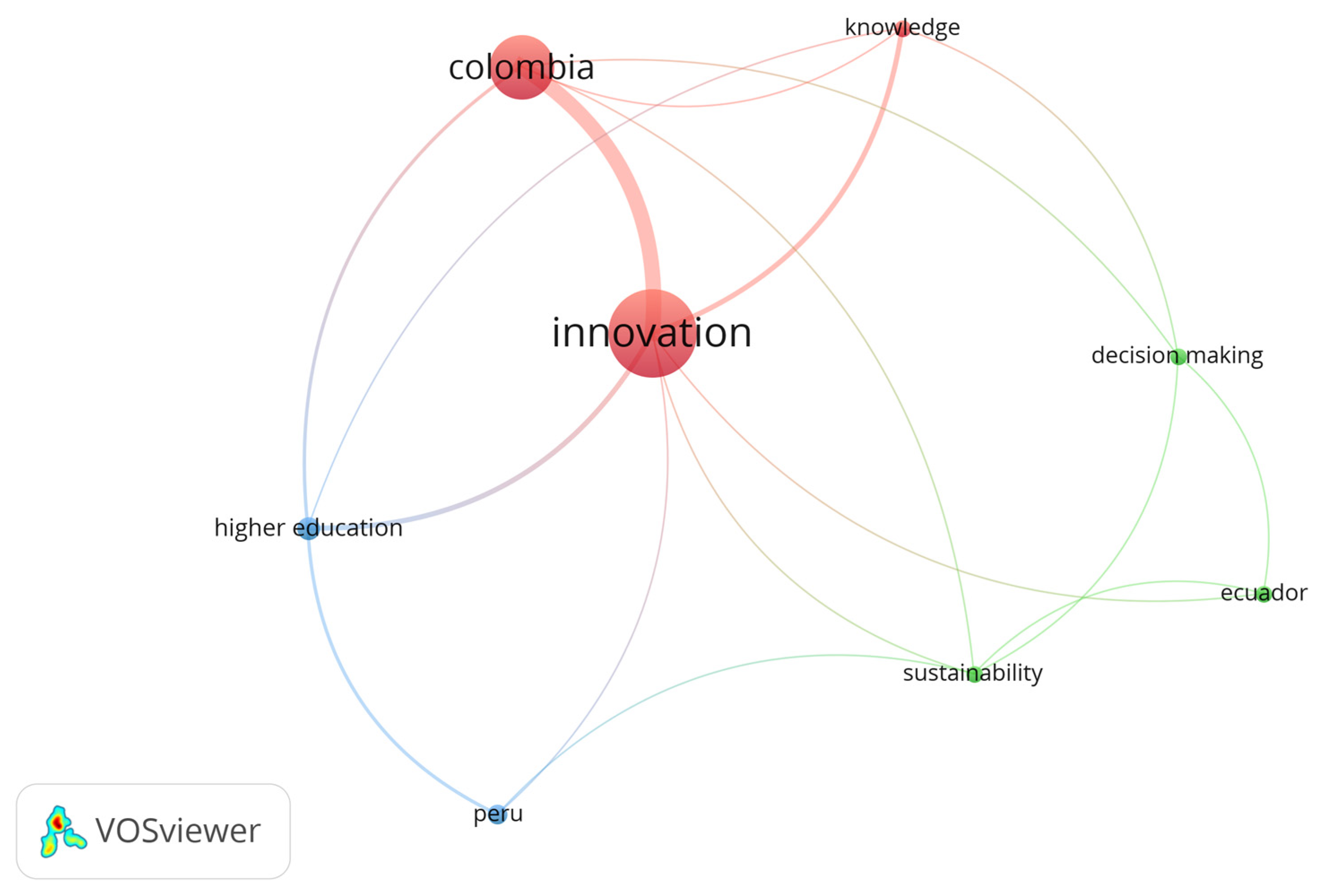

4.1. Bibliometric Analysis

4.2. Evolution of the GII in the CAN

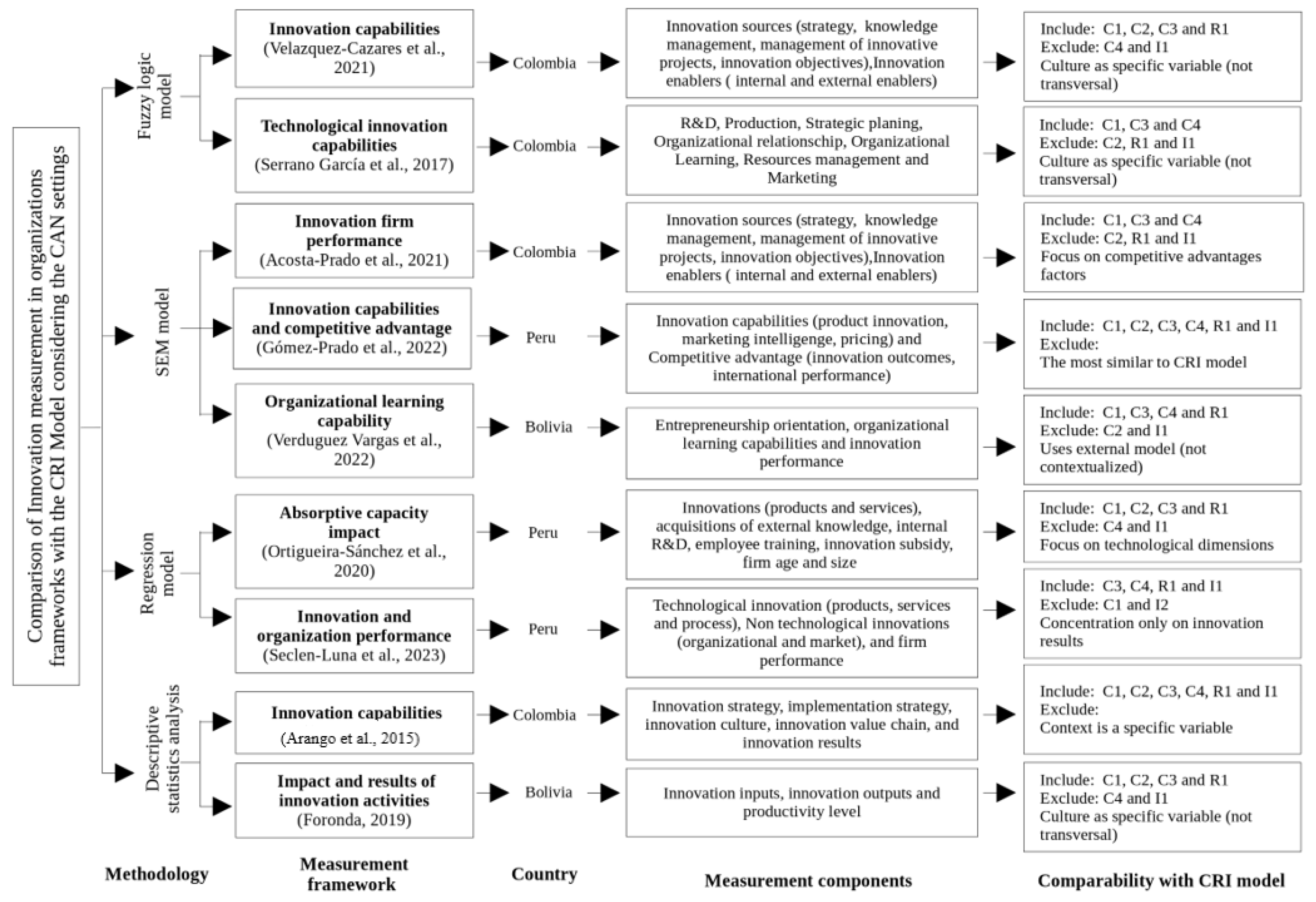

4.3. CRI Applicability Assessment

- The “Measurement Framework” lists the titles of the specific innovation measurement frameworks analyzed, along with the authors and years of publication.

- The “Measurement Components” outlines the key constructs, variables, or dimensions that each framework utilizes to assess innovation. These components represent the aspects that the framework seeks to assess inside an organization’s innovation activities.

- The “Application Sector” indicates the specific industry or organization type for which the respective innovation measurement framework were designed or applied.

- “Similarities with the CRI Model” emphasizes the ways in which the components or focal points of the analyzed frameworks correspond with the constructs of the CRI model (capabilities, results, and impacts). The inclusion of variables pertaining to the factors of information sources (C1), financing sources (C2), innovation activities (C3), innovation objectives (C4), innovation results (R1), and innovation impacts (I1), as delineated in the CRI model, is indicated. This element may also mention broader conceptual similarities.

- “Differences with the CRI Model” details the aspects in which the selected frameworks diverge from the CRI model. Common differences include a lack of evaluation of the CRI model’s factors or a different conceptualization or treatment of culture.

4.3.1. Colombia

4.3.2. Peru

4.3.3. Bolivia

4.3.4. Summary of Key Findings of the CRI’s Applicability Assessment in CAN Countries

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Methodologies Applied in the Selected Measurement Frameworks

5. Final Reflections

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abuelafia, E., Andrian, L. G., Beverinotti, J., Castilleja Vargas, L., Diaz, L. M., Gutiérrez Juárez, P., Manzano, O., & Moreno, K. (2023). Nuevos horizontes de transformación productiva en la región Andina. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Flores, J., Morillo, J., & Shardin, L. (2021). Evolution of innovation indicators in Peru. Revista Gestão Inovação e Tecnologias, 11(3), 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Prado, J. C., Severiche, A. K. R., & Tafur-Mendoza, A. A. (2021). Conditions of knowledge management, innovation capability and firm performance in Colombian NTBFs. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 51(2), 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Bastos, C., & Weber, M. K. (2018). Foresight for shaping national innovation systems in developing economies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 128, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Majali, F. O. (2023). A conceptual framework for operational performance measurement in wholesale organisations. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 72(6), 1627–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, B., Betancourt, J., & Martínez, L. (2015). Implementación de herramientas para el diagnóstico de innovación en una empresa del sector calzado en Colombia. Revista de Administração e Innovação, 12(3), 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandalos, D. (2018). Measurement theory and applications for the social sciences (Vol. 17). The Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-4625-3213-1. [Google Scholar]

- Camio, M., Romero, M., & Álvarez, M. (2014). Nivel de innovación en PYMES del sector software. Revista de Administração FACES Journal, 13, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Carnwell, R., & Daly, W. (2001). Strategies for the construction of a critical review of the literature. Nurse Education in Practice, 1(2), 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres, N., & Urbina, D. (2023). Determinantes de la desigualdad en la Comunidad Andina: Evidencia desde un panel VAR bayesiano. Lecturas de Economía, (99), 209–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, J., & Arias-Pérez, J. (2019). Information technology capabilities and organizational agility. Multinational Business Review, 27(2), 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coral, C. A., Noroña, S., & Pulgar, M. E. (2023). Comunidad andina de naciones, una apuesta por la innovación y la diversificación comercial en Ecuador. Comillas Journal of International Relations, 27, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, E., Meuleman, B., Cieciuch, J., Schmidt, P., & Billiet, J. (2014). Measurement equivalence in cross-national research. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Carpio Gallegos, J. F. D. C., & Miralles, F. (2023). Interrelated effects of technological and non-technological innovation on firm performance in EM—A mediation analysis of Peruvian manufacturing firms. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(8), 1788–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A., Horton, D., Velasco, C., Thiele, G., López, G., Bernet, T., Reinoso, I., & Ordinola, M. (2009). Collective action for market chain innovation in the Andes. Food Policy, 34(1), 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S., Lanvin, B., Rivera León, L., & Wunsch-Vincent, S. (Eds.). (2023). WIPO global innovation index 2023: Innovation in the face of uncertainty. World In-tellectual Property Organization (WIPO). ISBN 78-92-805-3321-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S., Lanvin, B., Rivera León, L., & Wunsch-Vincent, S. (Eds.). (2024). WIPO global innovation index 2024: Unlocking the promise of social entrepreneurship (17th ed.). World Intellectual Property Organization. ISBN 978-92-805-3680-5. [Google Scholar]

- Earl, E. L., De Fuentes, C., Kinder, J., & Schillo, R. S. (2023). Inclusive innovation and how it can be measured in developed and developing countries. In Handbook of innovation indicators and measurement (pp. 297–322). Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-80088-302-4. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Armijos, M., & Valdivia, C. B. (2017). Sustainable innovation to cope with climate change and market variability in the Bolivian Highlands. Innovation and Development, 7(1), 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda, C. (2019). Características y efectos de la innovación en empresas de Bolivia: Una aplicación del modelo CDM. Revista Investigación & Desarrollo, 18(2), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Prado, R., Alvarez-Risco, A., Cuya-Velásquez, B. B., Arias-Meza, M., Campos-Dávalos, N., Juarez-Rojas, L., Anderson-Seminario, M. D. L. M., Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S., & Yáñez, J. A. (2022). Product innovation, market intelligence and pricing capability as a competitive advantage in the international performance of startups: Case of Peru. Sustainability, 14(17), 10703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M., Cheng, C., Elsworth, G. R., & Osborne, R. H. (2020). Translation method is validity evidence for construct equivalence: Analysis of secondary data routinely collected during translations of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Coduras Martínez, A., Guerrero, M., Menipaz, E., Boutaleb, F., Zbierowski, P., Schøtt, T., Sahasranamam, S., & Shay, J. (2023). GEM global entrepreneurship monitor 2022/2023 global report: Adapting to a “new normal”. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-Ayala, A., & Gonzalez-Campo, C. H. (2015). Measurement of knowledge absorptive capacity: An estimated indicator for the manufacturing and service sector in Colombia. Journal of Globalization, Competitiveness, and Governability, 9(2), 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, M., & Hollanders, H. (2020). Innovation indicators: For a critical reflection on their use in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). GRIPS Discussion Papers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, H., Lugones, G., & Salazar, M. (2001). Normalización de indicadores de innovación tecnológica en América latina y el caribe: Manual de bogotá. Colciencias. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, A., Delgado, D., Merino, R., & Argumedo, A. (2022). A decolonial approach to innovation? Building paths towards buen vivir. The Journal of Development Studies, 58(9), 1633–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, K. (2005). Encyclopedia of social measurement (Vol. 2). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmützky, A., Nokkala, T., & Diogo, S. (2020). Between context and comparability: Exploring new solutions for a familiar methodological challenge in qualitative comparative research. Higher Education Quarterly, 74(2), 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhija, M. V., & Karim, S. (2022). A knowledge recombination perspective of innovation: Review and new research directions. Journal of Management, 48(6), 1724–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, V., Robalino-López, A., & Almeida, C. (2023). Medición del potencial de innovación en las organizaciones: Propuesta metodológica para el contexto ecuatoriano. Revista de Gestão e Secretariado (Management and Administrative Professional Review, 14(4), 6149–6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, V., Robalino-López, A., & Almeida, C. (2025a). A comprehensive innovation measurement tool for developing and emerging industrial economies (DEIE): Insight from Ecuador. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, V., Robalino-López, A., & Almeida, C. (2025b). Innovation potential behavior in developing and emerging industrial economies–DEIE: Insight from ICT sector in Ecuador. Management Research: The Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (1995). EUROSTAT Measurement of scientific and technological activities: Manual on the measurement of human resources devoted to S&T—Canberra manual (3rd ed.). OECD. ISBN 978-92-64-06558-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ortigueira-Sánchez, L. C., Stein, W. C., Risco-Martínez, S. L., & Ricalde, M. F. (2020). The impact of absorptive capacity on innovation in Peru. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 15(4), 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego, F. D. l. C. (2021). Human capital and industrialization in Bolivia. Journal of Government and Economics, 3, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, T. Q., Quezada, P. R. Q., Quiñones, A. M. V., & Rojas, G. M. (2022). Integración y desarrollo del comercio intracomunitario de la Comunidad Andina de Naciones. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 28(3), 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero Sepúlveda, I. C. Q., Nieto, Y. O., Parra, D. J. Q., & Cubillos-González, R. (2021). Relación entre capacidad de innovación e índice de innovación en América latina. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 16(3), 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robalino-López, A., Morales, V., Unda, X., & Aniscenko, Z. (2019). Development and innovation processes: Application of a methodology to measure the level of innovation in the Ecuadorian organizational context. Brazilian Journal of Development, 5(6), 4550–4557. [Google Scholar]

- Robalino-López, A., Ramos, V., Franco, A., & Unda, X. (2017). Diseño de un modelo-herramienta para la medición de la innovación en la industria ecuatoriana. CienciAmérica, 6, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Ospina, A., Zuñiga-Collazos, A., & Castillo-Palacio, M. (2024). Factors influencing environmental sustainability performance: A study applied to coffee crops in Colombia. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(3), 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Elena, J. C., Castillo, Y. Y., & Alvarez, I. (2010). Overcoming innovation barriers through collaboration in emerging countries: The case of Colombian manufacturing firms. Industry and Innovation, 30(4), 506–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles-Filho, S. L. M., Avila, A. F., Alonso, J. E. O. S., & Colugnati, F. A. B. (2010). Multidimensional assessment of technology and innovation programs: The impact evaluation of INCAGRO-Peru. Research Evaluation, 19(5), 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seclen-Luna, J. P., Seclen-Luna, J. P., Moya-Fernandez, P., Moya-Fernandez, P., Cancino, C. A., & Cancino, C. A. (2023). Innovation and performance in Peruvian manufacturing firms: Does R&D play a role? RAUSP Management Journal, 58(2), 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano García, J., Acevedo Álvarez, C. A., Castelblanco Gómez, J. M., & Arbeláez Toro, J. J. (2017). Measuring organizational capabilities for technological innovation through a fuzzy inference system. Technology in Society, 50, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S. Y., Kim, D. H., & Jeon, S. Y. (2016). Re-evaluation of global innovation index based on a structural equation model. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 28(4), 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumitra, D., Lanvin, B., & Wunsch-Vincent, S. (Eds.). (2020). WIPO global innovation index 2020: Who will finance innovation? (World Intellectual Proper: S.l.). WIPO. ISBN 978-2-38192-000-9. [Google Scholar]

- Testori, G., & D’Auria, V. (2018). Autonomía and cultural co-design: Exploring the andean minga practice as a basis for enabling design processes. Strategic Design Research Journal, 11(2), 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M., Deng, P., Zhang, Y., & Salmador, M. P. (2018). How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review. Management Decision, 56(5), 1088–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton, G. (2017). Contribution analysis of a Bolivian innovation grant fund: Mixing methods to verify relevance, efficiency and effectiveness. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 9(1), 120–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B., Cayambe, J., Paz, S., Ayerve, K., Heredia-R, M., Torres, E., Luna, M., Toulkeridis, T., & García, A. (2022). Livelihood capitals, income inequality, and the perception of climate change: A case study of small-scale cattle farmers in the Ecuadorian andes. Sustainability, 14(9), 5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursachi, G., Horodnic, I. A., & Zait, A. (2015). How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Economics and Finance, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Cazares, M. G., Gil-Lafuente, A. M., Leon-Castro, E., & Blanco-Mesa, F. (2021). Innovation capabilities measurement using fuzzy methodologies: A colombian SMEs case. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 27(4), 384–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduguez Vargas, V. M., Murillo Mejía, F. R., Verduguez Vargas, V. M., & Murillo Mejía, F. R. (2022). Evaluación del impacto de las capacidades de aprendizaje organizativo y la orientación emprendedora en el desempeño innovador de las empresas bolivianas. Investigación & Desarrollo, 22, 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T. H., Huarng, K., & Huang, D. (2021). Causal complexity analysis of the global innovation index. Journal of Business Research, 137, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description of Selection Criteria | Application in Comparison with CRI Model |

|---|---|

| Contextual relevance: The measurement frameworks are influenced by cultural, socioeconomic, or broader contextual factors. | Allows for the determination of whether alternative models incorporate the socio-cultural context pertinent to the Andean region, which is essential for evaluating the applicability of the CRI model in the CAN. |

| Construct alignment: The theoretical significance of the measurement components within the measurement frameworks aligns with the factors of the CRI model (capabilities, results, impacts). | Facilitates the identification of whether alternative framewoks assess comparable underlying dimensions of innovation potential as the CRI model. |

| Analogous operationalization: The measurement frameworks integrate comparable macro measurement models or exhibit similarities with the components of the CRI model. | Facilitates the evaluation of whether various measurement frameworks employ observable measures comparable with the constructs or concepts included within the CRI model. |

| Methodological rigor and empirical validation: The measurement frameworks clearly delineate the methodologies employed in their development and the processes used for empirical validation. | Indicates the quality and reliability of the measurement attributes of the frameworks being compared to the CRI model. |

| Measurement Framework | Measurement Components | Application Sector | Similarities with the CRI Model | Differences with the CRI Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation capabilities (Velazquez-Cazares et al., 2021) | Innovation sources (strategy, knowledge management, management of innovative projects, innovation objectives); innovation enablers (internal and external enablers) | Agriculture | Model particularities Considers innovation capabilities to be essential for business innovation. CRI model factor inclusion Includes specific variables related to information sources (C1), innovation activities (C3), financing sources (C2), and innovation results (R1). | Model particularities Includes culture as a separate factor and not transversally like the CRI model. Defines “innovation objectives” differently, focusing on the types of innovation outputs (results). Differentiates resources into financial and other kinds. CRI model factor inclusion Does not evaluate innovation objectives (C4) or innovation impacts (I1). |

| Technological innovation capabilities (Serrano García et al., 2017) | R&D, production, strategic planning, organizational relationship, organizational learning, resources management, and marketing | ICT services in academic institutions | Model particularities Organizational innovation capabilities are seen as inputs for innovation. CRI model factor inclusion Include some variables related to information sources (C1), innovation activities (C3), and innovation objectives (C4). | Model particularities Includes culture as a specific variable and not transversally like the CRI model. CRI model factor inclusion Does not evaluate the results (R1) and impacts (I1) of innovation as outputs of innovation. |

| Innovation firm performance (Acosta-Prado et al., 2021) | Innovation capabilities and knowledge management | New Technology-based Firms (NTBFs) | Model particularities Framework design includes micro-environment (internal environment) and macro-environment (competitive environment). CRI model factor inclusion Includes variables related to information sources (C1), innovation objectives (C4), and innovation activities (C3). | Model particularities Focuses on factors that gives competitive advantages. CRI model factor inclusion Does not evaluate financing sources (C2), innovation results (R1), and innovation impacts (I1). |

| Innovation capabilities (Arango et al., 2015) | Innovation strategy, implementation strategy, innovation culture, innovation value chain, and innovation results | Manufacturing | Model particularities Considers innovation capabilities to be determinants of innovation performance measured through their innovation results (tangible consequences of innovation processes). CRI model factor inclusion Includes some variables related to innovation activities (C3), innovation objectives (C4), and innovation results (R1) | Model particularities Includes culture as a specific variable and not transversally like the CRI model. CRI model factor inclusion Does not evaluate information sources (C1), financing sources (C2), and innovation impacts (I1). |

| Measurement Framework | Measurement Components | Application Sector | Similarities with the CRI Model | Differences with the CRI Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Absorptive capacity impact” (Ortigueira-Sánchez et al., 2020) | Innovations (products, services, etc.), acquisition of external knowledge, internal R&D, employee training, innovation subsidy, firm age and firm size | Manufacturing and services | Model particularities Also evaluates innovation perception, specifically emphasizing management viewpoints on the capacity to assimilate innovation. CRI model factor inclusion Include several variables related to information sources (C1), financing sources (C2), innovation activities (C3), and innovation results (R1). | Model particularities Focuses on technological dimensions of innovation absorption rather than overall innovation potential. CRI model factor inclusion Lacks analysis of innovation objectives (C4) and innovation impacts (I1). |

| “Innovation and organization performance” (Seclen-Luna et al., 2023) | Technological innovations (products, services and process), non-technological innovations (organizational and market), and firm performance | Manufacturing and KIBSs (Knowledge-Intensive Business Services) | Model particularities Analyzes innovation results as innovation outputs. CRI model factor inclusion Includes, particularly, variables related to innovation results (R1) and some variables related to innovation activities (C3) and innovation objectives (C4), and only the economic dimension of innovation impacts (I1). | Model particularities Concentrates only on innovation results and lacks an analysis of innovation capabilities. CRI model factor inclusion Does not evaluate information sources (C1) and financing sources (C2). |

| “Innovation capabilities and competitive advantage” (Gómez-Prado et al., 2022) | Product innovation, marketing intelligence, and pricing (innovation capabilities), and competitive advantage and international performance (innovation outcomes) | Active startups in manufacturing (food, beauty products, beverages) | Model particularities The macro measurement model is comparable to the CRI model. CRI model factor inclusion Includes variables related to all factors of innovation capabilities (C1, C2, C3, and C4) and includes some variables similar to innovation results (R1) and impacts (I1). | Model particularities The macro measurement model is comparable with the CRI, in that is examines three innovation capabilities (product innovation, marketing intelligence, and pricing capability) as determinants of innovation outcomes (competitive advantage and international performance). CRI model factor inclusion Focuses on innovation capabilities and outcomes related to competitive innovation and organizational performance. |

| Measurement Framework | Measurement Components | Application Sector | Similarities with the CRI Model | Differences with the CRI Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational learning capability (Verduguez Vargas et al., 2022) | Entrepreneurship orientation and innovation performance | Multi-sectoral mix | Model particularities Recognized the influences of certain organizational learning capabilities (innovation inputs) on innovation performance (innovation outcomes). CRI model factor inclusion Certain variables resemble those incorporated in the CRI model, such as innovation capabilities (C1, C2, C3, C4), innovation results (R1), and innovation impact (I1). | Model particularities Treats innovation performance as a secondary outcome, not the central focus of measurement. The innovation environment (context) is included as a variable, while in the CRI model, it is addressed transversally. CRI model factors inclusion The focus of the variables is on innovation performance and entrepreneurial orientation. |

| Impact and Results of Innovation Activities (Foronda, 2019) | Innovation inputs, innovation outputs, and productivity | Manufacturing and services | Model particularities Focusing on innovation activities and innovation objectives as inputs to evaluate labor productivity in innovation processes. CRI model factor inclusion Incorporates certain variables in innovation inputs related to innovation activities (C3), innovation objectives (C4), information sources (C1), and innovation results (R1). | Model particularities Lacks a comprehensive framework for assessing innovation impacts. Does not considerate the incorporation of contextual analysis. CRI model factor inclusion Does not explicitly consider information sources (C1) or innovation impacts (I1). Does not delineate variables for financing sources (C2), although it incorporates certain features of innovation financing in a transversal manner. |

| Country | Key Findings of Innovation Measurement Frameworks Compared to CRI Model |

|---|---|

| Colombia | Acknowledge innovation capabilities (C1, C2, C3, and C4) and results (R1) as key drivers of innovation. Lack comprehensive evaluation of innovation results (R1) and innovation impacts (I1). Treat culture differently than the CRI model’s transversal approach (usually as a separate variable). |

| Perú | Emphasize importance of innovation capabilities (C1, C2, C3, and C4) for achieving innovation results (R1). Align with CRI model factors (C1, C2, C3, and C4). Focus on innovation capabilities (particularly in innovation activities (C3) and innovation results (R1)). Limited analysis of innovation impacts (I1). Present a comprehensive macro-conceptual model similar to the CRI model. |

| Bolivia | Limited focus on innovation capabilities (C1, C2, C3, and C4) as determinants of innovation results (R1). Lack thorough assessment of innovation impacts (I1) and consideration of all CRI model factors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morales, V.; Robalino-López, A. Measuring the Innovation Potential of Organizations in Andean Countries and the Applicability of the Capabilities, Results, and Impacts of Innovation Model: A Comparative Approach. Economies 2025, 13, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050133

Morales V, Robalino-López A. Measuring the Innovation Potential of Organizations in Andean Countries and the Applicability of the Capabilities, Results, and Impacts of Innovation Model: A Comparative Approach. Economies. 2025; 13(5):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050133

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorales, Verónica, and Andrés Robalino-López. 2025. "Measuring the Innovation Potential of Organizations in Andean Countries and the Applicability of the Capabilities, Results, and Impacts of Innovation Model: A Comparative Approach" Economies 13, no. 5: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050133

APA StyleMorales, V., & Robalino-López, A. (2025). Measuring the Innovation Potential of Organizations in Andean Countries and the Applicability of the Capabilities, Results, and Impacts of Innovation Model: A Comparative Approach. Economies, 13(5), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050133