Abstract

In this study, we provide the first estimates of the effect of COVID-19 (COVID-19 legal restrictions) on catastrophic medical expenditure and forgone medical care in Africa. Data for this study were drawn from the 2018/19 Nigeria General Household Survey (NGHS) panel and the 2020/21 Nigeria COVID-19 National Longitudinal Phone Survey panel (COVID-19 NLPS). The 2020/21 COVID-19 panel survey sample was drawn from the 2018/19 NGHS panel sample monitoring the same households. Hence, we leveraged a rich set of pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 panel household surveys that can be merged to track the effect of the pandemic on welfare outcomes. We found that the COVID-19 legal restrictions decreased catastrophic medical expenditure (measured by out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures exceeding 10% of total household expenditure). However, the COVID-19 legal restrictions increased the incidences of forgone medical care. The results showed a consistent positive effect on forgone medical care across waves one and two, corresponding to full and partial implementation of COVID-19 legal restrictions, respectively. However, the negative effect on catastrophic medical spending was only observed when the COVID-19 legal restrictions were fully in force, but the sign reversed when the restriction enforcement became partial. Moreover, our panel regression analyses revealed that having health insurance is associated with a reduced probability of incurring CHE and forgoing medical care relative to having no health insurance. We suggest that better policy design in terms of expanding the depth and coverage of health insurance will broaden access to quality healthcare services during and beyond the pandemic periods.

JEL Codes:

I12; I13; I14; I18

1. Introduction

Attaining access to needed medical care for all people without exposure to financial hardship (universal health coverage (UHC)), through adequate financial protection, has been a subject of intense debate among health academics and policymakers in developing and developed countries. Policy debates on ways to reach UHC have always focused on the mobilization of resources for healthcare, shifting from direct healthcare financing to third-party mechanisms (such as government and health insurance financing). The latter mechanisms are noted to help curb issues of catastrophic out-of-pocket (OOP) medical expenditures and ensure that households do not forgo healthcare needs due to lack of income (WHO, 2017).

In African countries, including Nigeria, resource mobilization for the health system to attain UHC remains limited. Since the deregulation process of the 1980s, the Nigerian health system has witnessed the dominance of private healthcare suppliers, reliance on OOP medical financing mechanisms, and the introduction of user charges in public healthcare facilities. These have shifted a greater financial burden onto households, leading to households forgoing medical care and worsening public health status (Ichoku, 2005). In Nigeria, where most households rely on OOP medical spending, the COVID-19 pandemic has hampered livelihood sources, exposing the vulnerabilities in the country’s healthcare system. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Nigeria’s government hospitals faced significant structural and systemic challenges, including inadequate infrastructure, insufficient funding, and a shortage of healthcare professionals (Obi-Ani et al., 2021). Public healthcare facilities were often underfunded, with government health expenditure accounting for only about 3% of the GDP, far below the 15% Abuja Declaration target (World Bank, 2021b). The National Health Act of 2014 sought to improve funding through the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), but implementation remained slow, leading to persistent disparities in healthcare access (Igbokwe et al., 2024).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, these weaknesses became more apparent as government hospitals struggled with a surge in patient demand, overburdened healthcare facilities, limited intensive care unit (ICU) capacity, and shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators (Ohia et al., 2020). Although the government allocated emergency funds and established isolation centers, delays in funding disbursement and poor coordination hindered response efforts (Aregbeshola & Folayan, 2022). This lack of preparedness highlights structural healthcare system weaknesses—posing risks to the levels of catastrophic medical spending and forgone medical care. Empirical evidence on the effect of COVID-19 on catastrophic medical spending and forgone medical care is needed to enable better policy design to tackle the health financing effect of COVID-19 and guard the welfare of households against such pandemics in the future.

Achieving UHC requires countries to fund their health systems through general government revenues or premium contributions to social health insurance complemented with government revenues (WHO, 2005, 2010, 2017). These financing approaches enable the mobilization of sustainable, substantial resources for health. They create large risk pools with more financial security and a higher potential to contribute to households’ wider access to healthcare services (McIntyre, 2007). However, government funding for health in Nigeria remains generally inadequate, whereas OOP medical spending in the country remains alarmingly high (Ataguba et al., 2022). OOP payment as a proportion of total medical and gross private medical expenditure in Nigeria is still above 70% and 90%, respectively (World Bank, 2021b). Nigeria is still far below the UHC health insurance financing target of 90%, as its health insurance contribution to total health expenditure (THE) remains at an average of only 2% (Nigeria Ministry of Health, 2021). Moreover, the total government budgetary allocation to the health sector has remained persistently low, at an average of about 5%, against the international benchmark of 15%. Government health spending as a percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) has remained roughly 3% against the 7% recommended level, implying that OOP medical payment is the dominant health financing system in Nigeria (World Bank, 2021b).

Many Nigerian households still suffer financial hardship resulting from high OOP medical spending (Edeh, 2022). The problem here is that high OOP medical spending leaves households with two unpleasant options—sacrifice basic living standards to attain needed medical care or maintain basic living standards to forgo needed medical care (Gabani & Guinness, 2019). This problem could worsen when households lose income, implying that the magnitudes of catastrophic medical spending and forgone medical care are likely determined by the level of income (Jung et al., 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic had profound economic and social implications globally due to variations in imposed restrictions and lockdowns. Despite facing relatively much lower numbers of infections and deaths related to COVID-19, low- and middle-income countries have nonetheless faced more economic losses (Mascagni & Santoro, 2021). The effect of COVID-19 on the already struggling economies of sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries is expected to be considerably higher (OECD, 2020). Although governments introduced measures to combat it (like lockdowns to slow and reverse the trend of spread), these measures pose internal shocks likely to slow down and dampen growth and reduce household income (Yimer et al., 2020). Nigeria’s economy was among those that contracted following the COVID-19 pandemic. One in five small businesses risked total collapse, while over 50% of all small businesses were negatively affected by COVID-19 (International Trade Centre, 2020). The collapse of small businesses implies loss of income for many households who were restricted from engaging in work activities within this period. Loss of household income can create an economic burden, harming the household financially. This could lead to catastrophic health spending or forgone medical care (Jung et al., 2021).

There has been a proliferation of studies in the health economics literature examining the incidence of catastrophic health spending (CHE) in pre-COVID-19 periods (Aregbeshola & Khan, 2018; Kwesiga et al., 2020; Edeh, 2022; among others) and in COVID-19 periods (Eze et al., 2022; Ahmed et al., 2022; Ogundare et al., 2022; Getachew et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023; Matebie et al., 2024). However, these studies have not examined the CHE effect of an income/health shock variable like COVID-19. If households face an income/health shock, the risk of CHE could become more severe (Jung et al., 2021). We bring novelty by quantitatively assessing the effect of COVID-19 on catastrophic medical spending. This study contributes to the health financing literature by giving new insights into the causes of CHE, focusing specifically on the effect of COVID-19. In contrast, many existing studies interpret the incidence of CHE in the absence of COVID-19 shock. The work of Jung et al. (2021) examined the effect of income loss on CHE in Korea but in the absence of COVID-19 shock. Studies relating COVID-19 to CHE mainly exist for countries in Europe, Southern/Northern America, and Asia (Garg et al., 2022; Haakenstand et al., 2023; Rajalakshmi et al., 2023; Zavras & Chletsos, 2023). Our study examines the effect of COVID-19 on CHE in Africa, using Nigeria—the largest economy in Africa—as a case study.

In Africa, comparative knowledge on catastrophic care and forgone care remains scarce pre-COVID-19 and even more scarce in the COVID-19 pandemic period. In terms of forgone medical care incidence, studies have also been limited during both the pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods. While some studies (Mielck et al., 2009; Bremer, 2014, among others) have been conducted in countries outside Africa, very few studies (Gabani & Guinness, 2019) exist in African countries pre-COVID-19. During the COVID-19 period, several studies on medical care access were conducted in countries outside Africa (Lange et al., 2020; Cantor et al., 2022); however, few studies (Kakietek et al., 2022) exist for Africa. The work of Kakietek et al. (2022) is an aggregate analysis masking individual country differences. To attempt to fill this knowledge gap, we further contribute to the literature by examining the effect of COVID-19 on forgone medical care incidence. This is an issue that has scarcely been studied in Africa. When needed healthcare services are not affordable, a household is unable to spend money on them and forgoes them (Gabani & Guinness, 2019). COVID-19 has decreased income, thus reducing resources available for households to purchase medical care and resulting in forgone healthcare services. Households that cannot afford healthcare services do not incur CHE but face a lower quality of life due to untreated health issues. If certain households do not incur CHE but forgo healthcare due to an inability to purchase it, then financial hardship due to healthcare payment is underestimated (Pradhan & Prescott, 2002).

This study is important for understanding how COVID-19 lockdown policies impacted out-of-pocket (OOP) medical spending, a critical issue in Nigeria, where healthcare financing heavily relies on direct household payments (Edeh, 2022). While prior studies have often focused on high-income settings, our study provides novel evidence from a lower–middle-income context, showing that COVID-19 legal restrictions significantly reduced OOP medical spending—not due to improved affordability but because income loss forced households to forgo needed care (Abor & Abor, 2020). This decline in OOP spending, accompanied by a rise in forgone care, highlights a hidden consequence of the pandemic: financial hardship limited healthcare access, particularly for poorer households, rural dwellers, and those without health insurance (Tandon et al., 2020). These findings underscore the urgent need for policy interventions, such as expanding health insurance coverage and implementing emergency healthcare subsidies to safeguard access to essential medical services during crises and beyond.

This study, therefore, aims to achieve the following objectives: First, it investigates the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic financially impacted Nigerian households by pushing their OOP medical spending below a given income (measured with expenditure) threshold. Second, it examines the degree to which Nigerian households relinquished necessary medical care following reduced income during the COVID-19 pandemic. These objectives are achieved using a logit model, considering that COVID-19 and its corresponding lockdown measures are exogenous to the household. Moreover, the logit model is combined with the standard techniques used in the computation of incidences of catastrophic medical spending and forgone medical care. The data used pertain to Nigeria’s most recent General Household Survey (GHS) for 2018/19 and Nigeria’s COVID-19 phone survey for 2020/21. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The next section describes the methodology and datasets, Section 3 presents and analyzes the findings, and Section 4 provides a summary of the findings and discusses policy implications.

2. Methods and Data

2.1. Framework

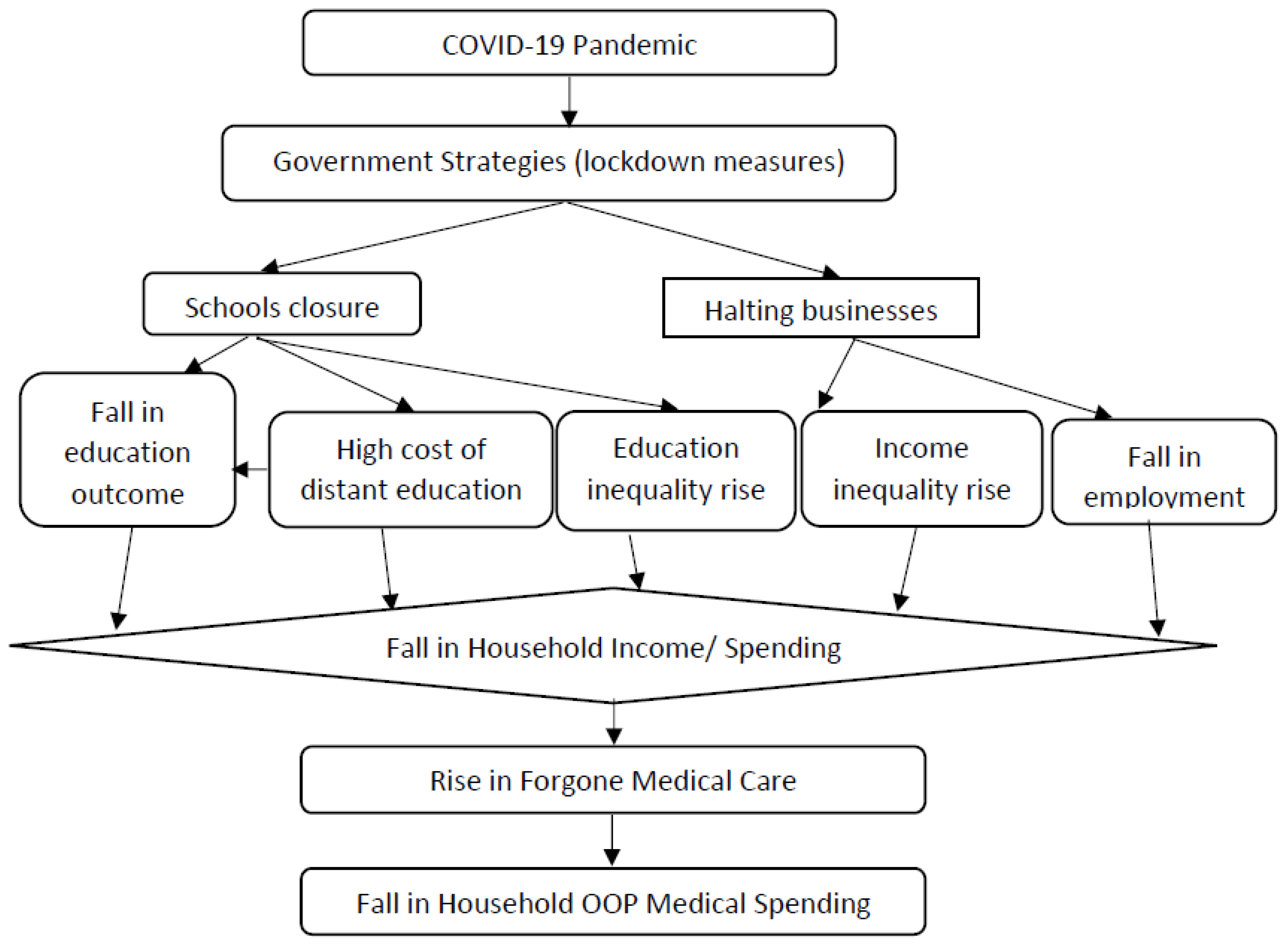

Given our interest in the effect of COVID-19 (specifically measured by the COVID-19 legal restrictions) on CHE and forgone medical care, we adapted a framework that links COVID-19 to both forgone medical care and OOP medical expenditure through a decrease in household income, as seen in (Tandon et al., 2020; BIN et al., 2020). Through the government-imposed lockdown measures, COVID-19 resulted in the closure of schools and businesses. The closure of schools increased the cost of distance learning, while the closure of businesses led to a decline in employment and worsened schooling outcomes, both of which are expected to reduce household income. A decline in household income implies a lack of money, which increases forgone medical care but may reduce catastrophic health expenditures (Tandon et al., 2020; Kakietek et al., 2022). The pathways through which COVID-19 affects forgone medical care and OOP medical expenditure due to a decrease in household income are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 and household medical spending mechanisms. Source: Adapted from (Tandon et al., 2020; BIN et al., 2020).

We used Nigeria’s COVID-19 survey to identify households affected by COVID-19 legal restrictions. We then utilized both Nigeria’s pre-COVID-19 survey (General Household Survey (GHS)) and the COVID-19 survey to identify households not affected by the COVID-19 legal restrictions. Notably, both datasets are panel surveys tracking the same households, allowing them to be merged. Since the 2018/19 GHS panel served as the sampling frame for the 2020/21 Nigeria COVID-19 National Longitudinal Phone Survey (NLPS), the two datasets can be linked (see Section 2.4 for more details). Using the COVID-19 survey, we merged responses from three questions (6, 8a, and 17 from the questionnaire) related to a ‘COVID-19 legal restriction’. The survey defines COVID-19 legal restrictions as situations where offices were closed or individuals had no access to workplaces due to government-imposed regulations. Specifically, the questionnaire asks, “What was the main reason you stopped working?” Households selecting “COVID-19 legal restriction” (Option 1) were coded as 1, while those selecting other reasons were coded as 0. We merged these responses because the questionnaire posed similar questions, “What was the main reason you stopped working?” and “Why were you unable to work?”, and different households answered them. Using only one question would have excluded some households affected by the COVID-19 legal restrictions.

Note that in the COVID-19 survey, there is no separate variable to identify households affected solely by COVID-19 infections or, for instance, households’ COVID-19-related spending on face masks, sanitizers, etc. The identification in the survey is based on households affected by COVID-19 legal restrictions/lockdowns (legal restrictions due to COVID-19). Hence, the effect we measured in this study is that of the COVID-19 legal restriction/COVID-19 lockdown policy, as indicated in the survey. However, we do not completely rule out the possibility of a separate COVID-19 infection effect on CHE. Based on the survey data available to us, we are unable to measure the effect of COVID-19 infections alone on CHE. We are only able to measure in this study (using available data) the effect of COVID-19 legal restrictions/legal restrictions due to COVID-19 on CHE, which is equivalent to the effect of the COVID-19 lockdown policy.

2.2. Descriptive Statistical Analysis Using Mean and Percentage Distribution Techniques

The results in Table 1 were generated using descriptive statistics, specifically through the computation of means, standard deviations, and minimum–maximum values of key variables used in the analysis. The analysis in Table 2 and Table 3 also employs descriptive methods, comprising proportion estimates to examine the prevalence of CHE and forgone medical care. The results in Table 4 and Table 5 were derived from descriptive statistical techniques, specifically through the computation of mean values and percentage distributions to examine household expenditure patterns. Table 4 uses mean analysis to calculate average household expenditures on medical care, food, and non-food items across different demographic and economic groups. Table 5, on the other hand, utilizes percentage distribution analysis to express each expenditure category as a share of total household spending. These statistical techniques are instrumental in identifying economic inequalities and informing policy measures aimed at improving healthcare affordability and financial protection for vulnerable populations.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 2.

CHE prevalence defined by different thresholds in the pre-COVID-19 period, 2019.

Table 3.

Prevalence of forgone care and reasons for forgoing care in the COVID-19 period.

Table 4.

Mean monthly household medical expenditures, total expenditures, food expenditures, and non-food expenditures (Naira).

Table 5.

Percent shares of medical, food, and non-food expenditures to total household expenditures.

2.3. Standard Approaches to the Computation of CHE and Forgone Medical Care and the Measurement of the Effect of COVID-19

2.3.1. CHE Incidence

A household is deemed to have experienced CHE when its out-of-pocket (OOP) medical spending as a share of income (measured by expenditure) exceeds a given threshold value. As in the related literature (Xu et al., 2003; Kien et al., 2016), the current study computes CHE as medical spending that exceeds 10% of the household’s total expenditure using a binary variable. There is still no consensus on a given threshold value for the computation of CHE (Xu et al., 2007; Leive, 2008). Hence, to have a broader picture of CHE incidence, this study defines CHE using other threshold budget shares, i.e., 25% of total household expenditure and the WHO threshold of 40% of non-food expenditure, i.e., household remaining income after basic subsistence needs have been met (Gu et al., 2017). Using the non-WHO definition, for instance, the corresponding OOP share is calculated by computing the ratio of OOP payments to a household’s expenditure, as stated below:

The CHE is computed as a binary variable that takes the value 1 if a household incurs CHE and 0 otherwise. For any given threshold , say 10% for the current study, the CHE would be obtained as follows:

2.3.2. Effect of COVID-19 Legal Restrictions or COVID-19 Lockdown Policy on CHE

Having established the threshold for household out-of-pocket expenditure to be catastrophic, the next step is to estimate the effect of COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE. Following Equation (2), we have a dichotomous dependent variable (CHE); thus, a binary response model is applied. Although the logit and the probit are binary response models and produce similar results, there are some differences between them, especially in the functional formats. While the logit model follows a logistic distribution, the probit model follows a normal distribution (Wooldridge, 2013). However, we focused on the logit as the main model in the paper. The choice of logit over probit is informed by the non-normal distribution of the residuals of the initially estimated probit models. Although we have estimated a cross-sectional logit, we have mainly focused on the panel logit in drawing conclusions since it has the advantage of not only studying the dynamics of change but also making causal inferences (Greene, 2010). In our panel data, the cross-sectional unit (i) represents individual households, which are tracked over multiple time periods (t). The panel data follow a wave-based time structure, where (t) represents different survey rounds conducted in January–February 2019 (pre-COVID-19 period), April–May 2020 (lockdown phase), and June–July 2020 (partial reopening phase). This panel structure allows us to examine the dynamic effects of COVID-19 restrictions on catastrophic medical spending and forgone care.

There are several common panel estimation approaches, including the fixed effect and the random effect. The key challenge with the fixed effect approach is that the time-invariant regressors (e.g., gender) are eliminated or not clearly identified in the process of differencing. Hence, we have chosen the random effect approach since it does not involve a lack of identification or elimination of time-invariant regressors. Although it assumes the presence of unobserved individual heterogeneity, our key regressor, the COVID-19 lockdown policy, is exogenous to the household.

Following Gujarati and Porter (2009), we started by expressing the probability of incurring CHE as follows:

where represents a vector of appropriate controls that includes COVID-19, the key variable of interest. COVID-19 here is a dummy variable for COVID-19 legal restrictions that takes the value 1 for households affected by the government’s COVID-19 lockdown measures and 0 otherwise. is the vector of estimated parameters. Z drives the changes in , the outcome of catastrophic medical spending, which takes the value 1 if the household incurs CHE and 0 otherwise. We acknowledge that the coefficient on COVID-19 is not the effect of COVID-19 infections but the effect of COVID-19 plus measures implemented by the government during the period to deal with the pandemic. We recognize that both COVID-19 and the COVID-19 policy measures taken by the government were exogenous to households and define the COVID-19 variable as households affected by the COVID-19 legal restrictions, as indicated in the COVID-19 survey. We then ran a regression of the CHE dummy on the COVID-19 legal restrictions dummy plus controls.

2.3.3. Forgone Medical Care Incidence

To account for and measure forgone medical care (FMC) incidence, previous studies (e.g., Gabani & Guinness, 2019) have employed a simplified needs-based approach. Initially, we intended to follow the method in Gabani and Guinness (2019) to measure forgone healthcare incidence as the proportion of households that experienced a health shock, had not incurred CHE, and also had not spent more than a specified threshold value (minimum medical expenditure, e.g., medical spending on a basic blood test) in OOP medical payments. However, the challenge of using this method lies in selecting the appropriate threshold value for OOP medical payments. Hence, in this study, we used a clearer variable employed in most of the previous literature (e.g., Kakietek et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2022) as household forgone healthcare, which we obtained from the COVID-19 survey. In the COVID-19 survey, the following questions are asked:

Have you or any member of your household needed medical treatment since mid-March? Were you or the member of your household able to access the medical treatment? What was the reason you or the member of your household were not able to access the medical treatment? [no money?, no medical personnel available?, due to movement restriction?, others?]. In line with the previous related literature (Kakietek et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2022), we define forgone care as households that reported needing medical care but were unable to access it because of a lack of money or due to high costs. In other words, forgone care is defined as the percentage of households that needed care but could not afford it. This definition of forgone care due to financial reasons is justified, as the study focuses on health financing. Additionally, previous studies (e.g., Kakietek et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2022) have acknowledged this definition of forgone care due to financial constraints. However, to enable comparison, we also define forgone care for any other reason (such as due to COVID-19, a lack of medical supplies, or other reasons) aside from financial constraints.

2.3.4. Effect of COVID-19 Legal Restrictions on Forgone Medical Care Incidence

To estimate the effect of COVID-19 legal restrictions on forgone medical care (FMC), we followed the logit expressions above and replaced CHE with the outcome variable, FMC. We started by expressing the probability of forgoing medical care as follows:

where represents a vector of appropriate controls that includes COVID-19, the key variable of interest already defined above, and is the vector of parameters to be estimated. Z drives the change in FMC, the observed outcome of forgone medical care, which takes a value of 1 if a household has forgone care and 0 otherwise.

2.4. Datasets

Data for this study were drawn from the 2018/19 period (wave 4) of the nationally representative Nigerian General Household Surveys (NGHS). The 2018/19 NGHS is representative of the 36 states in Nigeria and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja, with sampling covering around 4976 households. This was supplemented with the Nigeria COVID-19 National Longitudinal Phone Survey panel (COVID-19 NLPS) conducted in 2020–2021. Among the 4976 households interviewed in the 2018/19 NGHS panel, 4934 (99.2%) provided at least one phone number. For the COVID-19 NLPS, 3000 households were sampled from the frame of 4934 households with contact details in the 2018/19 NGHS panel. Since the 2018/19 NGHS panel served as the frame for the Nigeria COVID-19 NLPS, the COVID-19 NLPS datasets can be merged with the NGHS panel datasets. The household’s unique key variable (hhid) was used to merge the household type datasets, and the individual’s unique key variables (hhid and indiv) were used to merge any individual type files (Basic Information Document (BID) from the Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics (NBS, 2021)).

In the first wave of the COVID-19 survey, 3000 households were contacted from the 2018/19 NGHS panel, which originally included 4934 households that had provided contact details. However, only 1950 households were successfully interviewed in wave one, serving as the total sample size for the wave one analysis. In terms of regional distribution, 1195 and 947 households were fully interviewed in rural and northern areas, respectively, while 755 and 1003 were interviewed in the urban and southern areas, respectively (COVID-19 NLPS Report, 2020). For the second wave, all 1950 households from the first wave were contacted, but only 1820 were successfully interviewed, making 1820 the total sample size for the wave two analysis. The regional distribution for wave two includes 1103 households interviewed in rural areas and 904 in the northern zone, whereas 717 households were interviewed in urban areas and 916 in the southern zone. Note that the zonal distribution of the data consists of two major regional divisions in Nigeria. The southern zone comprises the South-East, South-West, and South-South regions, while the northern zone includes the North-East, North-West, and North-Central regions. Hence, no specific zone was excluded from the analyses. For the panel data, we combined the fully interviewed households from both waves, resulting in a total panel sample size of 3770 households (COVID-19 NLPS Report, 2020).

The survey covers a wide range of socio-economic topics, which are collected through three different questionnaires: the Household Questionnaire, the Agriculture Questionnaire, and the Community Questionnaire. This study drew information from the Household Questionnaire, which provides information on demographics, education, health, labor, time use, food and non-food expenditure, household non-farm income-generating activities, food security and shocks, safety nets, housing conditions, assets, and other sources of household income (NBS, 2019). The survey was produced by the NBS in collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the National Food Reserve Agency, and the World Bank, with financial support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (NBS, 2019).

3. Findings

3.1. Summary Statistics

This subsection presents the summary statistics of the full panel sample of the study in terms of the mean values and the corresponding standard deviations. As seen in Table 1 above, roughly 41% of the panel’s sampled households, on average, incur CHE. On average, 10% and roughly 13% of sampled households forgo medical care due to financial constraints and due to any reason, respectively. Forgone care due to any reason is defined as medical care forgone because of financial difficulties, fear of contracting COVID-19, or a lack of medical supplies. On average, 51%1 of households were affected by COVID-19 (i.e., had no access to their workplaces) due to government-imposed lockdown measures. The 49% proportion of female-headed households suggests a roughly balanced gender distribution in the study. This balanced distribution is also evident across the northern and southern zones of the country. However, the rural–urban composition is skewed toward rural areas, which account for 61% of the total sample. There is a slight difference between the proportion of households in the second-lowest economic status and those in the highest economic status. In the second-lowest economic category, households make up approximately 20% of the sample, while those in the highest category constitute 22%. Regarding education, the data reveal that more households fall within the lowest education category than any other group. Specifically, 49% of the sampled households have only nursery and primary education, while about 31% and 30% have secondary and post-secondary education, respectively. Furthermore, Table 1 shows that a relatively small fraction of the sampled households engaged in formal employment or were covered by an insurance scheme. On average, only about 16% of households in the panel sample include elderly members.

3.2. Prevalence of CHE and Forgone Medical Care Incidences

This subsection presents the results of CHE incidences calculated from the pre-COVID-19 survey2 period, 2019, and the incidences of forgone care during the COVID-19 period, 2020.

Table 2 above shows the prevalence of CHE at the national, sectoral, and zonal levels for the 2019 period using various expenditure threshold values. The CHE prevalence depends on the threshold chosen. For instance, at the 25% threshold, the CHE prevalence is roughly 17%, whereas at the 10% threshold, it is 41%. The CHE prevalence in rural areas (45%) is significantly higher compared to urban areas (35%). This trend is also evident at the zonal level: relative to the 34% prevalence in the southern zone, the northern zone prevalence remains significantly higher at approximately 48%. However, at the 25% expenditure threshold, the CHE prevalence was found to be 19% in rural areas but roughly 13% in urban areas. While it was only 13% in southern areas, it was approximately 21% in northern areas. Using the capacity-to-pay definition (i.e., the household’s income minus subsistence needs), we also determined the incidences of catastrophic medical spending across national and regional levels in column 3 of Table 2. We observe that relative to incidences calculated using a 10% share of income, incidences computed with the WHO’s 40% non-food expenditure threshold are lower. Consistent with the rural–urban and northern–southern differences in prevalence using 10% and 25% thresholds, the prevalence using the 40% non-food expenditure threshold reveals a higher level in the rural and northern areas compared to urban and southern areas.

Table 3 above reports the prevalence of forgone care and reasons for forgoing care both as a percentage of all sampled households and as a percentage of households that needed medical care. For our interpretation, and in line with the previous literature (Rahman et al., 2022; Kakietek et al., 2022), we focus on the prevalence of forgone care as a percentage of households that needed medical care. From column 1 of Table 3, we observe that a considerable share, 13% of the households, forwent care in wave 1 when the COVID-19 restriction was in full effect. On average, this level of forgone care is roughly 4.7 percentage points lower than the sub-Saharan African average forgone care level of 17.4%, as reported by Kakietek et al. (2022). However, this rate slightly declined to 12% in wave 2, when the lockdown measure was partially lifted (see column 2 of Table 3). Furthermore, Table 3 shows that the levels of forgone care due to financial barriers (including a lack of money for medical care and a lack of transportation) were relatively higher. This result is similar to the findings reported by Kakietek et al. (2022) and Menon et al. (2022). Kakietek et al. (2022) confirmed that in poorer countries, including sub-Saharan African countries, financial constraints were the most commonly reported reasons for forgoing healthcare during the COVID-19 period. This result also aligns with the findings of Menon et al. (2022) for Switzerland.

Specifically, in column 1 of Table 3, we see that 11% of households in need of medical care were unable to access it due to financial constraints during wave 1 when the lockdown measures were fully in effect. However, this rate of forgone care decreased to 9.5% in wave 2 following the partial lifting of legal restrictions. This outcome aligns with the findings by Kakietek et al. (2022), which highlight that a substantial proportion of households in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) had to forgo healthcare in the early months of the pandemic. Furthermore, reasons related to COVID-19 lockdown measures or fear of contracting the virus while seeking care accounted for 2% of forgone care cases in the initial months of the pandemic, with this figure declining to 0.3% when movement restrictions were eased. Similarly, supply-related factors—such as health facilities being at full capacity, closures, or shortages of medical staff and supplies—contributed to 2% of forgone care cases in the early months of the pandemic and dropped to 1% when legal restrictions were relaxed.

Table 4 reveals disparities in household expenditures across regions and urban–rural divides, aligning with previous studies on household spending patterns in developing countries. Wealthier households spend considerably more across all categories, with medical expenses in the highest quintile (₦3959.3) being nearly three times that of the poorest quintile (₦1357.6) and total expenditure (₦40,256.4) being almost seven times higher than that of the lowest quintile (₦5980.4), consistent with findings by O’Donnell et al. (2008), who documented strong income gradients in healthcare spending. Urban households also exhibit higher spending, with a mean total expenditure of ₦24,512.3 compared to ₦15,953.3 in rural areas, and non-food expenditures (excluding medical costs) nearly tripling (₦8857.7 in urban vs. ₦3485.9 in rural areas). These findings mirror patterns observed by Gwatkin et al. (2007) on urban–rural health inequalities in low-income countries. These findings highlight stark income-driven inequalities in healthcare affordability and access, emphasizing the need for targeted policies, such as health subsidies and expanded insurance coverage, to improve healthcare access for lower-income and rural populations (Edeh, 2022).

Table 5 highlights that urban households allocate a smaller share to medical costs (12.4%) and food (55.8%) than rural households (18.1% and 63.9%, respectively), suggesting that healthcare costs pose a greater financial burden in rural areas (Gwatkin et al., 2007). Across income quintiles, medical spending as a share of total expenditures declines from 23.3% in the lowest quintile to 10.9% in the highest, while food expenditure shares also decrease with income, reinforcing the pattern that poorer households prioritize essential needs. Conversely, non-food expenditures (excluding medical costs) rise from 11.8% in the lowest quintile to 33.8% in the highest, indicating greater financial flexibility among wealthier households. These findings underscore the urgent need for targeted policies, such as expanded health insurance coverage and income support, to alleviate the financial burden of healthcare on lower-income and rural populations (Xu et al., 2003).

3.3. Effect of COVID-19 Legal Restrictions on CHE and Forgone Medical Care

In this subsection, we present the regression results on the effect of COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE and forgone care. Before introducing the panel logit model estimates, we first present the cross-section logit analyses for wave 1 (conducted in April 2020), when the COVID-19 legal restriction was in full effect, and wave 2 (conducted in June–July 2020), when the legal restriction was partially lifted.

The results in Table 6 present the logit effects of COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE and forgone care for wave 1, when the government’s lockdown measure was in full effect. Columns 1 and 3 of Table 6 showcase the logit coefficients of the CHE and forgone care regression models. Note that the pseudo R2 values appear to be relatively low. This is not surprising in cross-sectional regressions, as heterogeneity across cross-sectional units can lead to lower explanatory power, especially when dealing with a large number of observations (Gujarati & Porter, 2009). However, the pseudo R2 values remain statistically significant based on the Wald test. Table 6 shows that the probability values associated with the Wald test statistics are very low. Hence, we can reject that the coefficients of the regressions are zero (Gujarati & Porter, 2009). To facilitate interpretation in a non-linear setting, we prioritize the marginal effects over the raw coefficient estimates. According to the marginal effects estimates in column 2, households’ vulnerability to COVID-19 legal restrictions reduced the probability of experiencing CHE by 8%. This result is unsurprising, as the COVID-19 lockdown measure prevented many households from accessing their workplaces, leading to job losses and reduced income. A loss of income results in lower medical spending, which in turn decreases the likelihood of households incurring CHE (Abor & Abor, 2020). However, we suspect that this result also suggests that households are forgoing healthcare (Tandon et al., 2020). This aligns with the argument that households unable to afford healthcare services do not incur CHE but instead forgo healthcare (Pradhan & Prescott, 2002). The finding above is confirmed by the estimates in column 4, which show that households’ susceptibility to COVID-19 legal restrictions increases the probability of forgoing medical care by 5%.

Table 6.

Cross-section estimates—effects of COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE and forgone care in wave 1.

Furthermore, the results in column 2 reveal that female household heads are 2% more likely to experience CHE relative to male household heads. However, column 4 shows that female household heads are 3% less likely to forgo healthcare relative to male household heads. Households in rural areas are 1.3% less likely to incur CHE than those in urban areas. This is quite similar to the results in column 4, showing that households in rural areas are 3% less likely to forgo healthcare relative to their urban counterparts. However, households in northern areas are 5% more likely to incur CHE and 1% more likely to forgo healthcare than those in southern regions. As expected, households in the highest income quintile (the richest) are significantly less likely to incur CHE than those in the lowest income quintile (the poorest). Specifically, the richest households are 24% less likely to experience CHE, while those in the second poorest quintile are only 11% less likely to experience CHE compared to the poorest households. Similarly, column 4 confirms that wealthier households are less likely to forgo healthcare relative to poorer households.

Household heads educated to the post-secondary level are 7% less likely to incur CHE relative to household heads with no formal education. In line with this result, household heads educated to the post-secondary level are also 7% less likely to forgo healthcare compared to household heads with no formal education. Employed households are 25% less likely to experience CHE relative to unemployed household heads. Similarly, employed household heads are 3% less likely to forgo healthcare compared to unemployed household heads. As expected, insured households are 5% less likely to incur CHE relative to uninsured households. Consistent with the previous literature, elderly household members (aged 60 years and above) are 2% more likely to experience CHE relative to non-elderly members. However, this contrasts with the findings on forgone care in column 4, which shows that non-elderly members are more likely to forgo healthcare relative to elderly members of the household.

The results in Table 7 present the effect of COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE and forgone care during wave 2 when the lockdown measures were partially lifted. In terms of CHE, the coefficient on COVID-19 is statistically insignificant, indicating that the restrictions had no effect on CHE. However, compared to the results from wave 1, we observe a reversal in the sign of the coefficients. Unlike in wave 1, the sign of COVID-19 legal restrictions is now positive. During this period of partial lockdown, some households were able to return to work and earn income. Unlike the full lockdown period, which was associated with limited income, households now had some financial relief, allowing them to spend more on medical care. This increase in OOP spending on medical expenditures raised the likelihood of incurring CHE. However, this shift did not reverse the effect of COVID-19 legal restrictions on forgone care. Similar to the findings from the full lockdown period, COVID-19 legal restrictions continued to increase forgone care in wave 2. Specifically, exposure to COVID-19 legal restrictions increased the likelihood of households forgoing medical care by 7%. Similar to the trend we found in wave 1, female household heads are 1% more likely to experience CHE relative to their male counterparts in wave 2 (see column 2 of Table 7). This contradicts the results in column 4 of Table 7, showing that female household heads are 2% less likely to forgo healthcare relative to male household heads. The results of the sector of the households remain similar across waves 1 and 2. While the effects of zonal location on CHE were consistent across waves 1 and 2, the effect on forgone care was reversed. Specifically, in wave 1, households residing in the northern region were 1% more likely to incur forgone care relative to households in the southern region. However, in wave 2, households in the northern region were 5% less likely to incur forgone care compared to households in the southern region.

Table 7.

Cross-section estimates—effects of COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE and forgone care in wave 2.

Similar to the results from wave 1, households in the highest income quintile (the richest) are more likely to experience a reduction in CHE relative to households belonging to the lowest income quintile (the poorest) in wave 2. Also, households in the highest income quintile (the richest) are more likely to experience a reduction in forgone healthcare relative to households belonging to the lowest income quintile (the poorest) (see columns 2 and 4 of Table 7). As shown in columns 2 and 4 of Table 7, household heads educated up to the secondary level are 2% and 6% less likely to experience CHE and forgone care, respectively, relative to household heads without secondary education. The results of employment status are similar across waves 1 and 2. As in wave 1, employed households are less likely to experience CHE and forgo care relative to unemployed household heads in wave 2. Similar to the findings from wave 1, having health insurance reduces the probability of incurring CHE relative to not having health insurance in wave 2. Analogous to wave 1, the elderly members of households are more likely to incur CHE relative to non-elderly members. However, non-elderly members are more likely to forgo healthcare compared to elderly members of households in wave 2 (columns 2 and 4 of Table 7).

Table 8 presents the panel regression outcomes of the effect of COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE and forgone medical care. Our panel analyses reveal that households’ exposure to COVID-19 legal restrictions reduces the probability of incurring CHE but increases the probability of forgoing care due to financial reasons, as seen in column 2, and due to any reason (which could be financial—a lack of money and transportation, COVID-19, or supply reasons—a lack of medical personnel/medical supplies), as seen in column 3. Specifically, households’ vulnerability to COVID-19 legal restrictions reduces the likelihood of incurring CHE by 2%. However, it increases the probability of households forgoing care by 3% for financial reasons and 2% for any reason. These findings are in alignment with those of previous related studies, showing that the COVID-19 pandemic led to a national-level decline in CHE incidence (Pan et al., 2021) in Indonesia and increased forgone medical care (decreased utilization of medical services) (Pan et al., 2021; Menon et al., 2022) in Indonesia and Geneva. We now conclude that the COVID-19 lockdown measures prevented many households from accessing their workplaces—leading to some loss in income and medical spending (Abor & Abor, 2020). This, in turn, implies a possible reduction in the probability of households incurring CHE. But, as we see in columns 2 and 3, this result leads to households forgoing healthcare. Households that are not able to afford healthcare services do not incur CHE but forgo healthcare (Pradhan & Prescott, 2002). This is in line with the argument that declining medical spending due to COVID-19 will likely cause OOP shares of income/consumption to improve (a reduction in catastrophic medical spending). However, these “improvements” are delusory, as they are caused by forgone medical care rather than improvements in healthcare coverage (Tandon et al., 2020).

Table 8.

Panel (random effects) estimates—effects of COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE and forgone care.

In terms of gender, our panel results in column 1 (Table 8) align with those from the cross-sectional analyses for waves 1 and 2. We observe from the panel results that female household heads are more likely to experience CHE relative to male household heads. This result, showing that female-headed households are more likely to incur CHE relative to their male counterparts, is consistent with the existing literature (e.g., Lee & Yoon, 2019; Mutyambizi et al., 2019), which suggests that women are relatively more vulnerable groups and that their spending on needed healthcare may lead to a financial catastrophe. Therefore, if female-headed households spend on healthcare, even when such spending could be catastrophic, they are less likely to forgo care relative to male-headed households (columns 2 and 3 of Table 8). We further conclude that households residing in rural areas and northern zones are more likely to incur CHE compared to households residing in urban areas and southern zones in the country (column 1 of Table 8). Households residing in rural areas and northern zones are 3% and 5% more likely to incur CHE relative to households residing in urban areas and southern zones, respectively. In terms of forgone care for both financial or any reason, households residing in rural areas and northern zones are more likely to forgo care than those in urban areas and southern zones. These regional findings are confirmed by previous studies (Barasa et al., 2017; Shumet et al., 2021; Kwesiga et al., 2020). The vulnerable groups, such as the poor, are more often located in rural areas and northern regions where incomes and welfare are relatively lower. This explains why residing in these parts of the country is associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing CHE and forgoing care.

Our panel regression results confirm that households in the highest income quintile (the richest) are more likely to experience a reduction in CHE and forgone care due to financial reasons and for any reason relative to households belonging to the lowest income quintile (the poorest). In particular, households belonging to the richest income group are 44% less likely to incur CHE relative to households belonging to the poorest income group. However, households belonging to the second-poorest income group are only 13% less likely to experience CHE relative to households belonging to the poorest income group (column 1 of Table 8). Moreover, belonging to the richest income group reduces the probability of forgoing care due to financial reasons and for any reason by 5% and 4%, respectively, unlike belonging to the second-poorest income group, which increases the probability of forgoing care by 4% (columns 2 and 3 of Table 8). This has been confirmed by numerous related studies acknowledging that poor households have a higher likelihood of incurring CHE (e.g., Adisa, 2015; Aregbeshola & Khan, 2018) and forgoing medical care (Bremer, 2014; Rahman et al., 2022; Menon et al., 2022). Hence, to ensure equal access to healthcare, the government needs to improve health insurance coverage. The coverage of health insurance is still quite low, at only about 3% in Nigeria. This implies that the population that remains unprotected from the financial hardship of huge medical bills is about 97%, mainly comprising the poor and vulnerable groups (Nigeria Ministry of Health, 2021).

Households educated at least to the secondary level are 2%, 2%, and 3% less likely to incur CHE and forgo care due to financial reasons and for any reason, respectively, relative to households with no education. Being educated or employed increases the chances of higher earnings, and increased earnings enable the household to afford needed medical services without experiencing financial catastrophe. Hence, we found that household heads who are educated or employed reduce the likelihood of experiencing CHE and forgoing medical care. These results are confirmed by outcomes from previous related studies (e.g., Li et al., 2018; Edeh, 2022). This implies that improving education access and attainment through government scholarships and funding is necessary to enhance individuals’ earning capacity, thus reducing the likelihood of experiencing CHE and forgoing medical care. Moreover, promoting employment opportunities through the government’s encouragement of the private sector will increase individuals’ earning capacities. This, in turn, will enable individuals to afford healthcare, thereby reducing the chances of incurring CHE and forgoing healthcare.

Our panel results confirm that having employment and health insurance reduces the probability of households incurring CHE and forgoing care for both financial and any other reason. Specifically, employed and insured households are 10% and 12% less likely to incur CHE relative to households with no employment and insurance, respectively. Similarly, employed and insured households are 2% and 2% less likely to forgo care due to financial constraints, respectively, and 4% and 5% less likely due to any other reason, respectively, relative to those who are unemployed and uninsured. When all households are covered by the national health insurance scheme, medical services become reasonably subsidized. This implies that all vulnerable groups would be able to access necessary quality medical services without experiencing any form of financial hardship. Hence, there is a need to expand health insurance to cover the poor and vulnerable groups in the country. Additionally, the government should encourage enrollment into the scheme for everyone in both the formal and informal sectors. This can be achieved through public awareness campaigns for the people and engagement of key stakeholders and users in the design and implementation of health communication strategies for health insurance.

Elderly members of households are more likely to incur CHE relative to non-elderly members. Moreover, elderly members of households are more likely to forgo healthcare due to both financial reasons and other reasons compared to non-elderly members of households. Elderly members of households are a vulnerable group usually residing in poor regions (i.e., the rural areas). They are often unable to afford necessary medical services due to a limited income. Hence, in our study, we found that being elderly is associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing CHE and forgoing medical care. Previous related studies (e.g., Rahman et al., 2022) also confirm these findings. To assist the elderly in accessing necessary medical services without suffering financial hardship during and beyond the pandemic crisis, the government should ensure that elderly individuals are well-covered by the national health insurance scheme.

4. Summary of Findings and Policy Implications

Leveraging a comprehensive set of up-to-date pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 micro-panel household survey datasets from Nigeria, this study attempts to address two specific questions. First, how catastrophic is the effect of COVID-19 on OOP medical spending? Second, to what extent is the effect of COVID-19 on needed medical care forgone due to a lack of income? In response to these questions, the study presents several crucial findings.

In the early months of COVID-19, when the government lockdown measure was in full effect, COVID-19 legal restrictions were found to have a significant negative effect on CHE. However, the legal restrictions were found to have a significant positive effect on forgone medical care, both due to financial reasons and any other reason. The negative effect of the legal restrictions on CHE can be attributed to the loss in income and decreased demand for health services experienced by poor households during the COVID-19 period, which led to a decline in medical spending and a possible reduction in the probability of the households incurring CHE (Abor & Abor, 2020). However, if households do not incur CHE because they are not able to afford medical care, it implies they are forgoing care (Pradhan & Prescott, 2002). This supports our finding of the significant positive effect of the legal restrictions on forgone care. Simply put, many households were forgoing care during the COVID-19 lockdown period. In wave two, when the lockdown measures were partially lifted, we observed a positive effect of the COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE. Similarly, as in wave one, the significant positive effect of COVID-19 legal restrictions on forgone care was also observed in wave two. We attribute the positive effect of COVID-19 legal restrictions on CHE in wave two to the partial lifting of the lockdown measures, which allowed households to access their workplaces, earn income, and spend more on medical care. Increased spending on healthcare could become catastrophic if it exceeds a given income threshold. Moreover, our results showing the significant positive effect of COVID-19 on forgone care suggest that, even with the partial lifting of the lockdown measures, many households were still unable to access medical care.

Our panel regression analyses confirm that the COVID-19 legal restrictions significantly reduce CHE but significantly increase forgone care. Furthermore, based on the results of our panel regression, female household heads are faced with a significantly higher likelihood of incurring CHE relative to male household heads. However, in terms of forgone care, male household heads face a significantly higher probability of forgoing care compared to female household heads. Residing in rural areas and northern zones is associated with an increased likelihood of incurring CHE relative to residing in urban areas and southern zones. Similarly, residing in rural areas and northern zones is associated with an increased likelihood of forgoing care relative to residing in urban areas and southern zones in the country.

Our panel regression results confirm that households in the highest income quintile (the richest households) are more likely to experience a reduction in CHE and forgone care relative to households in the lowest income quintile (the poorest). Having some level of education is associated with a lower likelihood of incurring CHE and forgoing care relative to having no education. Additionally, having employment and health insurance significantly reduces the probability of households incurring CHE and forgoing care relative to households without employment and insurance. Elderly members of households are more likely to incur CHE and forgo healthcare relative to non-elderly members.

The economic implications of this study are profound, highlighting the critical intersection between healthcare financing and Nigeria’s broader economic stability. The key findings show that COVID-19-induced restrictions led to increased forgone medical care, particularly among financially vulnerable households. This has serious macroeconomic consequences, as poor health reduces labor productivity, workforce participation, and overall economic output. Studies have shown that improvements in life expectancy and access to healthcare significantly enhance labor productivity in Nigeria (Ugwu et al., 2020). However, with out-of-pocket (OOP) payments making up about 70% of total health expenditures in Nigeria (Edeh, 2022), many households face severe financial strain, often pushing them into poverty. Research indicates that OOP health payments have led to a 0.8% increase in Nigeria’s poverty headcount, affecting approximately 1.3 million people (Aregbeshola & Khan, 2018). Hence, strengthening healthcare financing is not just a social imperative but an economic necessity to break the cycle of poor health, reduced earnings, and poverty. Addressing these challenges will enhance Nigeria’s economic resilience and ensure sustainable development, particularly in the face of future health crises (Ololo, 2022).

The study notes that the Nigerian government implemented several assistance programs during the pandemic, including direct cash transfers, food aid, and health system interventions. Programs such as the Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) and the COVID-19 Rapid Response Register (RRR) for poor households provided financial relief to vulnerable groups (World Bank, 2021a). The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) also introduced targeted credit facilities for households and small businesses affected by the pandemic (CBN, 2020). In the healthcare sector, the government increased funding for medical supplies and emergency health responses through the COVID-19 Crisis Intervention Fund (Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning, 2021).

While these measures helped mitigate the broader economic impact of the pandemic, their direct effect on reducing OOP medical spending was limited (Aregbeshola & Folayan, 2022). The CCT and RRR programs provided households with extra income, which may have indirectly supported healthcare expenses. However, the absence of widespread financial protection mechanisms, such as universal health insurance coverage, meant that many low-income households still faced high OOP costs when seeking medical care (Aregbeshola & Folayan, 2022; Okeke et al., 2022). The Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN, 2020) credit facilities, aimed at cushioning financial shocks, helped some households maintain healthcare expenditures, but these were largely indirect effects rather than systematic reductions in OOP medical costs. As research has shown, households, especially those in lower-income brackets, continued to forgo needed care due to financial constraints, underscoring the need for stronger, more direct financial protections, such as health insurance expansion and targeted subsidies (Aregbeshola & Folayan, 2022).

Although this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, its relevance extends beyond that period, as economic shocks continue to shape healthcare spending and access (Grafova et al., 2020). The findings contribute to the broader understanding of how crises—such as pandemics and inflationary shocks—affect out-of-pocket (OOP) medical expenditures and forgone care, particularly among vulnerable populations (Rufai et al., 2021). For example, Nigeria is currently experiencing inflationary pressures that have eroded household purchasing power, leading to constrained healthcare spending and increased health-related financial risks (Uzor et al., 2024). Similar to the COVID-19 crisis, economic downturns and price volatility can drive households to reduce essential medical expenditures, reinforcing the need for policies that strengthen financial protection mechanisms, such as expanded health insurance coverage and social safety nets (Ipinnimo et al., 2023). Thus, the study’s insights remain highly relevant in guiding responses to both past and ongoing economic challenges affecting healthcare affordability.

This study has certain limitations. First, due to data constraints, it does not examine forgone care for specific types of healthcare services, such as child immunization or maternal health services (antenatal or postnatal care). While households provided information on forgone medical care, the specific healthcare service remains unclear. Second, the out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure data used in this study were collected for general medical purposes. For example, while households provided information on payments for medicine, the specific illnesses these payments were associated with remain unclear. Analyzing OOP expenses at a general level obscures details about medical costs for particular conditions, such as HIV/AIDS or cardiovascular diseases. Given these limitations, this study highlights potential areas for future research. First, future studies could focus on collecting data on specific healthcare services to allow for a more detailed analysis of COVID-19’s impact on forgone medical care. Second, further research could explore the catastrophic financial burden of OOP payments for specific illnesses (e.g., malaria, typhoid fever, HIV/AIDS, or cardiovascular diseases) within particular states or local government areas in Nigeria.

As previously mentioned, the key finding is that the COVID-19 legal restrictions reduced CHE through a decline in household medical spending. This decrease in household medical spending due to COVID-19 restrictions has led to forgone medical care (i.e., reduced access to quality healthcare services). This result suggests that a better policy design is needed to address the impact of COVID-19 on health spending and safeguard household welfare against future pandemics. Therefore, public health policy efforts, particularly those aimed at increasing the depth and coverage of health insurance, will broaden access to quality healthcare services both during and beyond pandemic periods.

Author Contributions

H.C.E. conceived the idea and developed the theoretical framework. H.C.E. and J.O.O. conducted the data analyses and interpreted the results. All three authors contributed to and discussed the literature review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted with funding from African Economic Research Consortium (AERC), under the AERC collaborative project on “Addressing Healthcare Financing Vulnerabilities in Africa due to the COVID-19 Pandemic”, Grant No RC22518.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used are publicly available from the Living Standards Measurement (LSMS) website: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/lsms/?page=1&ps=15&repo=lsms (accessed on 28 January 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Note that the 51% represents the average across the samples in both wave 1 and wave 2 of the panel sample. In wave 1, when the lockdown measure was fully in effect, the estimate of households affected was higher at 59%, compared to 41% in wave 2, when the lockdown measure was partially lifted. |

| 2 | The CHE variable was calculated from the pre-COVID-19 survey. However, variables necessary for calculating CHE (out-of-pocket payments and income/consumption expenditure) were not included in the COVID-19 survey. Hence, we were unable to calculate the CHE variable for the COVID-19 period. Nevertheless, the households in the pre-COVID-19 survey are the same households studied in the COVID-19 period, which allows us to merge and append the datasets to form a panel. To enable a cross-sectional examination of the effect of COVID-19 legal restriction on CHE, we merged the pre-COVID-19 and the COVID-19 variables. For the panel analyses these datasets were appended across the first two waves of the COVID-19 survey periods. |

References

- Abor, A. P., & Abor, J. Y. (2020). Implications of COVID-19 pandemic for health financing system in Ghana. Journal of Health Management, 22(4), 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, O. (2015). Investigating determinants of catastrophic health spending among poorly insured elderly households in urban Nigeria. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S., Ahmed, M. W., Hasan, M. Z., Mehdi, G. G., Islam, Z., Rehnberg, C., Louis W. Niessen, L. W., & Khan, J. A. M. (2022). Assessing the incidence of catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment from out-of-pocket payments and their determinants in Bangladesh: Evidence from the nationwide Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2016. International Health, 14, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aregbeshola, B. S., & Folayan, M. O. (2022). Nigeria’s financing of health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and recommendations. World Medical and Health Policy, 14, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aregbeshola, B. S., & Khan, S. M. (2018). Out-of-pocket payments, catastrophic health expenditure and poverty among households in Nigeria 2010. International Journal of Health Policy Management, 7(9), 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataguba, J. E., Ichoku, H. E., Ingabire, M.-G., & Akazili, J. (2022). Financial protection in health revisited: Is catastrophic health spending underestimated for service- or disease specific analysis? Health Economics, 33(6), 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasa, E. W., Maina, T., & Ravishankar, N. (2017). Assessing the impoverishing effects, and factors associated with the incidence of catastrophic health care payments in Kenya. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIN, J. B., Ofeh, M. A., & CHE, S. B. (2020). Impact of the corona pandemic on household welfare in Cameroon. Journal of Economics and Management Sciences, 3(3), 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, P. (2014). Forgone care and financial burden due to out-of-pocket payments within the German health care system. Health Economics Review, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, J., Sood, N., Bravata, D. M., Pera, M., & Whaley, C. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy response on health care utilization: Evidence from county-level medical claims and cell phone data. Journal of Health Economics, 82, 102581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Nigeria. (2020). Guidelines for the implementation of the N50 billion targeted credit facility. Available online: https://www.cbn.gov.ng/out/2020/fprd/n50%20billion%20combined.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- COVID-19 NLPS Report. (2020). Nigeria COVID-19 National Longitudinal Phone Survey (NLPS). Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3712 (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Edeh, H. C. (2022). Exploring dynamics in catastrophic health care expenditure in Nigeria. Health Economics Review, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, P., Lawani, L. O., Aguc, U. J., & Acharyaa, Y. (2022). Catastrophic health expenditure in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 100(5), 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabani, J., & Guinness, L. (2019). Households forgoing healthcare as a measure of financial risk protection: An application to Liberia. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S., Bebarta, K. K., Tripathi, N., & Krishnendhu, C. (2022). Catastrophic health expenditure due to hospitalisation for COVID-19 treatment in India: Findings from a primary survey. BMC Research Notes, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getachew, N., Shigut, H., Edessa, G. J., & Yesuf, E. A. (2023). Catastrophic health expenditure and associated factors among households of non-community based health insurance districts, Ilubabor zone, Oromia regional state, southwest Ethiopia. International Journal for Equity in Health, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grafova, I. B., Monheit, A. C., & Kumar, R. (2020). How do economic shocks affect family health care spending burdens? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 41, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W. H. (2010). Econometric analysis (7th ed.). New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H., Kou, Y., Yan, Z., Ding, Y., Shieh, J., Sun, J., Cui, N., Wang, Q., & You, H. (2017). Income related inequality and influencing factors: A study for the incidence of catastrophic health expenditure in rural China. BMC Public Health, 17, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, C. D. (2009). Basic econometrics (5th ed.). McGRAW. [Google Scholar]

- Gwatkin, D. R., Rustein, S., Johnson, K., Pande, R., & Wagstaff, A. (2007). Socio-economic differences in health, nutrition, and population in developing countries. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Haakenstad, A., Bintz, C., Knight, M., Bienhoff, K., Chacon-Torrico, H., Curioso, W. H., Dieleman, J. L., Gage, A., Gakidou, E., Hay, S. I., Henry, N. J., Hernández-Vásquez, A., Méndez Méndez, J. S., Villarreal, H. J., & Lozano, R. (2023). Catastrophic health expenditure during the COVID-19 pandemic in five countries: A time-series analysis. Lancet Global Health, 11, e1629–e1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichoku, H. E. (2005). A distributional analysis of healthcare financing in a developing country: A nigerian case study applying a decomposable Gini index [Ph.D. thesis, University of Cape Town]. [Google Scholar]

- Igbokwe, U., Ibrahim, R., Aina, M., Umar, M., Salihu, M., Omoregie, E., Sadiq, F. U., Obonyo, B., Muhammad, R., Isah, S. I., Joseph, N., Wakil, B., Tijjani, F., Ibrahim, A., & Yahaya, M. N., Jr. (2024). Evaluating the implementation of the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) gateway for the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund (BHCPF) across six Northern states in Nigeria. BMC Health Services Research, 24, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Trade Centre. (2020). SME competitiveness outlook 2020: COVID-19: The great lockdown and its impact on small business. ITC. [Google Scholar]

- Ipinnimo, T. M., Adeniyi, I. O., Osuntuyi, O. M.-M., Ehizibue, P. E., Ipinnimo, M. T., & Omotoso, A. A. (2023). The unspotted impact of global inflation and economic crisis on the Nigerian healthcare system. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 18(1), i2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H., Yang, J., Kim, E., & Lee, J. (2021). The Effect of mid-to-long-term hospitalization on the catastrophic health expenditure: Focusing on the mediating effect of earned income loss. Healthcare, 9, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakietek, J. J., Eberwein, J. D., Stacey, N., Newhouse, D., & Yoshida, N. (2022). Foregone healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic: Early survey estimates from 39 low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy and Planning, 37(6), 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kien, V. D., Minh, H. V., Giang, K. B., Dao, A., Tuan, L. T., & Ng, N. (2016). Socioeconomic inequalities in catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment associated with non-communicable diseases in urban Hanoi, Vietnam. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwesiga, B., Aliti, T., Nabukhonzo, P., Najuko, S., Byawaka, P., Hsu, J., Ataguba, J. E., & Kabaniha, G. (2020). What has been the progress in addressing financial risk in Uganda? Analysis of catastrophe and impoverishment due to health payments. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S. J., Ritchey, M. D., Goodman, A. B., Dias, T., Twentyman, E., Fuld, J., & Gundlapalli, A. V. (2020). Potential indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on use of emergency departments for acute life-threatening conditions—United States, January–May 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(25), 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M., & Yoon, K. (2019). Catastrophic health expenditures and its inequality in households with cancer patients: A panel study. Processes, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leive, A. (2008). Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: Empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Chen, M., & Wang, Z. (2018). Forgone care among middle aged and elderly with chronic diseases in China: Evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study baseline survey. BMJ Open, 8, e019901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascagni, G., & Santoro, F. (2021). The tax side of the pandemic: Compliance shifts and funding for recovery in Rwanda (ICTD Working Paper 129). International Centre for Tax and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Matebie, G. M., Mebratie, A. D., Demeke, T., Afework, B., Kantelhardt, E. J., & Adamu Addissie, A. (2024). Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Associated Factors among Hospitalized Cancer Patients in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 17, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, D. (2007). Learning from experience: Health care financing in low- and middle-income countries (Helping Correct the 10|90 Gap). Global Forum for Health Research. Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/48554/2007-06%20Health%20care%20financing.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Menon, L. K., Richard, V., Mestral, C., Baysson, H., Wisniak, A., Guessous, I., Stringhini, S., & the Specchio-COVID19 Study Group. (2022). Forgoing healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic in Geneva, Switzerland—A cross-sectional population-based study. Preventive Medicine, 156, 106987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielck, A., Kiess, R., Knesebeck, O., Stirbu, I., & Kunst, A. E. (2009). Association between forgone care and household income among the elderly in five Western European countries—Analyses based on survey data from the SHARE-study. BMC Health Services Research, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning. (2021). Ministerial press statement on fiscal stimulus measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and oil price fiscal shock. Available online: https://pwcnigeria.typepad.com/tax_matters_nigeria/2020/04/covid-19-federal-government-of-nigeria-announces-fiscal-stimulus-measures.html (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Mutyambizi, C., Pavlova, M., Hongoro, C., Booysen, F., & Groot, W. (2019). Incidence, socio economic inequalities and determinants of catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment for diabetes care in South Africa: A study at two public hospitals in Tshwane. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NBS. (2019). Basic information document, nigeria general household survey—Panel, 2018/2019. Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3557/related-materials (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- NBS. (2021). Basic information document Nigeria COVID-19 national longitudinal phone survey (COVID-19 NLPS) version 12 (updated on August 2021). Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3712/related-materials (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Nigeria Ministry of Health. (2021). National Health Account (NHA) 2017: Final Technical report of the federal ministry of health. Available online: https://p4h.world/en/documents/nigeria-national-health-accounts-nha-2017/ (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Obi-Ani, N. A., Ezeaku, D. O., Ikem, O., Isiani, M. C., Obi-Ani, P., & Chisolum, O. J. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and the Nigerian primary healthcare system: The leadership question. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 8, 1859075. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, O., van Doorslaer, E., Wagstaff, A., & Lindelow, M. (2008). Analyzing health equity using household survey data: A guide to techniques and their implementation. World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2020). COVID-19 in Africa: Regional socio-economic implications and policy priorities. Tackling coronavirus (COVID-19) contribution to a global effort. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/covid-19-and-africa-socio-economic-implications-and-policy-responses_96e1b282-en.html (accessed on 12 August 2023).

- Ogundare, E. O., Taiwo, A. T., Olatunya, O. S., & Afolabi, M. O. (2022). Incidence of Catastrophic Health Expenditures amongst Hospitalized Neonates in Ekiti, Southwest Nigeria. ChincoEconomics and Outcome Research, 14, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]