1. Introduction

Since 1994, Mexico’s central bank, Banco de México (Banxico), has implemented an inflation-targeting (IT) framework as its primary monetary policy strategy, following the abandonment of the exchange rate as a nominal anchor. This transition aligns with a global trend initiated by economies such as New Zealand and Canada, which have demonstrated improved macroeconomic performance under this regime (

Mishkin & Schmidt-Hebbel, 2007;

Svensson, 2001). The IT framework aims to stabilize inflation expectations by publicly announcing a medium-term target, thereby enhancing credibility and mitigating inflation persistence in response to economic shocks. This approach is grounded in the New Macroeconomic Consensus (NMC), which underscores the importance of central bank accountability, transparency, and independence in monetary policy implementation (

Woodford, 2009).

While some analyses suggest a positive correlation between inflation and GDP growth in Mexico, this observed relationship does not fully capture the role of inflation uncertainty in shaping investment and output dynamics. This study therefore focuses not on inflation levels per se but on the volatility and predictability of inflation, which may exert nonlinear and asymmetric effects on economic performance, particularly in emerging markets.

Although Mexico has achieved relative price stability since the early 2000s, recent global disruptions, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia–Ukraine conflict, and escalating trade tensions among major economic partners such as the United States and China, have renewed inflationary pressures, even in economies with long-standing inflation targeting frameworks. These events have exposed the limitations of monetary policy autonomy in highly integrated markets, where imported inflation and supply chain shocks amplify domestic price volatility. In this context, it becomes essential to revisit the inflation–growth nexus through the lens of inflation uncertainty. Converging inflation rates across countries do not necessarily imply symmetric macroeconomic effects, especially for emerging economies like Mexico that remain structurally vulnerable to external shocks and institutional fragility. Thus, reassessing the resilience and credibility of Mexico’s inflation-targeting regime is particularly relevant considering these evolving global dynamics.

The relationship between inflation and economic growth has long been a subject of debate. Early theoretical and empirical studies (

Fisher, 1926;

Phillips, 1958;

Tobin, 1965) suggested a positive correlation, arguing that moderate inflation could stimulate production. However, the high-inflation episodes of the 1970s and 1980s shifted the consensus toward recognizing its detrimental effects, with research highlighting its adverse impact on purchasing power and economic expansion (

Friedman, 1977;

Stockman, 1981). More recent studies suggest a nonlinear relationship, proposing that inflation may exert neutral or slightly positive effects up to a specific threshold, beyond which it becomes harmful (

Bruno & Easterly, 1998;

Easterly & Rebelo, 1993).

This study focuses on the role of inflation uncertainty in shaping economic performance within the context of a globalized and shock-prone environment. Rather than testing a single theoretical hypothesis, the analysis emphasizes the evolving relevance of inflation uncertainty as a policy concern, particularly in emerging economies subject to external volatility. While inflation targeting has helped to stabilize expectations, persistent inflation volatility and credibility challenges may still influence output and investment dynamics. Therefore, this research examines whether Mexico’s inflation-targeting framework has effectively reduced inflation uncertainty and, consequently, its impact on economic performance over the period 1995–2019.

Specifically, the study addresses the following research questions:

How does the relationship between inflation and inflation uncertainty manifest in the Mexican economy?

What are the specific effects of inflation uncertainty on Mexico’s economic performance, particularly in terms of output volatility?

To what extent has Mexico’s inflation-targeting framework been effective in reducing inflation uncertainty, and what lessons can be drawn for other emerging economies?

This research contributes to the ongoing academic discourse by providing empirical evidence from a country that has undergone significant inflationary transformations. The findings hold substantial policy implications, particularly in evaluating the effectiveness of inflation targeting in reducing macroeconomic volatility and fostering stable growth.

2. Literature Review

Inflation targeting has been widely advocated as a monetary policy framework aimed at stabilizing inflation levels, anchoring expectations, and mitigating uncertainty. It constitutes a fundamental pillar of the New Macroeconomic Consensus (NMC), which replaced fixed exchange rate regimes with floating rates, removed interest rate controls, and significantly deregulated financial markets (

Rosas Rojas, 2019;

Woodford, 2009). Since its widespread adoption in the 1990s, this framework has been embraced by numerous economies seeking to enhance the effectiveness of monetary policy, particularly in response to the limitations of previous exchange rate and monetary targeting strategies. The theoretical foundation of inflation targeting is deeply intertwined with the dynamic interaction between inflation, inflation uncertainty, and macroeconomic performance. This relationship has been extensively analyzed, yielding contrasting perspectives on the trade-off between inflation and economic growth. Early theoretical contributions suggested a positive correlation, wherein moderate inflation was deemed conducive to economic expansion through aggregate demand stimulation (

Fisher, 1926;

Ghosh & Phillips, 1998;

Mundell, 1963;

Tobin, 1965). However, empirical evidence from the high-inflation episodes of the 1970s and 1980s led to a paradigm shift, highlighting inflation’s adverse effects, particularly its detrimental impact on purchasing power, investment efficiency, and economic volatility (

Cooley & Hansen, 1989;

Friedman, 1977;

Stockman, 1981).

2.1. Inflation, Uncertainty, and Economic Performance

A central concern in monetary economics is the role of inflation uncertainty in shaping macroeconomic dynamics.

Friedman (

1977) posited that higher inflation exacerbates uncertainty, distorting price signals, hampering efficient resource allocation, and ultimately constraining economic growth. This hypothesis has been empirically validated as inflation volatility is frequently employed as a proxy for macroeconomic uncertainty, demonstrating its negative impact on investment decisions and productivity levels (

Fischer, 1993;

Judson & Orphanides, 1996). The academic discourse on inflation’s macroeconomic implications has evolved from a linear to a nonlinear perspective, acknowledging that inflation may exhibit threshold effects on economic growth.

Sarel (

1996) identified a structural breakpoint in the inflation–growth nexus, estimating that inflation rates below 8% exert minimal or even slightly positive effects, whereas inflation surpassing this threshold substantially impairs economic expansion. Subsequent empirical analyses have corroborated these findings, delineating varying inflation thresholds across different economic contexts (

Burdekin et al., 2004;

Ghosh & Phillips, 1998). The relationship between inflation uncertainty and economic performance remains a subject of debate. Some scholars argue that heightened uncertainty deters long-term investment, increases precautionary savings, and dampens economic growth (

Pindyck, 1991). Conversely, alternative viewpoints suggest that, under certain conditions, inflation uncertainty may encourage savings and capital accumulation, thereby offsetting some negative repercussions (

Dotsey & Sarte, 2000). Nonetheless, the prevailing consensus aligns with the notion that inflation volatility undermines economic efficiency, exacerbates risks associated with long-term economic planning, and distorts investment incentives (

Ball, 1990;

Holland, 1993).

Since the early 2000s, GARCH models have been widely used to examine the dynamic relationship between inflation uncertainty and macroeconomic performance, particularly in both emerging and advanced economies.

K. B. Grier and Perry (

2000) and

K. B. Grier et al. (

2004), applying VARMA-BGARCH and BEKK specifications to US data, found that inflation uncertainty exerts a stronger influence on inflation than output uncertainty does on growth, and that overall uncertainty tends to be negatively associated with macroeconomic performance. For Brazil,

Vale (

2005) reported a negative relationship between inflation uncertainty and output growth. In the case of Mexico,

R. Grier and Grier (

2006) and

Perrotini Hernández and Rodríguez Benavides (

2012) presented consistent findings: inflation uncertainty dampens economic growth, even when average inflation may exhibit a short-term positive effect on output. Collectively, these studies highlight the empirical validity and versatility of GARCH models in capturing volatility spillovers and assessing the broader macroeconomic implications of inflation uncertainty. Recent empirical contributions advance this debate by identifying nonlinear and threshold dynamics.

Mohammad Sadeghi et al. (

2023) found that, in the Middle East, inflation exerts no significant effect on growth below a 10.1% threshold but becomes harmful beyond it.

Chowdhury (

2024) used bivariate nonlinear GARCH-in-mean models to show that nominal uncertainty suppresses output during downturns, while real uncertainty yields regime-dependent effects. These findings support the need for adaptive monetary frameworks tailored to specific macroeconomic environments.

Eregha and Ndoricimpa (

2022), examining Nigeria, validated the Friedman and Cukierman–Meltzer hypotheses, showing that inflation uncertainty amplifies inflation and depresses growth, especially when compounded by external shocks like oil price volatility.

2.2. The Role of Central Banks in Managing Inflation Uncertainty

The capacity of central banks to mitigate inflation uncertainty is paramount to the effectiveness of inflation-targeting regimes. Empirical research underscores the critical role of central bank transparency and credibility in anchoring inflation expectations and curbing macroeconomic volatility (

Cukierman & Meltzer, 1986;

Orphanides & Williams, 2004). Nevertheless, inflation-targeting frameworks are not immune to uncertainty. External shocks, policy misalignments, and informational asymmetries between policymakers and economic agents perpetuate uncertainty regarding future inflation trajectories (

Devereux, 1989). Despite these challenges, inflation targeting has been associated with enhanced monetary stability in economies that have successfully institutionalized it (

Ball & Sheridan, 2003;

Mishkin & Schmidt-Hebbel, 2007). However, concerns persist regarding its long-term efficacy in mitigating inflation uncertainty, particularly in the context of global economic fluctuations and evolving macro-financial conditions.

Growing evidence in the monetary policy literature underscores that the effectiveness of inflation-targeting regimes in mitigating inflation uncertainty hinges critically on the credibility of central banks.

Bicchal (

2022) provided compelling cross-national evidence showing that time-varying credibility indicators, both backward- and forward-looking, are strongly associated with reductions in macroeconomic volatility. In particular, forward-looking credibility contributes to anchoring expectations and stabilizing both interest rate and inflation dynamics. Complementing this,

Dubey and Mishra (

2023) identified an “anticipation effect”, whereby central banks strategically engineer disinflation before formally adopting inflation targeting, thereby securing early credibility and locking in inflationary expectations. These findings reveal that it is not merely the adoption of an IT framework but the strategic communication and expectation management by central banks that drive credibility gains.

Arsić et al. (

2022) further highlighted that, even under institutional fragility and high dollarization, emerging-market central banks can build credibility over time through persistent application of inflation-focused regimes, ultimately fostering macroeconomic stability.

Emerging empirical evidence also challenges the assumption of uniform outcomes under inflation-targeting frameworks.

Hartmann et al. (

2022), using an Unobserved Components Stochastic Volatility (UCSV) model, showed that short-term inflation uncertainty increases when inflation diverges from target levels, even in countries that formally adopt inflation targeting, emphasizing the importance of policy consistency and credibility. In the case of South Africa,

Mandeya and Ho (

2021) found that, following the adoption of inflation targeting, inflation uncertainty ceased to significantly affect growth, pointing to potential stabilizing effects when the regime is effectively institutionalized.

Nene et al. (

2022), through a comparative regional approach, reported that some European IT countries display superior outcomes in terms of uncertainty reduction and growth support relative to their African counterparts, largely due to differences in institutional capacity and central bank credibility. Similarly,

Aromí et al. (

2022) underscored the persistent macroeconomic volatility in Latin America as a major impediment to investment and economic development, underscoring the structural hurdles that inflation-targeting regimes must overcome to be successful.

2.3. Research Gap and Contribution

While extensive research has examined the inflation–growth nexus and the macroeconomic ramifications of inflation uncertainty, few studies have empirically assessed how inflation uncertainty evolves under inflation-targeting frameworks in emerging economies, particularly in the face of increasing global volatility. The existing literature often focuses either on validating classical theories or analyzing inflation levels in isolation without fully considering how persistent nominal volatility interacts with structural vulnerabilities, policy credibility, and external shocks.

This study addresses this gap by evaluating the long-term performance of Mexico’s inflation-targeting regime from 1995 to 2019, using advanced volatility models (GARCH-M and VAR-BGARCH-M) to estimate the impact of inflation uncertainty on macroeconomic performance. Unlike previous studies that focus on confirming theoretical expectations, this research emphasizes the contextual relevance of inflation uncertainty. It contributes by assessing whether inflation-targeting frameworks remain robust and credible, providing new empirical evidence from a structurally open and externally sensitive economy.

The originality of this study lies in its combined focus on macroeconomic volatility and credibility, offering nuanced insights into the effectiveness of inflation targeting beyond its conventional metrics. The findings carry policy relevance for emerging economies that seek to navigate inflation control while enhancing economic stability in a turbulent global environment.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Variables

This study utilizes high-frequency monthly data spanning the period from 1995 to 2019 to rigorously analyze the relationship between inflation, inflation uncertainty, and economic performance in Mexico. Inflation is operationally defined as the annualized monthly logarithmic difference in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), while economic activity is proxied by the Industrial Production Index (IPI). These indicators are commonly used in the empirical literature to assess short- and medium-term macroeconomic fluctuations. The choice of high-frequency data enables a detailed examination of volatility dynamics and transmission effects across macroeconomic variables (

R. M. Grier & Grier, 1998;

Perrotini Hernández & Rodríguez Benavides, 2012). To ensure methodological robustness and statistical validity, various econometric techniques are implemented to model inflation and its uncertainty. Specifically, Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (GARCH) models and Vector Autoregressive (VAR) frameworks, in conjunction with multivariate GARCH structures, are estimated to capture the intricate interplay between inflation dynamics, uncertainty propagation, and macroeconomic volatility.

3.2. Empirical Strategy

To capture the time-varying nature of inflation and its associated uncertainty, we apply an ARMA-GARCH-in-mean (ARMA-GARCH-M) model. This model structure allows for the simultaneous estimation of inflation volatility and its feedback into inflationary dynamics, offering insights into how perceived uncertainty may shape inflation behavior over time, in accordance with the methodology developed by

Engle et al. (

1987) and subsequently applied to inflation dynamics by

R. M. Grier and Grier (

1998). The inclusion of a structural break variable reflects the adoption of the inflation-targeting framework, enabling a comparison of inflation uncertainty dynamics before and after the regime shift.

Furthermore, to evaluate the interaction between inflation, uncertainty, and real economic performance, we employ a bivariate VAR-GARCH-in-mean (VAR-BGARCH-M) framework. This model integrates the temporal interdependence of inflation and output with their respective volatility processes, enabling an assessment of how uncertainty in inflation propagates through the economy. A multivariate BEKK parameterization is used to capture the conditional variance–covariance structure, which facilitates the identification of volatility spillovers and persistence effects.

3.3. Model Structure and Interpretation

While this study acknowledges the existence of potential nonlinearities in the relationship between inflation, uncertainty, and economic growth, as suggested by the threshold and regime-switching literature, it opts for a GARCH-M and VAR-BGARCH-M modeling approach for the following reasons. First, these models are particularly well suited for capturing time-varying volatility, volatility clustering, and feedback effects, all of which are empirically observed in macroeconomic time series. Second, incorporating conditional variances into the mean equations facilitates the estimation of the direct impact of uncertainty on macroeconomic outcomes while avoiding the need to impose thresholds or rely on pre-specified regime structures, as is sometimes necessary in threshold or regime classifications. Third, the BEKK-GARCH specification adopted in the multivariate context provides a flexible framework for modeling dynamic interdependencies and volatility spillovers between inflation and output, which are essential to understanding the transmission mechanisms in emerging economies. We acknowledge that threshold-based or regime-switching models could offer additional insights, but the chosen framework strikes a balance between interpretability, robustness, and data requirements and is well established in the literature for analyzing inflation uncertainty.

The univariate ARMA-GARCH-M model used to estimate inflation uncertainty and its feedback effect on inflation is specified as follows:

The formal specification of the model is given by

where

represents the inflation rate at time t.

denotes the conditional variance of inflation, serving as a proxy for inflation uncertainty.

quantifies the impact of inflation uncertainty () on inflation dynamics.

is an error term characterized by zero mean and conditional variance .

and capture the persistence characteristics of inflation uncertainty.

evaluates the effect of lagged inflation on its uncertainty.

measures the structural shift in inflation uncertainty following the implementation of an inflation-targeting regime.

The bivariate VAR-BEKK-GARCH-M model is formulated to assess the joint dynamics between inflation and output, incorporating their respective conditional variances into the mean equations.

The VAR model is formally expressed as follows:

where

is a vector comprising inflation () and economic growth ().

B represents a matrix of structural coefficients.

C denotes a vector of constant terms.

represents coefficient matrices that encapsulate the dynamic interactions between inflation and economic growth.

is a vector of stochastic error terms with zero mean and a conditional variance–covariance matrix .

The optimal lag length p for the VAR system is determined by minimizing the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Schwarz Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).

To rigorously model the volatility dynamics of inflation and economic growth, a multivariate GARCH model in its BEKK parameterization (

Engle & Kroner, 1995) is employed. This specification allows for an asymmetric and flexible representation of conditional variances and covariances, enabling the identification of spillover effects between inflation and economic activity.

The BEKK representation is given by

where

denotes the conditional variance–covariance matrix of inflation and economic growth.

is a lower triangular matrix of constant parameters, ensuring positive definiteness.

and are coefficient matrices capturing the transmission of past shocks and persistence in volatility, respectively.

The coefficients within quantify the impact of previous innovations on the current conditional variance, while those in reflect the degree of persistence in volatility dynamics. This formulation allows for the empirical assessment of cross-market volatility spillovers between inflation and economic growth.

3.4. Impact of Inflation Uncertainty on Economic Growth

To assess whether inflation uncertainty significantly influences economic performance, the conditional variance of inflation

is explicitly incorporated into the mean equation of the VAR model:

where

is a vector of constant terms.

represents a coefficient matrix capturing the effect of inflation uncertainty on inflation and economic growth.

is the vector of conditional standard deviations associated with inflation and economic growth.

The complete system can be structured as follows:

These model specifications provide a flexible structure for capturing volatility clustering, feedback effects, and spillovers in a high-frequency macroeconomic setting. The modeling framework is designed not only to estimate statistical relationships but to provide a structured lens through which macroeconomic uncertainty can be analyzed in an emerging-market context. By incorporating conditional variances directly into the mean equations, we are able to quantify the influence of inflation uncertainty on macroeconomic performance over time. The use of high-frequency volatility models is especially pertinent in environments characterized by policy shifts, global financial turbulence, and inflationary shocks.

This approach enables us to evaluate how effective Mexico’s inflation-targeting regime has been in promoting price stability and mitigating the adverse effects of uncertainty on real economic variables. The goal is to generate empirical evidence that informs policy discussions and enhances our understanding of the transmission mechanisms linking monetary regimes to economic resilience.

3.5. Model Diagnostics and Robustness

To ensure the validity and robustness of the estimated model, the following diagnostic tests are conducted:

Residual Autocorrelation: Ljung–Box test and Breusch–Godfrey test.

Heteroskedasticity:

Engle’s (

1982) ARCH test to detect conditional heteroskedasticity in residuals.

Stationarity of Series: Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and KPSS tests to assess unit root properties.

Model Fit Evaluation: Comparison of Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Schwarz Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for optimal lag selection.

It is important to acknowledge certain methodological limitations inherent in the use of GARCH-type models. While the adopted framework is effective for modeling volatility dynamics and capturing feedback effects over time, it does not explicitly address potential endogeneity concerns. While the model does not fully address endogeneity concerns, including reverse causality and omitted variable bias from external shocks, these issues are acknowledged as potential limitations and suggest directions for future research. Our aim, however, is not to identify structural causality but to provide a dynamic description of volatility interactions and their macroeconomic implications in a highly open and shock-prone emerging economy. The use of high-frequency data and lag structures helps to mitigate, although not eliminate, some endogeneity risks.

4. Results and Discussion

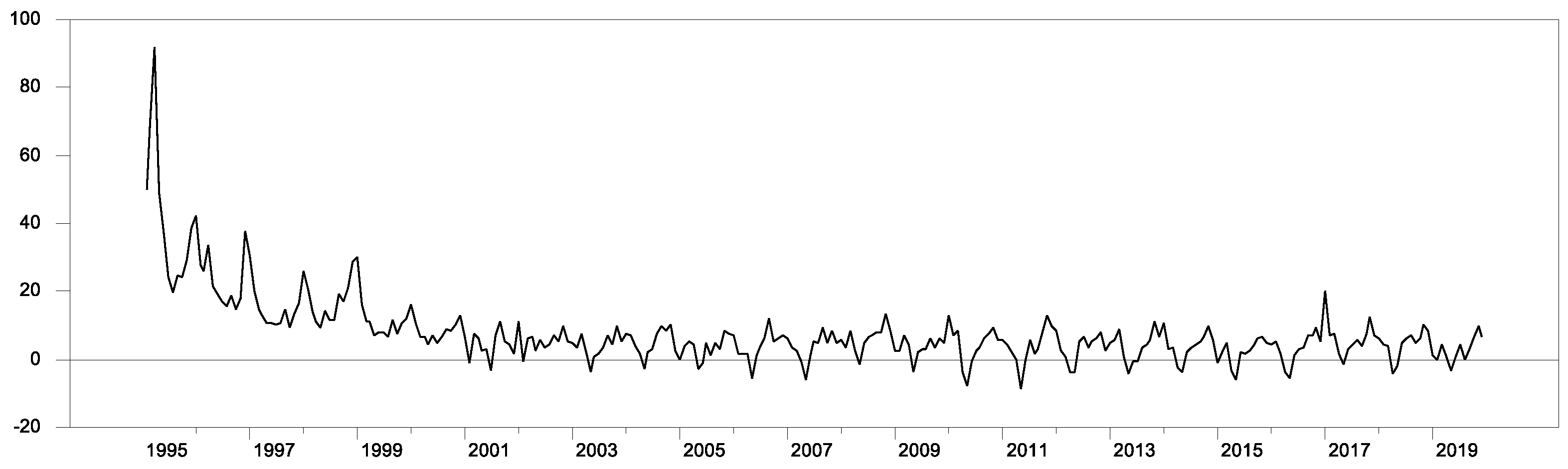

Figure 1 illustrates that, following the adoption of a flexible exchange rate regime in 1995 and the implementation of inflation targeting—measured as the annualized monthly difference in the logarithm of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), defined as

this variable exhibits a downward trend and greater stability, particularly after 2003. Conversely, the economic output variable, measured as the annualized monthly difference in the logarithm of the Industrial Production Index (

IPI), defined as

shows an opposite pattern.

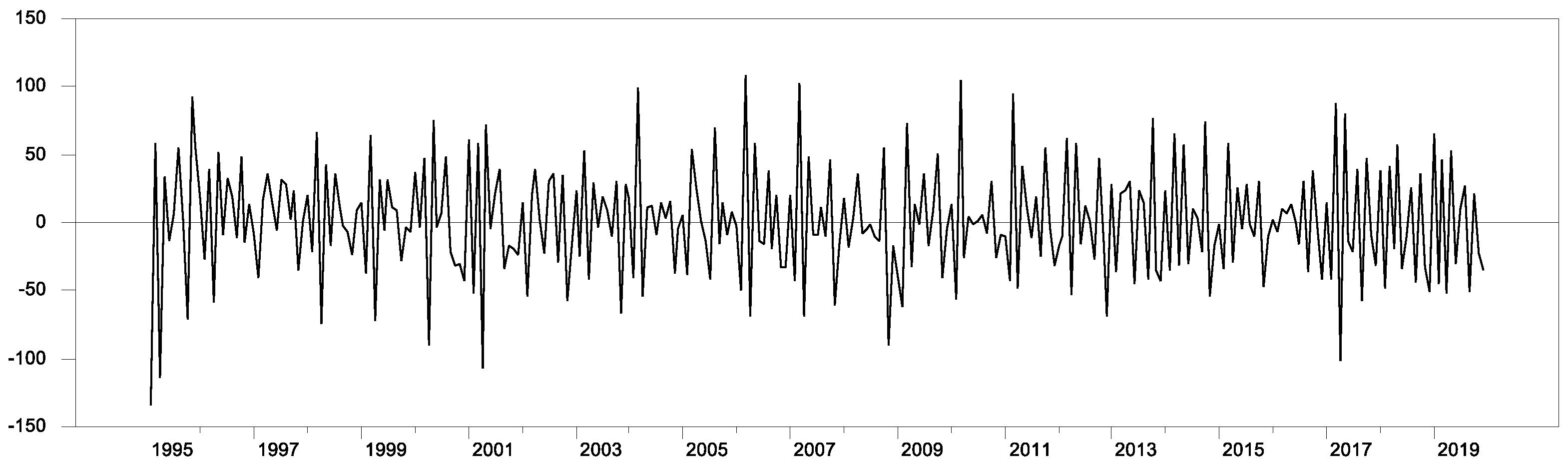

Figure 2 demonstrates markedly different behavior from inflation, characterized by episodes of heightened volatility, especially after 2001. Both variables exhibit heteroskedastic behavior, making them suitable candidates for an ARCH effect analysis, as proposed in the previous section.

To verify whether the transformed series exhibit unit root properties, the Dickey–Fuller test (

Dickey & Fuller, 1979) and the Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin (KPSS) test (

Kwiatkowski et al., 1992) were conducted. The results are presented in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3. The findings indicate that the series do not exhibit unit roots and are thus integrated of order zero, I(0). Both tests were applied under different specifications (with intercept

and with trend

), yielding consistent results.

Table 4 presents an inflation model incorporating 13 lags of inflation as explanatory variables, along with a variable representing our measure of uncertainty, which is derived from the variance equation, following the approach of

K. B. Grier et al. (

2004). Additionally, the Ljung–Box test statistics for residuals and squared residuals are reported, indicating that the model has successfully addressed issues of serial correlation and ARCH effects.

The model estimation is conducted using the quasi-maximum likelihood (QML) method proposed by

Bollerslev and Wooldridge (

1992), which corrects standard errors in the presence of non-normal residuals.

The estimation results reveal a statistically significant and positive association between inflation and its conditional variance, indicating that periods of higher inflation are characterized by greater inflation uncertainty. The estimated coefficient is 0.40, with a t-statistic of 4.77, suggesting a robust link between these two variables in the observed context.

In contrast, the estimated effect of inflation uncertainty on average inflation is positive but not statistically significant, with a coefficient of 0.10. Similarly, the adoption of the inflation-targeting regime is associated with a negative coefficient of −0.09, which does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance. These findings highlight the asymmetric and context-dependent nature of the relationships among inflation, uncertainty, and policy frameworks.

R. M. Grier and Grier (

1998) conducted a similar study for the period 1960–1997, finding a coefficient of 2.79.

Effects of Uncertainty on Inflation and Economic Performance

This section presents the results of the VAR bivariate GARCH-in-mean (VAR-BGARCH-M) model, which enables an assessment of the effects of uncertainty on inflation and economic performance. Similar to the previous model, estimating this model requires verifying whether the series exhibit serial correlation and heteroskedasticity in the residuals. The results, available in

Table 5 and

Table 6, indicate the presence of serial correlation and ARCH effects, demonstrating that the variance of inflation and output is not constant over time. The model was estimated using 12 lags in the mean equation.

To ensure proper model specification, several diagnostic tests were conducted, as described below:

There is significant conditional heteroskedasticity in the data. Homoskedasticity would require the coefficients of matrices

and

(

Table 7) to be jointly insignificant. However, our test indicates that both matrices are jointly significant at the 1% level.

The hypothesis of a diagonal covariance structure requires that the diagonal elements of matrices and be insignificant. In our model, the test results are significant at the 1% level, suggesting that the lag of variance and squared residuals of inflation (or output) tend to affect the conditional variance of the other variable (inflation or output).

Finally, the joint significance of the coefficients in matrix indicates the presence of GARCH-in-mean (GARCH-M) effects.

The conditional mean equation is specified as follows:

where

The intercept vector

and lag matrices

to

are given by

In the inflation equation, most of the coefficients were small, with both positive and negative values, and were significant in some cases. The effects on inflation were only significant at the first, ninth, and twelfth lags, all showing positive signs. In summary, these effects, although short-term, indicate that the response to shocks in both variables is dynamic and predominantly oscillatory.

The parameter yielded a positive coefficient of 0.37 with a t-statistic of 1.00, indicating a non-significant relationship between inflation uncertainty and output growth in this context. In contrast, showed a negative coefficient of −2.34 and a t-statistic of −1.82, suggesting that increased inflation uncertainty is associated with lower economic growth effects, consistent with the findings in the broader empirical literature.

Regarding the effect of output uncertainty on inflation, the estimated coefficient

was −0.16, indicating a weak and negative association. This result contrasts with earlier work by

Devereux (

1989) but is more aligned with studies emphasizing central bank behavior under uncertainty, such as those by

Cukierman and Meltzer (

1986). Lastly, the coefficient

, which captures the effect of inflation uncertainty on the average level of inflation, was estimated at 0.93 and found to be statistically significant at the 10% level, supporting the view that uncertainty may contribute to higher inflation outcomes in certain environments.

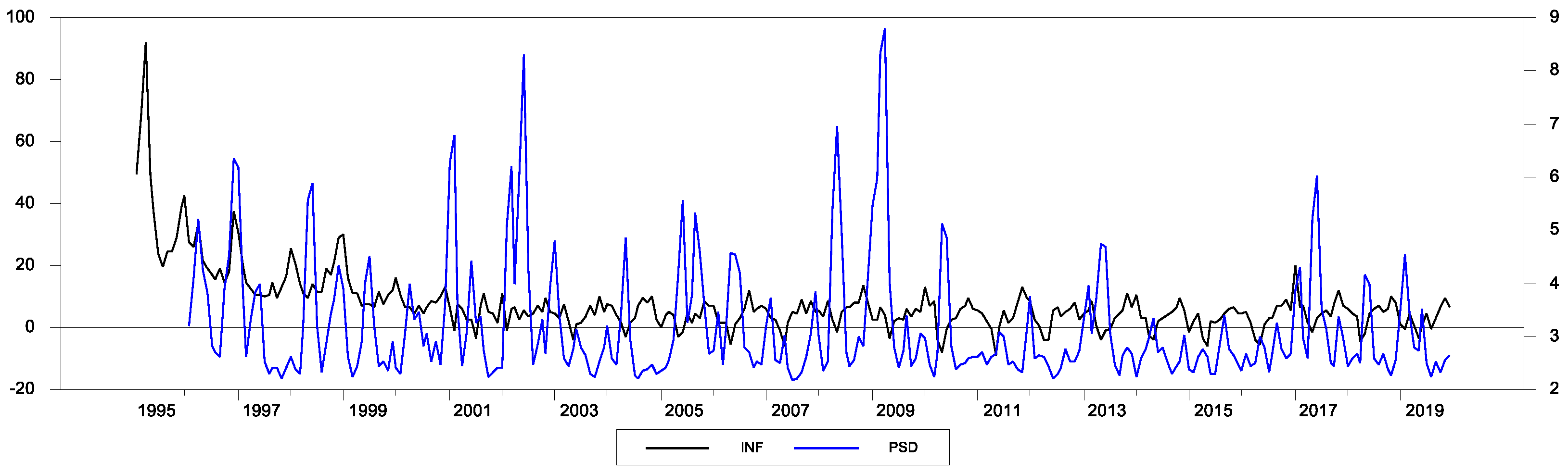

A useful tool in the estimation of GARCH models, as employed by

Engle (

1982), is to plot the conditional variance alongside the variable of interest. The purpose of this exercise is to contrast the behavior of the variable in levels over time and determine whether the effect of uncertainty (measured by variance) follows the same historical trend.

In this study, we provide a comparison between the standard deviation

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 of inflation and output alongside their respective level series. The standard deviation is estimated from 1996 onward due to the lags incorporated in the estimation of the GARCH model.

In the case of the inflation rate, the standard deviation effectively captures the periods of crisis experienced by the Mexican economy during the study period. Notably, the economic slowdown in 2001 led to increased uncertainty regarding future price levels, while the 2008 financial crisis marked the highest standard deviation observed in the sample. A similar pattern is observed for output, with heightened standard deviations in both 2001 and 2008. From 2009 to 2017, a period of lower volatility is evident, followed by a significant increase from 2017 onward.

5. Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between inflation, inflation uncertainty, and macroeconomic performance in Mexico, with a particular focus on the role of price volatility in shaping the dynamics between inflation and economic growth. The empirical results point to a positive and statistically significant association between inflation and its conditional variance, underscoring that greater price uncertainty constitutes a measurable cost of inflation. Moreover, the analysis reveals that higher inflation uncertainty is associated with lower economic growth, highlighting its potential adverse macroeconomic effects.

Contrary to the expectations commonly associated with inflation targeting (IT) regimes, the evidence does not indicate that the adoption of this monetary framework in Mexico has led to a significant reduction in inflation uncertainty. While the Bank of Mexico has achieved notable success in stabilizing inflation levels, the persistence of a strong correlation between inflation and its uncertainty suggests that the IT regime has not fully mitigated the destabilizing effects of volatility on economic activity.

Another important finding relates to the interaction between output uncertainty and inflation. The results suggest that economic growth volatility exerts a negative, although modest, influence on inflation, partially aligning with earlier theoretical perspectives. However, the evidence does not support a statistically significant effect of output uncertainty on the overall macroeconomic performance, which calls into question generalized assumptions about the long-term impact of real volatility on growth in emerging-market contexts.

Policy Implications

This study offers key policy insights for emerging economies operating under inflation-targeting regimes. First, the results highlight the importance of going beyond the pursuit of inflation targets to explicitly address inflation uncertainty. Volatility in inflation undermines investment and economic confidence, requiring central banks to strengthen forward guidance, enhance communication strategies, and regularly publish inflation risk assessments to bolster policy credibility and manage expectations more effectively.

Second, monetary policy should be complemented by coordinated fiscal and structural measures. Governments could implement stabilizers, such as countercyclical spending programs or targeted subsidies, during inflationary or recessionary periods. Additionally, reforms that promote labor market adaptability and improvements in financial intermediation would help to absorb shocks and support long-term growth. Greater labor market flexibility can act as a buffer in the presence of inflation uncertainty by enhancing the economy’s adaptability to changing cost and demand conditions. Increased volatility in inflation can generate planning difficulties and discourage long-term investment. In rigid labor markets, such uncertainty may lead firms to delay hiring or reduce activity due to higher adjustment costs. In contrast, more flexible labor frameworks—through adaptive contracts, efficient resource reallocation, and lower wage rigidities—can help firms to respond more smoothly to unexpected price movements. This can reduce the economic friction associated with volatility, allowing growth to continue even amid uncertain inflation dynamics.

Third, the current global context—marked by external shocks, geopolitical tensions, and rising imported inflation—calls for more adaptive and resilient policy frameworks. Inflation-targeting regimes should incorporate mechanisms to monitor external price pass-through effects. Coordination with fiscal authorities in times of imported inflation can also facilitate targeted support to affected sectors while preserving monetary credibility.

Finally, policymakers should balance price stability with broader objectives, such as inclusive growth and financial stability. A broader conceptualization of macroeconomic stability that includes managing inflation uncertainty will better equip economies like Mexico to navigate a complex and interdependent global environment.