1. Introduction

Given the growing number of forcibly displaced persons (FDPs) internationally and nationally, the problem of forced displacement has become a major concern for both social and public policy. The

UNHCR (

2024a) report on global trends estimates that 117.3 million people had been forcibly displaced worldwide at the end of 2023, with a population of 122.6 million people being under UNHCR protection and/or assistance (

UNHCR, 2024a). This displacement is a result of conflict, violence, climate-related effects, human rights violations, ethnic and religious intolerance, and the poor management of public affairs, among other sociopolitical issues (

UNHCR, 2021). Eighty-five percent of the forcibly displaced population is hosted in low- and middle-income countries (

UNHCR, 2021;

Zademach et al., 2019). Kenya alone hosted 691,868 refugees by the end of 2023, which increased to 823,923 by 2024 (

UNHCR, 2023,

2024b). Of this population, the UNHCR supports 274,816 of Kenyan registered refugees and asylum seekers (

UNHCR, 2023).

Despite interventions by the international community and other non-governmental organizations regarding humanitarian assistance to host countries, the huge population of forcibly displaced persons overwhelms such efforts, forcing hosting governments to grapple with numerous challenges associated with the stabilization and settling of displaced persons (

Verme & Schuettler, 2021). It is commonplace for humanitarian agencies to put efforts into organized FDP camps, paying less attention to long-term displaced residents in the broader community who are also grappling with competition for resources and opportunities.

Kenya, which shares borders with nations beset by ethnic conflicts, internal disturbance, and economic and environmental degradation, attracts asylum seekers from neighboring countries. With over half a million refugees and asylum seekers who have been displaced for long periods, Kenya hosts refugees from Somalia, South Sudan, Ethiopia, DRC, Burundi, Uganda, and Sudan. Most refugees are concentrated in the Dadaab, Kakuma, Kalobeyei, and Nairobi camps. Kenya is among the few African countries with an asylum regime that has been flexible and accommodating. However, in recent years, Kenya’s asylum regime has undergone substantial changes in its policy framework and management practice due to changing security dynamics (

Kiama & Karanja, 2012).

Refugees in Kenya experience various socioeconomic challenges in their efforts to survive, considering the limited resources that must be shared between them and the host community members. For instance, refugees in Kenya are often placed in remote desert camps, where their mobility and access to employment are restricted, forcing them to find survival strategies to overcome multiple challenges and obstacles. Entrepreneurship and self-employment offer an approach to meeting their objectives. However, for self-employment to yield results, technical support and entrepreneurship training, market access, and finances may be required, which presents refugee challenges regarding access and use.

Evidence has shown that refugees can contribute positively to the host economy if allowed to pursue livelihoods, integrate socially, and be financially included (

Zademach et al., 2019). Some research has portrayed formal financing as playing a role in supporting refugees in their economic endeavors (

Anderloni & Vandone, 2018); it has been argued to help them integrate into the local economy and society, promoting self-reliance, economic independence, and social inclusion. Other researchers have, however, argued that there is no rationale for refugees to use financial services to save or invest since financial services can only marginally improve their lives (

Dhawan et al., 2022;

Dhawan, 2022).

Dhawan and Zollmann (

2023) further claim that the financial services provided for FDPs are not meant to empower but rather to isolate and limit refugees’ transactions, thus effectively excluding them.

Bhagat (

2022) and

Krause and Schmidt (

2020) also argue that self-reliance transforms refugees into disposable subjects in capitalism at various stages of the asylum process and aids the power of humanitarian agencies over the refugees.

While research on financing refugees for self-employment has grown in recent years, exploring the potential synergies and challenges of integrating formal and informal financing mechanisms for refugee self-employment is necessary. Understanding how formal financial institutions can collaborate with informal lenders, saving groups, and community-based organizations to provide comprehensive and sustainable financial support will be crucial; this study aims to fill this gap in the literature by investigating the contribution of formal and informal finance to self-employment among urban refugees in Kenya and assessing the determinants of financing choice and self-employment. This will hopefully spur more investigation into the barriers that hinder FDPs from accessing formal financing to allow financial institutions to design products that can meet these unique needs, explore mechanisms that bridge the gap between formal and informal financing channels, and leverage the strength of both.

More work is needed to provide insights into whether policymakers should advocate for financing refugees and, if financing is needed, which form should be encouraged. Using an extension of the

Oaxaca (

1973) decomposition by

Fairlie (

2014) and other descriptive statistics, this study dives into the 2021 Socioeconomic Survey of Urban Refugees in Kenya to provide more evidence on the impact of formal and informal finance on self-employment. To attain these objectives, this study answers the following questions: (a) Other than financing, what factors influence the decision to choose self-employment among refugees? (b) What are the contributions of formal and informal financing towards self-employment among refugees?

1.1. Formal vs. Informal Financing

Financing sources can be formal or informal. Formal financing refers to financial resources acquired through official channels, such as banks, financial institutions, credit unions, or other regulated financial intermediaries; these often require formal applications, documentation, and collateral. In contrast, informal financing includes financial resources that are acquired outside of the formal financial channels, primarily those provided by relatives, friends, and informal groups and associations, without the requirement of formal documentation and collateral (

Ayyagari et al., 2010;

Guirkinger, 2011;

Hou et al., 2020;

Nguyen & Canh, 2021).

The distinction between formal and informal financing is the legal and regulatory frameworks that govern their operations. Government authorities usually monitor and regulate formal financing, while informal financing operates outside formal regulations (

Degryse et al., 2016;

Karaivanov & Kessler, 2018). Additionally, formal financing is more structured, with standardized terms and conditions, while informal financing is often flexible, with less formal agreements, and may vary substantially regarding interest rates and repayment schedules. Even though formal financing may be more affordable and long-term, it may require collateral, credit history, and legal documents such as national identity cards, which may be lacking among FDPs (

Turkson et al., 2022). Since FDPs tend not to have tangible assets as collateral, lenders often consider them high risk. Cultural and religious norms about credit and interest hinder FDPs from accessing formal credit sources. As a result, FDPs often rely on informal financing structures, which tend to be risky and exploitative.

1.2. Progress on Refugee Financial Inclusion in Kenya

There has been substantial progress in the provision of financial solutions to refugees. In collaboration with local banks and microfinancial institutions, the international community has been exploring formal financing modalities that work for refugees, considering their documentation and other financing-related challenges (

Cheruto, 2024). For instance, the International Rescue Center (IRC) supports a project that provides small loans to refugees to start businesses (

Rebuild, 2017). RefugePoint also has an initiative that enables refugees in Nairobi to open bank accounts with Postbank; this enables business grants to be deposited directly into their accounts, along with rent assistance and emergency aid (

RefugePoint, 2021). These savings accounts help refugees become self-reliant by building a financial history to access formal credit. The International Finance Corporation has also initiated a risk-sharing facility with equity banks to provide financial services to refugees (

Abdalla, 2024). However, refugees’ heterogeneity, regarding their varied economic and professional backgrounds, religion, gender, age, and other demographics, calls for different financial solutions to address their needs.

In addition, Bamba Chakula, which is a cash-based intervention designed by the World Food Program (WFP) in collaboration with Safaricom, as an alternative to the in-kind food aid cash program, enables refugees to start their businesses, register the businesses with the program, and, thus, generate income by trading (

Betts et al., 2018;

WFP, 2015;

UN-WFP, 2016). Many refugees who have taken advantage of this program are self-reliant in settlement camps, running thriving businesses, selling to fellow refugees, and benefiting from monthly Bamba Chakula programs (

Betts et al., 2018). Within the same camps, however, are poverty-stricken families relying mainly on cash transfers (

Betts et al., 2018); this calls for financial solutions that can serve these differing groups of the displaced population, uplifting the living standards for all.

Few financial institutions serve the needs of refugees. Some equity bank branches allow camp-based access to open bank accounts. Even though the digital financial market is highly developed in Kenya, refugees do not have full access to these services since they cannot directly access regular M-Pesa wallets (mobile money). Mobile money is only limited to those with Kenyan identity documents. Refugees have locked wallet accounts (Bamba Chakula) designed for the WFP to distribute cash for food items in select stores within the settlement camps (

Betts et al., 2018).

The UNHCR, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), and the ILO have developed joint programs to support financial service providers in providing affordable financial services to refugees (

Abdalla, 2024). Unfortunately, only a handful of financial service providers have considered extending their services to refugees. Also, concerns about money laundering and terrorism financing have made financial providers cautious, enacting strict rules that hinder FDPs from accessing financial services. Without adequate access to such financial services, refugees lack avenues to address their financial needs and sustain their livelihoods (

Singh, 2023).

2. Literature Review

Migration decisions for the FDPs are not the result of choice; involuntary displacement comes from the sudden shock (

Verme & Schuettler, 2021). FDPs mainly consider proximity, networks, and security criteria whenever they move. Their main objective is to satisfy their basic needs and ensure a brighter future for themselves and their children, mostly through education and better health (

Rwamatwara, 2009). However, FDPs usually settle in remote and poor communities where competition for these basic amenities is already high (

Mugisha & Siraje, 2023;

Turkson et al., 2022). Locals may view FDPs as people who have come to take away their resources, thus creating conflicts (

Rwamatwara, 2009).

Research has shown how the influx of FDPs affects host countries concerning increasing unemployment (

George & Adelaja, 2021). Forced migration also causes labor supply shocks by reducing real wages for urban unskilled workers who compete for jobs with forced migrants (

Calderon & Ibanez, 2009). According to

Ruiz and Vargas-Silva (

2013), this effect is usually greatest in the informal sector, leading to commodity price increases. Other researchers argue that forced displacement results in economic shocks through the influx of population and increased expenditures due to mass movement and concentration in camps (

Fiala, 2015). The expenditure shock results occur because once the forced migration occurs, humanitarian agencies release aid to the host countries, supplementing the savings held by the FDPs, thus increasing demand and purchasing power, affecting expenditure (

Verme & Schuettler, 2021). Ultimately, this creates jobs through increased demand for goods and services, new enterprises develop, and sales increase.

The issues of FDPs have always been perceived as a temporary problem that requires temporary solutions. However, recently, it has been noted that refugees tend to be stuck in host countries for an average of 26 years (

UNHCR, 2021;

Omata, 2021). Considering the length of time that FDPs take to successfully manage to return to their home countries after crises, providing basic needs is not sustainable for the humanitarian agencies in the long run (

Kachkar, 2017). Taking note of the fact that over 85 percent of the refugees settle in developing countries, which are also battling developmental challenges such as employment, there is a need to establish more ways of improving livelihoods, integrating FDPs into the local community, and expanding their social networks (

Kachkar, 2017). In order to avoid building a culture of dependency among FDPs, especially when basic needs are all provided, it has been advocated that they be engaged in economic activities in either agriculture or business (

Ruiz & Vargas-Silva, 2013).

Financial inclusion through opening bank accounts, as one of the UNHCR’s key priorities, promotes self-employment among refugees and stimulates economic activity (

Mugisha & Siraje, 2023). A focus on the European context identifies access to finance as a significant factor affecting refugees’ ability to engage in entrepreneurial activities and calls for more targeted support mechanisms (

Brzozowski & Voznyuk, 2024).

Newman et al. (

2024), in their analysis of the factors influencing refugees’ entrepreneurial activities, emphasize the critical role of financial resources in enabling refugees to start and sustain businesses while identifying barriers such as limited access to formal financing channels. In addition,

Heilbrunn and Iannone (

2020) also discuss the importance of financial capital for refugee entrepreneurs and highlight the challenges they face in accessing funding due to legal and institutional constraints.

In Kenya, few refugees engage in income-generating activities since most are employed by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as incentive workers with pay restrictions (

Betts et al., 2018). Formal credit for refugees is one of the dignified ways to improve their ability to generate income through self-employment. Many households may be willing to be involved in agriculture or do business but lack resources like sufficient water and seeds for agriculture and capital for conducting business. While looking at self-reliance in Kalobeyei,

Betts et al. (

2018) found that many residents suffered due to a lack of economic activities at the camps and their surroundings. The Kalobeyei settlement aimed to transition refugees from aid dependence to self-reliance and integrate them with the host communities through the Kalobeyei Integrated Social and Economic Development Program (KISEDP). However, this aim was not fully actualized due to the influx of South Sudanese refugees, who still needed emergency assistance (

Betts et al., 2018).

Most FDPs are equipped with entrepreneurial marketable skills that can be exploited to earn some income. These skills can be utilized to improve their livelihoods, but in most circumstances, these skills are not exploited (

de Lange et al., 2021). According to

Kachkar (

2017), refugees can actively engage in income-generating activities that improve their socioeconomic situation.

Kachkar (

2017) advocates for establishing microfinance and start-up funds to promote entrepreneurship among refugees in refugee camps and urban areas, noting that the charitable institution of waqf (endowment) can be used to develop a sustainable model to promote the economic engagement of refugees. For instance, the Bamba Chakula program by the WFP provides opportunities for refugees to trade amongst themselves; this is a cash program, which implies that refugees can start their businesses, register them with Bamba Chakula, and thus generate income by trading amongst themselves (

Betts et al., 2018).

Studies in Kenya’s Kakuma camp have shown a thriving informal economy, with opportunities in clean energy products, waste management and recycling, sanitation, vegetable and fruit value chains, and other necessary items (

Kibuka-Musoke & Sarzin, 2021). However, most of the businesses are owned by Kenyan residents because the refugees lack the necessary capital to establish such enterprises. They also lack education, skills, and talents to use as business owners or employees. According to

Kibuka-Musoke and Sarzin (

2021), financial literacy is also low among refugees, making access to finance challenging. Town residents are more likely to receive credit than those in camps. The refugees lack relevant information on available financing opportunities.

Language barriers also pose a huge challenge to refugees’ access to financial services, as financial service providers employ only locals who cannot communicate with the refugees. The inability to communicate with staff at these institutions prevents refugees from accessing the necessary services.

Anderloni and Vandone (

2018) argue that some fail to access financial services due to self-imposed barriers such as distrust of financial service providers. Instead of dealing with local banks, some refugees decide to make all their transactions in cash or save with money guards (people who keep money safe for individuals). According to

Anderloni and Vandone (

2018), this distrust may be self-imposed; it is an individual choice, not circumstantial. Therefore, there is a need to sensitize FDPs to gain the trust of established financial providers.

The location of financial providers also acts as a barrier to accessing financial services. Most banks are located in towns, while refugee camps, especially in Kenya, are in remote areas in the country’s northern parts (

Anderloni & Vandone, 2018). Traveling to access these services thus represents a large cost to FDPs. In addition, refugees tend to require small amounts of credit to establish small businesses. From a business/profit perspective, banks cannot meet their fixed costs with such small loans and are not incentivized to serve these populations.

Studies performed in the USA have shown that immigrant entrepreneurs often rely on a single source of financing—more specifically, informal or bootstrapping, whereby they tend to avoid equity financing (

Moghaddam et al., 2017).

Gachoka and Merab (

2021) investigated financial sources that refugees use in Kenya and Uganda and found that 40% of households source their income through self-employment. Saving groups have been established for the informal borrowing and receipt of remittances. Since the FDPs are considered high-credit risk customers by formal financial providers, the refugees often form groups that regularly contribute an agreed amount of money and save. Once these savings are sufficient, the refugee group members borrow amongst themselves and repay their debts with interest. Some saving groups receive formal financing from financial providers and then lend this to group members. There is an opportunity for financial service providers to design innovative products and services to cater to the needs of the FDPs through these social groups.

The need to stimulate entrepreneurship among FDPs has been articulated in the

UNCTAD (

2018) policy guide. The major hindrance has always been the temporary status of FDPs in host countries, which limits their opportunities and rights (

de Lange et al., 2021). Pull and push factors facilitate the opportunity and necessity to engage in entrepreneurship. In addition, factors like gender, age, fear of failure, and an individual’s financial and social capital affect the opportunity to engage in entrepreneurship (

Sahasranamam & Sud, 2016). However, most research focuses on labor integration through wage employment (

S. O. Becker, 2022;

Calderon & Ibanez, 2009;

Rwamatwara, 2009;

Ruiz-Vargas, 2000;

Ruiz & Vargas-Silva, 2016). Since unemployment is still a problem, even with host communities, it is prudent to consider different approaches to the refugees’ problems. It is, therefore, valuable for collaborating partners to present entrepreneurship as one of the solutions by making deliberate efforts to provide financing, which will create an opportunity for FDPs to embrace and thus create employment to improve their livelihoods.

These prior studies emphasize the challenges refugees face, including competition for resources, labor market disruptions, and financial exclusion, focusing more on external interventions by governments and humanitarian organizations. This study, however, shifts the narrative from dependency to agency by reframing refugees as active agents of change capable of shaping their economic futures through self-employment. A country like Kenya, where wage employment is scarce, places refugees at the center of decision-making by exploring how FDPs can actively utilize their entrepreneurial skills, networks, and available resources to co-create sustainable livelihood solutions. The study advances the discussion by examining how refugees can transition to economic self-reliance over extended periods, contributing to local economies while reducing aid dependency. This perspective is crucial in moving beyond the dominant view of refugees as passive aid recipients.

3. Theoretical Background

While nationals are more likely to engage in self-employment due to pull factors such as perceived opportunity, business potential, and supportive financial environments, refugees often engage in self-employment due to necessity-driven push factors such as unemployment, legal barriers to formal employment, and survival needs. Financing is crucial for individuals seeking to become self-employed. Formal financing, such as bank loans, venture capital, and government grants, can alleviate liquidity constraints and provide the necessary capital to start and sustain a business. In contrast, informal financing sources, such as loans from family, friends, community-based savings groups, and personal savings, often play a significant role in supporting entrepreneurs lacking access to formal financial institutions. Both types of financing are vital for enabling self-employment, which drives job creation through direct hiring, the multiplier effect, innovation, and economic diversification.

Local nationals have better access to formal financing mechanisms, including bank loans and microfinance institutions, and benefit from established credit systems, lower perceived risks by lenders, and government-backed initiatives designed to promote entrepreneurship. On the other hand, refugees’ financing decisions are specific due to their diverse challenges, including information asymmetries because of them being in a foreign country and environment, language barriers, legal documentation, gaining trust from the local community, and uncertainty regarding the duration of their stay. Despite their need for financial services, such challenges often limit refugees’ access to formal (bank) financing, even in a well-developed financial system base such as Kenya, resulting in market failure. Informal financing arises as a response to the diverse market failures among these refugees, which constrain households from accessing formal financing through credit, savings, and personal bank accounts (

Kedir et al., 2021).

From the demand side, refugees, especially ethnic minorities, may suffer from cognitive financial constraints, including financial illiteracy and language barriers. From the supply side, ethnic minorities/refugees may face discrimination (

Nguyen & Canh, 2021). Having grown up in the local context, nationals benefit from familiarity with local economic systems and more stable living conditions, enabling them to navigate formal and informal financing mechanisms more effectively.

G. S. Becker’s (

1971) taste-based theory suggests that some economic agents may prefer not to transact with particular sets of people who may not be similar to them due to perceived uncertainty and trust. Information-based theory also argues that lenders may have perceived information about minority groups, believing that they are less productive, less educated, and less capable and thus threaten the lenders’ profitability. (

Nguyen & Canh, 2021) argue that these negative attitudes lead to discrimination, thus depriving minorities of their right to access formal financing.

Some households use neither informal nor formal financing, while others use both. This results from heterogeneous tastes and preferences and, to some extent, income (

Kedir et al., 2021). Formal financing is relatively safe, though costly, while informal financing can be risky, with uncertainty in the payout timing. However, given borrowing constraints due to the lack of collateral or building trust with banks, the early payout from informal financing sources provides the major source of financing for high-yield investment in capital goods and consumer durables for refugees. Capital assets purchased through formal (bank) credit generate higher returns because they are likely to be purchased. However, they also involve higher risk since the loan has to be repaid even with investment failure; in contrast, informal financing involves risk sharing. Thus, formal financing may not preclude informal financing but may co-exist (

Kedir et al., 2021).

According to a study by

Stiglitz and Weiss (

1980), formal lenders have limited information concerning the households, thus resorting to collateral requirements to overcome moral hazard and adverse selection problems. Those lacking collateral may involuntarily be excluded from formal credit, thus resorting to informal lenders with information advantage. Contrary to these theoretical arguments, informal credit may not be a last resort but a matter of choice. Informal credit from family and friends may be less expensive than formal loans and thus is preferred by borrowers. Transaction costs related to formal credit applications may discourage households from seeking such loans. Informal loans can be easier to access since the lenders can access greater information, easing the application procedures and thus generating lower transaction costs; this brings the effective cost of informal loans below the effective cost of formal loans, incentivizing transaction cost-rationed households/individuals to take up informal credit despite their higher interest rates (

Guirkinger, 2011). Informal loans may also be preferred due to risk advantage. When informal lenders have better access to relevant information, they can write more state-contingent contracts than formal lenders and thus become less risky for borrowers (

Kedir et al., 2021).

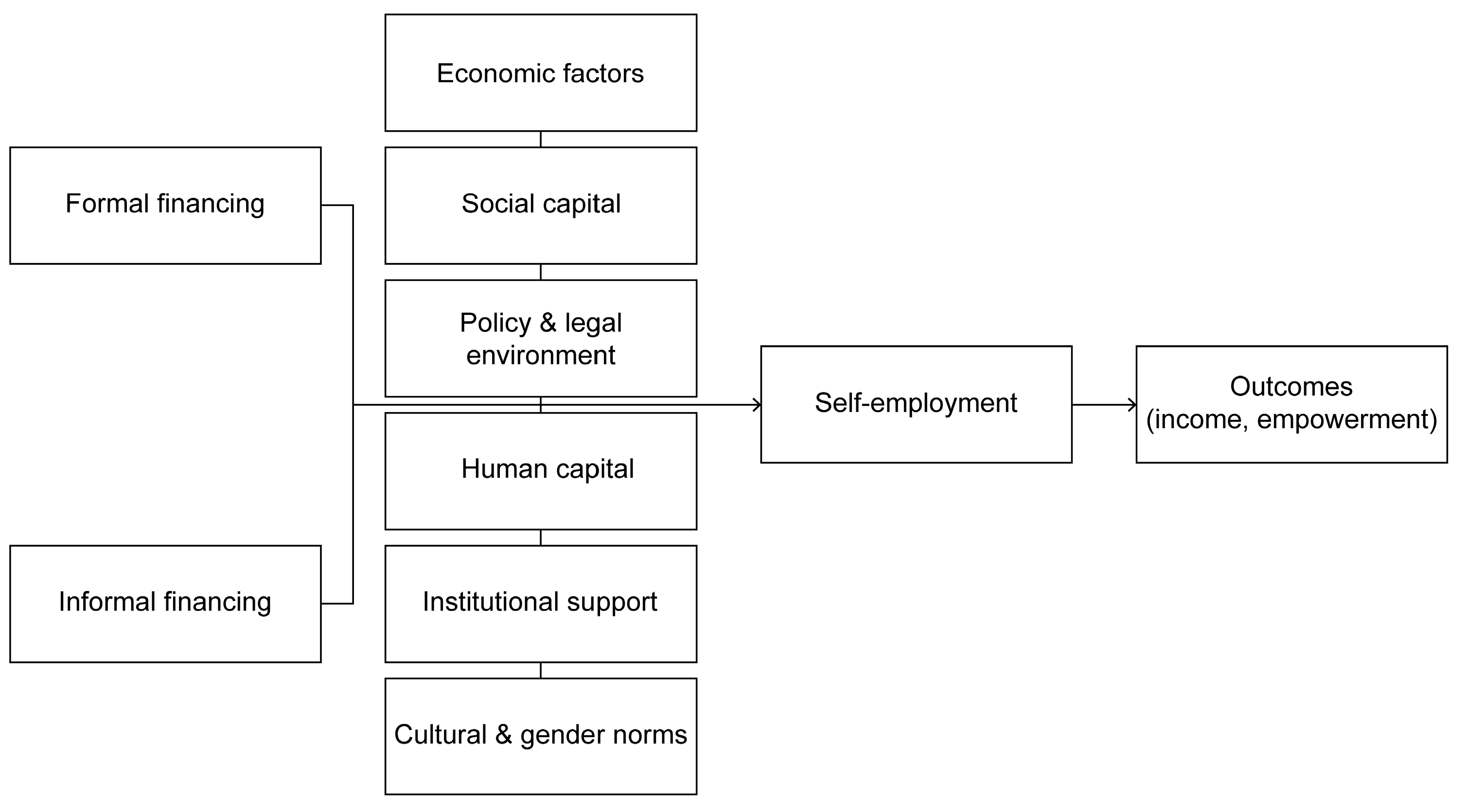

4. Conceptual Framework

Financing plays a multifaceted role in self-employment, influencing everything from the decision to become self-employed to the long-term success and growth of the business.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between financing (formal and informal) and self-employment for refugees, highlighting key intervening factors that influence this relationship and the potential outcomes. Both forms of financing serve as inputs that fuel entrepreneurial activities. The ability to engage in self-employment depends on financing and a range of contextual factors (economic, social, policy, and legal environment, human capital, institutional support, and cultural norms, among other factors).

Formal and informal financing have distinct advantages, limitations, and challenges related to accessibility, affordability, and availability. Given these limitations, refugees rely on financing options that meet their needs or use a hybrid financing model. The effectiveness of financing in promoting refugee self-employment is significantly influenced by other contextual factors that serve as either enablers or barriers to entrepreneurship. For this to be effective, it must be complemented by a supportive policy, economic, and social environment. If financing is supported by favorable intervening factors, self-employment results, income generation, and the empowerment of refugees are achieved.

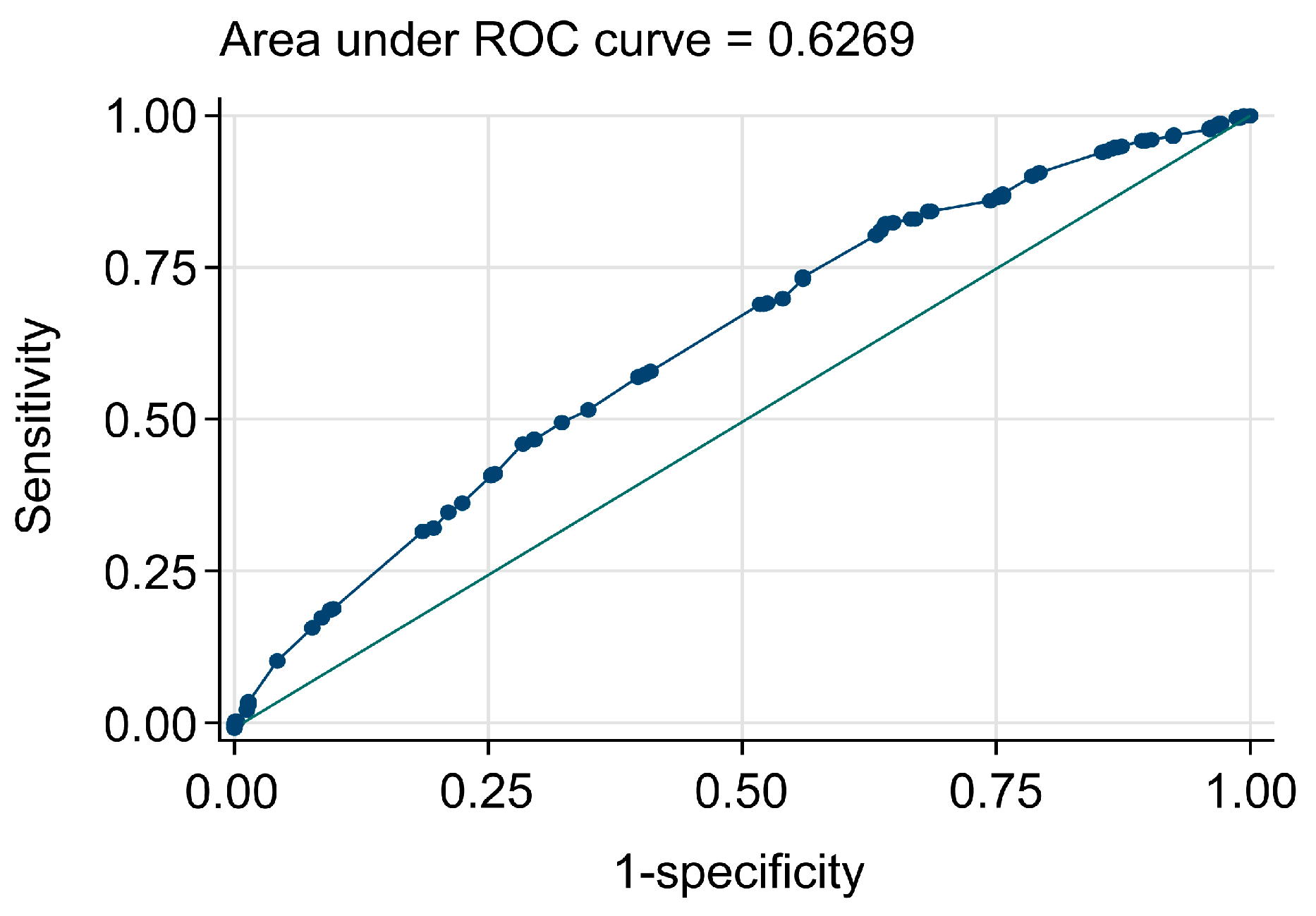

5. Methodology

As the study seeks to investigate the role of formal versus informal finance on self-employment, we first estimate the influence of financing decisions on the choice between self-employment and wage employment among refugees in Kenya. In the modeling, self-employment is coded as 1 and wage employment as 0. The general model being estimated is

where

is self-employment and

is wage employment.

Thus, the logit index for self-employment as a function of financing option is:

where

X represents a set of individual/household characteristics (gender, language, age, literacy, location, refugee status, residence, social capital, and religion) and

is the error term.

The FDPs’ characteristics are not random, and since the data available do not contain information about the immigrants before their move, there is no counterfactual. To quantify the extent to which refugees’ self or wage employment is attributable to the financing type, the study uses the extension of the decomposition method by

Blinder (

1973) and

Oaxaca (

1973), which allows the assessment of how much of the observed differences between the self-employed and the wage earners can be explained by observable factors. In this case, the decomposition methods can split the contribution towards FDPs choosing self-employment, which is explained by the access/use of formal finance and the unexplained component. The same will be performed to assess the portion that can be explained by informal finance and a combination of both.

Since the

Blinder (

1973) and

Oaxaca (

1973) decomposition method assumes a linear regression framework, we cannot use it directly since the outcome variable, self-employment, is binary. In this case, we perform a non-linear decomposition from a logit or probit model as proposed by

Fairlie (

2014), expressed as

where

is the difference in mean outcomes between those using formal financing and those choosing informal financing;

and

represent the sample size for the two groups;

and

represent a row vector of average values of the independent variables for individuals in the two groups; and

and

are vectors of coefficient estimates for financing contribution.

In Equation (3), the first term in brackets represents the part of employment explained by financing source, and the second term represents the part due to differences in the group processes determining the outcome levels. The second term also captures employment due to group differences in unmeasurable or unobserved endowments.

Data Sources and Definition of Variables

This study uses the 2021 Socioeconomic Survey of Urban Refugees in Kenya, which contains data for refugees and nationals. Due to COVID-19 social distancing measures, the data were collected via phone interviews; this may result in some segments of the population missing, such as those without phone access or those who are unwilling to answer calls. However, post-survey weighting has mitigated this to adjust for underrepresented groups. The data include information about the respondents’ financing sourcing for credit and savings. The dataset also has other individual and household characteristics such as age, language, literacy, saving practice, social ties (whether one has relatives and friends in Kenya), community association membership, refugee status (whether a refugee or not), and gender. The study uses this dataset to assess the drivers of refugees’ choices regarding financing decisions and self-employment and the contribution of formal and informal financing towards the likelihood of self-employment.

The financing variable is categorical, formed from whether an individual borrowed money from any listed sources during the past 12 months. Individuals who answered “No” to both formal and informal finance are coded 0, those who answered “Yes” to formal finance are coded 1, those who answered “Yes” to informal institutions, relatives, and friends are coded 2, and those who answered “Yes” to both financing choices are coded 3. In the Fairlie decomposition, the dependent variable, employment status, is coded as 1 if self-employed and 0 if employed with a wage. Other variables used in the modeling are highlighted in

Table 1.

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Refugees’ financing decisions are specific due to their diverse challenges, ranging from information asymmetries due to them being in a foreign country and environment to language barriers and legal documentation. In a well-developed financial system like that of Kenya, one expects access to formal financing to be relatively easy and accessible. However, market failures force individuals and households to choose informal financing to complement and sometimes substitute for formal financing.

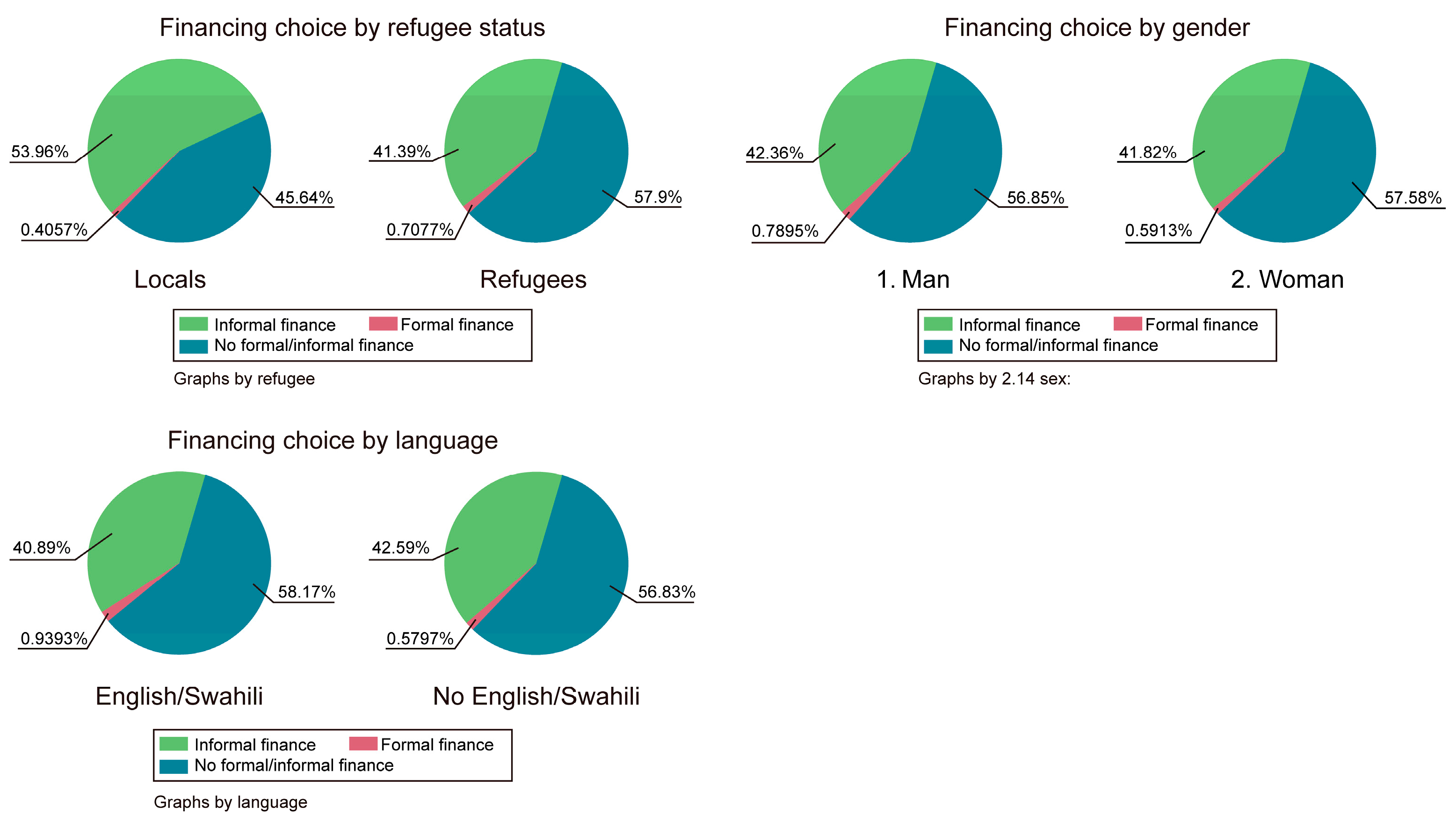

Using data from the 2021 Socioeconomic Survey of Urban Refugees in Kenya, this study sought to investigate the relative contributions of formal and informal finance to the decision to undertake self-employment, with a specific focus on investigating drivers of refugees’ financing decisions and their decision to be self-employed or engage in other wage-paying employment. Findings in this study suggest that financing decisions depend on cognitive characteristics such as refugee status, social capital, ability to communicate in national languages, and supply factors, including the location of the household. On the other hand, the choice to be self-employed is related to financing choice, gender, language(s) spoken, location/residence of the respondent, social ties/capital, saving practices, and education.

As policymakers strive to ensure that refugees access higher education to enhance the creation of jobs, there should also be efforts to offer training to develop fluency in the national and official languages, facilitate their integration into Kenyan society, and provide more employment options. Language training programs that enhance refugees’ and non-native speakers’ command of national languages can improve their employment prospects and business networking. In addition, courses specifically aimed at the language skills needed for financial management, customer interaction, and formal employment may also be developed. Refugees in Nairobi are also less likely to engage in self-employment, raising a need to designate micro-enterprise-friendly zones in urban areas where refugee entrepreneurs can receive reduced rent, tax incentives, and logistical support, fostering a conducive environment for self-employment.

The decomposition results also suggest that informal financing has explanatory power over an individual’s choice to be self-employed. Respondents using formal financing were significantly fewer in the study sample, possibly because informal financing sources are generally more accessible to refugees than formal financial institutions, especially regarding collateral requirements, credit histories, or formal employment. The accessibility of informal financing lowers entry barriers for self-employment since informal lenders offer more flexible terms than formal lenders, making them appealing to individuals with irregular income streams. This flexibility can encourage individuals to pursue self-employment without the constraints imposed by banking requirements. Considering the lower interest and long-term advantage of formal finance, policies that facilitate documentation or work permits for refugees should be facilitated to allow refugees to engage more easily in economic activities. Policymakers can also design microfinance products with flexible repayment schedules and small loan sizes to cater to refugees’ irregular income patterns or loans that do not require collateral but are backed by social guarantees or group lending mechanisms, thus leveraging trust within refugee communities; this can be combined with small grants for first-time entrepreneurs to reduce risk and encourage business establishment.

From the findings, refugees with strong social capital/ties are less likely to embrace self-employment; this can be contextualized to suggest that refugees build networks that lead to wage employment after building ties with other members through the formation of associations. By promoting formalized savings groups, cooperatives, or community investment programs, policymakers can convert social networks into economic support systems, which might boost entrepreneurial activity without excessive reliance on social ties alone. Banks can also be mobilized to establish loaning systems that provide financing to refugee associations, which have informational advantages over refugee households, and, in turn, can loan to the refugees to undertake business. They can also partner with existing community savings and loan associations (CSLAs), ROSCAs, or diaspora financing groups to extend formal financing options. This partnership could involve providing training or matching funds to amplify the impact of these informal mechanisms.

This study also finds that men are more likely to take up financing than women. This unequal access to financial resources, social support, and entrepreneurial networks may cause a persistent gender gap in economic participation. We recommend creating affirmative policies encouraging women to access financing and embrace self-employment as an income-generating activity. Microfinance programs for women should be established or expanded, offering tailored financial literacy, mentoring, and capital access to bridge the gender gap. Policy advocates should also collaborate with local governments to create policies incentivizing financial institutions to serve refugee populations, such as tax breaks or subsidies.

Study Limitations and Areas of Further Research

This study focused exclusively on secondary data targeting the urban nationals and refugees in Nairobi, Nakuru, and Mombasa, registered with UNHCR. Due to the COVID-19 social distancing measures, the data were collected through computer-assisted telephone interviews; this may result in bias because some segments of the population may have been excluded, such as those without phone access, those unwilling to answer calls, or those not registered with the UNHCR. Because of this, the findings may not provide a comprehensive understanding of formal and informal financing mechanisms across different segments, contexts, and locations. Urban settings may present unique challenges and opportunities not representative of rural areas, where financial behaviors and access to resources can differ.

In addition, the study sample had very few respondents using formal financing, which restricts the ability to conduct robust comparative analyses between those who use formal mechanisms and those who rely on informal financing; this limits insights into the relative advantages, challenges, and outcomes of each financing pathway. As a result, the conclusions drawn from this research might be limited in scope. They may not be generalizable to all refugee or national populations, especially in regions or contexts where formal financing is more prevalent and where the dynamics of self-employment might differ significantly from those observed in this study.

Therefore, future research should incorporate data from urban and rural households to allow for a deeper exploration of the interplay between location and access to financial services, yielding more broadly applicable insights across different geographic and socioeconomic settings. In addition, more respondents should be included using formal financing, possibly through purposive sampling strategies targeting this group; this will provide a more holistic and nuanced analysis of the financing dynamics among refugees. There is also a need to focus on comparative studies to incorporate refugees from different cultural backgrounds or compare countries with inclusive versus restrictive financial policies for refugees in order to assess their effect on self-employment outcomes. For us to track the long-term impacts of financing choices on business growth, sustainability, and economic integration among refugees and nationals, a longitudinal study or panel data analysis should be conducted to determine these dynamics.