A Game-Theoretic Analysis of the Coexistence and Competition Between Hard and Fiat Money

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Hard Money

2.2. Cryptocurrencies and Central Bank Digital Currencies

2.3. Competition Between Fiat Currencies

2.4. Competition Between Cryptocurrencies and Fiat Currencies

2.5. Algorithmic Stablecoins and the Blurring of Monetary Boundaries

2.6. Inflation and Currencies

2.7. Transaction Cost and Currencies

2.8. Game-Theoretic Analyses

2.9. Summary and Connection to the Present Study

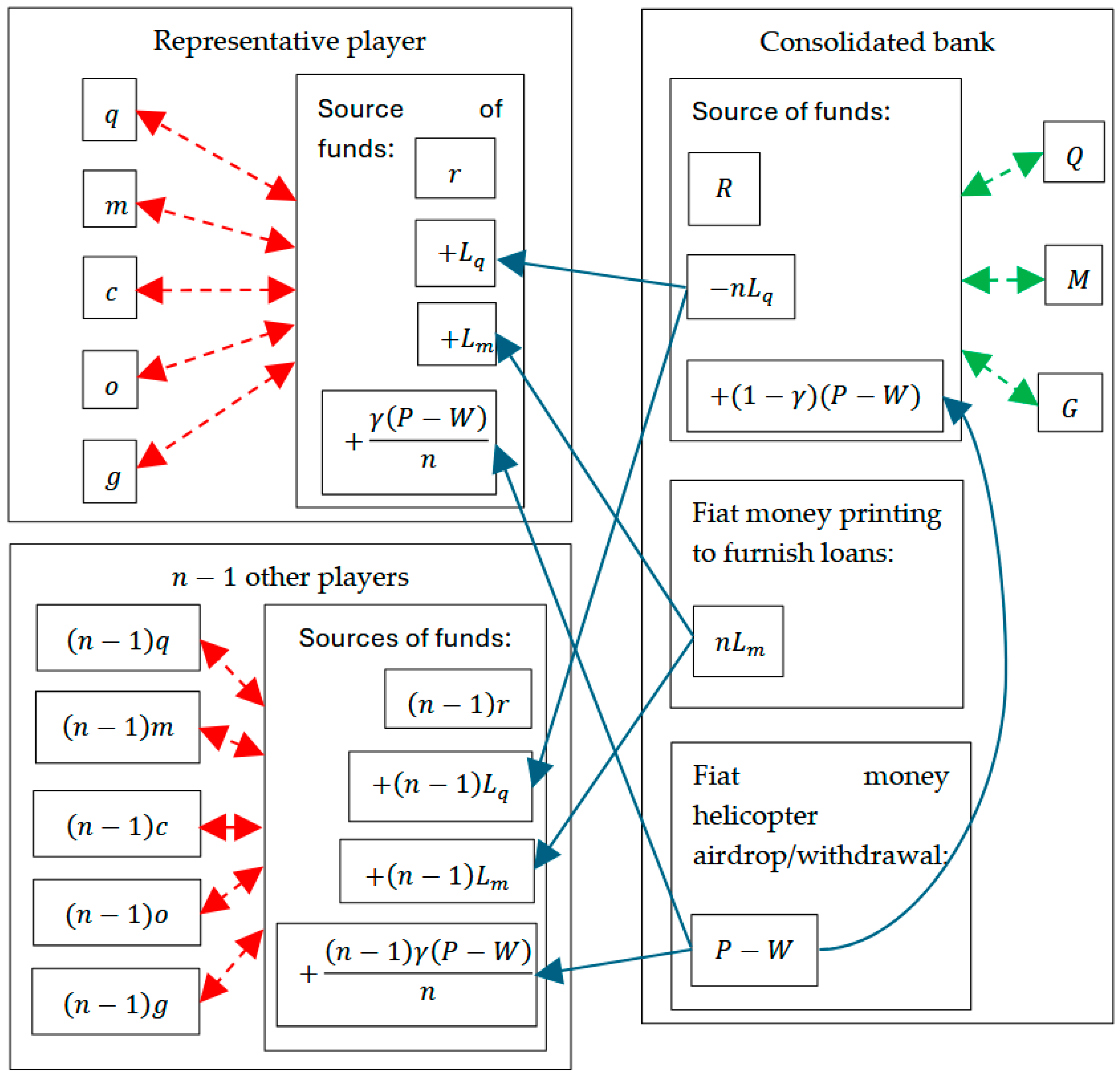

3. The Model

3.1. A Representative Player

3.2. The Bank

3.3. The Inflation Rate

4. Analyzing the Model

4.1. The Player’s Six Interior First-Order Conditions

4.2. The Bank’s Three Interior First-Order Conditions

5. Illustrating and Interpreting the Model

5.1. Benchmark Parameter Values and Model Setup

5.2. Economic Assumptions and Justifications

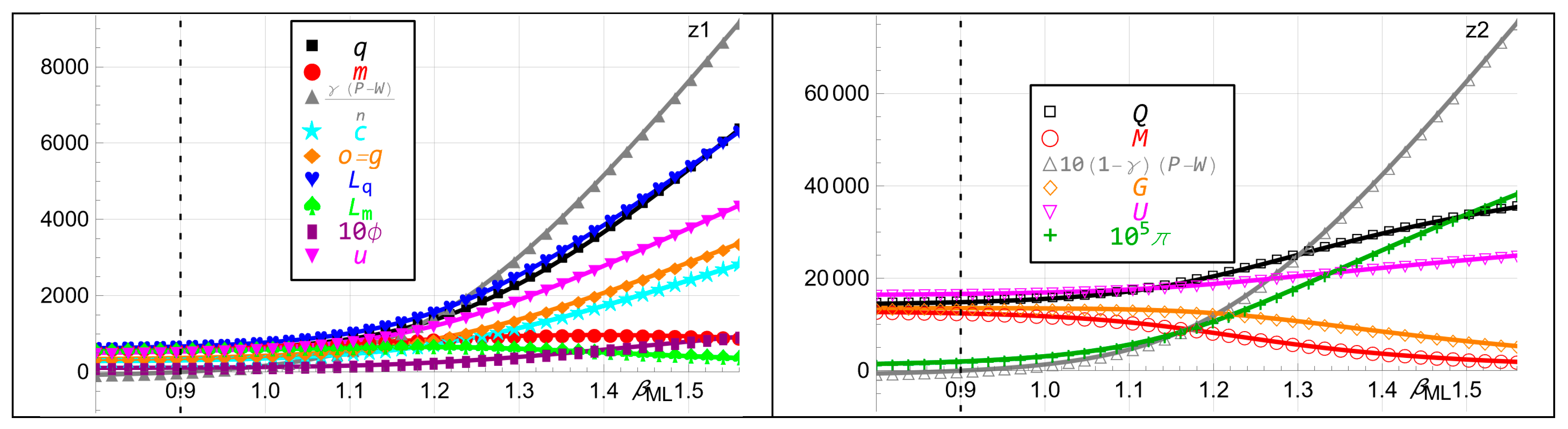

5.3. Interpretation of Figure 2 and Approach to Parameter Variations

5.4. Effects of Hard and Fiat Money Interest Rates on Inflation and Utility

5.5. Impact of the Number of Players on Inflation and Bank Lending

5.6. The Impact of Fiat Money Allocation on Inflation and Utility

5.7. The Role of Transaction Costs in Money Allocation and Inflation

5.8. Bank Preferences and Strategic Fiat Money Printing

5.9. Table Illustration

6. The Role of Prices in the Model

- Interest Rates: Higher hard money interest rates lead to increased holdings by the bank and decreased inflation, but paradoxically reduce the utility for the player by constraining its allocation towards hard money. Conversely, higher fiat money interest rates encourage money printing, increase inflation, and eventually diminish the coexistence of hard money, benefiting both the player and the bank in terms of utility.

- Utility Exponents: The utility exponents for both hard and fiat money for the player and the bank (their preferences for holding different types of money) determine how resources are allocated between these two forms of money. For instance, higher exponents for fiat money holding by the bank increase its allocation towards fiat money, impacting inflation rates.

- Transaction Costs: Transaction costs associated with using hard or fiat money significantly impact the player’s allocation preferences. Lower transaction costs for one form of money increase its attractiveness and holding levels, indirectly influencing market prices.

- Fiat Money Supply: The bank’s ability to print or withdraw fiat money directly influences inflation, which in turn affects the nominal values of goods, assets, and money in the economy. More fiat money printing generally increases inflation and nominal prices, whereas withdrawal reduces inflation.

- Inflation Rate: The inflation rate in (7) is a key determinant of the price level and is influenced by the amount of fiat money in circulation relative to hard money and the volume of loans.

- Player’s Strategic Allocation: The representative player allocates its resources across consumption, holdings (hard and fiat money, gold, and other assets), and loans. Changes in the player’s resource allocation impact its transaction costs and overall utility, indirectly determining the price it is willing to pay for goods and loans.

- Bank’s Strategic Behavior: The bank adjusts its holdings and lending strategies based on market conditions, fiat money availability, and inflation. Its actions, such as increasing fiat money lending or withdrawing funds, directly impact the prices by modifying the monetary base.

- Key Insights: Inflation and the relative utility derived from different forms of money play central roles in price determination. The strategic interactions between the representative player and the bank create mutually best response conditions where prices stabilize depending on the chosen parameter values.

7. Interpreting the Model

7.1. Most Essential Insights

- Increasing the hard money interest rate causes fiat money withdrawal and, paradoxically, lowers player utility and, eventually, bankruptcy by restraining the player’s allocation possibilities. The inflation decreases and eventually transitions to deflation. The bank’s allocation possibilities are also restrained, but it receives higher utility through increasing its hard money holding and decreasing its gold holding. Thus, a higher interest rate for hard money does not necessarily make it more attractive for the player but, rather, may benefit the bank at the player’s expense, as shown in Figure 2b.

- In contrast, increasing the fiat money interest rate causes fiat money printing, inflation, and higher utilities for the player and bank. The player first increases and thereafter decreases all its variables except its fiat money holding and utility. That causes hard and fiat money not to coexist. This highlights how fiat money policies can fundamentally alter the financial system, potentially making hard money obsolete, as shown in Figure 2c.

- More players mean more fiat money loans, which benefits the bank. That encourages the bank to withdraw fiat money and decrease its holdings of hard and fiat money and gold. The bank’s fiat money withdrawal causes lower utility for each player. As the inflation eventually decreases, each player increases its fiat money holding and fiat money borrowing and holds less hard money. This is crucial for central banks, as it suggests that an increasing number of borrowers does not necessarily benefit the broader economy, as shown in Figure 2a.

- Allocating more printed fiat money to the player causes inflation and induces the player to consume more, hold more hard money, borrow more hard money, and, eventually, hold less fiat money and borrow less fiat money. The inflation benefits the player since hard money is available in addition to fiat money. The bank is relatively unaffected. It benefits from the player’s increased borrowing but suffers from the increased allocation to the player. Allocating less printed fiat money to the player causes deflation. These results suggest that central banks should carefully monitor the impact of money printing to avoid destabilizing inflation, as shown in Figure 2s.

- Increasing the player’s hard money transaction cost parameter, and analogously for the fiat money transaction cost parameter, causes the player to consume more, hold more gold, hold less fiat money, borrow less, and earn higher utility. Hence, hard and fiat money can coexist with different transaction costs. The bank is relatively unaffected but prints fiat money and earns lower utility, which causes the player to first increase and then decrease its hard money holding. This shows that transaction costs play a critical role in determining which form of money dominates, not just inflation or interest rates, as shown in Figure 2p.

- Increasing the bank’s fiat money exponent causes fiat money printing and inflation. The bank earns higher utility by holding more fiat money, eventually less hard money, and substantially less gold. The player’s variables including its utility increase, except its fiat money holding and fiat money loan, which first increase and eventually decrease. This shows that banks may strategically use fiat money printing to their advantage, even if it comes at the cost of long-term stability, as shown in Figure 2w.

7.2. Essential Insights

- Increasing the player’s hard money borrowing interest rate induces the bank to withdraw fiat money. That causes the player to borrow more fiat money, which initially causes inflation, and also borrow more hard money because of the restrained allocation possibilities. That causes lower player utility and higher bank utility. Thus, higher hard money borrowing costs do not necessarily curb inflation but can instead fuel it, as shown in Figure 2f.

- Increasing the player’s fiat money borrowing interest rate also induces the bank to withdraw fiat money. That causes the player to borrow more hard money, and also borrow more fiat money because of the restrained allocation possibilities. That causes inflation, lower player utility, and higher bank utility. Thus, higher fiat money borrowing costs also do not necessarily curb inflation but can instead fuel it, as shown in Figure 2g.

- Increasing the bank’s hard money exponent in its utility causes fiat money withdrawal and decreased inflation. The bank earns higher utility by holding more hard money, slightly more fiat money, and substantially less gold. All the player’s variables including its utility decrease and eventually approach zero. This demonstrates the power banks have over inflation by strategically adjusting money supply and asset allocations, as shown in Figure 2v.

7.3. Insights

- Increasing the player’s hard money holding exponent in its utility, and analogously for the other exponents, causes the player to allocate more resources to hard money, less and, eventually, nothing to everything else, and earn higher utility. The inflation decreases because the bank’s fiat money printing is offset by the player’s decreased borrowing, which causes lower bank utility, as shown in Figure 2j.

- Increasing the player’s hard money loan exponent in its utility, and analogously for the other exponents, initially induces the player to borrow more hard money. That causes the bank to earn higher utility through withdrawing fiat money, which initially induces the player to also borrow fiat money, and earn lower utility, accompanied with inflation, as shown in Figure 2n.

- Increasing the bank’s fiat money loan exponent increases fiat money printing and inflation. The bank earns higher utility by holding more hard money and less fiat money and gold. The player earns higher utility by increasing all its variables except its fiat money holding and fiat money loan, which first increase and, eventually, decrease, as shown in Figure 2z.

8. Policy Implications for Central Banks

8.1. Inflation Control Through Strategic Money Printing and Withdrawal

- Central banks should moderate fiat money printing to avoid excessive inflation, which can drive out hard money from circulation.

- A balance between money supply expansion and contraction is necessary to prevent liquidity shortages that could harm borrowers and disrupt financial stability.

- Policy tools such as open market operations and interest rate adjustments should be dynamically utilized to counter inflationary and deflationary risks.

8.2. Interest Rate Adjustments

- Raising fiat money interest rates encourages fiat money printing and inflation, which may eliminate hard money from the financial system. Policymakers should manage this process carefully to avoid excessive inflationary pressure.

- Higher hard money interest rates paradoxically constrain liquidity for players, benefiting the bank at the player’s expense. Thus, setting appropriate interest rates requires a balance between incentivizing fiat money use and ensuring economic stability.

8.3. Managing Money Supply in Multi-Currency Economies

- In economies where hard and fiat money coexist, central banks must ensure monetary stability by adjusting the fiat supply based on inflationary trends.

- Targeted money withdrawal strategies can be employed to reduce inflationary pressures while maintaining a stable financial environment.

- Regulations surrounding the adoption of cryptocurrencies and hard money substitutes should be considered to prevent the destabilization of fiat currency systems.

8.4. Role of Transaction Costs in Currency Adoption

- Policies that lower transaction costs for digital fiat currencies (e.g., CBDCs) can increase fiat money adoption while limiting inflation risks.

- Higher transaction costs for hard money discourage its use, reinforcing fiat money dominance. Central banks should evaluate the impact of these costs on financial stability and economic efficiency.

- Incentivizing digital payment adoption and improving infrastructure for digital currencies can reduce reliance on physical cash, further stabilizing monetary policy implementations.

9. Broader Macroeconomic Implications

9.1. Impact on Global Trade and Exchange Rates

- Digital currencies can reduce exchange rate volatility by enabling faster and more stable cross-border transactions.

- CBDCs and stablecoins could facilitate international trade by lowering remittance costs and improving financial efficiency.

- Countries with well-established digital payment infrastructures may gain competitive advantages in global markets by reducing transaction delays and enhancing liquidity.

9.2. Shifts in Global Reserve Currencies

- The rise in CBDCs could decrease reliance on traditional reserve currencies, such as the U.S. dollar, leading to a more multipolar financial system.

- Digital currency adoption could shift the balance of financial power, allowing smaller economies to bypass conventional banking systems and access global liquidity directly.

- The ability of CBDCs to settle transactions instantly and securely could enhance monetary sovereignty for emerging markets, reducing their vulnerability to external shocks.

9.3. Effects on Capital Flows and Financial Stability

- Digital currencies could accelerate capital mobility, leading to increased financial volatility in economies with weak regulatory frameworks.

- Large-scale digital currency transactions could facilitate capital flight from unstable economies, making them more susceptible to external financial shocks.

- To mitigate these risks, central banks must establish robust financial stability measures, such as capital controls on digital asset transactions and international cooperation on regulatory standards.

9.4. Trade and Digital Payment Infrastructure

- Countries investing in blockchain-based trade settlements could enhance trade efficiency and financial inclusion, benefiting exporters and importers.

- Smart contract-based payment systems could automate trade agreements, reducing reliance on traditional banking intermediaries.

- The expansion of decentralized finance (DeFi) and programmable money could enable seamless cross-border commerce, changing the dynamics of international business and monetary policy.

10. Limitations and Future Research

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Nomenclature

| General parameters | |

| Number of players, | |

| Interest rate for asset determined by the open market, ; | |

| The players’ borrowing interest rate for hard money and fiat money ; | |

| Parameters for the player | |

| The representative player’s resources, | |

| The player’s utility exponent for consumption and holding asset ; | |

| The player’s utility exponent for loans in hard money and fiat money, | |

| The player’s transaction cost parameter for hard money and fiat money, | |

| The player’s scaling exponent for consumption , buying other assets and gold | |

| The fraction of fiat money helicopter airdrop/withdrawal allocated to the player, | |

| The scaling parameter of the player’s transaction cost, | |

| Parameters for the bank | |

| The bank’s resources, | |

| The bank’s utility exponent for holding asset | |

| The bank’s utility exponent for loan to the players, | |

| Player i’s free-choice variables | |

| Player ’s consumption and holding of assets, ; | |

| Player ’s hard money loan and fiat money loan ; | |

| The bank’s free-choice variables | |

| The bank’s holding of hard money and fiat money, ; | |

| The bank’s printing of fiat money minus the bank’s withdrawal of fiat money, ; | |

| Player i’s dependent variables | |

| The representative player’s utility, | |

| The player’s holding of gold, | |

| The bank’s dependent variables | |

| The bank’s utility, | |

| The bank’s holding of gold, | |

| The player’s and the bank’s dependent variables | |

| Inflation rate, | |

| The player’s transaction cost, | |

Appendix B. The Representative Player’s First-Order Conditions

Appendix C. The Bank’s First-Order Conditions

Appendix D. Interpretation of 14 of the Panels in Figure 2

| 1 | Examples are feathers, bones, seashells, cloth, grain, silver, gold, metal coins, paper money, banknotes, and electronic money. |

References

- Adrian, T., & Mancini-Griffoli, T. (2021). The rise of digital money. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 13, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, F., Argente, D., & Van Patten, D. (2022). Are cryptocurrencies currencies? Bitcoin as Legal Tender in El Salvador (Working Paper No. 29968). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Ammous, S. (2018). The Bitcoin Standard: The decentralized alternative to central banking. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ammous, S., & D’Andrea, F. A. M. C. (2022). Hard money and time preference: A Bitcoin perspective. MISES: Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy, Law and Economics, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos, S., Lorusso, M., & Ravazzolo, F. (2019). A new economic framework: A DSGE model with cryptocurrency (Working Paper. No.07/2019). Centre for Applied Macro- and Petroleum Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Ayadi, A., Ghabri, Y., & Guesmi, K. (2023). Directional predictability from central bank digital currency to cryptocurrencies and stablecoins. Research in International Business and Finance, 65, 101909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, C. T., Clegg, R. G., Steer, B. A., & Zignani, M. (2024). Investigating shocking events in the ethereum stablecoin ecosystem through temporal multilayer graph structure. arXiv, arXiv:2407.10614. [Google Scholar]

- Badev, A., & Watsky, C. (2023). Interconnected Defi: Ripple effects from the Terra collapse (Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2023-044). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [Google Scholar]

- Benchimol, J., & Fourçans, A. (2012). Money and risk in a Dsge framework: A bayesian application to the Eurozone. Journal of Macroeconomics, 34(1), 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigno, P., Schilling, L. M., & Uhlig, H. (2022). Cryptocurrencies, currency competition, and the impossible trinity. Journal of International Economics, 136, 103601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S. (2023). Money in the time of Crypto. Research in International Business and Finance, 65, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissay, F., Cornelli, G., Doerr, S., & Frost, J. (2022). Blockchain scalability and the fragmentation of Crypto (No. 56). Bank for International Settlements. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/bisbull56.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Bordo, M. D. (1983). Some aspects of the monetary economics of richard cantillon. Journal of Monetary Economics, 12(2), 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordo, M. D., Dittmar, R. D., & Gavin, W. T. (2007). Gold, fiat money, and price stability. The BE Journal of Macroeconomics, 7(1). Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.2202/1935-1690.1525/html (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Bordo, M. D., & Vegh, C. A. (2002). What if alexander hamilton had been Argentinean? A comparison of the early monetary experiences of Argentina and the United States. Journal of Monetary Economics, 49(3), 459–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briola, A., Vidal-Tomás, D., Wang, Y., & Aste, T. (2022). Anatomy of a Stablecoin’s failure: The Terra-Luna case. arXiv, arXiv:2207.13914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caginalp, C., & Caginalp, G. (2019). Establishing cryptocurrency equilibria through game theory. AIMS Mathematics, 4(3), 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Wu, J., Jeon, B. N., & Wang, R. (2017). Monetary policy and bank risk-taking: Evidence from emerging economies. Emerging Markets Review, 31, 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J., Davoodalhosseini, S. M., Jiang, J., & Zhu, Y. (2023). Bank market power and central bank digital currency: Theory and quantitative assessment. Journal of Political Economy, 131(5), 1213–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, A. C., & Lai, C. C. (2013). Money and the welfare cost of inflation in an R&D growth model. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 45(1), 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, L. W., & Mayer, S. (2022). The coming battle of digital currencies (The SC Johnson College of Business Applied Economics and Policy Working Paper Series, No. 2022-04). SC Johnson. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R. N., Dornbusch, R., & Hall, R. E. (1982). The gold Standard: Historical facts and future prospects. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1982(1), 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan Van, D. (2020). Money supply and inflation impact on economic growth. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 12(1), 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, P., & Geanakoplos, J. (2003). Inside and outside fiat money, gains to trade, and Is-Lm. Economic Theory, 21, 347–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineer, M. (2000). Currency transactions costs and competing fiat currencies. Journal of International Economics, 52(1), 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, R. C. (1986). Functional equivalence between liquidity costs and the utility of money. Journal of Monetary Economics, 17(2), 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feres, A. (2021). Fiat, debt, & inflation: Has the federal reserve financially enslaved our great nation? (28720363) [Doctoral dissertation, Utica College]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/8a827460ee3c936c14eeb17a276f1f00/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Fernández-Villaverde, J., & Sanches, D. (2019). Can currency competition work? Journal of Monetary Economics, 106, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Villaverde, J., & Sanches, D. (2023). A model of the gold Standard. Journal of Economic Theory, 214, 105759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari Minesso, M., Mehl, A., & Stracca, L. (2022). Central bank digital currency in an open economy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 127, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, S., & Furini, M. (2024). Cryptocurrency turmoil: Unraveling the collapse of a Unified Stablecoin (Ustc) through Twitter as a passive sensor. Sensors, 24(4), 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, I. (1911). The purchasing power of money: Its determination and relation to credit, interest, and crises. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, I. (1920). The Purchasing Power of Money: Its Determination and Relation to Credit, Interest and Crises (New and revised edition). Macmillan Company. Available online: https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/3610 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Forbes Advisor. (2024). Credit card processing fees: The ultimate guide. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/business/credit-card-processing-fees/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Fu, S., Wang, Q., Yu, J., & Chen, S. (2022). Rational ponzi games in Algorithmic stablecoin. arXiv, arXiv:2210.11928. [Google Scholar]

- Gertler, M., & Kiyotaki, N. (2015). Banking, liquidity, and bank runs in an infinite horizon economy. American Economic Review, 105(7), 2011–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, H. (1992). The non-neutrality of money and the optimal monetary growth rule when preferences are recursive: Cash-in-advance vs. money in the utility function. Journal of Macroeconomics, 14(2), 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itaya, J. I., & Mino, K. (2003). Inflation, transaction costs and indeterminacy in monetary economies with endogenous growth. Economica, 70(279), 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. (2023). Is Zimbabwe’s recently released gold-backed digital currency a good idea? Available online: https://internationalbanker.com/brokerage/is-zimbabwes-recently-released-gold-backed-digital-currency-a-good-idea/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Jumde, A., & Cho, B. Y. (2020). Can cryptocurrencies overtake the fiat money? International Journal of Business Performance Management, 21(1–2), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keister, T., & Sanches, D. (2023). Should central banks issue digital currency? The Review of Economic Studies, 90(1), 404–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. (2017). On the transaction cost of Bitcoin. Finance Research Letters, 23, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosse, A., & Mattei, I. (2023). Making headway—Results of the 2022 Bis survey on central bank digital currencies and crypto (Paper No. 136). Bank for International Settlements. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap136.htm (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Kwon, Y., Pongmala, K., Qin, K., Klages-Mundt, A., Jovanovic, P., Parlour, C., Gervais, A., & Song, D. (2023). What drives the (in)stability of a stablecoin? arXiv, arXiv:2307.11754. [Google Scholar]

- Laboure, M., H.-P. Müller, M., Heinz, G., Singh, S., & Köhling, S. (2021). Cryptocurrencies and Cbdc: The route ahead. Global Policy, 12(5), 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos, R., Rocheteau, G., & Wright, R. (2017). Liquidity: A new monetarist perspective. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(2), 371–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, B., Zhuang, L., & Zhou, Q. (2023). An evolutionary game analysis of digital currency innovation and regulatory coordination. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, 20(5), 9018–9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S., Pei, H., Tian, H., & Lang, K. (2021). Can both Bitcoin and gold serve as safe-haven assets?—A comparative analysis based on the Nardl model. International Review of Financial Analysis, 78, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoorian, A., & Michelis, L. (2005). Money, habits and growth. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 29(7), 1267–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A., & Schreft, S. L. (2006). Currency competition: A partial vindication of hayek. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53(8), 2085–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciandaro, D., & Volpicella, A. (2016). Macro prudential governance and central banks: Facts and drivers. Journal of International Money and Finance, 61, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, B. T. (1997). Crucial issues concerning central bank independence. Journal of Monetary Economics, 39(1), 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, A., Straub, L., & Sufi, A. (2021). A goldilocks theory of fiscal policy. NBER Working Paper, No.w29351. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, B., & Prasad, E. S. (2024). A simple model of a central bank digital currency. Journal of Financial Stability, 73, 101282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabilou, H. (2020). Testing the waters of the rubicon: The European central bank and central bank digital currencies. Journal of Banking Regulation, 21(4), 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Nicholson, J. S. (1888). A treatise on money and essays on present monetary problems. William Blackwood and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Nyathi, L. D., & Mutale, J. (2025). Perceptions of the Zimbabwe Gold Currency (Zig) as a Panacea to economic stability. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 9(15), 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E. Y., & Zhang, S. (2022). Informal economy and central bank digital currency. Economic Inquiry, 60(4), 1520–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocheteau, G., & Nosal, E. (2017). Money, payments, and liquidity. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rolnick, A. J., & Weber, W. E. (1997). Money, inflation, and output under fiat and commodity standards. Journal of Political Economy, 105(6), 1308–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, Y., & Kurosaki, T. (2023). Have cryptocurrencies become an inflation hedge after the reopening of the U.S. economy? Research in International Business and Finance, 65, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygılı, H. (2012). Consumption (in) Efficiency and financial account management. Bulletin of Economic Research, 64(3), 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharnowski, S. (2022). Central bank speeches and digital currency competition. Finance Research Letters, 49, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, L. M., & Uhlig, H. (2019). Currency substitution under transaction costs. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt-Grohé, S., & Uribe, M. (2004). Optimal fiscal and monetary policy under sticky prices. Journal of Economic Theory, 114(2), 198–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, P., & Sigmund, K. (1983). Replicator dynamics. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 100(3), 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senner, R., & Sornette, D. (2019). The holy grail of crypto currencies: Ready to replace fiat money? Journal of Economic Issues, 53(4), 966–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, W. H. (1941). Money and banking. H. Holt and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, J. (1998). How high can inflation get during hyperinflation? A transaction cost demand for money approach. European Journal of Political Economy, 14(3), 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Hausken, K. (2021a). Conventionalists, pioneers and criminals choosing between a national currency and a global currency. Journal of Banking and Financial Economics, 2(16), 104–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Hausken, K. (2021b). Governmental taxation of households choosing between a national currency and a cryptocurrency. Games, 12(2), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Hausken, K. (2022a). Competition between variable–supply and fixed–supply currencies. Economies, 10(11), 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Hausken, K. (2022b). The evolution of fixed-supply and variable-supply currencies. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Hausken, K. (2022c). A game between central banks and households involving central bank digital currencies, other digital currencies and negative interest rates. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2114178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., & Hausken, K. (2024). Hard money and fiat money in an inflationary world. Research in International Business and Finance, 67, 102115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wei, Y., Lucey, B. M., & Su, Y. (2023). Return spillover analysis across central bank digital currency attention and cryptocurrency markets. Research in International Business and Finance, 64, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welburn, J. W., & Hausken, K. (2017). Game theoretic modeling of economic systems and the european debt crisis. Computational Economics, 49(2), 177–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F., Tong, X., & Ren, X. (2022). Gold or bitcoin, which is the safe haven during the COVID-19 pandemic? International Review of Financial Analysis, 81, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Gold Council. (2024). Gold production by country 2024–Report. Available online: https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/gold-production-by-country (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Yu, Z. (2023). On the coexistence of cryptocurrency and fiat money. Review of Economic Dynamics, 49, 147–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. (2000). Inflation and growth: Pecuniary transactions costs and qualitative equivalence. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Figure 2 | The Player’s Variables | The Bank’s Variables | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | |||||||||||||||||

| b | |||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||

| d | |||||||||||||||||

| e | |||||||||||||||||

| f | |||||||||||||||||

| g | |||||||||||||||||

| h | |||||||||||||||||

| i | |||||||||||||||||

| j | |||||||||||||||||

| k | |||||||||||||||||

| l | |||||||||||||||||

| m | |||||||||||||||||

| n | |||||||||||||||||

| o | |||||||||||||||||

| p | |||||||||||||||||

| q | |||||||||||||||||

| r | |||||||||||||||||

| s | |||||||||||||||||

| t | |||||||||||||||||

| u | |||||||||||||||||

| v | |||||||||||||||||

| w | |||||||||||||||||

| x | |||||||||||||||||

| y | |||||||||||||||||

| z | |||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hausken, K.; Wang, G. A Game-Theoretic Analysis of the Coexistence and Competition Between Hard and Fiat Money. Economies 2025, 13, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030080

Hausken K, Wang G. A Game-Theoretic Analysis of the Coexistence and Competition Between Hard and Fiat Money. Economies. 2025; 13(3):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030080

Chicago/Turabian StyleHausken, Kjell, and Guizhou Wang. 2025. "A Game-Theoretic Analysis of the Coexistence and Competition Between Hard and Fiat Money" Economies 13, no. 3: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030080

APA StyleHausken, K., & Wang, G. (2025). A Game-Theoretic Analysis of the Coexistence and Competition Between Hard and Fiat Money. Economies, 13(3), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030080