Abstract

As countries worldwide endeavor to fulfill the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10, which emphasizes reducing inequality, there is a growing imperative to utilize tax policy and institutions to accomplish this objective. Hence, this study is inspired by this rationale. The aim of this study is to assess the relationship between effective VAT (calculated as total VAT revenues divided by final consumption, which reflects the economic incidence of the tax rather than its legal definition), institution index, and income inequality. To achieve this objective, this study uses the system generalized method of moments (SGMM) for 35 Sub Saharan Africa countries from 1995 to 2021. The results show that effective VAT increases income inequality in both the short and long run. However, the effect of the long run is greater than that of the short run. Furthermore, the results reveal that institutional quality reinforced the positive effect of effective value added tax on income inequality in both the short and long run, with the long run being more pronounced than the short run. This suggests that effective VAT policies and institutional quality applied in this study augment income inequality. Additionally, it is also noticed that ethnic fragmentation impedes effective VAT to lower income disparity in the short and long run in SSA. Hence, a relevant policy to strengthen the tax system and improve institutional quality should be given priority in SSA.

JEL Classification:

H20; O11; O15

1. Introduction

Policymakers and researchers are increasingly concerned about the rapid rise of global inequality and its substantial effects on macroeconomic stability and growth. The increasing number of poor people worldwide has prompted calls for more equitable resource distribution (Aremo & Abiodun, 2020). This growing income inequality underscores the importance of fiscal policy in narrowing the income gap between lower and higher-income individuals (Fernandes et al., 2019). Fiscal policy, through taxation and public spending, can directly affect income gaps via monetary payments or indirectly by providing free services like education and healthcare, thereby enhancing institutional quality. In Africa, economic growth is expected to improve living standards (Rodrik, 2014). However, this requires significant investment in education, healthcare, and public utilities, which many SSA governments cannot afford due to tight budgets. The tax ratio in most African countries is 15% or lower, insufficient for funding economic and human development. While international financial aid could support public investment, it is limited due to recessions in wealthy countries, highlighting the need for better local tax revenue collection to improve institutional quality and reduce inequality.

The VAT is one of the most significant developments in tax systems since the introduction of personal income tax in both developing and developed economies. It accounts for a large portion of tax revenue in many developing nations and plays a crucial role in promoting tax transition (Adandohoin, 2021). Advantages of VAT include preventing the cascading of indirect taxes, being harder to evade, and ease of implementation for international trade. VAT is also considered a “Money Machine” for generating more revenue (Keen & Lockwood, 2010). However, its appropriateness for developing economies is debated. Emran and Stiglitz (2005) argue that VAT can be problematic in economies with large informal sectors, while Keen (2008) contends that VAT indirectly taxes the informal sector by being levied on inputs and imports. Some scholars, including Gemmell and Morrissey (2005) and Bird and Zolt (2005), suggest that the border taxes replaced by VAT may have been less regressive. The regressivity of indirect taxes like VAT is considered a factor in the rising income gap in many countries, as they disproportionately affect lower-income individuals who pay a larger portion of their income on these taxes (Kozuharov et al., 2015). Indirect taxes impact everyone regardless of income, often widening the income gap further, especially for those with lower incomes who spend a larger percentage of their income on VAT.

The seminal work of Meltzer and Richard (1981) shows that democratization, by enlarging political power to poor households, will augment the tendency for pro-poor policy, naturally linked with redistribution and hence lower income disparity. This is consistent with Acemoglu et al. (2013), who use OLS and GMM and found that the effect of fiscal redistribution on inequality depends on the democracy channel. Recently, Messy and Ndjokou (2021) assessed which tax variable among tax structures (direct or indirect taxes) and the weight of tax revenue lower inequality in SSA using Fixed Effect Ordinary Least Squares. By interacting with tax revenue and corruption, their results reveal that tax revenue significantly lowers inequality in an economy with a low level of corruption.

Contrary to the above authors, this study examines the combined effect of EVAT and institution quality on income inequality in SSA. for several reasons: (i) We use EVAT as one of the main tax instruments contributor to the total tax revenue in SSA though the total tax revenue in SSA is lower than others regions. (ii) The SSA region is characterized by a higher level of income inequality and weak institutions compared to other regions. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) faces significant challenges with income inequality, as evidenced by its high Gini coefficients, with six of the ten most unequal countries globally located in the region (World Inequality Database, 2023). Despite the potential of VAT as a tool for generating government revenue, SSA struggles with low tax compliance, particularly in the informal sector, which exacerbates inequality. Recent data shows that the richest 10% control a disproportionate share of income, contributing to persistent inequality (African Development Bank, 2010). The effectiveness of VAT in SSA is further hindered by high levels of informality and weak enforcement, which limits its redistributive potential. Moreover, compared to other regions like Latin America, SSA’s tax system has made limited progress in reducing inequality, suggesting the need for more targeted reforms in taxation and public expenditure to address these structural issues (World Bank, 2020). The institutional quality index, which includes control of corruption, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and voice and accountability, is crucial for the successful implementation and impact of VAT policies. Robust institutions can enhance tax compliance, reduce corruption, and ensure efficient public resource allocation, thereby decreasing income inequality (Kaufmann et al., 2009). Conversely, weak institutions can lead to tax evasion, corruption, and inefficient public spending, exacerbating economic disparities (Gupta et al., 2002). Therefore, understanding the relationship between effective VAT implementation and high institutional quality is essential for designing policies that encourage inclusive growth and economic equity in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The Equity-Efficiency Trade-off Theory suggests a balance between economic efficiency and equity, with VAT being efficient due to its broad tax base and low evasion rates, yet potentially regressive by disproportionately impacting lower-income households. Institutional quality plays a vital role in managing this trade-off; high-quality institutions can design complementary policies, like targeted transfers or progressive subsidies, to mitigate VAT’s regressive effects and enhance equity (Tanzi & Zee, 2000). Acemoglu’s research underscores the importance of institutions, defined as the rules and norms governing economic, political, and social interactions, as fundamental to economic performance and income distribution. He differentiates between Inclusive Institutions, which promote economic participation, enforce property rights, and provide public goods equitably, thus supporting economic growth and equitable resource distribution (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012), and extractive institutions, which concentrate power and wealth among a few, restrict economic opportunities for the majority and are often marked by corruption and weak rule of law, leading to economic stagnation and high-income inequality. In this context, financial development plays a crucial role in shaping income inequality. As financial systems expand, they can either reduce inequality by broadening access to financial services or increase disparities by favoring wealthier individuals, as emphasized by Chletsos and Sintos (2023) and De Haan and Sturm (2017). Additionally, institutional quality significantly influences inequality, as strong institutions can promote equitable economic growth, while weak institutions may reinforce existing disparities (North, 1990).

Therefore, this study empirically investigates the effect of EVAT and institution quality on income inequality from 1995 to 2021. In so doing, our paper answers two questions: (i) Does VAT impact income inequality, if yes, is the impact similar in the short and long run? (ii) Is the impact of VAT on income inequality conditional on institution quality? In answering the above questions, we contribute by expanding the literature on VAT and income inequality in various ways: (i) While most scholars assess VAT (focusing on its legal definition)–income inequality nexus and the institution quality-income inequality association, this study empirically contributes to the previous studies by examining the joint impact of effective VAT (calculated as total VAT revenues divided by final consumption, which reflects the economic incidence of the tax rather than its legal definition) and institution quality on income inequality in both short and long run in SSA. Thus, the results from this study are expected to be robust and consistent given that it will help the policymakers in the reallocation of resources and may produce significant policy recommendations. (ii) We employ the Two-Step SGMM estimation method, integrating forward orthogonal deviations, setting it apart from the traditional SGMM approach that does not account for these deviations (Roodman, 2009). This improves the reliability and efficiency of parameter estimates, especially in the presence of small samples, missing data, and potential endogeneity issues. This makes it a robust choice for dynamic panel data analysis. (iii) Research indicates ethnic fragmentation affects income disparity (Chadha & Nandwani, 2018). Furthermore, Cogneau and Dupraz (2015) assert that understanding the development disparities in SSA requires an examination of their cultural and social specificities. Hence, it is important to assess the effect of effective VAT on income disparity focusing on ethnic fragmentation. It is noted that the effects of variables like gender and ethnic fragmentation cannot be directly estimated because these variables remain constant over time. To address this, this study utilizes the time-invariant regressors developed by Kripfganz and Schwarz (2019) in dynamic panel data analysis, specifically adapted to assess “time-invariant” variables such as ethnic fragmentation. Traditional estimation methods fall short due to their inability to accurately capture the true effects of “time-invariant” variables, the bias arising from the correlation between explanatory variables and unit effects in random-effects models, and the challenge of separating the effects of observed heterogeneity from time-invariant unit heterogeneity in fixed-effects models. However, these challenges are effectively addressed by employing the regressors of Kripfganz and Schwarz, which are tailored to evaluate “time-invariant” variables.

2. Motivation and Literature Review

Income disparity remains a significant issue in SSA, impeding economic development and social stability. Understanding how VAT and institutional quality together influence income inequality is essential for crafting effective policy interventions. This literature review synthesizes existing research on VAT, institutional quality, and income inequality, highlighting their interactions and identifying gaps in current knowledge. Musgrave (1959) emphasized that taxation is crucial for income redistribution, public goods provision, and government accountability. Although reducing reliance on natural resources and foreign aid is desirable, most SSA countries face challenges with resource mobilization. Tax mobilization in Africa is low compared to other regions, with SSA economies collecting only 14% of GDP in taxes in 2018 (UNU-WIDER, 2021). VAT, which accounts for about 40% of total tax revenue in African countries (Kagan, 2019), offers fewer evasion opportunities as buyers aim to maximize payments and sellers minimize receipts (Slemrod & Velayudhan, 2022). VAT is based on consumption rather than income, applying the same rate to all purchases (Kagan, 2019).

Also, The structure and efficiency of the redistribution system are crucial in analyzing the impact of VAT on income inequality. While VAT is generally regressive, its structure can vary significantly based on the goods and services taxed, the rates applied, and who bears the burden.

Structure of VAT:

- Goods and Services Taxed: VAT can be applied to a wide range of goods, but some essentials like food, healthcare, and education may be exempt or taxed at lower rates to reduce the regressive impact. Luxury goods may be taxed at higher rates, shifting the burden away from lower-income groups.

- Rates: Standard and differential VAT rates affect who bears the tax burden. A single uniform rate burdens lower-income households more, as they spend a larger share of their income on taxed goods.

- Who is Affected: In economies with a large gray economy, VAT enforcement is weak. Wealthy individuals and corporations may evade taxes, while poorer consumers who rely on informal markets bear the brunt, limiting the effectiveness of VAT as a redistributive tool.

Efficiency of Redistribution: The efficiency of the redistribution system depends on how VAT revenues are used. If allocated to public services like healthcare and education, VAT can mitigate its regressive nature. However, if public funds are mismanaged or if the tax system is not progressive, the impact on reducing inequality remains limited.

2.1. VAT and Income Inequality

VAT is a widely implemented consumption tax that significantly boosts government revenue in many SSA countries. However, its impact on income inequality is contentious. Critics claim VAT is regressive because lower-income households spend a larger portion of their income on consumption, thus bearing a higher relative tax burden (Bird & Gendron, 2007). This regressive effect can exacerbate income inequality if not offset by complementary policies. On the other hand, VAT’s efficiency in generating revenue can provide substantial funds for public services and redistributive programs. When effectively managed, these revenues can support social safety nets, healthcare, and education, which can help reduce income inequality (IMF, 2015). Therefore, the overall impact of VAT on inequality largely hinges on how the generated revenue is managed and redistributed.

2.2. Institutional Quality and Income Inequality

Institutional quality, which includes governance, legal integrity, and bureaucratic efficiency, is essential in shaping economic outcomes like income distribution. High-quality institutions are associated with better economic performance and a fairer distribution of resources (Kaufmann et al., 2009). These institutions ensure effective tax collection, reduce corruption and ensure that tax revenues are used efficiently for public goods and services that benefit the broader population (Gupta et al., 2002). On the other hand, weak institutions characterized by corruption, inefficiency, and poor governance can undermine the benefits of tax policies like VAT. In such settings, tax revenues may be misappropriated, decreasing the funds available for redistributive programs and worsening income inequality (Acemoglu et al., 2001). Chletsos and Sintos (2023) argue that financial development can reduce inequality by providing greater access to credit and investment opportunities, especially for marginalized groups. Conversely, De Haan and Sturm (2017) suggest that in developing economies, the financial sector may exacerbate inequality if its growth primarily benefits the affluent, limiting its broader impact. Furthermore, the role of institutional quality is vital, as effective institutions can ensure that financial development leads to more inclusive economic outcomes, while poor institutions may allow the benefits of financial growth to be unevenly distributed (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012).

2.3. Combined Effects of VAT and Institutional Quality

The interaction between Value-Added Tax (VAT) and the quality of institutions is crucial in determining their combined effect on income inequality. High-quality institutions can enhance the efficacy of VAT by ensuring tax compliance, reducing evasion, and directing revenues towards fair and inclusive development initiatives (Moore, 2007). Furthermore, effective institutions can implement additional measures such as progressive income taxes or targeted subsidies to alleviate VAT’s regressive impact and protect lower-income households (Tanzi & Zee, 2000). However, in environments with weak institutions, even well-designed VAT systems may struggle to reduce inequality due to inadequate enforcement, widespread evasion, and improper resource allocation. Corruption and inefficiency can divert VAT revenues away from public services, diminishing their potential to redistribute wealth and potentially exacerbating income gaps (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2008). Padhan et al. (2022) utilized the nonlinear autoregressive distributive lag model (ARDL) to analyze the influence of tax rates and government spending on income inequality. Their findings suggest that higher tax rates promote income equality, while government expenditure diminishes inequality. Malla and Pathranarakul (2022) investigated the impact of institutional capacity on fiscal policy’s effect on income distribution using the system GMM with data spanning from 2000 to 2019. Their results indicate that targeted fiscal spending on health and education reduces inequality in developed nations. Additionally, although the relationship between institutional capacity and fiscal policy aligns with expectations, these correlations are not statistically significant.

Empirical studies carried out in SSA highlight the pivotal role of institutional quality in shaping the impact of VAT on income inequality. For example, Keen and Lockwood (2010) observed significant disparities in both the revenue-generating efficiency of VAT and its effects on inequality across countries, depending on the strength of their institutional frameworks. Nations with more robust institutions were better equipped to utilize VAT revenues effectively for funding social programs, thereby alleviating inequality. Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) present historical and cross-country evidence demonstrating that inclusive institutions, which promote widespread economic participation and fair resource allocation, are crucial for diminishing income inequality. Their research indicates that in SSA, where institutional quality tends to be weaker, enhancing governance and combating corruption are vital steps for enhancing the effectiveness of VAT and other tax policies in tackling inequality. Alemayehu (2010) conducted a gendered fiscal incidence analysis in Ethiopia, revealing that VAT exacerbates the income gap regardless of gender, albeit with a more pronounced unequalizing effect on men. This discrepancy may be attributed to men’s higher consumption of heavily taxed items such as tobacco and alcohol. Bird and Zolt (2005) underscored the regressive characteristics of VAT, which disproportionately burden lower-income households, often encompassing marginalized ethnic groups. Alesina and Ferrara (2005) highlighted the considerable ethnic diversity within Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with an ethnic fragmentation index of approximately 65%, and over 70% of SSA nations exhibiting ethnically diverse populations. This ethnic heterogeneity is frequently linked to heightened levels of mismanagement and corruption, as observed by Mauro (1995), thereby undermining the efficacy of VAT and perpetuating income inequality. The collective findings suggest that although VAT serves as an efficient revenue-generating mechanism, its regressive nature and the socio-economic landscape in SSA necessitate meticulous policy formulation to alleviate its impact on income inequality.

This research suggests that institutional quality mitigates the favorable impact of VAT on inequality. Specifically, when a country generates substantial tax revenue from a specific fiscal tool such as VAT, institutional quality becomes crucial in addressing inequality. The collective influence of VAT and institutional quality on income inequality in SSA highlights the need for a comprehensive policy framework that addresses both taxation and institutional quality. While VAT is indispensable for revenue generation, its regressive nature requires careful management to prevent widening income gaps. Simultaneously, investments in institutional quality are imperative for diminishing inequality and fostering sustainable economic growth. Policymakers in SSA must integrate tax policies with strategies to enhance institutional quality, thus achieving a more equitable income distribution and promoting long-term economic stability.

3. Econometric Model and Data

3.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

This paper uses PCA to create a composite index for institutional quality (INST). To clarify the methodology, a brief explanation of PCA is necessary. PCA, first introduced by Karl Pearson in 1901 and further developed by Hotelling in 1933, is a method used to extract information from high-dimensional datasets. It transforms the data into new indices that encapsulate relevant information across distinct, uncorrelated dimensions. This technique reduces the number of variables while retaining as much original data as possible. In constructing the composite index for institutional quality (INST) variables, we utilized the first eigenvectors (loading matrix) from the PCA as the necessary weights, producing the following linear combination:

where: are the eigenvectors (weights) from the PCA and CC, PS_AV, GE, , RL and V_A are the six synthetics of the institutional quality index.

3.2. A Dynamic Panel Data Model

To analyze the association between VAT, institutional quality, and inequality; first, we use the Dumitrecu and Hurlin causality test to check the directional causality of the variables of interest, and second, system GMM (Blundell & Bond, 1998) is applied to account for omitted variables, measurement error, and endogeneity.

The models are specified as follows:

Model 1-6 excludes the interaction between EVAT and other regressors or control variables:

SGMM 7 includes the interaction between EVAT and institutional quality:

SGMM 8 incorporates the interaction between EVAT and ethnic fragmentation. We include ethnic fragmentation and its interaction with EVAT to check if these variables contribute to the relationship between EVAT and higher and persistent inequality in SSA:

where is income inequality, is the dynamic characteristic of the equation, is effective value added tax in GDP (the logarithm of real per capita GDP; INST represents institutional quality and GDPpc denotes GDP per capita, X represents the vector of control variables such as GDPpc is GDP per capita, VAT, inflation, corruption, gender equality (GEN), ethnic fragmentation (ETH), educational inequality (EDINEQ). describes the interaction term of EVAT with institutional quality. This shows that the impacts of VAT on inequality are conditional on institutional quality. are country-specific effect and time-specific effect, respectively. is the error term and is a vector estimated coefficients. The selected variables in the model are crucial for analyzing the relationship between VAT, institutional quality, and income inequality. Here’s a summary of their importance:

- The Gini coefficient: The Gini coefficient remains a standard measure of income inequality, capturing disparities in income distribution across society. It is critical for understanding income inequality dynamics (OECD, 2021).

- Lagged Income Inequality: The inclusion of lagged income inequality accounts for the persistence of inequality over time. Previous income inequality tends to shape current inequality, as social and economic structures can lock in patterns of inequality (Lustig, 2020; & Milanovic, 2016).

- Effective VAT in GDP: The effective VAT in GDP plays a direct role in public revenue generation, and the effectiveness of VAT can influence a country’s ability to redistribute income (Baldwin, 2020). Efficient VAT enforcement supports a government’s redistributive capacity, directly impacting income inequality.

- Institutional Quality (INST): Strong institutions are essential for effective governance, ensuring tax compliance and equitable redistributive policies. Recent studies highlight that institutional quality, including government efficiency and the rule of law, is a key determinant of income inequality (Kaufmann et al., 2020; Acemoglu & Robinson, 2019).

- GDP per Capita (GDPpc): Economic development, represented by GDP per capita, is a crucial determinant of income inequality. Higher GDP per capita is typically associated with greater resources for social redistribution, reducing income inequality (Chancel et al., 2021; Bourguignon, 2020).

- Control Variables: Additional factors like VAT design, inflation, corruption, gender equality, ethnic fragmentation, and educational inequality affect both the effectiveness of redistributive policies and income inequality. Recent research emphasizes that inflation erodes real income for poorer households (IMF, 2021), while corruption undermines tax systems (Jin & Lim, 2020). Educational inequality remains a key factor in persistent income inequality (OECD, 2020), and ethnic fragmentation can exacerbate inequality by reducing social cohesion (Alesina et al., 2020).

In this section, a panel dataset of 35 countries1 from 1995 to 2021 is assessed to examine the impact of VAT on income disparity. We take 3-year averages for all time-variable in order to diminish short-term fluctuations because of business cycles.2 Additionally, our key variables of interest, such as inequality, VAT, and GDP per capita vary slowly over time. The following model is estimated in this study using Blundell and Bond’s (1998) methodology: Since aggregate variables like inequality have considerable time persistence, we have included lagged inequality as an explanatory variable in Equations (2) and (3). In fact, the serial correlation of income inequality over the years is well established (Kurosaki, 2011). This allows us to examine dynamic panel data.3 To compute a long-run impact of an increase in EVAT on the income gap, this study follows Wooldridge (2013, p. 635)4 Note that the following challenges need to be handled in order to estimate Equation (3). (i) the lag regressand, incorporated as a regressor, is endogenous. (ii) As previously argued, omitted variable bias, reverse causality, and measurement errors make it difficult to examine the impacts of EVAT, institutional quality, and inequality. We employ system GMM to address the aforementioned issues even though we take advantage of the fact that the individual dimension in our panel data is bigger than the time dimension.

Regarding measurement errors, it is well known that the variables taxation and inequality are correlated with measurement errors. The lack of a consensus measure for these variables in the literature serves as evidence for this. Some key variables may be left out of the model in terms of omitted variables. Despite the fact that a number of determinants of income inequality are important, these variables are not included because they may be associated with other factors in the model. Finally, the reverse causality issue may be demonstrated by the fact that, although VAT influences inequality, reverse causation is also possible due to the fact that an increased VAT can lead to a higher level of income inequality. The inclusion of the lagged variable of income disparity in the model, however, makes it even more crucial to take into account its memory impact because income inequality is a path-dependent process that depends on its prior development (Teng, 2019). Due to all of the aforementioned factors, SGMM is the estimation method that best fits our study. The system GMM estimator is preferable because, as was said earlier, our regressand is time persistent. Additionally, using a suitable endogenous variable (EVAT) as a reliable instrument can address the potential endogeneity of our variables. The moderating effect of ethnic fragmentation on the relationship between EVAT and income disparity is examined using the dynamic panel estimator for time-invariant variables by Kripfganz and Schwarz (2019). This method is particularly suitable because it provides robustness against specification errors arising from the exogeneity assumption. Additionally, it allows for capturing the true effect of time-invariant variables, which is typically overlooked by other methods. A significant advantage of the two-step approach is that it enables the correction of estimates derived from traditional methods, which often rely on poorly specified assumptions about time-invariant regressors that do not impact the findings of time-series estimation.

3.3. Data Description

Table 1 provides the source et description of the variables.

Table 1.

Source and definition of the variables.

4. Results

4.1. Principal Component Analysis

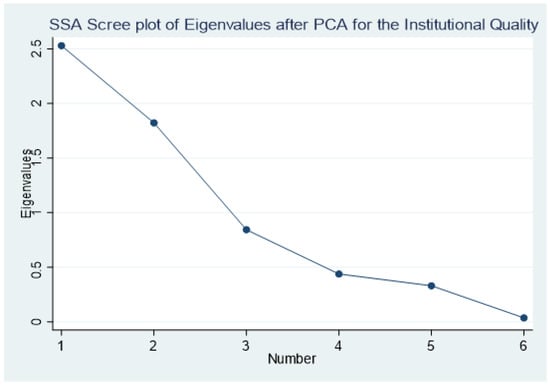

Table 2 presents the results of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and correlation matrix for the institutional quality (INST) variable in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). We started by examining the correlation between the indicators used to create the INST index. Panel A shows that the indicators are highly correlated, which supports the use of PCA for further estimation (Saba et al., 2024). To construct the composite index for institutional quality, we selected the first principal component, as it explains the highest percentage of total variation. Specifically, we chose the first component because its eigenvalue accounts for 2.35% of the total variation. The scree plots in Figure 1 further reinforce this choice. We used PCA to construct the institutional quality index from the following variables: control of corruption, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and voice and Accountability.

Table 2.

Principal Component Analysis and Correlation Matrix Results.

Figure 1.

Scree plot for Eigenvalue for INST.

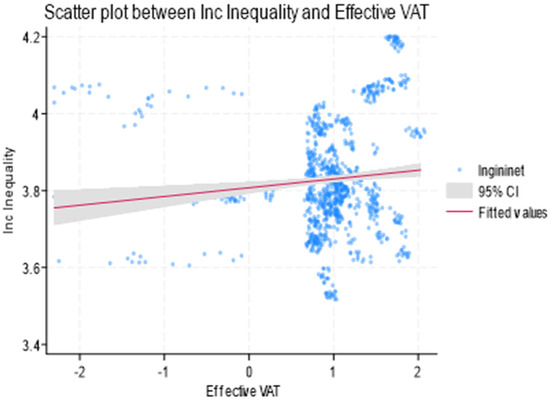

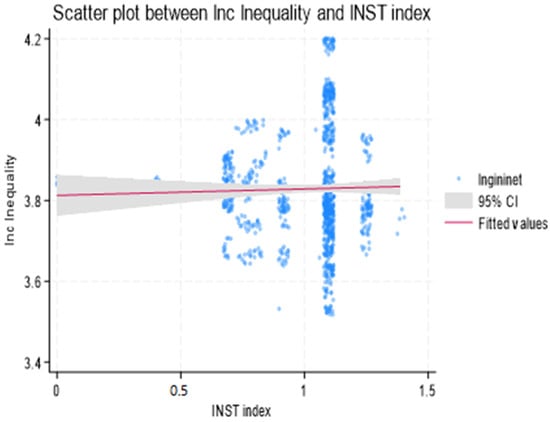

Before estimating the association between EVAT, institutional quality, and inequality, we look at the descriptive statistics, Table 3 presents the summary statistics while Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the correlation between variables. Figure 2 reveals a positive correlation while that of Figure 3 shows a slight negative correlation. Even though Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the correlation between our variables, they do not give directional causality. To observe the directional causality, we perform a panel causality between our variables. The results reveal that a bidirectional causality between EVAT and inequality while unidirectional causality running from institution to inequality has been observed in SSA.5 For the three primary variables we considered (see, Table 3), income inequality, EVAT, and institution, the mean values are 56.4, 3.04, and −0.002 respectively. The Gini variable records the highest mean while the institution records the smallest mean value.

Table 3.

Summary Statistics.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot between inequality and EVAT.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot between inequality and INST index.

4.2. Effective VAT

Effective VAT (EVAT) is a measure used to assess the efficiency and impact of VAT collection relative to consumption within an economy. It is computed as the ratio of total VAT revenues to final consumption. This variable is constructed as follows:

- Total VAT Revenues: This refers to the total amount of VAT collected by the government from the consumption of goods and services. VAT is a consumption-based tax, where the final consumer bears the tax burden. Total VAT revenues are typically reported by national tax authorities and are a key indicator of how much revenue the government generates from the VAT system over a specific period.

- Final Consumption: This is the total value of goods and services consumed in the economy. Final consumption includes both household consumption (such as goods, services, and other consumables purchased by households) and government consumption. It excludes intermediate consumption (i.e., goods and services used in the production of other goods and services) to avoid double-counting. Final consumption is generally calculated using national accounts data, which aggregate consumption across all sectors of the economy.

- Calculation of Effective VAT (EVAT): The formula for calculating Effective VAT is:

This ratio gives a measure of how much VAT revenue is generated for each unit of final consumption. It reflects the effectiveness of the VAT system in relation to the overall consumption in the economy. A higher EVAT value indicates greater efficiency in VAT collection, while a lower value could suggest inefficiencies in the VAT system, such as tax evasion, exemptions, or poor enforcement.

- High EVAT: A higher ratio implies that a larger proportion of consumption is being taxed, potentially indicating a more efficient and effective VAT system.

- Low EVAT: A lower ratio suggests that VAT revenues are not in line with consumption levels, which could be due to various factors like loopholes in the VAT system, inadequate compliance, or a large informal sector.

Total VAT Revenues are sourced from UNU WIBER 2020 (GRD) while the Final Consumption is taken from the World Bank.

4.3. System GMM Results

Table 4 displays the estimation outcomes for the dynamic panel data using a system GMM estimator (Blundell & Bond, 1998). However, Columns 1 to 6 of Table 4 depict the results without the interaction term. Column 7, on the other hand, presents the findings incorporating the interaction of EVAT with institutional quality, while Column 8 showcases the results involving the interaction of EVAT with ethnic fragmentation. The model specification and the reliability of our instrument are supported by the failure to reject the Hansen J test. However, the AR (1) test reveals a serial correlation between the error terms. Therefore, we re-estimate our model utilizing an adjusted instrument set. The AR (2) test shows that the error term does not exhibit serial correlation, confirming that our instruments are valid.6

Table 4.

SGMM Results.

As revealed in Table 4, the coefficients of the lagged predicted variable are significant and positive. This suggests that there is a high degree of time persistence in income inequality, further supporting the usefulness of the system GMM estimate approach. We observe that the coefficients of EVAT are positive and statistically significant. This suggests that a short-run increase in EVAT leads to an increase in income disparity. According to columns 1–8 of Table 2, a 1% increase in EVAT leads to a rise in inequality, ranging between 0.043% and 0.087% in the short term. Therefore, we conclude that EVAT increases income inequality in SSA.

Following Wooldridge (2013, p. 635), we calculate the long-term impacts of our variables.7 In particular, the long-run effect of EVAT exerts a positive and significant effect on inequality. A 1% increase in EVAT augments inequality between 1.131 and 4.578 units in the long run. However, the magnitude of the long-term effects is greater than that of the short-run effects. The results from columns 1–8 also reveal a positive and statistically significant association between institutional quality and inequality. On average, a 1%-point increase in institutional quality leads to a rise in income inequality (0.031% and 0.091%) in the short run. In the long run, however, the results indicate that a 1% increase in institutional quality increases inequality between 2.583 and 2.843 units. It is also noticed that the interaction of EVAT with institutional quality is positive and significant.8 A 1% increase in the interaction term increases inequality by 0.062% in the short run. Hence, the long-run findings demonstrate that the interaction term increases inequality by 1.878 units. It is observed from our results that GDPpc and inflation are insignificant in affecting income inequality in SSA. However, we also find that gender equality is insignificant. The insignificance of GDP, inflation, and gender equality in affecting income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) may stem from the region’s unique economic and institutional context. SSA’s structural factors, such as informal economies, reliance on commodity exports, and political instability, could weaken the typical relationship between these variables and inequality, suggesting that GDP and inflation alone may not fully capture the drivers of inequality in the region. Additionally, the insignificance of gender equality may reflect persistent cultural, social, and policy barriers that hinder women’s economic participation and equality in SSA. These barriers, along with factors like access to education, healthcare, or labor market participation, might limit the expected impact of gender equality on income distribution in the region (UNDP, 2017).

Also, ethnic fragmentation and educational inequality are positive and statistically significant in affecting inequality in SSA. In the short run, a 1% rise in ethnic fragmentation augments inequality between 0.079% and 0.099% while educational inequality increases inequality between 0.028% and 0.099%. In the long run, the findings show that ethnic fragmentation is insignificant while a 1% increase in educational inequality will result in a rise in income inequality (0.777 and 3 units). The interaction term of EVAT with ethnic fragmentation exerts a positive and significant effect on inequality. This indicates that a 1% increase in the interaction between EVAT and ethnic fragmentation leads to a 0.051% increase in inequality in the short run. However, the long-term result indicates that a 1% increase in the interaction between the two variables will result in a 1.416 units increase in inequality.

4.4. Discussion

We now focus on the relationship between the effective VAT (EVAT), institutional quality, inequality, and other variables, along with their implications. The effective VAT is calculated as total VAT revenues divided by final consumption, reflecting the economic incidence of the tax rather than its legal definition. It is assumed that the tax burden is transferred to end consumers, making final consumption an appropriate tax base. Table 4 presents the SGMM estimates for effective VAT, institutional quality, inequality, and other control variables.

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), an effective VAT exacerbates income inequality in both the short and long term, with a more pronounced effect over time. Initially, VAT’s regressive nature increases the cost of goods and services, disproportionately affecting low-income households and causing a noticeable but limited rise in income inequality (World Bank, 2020). Over time, this effect intensifies as the cost of living continues to rise, further straining low-income households and widening the income gap, while wealthier households more easily absorb these costs (OECD, 2020). This long-term impact is worsened by weak governance and inefficient public spending, hindering the effective use of VAT revenue for social programs (Transparency International, 2021). These findings support the Regressive Theory of VAT in SSA. To address these issues, policymakers should consider targeted VAT exemptions for necessities, strengthen social protection programs, and implement comprehensive tax reforms to increase reliance on progressive taxes (UNICEF, 2020; African Development Bank, 2019). Comparative studies from Latin America emphasize the need for robust redistributive policies to counteract VAT’s regressive impacts (Bird & Zolt, 2005; ECLAC, 2018). Addressing VAT’s long-term impact on inequality is crucial for economic stability and growth, as high inequality can lead to social unrest and reduced consumer spending (UNCTAD, 2019).

The findings show that institutional quality exacerbates inequality both in the short and long term in Sub-Saharan Africa representing a significant departure from conventional expectations, necessitating a nuanced interpretation. One plausible explanation could be that while robust institutions may contribute to overall economic progress, weak institutions like SSA may disproportionately favor specific societal segments, thereby exacerbating income disparities. For example, institutions might unintentionally provide preferential treatment to certain groups, such as the affluent or politically influential, resulting in heightened levels of inequality (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). The observed long-term impact of institutional quality on inequality being greater than its short-term effect suggests complex underlying mechanisms at play. One possible explanation could be the cumulative nature of institutional effects over time. While high-quality institutions may initially contribute to economic growth and development, their impact on inequality may become more pronounced as their effects compound over the long term (Kaufmann et al., 2009).

The interaction between effective VAT and institutional quality suggests that VAT’s impact on inequality depends on institutional quality. The interaction term between VAT and institutional quality on inequality is significantly positive, suggesting that the institution reinforces the positive effect of EVAT on inequality in SSA. This corresponds with Extractive Institutions, which centralize power and wealth in the hands of a select few, limit economic prospects for the majority, and frequently exhibit corruption and feeble adherence to legal norms. Consequently, this fosters economic stagnation and substantial income disparities. Therefore, weak institutions—such as corruption, lack of transparency, and ineffective governance—can undermine the progressiveness of VAT policies. In environments with poor institutional quality, VAT may become regressive, disproportionately burdening lower-income households, and exacerbating income inequality. Moreover, weak institutions may hinder the proper utilization of VAT revenues, limiting their impact on reducing inequality.

In this context, financial development further complicates the relationship between VAT and inequality. While financial development itself is not included in the model, it is important to recognize that a well-developed financial sector can improve tax collection efficiency, enhance financial inclusion, and provide the means for more inclusive economic growth. Without a strong financial sector, however, VAT may have limited positive effects on inequality, especially if it is not accompanied by broader economic policies that promote wealth distribution and access to financial services. Ultimately, the interaction between VAT, institutional quality, and inequality in SSA depends on the institutional framework within which these policies operate.

The unexpected findings of this study suggest that complex dynamics are at play. One potential explanation could be the regressive nature of VAT, compounded by discrepancies in how institutional quality impacts different societal groups. Despite VAT’s intended role as a broad-based consumption tax, its burden disproportionately affects lower-income households, who allocate a larger share of their income to consumption (Bird & Gendron, 2007). In settings where institutional quality is lacking, the implementation of VAT may worsen existing inequalities by placing a heavier financial strain on vulnerable populations.

Moreover, the heightened long-term impact of the interaction between VAT and institutional quality may arise from the cumulative effects of institutions over time. Initially, high-quality institutions, in conjunction with VAT, may contribute to economic growth and advancement. However, over time, the persistent influence of institutional quality could magnify its effect on inequality, resulting in entrenched disparities in income and wealth distribution (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2008).

Additionally, the varying capacity of institutions to address the redistributive effects of VAT may also play a role in the observed phenomenon. In areas where institutional quality is deficient, VAT revenues may be susceptible to misappropriation or misallocation, exacerbating the wealth divide between affluent and impoverished individuals (Gupta et al., 2002).

Understanding the persistent impact of VAT on inequality in SSA necessitates considering the variable of ethnic fragmentation and its interaction with VAT. Ethnic fragmentation initially exacerbates income inequality in the short term, as evidenced by social segregation and unequal access to resources within diverse communities (Alesina et al., 2003). However, in the long run, although ethnic fragmentation continues to influence income inequality positively, its significance diminishes statistically, likely due to enhanced social cohesion and the emergence of inclusive institutions that mitigate its effects over time (Montalvo & Reynal-Querol, 2005). Hence, policymakers should prioritize inclusive policies fostering social cohesion and equitable resource distribution across diverse communities (Alesina et al., 2003). Moreover, investments in inclusive governance structures and economic development initiatives can contribute to reducing income disparities along ethnic lines in the long term (Montalvo & Reynal-Querol, 2005). These findings resonate with empirical evidence and comparative studies, indicating that effective policies and institutional reforms have the potential to alleviate the initial impacts of ethnic diversity on income inequality (Fearon, 2003).

The interaction between VAT and ethnic fragmentation exacerbates income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) over both short and long timeframes, with the long-term consequences being more pronounced. In the short term, the amalgamation of high VAT rates and ethnic diversity amplifies income disparities due to factors such as unequal resource allocation and social segregation prevalent in ethnically fragmented societies (Alesina et al., 2003; Bird & Zolt, 2005). Over time, these disparities are compounded by the sustained regressive effects of VAT, leading to deeper and more entrenched income inequalities as ethnic divisions and unequal tax burdens perpetuate economic disadvantages (Montalvo & Reynal-Querol, 2005). To address these challenges, policymakers must implement measures to alleviate the regressive impact of VAT, including the adoption of progressive tax policies and ensuring that VAT revenues support social programs for marginalized groups, while concurrently promoting social cohesion and reducing ethnic tensions (Alesina et al., 2003; Bird & Zolt, 2005). In the long term, strategies should prioritize inclusive governance, expand educational opportunities, and ensure equitable resource distribution to mitigate the compounded effects of VAT and ethnic fragmentation, thereby fostering inter-ethnic integration and reducing income disparities (Montalvo & Reynal-Querol, 2005). These findings are consistent with empirical evidence from other regions, underscoring the enduring influence of tax policies and ethnic diversity on income inequality and emphasizing the need for comprehensive policy approaches that address both tax fairness and social cohesion (Fearon, 2003; Bird & Zolt, 2005).

Educational disparities play a significant role in fueling income inequality in SSA, a phenomenon that is consistent with the Skill-Biased Technological Change (SBTC) theory. This theory posits that variations in skills among workers lead to disparities in productivity and income levels. However, the impact of these inequalities is more pronounced over the long term compared to the short term. In the immediate sense, unequal access to quality education translates into immediate income gaps, as individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds struggle to secure well-paying employment opportunities. Yet, as time progresses, these educational discrepancies compound, resulting in deeper-rooted income disparities. The cumulative advantages conferred by education mean that individuals lacking educational opportunities face enduring economic setbacks, thus widening the income divide. Therefore, addressing educational inequality emerges as a critical imperative for policymakers. Strategies should entail augmenting funding for education, implementing targeted interventions, enhancing educational infrastructure, and fostering inclusive policies. Supporting this stance, empirical evidence from other regions, such as Latin America, underscores the imperative for equitable education systems in ameliorating income inequality (UNESCO, 2018; World Bank, 2020; UNICEF, 2019; OECD, 2020; Black & Devereux, 2011; Psacharopoulos & Patrinos, 2018; Bourguignon et al., 2007; Milanovic, 2016).

5. Conclusion and Policy Implications

Despite the global economy growing at an ever-increasing rate in recent years, income disparity has been increasing in both developing and developed economies. The drivers of income disparity have been studied in existing literature, including the tax system. However, the empirical evidence on the relationship between the tax system and income disparity has so far yielded conclusions that are strongly contradictory, and institutional quality has received little attention. Therefore, this study investigates the joint impacts of EVAT (calculated as total VAT revenues divided by final consumption, which reflects the economic incidence of the tax rather than its legal definition as mostly used in the literature) and institutional quality9 on income disparity in SSA. We use SGMM to account for the potential endogeneity. This paper first tests whether EVAT increases income inequality in SSA in both the short and long run. Second, we examine whether the relationship between EVAT and income inequality depends on institutional quality in both the short and long term. We find that EVAT augments the income gap in both the short and long run. With this result, the Regressivity Theory of VAT, which states that a rise in VAT leads to a rise in income inequality in SSA, is confirmed. However, the impact of the long term is stronger than that of the short run. In addition, the findings show that institutional quality reinforces the positive effect of EVAT on income disparity in SSA. This suggests that institutional quality plays a main role in augmenting the impact of EVAT on income inequality. To better understand the relationship between EVAT and higher and persistent income disparity in SSA, this study contributes to the literature by including some significant control variables such as gender equality, educational inequality, ethnic fragmentation, etc. Specifically, we find that ethnic fragmentation is one of the significant factors that impedes effective VAT to lower income disparity in the short and long run in SSA. In addition, educational disparity plays a significant role in driving income inequality in SSA, aligning with SBTC theory.

Drawing from the findings that effective VAT exacerbates income inequality over both short and long timeframes, with a heightened impact observed in the latter, and that institutional quality reinforces this pattern, along with additional insights into the consequences of ethnic fragmentation and educational disparities, the following policy proposals are suggested:

- Revise VAT Policies: Reevaluate and adjust VAT policies to mitigate their adverse effects on income distribution. This could entail implementing targeted exemptions or reduced rates for essential goods and services predominantly utilized by lower-income households. Additionally, explore avenues for incorporating progressive elements into the VAT framework to ensure a fairer distribution of the tax burden across various income levels.

- To address the persistent issue of income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), strengthening institutional quality is essential. Effective governance, the rule of law, and administrative efficiency must be prioritized to improve tax collection practices and ensure the efficient use of VAT revenues. Countries with stronger institutions are better positioned to reduce corruption, ensure that tax revenues are fairly allocated, and invest in social programs that target marginalized communities. Drawing from successful examples in other regions, SSA could consider policies such as enhancing transparency in public spending, promoting fiscal decentralization to improve local governance, and implementing more rigorous tax compliance measures, especially targeting the informal sector. For instance, reforms in Rwanda and Botswana have successfully bolstered tax revenues and enhanced social welfare systems by improving institutional frameworks and governance (Kaufmann et al., 2020). Additionally, strengthening the judiciary and public administration would ensure that VAT revenues are used effectively for poverty alleviation programs. Such reforms would improve the redistributive capacity of the tax system, thereby contributing to a more equitable distribution of wealth and reducing the regressive impacts of VAT in SSA.

- Address Ethnic Fragmentation: Develop strategies focused on fostering social cohesion and ameliorating ethnic divisions to promote a more inclusive society. Initiatives like inter-ethnic dialogue, cultural exchange programs, and affirmative action measures can serve to bridge societal gaps and facilitate a more equitable distribution of resources and opportunities.

- Combat Educational Inequality: Implement measures aimed at addressing educational disparities and expanding access to quality education for all segments of society. This may involve increased investment in educational infrastructure, expanded schooling opportunities in underserved regions, and targeted assistance for disadvantaged students through scholarships and financial aid programs.

- Enhance Tax System Efficiency: Invest in enhancing the efficiency and efficacy of the tax system by modernizing tax administration processes, fortifying compliance mechanisms, and clamping down on tax evasion and avoidance. Strengthening tax enforcement can ensure the equitable collection of VAT revenues and contribute to narrowing income disparities.

- Foster Inclusive Economic Growth: Promote policies conducive to fostering inclusive economic growth and creating pathways for income generation and wealth accumulation across diverse segments of the population. This could entail supporting the development of small and medium-sized enterprises, investing in vocational training initiatives, and fostering entrepreneurship opportunities in marginalized communities.

- Collaborate Internationally: Engage in collaboration with international organizations and development partners to exchange knowledge, expertise, and financial resources aimed at addressing income inequality and enhancing tax systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Participation in regional and global initiatives can facilitate the implementation of policy reforms geared towards achieving sustainable development goals and fostering a more equitable society.

- The gray economy in Sub-Saharan Africa plays a critical role in shaping the effectiveness of VAT enforcement and influencing income inequality. It includes informal economic activities, ranging from small businesses offering basic services to large, unreported capital-intensive operations, and operates outside the formal taxation system. This undermines VAT enforcement by reducing the taxable base, as many informal businesses are not registered, leading to lower tax revenues. This, in turn, limits the government’s ability to fund public services or redistributive programs aimed at reducing inequality.

- The impact of the gray economy on VAT enforcement varies across sectors. Small, labor-intensive businesses, such as street vendors, typically do not generate significant VAT liabilities, meaning VAT collection is less affected in these areas. However, larger, capital-intensive sectors (e.g., manufacturing, mining, construction) contribute significantly to tax evasion due to underreporting, which reduces public revenues and exacerbates income inequality by limiting the resources available for redistribution.

- VAT is a regressive tax, disproportionately impacting lower-income households who spend a larger share of their income on consumption. In economies where the gray economy is dominated by capital-intensive entities, this regressive effect is intensified, as wealthier individuals and businesses evade VAT by not declaring income, leaving poorer consumers to bear the tax burden. However, if the gray economy consists primarily of low-cost services, such as food and household labor, the regressive impact of VAT may be somewhat mitigated, as these services tend to place a smaller burden on poorer households.

- While the gray economy does not directly contribute to formal income redistribution, it provides supplementary income through informal activities like subsistence farming or street vending. These informal activities help supplement household incomes, offering a form of substitute redistribution that improves purchasing power but does not address nominal income inequality.

- In the long term, the gray economy hampers the ability to collect sufficient tax revenue, making it harder to invest in essential public services like education and healthcare. In the short term, it may alleviate income inequality by providing low-cost services, but its impact on overall inequality depends on the sectors involved in the informal economy.

By implementing these policy recommendations, policymakers can address the underlying drivers of income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa, including the impact of VAT, institutional quality, ethnic fragmentation, and educational disparities, thus fostering a more equitable and inclusive society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.P.V.; methodology, N.N. and T.P.V.; software, N.N.; validation, N.N.; formal analysis, T.P.V.; investigation, N.N. and T.P.V.; resources, N.N. and T.P.V.; data curation, T.P.V.; writing—original draft preparation, T.P.V.; writing—review and editing, T.P.V. and N.N.; visualization, N.N. and T.P.V.; supervision, N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

No applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study can be found at: (i) SWIID (Standardized World Income Inequality Database–Frederick Solt); UNU Wiber; WDI-World Bank.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

A1. List of countries: Botswana, Lesotho, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritius, Mauritania, Senegal, Swaziland, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Tanzania, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe, South Africa.

Notes

| 1 | The list of countries is in the Appendix A. |

| 2 | (1995–1997, 1998–2000, 2001–2003, 2004–2006, 2007–2009, 2010–2012, 2013–2015, 2016–2018, 2019–2021). |

| 3 | Over years, income disparity slowly varies within countries. This shows that some unobserved factors may be responsible for this time persistence. If these factors are associated with our regressors in this context, fixed-effects estimates are biased. The lag of income disparity must be included as an regressor in order to address this problem. |

| 4 | For discussion on the long-run propensity in distributed lag models, see Wooldridge (2013). |

| 5 | Causality test results will be made available upon request. |

| 6 | To avoid the issue of too many instruments in the system GMM estimator, we used EVAT as instruments. This decision is also influenced by the criterion that the number of instruments should, in theory, be less than the number of countries (Roodman, 2009) and the AR (3) test results. Our key results are robust to limiting the endogenous variable utilized as instruments. |

| 7 | Note that we interpret only the long run coefficients for significant short run coefficients. The long run impacts for the Kth parameter is computed as: . Where is the short run coefficient and represents the lag of the dependent variable. Stata command for the long run: nlcom (_b[indep var])/(1-_b[L1.dep var]). Since the effect of government spending using VAT may take several years before it has an impact on institutional quality outcomes and the period is quite long enough, we use 3 year of lag instead of 1 year of lag. |

| 8 | We also observe that the introduction of interaction term in columns 7 and 8 strenghen the model. |

| 9 | We utilized PCA to a composite index for institution quality index including control of corruption, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and voice and accountability. |

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2013). Democracy, redistribution and inequality. Working Paper 19746. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w19746 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2008). The role of institutions in growth and development. Review of Economics and Institutions, 1(2), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). The Narrow corridor: States, societies, and the fate of liberty. Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adandohoin, G. (2021). Analysis of the impact of economic policies on poverty reduction in developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 58(4), 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- African Development Bank. (2010). African economic outlook 2010: Sub-saharan Africa’s challenges. African Development Bank Group. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/en/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- African Development Bank. (2019). African economic outlook. African Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu, B. (2010). An examination of the link between tax administration and value added tax (VAT) compliance in Ethiopia [Master’s thesis, School of Graduate Studies, Addis Ababa University]. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A., Baqir, R., & Easterly, W. (2003). Ethnicity and economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A., & Ferrara, E. L. (2005). Ethnic diversity and economic performance. Journal of Public Economics, 43(3), 762–800. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w10313 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Alesina, A., Ferroni, F., & Pinna, A. (2020). Ethnic fragmentation and economic inequality. Journal of Economic Surveys, 34(3), 595–613. [Google Scholar]

- Aremo, A. G., & Abiodun, S. T. (2020). Causal nexus among fiscal policy, economic growth and income inequality in Sub Saharan African countries. African Journal of Economic Review, 8(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R. (2020). VAT and income inequality. Economic Policy, 35(3), 471–493. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, R. M., & Gendron, P.-P. (2007). The VAT in developing and transitional countries. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, R. M., & Zolt, E. (2005). Redistribution via taxation: The limited role of the personal income tax in developing countries. School of Law, Law & Economics Research Paper Series No. 05-22. University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Black, S. E., & Devereux, P. J. (2011). Recent developments in intergenerational mobility. Handbook of Labor Economics, 4, 1487–1541. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, F. (2020). The globalization of inequality. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, F., Ferreira, F. H. G., & Menéndez, M. (2007). Inequality of opportunity in Brazil. Review of Income and Wealth, 53(4), 585–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, N., & Nandwani, B. (2018). Ethnic fragmentation, public good provision and inequality in India, 1988–2012. Oxford Development Studies, 46(3), 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2021). World inequality report 2022. World Inequality Lab. [Google Scholar]

- Chletsos, M., & Sintos, A. (2023). Financial development and income inequality: A meta–analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys, 37(4), 1090–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogneau, D., & Dupraz, Y. (2015). Income distribution, natural resources and public policies. In Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2, pp. 659–758). North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, J., & Sturm, J. E. (2017). Finance and income inequality: A review and new evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 50, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECLAC. (2018). Tax policy and income redistribution in Latin America: Potential and limits. ECLAC. [Google Scholar]

- Emran, M. S., & Stiglitz, J. E. (2005). On selective indirect tax reform in developing countries. Journal of Public Economics, 89(4), 599–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, J. D. (2003). Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D., Lynch, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2019). Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Management Science, 65(10), 4467–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, N., & Morrissey, O. (2005). Distribution and poverty impacts of tax structure reform in developing countries: How little we know. Development Policy Review, 23, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., Davoodi, H., & Alonso-Terme, R. (2002). Does corruption affect income inequality and poverty? Economics of Governance, 3(1), 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF. (2015). Fiscal policy and income inequality. IMF Policy Paper. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. (2021). World economic outlook: Inflation and income inequality. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y., & Lim, G. (2020). Corruption and tax evasion. Journal of Development Economics, 145, 102500. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, J. (2019). What is a value-added tax (VAT)? [online] Investopedia. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/v/valueaddedtax.asp (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2009). Governance matters VIII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996–2008. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4978. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2020). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5430. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, M. (2008). VAT, tariffs, and withholding: Border taxes and informality in developing countries. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 1892–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, M., & Lockwood, B. (2010). The value added tax: Its causes and consequences. Journal of Development Economics, 92, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozuharov, S., Miteva-Kacarski, E., Dzambaska, E., & Temjanovski, R. (2015). Fiscal policy and economic growth: The Case of Macedonia. Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences, 156, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kripfganz, S., & Schwarz, C. (2019). Estimation of linear dynamic panel data models with time-invariant regressors. Journal of Econometric Methods, 8(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki, T. (2011). Dynamics of income inequality and mobility in developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 96(2), 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, N. (2020). Inequality and poverty in the Middle East and North Africa: The impact of the COVID-19 crisis. Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Malla, M. H., & Pathranarakul, P. (2022). Fiscal policy and income inequality: The critical role of institutional capacity. Economies, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, P. (1995). Corruption and growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(3), 681–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal Political Economy, 89(5), 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messy, M. A., & Ndjokou, I. M. M. (2021). Taxation and income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economics Bulletin, 41(3), 1153–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Milanovic, B. (2016). Global Inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo, J. G., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2005). Ethnic polarization, potential conflict, and civil wars. American Economic Review, 95(3), 796–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M. (2007). How does taxation affect the quality of governance? Institute of Development Studies Working Paper, 280. Institute of Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrave, R. A. (1959). The theory of public finance (pp. 532–541). McGraw Hill Book Co. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2020). Education inequality and social mobility. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2021). Income inequality: The gini coefficient. OECD Economic Outlook. [Google Scholar]

- Padhan, H., Prabheesh, K. P., & Padhan, P. C. (2022). Does tax structure affect income inequality? Evidence from G7 countries. Economic Analysis and Policy, 73, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psacharopoulos, G., & Patrinos, H. A. (2018). Returns to investment in education: A decennial review of the global literature. Education Economics, 26(5), 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (2014). When ideas trump interests: Preferences, worldviews, and policy innovations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(1), 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, C. S., David, O. O., & Voto, T. P. (2024). Institutional quality effect of ICT penetration: Global and regional perspectives. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 27(1), 5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemrod, J., & Velayudhan, T. (2022). The VAT at 100: A retrospective survey and agenda for future research. Public Finance Review, 50(1), 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solt, F. (2019). Measuring income inequality across countries and over time: The Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) Version 8.0, February 2019. Harvard Dataverse. [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi, V., & Zee, H. H. (2000). Tax policy for emerging markets: Developing countries. National Tax Journal, 53(2), 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y. (2019). Educational inequality and its determinants: Evidence for women in nine Latin American countries, 1950s–1990s. Revista de Historia Economica-Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, 37(3), 409–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International. (2021). Corruption perceptions index. Transparency International. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. (2019). Economic development in Africa report. UNCTAD. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2018). Global education monitoring report 2019: Migration, displacement, and education–Building bridges, not walls. UNESCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. (2019). The State of the World’s Children 2019: Children, food and nutrition–Growing well in a changing world. UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. (2020). Social protection in Sub-Saharan Africa. UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. (2017). Income inequality trends in Sub-Saharan Africa: Divergence, determinants, and consequences. UNDP. [Google Scholar]

- UNU-WIDER. (2021). World income inequality database: Key findings and insights. United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research. Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2013). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (5th ed.). South-Western Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2020). The changing nature of work in Africa. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- World Inequality Database. (2023). Global inequality indicators. World Inequality Lab. Available online: https://wid.world/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).