4.1. Public Expenditure and Economic Growth

What is the theoretical effect of the level of public expenditure on income and consumption per head? Equations (A6), (A9), (A11) and (A14) in

Appendix A imply the following levels of income and consumption per head:

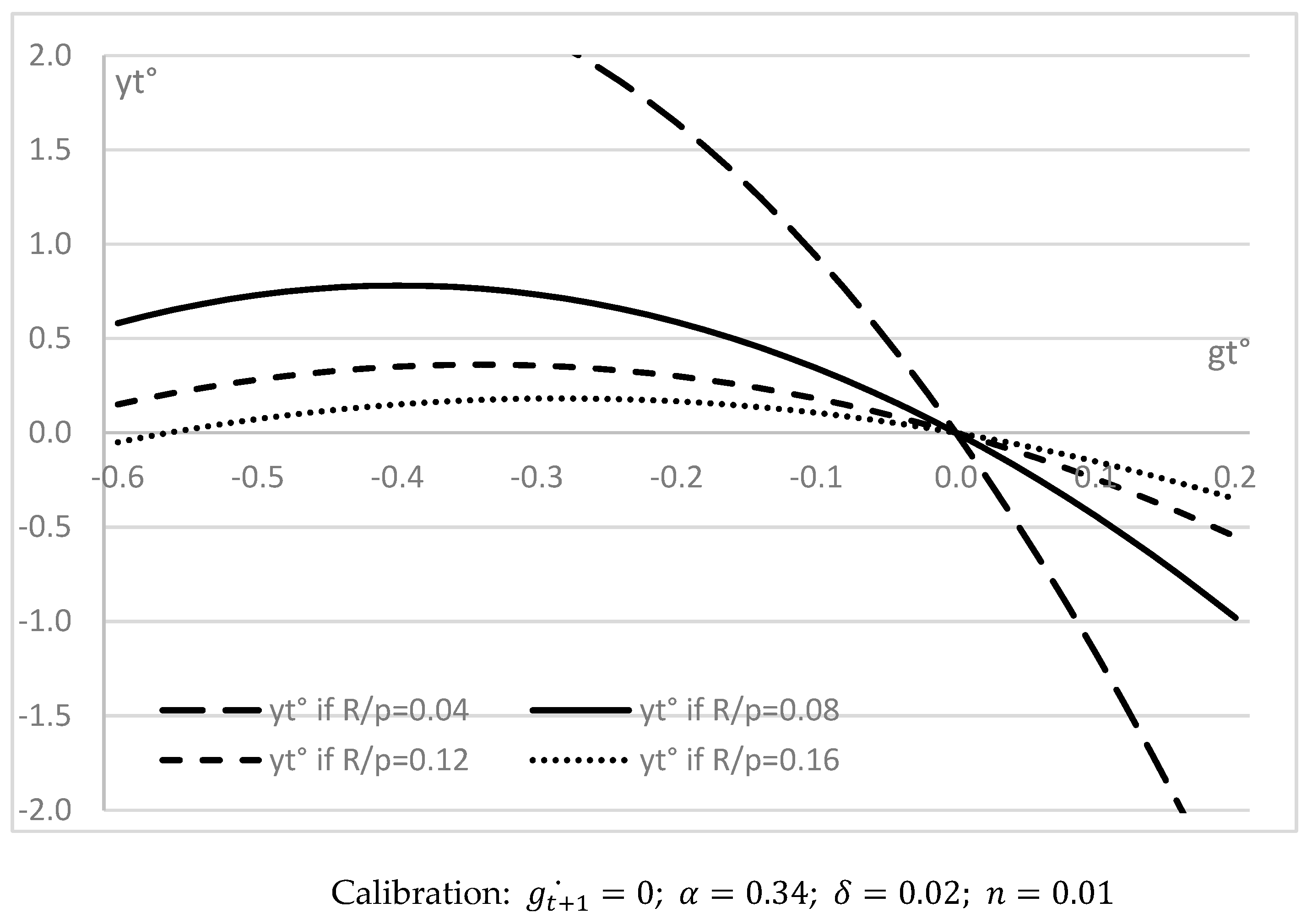

Therefore, Equations (17) and (19) show that even if public consumption expenditures benefit private consumption and contribute to private well-being, they harm global economic activity. Indeed, using also Equation (24), we obtain

Therefore, public consumption expenditure harms all the more economic activity as the preference is higher for private than for public consumption (

) [see

Figure 1]. Indeed, according to Equation (21), public consumption expenditure could only be beneficial if

Households’ preference for private consumption is particularly weak in comparison with their high appetence for public expenditure: according to our basic calibration.

The real return on capital is particularly weak: , according to our basic calibration.

However, these conditions are empirically very weakly plausible, and therefore, public consumption expenditure is mainly detrimental to economic activity. On the contrary, public investment expenditure appears beneficial to economic activity. Indeed, using Equation (22), we obtain

Therefore, according to Equation (20), our model shows that public investment expenditure decreases private consumption per head. However, according to Equation (18), public investment expenditure also increases income per head provided

. Moreover, according to Equation (22), the budget multiplier for public investment expenditure is even higher than one, provided public investment expenditure is sufficiently limited: (

) according to the basic calibration of our model [see

Figure 1]. Therefore, our modeling conforms with the economic literature (see

Section 2), distinguishing between public consumption expenditure, which could be harmful, and public investment expenditure, which would be mainly growth-enhancing.

Furthermore, Equations (17) to (20) imply the following level of economic growth, which is identical in the case of growth of public consumption (

) or public investment (

) expenditure per head:

Therefore, public consumption expenditure, public investment expenditure, capital stock, and private consumption per head all increase at the same rate according to Equation (24). As in

Afonso and Tovar-Valles (

2011), the capital stock positively affects the real GDP per head. Increasing productive (

) or even unproductive (

) public spending is beneficial to improve the growth of private consumption, and the capital stock (k) strongly positively impacts economic growth [see Equations (23) and (24)]. Nevertheless, according to Equation (23), economic growth can be higher or lower than this common average growth rate of economic variables per head. Indeed:

Therefore, the effect of the variation of investment or consumption public spending per head on economic growth is ambiguous. The economic literature has often underlined a U-shaped relationship between public expenditure and economic activity (see

Section 2). However, the contribution of our paper is to show that this relation could also exist between variations of public expenditure and economic growth rates. Indeed, according to Equation (23):

However, this situation is highly improbable, as according to our basic calibration, the future anticipated increase in public expenditure should be above ( if (). More precisely, the increase in public expenditure could only be beneficial for developing countries, during the limited period of catch-up where the increase in public expenditure per head is very strong in conformity with their development process.

Therefore, the optimal variation of public expenditure per head depends on capital returns, the depreciation rate of capital, the population growth rate, and the capital share in the production function (see below). However, according to our basic calibration, public expenditure should decrease, for example, by about (−0.4%) to allow a maximal economic growth of (0.78%) if (R/p = 0.08) [see

Figure 2].

Moreover, we can study the sensitivity analysis of the robustness of our results to the calibration of the parameters of our model. According to Equation (21), provided [], economic growth is higher if the increase of the future anticipated capital per head is higher than the increase of the current capital per head (), or if capital returns decrease ( < 0). Nevertheless, the influence of the various parameters of our model on economic growth depends on these positive or negative variations of capital and public spending per head. Therefore, our parameters mainly influence the absolute level of revenue or consumption per head.

Public investment expenditure increases income per head but decreases private consumption per head, whereas public consumption expenditure decreases income per head but increases private consumption per head. Nevertheless, according to Equations (17) to (20), public consumption expenditure is less detrimental to economic growth if households’ preferences for public services () are high; however, private consumption is then more limited. Indeed, suppose the preference for public services is high. In that case, a high level of public consumption expenditure provides the same utility to households as a weaker level of private consumption in Equation (1). A high household preference for public services also reduces the beneficial effect of public investment expenditure on economic growth.

Public investment expenditure increases income per head but decreases consumption per head. Then, a higher elasticity of intertemporal substitution (θ) or a higher inverse of the Frisch elasticity of labor supply (φ) is beneficial. Indeed, the increase in income per head is accentuated, whereas the decrease in private consumption is reduced. The increase in income head is also accentuated if the capital share in the production function (α), the capital depreciation rate (δ), or the population growth rate (n) is high, whereas the effect of the real return on capital (R/p) is more ambiguous.

On the contrary, public consumption expenditure decreases income per head but increases consumption per head. Then, a higher elasticity of intertemporal substitution (θ) accentuates the decrease in revenue per head, as well as the increase in private consumption. A higher inverse of the Frisch elasticity of labor supply (φ) worsens the decrease in income per head. A higher capital share in the production function (α), capital depreciation rate (δ), or population growth rate (n) also worsens the decrease in income per head. In contrast, the effect of the real return on capital (R/p) is more ambiguous.

The economic literature often assimilates the study of the consequences of the size of the government on economic growth to the analysis of the level of public expenditure. However, beyond this analysis present in

Afonso and Tovar-Valles (

2011) for example, our theoretical model also allows us to study the effect of various taxation rates, on the side of fiscal resources.

4.2. Fiscal Resources and Economic Growth

Regarding fiscal resources, taxation reduces the incentive to produce, production realized or labor supplied. However, taxation also increases the production of efficient public services and the productivity of production factors. Instead of distinguishing between distortionary (proportional to output, affecting investment choices) and non-distortionary (lump-sum) taxation, we consider three different kinds of taxation rates: on consumption, labor, and capital. In our model, consumption taxation rates affect capital, private consumption, and economic growth rates. Indeed, Equation (A16) in

Appendix A implies

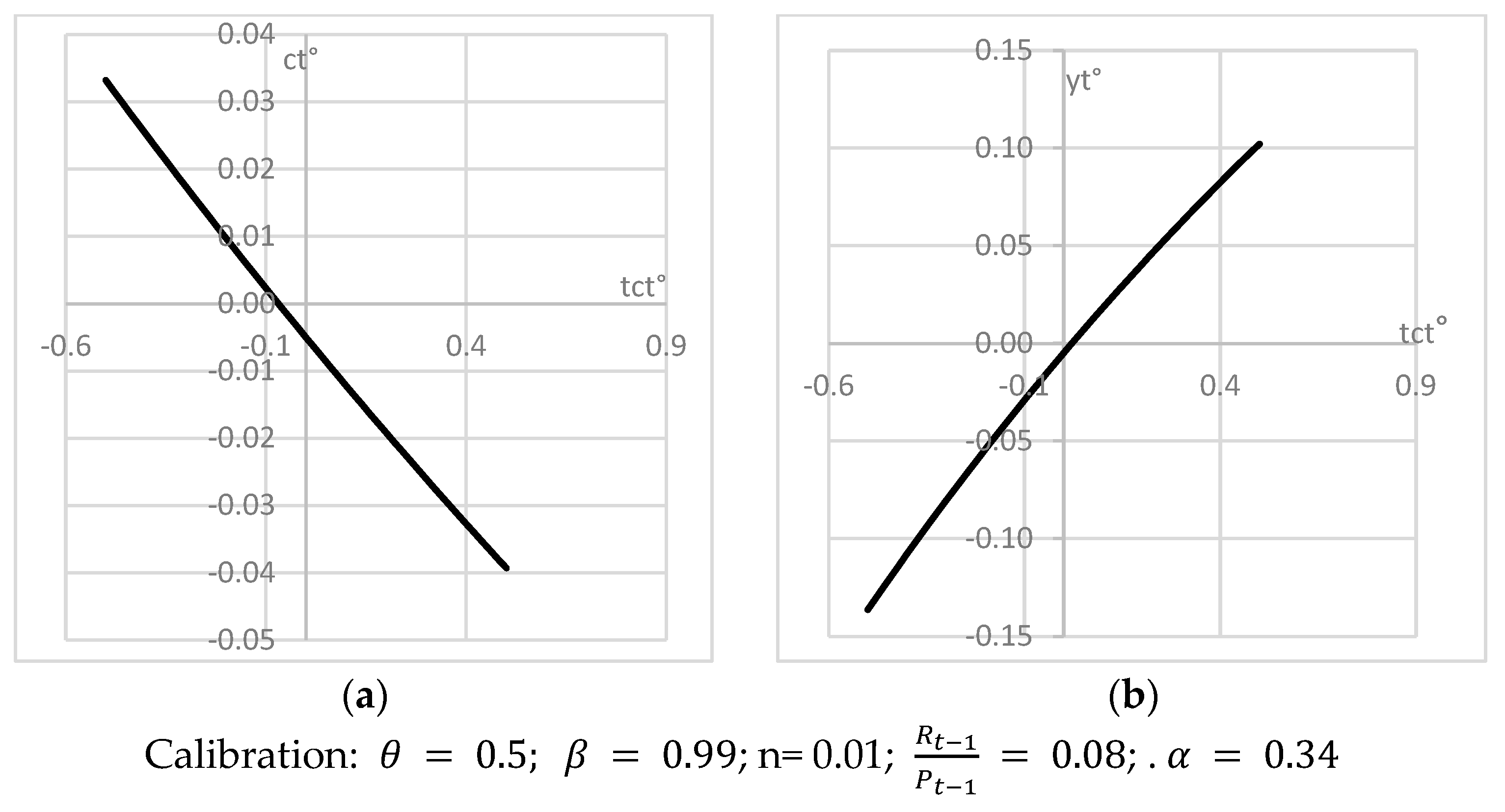

Therefore, according to Equations (27) and (28), a high consumption taxation rate harms private consumption growth if this tax rate increases, but it is beneficial if it decreases. An increase in the consumption taxation rate is always harmful to private consumption growth, whereas a decrease is always helpful, whatever the absolute level of the consumption taxation rate. The relation would be linear, but consumption taxation rate variations would only marginally modify private consumption growth [see

Figure 3].

On the contrary, regarding economic growth, Equation (A20) in

Appendix A implies

Therefore, even if it is detrimental to private consumption, increasing the current consumption taxation rate (

) seems beneficial to economic growth [see

Figure 3]. Therefore, increasing the share of fiscal resources collected by way of consumption taxes, in comparison with taxing capital or labor, could benefit global economic growth.

Moreover, in the short run as in the long run, according to Equations (26) and (29), private consumption and global economic activity growth increase with the time discount factor (β), but they decrease with the elasticity of intertemporal substitution (θ) []. Indeed, the higher the time discount factor, the higher the preference for future consumption and sparing, and the higher the capital growth rate per head. Furthermore, in the short run, three factors can modify economic growth. According to Equation (29), the real return on capital (R/p), or the capital share in the production function (α), only marginally modifies the economic growth rate depending on the variation of the consumption taxation rate. According to Equation (29), a third factor influencing economic growth in the short run is population growth (n). However, demographic growth also only marginally modifies economic growth depending on the variation of the consumption taxation rate. Moreover, these variables do not affect private consumption or economic growth in the long run.

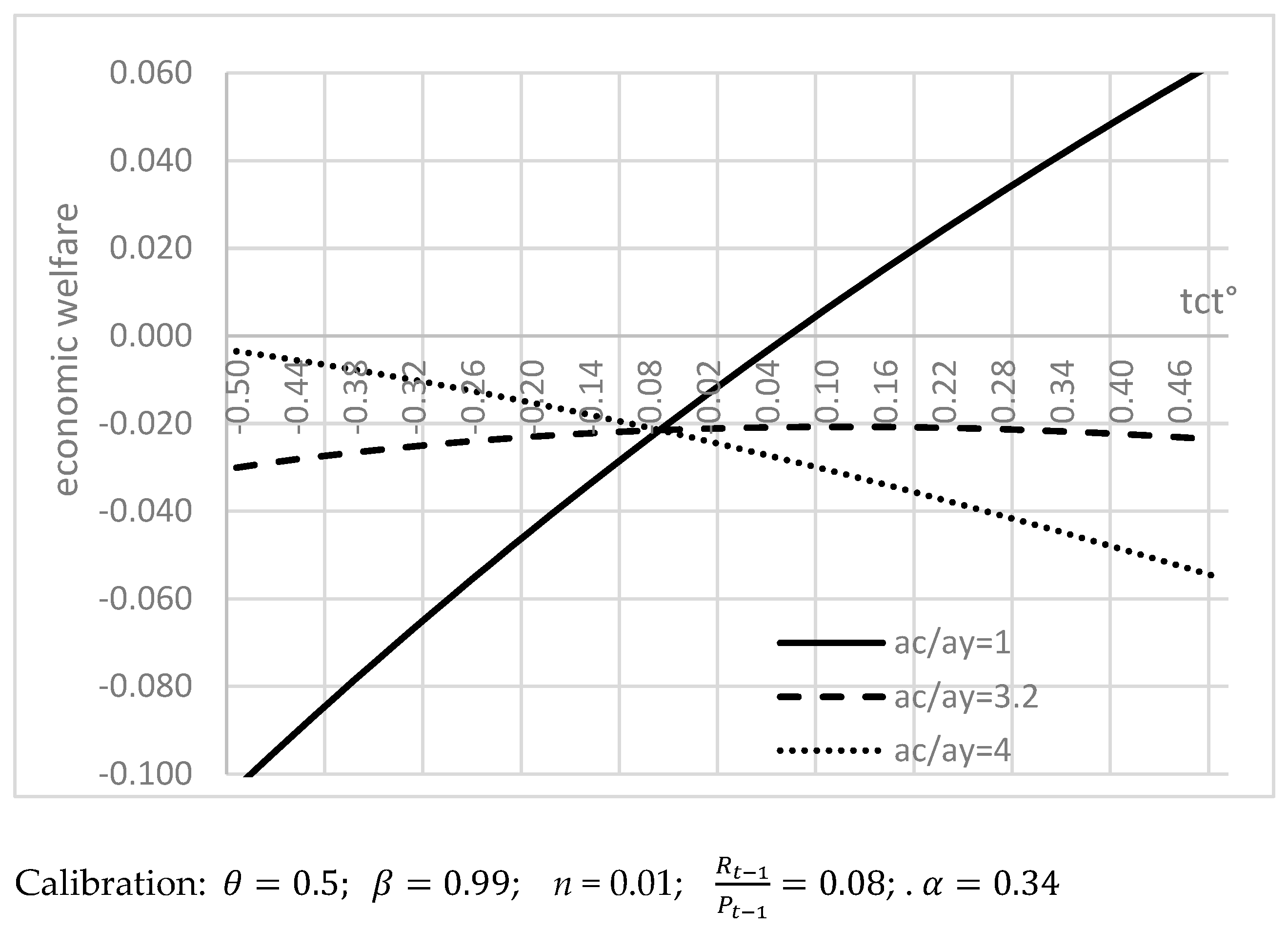

In this context, economic authorities could be tempted to arbitrate between increasing private consumption (

) and global economic growth (

). Therefore, using Equations (26) and (29), we obtain the following average well-being in Equation (30):

Therefore, as mentioned above, increasing the consumption taxation rate could benefit global economic growth, whereas moderating the consumption taxation rate could benefit private consumption. So, it is only in the intermediate case of an arbitrage slightly in favor of private consumption (

) that there could be an inverted U-shaped relation between the increase of the consumption taxation rate and an indicator of economic well-being, with a maximal taxation rate to collect the optimal level of fiscal resources [see

Figure 4].

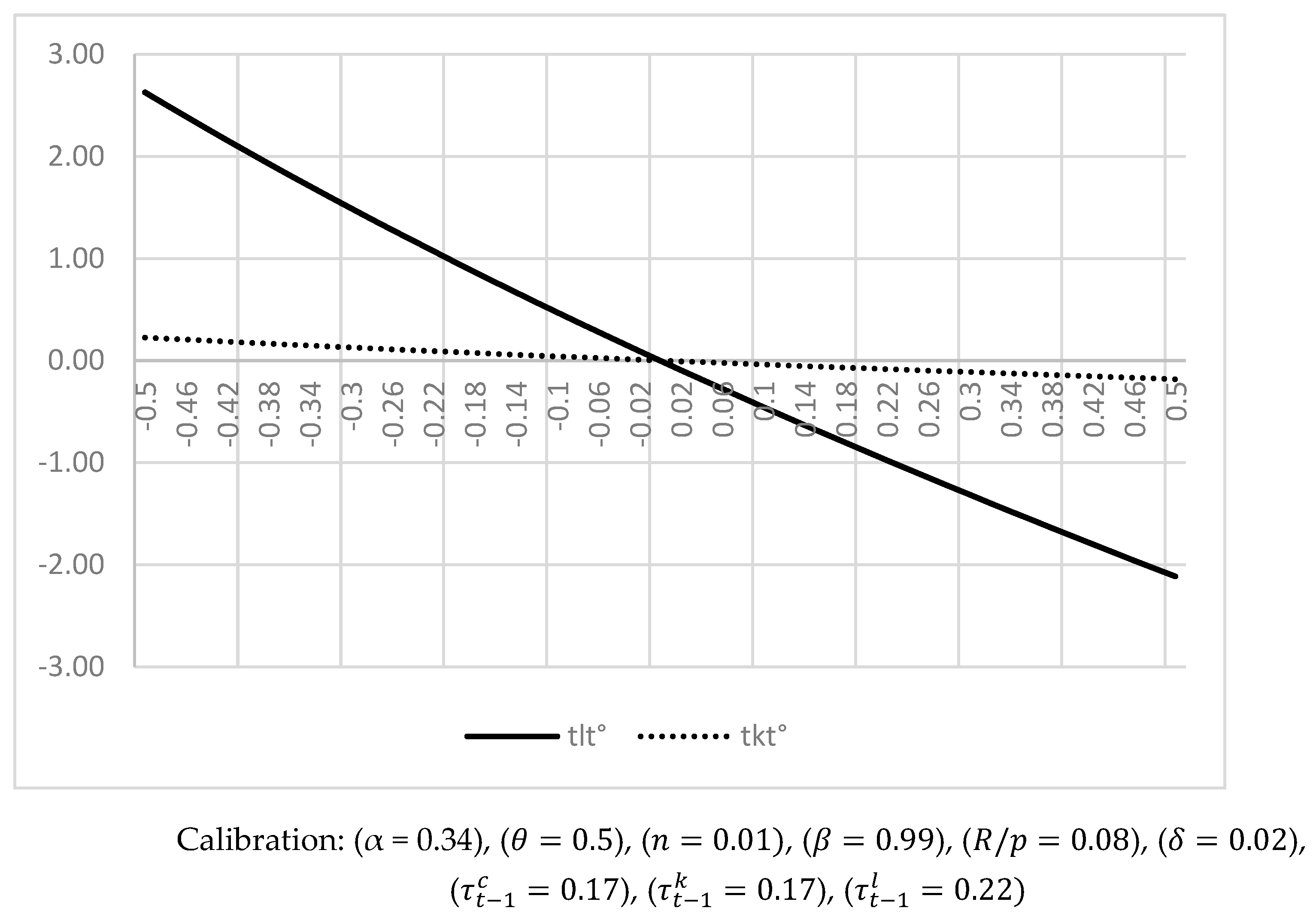

Furthermore, in these conditions, if the government’s goal is to target an equilibrium budget, a higher consumption taxation rate should be compensated with a decrease in the labor or capital taxation rate. Therefore, according to Equation (A22) in

Appendix A, these variations should be such as

Therefore, to compensate for a higher (smaller) consumption taxation rate, beneficial to economic growth, and to equilibrate the budget balance, the decrease (increase) in the labor taxation rate could be more accentuated than the decrease (increase) in the capital taxation rate [see

Figure 5]. Indeed, according to the parameter (α), the labor share in the production function is about twice higher than the capital share in the production function. The absolute levels of the capital or labor taxation rates have no effect in the long run, as Equation (30) is always verified. However, if the consumption taxation rate (

) is higher, compensatory variations in the labor or capital taxation rates are both more accentuated. Moreover, if the labor taxation rate (

) is higher, variations in the labor taxation rate are strongly accentuated, whereas variations in the capital taxation rate are much more moderate. On the contrary, if the capital taxation rate (

) is higher, variations in the capital taxation rate are only very slightly accentuated, whereas variations in the labor taxation rate are significantly more moderate.

Furthermore, according to Equation (31), optimal variations in the labor or capital taxation rates also depend on variations of other variables. Indeed, if the capital share in the production function (α) increases, variations in the labor taxation rates should be reduced, whereas variations in the capital taxation rates should be accentuated. Moreover, if the real capital returns (R/p) or if the intertemporal elasticity of substitution (θ) increase, variations in the labor and capital taxation rates should be accentuated. On the contrary, if the capital depreciation rate (δ), the population growth rate (n), or the time discount factor (β) increases, variations in the labor or capital taxation rates should be mitigated. Therefore, a higher consumption taxation rate is likely to favor a higher global economic growth rate. The capital and mainly the labor taxation rate could then simultaneously be reduced without consequences on global fiscal resources and the budget. Nevertheless, the intensity of the decrease allowed in capital or labor taxation rates depends on other economic variables.

4.3. Empirical Observations

The current paper is theoretical, and we leave for future research the empirical verification by econometrical methods of our hypotheses. However, a first look at empirical data show that these theoretical hypotheses could be verified. For the European Union, these data come from the AMECO database for global economic growth rates, final consumption expenditure, and gross fixed capital formation of the governments in 2024. Data come from the website of the European Commission for the year 2022 (last available data) for the implicit tax rate on consumption.

In 2024, the average annual GDP growth rate was 1.12% in the European Union, whereas for the governments, on average, final consumption expenditure represented 21.5% of GDP and gross fixed capital formation 3.7% of GDP at current market prices. However, in conformity with our hypotheses, we can note that economic growth was higher in a group of countries where the share of public investment expenditure was high. Indeed, public gross fixed capital formation and economic growth were both higher than the European average in Croatia (respectively, 5.7% and 3.4%), Romania (5.7% and 1.91%), Slovenia (5.2% and 1.5%), Poland (5% and 2.96%) or in Greece (4.9% and 2.28%). On the contrary, public gross fixed capital formation and economic growth were both weaker than the European average in the Netherlands (respectively, 3.1% and 0.63%), Germany (3% and 0.01%), or Ireland (2.5% and −0.18%). Moreover, economic growth was also higher in a group of countries where public consumption expenditure was weak. Indeed, the share of public final consumption expenditure in GDP was weak in a group of countries where economic growth was higher than the European average: Portugal (respectively 16.8% and 1.93%), Malta (17.2% and 5%), Lithuania (18.1% and 2.43%), Cyprus (18.6% and 3.29%), Romania (18.8% and 1.91%), Greece (19.2% and 2.28%), Spain (19.4% and 2.91%), or in Bulgaria (19.6% and 2.32%). On the contrary, the share of public final consumption expenditure in GDP was high in a group of countries where economic growth was weaker than the European average: in Sweden (respectively, 26.6% and 0.9%), Finland (26.4% and −0.1%), or in the Netherlands (25.1% and 0.63%).

Furthermore, in 2024, the adjusted wage share in labor costs represented 62.9% of the GDP on average in the European Union. However, in conformity with our hypothesis, we can note that increasing public spending could mainly be beneficial in countries where capitalization (share of capital in the production function) is weak. Indeed, the wage share in labor costs was higher in a group of countries where public gross fixed capital formation or final consumption expenditure was higher than the European average: in Slovenia (respectively, 74.3%, 5.2%, and 20.9%), Latvia (73.8%, 5.3%, and 22.5%), France (66.8%, 4.3%, and 24.3%), Croatia (66.1%, 5.7%, and 22.6%), or in Estonia (64.7%, 7.3%, and 21.1%). On the contrary, the wage share in labor costs and public gross fixed capital formation or final consumption expenditure were all weaker than the European average in Ireland (respectively, 36%, 2.5%, and 13%), Malta (50.3%, 4.1%, and 17.2%), Slovakia (54%, 3.7%, and 20.8%), or in Cyprus (56.5%, 2.9%, and 18.6%).

Moreover, in 2024, the average GDP growth rate was 1.12% in the European Union, whereas the implicit tax rate on consumption was 17.2%. However, in conformity with our hypothesis, we can note that economic growth was higher in a group of countries where consumption taxes were high. Indeed, implicit consumption taxes and economic growth were both higher than the European average in Denmark (respectively, 23.4% and 1.94%), Hungary (22.9% and 1.48%), Croatia (21.3% and 3.4%), Greece (20.2% and 2.28%), Slovenia (19.6% and 1.5%), Bulgaria (19% and 2.32%), Poland (18% and 2.96%), Lithuania (17.6% and 2.43%), Cyprus (17.4% and 3.29%) or in Malta (17.3% and 5%). On the contrary, implicit consumption taxes and economic growth were both weaker than the European average in Germany (respectively, 16.0% and 0.01%) or in Italy (16% and 0.67%).