1. Introduction

Globalization is vital for economic growth as it integrates different economies, cultures, technologies, and governance, creating interdependence across countries. This promotes the diffusion of technology, innovation, and efficient allocation of resources. Studies by

Madanizadeh and Pilvar (

2019),

Rashidi (

2022),

Gozgor (

2017), and

Nwosa et al. (

2020) consistently showed that increased trade openness reduces unemployment and boosts labor participation across various countries.

Hazera-Tun-Nessa et al. (

2021) and

Al-Taie et al. (

2023) found that trade openness increases unemployment.

Pal and Villanthenkodath (

2024) found that economic globalization increases long-term unemployment in low-income countries but promotes job creation and reduces unemployment in high- and middle-income countries from 1991 to 2020.

This study examines the hypothesis that rich countries with high economic growth and strong economic globalization can reduce unemployment by creating more job opportunities through increased labor demand, attracting foreign investment, and utilizing immigration to fill labor shortages. In these countries, economic growth typically drives the expansion of industries and services, which requires a larger workforce. As companies grow, they need more employees, reducing their unemployment rates. Additionally, globalization allows these countries to access larger international markets, increase trade and business opportunities, and stimulate job creation. This study examines several research questions. Does economic globalization affect the unemployment rate? Is there a spillover effect in other countries? Does the interaction between economic globalization and economic development or gross national income (GNI) per capita affect the unemployment rate? This question evaluates the impact of the interaction effect between economic globalization and GNI per capita on unemployment rates using extensive datasets for 158 countries covering 29 years from 1991 to 2019.

The impact of the interaction effect between economic globalization and GNI per capita on unemployment reflects how the relationship between economic globalization and unemployment varies depending on a country’s level of economic development. Specifically, it shows whether the effects of economic globalization on unemployment rates are stronger, weaker, or different in countries with high GNI per capita than in those with lower GNI per capita. In rich (high-GNI) countries, economic globalization may lead to lower unemployment rates because these countries typically have more robust economies, advanced infrastructure, and well-developed labor markets. These countries are better positioned to capitalize on the benefits of economic globalization, such as increased trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), and technological advances. They can adjust to shifts in global demand, diversify their industries, and retrain workers who may be displaced by global competition. In poor (low-GNI) countries, the interaction effect may indicate that economic globalization has a more negative or weaker effect on unemployment. These countries often face greater challenges in managing the disruptive impacts of economic globalization. For example, poor nations may experience higher unemployment as industries struggle to compete globally, and labor markets may not be equipped to handle the changes brought about by economic globalization. Additionally, these countries may lack the necessary social safety nets or institutional capacity to cushion the negative effects of economic globalization, resulting in more job losses.

In essence, the interaction effect helps explain why the consequences of economic globalization on unemployment are not uniform across all nations. This underscores how economic development, as measured by GNI per capita, influences a country’s ability to benefit from economic globalization and manage its potential disruptions to the labor market. Countries with a higher GNI per capita may experience more favorable outcomes from economic globalization, while those with a lower GNI per capita may face more significant challenges, potentially leading to higher unemployment.

Economic globalization can affect unemployment rates through various mechanisms, including trade liberalization, outsourcing, and foreign direct investment (FDI). As countries engage in global trade, industries facing international competition may experience job losses, while those benefiting from global markets may experience employment growth. Outsourcing and offshoring can also lead to job displacement in high-cost countries, whereas FDI can create jobs in host nations, although it may increase wage disparities. Economic globalization can have spillover effects, with economic shifts in one country influencing others, particularly through disruptions in global supply chains. The relationship between economic development (GNI per capita) and economic globalization further complicates the picture of unemployment. Wealthier countries, with higher GNI per capita, tend to experience more economic globalization but may cushion its negative effects with stronger social safety nets and labor market policies, while less-developed countries may be more vulnerable to global economic pressures. Empirical analysis using extensive datasets for 158 countries over 29 years (1991–2019) could explore these dynamics by examining how trade openness, FDI, and other globalization measures correlate with unemployment, factoring in the moderating effects of GNI per capita and local policies. Statistical techniques such as spatial econometrics can be used to assess globalization’s direct and spillover effects on unemployment across different nations.

Immigration is critical in supporting labor markets in wealthy countries by helping address skill gaps and labor shortages. Immigrants often take jobs in sectors with fewer local workers, ranging from low-skilled labor in agriculture and construction to highly skilled positions in technology and healthcare. By attracting skilled labor from abroad, these countries can maintain a dynamic workforce, which helps to keep unemployment rates low. However, the extent of this effect depends on factors such as government immigration policies, economic inclusion, and how well the labor force is equipped with the necessary skills to meet evolving market demands.

The relationship between economic globalization and gross national income (GNI) per capita is multifaceted and varies across countries. The interaction effect of economic globalization and GNI per capita shows that rich countries have high economic growth, as represented by a higher GNI per capita and high economic globalization. In comparison, poor countries have low economic growth, represented by a lower GNI per capita and lower economic globalization. While many high-income nations exhibit significant economic globalization and a high GNI per capita, the dynamics in low-income countries are more complex.

In wealthier nations, economic globalization often correlates with a higher GNI per capita, as these countries typically have robust institutions, advanced infrastructure, and a skilled workforce that enables them to capitalize on global trade and investment opportunities. In contrast, the relationship between economic globalization and GNI per capita in low-income countries is more complex. While globalization can provide access to new markets and technologies, it can expose these countries to economic volatility and increased competition.

Globalization generally promotes economic growth and efficiency through international cooperation, and its effects can vary greatly depending on a country’s level of economic development. The gross national income (GNI) per capita measures a country’s overall economic development, reflecting the average income of its citizens. While many studies have independently focused on trade openness or globalization, this study emphasizes the interaction between globalization and the GNI per capita. A Kuznets-like curve for unemployment suggests that in the early stages of economic development, unemployment may rise due to sectoral shifts, but as economies mature and diversify, unemployment decreases with improved job opportunities and workforce adaptation. It aims to understand how economic development, as measured by GNI per capita, influences and modifies the effects of globalization on unemployment.

This study identifies and quantifies how per capita GNI mediates the relationship between globalization and unemployment. This suggests that in countries with higher GNI per capita, globalization might lead to more positive outcomes (lower unemployment), whereas in countries with lower GNI per capita, the effects could be more mixed or even negative. This interaction is crucial for policymaking, implying that a one-size-fits-all approach to managing globalization’s impacts might not be effective.

The interaction between GNI per capita and globalization on unemployment can be understood through intuitive observations and theoretical frameworks. While rising GNI per capita is generally associated with economic growth and job creation, globalization introduces complexities that can create and displace jobs, leading to nuanced effects on unemployment. Understanding these dynamics is essential for formulating effective economic policies to promote sustainable employment growth in a globalized economy.

The spatial approach enhances our understanding of the impact of globalization on unemployment by examining how various factors influence labor dynamics. It allows for identifying geographical patterns and disparities in unemployment rates, providing insights into how different areas are affected by global economic forces.

1.1. Intuitive Reasoning

A higher GNI per capita indicates a prosperous economy that often leads to job creation. As GNI increases, businesses may expand, invest in new technologies and capital-intensive industries, and increase their workforce, thereby reducing unemployment. Capital-intensive industries often involve complex production processes that require significant investment in technology and machinery. Capital-abundant countries (e.g., the United States) tend to specialize in and export capital-intensive goods because they have more capital than labor. Consequently, these industries tend to yield higher productivity per worker and sustain higher wages. This access can help local businesses to grow and hire more employees.

Conversely, in the context of lower GNI, economic growth may be sluggish, leading to higher unemployment rates. Globalization allows countries to access larger markets and facilitate trade and investment. Labor-intensive industries are typically more straightforward and rely on manual labor, which can lead to lower productivity per worker but higher employment levels. Labor-abundant countries (e.g., Bangladesh) specialize in and export labor-intensive goods because of their larger labor force than capital.

The lack of globalization restricts market opportunities and job creation. Globalization has shifted economies from traditional to competitive sectors, creating new jobs but displacing workers in declining industries and causing short-term unemployment. Increased competition improves efficiency and lowers prices but may lead to firm closures and short-term unemployment.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

Trade theories on economic development and growth explain how international trade influences a country’s economic prosperity, growth trajectory, and overall development. These theories examine how exchanging goods, services, capital, and labor across borders impacts various aspects of an economy, such as production, income distribution, technological advancement, and resource allocation. The overarching purpose of these theories is to help understand the conditions under which trade fosters economic development and how different nations can benefit from global trade depending on their economic structures and policies.

Several economic theories support the interaction between globalization and GNI per capita concerning unemployment, and the Kuznets hypothesis suggests that income inequality first increases and then decreases as an economy develops. During the early stages of globalization and economic development (when GNI per capita is low), workers in traditional sectors may lose jobs as industries modernize. As the economy grows (higher GNI), new job opportunities in modern sectors may decrease unemployment.

The Heckscher–Ohlin model suggests that countries export goods by using abundant production factors. As a country globalizes and increases its GNI per capita, it may specialize in industries with comparative advantages. This specialization can create new job opportunities while displacing jobs in less competitive sectors, leading to complex interactions with unemployment rates. As GNI per capita rises, education and skill development become more critical, potentially reducing unemployment for skilled workers and increasing it for unskilled workers, thus highlighting the interaction effect.

By examining the interaction between GNI per capita and economic globalization, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how economic development levels shape a country’s ability to harness or mitigate the effects of globalization, particularly in terms of labor markets and employment outcomes. This insight could help policymakers tailor strategies better suited to their countries’ economic contexts, ensuring that globalization benefits a broader segment of society and mitigates the risks associated with economic integration.

The globalization index includes political, social, and economic dimensions, with higher values indicating greater globalization. Economic globalization has two dimensions: trade, capital restrictions, and actual economic flows. The sub-indexes for actual economic flows include portfolio investment data, foreign direct investment (FDI), and trade. The sub-index for capital restrictions considers taxes on international trade, hidden import barriers, the index of capital controls, and mean tariff rates (

Haelg, 2019;

Gygli et al., 2019).

1.3. Spillover Effects of Economic Globalization

We examine the impact of economic globalization on unemployment rates within a spatial framework. This study also assesses the impact of economic globalization and the interaction effect of economic globalization and GNI per capita on unemployment rates. This study employs alternative spatial weighting measures, such as the cultural, linguistic, and historical relations of countries and their trade pacts, in addition to the neighborhood.

This research is supported by various trade theories, such as Classical Trade Theories, including comparative advantage (Ricardo) and factor proportions (Heckscher–Ohlin), to explain how GNI per capita influences trade patterns.

Krugman (

1979,

1980) emphasizes economies of scale and product differentiation, particularly how globalization interacts with income levels to affect trade dynamics. This suggests that trade can arise from firms seeking economies of scale, leading to specialization and intra-industry trade among similar countries. This theory emphasizes the role of market structures, consumer preferences, and globalization in shaping trade patterns, fostering competition, and driving innovation. The Endogenous Growth Theory considers how human capital and globalization can lead to technological advancements and increased GNI per capita through trade. With the support of multiple theories, this study provides a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interactions between economic development (GNI per capita), economic globalization, and unemployment outcomes.

Our analysis includes several control variables to better explain the factors influencing unemployment. These variables include GDP, which reflects a country’s overall economic activity and ability to generate jobs. We also account for inflation, as changes in price levels can impact wage growth, hiring practices, and population, which influence labor supply and potential unemployment levels. Additionally, female workforce participation is considered, reflecting gender dynamics in the labor market, and net migration is included to capture the effects of labor movement on employment opportunities. These control variables provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing unemployment.

This study makes several significant contributions to the literature by analyzing the spillover effects of economic globalization on unemployment using the spatial Durbin model (SDM), which accounts for spatial interdependencies between countries. It also explores the interaction between economic globalization and GNI per capita in influencing unemployment rates, offering insights into how trade openness and economic development jointly impact unemployment. A key innovation of this study is the construction of a novel weight matrix that considers countries with similar cultural, political, social, linguistic, and historical backgrounds, trade pacts, and neighborhood ties. This approach provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding economic interdependencies than traditional models, which primarily focus on geographical or economic proximity. By incorporating these factors, this study addresses the gaps in previous non-spatial research and highlights the complex, multidimensional nature of the relationship between economic globalization and GNI per capita on unemployment.

This study analyzes the spillover effect of economic globalization on the unemployment rate using the spatial Durbin model (SDM). This study also investigates the interaction impact of economic globalization and GNI per capita on unemployment rates. This interaction effect indicates how economic development and trade theories explain the effects of trade openness on the unemployment rate. This study incorporates a new weight matrix constructed for countries with similar cultural, political, social, language, and historical backgrounds and trade pacts (CPSLHT) as well as neighborhoods, making the study unique and novel. Most previous studies were non-spatial; therefore, spillover effects were not analyzed.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The

Section 2 presents a brief review of the literature on this topic.

Section 3 presents the data set, empirical model, and econometric methods used in the analysis. The

Section 4 presents statistical evidence on the interaction effect of GNI per capita and EGLOBI (or GNI per capita and FDI or TRADE Openness) on unemployment rates and the results of spatial panel statistical methods. The

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Recent developments in spatial literature have expanded the understanding of spatial econometrics, with numerous studies delving into various aspects of contemporary spatial research. Although these studies examine a wide range of topics, they often do not directly address the impact of economic globalization on unemployment.

Mahmood (

2023) used the spatial Durbin model to analyze the effects of foreign direct investment (FDI), exports, and imports of emissions in Latin America from 1970 to 2019.

The effect of globalization on unemployment remains complex, and its impact differs across countries and regions. Trade theories, such as Ricardo’s concept of comparative advantage, argue that specialization and efficient resource use can reduce unemployment, benefiting countries with natural advantages. However, countries lacking such advantages may not experience similar reductions in unemployment (

Altiner et al., 2018). In contrast,

Helpman et al. (

2010) suggested that globalization leads to lower unemployment, a view also supported by

Janiak (

2007).

On the other hand,

Mitra and Ranjan (

2010) found a negative relationship between globalization and unemployment. However,

Moore and Ranjan (

2005) and

Sener (

2001) could not establish a consistent relationship between the two. A study by

Awad and Youssof (

2016) looked at how the Malaysian labor market responded to globalization between 1980 and 2014. Using the autoregressive distributed lag method, they found that economic globalization significantly reduced unemployment in Malaysia.

Gozgor (

2017) extended the analysis to 85 countries from 1991 to 2014 and concluded that globalization tends to reduce the structural unemployment rate. Similarly,

Altiner et al. (

2018) studied 16 emerging market economies from 1991 to 2014, finding mixed results. Globalization was linked to higher unemployment rates in Colombia, Hungary, India, Malaysia, Poland, South Africa, and Turkey. However, it reduced unemployment in countries like China, Indonesia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, and Russia.

The relationship between globalization and youth unemployment was also explored in a study covering 50 African countries from 1994 to 2013 using the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM). The results indicated greater openness to global markets correlated with lower youth unemployment (

Awad, 2019). Similarly,

Carrère et al. (

2020) studied 107 countries from 1995 to 2009, incorporating sector-specific search-and-matching frictions into a Ricardian model. Their findings revealed that trade could increase unemployment in countries with comparative advantages in low-efficiency sectors, but trade reduced unemployment in countries with high-efficiency sectors.

Elhorst and Emili (

2022) examined 12 provinces in the Netherlands from 1974 to 2018 and observed that the degree to which spillover effects from neighboring countries and output multipliers are factored into economic analysis influences how economic growth can reduce unemployment.

Dutt et al. (

2009) showed that trade openness negatively correlates with unemployment, while protectionist policies have the opposite effect, leading to higher unemployment. Their robust results across various models lended weak support to the Heckscher–Ohlin theory regarding trade–unemployment relationships, suggesting that productivity effects dominate sectoral changes in countries rich in labor and capital.

Similar findings of unemployment-reducing effects of trade liberalization were identified by

Felbermayr et al. (

2008), where these effects were also attributed to productivity-driven forces. However,

Helpman and Itskhoki (

2007) warned that liberalizing trade could increase overall unemployment. Studies such as those by

Davidson et al. (

1999) and

Moore and Ranjan (

2005) provided mixed results, with no clear conclusion on the overall effect of trade on unemployment.

Al-Taie et al. (

2023) analyzed Iraq’s trade policy, which was isolated from other economic strategies due to its oil dependence and rigid production system. They found that Iraq’s limited diversification exacerbated unemployment. Similarly,

Hazera-Tun-Nessa et al. (

2021) showed that trade openness increased unemployment in 12 less-developed countries (LDCs) between 1995 and 2016.

Famode et al. (

2020) found that trade openness had only a weak long-term effect on unemployment in the Congo from 1991 to 2017, suggesting that other factors played a more significant role in determining unemployment.

Das and Ray (

2020) explored whether globalization influences employment generation in South Asian countries between 1991 and 2016. They found no long-term relationship for most countries except Bhutan, the Maldives, and Nepal. Their panel analysis indicated that while globalization affects short-term employment, the long-term impact varies across countries. Similarly, a study by

Ali et al. (

2021) assessed the relationship between trade openness, human capital, public expenditure, institutional performance, and unemployment in Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) countries. Their long-term estimates revealed that trade openness has a negative and significant relationship with unemployment in lower-income OIC economies, while it correlates positively with unemployment in higher-income OIC countries. This highlights the varying effects of globalization depending on the country’s income level.

Most previous studies have primarily focused on examining the impact of globalization on unemployment using non-spatial econometric methods, which often overlook the geographical context and spatial dependencies. This study aims to address this gap by incorporating spatial analysis, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of how different factors, including trade policies and labor market conditions, influence unemployment across various regions. Accounting for spatial dependencies can provide insights into how neighboring countries or regions may influence one another’s unemployment trends. Using the spatial Durbin model (SDM), the study considers not only the direct impact of globalization on unemployment in a specific region but also how neighboring regions may be influenced (spillover effects). Additionally, this study investigates how the level of gross national income (GNI) per capita interacts with the effects of economic globalization on unemployment. This part of the analysis explores whether the relationship between globalization and unemployment differs depending on the economic strength of a region, as measured by its GNI per capita. The goal is to understand better how these factors shape unemployment dynamics across different regions and economies.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model Specification

The data of clustered units based on neighborhood or trade pacts and social, political, cultural, or historical reasons are not independent and are spatially correlated. A wide range of spatial panel models has been estimated. According to

Elhorst (

2014), three types of interaction effects can be estimated: endogenous interaction effects among dependent variables (Y), exogenous interaction effects among independent variables (X), and interaction effects among error terms (ε).

The SDM (spatial Durbin model) generalizes the spatial autoregressive (SAR) model and implies global spatial spillovers. The explanatory variables of this model include spatially weighted independent variables. The SDM incorporates both endogenous and exogenous interaction effects. The endogenous effects of this model capture how the value of the dependent variable U for a spatial unit may also be affected by the dependent variables of other spatial units. The exogenous effect captures how the value of the dependent variable U for a spatial unit may also be affected by independent variables of other spatial units. The spatial dependence of unemployment in one country on unemployment in others and economic globalization in other countries is estimated using SDM.

The economic globalization–unemployment nexus has been revisited by applying spatial panel econometric methods using SDM. SDM provides estimates of explanatory variables in a particular plot, state, and country as well as in neighboring plots, states, and countries (

Guo & Marchand, 2019). This must be considered when using the spatial correlation approach because the actual space, border, or neighborhood does not usually present strong correlations. However, strong correlations could exist between different patterns, such as a group of countries in a trade pact, everyday language, or historical reasons. Different approaches can be considered to determine the weighted spatial matrix W based on different causes of the correlations.

The SDM incorporates both endogenous and exogenous interaction effects. The SDM includes the spatial lags of both the dependent and independent variables on the right-hand side of the model, thus capturing the properties of both spatial lag and errors (

Thang et al., 2016). SDM is the most appropriate model if there are spatially correlated omitted variables that correlate with an explanatory variable (

LeSage & Pace, 2009). The spatial dependence of unemployment in a country on unemployment in others and economic globalization in other countries was estimated using SDM. The basic equation for this model is as follows (

Belotti et al., 2017;

Elhorst, 2014;

LeSage, 1999).

The dependent variable

denotes the n × 1 column vector of the dependent variable;

denotes the n × k matrix of regressors, where t = 1, …; T indicates time series periods;

denotes the n × k matrix of regressors used for the interaction effect between spatial weights and regressors;

is the regression coefficient;

is the spatial autoregressive parameter reflecting the strength of the spatial dependencies; and

is the unobserved error term. W is an n × n matrix, indicating the spatial arrangement of n units. Each entry

W represents the spatial weight associated with units i and j, where i is the ith country and j is the related country. Self-neighbors are excluded by conventionally setting the diagonal elements

equal to zero (

Belotti et al., 2017). The variables used in this study are presented in

Table 1.

The expanded form of Equation (1) using economic globalization is as follows:

Instead of EGLOBI, we used FDI and trade OPENESS in the decomposed components of economic globalization. Similarly, instead of GNI_EGLOBI, we used GNI_FDI and GNI_OPEN.

The SAR (spatial autoregressive) model is specified as follows.

The SAC (SAR with spatially autocorrelated errors) can be specified as below:

M is a spatial weight matrix that may or may not equal W.

The following equation estimates the spatial error model (SEM): SEM focuses on SAC in the error term.

The expanded form of Equation (6) is as follows:

The estimation of the spatial model is sensitive to the format of the weight matrix W. W is the row-standardized spatial weight matrix, whose elements are defined as follows (

Pisati, 2001):

We constructed an alternative weight matrix (CPSLHT) for a group of countries in geographical locations with similar cultural, political, social, linguistic, and historical backgrounds, such as South Asia, East Asia, ASEAN, Central Asia, the Middle East, Oceania, East Europe, West Europe, Africa, South America, and North America and trade pacts. We use this weight pattern for the pre-2000 trade agreements. The second weight matrix was constructed based on geographical distance or neighborhood.

The following trade pacts were included in the weight matrix: Central American Integration System, Central European Free Trade Agreement, Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, Council of Arab Economic Unity, Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement, United States and Central American Countries, East African Community, Economic Cooperation Organization Trade Agreement, European Economic Area, European Free Trade Association, European Union Customs Union, G3 Free Trade Agreement, Gulf Cooperation Council, Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation, South Asian Free Trade Area, Southern African Development Community, Southern Common Market, North American Free Trade Agreement, Arab Cooperation Council, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, Black Sea Economic Cooperation Zone, and Caribbean Community and Common Market.

We specified and estimated spatial econometric models to empirically verify spatial externalities and measure their strengths and ranges (

Anselin, 2003). Spatial models require a spatial weight matrix (SWM) that shows the spatial relationships among variables in a dataset. A spatial weight matrix member would take a value of “1” if i and j are neighbors or related countries or “0” otherwise. In this study, W is a 158 × 158 matrix. The spatial panel regression model was estimated by conceptualizing the spatial relationships of polygon root contiguity. The SDM marginal effects were estimated for the spatial and time-fixed effects of unemployment rates. A quasi-maximum likelihood estimation method was used.

3.2. Data

The data for this study were obtained from the World Development Indicators of the

World Bank (

2020a). The dependent variable was the unemployment rate data collected from

ILO (

2020). Spatial model estimation was performed using the techniques provided by STATA software (version 18).

Table 1 lists the variable names and definitions used in this analysis. All regressions were run with the first differences, and all variables were converted into natural logarithms. Two sets of regressions were estimated: one included economic globalization as an explanatory variable, while the second incorporated economic globalization components, namely FDI and trade openness, as explanatory variables.

Understanding the spatial dynamics between unemployment and economic globalization poses a significant challenge largely because of the intricate nature of economic globalization. This concept encompasses diverse policies and phenomena that complicate the identification of its precise effects on unemployment at different spatial scales. To address this complexity, it is essential to deconstruct economic globalization into its individual components, such as the deregulation of capital flows and shifts in trade policies. Researchers can more effectively analyze spatial implications and formulate targeted policy responses by elucidating the specific channels through which each component influences unemployment. For example, the impacts of deregulating capital flows may manifest differently spatially, potentially leading to increased financial volatility and speculative behavior.

Conversely, changes in trade policies can directly affect the competitiveness of local industries and labor markets, resulting in distinct spatial consequences for unemployment. By dissecting these components separately, researchers can discern variations in their effects across countries or sectors, providing valuable insights for policymakers striving to navigate the complexities of economic globalization while mitigating its adverse impacts on unemployment. In summary, disaggregating economic globalization into its constituent parts, such as foreign direct investment and international trade openness, offers a systematic approach to enhancing the analytical rigor and practical relevance of research on the spatial dimensions of unemployment within the context of globalization.

According to the World Bank, the definitions of labor force and unemployment rate can vary significantly between countries, leading to inconsistencies in data interpretation. This study used labor force and unemployment rate data from ILO to address this issue, as it provides internationally consistent definitions and measurements. This ensures comparability across countries and helps eliminate discrepancies caused by differing national definitions, allowing for a more accurate and standardized analysis of global unemployment trends.

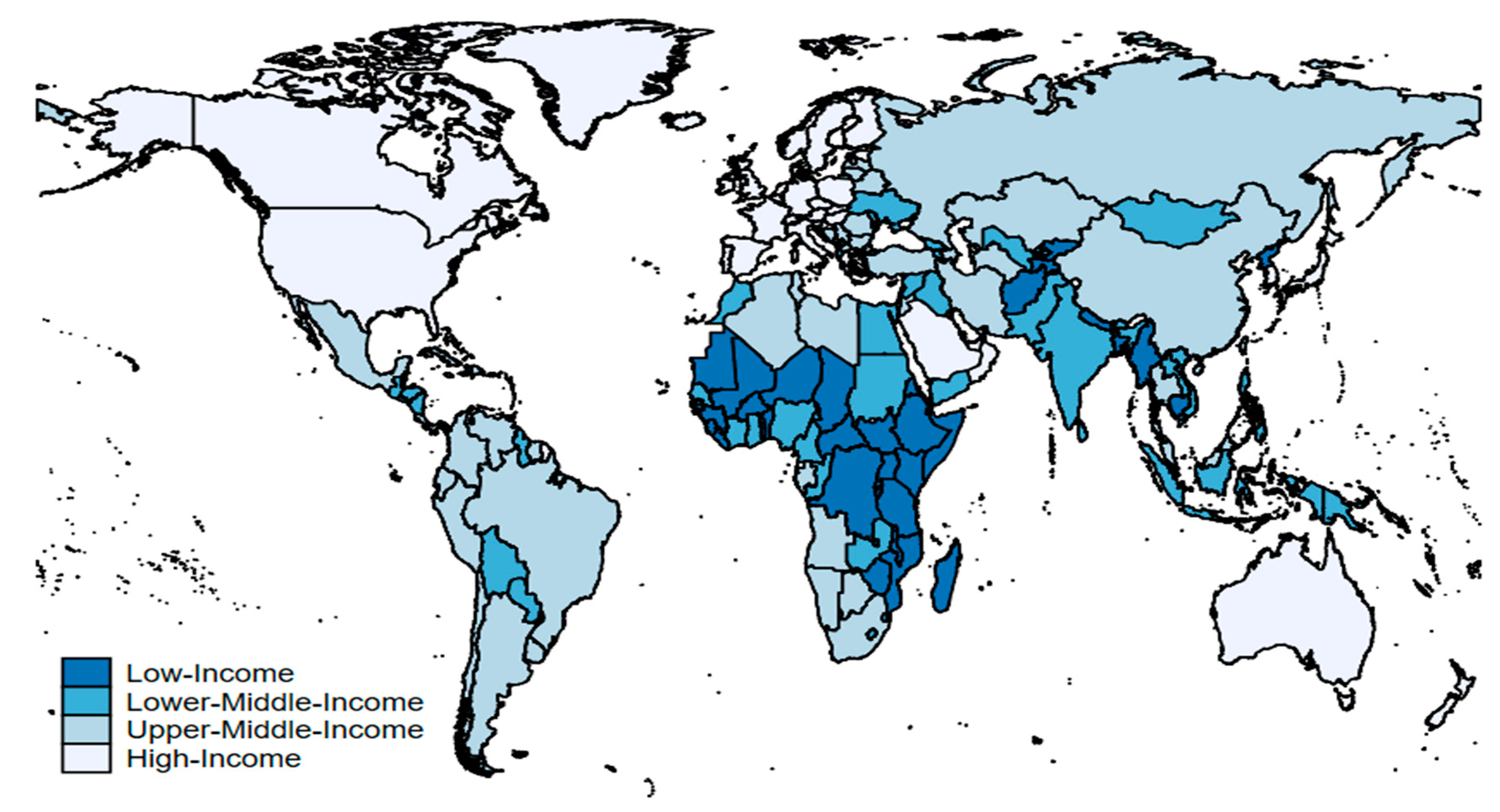

We analyzed four categories of countries classified by the World Bank (

World Bank, 2020b). Using the Atlas method, we classified 158 countries into four categories according to the World Bank’s classification of countries based on the current GNI per capita in USD (

World Bank, 2020a). The thresholds for income classification in 2019 are as follows: less than USD 1026 is a low-income country, USD 1026 to USD 3995 is a lower-middle-income country, USD 3996 to USD 12,375 is an upper-middle-income country, and higher than USD 12,375 is a high-income country.

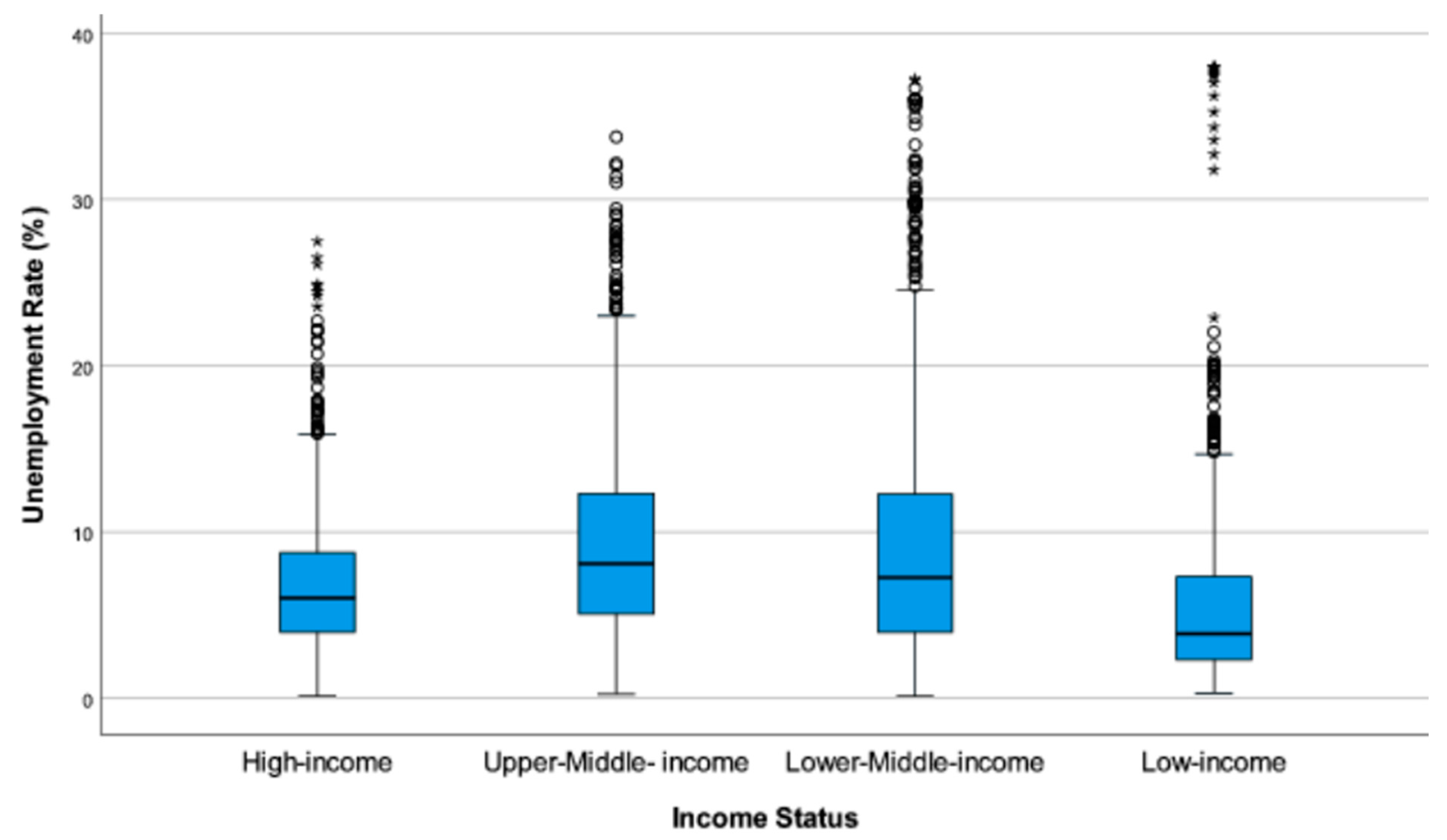

The average unemployment rate for the 158 countries from 1991–2019 was 7.6%. The average unemployment rate was 7.29% in high-income countries, 10.01% in upper-middle-income countries, 7.30% in lower-middle-income countries, and 4.24% in low-income countries (

Table 2).

Figure 1 illustrates the unemployment rate. The

Figure 1 clearly shows the outliers in the unemployment rates.

The average GDP per capita for the 158 countries during 1991–2019 was USD 17,549.59. The minimum GDP per capita was USD 436.72, with a maximum of USD 114,889.18 (

Table 3).

Figure 2 presents GDP per capita by income level.

Appendix A Table A1 provides a list of countries used in this study.

Initially, we examined the relationship between economic globalization and unemployment and found a significant endogeneity issue using the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test. To mitigate this, we substituted economic globalization with foreign direct investment (FDI) and international trade openness. Subsequent testing revealed no significant endogeneity with these alternative variables.

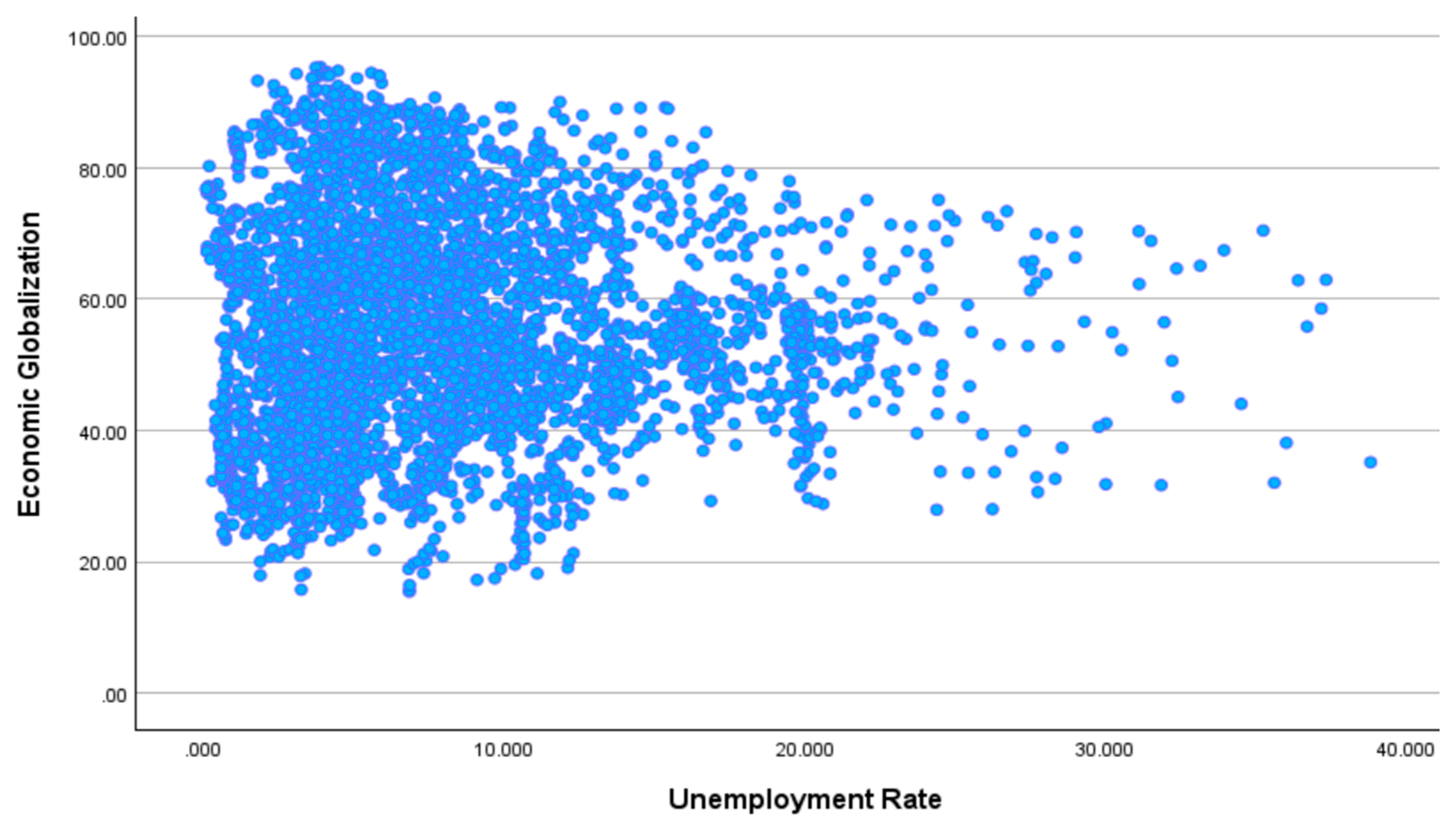

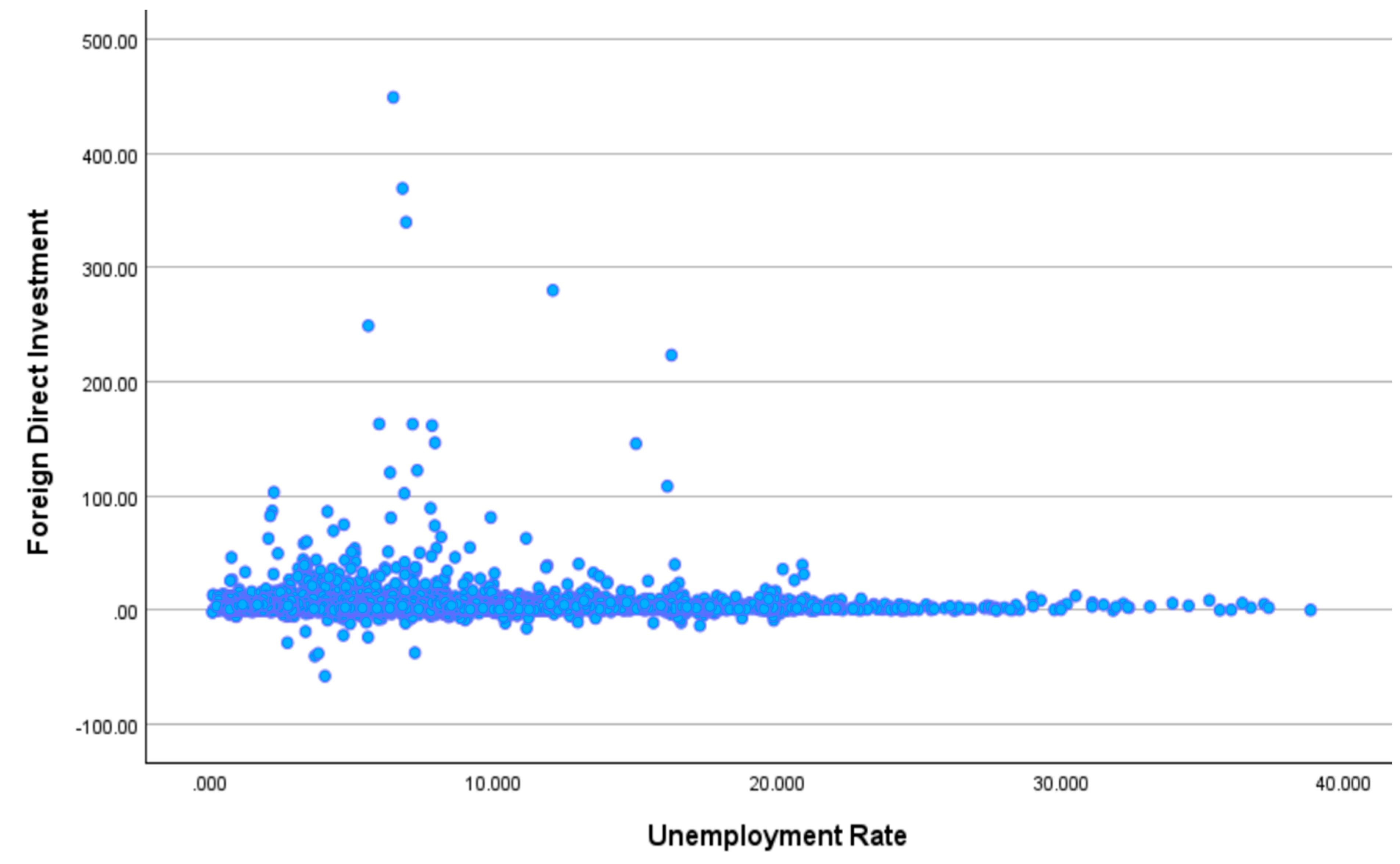

Scatter plots depicting the relationships between the unemployment rate and economic globalization (

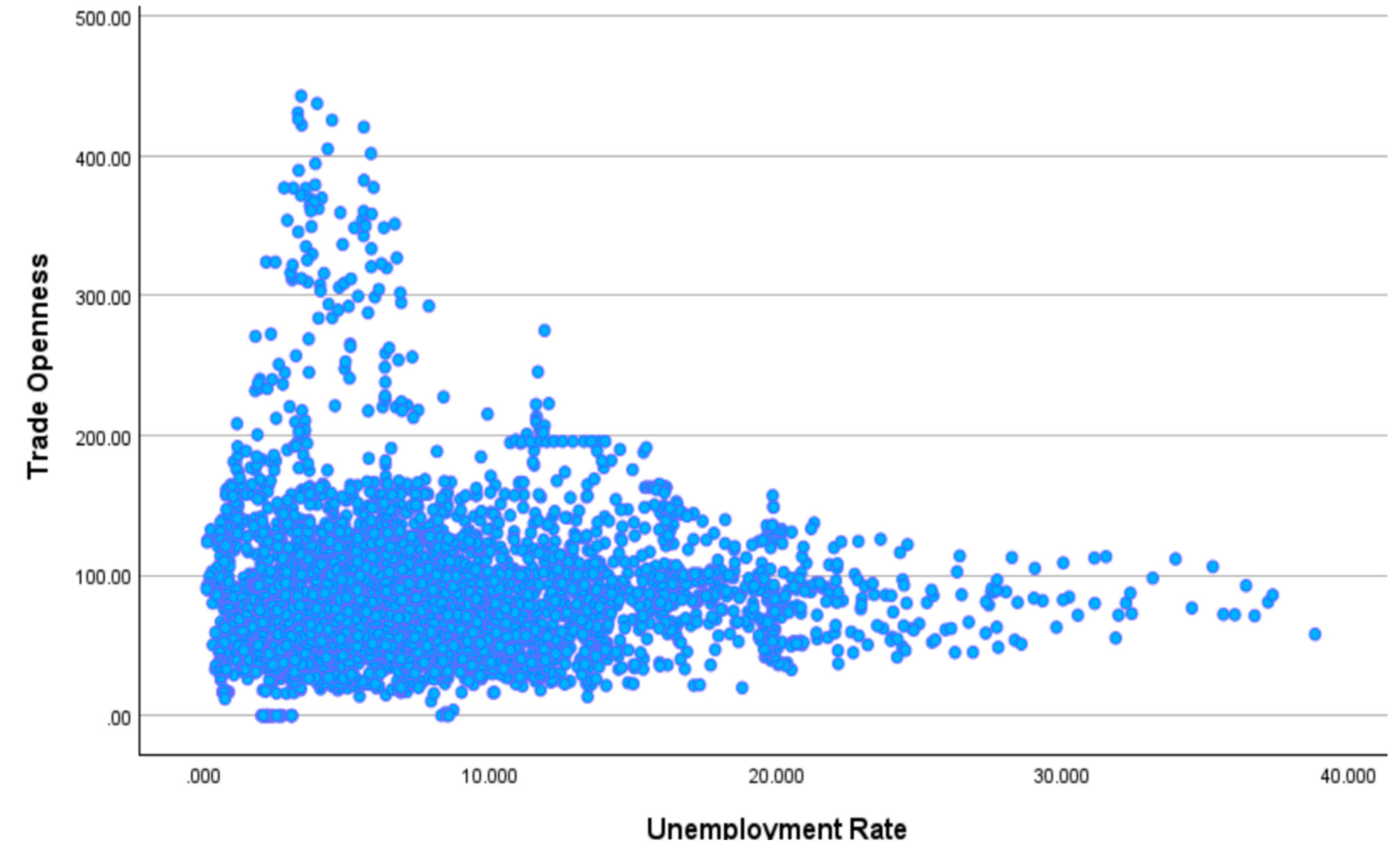

Figure 3) and between the unemployment rate and international trade openness (

Figure 4) show negative correlations. The unemployment rate and foreign direct investment (

Figure 5) lack strong correlations.

5. Discussion

This study examines the effect of the interaction between economic globalization and GNI per capita on unemployment rates in 158 countries from 1991 to 2019 using the spatial Durbin model (SDM). The estimates based on the CPSLHT weight matrix provided better results.

The estimates from SDM using economic globalization and its decomposed components showed that the direct and indirect effects of GDP on unemployment rates are negative and significant in the short and long run. The negative and significant effects of GDP on unemployment rates, both directly and indirectly, suggest that policymakers should prioritize strategies that promote sustained economic growth to reduce unemployment. This can be achieved through policies that support investment, innovation, and global economic integration. Given the spillover effects observed in the spatial Durbin model, coordinating regional and international policies is crucial for addressing potential disparities. Additionally, while globalization can help lower unemployment, it is important to implement policies that protect vulnerable sectors and ensure that the benefits of growth are widely distributed across all regions.

The direct effect of population growth on the unemployment rate was positive and significant in both the short and long terms in models that used both overall and decomposed economic globalization. The positive and significant direct effect of population growth on unemployment in both the short and long term suggests that policymakers must focus on creating a more flexible labor market, investing in sectors that generate jobs, and enhancing education and skill development to equip the growing labor force. Additionally, improving infrastructure in urban areas and ensuring balanced regional development are crucial to absorb the rising labor supply. Population control measures and immigration policies may also be needed to manage the growth rate, ensuring that economic opportunities keep pace with the increasing population and prevent high unemployment.

The indirect coefficient of the female labor force participation rate was negative and significant in both the short and long run in models with both overall and decomposed economic globalization. The negative and significant indirect effect of female labor force participation (FLFP) on unemployment suggests that increasing women’s workforce participation can have broad positive spillover effects on reducing unemployment regionally and over time. Policymakers should prioritize initiatives that support female employment, such as improving access to affordable childcare, promoting flexible work arrangements, and addressing gender disparities in wages and job opportunities. Additionally, fostering women’s participation in globally integrated sectors through education and skills training will further enhance these benefits and contribute to national and regional unemployment reduction.

In the economic globalization model, the direct effect of net migration on unemployment was negative but insignificant. However, in the model with decomposed economic globalization, the direct effect of net migration was negative and significant in both the short and long term. The findings suggest that net migration may not significantly impact unemployment in a broad economic globalization context when specific aspects of globalization are considered (e.g., trade openness or foreign direct investment); net migration has a more pronounced and beneficial effect, reducing unemployment. This implies that policymakers should focus on migration policies that align with the key aspects of globalization, such as attracting skilled migrants to globally integrated or export-oriented industries, which can contribute to lowering unemployment. Additionally, fostering conditions that enhance the positive effects of migration on labor markets, such as improving integration and labor market access for migrants, can further amplify these benefits.

The direct and indirect coefficients of inflation were negative and significant in the short and long run in the economic globalization model. In the model with decomposed economic globalization, the direct effect of inflation remained negative and significant in both the short and long term. The negative and significant direct and indirect effects of inflation on unemployment in both the short and long run, particularly in the context of economic globalization, suggest that moderate inflation can help reduce unemployment by stimulating demand and production. Policymakers should aim to maintain inflation at manageable levels through sound monetary policy while capitalizing on the positive interactions between inflation and specific aspects of globalization, such as trade openness and capital mobility, to enhance employment opportunities. However, they should remain cautious about excessively high inflation, which could destabilize the economy and undermine employment benefits.

In the economic globalization model, the indirect effect of economic globalization on the unemployment rate was negative and significant in both the short and the long run. In the model with decomposed economic globalization, the short- and long-term coefficients of FDI were negative but not significant, while the indirect effect of trade openness was negative and significant at the 5% level in both the short and long term. The negative and significant indirect effect of trade openness on unemployment suggests that policies promoting trade openness can play a crucial role in reducing unemployment in both the short and long term. Policymakers should focus on reducing trade barriers, fostering international trade agreements, and strengthening global supply chains to maximize the positive spillover effects of trade on employment. Although the impact of FDI on unemployment was nonsignificant, efforts to attract FDI to sectors with higher job creation potential could complement trade policies and contribute to long-term employment growth. This study aligns with

Pal and Villanthenkodath’s (

2024) findings that economic globalization fosters job creation in high- and middle-income countries, resulting in a long-term decrease in unemployment.

Rodrik (

2012) advocated for “smart globalization,” emphasizing the balance between government regulation and market freedom. He warned that excessive government control leads to protectionism, whereas unchecked markets cause instability and inequality. Rodrik called for a managed form of globalization, where governments ensure that global integration benefits society without creating economic volatility.

Joseph E. Stiglitz’s (

2003) Globalization and Its Discontents critiques the negative effects of globalization, highlighting how institutions such as the IMF and World Bank often harm poorer nations. He argued that globalization increases inequality and instability, benefiting corporations more than people, and called for reforms to make globalization more inclusive. Globalization and Growth in the Twentieth Century by

Nicholas Crafts (

2000) examines how globalization influenced economic growth throughout the 1900s. Crafts highlighted that globalization drove growth, but its benefits were uneven, with some countries advancing while others fell behind. He stressed the need to understand the complex relationship between globalization and growth to create effective policies.

Globalization and Its Impact on Economic Development by

Grzegorz W. Kołodko (

2006) explores how globalization can drive economic progress, particularly for developing nations, by improving access to markets, technology, and capital. However, Kolodko also warned that globalization can exacerbate inequality and instability if not managed well. He advocated for policies that ensure the benefits of globalization are more widely shared and contribute to sustainable development.

The direct interaction effect of GNI per capita and economic globalization on the unemployment rate was negative and statistically significant in the model with economic globalization. In the model with decomposed economic globalization, the direct interaction effect of GNI per capita and FDI was negative and significant in both the short and long terms. In contrast, the interaction effect of GNI per capita and trade openness was negative and significant in both time frames. The negative and significant interaction effect between GNI per capita and economic globalization, particularly through trade openness and FDI, suggests that as countries grow wealthier, the benefits of globalization in reducing unemployment are enhanced. Policymakers should prioritize strategies that simultaneously boost domestic income levels, such as productivity improvements and investment in education, while actively promoting trade openness and attracting foreign direct investment. This combined approach can maximize the employment-reducing effects of globalization, ensuring that higher-income nations leverage their economic strength to benefit from global integration and reduce unemployment more effectively.

The coefficients of lagged unemployment rates on unemployment rates were positive and significant in both the models with economic globalization and the model with decomposed economic globalization. The positive and significant impact of lagged unemployment rates on current unemployment suggests that unemployment tends to persist over time, making it more difficult to reduce once it increases. Policymakers should focus on early intervention and sustained efforts to address unemployment, including job creation initiatives, labor market reforms, and retraining programs that equip workers with new skills. In the context of economic globalization, enhancing trade competitiveness and attracting investment can further aid in reducing unemployment persistence. Policymakers can prevent short-term unemployment from becoming a long-term structural issue by adopting swift and proactive measures.

An endogenous spatial effect was evident in the spatial lag of the dependent variable (ρ), where the spatially lagged unemployment coefficient (Rho, ρ) indicates significant spillover effects on local unemployment rates from neighboring countries. This was observed in both models with economic globalization and decomposed economic globalization using the CPSLHT weight matrix. The significant spillover effects of unemployment from neighboring countries, as indicated by the spatially lagged unemployment coefficient (Rho, ρ), suggest that unemployment is a domestic issue and is influenced by regional economic conditions. This underscores the need for regional cooperation and policy coordination to address unemployment. Policymakers should collaborate with neighboring countries on harmonized labor market policies, trade agreements, and economic strategies to effectively manage unemployment. Participation in regional economic unions or organizations can help mitigate cross-border spillover effects, ensuring that unemployment reduction strategies are more comprehensive and regionally integrated. Managing population growth, stimulating GDP growth, allowing moderate inflation, increasing female participation in the workforce, and implementing well-structured migration policies are crucial for reducing unemployment rates. These strategies work together to create a balanced economic environment that supports job creation, ensures workforce diversity, addresses demographic challenges, and promotes long-term employment.

Theoretically, economic globalization with the interaction of GNI per capita, driven by comparative advantage, factor proportions, economies of scale, and product differentiation, has spurred growth in wealthy nations. These principles enable countries to specialize in areas where they are most efficient, leading to increased productivity and economic expansion. Regarding immigration, research indicates that allowing labor mobility can significantly reduce unemployment.

Clemens and Pritchett (

2016) argued that permitting people to move from low-productivity places to high-productivity places is one of the most efficient tools for reducing poverty and unemployment. Their study argued that while immigration can offer benefits in filling labor shortages and supporting economic growth, restrictions may lead to tighter labor markets in specific industries or regions, potentially driving unemployment.

The practical implications of this study are as follows: Rich countries with high economic growth and strong economic globalization have the unique advantage of reducing global unemployment through immigration. As these economies expand, they create a greater demand for labor, which immigrants can help meet by filling gaps in various sectors, including technology, manufacturing, and services. Additionally, immigrants often possess valuable skills that boost innovation and productivity, contributing to further economic growth. Globalization enables these countries to integrate into global markets, attract skilled workers worldwide, and address labor shortages. Immigration helps to maintain a dynamic workforce, which is crucial for sustaining social services, supporting aging populations, and reducing unemployment rates.

By contrast, poorer countries with low economic growth, limited globalization, and high population growth face significant challenges. Their economies often cannot create enough jobs to absorb the expanding labor force, leading to higher unemployment rates and underemployment. These countries lack the infrastructure, investment, and industrialization to support large-scale job creation. While immigration is less common in these regions, many individuals from poorer countries seek better opportunities abroad, contributing to a “brain drain” that further stunts economic development. Without sufficient resources or opportunities, these nations struggle to provide sustainable employment to their growing populations, exacerbating economic inequality.