Religious-Based Family Management and Its Impact on Consumption Patterns and Poverty: A Human Resource and Management Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Hypothesis Development

2. Methodology

2.1. Sample Criteria

2.2. Variable Measurement

- Religious-based family management (RBFM):This variable was measured using positively framed statements. Higher scores (1 = strongly agree) indicated stronger adherence to religious values, which were hypothesized to positively influence family welfare. Six indicators were initially included: effort in prayer, awareness of divine observation, adherence to religious rules, belief in divine power, patience for divine will, and consistent worship. However, RBFM6 (“We continuously pray and strive for a better life”) was removed due to conceptual redundancy with RBFM1 (“We always strive earnestly in prayer”), as identified during the pilot test (Carradus et al., 2020; Tamsah et al., 2023). The remaining five indicators adequately capture the core dimensions of RBFM, ensuring conceptual clarity and reliability.

- Short-term vision (STV), uncontrolled consumption (UC), and absolute poverty (AP):These variables were measured using negatively framed statements. Higher scores (5 = strongly agree) reflected worse economic conditions.

- ▪

- STV indicators include necessity-driven spending, lack of savings orientation, and limited financial planning (Tamsah et al., 2023).

- ▪

- UC indicators include unplanned consumption, debt-inducing purchases, and consumption driven by basic desires (Tamsah et al., 2023).

- ▪

- AP indicators are based on the Indonesian government’s poverty benchmarks, such as access to quality health services, adequate housing, and sustainable natural resources (Tamsah et al., 2023).

3. Results

3.1. Normality Test

3.2. Statistical Results

- ▪

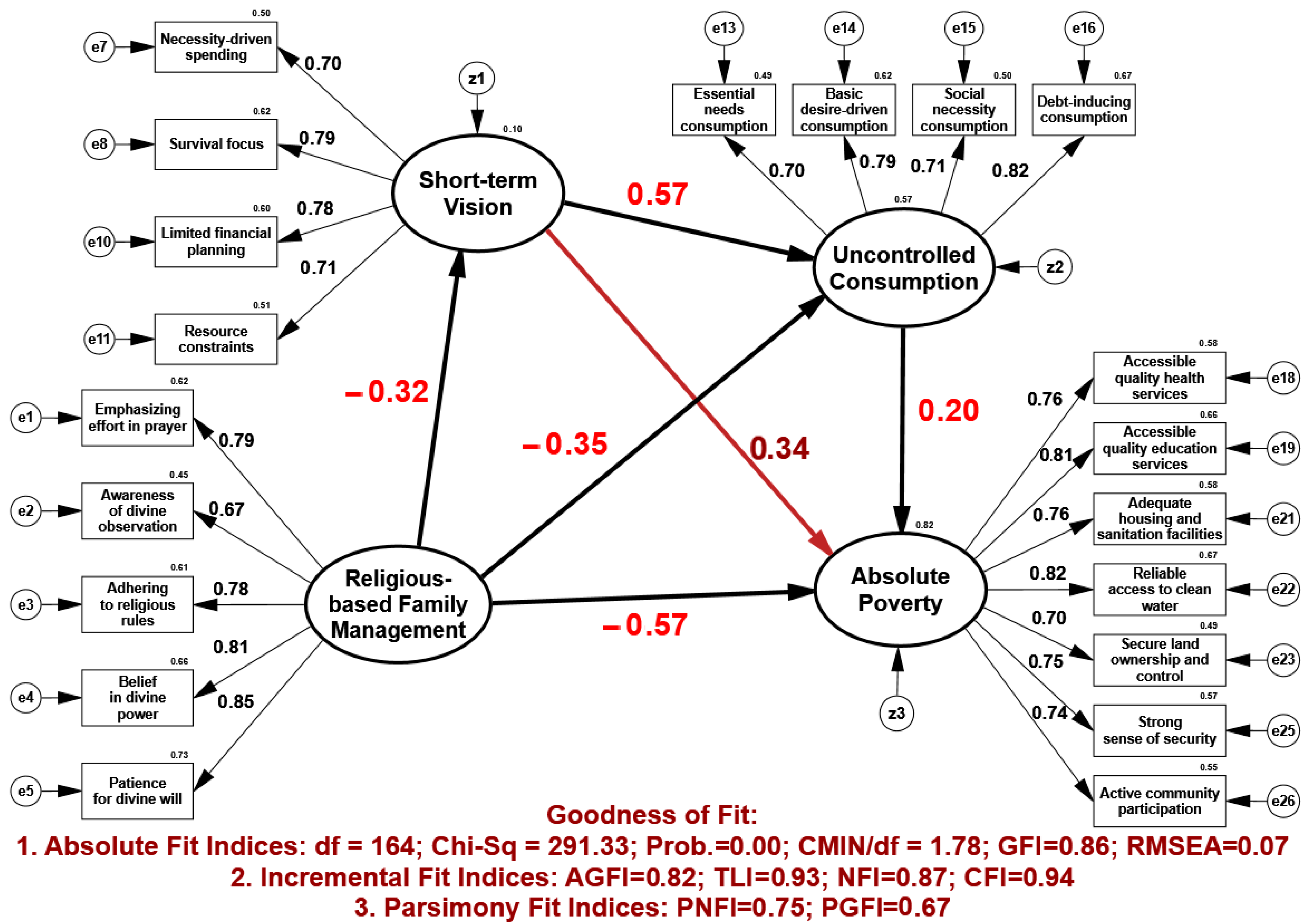

- Religious-based family management significantly reduces short-term vision (β = −0.32), uncontrolled consumption (β = −0.35), and absolute poverty (β = −0.57).

- ▪

- Short-term vision positively influences uncontrolled consumption (β = 0.57) and absolute poverty (β = 0.34).

- ▪

- Uncontrolled consumption also contributes positively to absolute poverty (β = 0.20).

3.3. Hypothesis Testing

- ▪

- RBFM significantly reduces STV (β = −0.32, CR = −3.53) and UC (β = −0.35, CR = −4.38), and directly impacts AP (β = −0.57, CR = −7.61).

- ▪

- STV positively influences UC (β = 0.57, CR = 5.86) and AP (β = 0.34, CR = 4.06).

- ▪

- UC also positively affects AP (β = 0.20, CR = 2.19).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Religious-Based Family Management on Short-Term Vision, Uncontrolled Consumption, and Absolute Poverty

4.2. The Impact of Short-Term Vision on Uncontrolled Consumption and Absolute Poverty

4.3. Uncontrolled Consumption and Its Impact on Absolute Poverty

4.4. Short-Term Vision and Uncontrolled Consumption as Intervening Variables of Religious-Based Family Management on Absolute Poverty

4.4.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

Theoretical Implications

Managerial Implications

- (1)

- Collaboration Between Government and Religious Institutions: Policymakers should collaborate with religious organizations to design programs that integrate financial literacy with religious teachings. For example, combining financial education with moral guidance in religious gatherings, such as sermons or study groups, can encourage disciplined financial behaviors among low-income families.

- (2)

- Community-Based Workshops: Religious leaders and community organizations can organize workshops focusing on budgeting, savings, and investment strategies. These workshops should leverage religious narratives promoting patience, self-control, and accountability, helping families shift their focus from short-term consumption to long-term financial goals.

- (3)

- Incorporating Religious Values into Public Campaigns: Public awareness campaigns can incorporate religious principles to influence financial behavior on a larger scale. For instance, campaigns emphasizing the importance of financial restraint, resource stewardship, and ethical spending can resonate deeply with religious communities, fostering widespread behavioral change.

- (4)

- Policy Development for Poverty Alleviation: Governments can develop poverty alleviation policies that recognize the role of cultural and religious values in shaping financial decisions. These policies could include tax incentives for organizations conducting religion-based financial education programs or grants for community projects that integrate sustainable financial practices with spiritual guidance.

- (5)

- Integration into Education Systems: Introducing financial education courses in schools that align with religious and moral values can create long-term cultural shifts in financial behavior. Embedding such courses into the curricula ensures that future generations are equipped with both practical skills and ethical foundations, fostering disciplined financial management and reducing poverty risks.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RBV | Resource-Based View |

| HCT | Human Capital Theory |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| RBFM | Religious-Based Family Management |

| STV | Short-term Vision |

| UC | Uncontrolled Consumption |

| AP | Absolute Poverty |

References

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2019). Reasoned action in the service of goal pursuit. Psychological Review, 126(5), 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2009). Amos 18 user’s guide. Amos Development Corporation. Available online: https://www.sussex.ac.uk/its/pdfs/Amos_18_Users_Guide.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Attanasio, O., Cattan, S., & Meghir, C. (2022). Early childhood development, human capital, and poverty. Annual Review of Economics, 14, 853–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, O., Meghir, C., Nix, E., & Salvati, F. (2017). Human capital growth and poverty: Evidence from Ethiopia and Peru. Review of Economic Dynamics, 25, 234–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azouz, A., Antheaume, N., & Charles-Pauvers, B. (2022). Looking at the Sky: An ethnographic study of how religiosity influences business family resilience. Family Business Review, 35(2), 184–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrman, J. R., Schott, W., Mani, S., Crookston, B. T., Dearden, K., Duc, L. T., Fernald, L. C. H., & Stein, A. D. (2017). Intergenerational transmission of poverty and inequality: Parental resources and schooling attainment and children’s human capital in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 65(4), 657–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carradus, A., Zozimo, R., & Discua Cruz, A. (2020). Exploring a faith-led open-systems perspective of stewardship in family businesses. Journal of Business Ethics, 163(4), 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casabayó, M., Dávila, J. F., & Rayburn, S. W. (2020). Thou shalt not covet: Role of family religiosity in anti-consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44(5), 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Yu, J., Zhang, Z., Li, Y., Qin, L., & Qin, M. (2024). How human capital prevents intergenerational poverty transmission in rural China: Evidence based on the Chinese general social survey. Journal of Rural Studies, 105, 103220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, M., & Weil, D. (2020). The effect of increasing human capital investment on economic growth and poverty. Journal of Human Capital, 14(1), 43–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs. PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., Lim, W. M., Verma, H. V., & Polonsky, M. (2023). How can we encourage mindful consumption? Insights from mindfulness and religious faith. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 40(3), 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hasmin, & Mariah. (2015). Analisis kemiskinan ditinjau dari tempat tinggal, pekerjaan, pendapatan, dan pendidikan di sulawesi selatan. Jurnal Bisnis & Kewirausahaan, 4(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Heiden-Rootes, K., Wiegand, A., & Bono, D. (2019). Sexual minority adults: A national survey on depression, religious fundamentalism, parent relationship quality & acceptance. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45(1), 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J., Antonides, G., & Nie, F. (2020). Social-psychological factors in food consumption of rural residents: The role of perceived need and habit within the theory of planned behavior. Nutrients, 12(4), 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, W., Pradhan, M., de Groot, R., Sidze, E., Donfouet, H. P. P., & Abajobir, A. (2021). The short-term economic effects of COVID-19 on low-income households in rural Kenya: An analysis using weekly financial household data. World Development, 138, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Jain, V., Sharma, P., Ali, S. A., Shabbir, M. S., & Ramos-Meza, C. S. (2022). The role of sustainable development goals to eradicate the multidimensional energy poverty and improve social wellbeing’s. Energy Strategy Reviews, 42, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2020). Scarcity and cognitive function around payday: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 5(4), 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, C. A. D., Vieira, V., Bonfanti, K., & Mette, F. M. B. (2019). Antecedents of indebtedness for low-income consumers: The mediating role of materialism. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 36(1), 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio, J., & Albuquerque, M. (2021). Negative impact of family religious and spiritual beliefs in schizophrenia—A 2 year follow-up case. European Psychiatry, 64(S1), S683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M. S., Oliver, M., Svenson, A., Simnadis, T., Beck, E. J., Coltman, T., Iverson, D., Caputi, P., & Sharma, R. (2015). The theory of planned behaviour and discrete food choices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1), 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Z. D. (2017). The enduring use of the theory of planned behavior. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 22(6), 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, A. J., Khandpur, N., Polacsek, M., & Rimm, E. B. (2019). What factors influence ultra-processed food purchases and consumption in households with children? A comparison between participants and non-participants in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Appetite, 134(2019), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakutsikwa, B., Britton, J., & Langley, T. (2021). The effect of tobacco and alcohol consumption on poverty in the UK. Addiction, 116(1), 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldekop, J. A., Sims, K. R. E., Karna, B. K., Whittingham, M. J., & Agrawal, A. (2019). Reductions in deforestation and poverty from decentralized forest management in Nepal. Nature Sustainability, 2(5), 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olopade, B. C., Okodua, H., Oladosun, M., & Asaleye, A. J. (2019). Human capital and poverty reduction in OPEC member-countries. Heliyon, 5(8), e02279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B., Kirubakaran, R., Isaac, R., Dozier, M., Grant, L., & Weller, D. (2022). Theory of planned behaviour-based interventions in chronic diseases among low health-literacy population: Protocol for a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, G., & Fényes, H. (2022). Religiosity as a factor supporting parenting and its perceived effectiveness in Hungarian school children’s families. Religions, 13(10), 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P., Deng, L., & Li, H. (2024). Does the county-based poverty reduction policy matter for children’s human capital development? China Economic Review, 85, 102147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajafi, A., Hamhij, N. A., & Ladiqi, S. (2020). The meaning of happiness and religiosity for pre-prosperous family: Study in Manado, Bandar Lampung, and Yogyakarta. Al-Ihkam: Jurnal Hukum Dan Pranata Sosial, 15(1), 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, D., Spyreli, E., Woodside, J., McKinley, M., & Kelly, C. (2022). Parental perceptions of the food environment and their influence on food decisions among low-income families: A rapid review of qualitative evidence. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentschler, J., & Leonova, N. (2023). Global air pollution exposure and poverty. Nature Communications, 14(1), 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, A. M. (2021). Mitigating poverty through the formation of extended family households: Race and ethnic differences. Social Problems, 67(4), 782–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarofim, S., Minton, E., Hunting, A., Bartholomew, D. E., Zehra, S., Montford, W., Cabano, F., & Paul, P. (2020). Religion’s influence on the financial well-being of consumers: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(3), 1028–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, G. (2019). Religion and poverty. Palgrave Communications, 5(1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy-skeffington, J. (2020). The effects of socioeconomic status on cognitive functioning and decision-making. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, G. M. F., & Leder, S. M. (2022). Energy poverty: The paradox between low income and increasing household energy consumption in Brazil. Energy and Buildings, 268, 112234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siregar, N. A., Amri, K., & Riyaldi, M. H. (2023). Peran belanja pemerintah daerah dalam memoderasi pengaruh zakat terhadap kemiskinan di provinsi aceh. Journal of Law and Economics, 2(2), 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamsah, H. (2011). Analisis kemiskinan di kota makassar. Universitas Hasanuddin. [Google Scholar]

- Tamsah, H., & Nurung, J. (2024). The dynamics of poverty in South Sulawesi: Perspectives from the community, NGOs, and government. Economics and Digital Business Review, 5(2), 166–176. Available online: https://ojs.stieamkop.ac.id/index.php/ecotal/article/view/1127/816 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Tamsah, H., Ilyas, G. B., Nur, Y., Yusriadi, Y., & Asrifan, A. (2021). Uncontrolled consumption and life quality of low-income families: A study of three major tribes in south Sulawesi. Management Science Letters, 10(4), 1171–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamsah, H., Ilyas, G. B., Nurung, J., & Yusriadi, Y. (2023). Model testing and contribution of antecedent variable to absolute poverty: Low income family perspective in Indonesia. Sustainability, 15(8), 6894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laar, S., & Braeken, J. (2021). Understanding the comparative fit Index: It’s all about the base! Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 26(26), 1–23. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/pare/vol26/iss1/26 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Wang, Q. S., Hua, Y. F., Tao, R., & Moldovan, N. C. (2021). Can health human capital help the Sub-Saharan Africa out of the poverty trap? An ARDL model approach. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 697826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widiastuti, T., Mawardi, I., Zulaikha, S., Herianingrum, S., Robani, A., Al Mustofa, M. U., & Atiya, N. (2022). The nexus between Islamic social finance, quality of human resource, governance, and poverty. Heliyon, 8(12), e11885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, H. R., Hati, S. R. H., Ekaputra, I. A., & Kassim, S. (2024). The impact of religiosity and financial literacy on financial management behavior and well-being among Indonesian Muslims. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothesis | Statement | Theoretical Support | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Religious-based family management (RBFM) negatively affects short-term vision (STV). | Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) | (Ajzen, 2020; Gupta et al., 2023; McDermott et al., 2015) |

| H2 | Religious-based family management (RBFM) negatively affects uncontrolled consumption (UC). | Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) | (Ajzen, 2020; Gupta et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2020) |

| H3 | Religious-based family management (RBFM) negatively affects absolute poverty (AP). | Human Capital Theory (HCT) | (Behrman et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2024; Tamsah et al., 2023) |

| H4 | Short-term vision (STV) positively affects uncontrolled consumption (UC). | Behavioral Economics/TPB | (Gupta et al., 2023; Janssens et al., 2021; Mani et al., 2020) |

| H5 | Short-term vision (STV) positively affects absolute poverty (AP). | Behavioral Economics/TPB | (Janssens et al., 2021; Mani et al., 2020; Paul et al., 2022) |

| H6 | Uncontrolled consumption (UC) positively affects absolute poverty (AP). | Human Capital Theory (HCT) and Consumption Theory | (Behrman et al., 2017; Oldekop et al., 2019; Siregar et al., 2023) |

| H7 | Religious-based family management (RBFM) indirectly reduces absolute poverty (AP) through its impact on short-term vision (STV) and uncontrolled consumption (UC). | Human Capital Theory (HCT) and TPB | (Ajzen, 2020; Chen et al., 2024; Colin & Weil, 2020) |

| Demographic Items | Freq. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1. Between 20 and 30 | 21 | 12.21 |

| 2. Between 31 and 40 | 47 | 27.33 | |

| 3. Between 41 and 50 | 104 | 60.47 | |

| Amount | 172 | 100.00 | |

| Education | 1. Bachelor | 1 | 0.58 |

| 2. Finished high school | 12 | 6.98 | |

| 3. High school graduate | 29 | 16.86 | |

| 4. Elementary school | 53 | 30.81 | |

| 5. Did not finish elementary school | 32 | 18.60 | |

| 6. Never went to school | 45 | 26.16 | |

| Amount | 172 | 100.00 | |

| Origin | 1. Makassar City | 73 | 42.44 |

| 2. Jeneponto Regency | 25 | 14.53 | |

| 3. Selayar Islands Regency | 18 | 10.47 | |

| 4. Bone County | 20 | 11.63 | |

| 5. North Luwu Regency | 19 | 11.05 | |

| 6. North Toraja Regency | 17 | 9.88 | |

| Amount | 172 | 100.00 | |

| Family Income | 1. More than IDR 150,000 per day | 2 | 1.16 |

| 2. IDR 101,000–IDR 150,000 per day | 9 | 5.23 | |

| 3. IDR 51,000–IDR 100,000 per day | 47 | 27.33 | |

| 4. IDR 20,000–IDR 50,000 per day | 63 | 36.63 | |

| 5. Less than IDR 20,000 per day | 51 | 29.65 | |

| Amount | 172 | 100.00 | |

| Number of Family Members | 1. More than 9 people | 0 | 0.00 |

| 2. 7–9 people | 17 | 9.88 | |

| 3. 4–6 people | 90 | 52.33 | |

| 4. 1–3 people | 65 | 37.79 | |

| Amount | 172 | 100.00 | |

| Variable | Indicator | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Religious-based family management (RBFM) | Emphasizing effort in prayer (RBFM1) | We always strive earnestly in prayer. |

| Awareness of divine observation (RBFM2) | We feel constantly watched over by God in all our actions. | |

| Adhering to religious rules (RBFM3) | We follow religious rules with discipline. | |

| Belief in divine power (RBFM4) | We believe that God’s power will help us through every problem. | |

| Patience for divine will (RBFM5) | We remain patient with God’s will, even in difficult times. | |

| Emphasizing effort in prayer (RBFM6) | We continuously pray and strive for a better life. | |

| Short-term vision (STV) | Necessity-driven spending (STV1) | If we have money, there are many needs we want to fulfill. |

| Survival focus (STV2) | We only think about how to meet today’s needs. | |

| Lack of savings orientation (STV3) | We spend today’s earnings immediately and think about tomorrow later. | |

| Limited financial planning (STV4) | We do not plan our finances for daily needs, emergencies, or savings. | |

| Resource constraints (STV5) | We feel incapable of managing our income properly. | |

| Uncontrolled consumption (UC) | Unplanned consumption (UC1) | We do not have a shopping plan; we spend based on today’s earnings. |

| Essential needs consumption (UC2) | We tend to follow the desires of our children or family members without considering actual needs. | |

| Basic desire-driven consumption (UC3) | If we have extra money, we buy items like TVs or mobile phones, even if they are not urgent. | |

| Social necessity consumption (UC4) | We focus more on meeting today’s needs without thinking about tomorrow’s necessities. | |

| Debt-inducing consumption (UC5) | Sometimes we borrow money to buy something and only repay it when we have money. | |

| Absolute poverty (AP) | Adequate and quality food supply (AP1) | We lack adequate food and drink on a daily basis. |

| Accessible quality health services (AP2) | We cannot afford healthcare costs at community health centers due to financial limitations. | |

| Accessible quality education services (AP3) | We are unable to send our children to senior high school like others can. | |

| Available employment and business opportunities (AP4) | We struggle to find decent jobs that meet everyone’s expectations. | |

| Adequate housing and sanitation facilities (AP5) | We live in homes with inadequate conditions and poor sanitation. | |

| Reliable access to clean water (AP6) | We cannot afford to purchase or access clean water for daily use. | |

| Secure land ownership and control (AP7) | We do not own land, so we must live as tenants or stay with others. | |

| Sustainable environmental and natural resource conditions (AP8) | We lack the capacity to maintain the environment and surrounding natural resources. | |

| Strong sense of security (AP9) | We often feel insecure due to the absence of health insurance, savings, or proper housing. | |

| Active community participation (AP10) | We cannot actively participate in government programs or community development activities. | |

| Manageable family dependency ratio (AP11) | We have many dependents in our family, making it difficult to manage the household economy. |

| Variable | Item | Standardized Estimate | Estimate | Standard Error | Critical Ratio | p-Value | Reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | |||||||

| Religious-based family management (RBFM) | Emphasizing effort in prayer (RBFM1) | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.08 | 10.96 | *** | 0.99 | 0.94 |

| Awareness of divine observation (RBFM2) | 0.67 | 1.07 | 0.12 | 9.00 | *** | |||

| Adhering to religious rules (RBFM3) | 0.78 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Belief in divine power (RBFM4) | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.08 | 11.34 | *** | |||

| Patience for divine will (RBFM5) | 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.08 | 12.06 | *** | |||

| Emphasizing effort in prayer (RBFM6) | Deleted item | |||||||

| Short-term vision (STV) | Necessity-driven spending (STV1) | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.84 | |||

| Survival focus (STV2) | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.11 | 9.09 | *** | |||

| Lack of savings orientation (STV3) | Deleted item | |||||||

| Limited financial planning (STV4) | 0.78 | 1.08 | 0.12 | 8.97 | *** | |||

| Resource constraints (STV5) | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.11 | 8.35 | *** | |||

| Uncontrolled consumption (UC) | Unplanned consumption (UC1) | Deleted item | 0.95 | 0.90 | ||||

| Essential needs consumption (UC2) | 0.70 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Basic desire-driven consumption (UC3) | 0.79 | 1.15 | 0.13 | 9.20 | *** | |||

| Social necessity consumption (UC4) | 0.71 | 0.99 | 0.12 | 8.38 | *** | |||

| Debt-inducing consumption (UC5) | 0.82 | 1.15 | 0.12 | 9.47 | *** | |||

| Absolute poverty (AP) | Adequate and quality food supply (AP1) | Deleted item | 0.98 | 0.85 | ||||

| Accessible quality health services (AP2) | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.08 | 11.19 | *** | |||

| Accessible quality education services (AP3) | 0.81 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Available employment and business opportunities (AP4) | Deleted item | |||||||

| Adequate housing and sanitation facilities (AP5) | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.07 | 11.16 | *** | |||

| Reliable access to clean water (AP6) | 0.82 | 0.94 | 0.08 | 12.37 | *** | |||

| Secure land ownership and control (AP7) | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.09 | 9.93 | *** | |||

| Sustainable environmental and natural resource conditions (AP8) | Deleted item | |||||||

| Strong sense of security (AP9) | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.08 | 11.00 | *** | |||

| Active community participation (AP10) | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.08 | 10.75 | *** | |||

| Manageable family dependency ratio (AP11) | Deleted item | |||||||

| Model Fit Testing | Cutoff Point | Result | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Absolute Fit Indices: | |||

| Chi-Square | df = 164; X2 = 194.88 | 291.33 | Marginal |

| Significance | ≥0.05 (Van Laar & Braeken, 2021) | 0.00 | Marginal |

| CMIN/df | ≤3.00 (even <5.00) (Dash & Paul, 2021) | 1.78 | Fit |

| GFI | ≥0.90 (Hair et al., 2010) | 0.86 | Marginal |

| RMSEA | 0.03–0.08 (Arbuckle, 2009) | 0.07 | Fit |

| 2. Incremental Fit Indices: | |||

| AGFI | ≥0.90 (Hair et al., 2010) | 0.82 | Marginal |

| TLI | ≥0.90 (Arbuckle, 2009) | 0.93 | Fit |

| NFI | ≥0.90 (Dash & Paul, 2021) | 0.87 | Marginal |

| CFI | ≥0.90 (Van Laar & Braeken, 2021) | 0.94 | Fit |

| 3. Parsimony Fit Indices: | |||

| PNFI | >0.50 (Dash & Paul, 2021) | 0.75 | Fit |

| PGFI | >0.50 (Dash & Paul, 2021) | 0.67 | Fit |

| Hypothesis | Standardized Estimate | Estimate | Standard Error | Critical Ratio | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Religious-based family management (RBFM) → short-term vision (STV) | −0.32 | −0.57 | 0.16 | −3.53 | *** | Accepted |

| H2: Religious-based family management (RBFM) → uncontrolled consumption (UC) | −0.35 | −0.58 | 0.13 | −4.38 | *** | Accepted |

| H3: Religious-based family management (RBFM) → absolute poverty (AP) | −0.57 | −1.22 | 0.16 | −7.61 | *** | Accepted |

| H4: Short-term vision (STV) → uncontrolled consumption (UC) | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.09 | 5.86 | *** | Accepted |

| H5: Short-term vision (STV) → absolute poverty (AP) | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.10 | 4.06 | *** | Accepted |

| H6: Uncontrolled consumption (UC) → absolute poverty (AP) | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 2.19 | 0.03 | Accepted |

| H7: Religious-based family management (RBFM) → short-term vision (STV) → uncontrolled consumption (UC) → absolute poverty (AP) | −0.21 | Estimate/bootstrap (two-tailed significance—BC) | 0.00 | Accepted | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasmin, H.; Nurung, J.; Ilyas, G.B. Religious-Based Family Management and Its Impact on Consumption Patterns and Poverty: A Human Resource and Management Perspective. Economies 2025, 13, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030070

Hasmin H, Nurung J, Ilyas GB. Religious-Based Family Management and Its Impact on Consumption Patterns and Poverty: A Human Resource and Management Perspective. Economies. 2025; 13(3):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030070

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasmin, Hasmin, Jumiaty Nurung, and Gunawan Bata Ilyas. 2025. "Religious-Based Family Management and Its Impact on Consumption Patterns and Poverty: A Human Resource and Management Perspective" Economies 13, no. 3: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030070

APA StyleHasmin, H., Nurung, J., & Ilyas, G. B. (2025). Religious-Based Family Management and Its Impact on Consumption Patterns and Poverty: A Human Resource and Management Perspective. Economies, 13(3), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030070