Analysis of the Impact of SMEs’ Production Output on Kazakhstan’s Economic Growth Using the ARDL Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

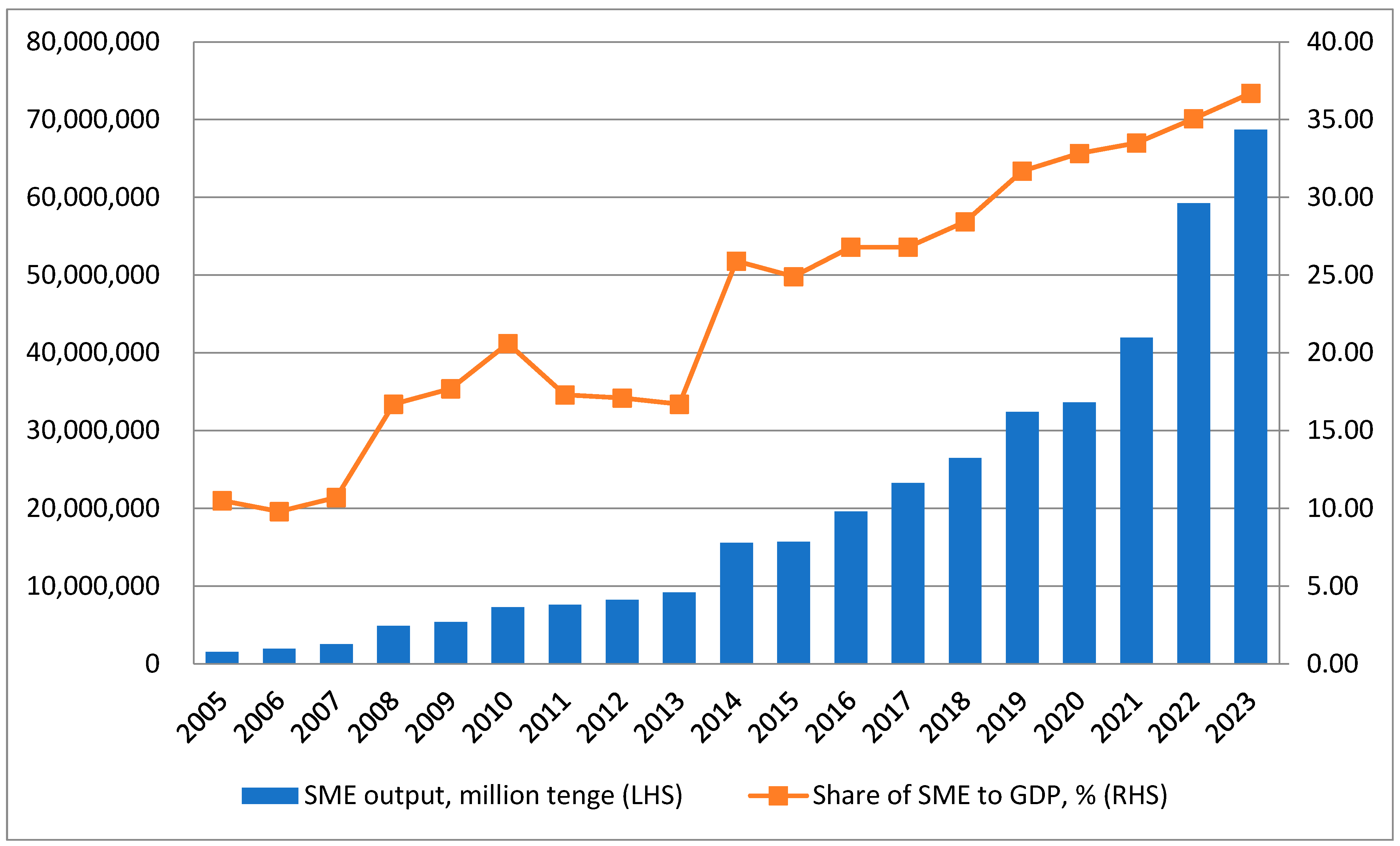

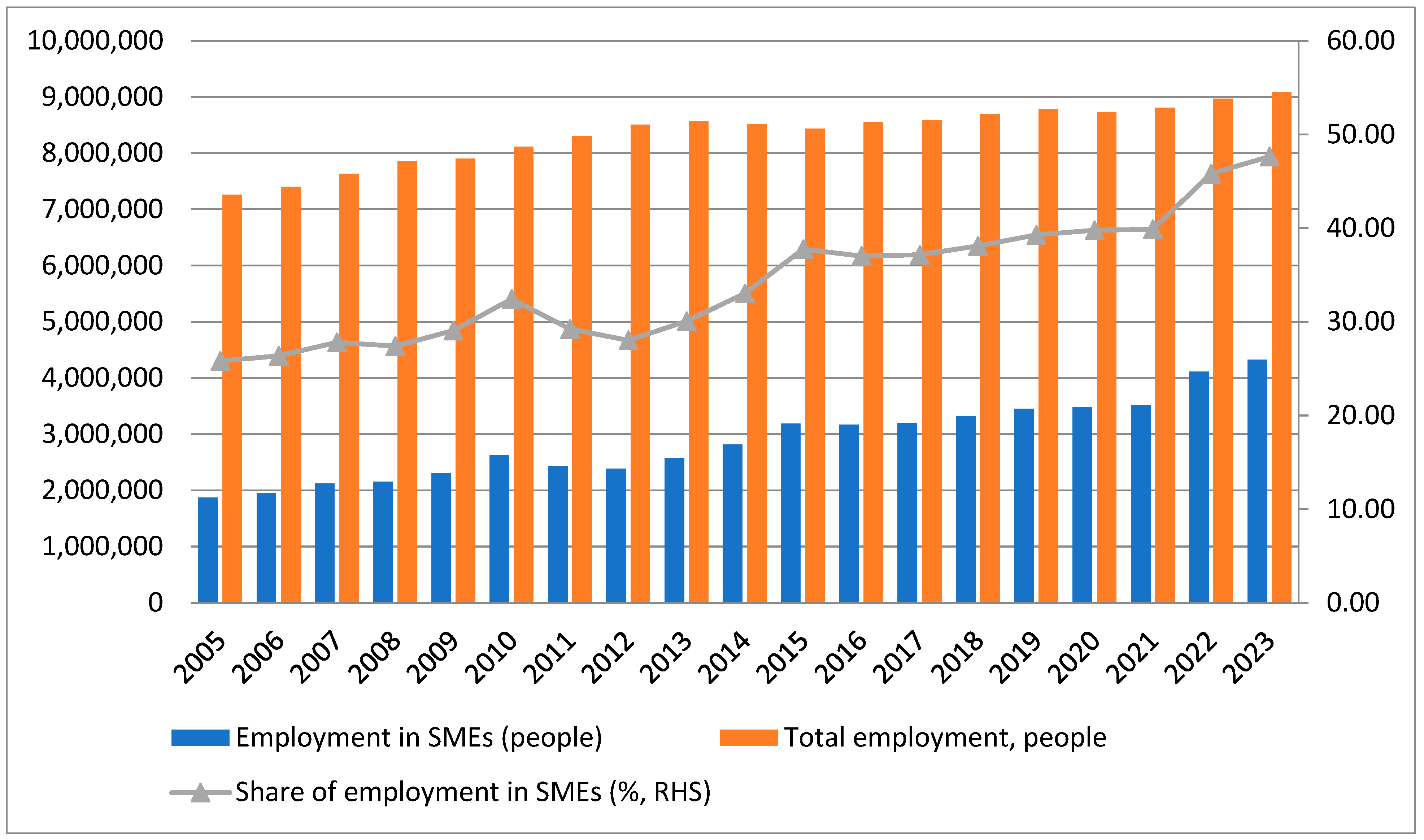

2. Features of SMEs in the Republic of Kazakhstan

3. Literature Review

4. Methods and Description of the Variable

4.1. The Model Specification

4.2. Tools of Estimation

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Unit Root Test Results

5.3. ARDL Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alauddin, M., Rahman, M. Z., & Rahman, M. (2015). Investigating the performance of SME sector in Bangladesh: An evaluative study. International Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Research, 3(6), 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Amirat, A., & Zaidi, M. (2020). Estimating GDP growth in Saudi Arabia under the government’s vision 2030: A knowledge-based economy approach. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(3), 1145–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, S. K., & Amoah, A. K. (2018). The role of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to employment in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Economics Research, 7(5), 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amusa, H., Amusa, K., & Mabugu, R. (2009). Aggregate demand for electricity in South Africa: An analysis using the bounds testing approach to cointegration. Energy Policy, 37(10), 4167–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. (1982). Small industry in developing countries: A discussion of issues. World Development, 10(11), 913–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arent, A., Bojar, M., Diniz, F., & Duarte, N. (2015). The role of SMEs in sustainable regional development and local business integration: The case of Lublin region (Poland). Regional Science Inquiry, VII(2), 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Regional Studies, 38(8), 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykan, E., Aksoylu, S., & Sönmez, E. (2013). Effects of support programs on corporate strategies of small and medium-sized enterprises. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 99, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 407–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrancea, L. M. (2022). Determinants of economic growth across the European Union: A panel data analysis on small and medium enterprises. Sustainability, 14(8), 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2005). SMEs, growth, and poverty: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Economic Growth, 10, 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekzhanova, T., Aliyev, M., Tussibayeva, G., Altynbekov, M., & Akhmetova, A. (2023). The development of small and medium-sized businesses and its impact on the trend of unemployment in Kazakhstan. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 17(4), 73–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaldun, E. R., Yudoko, G., & Prasetio, E. A. (2024). Developing a theoretical framework of export-oriented small enterprises: A multiple case study in an emerging country. Sustainability, 16(24), 11132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittithaworm, C., Islam, A., Keawchana, T., & Yusuf, D. H. M. (2011). Factors affecting business success of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Thailand. Asian Social Science, 7(5), 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, D., Al-Alawi, A. N., Syzdykova, A., & Abubakirova, A. (2021). Attractiveness and difficulties of SMEs in Kazakhstan economy. Review of Applied Socio-Economic Research, 21(1), 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cravo, T. A., Becker, B., & Gourlay, A. (2015). Regional growth and SMEs in Brazil: A spatial panel approach. Regional Studies, 49(12), 1995–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debela, G. (2019). The effect of real exchange rate on the trade balance of ethiopia: Does marshall lerner condition holds? evidence from (VECM) analysis. Available online: https://etd.aau.edu.et/server/api/core/bitstreams/c73b13bf-3aed-42b1-9153-2a7e5834a9c6/content (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Dixit, A., & Pandey, A. K. (2011). SMEs and Economic Growth in India: Cointegration Analysis. IUP Journal of Financial Economics, 9(2), 41. [Google Scholar]

- Durlauf, S. N. (2005). Growth econometrics. Handbook of economic growth (Chapter 8). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Dvouletý, O., Gordievskaya, A., & Procházka, D. A. (2018). Investigating the relationship between entrepreneurship and regional development: Case of developing countries. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etuk, R. U., Etuk, G. R., & Michael, B. (2014). Small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs) and Nigeria’s economic development. Small, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghina, S. C., Botezatu, M. A., Hosszu, A., & Simionescu, L. N. (2020). Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): The Engine of Economic Growth through Investments and Innovation. Sustainability, 12(1), 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoselitz, B. F. (1959). Small industry in underdeveloped countries. The Journal of Economic History, 19(4), 600–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. W. (2010). SMEs and economic growth: Entrepreneurship or employment. ICIC Express Letters, 4(6), 2275–2280. [Google Scholar]

- Inegbedion, H. E., Thikan, P. R., David, J. O., Ajani, J. O., & Peter, F. O. (2024). Small and medium enterprise (SME) competitiveness and employment creation: The mediating role of SME growth. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Južnik Rotar, L., Kontošić Pamić, R., & Bojnec, Š. (2019). Contributions of small and medium enterprises to employment in the European Union countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 3296–3308. [Google Scholar]

- Karadag, H. (2016). The role of SMEs and entrepreneurship on economic growth in emerging economies within the post-crisis era: An analysis from Turkey. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 4(1), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, H., Sentürk, C., Sungur, O., & Kiris, H. M. (2010, June 8–9). The importance of SMEs in developing economies. 2nd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/153446896.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Kumar, R. R., Stauvermann, P. J., Loganathan, N., & Kumar, R. D. (2015). Exploring the role of energy, trade and financial development in explaining economic growth in South Africa: A revisit. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 52, 1300–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R., & Renelt, D. (1992). A sensitivity analysis of cross-country growth regressions. The American Economic Review, 82, 942–963. [Google Scholar]

- Lilimberg, S., & Selezneva, T. (2019). Analysis of trends and patterns of development of small and medium-sized businesses in the Kostanay region of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Regionalistika [Regionalistics], 6(2), 64–74. (In Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukács, E. (2005). The economic role of SMEs in world economy, especially in Europe. European Integration Studies, 4(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Makkonen, T., & Leick, B. (2019). Locational challenges and opportunities for SMEs in border regions. European Planning Studies, 28, 2078–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N. G. (1992). Commentary: The search for growth. In Proceedings-economic policy symposium-Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (pp. 87–92). Citeseer. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, F., Wei, L., & Siraj, M. (2021). Small and medium-sized enterprises and economic growth in Pakistan: An ARDL bounds cointegration approach. Heliyon, 7(2), e06340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melwani, R. (2018). Entrepreneurship development and economic development: A literature analysis. Aweshkar, 24(1), 124–149. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. P. (1990). Survival and growth of ındependent firms and corporate affiliates in metro and nonmetro America. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Mrva, M., & Stachova, P. (2014). Regional development and support of SMEs–how university project can help. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 110, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, P. (2007). Entrepreneurship in the region: Breeding ground for nascent entrepreneurs? Small Business Economics, 27, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujahid, N., & Begam, A. (2019). SMEs output and GDP growth: A dynamic perspective. Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 9(1), 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naradda Gamage, S. K., Ekanayake, E. M. S., Abeyrathne, G. A. K. N. J., Prasanna, R. P. I. R., Jayasundara, J. M. S. B., & Rajapakshe, P. S. K. (2020). A review of global challenges and survival strategies of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Economies, 8(4), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, S., & Narayan, P. K. (2004). Determinants of demand for Fiji’s exports: An empirical investigation. The Developing Economies, 42(1), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, S., & Rostom, A. M. (2013, October 1). SME contributions to employment, job creation, and growth in the Arab world. Job Creation, and Growth in the Arab World. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano, P., & Schivardi, F. (2003). Firm size distribution and growth. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 105(2), 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L., & Mishra, V. (2018). Stock market development and economic growth: Empirical evidence from China. Economic Modelling, 68, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, V. M. (2012, September 6–7). Comparative analysis of development of SMEs in developed and developing countries. The 2012 International Conference on Business and Management (pp. 1–20), Phuket, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Parrilli, M. D. (2007). Inclusion versus fragmentation: Different responses to liberalisation in European and Latin American small and medium enterprises. In SME cluster development: A dynamic view of survival clusters in developing countries (pp. 30–53). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (1995). An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis (Vol. 9514, pp. 371–413). Department of Applied Economics, University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P. C. B., & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a Unit Root in Time Series Regression. Biometrika, 75(2), 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulka, B. M., & Gawuna, M. S. (2022). Contributions of SMEs to employment, gross domestic product, economic growth and development. Jalingo Journal of Social and Management Sciences, 4(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sakib, M. N., Rabbani, M. R., Hawaldar, I. T., Jabber, M. A., Hossain, J., & Sahabuddin, M. (2022). Entrepreneurial competencies and SMEs’ performance in a developing economy. Sustainability, 14(20), 13643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidek, S., Rosli, M. M., Hasbolah, H., & Khadri, N. A. M. (2020). An overview on criteria of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) across the economies: A random selection of countries. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(4), 1312–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M., & Dolnicar, S. (2018). Entrepreneurship opportunities. In S. Dolnicar (Ed.), Peer-to-peer accommodation networks: Pushing the boundaries (pp. 77–86). Goodfellow Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, A. (2015). Study of the dependence of regional budget from the small business development in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Naukovedenie, 7(2). Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/issledovanie-zavisimosti-dohodov-regionalnyh-byudzhetov-respubliki-kazahstan-ot-razvitiya-malogo-biznesa/viewer (accessed on 27 October 2024). (In Russian).

- Staley, E., & Morse, R. (1965). Modern small industry for developing countries. McGraw-Hill Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Surya, B., Menne, F., Sabhan, H., Suriani, S., Abubakar, H., & Idris, M. (2021). Economic growth, increasing productivity of SMEs, and open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syzdykova, A., & Azretbergenova, G. (2023). Assessment of the contribution of small and medium enterprises in the economy of Turkestan region. Memlekettik Audit-State Audit, 61(4), 158–169. (In Kazakh). [Google Scholar]

- Tambunan, T. H. (2006). Development of small & medium enterprises in Indonesia from the Asia-Pacific perspective. LPFE-USAKTI, LPFE. [Google Scholar]

- Uruzbaeva, N. (2016). Problems and Ways of Improving the Business Climate in the Regions. Ekonomika Regiona [Economy of region], 12(1), 150–161. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Uruzbaeva, N. (2022). Assessment of the Contribution of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises to the Output of the Cities of Republican Significance in Kazakhstan. Ekonomika Regiona [Economy of Region], 18(3), 867–881. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2022). Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) finance. Washington, D.C. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Zafar, A., & Mustafa, S. (2017). SMEs and its role in economic and socio-economic development of Pakistan. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 6(4). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3085425 (accessed on 17 October 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarubina, V., Zarubin, M., Yessenkulova, Z., Gumarova, T., Daulbayeva, A., Meimankulova, Z., & Kurmangalieva, A. (2024). Sustainable Development of Small Business in Kazakhstan. Economies, 12(9), 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enterprise | Number of Employees | Annual Revenue (MCI *) |

|---|---|---|

| Micro | Not more than 15 | 30,000 MCI |

| Small | Not more than 100 | 300,000 MCI |

| Medium | 101–250 | 3,000,000 MCI |

| Including | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Legal Entities of Small Enterprises | Legal Entities of Medium Enterprises | Individual Entrepreneurs | Peasant or Farm Enterprises | |

| Republic of Kazakhstan | 2002.199 | 360.268 | 2.940 | 1369.043 | 269.948 |

| Abay | 53.269 | 4.874 | 53 | 37.821 | 10.521 |

| Akmola | 57.919 | 9.203 | 121 | 41.645 | 6.950 |

| Aktobe | 83.819 | 12.742 | 122 | 61.850 | 9.105 |

| Almaty | 134.628 | 13.878 | 148 | 91.789 | 28.813 |

| Atyrau | 65.045 | 9.242 | 127 | 51.607 | 4.069 |

| Batys Kazakhstan | 57.653 | 7.831 | 97 | 40.156 | 9.569 |

| Zhambyl | 106.779 | 9.312 | 60 | 67.167 | 30.240 |

| Zhetisu | 58.914 | 4.690 | 50 | 33.630 | 20.544 |

| Karagandy | 99.190 | 19.162 | 181 | 69.770 | 10.077 |

| Kostanay | 64.286 | 9.755 | 159 | 47.168 | 7.204 |

| Kyzylorda | 67.180 | 6.245 | 71 | 48.383 | 12.481 |

| Mangystau | 79.742 | 11.805 | 121 | 63.829 | 3.987 |

| Pavlodar | 54.578 | 11.983 | 117 | 36.936 | 5.542 |

| Soltustik Kazakhstan | 34.891 | 6.873 | 119 | 22.933 | 4.966 |

| Turkistan | 206.855 | 12.416 | 84 | 113.084 | 81.271 |

| Ulytau | 18.791 | 1.766 | 15 | 13.145 | 3.865 |

| Shygys Kazakhstan | 62.616 | 9.131 | 129 | 44.339 | 9.017 |

| Astana city | 227.386 | 71.559 | 253 | 153.765 | 1.809 |

| Almaty city | 340.132 | 106.543 | 755 | 229.685 | 3.149 |

| Shymkent city | 128.526 | 21.258 | 158 | 100.341 | 6.769 |

| Indicator | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Share of SMEs in GDP | 40% |

| Share of medium-sized companies in GDP | 20% |

| Employment (million people) in medium-sized enterprises | 5 |

| Growth of average real labor productivity in medium-sized enterprises (per enterprise) | 50% |

| The share of investments in fixed capital of medium-sized enterprises in the total volume of investments in fixed capital of all business entities | 15% |

| lnGDP | lnSMEO | lnGE | lnDC | lnTO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 17.37705 | 16.31863 | 15.81182 | 16.17475 | 4.069187 |

| Median | 17.49625 | 16.56073 | 15.86859 | 16.30919 | 4.032805 |

| Maximum | 18.59674 | 18.04541 | 17.10242 | 17.14532 | 4.403526 |

| Minimum | 15.84242 | 14.24992 | 14.48136 | 14.76797 | 3.725731 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.793293 | 1.124219 | 0.779539 | 0.545030 | 0.193061 |

| Skewness | −0.326505 | −0.278967 | −0.128454 | −0.659583 | 0.231035 |

| Kurtosis | 2.129689 | 2.106341 | 1.993360 | 3.833666 | 2.244950 |

| Jarque–Bera | 0.937226 | 0.878684 | 0.854467 | 1.927865 | 0.620357 |

| Probability | 0.625870 | 0.644460 | 0.652311 | 0.381390 | 0.733316 |

| Variables | ADF | PP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Statistic | Prob. | t-Statistic | Prob. | |

| −2.306721 | 0.1804 | −2.671893 | 0.0980 | |

| −3.698904 | 0.0145 ** | −3.812974 | 0.0116 ** | |

| −1.262711 | 0.6228 | −1.593694 | 0.4652 | |

| −4.977671 | 0.0012 *** | −4.977671 | 0.0012 *** | |

| −1.276422 | 0.6133 | −0.570719 | 0.8544 | |

| −4.618166 | 0.0026 *** | −5.588197 | 0.0004 *** | |

| 0.566682 | 0.9839 | −2.328781 | 0.1742 | |

| −3.962266 | 0.0086 *** | −4.010209 | 0.0078 *** | |

| −1.779783 | 0.3776 | −1.750057 | 0.3912 | |

| −4.573424 | 0.0026 *** | −4.575470 | 0.0026 *** | |

| 5% Critical Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Statistic | Value | k | I0 Bound | I1 Bound |

| F-statistic | 4.303702 | 4 | 2.86 | 4.01 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0993 | 0.0075 | 3.5011 | 0.0010 | |

| −0.1207 | 0.0708 | −1.6872 | 0.1023 | |

| 0.0704 | 0.0039 | 9.0920 | 0.0000 | |

| 0.3987 | 0.1649 | 2.3876 | 0.0020 | |

| 7.8453 | 0.5828 | 12.3605 | 0.0000 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D(lnSMEO) | −0.8006 | 0.1562 | −4.8473 | 0.0000 |

| D(lnSMEO(−1)) | 0.6830 | 0.1804 | 3.9579 | 0.0004 |

| D(lnGE) | 0.9013 | 0.1899 | 4.5780 | 0.0000 |

| D(lnGE(–1)) | −0.7647 | 0.1873 | −4.1201 | 0.0006 |

| D(lnDC) | 0.0260 | 0.0013 | 10.3079 | 0.0000 |

| CointEq(–1) | −0.2754 | 0.0360 | −7.6810 | 0.0000 |

| Stability Test: Ramsey Reset Test | ||||

| F-statistic: 2.737880 | Probability: 0.1065 | |||

| Heteroscedasticity Test: Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey Test | ||||

| F-statistic: 1.121100 | Probability: 0.3725 | |||

| Autocorrelation Test: Breusch–Godfrey LM Test | ||||

| F-statistic: 0.887129 | Probability: 0.4206 | |||

| Normal Distribution Test | ||||

| Skewness: 0.310818 Kurtosis: 2.593196 Jarque–Bera: 1.149835 Probability: 0.562751 | ||||

| CUSUM: Stable CUSUMQ: Stable R2: 0.8013 Adjusted R2: 0.7757 F-statistic: 4326.027(0000) Durbin–Watson: 2.036730 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Syzdykova, A.; Azretbergenova, G. Analysis of the Impact of SMEs’ Production Output on Kazakhstan’s Economic Growth Using the ARDL Method. Economies 2025, 13, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13020038

Syzdykova A, Azretbergenova G. Analysis of the Impact of SMEs’ Production Output on Kazakhstan’s Economic Growth Using the ARDL Method. Economies. 2025; 13(2):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13020038

Chicago/Turabian StyleSyzdykova, Aziza, and Gulmira Azretbergenova. 2025. "Analysis of the Impact of SMEs’ Production Output on Kazakhstan’s Economic Growth Using the ARDL Method" Economies 13, no. 2: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13020038

APA StyleSyzdykova, A., & Azretbergenova, G. (2025). Analysis of the Impact of SMEs’ Production Output on Kazakhstan’s Economic Growth Using the ARDL Method. Economies, 13(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13020038