1. Introduction

Regional tax compliance plays a central role in strengthening provincial fiscal capacity in Indonesia, particularly as regional governments increasingly rely on Pendapatan Asli Daerah (PAD; Regional Own-Source Revenue) to support autonomy and public service delivery. At the national level, tax revenues have grown substantially over the past decade and now account for the dominant share of central government income, financing the bulk of state spending on infrastructure, education, health, and social protection (

Harjowiryono, 2019;

Badan Pusat Statistik, 2014,

2024). However, tax effort indicators suggest that Indonesia collects only around half of its potential tax revenue, with estimates placing effective tax effort at approximately 43–59% of capacity. This gap indicates that improvements in tax compliance remain crucial not only at the national level but also within subnational governments.

A similar pattern is evident in provincial public finances. Between 2014 and 2024, provincial own-source revenues and regional tax revenues increased significantly, yet their growth has been uneven across regions. Some provinces, such as Southeast Sulawesi, experienced extraordinary growth in regional tax revenue, while others, including South Sumatra and several eastern provinces, recorded persistent declines or stagnation. On average, regional taxes have grown faster than total regional revenues and PAD, but large disparities across provinces indicate differences in administrative capacity, enforcement, and taxpayer behavior (

Directorate General of Fiscal Balance, 2018). At the same time, ratios of PAD to total regional revenue show that most provinces remain fiscally dependent on central transfers, with only a minority approaching moderate autonomy (

Directorate General of Fiscal Balance, 2019;

Yulianti et al., 2021). These conditions underscore the importance of improving provincial tax compliance as a key pathway to strengthening regional fiscal independence and reducing vertical fiscal dependency (

Biswan, 2022;

Rahmawati et al., 2024).

Within this broader context, the framework of fiscal federalism is highly relevant. Indonesia’s decentralization reforms have granted provincial governments specific taxing powers, particularly over PKB and BBNKB, while the central government retains primary authority over major national taxes (

Ahmad, 2002;

Achmad et al., 2022;

Agrawal et al., 2024). Under this arrangement, provincial taxes are expected to be designed in accordance with optimal taxation principles—minimizing economic distortions, preventing harmful tax competition, and balancing horizontal and vertical equity. The quality of tax design and administration at the provincial level thus becomes a critical determinant of both revenue performance and the perceived fairness of the fiscal system.

From a behavioral perspective, taxpayer decisions are strongly shaped by non-economic factors, as described in the Fischer Tax Compliance Model. This model integrates institutional trust, taxpayer attitudes, and perceptions of fairness to explain why individuals comply—or fail to comply—with tax obligations (

Alm, 2019;

Alm & Torgler, 2011;

Freire-Serén & Panadés, 2013).

Marandu et al. (

2015) further highlight the role of administrative effectiveness, suggesting that socialization, inspections, and digital mechanisms not only influence taxpayers’ understanding but also signal fairness and credibility. Likewise, the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) captures perceived integrity of government institutions, which has been shown to affect willingness to comply; when taxpayers perceive corruption, confidence in fiscal fairness declines, reducing incentives to contribute. Thus, administrative capacity and institutional trust interact with economic motives and enforcement mechanisms in shaping provincial tax compliance.

Empirical studies, both domestic and international, have identified a wide range of factors influencing compliance. Internal taxpayer-related determinants include the number of taxpayers and perceptions of fairness and equity (

Inasius, 2019), taxpayer ethics (

Alm & Torgler, 2011), trust in government (

Alm, 2019;

Batrancea et al., 2019;

Da Silva et al., 2019;

Kirchler et al., 2008), behavior and attitudes (

Saad, 2014), and constraints such as lack of knowledge, negative perceptions, and personal financial difficulties (

Christina, 2022;

Fau & Kurniawati, 2022;

Harjowiryono, 2019;

Mpofu & Moloi, 2022;

Saptono et al., 2023). External determinants include audit probability (

Inasius, 2019), socialization cost (

Lalisho, 2019;

Permatasari & Mutoharoh, 2021), system complexity (

Abdu & Adem, 2023;

Pavel & Vítek, 2014;

Saad, 2014), inefficiency of tax authorities (

Abdu & Adem, 2023;

Pavel & Vítek, 2014), high tax rates (

Lalisho, 2019), economic conditions (

Doktoralina & Nugroho, 2010;

Yossinomita et al., 2025), and weaknesses in institutional governance—such as audit delays, transparency issues, arbitrary assessments, and political instability (

Halim & Rahman, 2022;

Manrejo & Yulaeli, 2022;

Meliandari & Utomo, 2022;

Totanan et al., 2024).

Although previous studies provide valuable insights into tax compliance behavior, the existing literature remains fragmented across tax types, regions, and methodological approaches. Most studies rely on primary survey data or examine only specific local governments, limiting their generalizability to the provincial or national level (

Inasius, 2019). Empirical work has also tended to emphasize socialization and audit probability while often omitting collection cost—a key administrative dimension reflecting enforcement intensity, administrative efficiency, and arrears management (

Lalisho, 2019;

Permatasari & Mutoharoh, 2021). Furthermore, institutional indicators such as the Corruption Perception Index and digitalization are rarely integrated alongside administrative and economic variables, despite strong theoretical justification from the Fischer Tax Compliance Model and fiscal federalism perspectives (

Marandu et al., 2015;

Batrancea et al., 2019). Recent evaluations similarly highlight that studies on regional tax compliance seldom adopt a unified analytical framework that incorporates administrative variables, governance quality, and institutional trust (

Saptono et al., 2023;

Totanan et al., 2024;

Biswan, 2022). In addition, spatial dependencies and interprovincial spillovers—widely recognized in the fiscal federalism literature—have rarely been explored in Indonesian contexts, even though neighboring provinces often share administrative practices, institutional characteristics, and similar economic conditions (

Agrawal et al., 2024;

Smoke, 2015). These limitations underscore the need for a comprehensive, data-driven analysis that integrates administrative, institutional, and spatial dimensions of provincial tax compliance using nationwide secondary data.

From a methodological perspective, past studies have generally not employed approaches capable of capturing interprovincial spillover effects. In practice, tax compliance in one province may influence neighboring provinces through administrative diffusion, taxpayer mobility, or shared regional economic conditions. Spatial analysis is therefore important for understanding clustering patterns and the spatial dependency inherent in compliance behavior. At the same time, administrative variables such as socialization, inspection, and collection costs may exhibit correlated disturbances across provinces due to uniform regulations or similar institutional structures. This justifies the use of a SUR–SEM approach, which can estimate multiple related equations while accounting for cross-equation error correlation and theoretically grounded interaction pathways.

These gaps motivate the present study, which examines how socialization costs, inspection costs, collection costs, statutory tax rates, the CPI, and the Indeks Masyarakat Digital Indonesia (IMDI; Indonesian Digital Society Index) influence provincial tax compliance using comprehensive secondary data from all 34 provinces in Indonesia. By integrating spatial regression, Seemingly Unrelated Regression–Structural Equation Modeling (SUR–SEM), and SWOT analysis, this research provides a more holistic understanding of both structural and behavioral drivers of compliance. The use of full provincial coverage enhances external validity, while including collection costs and institutional variables provides a more complete representation of administrative and governance determinants.

Therefore, this study aims to analyze the extent to which administrative costs, tax rate structures, governance quality, and digital readiness affect regional tax compliance in Indonesia. The findings are expected to offer a nuanced understanding of how provincial tax administration functions in practice and to provide evidence-based recommendations for designing more effective and equitable tax policies at the subnational level.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

This study adopts a quantitative, descriptive approach, supported by spatial regression and SUR–SEM analysis, to examine the determinants of regional tax compliance in Indonesia’s provincial governments. The methodological framework aligns with the theoretical foundations of Fiscal Federalism and Tax Optimization Theory, which explain how regional autonomy, administrative capacity, and efficient tax instruments shape revenue performance. The Fischer Tax Compliance Model also provides the behavioral and institutional basis for incorporating variables such as corruption perceptions, the Digital Society Index, socialization activities, inspections, and collection processes.

Methodologically, this study aims to empirically assess how administrative costs, statutory tax rates, institutional conditions, and digital readiness shape provincial tax compliance outcomes across Indonesia. The combination of these quantitative methods enables the study to evaluate both structural and spatial dimensions of provincial tax compliance. At the same time, SWOT analysis is employed to formulate strategic recommendations based on institutional strengths and external opportunities.

2.2. Data and Scope of Study

The analysis uses secondary data from all 34 provinces in Indonesia covering the period 2020–2024, resulting in a balanced dataset representing five years of provincial fiscal administration. The selection of 34 provinces was not based on sampling but on full coverage of the entire population of provincial governments in Indonesia, ensuring comprehensive representation without exclusion. Therefore, all provinces with complete fiscal and administrative data for 2020–2024 were included. The selection of this period reflects recent developments in regional tax management following digital transformations and post-pandemic adjustments in administrative processes.

The types of data used include inspection data, billing/collection data, tax rate data for PKB and BBNKB, CPI, and IMDI. These data were obtained from the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Ministry of Finance, the Badan Pengelola Keuangan dan Pendapatan Daerah (BPKPD; Regional Financial and Asset Management Agency), Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik, BPS; Statistics Indonesia), and the Ministry of Communication and Digital Affairs.

2.3. Operational Definition of Variables

The study defines the key variables as follows:

Tax Compliance (Y) is measured as the ratio of realized revenue to the official target for PKB and BBNKB at the provincial level.

Socialization Cost (X1) refers to annual expenditures allocated for taxpayer education, outreach, and public information campaigns.

Inspection Cost (X2) represents spending on audit, verification, and field inspection activities.

Collection Cost (X3) includes operational expenses related to billing, enforcement, and arrears management.

PKB (X4) is the statutory rate applied to motor vehicle ownership.

BBNKB (X5) is the statutory rate applied to the transfer of motor vehicle ownership.

CPI (X6) reflects the perceived level of corruption in provincial governance structures and is published by BPS.

IMDI (X7) measures digital readiness, access, and behavior at the provincial level.

2.4. Spatial Regression Analysis

Spatial regression is employed to examine geographical patterns of provincial tax compliance and to identify clusters of high or low performance. The analysis uses a Spatial Error Model (SEM) to account for spatially correlated disturbances among adjacent provinces. The spatial structure is based on provincial contiguity, allowing the model to capture interprovincial influences arising from proximity, administrative similarity, or regional economic conditions.

The spatial clustering results—identifying High–High, Low–Low, and Low–High categories—inform the interpretation of compliance disparities across provinces.

2.5. SUR–SEM Specification

To further analyze the determinants of tax compliance, the study applies a SUR–SEM approach. The SUR framework is appropriate because provincial fiscal behavior may exhibit correlated error structures due to uniform regulations, similar administrative environments, or simultaneous changes in fiscal capacity. The SEM structure complements this by enabling the inclusion of multiple variables grounded in taxation theory, allowing the model to reflect the complex interactions outlined in Fiscal Federalism and the Fischer Model.

The SUR–SEM consists of two or more interrelated regression equations. This study assumes two equations for tax compliance in two different regions, simplified as follows:

Description:

| = Local Tax Compliance in Province A; |

| = Local Tax Compliance in Province B; |

| = Constants For Each Region; |

| β1–8 | = Coefficient For The Independent Variable; |

| X1 | = Socialization Cost; |

| X2 | = Inspection Cost; |

| X3 | = Collection Cost; |

| X4 | = PKB; |

| X5 | = BBNKB; |

| X6 | = Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI); |

| X7 | = Digitalization (IMDI); |

| i | = Number of Observations in 34 Provinces in Indonesia; |

| t | = Number of years of research. |

The model is used to test the hypothesis that administrative costs (socialization, inspection, and collection), statutory tax rates (PKB and BBNKB), corruption perception, and digital readiness significantly influence provincial tax compliance.

Standard diagnostic checks were conducted, including tests for multicollinearity, heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and normality to ensure the reliability of the estimated model. Model adequacy was also assessed using Chow, Hausman, and LM tests, along with goodness-of-fit evaluations. Potential issues common to provincial-level secondary data—such as correlated disturbances—were addressed by applying the Spatial Error Model.

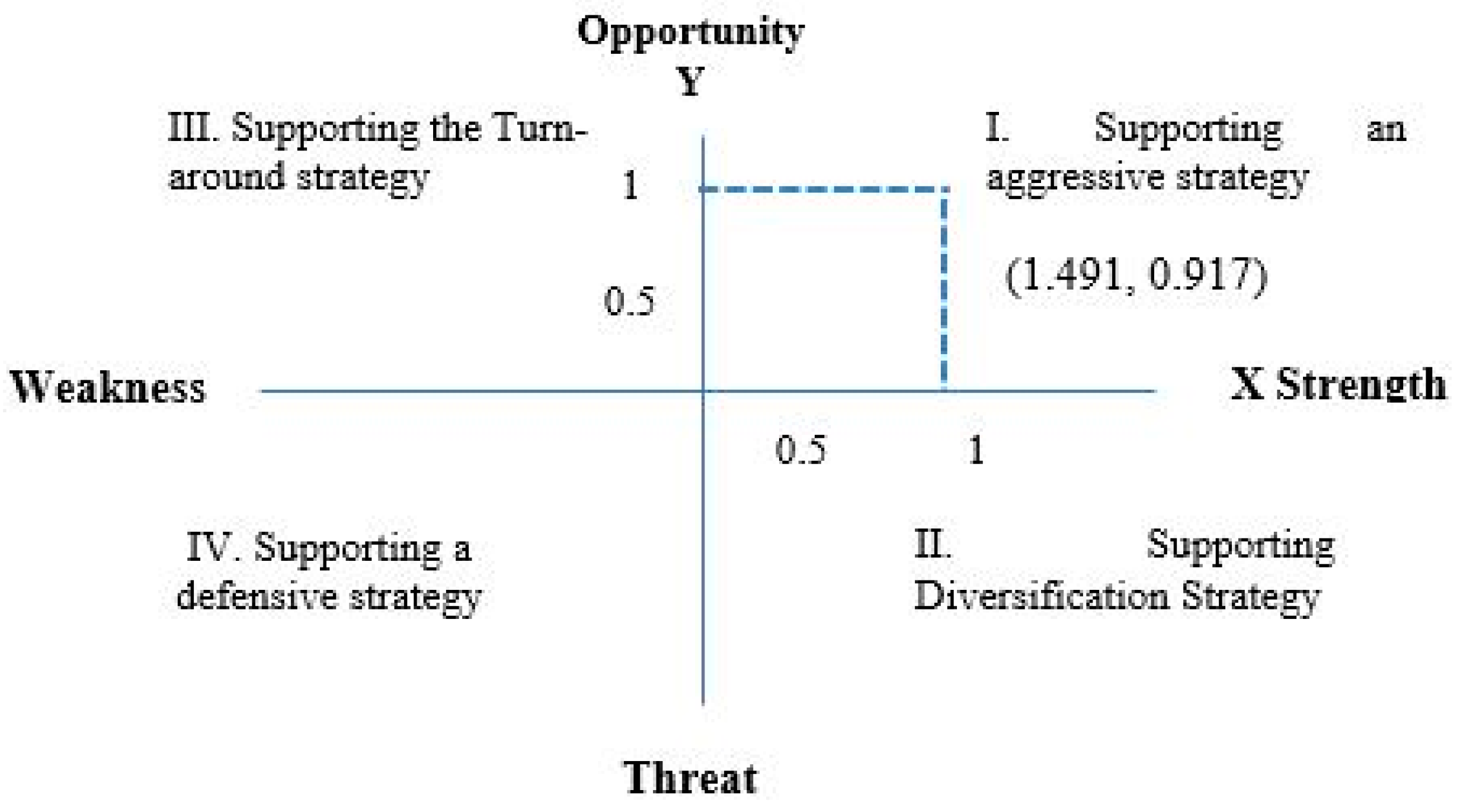

2.6. SWOT and Focus Group Discussion (FGD) for Strategy Formulation

In addition to quantitative methods, this study employs a combined SWOT and Focus Group Discussion (FGD) approach to refine strategic recommendations based on the empirical results. SWOT information was collected through an online questionnaire distributed via Google Form to practitioners and experts from institutions directly involved in regional tax administration, including the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Ministry of Finance, Statistics Indonesia, provincial BPKPD offices, and universities. The questionnaire captured assessments of internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as external opportunities and threats, which were subsequently synthesized into IFAS and EFAS matrices. The resulting position of Indonesia’s provincial tax compliance in Quadrant I indicates strong internal capacity supported by substantial external opportunities, suggesting that aggressive, growth-oriented strategies are appropriate.

To deepen the interpretation of the quantitative findings and ensure that the recommended strategies were grounded in practical administrative realities, an FGD was conducted with purposively selected participants. The group consisted of senior officials and technical staff from the Directorate of Local Taxes and Levies at the Directorate General of Fiscal Balance (Ministry of Finance), the Directorate of Regional Revenue at the Directorate General of Regional Fiscal (Ministry of Home Affairs), Statistics Indonesia, and provincial BPKPD institutions, along with academic experts in public finance. Provinces were selected to represent different spatial compliance patterns—High–High, Low–Low, and Low–High clusters—so that diverse administrative contexts could be incorporated into the discussion.

The FGD was held online using a semi-structured discussion guide based on the preliminary spatial regression results, SUR–SEM outputs, and draft SWOT matrices. Before the session, participants received a concise summary of the empirical findings to ensure that the discussion was informed and analytically focused. During the discussion, participants elaborated on the practical relevance of variables such as socialization costs, inspection costs, collection practices, tax rates, CPI, and digitalization, and provided substantive input regarding the feasibility and priority of potential policy recommendations.

The transcripts were independently reviewed by two researchers, who coded the data and reconciled any differences through consensus. A summary of the discussion was then shared with participants for validation. The findings from the FGD were not used to modify the statistical estimates but to triangulate and contextualize the quantitative results. They also strengthened the formulation of the aggressive strategy indicated by the SWOT analysis, so that the final recommendations are empirically grounded and practically implementable.

3. Results

The mapping method used spatial regression analysis, a statistical technique that determines the relationship between dependent and independent variables while accounting for location. The dependent variable in this study is tax compliance, whereas the independent variables are socialization costs, inspection costs, collection costs, tax rates, the anti-corruption perception index, and digitalization. The research objects are the provinces in Indonesia. Spatial regression analysis was conducted to identify factors influencing tax compliance across Indonesian provinces, accounting for spatial or locational factors. The following subsections present the estimation results related to the spatial regression.

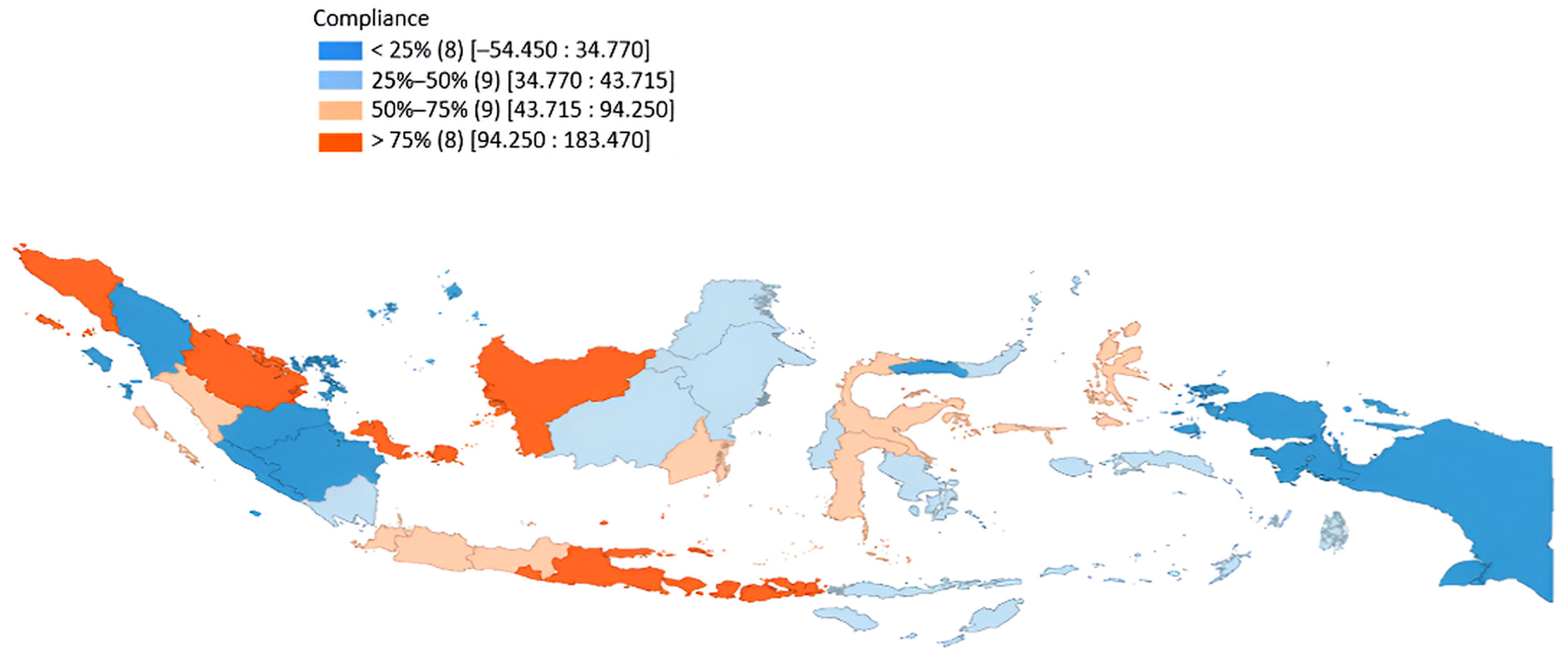

Based on

Figure 1, the tax compliance level in Indonesia is divided into four categories, each defined by percentile values up to 75%. There are no outliers for the dependent variable tax compliance level, allowing the analysis to proceed. The standard multiplier used to identify outliers is 1.5 hinges, or 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR), which is derived from the difference between the upper and lower quartiles. An observed tax compliance value is classified as an outlier if it falls more than the interquartile variation (the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile values) above or below each of these percentile boundaries. The standard multiplier used is 1.5 times the IQR. The following section explains the Box Map interpretation results.

Based on

Table 1, four tax compliance levels in Indonesia can be identified from the quartile distribution. Tax compliance levels in the lowest quartile (<25%) are represented in dark blue and include eight provinces: North Sumatra, Jambi, Bengkulu, South Sumatra, Riau Islands, Gorontalo, West Papua, and Papua. Tax compliance levels below the median (25–50%), shown in light blue, are represented by nine provinces: Lampung, West Kalimantan, East Kalimantan, North Kalimantan, West Sulawesi, North Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi, Maluku, and East Nusa Tenggara. Tax compliance levels between the median (50%) and the upper quartile (75%), represented in pink, include nine provinces: West Sumatra, Banten, West Java, Central Java, South Kalimantan, Central Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, North Maluku, and Jakarta. Finally, tax compliance levels above the highest quartile (>75%) are shown in orange. They are found in eight provinces: Aceh, Riau, Bangka Belitung, Central Kalimantan, East Java, Bali, West Nusa Tenggara, and Yogyakarta.

3.1. The Measure of Inequality

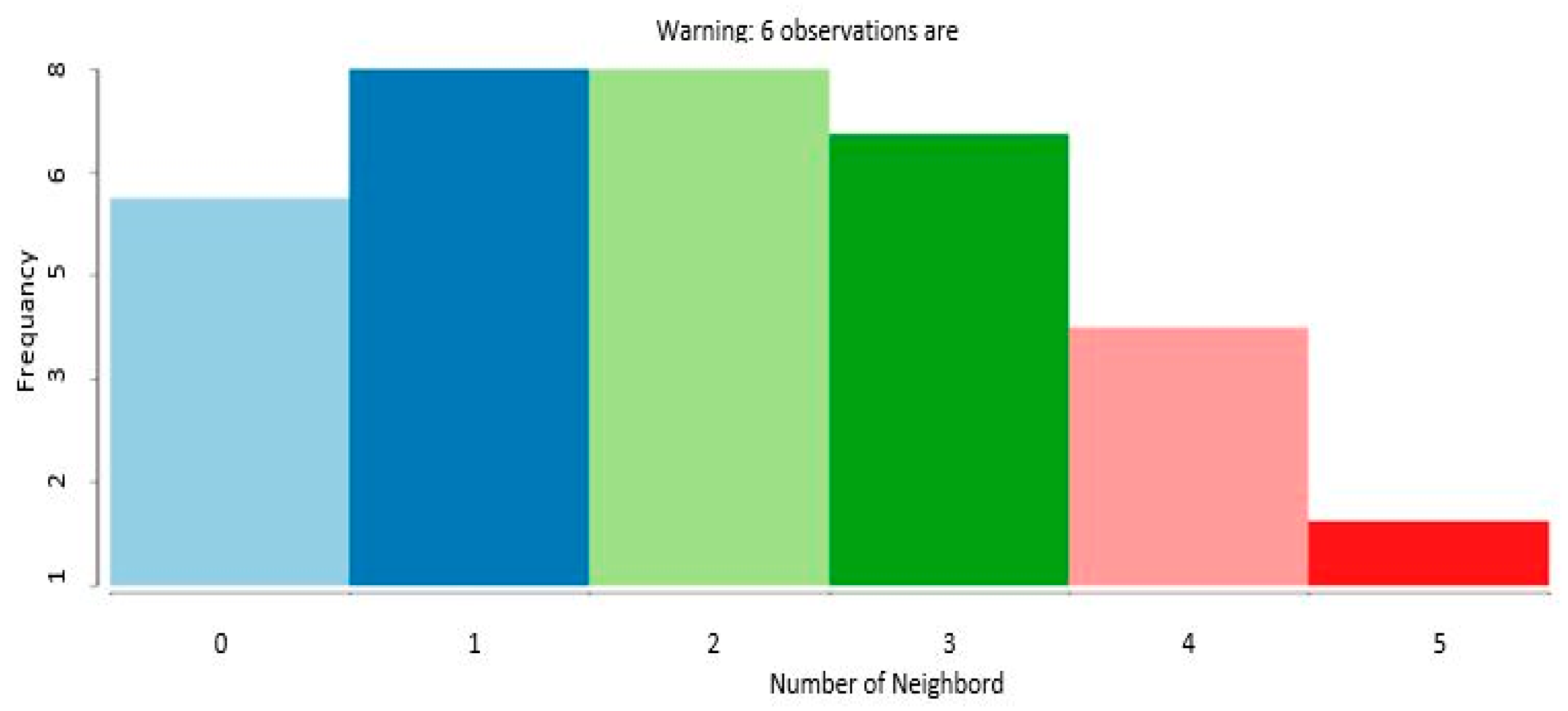

The measure of inequality viewed from a spatial-weight perspective is a step toward understanding the neighborhood relationships between regions. The number of neighbors for the provinces of Indonesia is calculated using the queen contiguity rule. Queen contiguity is a method of determining neighboring units by identifying provinces that share either sides or corners of their administrative boundaries. The following figure presents a histogram of the number of neighboring provinces for Indonesia.

Based on

Figure 2 and

Table 2, the number of neighboring provinces in Indonesia varies. The x-axis shows the number of neighbors, while the y-axis shows the frequency or the number of provinces that have a specific number of neighbors. The maximum number of neighbors is 6, and the minimum is 0. For example, the orange color indicates that eight provinces have six neighbors, and similar interpretations apply to the other colors. The distribution of neighboring provinces ranges from 0 to 5. Light blue represents provinces with zero neighbors, which are the provinces with the fewest neighbors; for instance, Bali has only one neighbor, West Nusa Tenggara. Meanwhile, the highest number of neighbors is represented in red, with five neighbors, found in Central Java, which borders West Java, East Java, Yogyakarta, Banten, and South Sumatra.

3.2. Tax Compliance Mapping

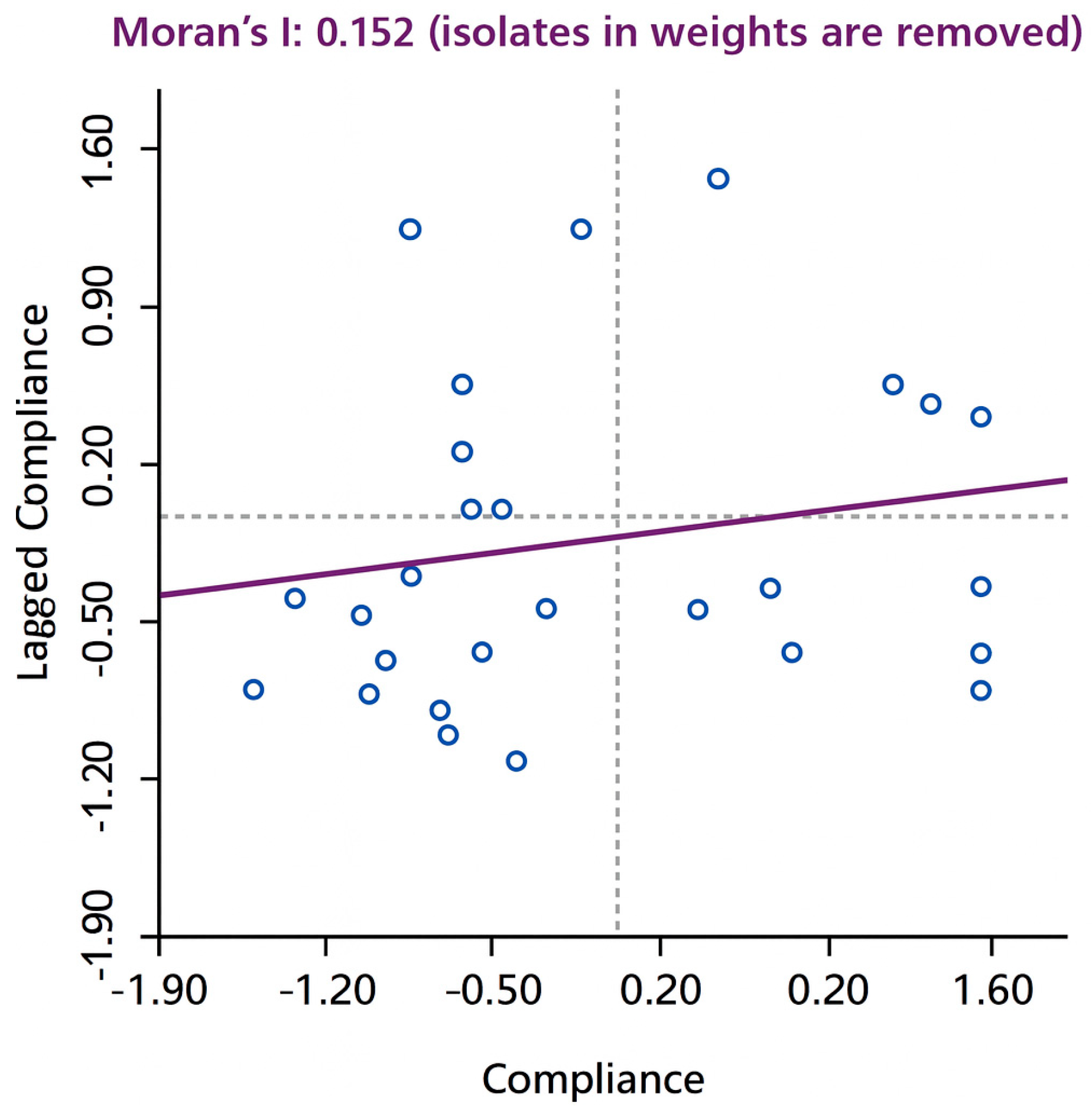

Mapping is carried out using spatial autocorrelation, a spatial data analysis technique that examines the influence of spatial relationships among tax compliance values across provinces in Indonesia. Autocorrelation is analyzed using Moran’s Index and the Local Indicator of Spatial Association (LISA). Moran’s Index describes global spatial autocorrelation, whereas LISA identifies local patterns. The following figures present the results of the spatial autocorrelation test.

According to

Figure 3, Moran’s Index is 0.15, indicating a value approaching 1. A Moran’s Index closer to 1 suggests the presence of spatial autocorrelation in the tax compliance values across Indonesian provinces. The slope of the line in

Figure 4 also shows that the distribution of Moran’s Index values clusters in quadrants I and III. Quadrant I indicates positive autocorrelation, where provinces with high tax compliance cluster with other high-compliance provinces (high–high). Conversely, quadrant III indicates negative autocorrelation, where provinces with low compliance cluster with other low-compliance provinces (low–low).

Based on the significance map in

Figure 5, four provinces are identified as significant. This indicates the presence of spatial autocorrelation or a relationship between the tax compliance levels in these provinces and those of their nearest neighbors. These relationships form the following groups.

Figure 5 presents the LISA Cluster Map generated with GeoDa. Three groups of provinces are visible in Indonesia: High–High, Low–Low, and Low–High The map in indicates that the level of tax compliance across Indonesian provinces is spatially influenced. Provinces with high tax compliance, shown in red, are surrounded by other provinces with high compliance levels. Meanwhile, provinces with low compliance levels, shown in blue, are surrounded by provinces with similarly low compliance. The gray areas on the LISA map represent provinces that are not significant because their tax compliance levels are randomly distributed. These LISA cluster map results can be used as a reference for implementing programs to improve tax compliance in Indonesia, as they help identify provinces that should be prioritized for intervention.

3.3. Spatial Error Regression Model

The spatial error regression model obtained in this research is constructed by modeling the independent variables that are related to the dependent variable, namely the tax compliance rate. To understand the spatial modeling of tax compliance in Indonesian provinces, the GeoDa application is used with the following data inputs.

Before estimating the spatial error model, standard diagnostic checks were performed to ensure the robustness of the analysis. Tests for multicollinearity, heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and normality indicated that the data met the required econometric assumptions. In addition, model adequacy tests—such as Chow, Hausman, and Lagrange Multiplier evaluations—confirmed the suitability of the chosen model specification. The presence of spatially correlated disturbances was also validated, supporting the use of the Spatial Error Model.

Table 3 shows that three independent variables are significant at the 0.10% level: Socialization Costs (X1), PKB (X4), and BBNKB (X5). The significant lambda value also indicates the existence of regional correlation in tax compliance among provinces in Indonesia. The spatial error regression model uses the following equation:

The spatial error regression model can be interpreted as follows. The influence of socialization costs on tax compliance is the same across provinces, with an elasticity of 3.83786. This means that if socialization costs in a province increase by one million rupiah, tax compliance will increase by 3.83%. The effect of the PKB tax rate on tax compliance is the same for each province, with an elasticity of 2.58076, meaning that if the PKB tax rate increases by one percent, tax compliance will increase by 2.58%. The effect of the BBNKB tax rate on tax compliance is the same for each province, with an elasticity of −9.261122, meaning that if the BBNKB tax rate increases by one percent, tax compliance will decrease by 9.26%. Meanwhile, the variables for inspection costs, collection costs (X3), CPI (X6), and IMDI (X7) do not affect tax compliance.

3.4. Model Goodness Test

The goodness-of-fit test in this study is conducted by comparing Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and R-squared values. The results of the goodness-of-fit test for the Spatial Autoregressive Model and the Spatial Error Model are presented below:

Table 4 shows that the Spatial Error Model performs better than the Spatial Autoregressive Model, as indicated by its lower AIC and higher R-squared. The goodness-of-fit results for the Spatial Error Model indicate an AIC of 942.625 and an R-squared of 85.02%. The R-squared value indicates that the variables of socialization costs, inspection costs, collection costs, PKB rates, BBNKB rates, the corruption perception index, and digitalization jointly explain 85.02% of the variation in tax compliance across Indonesian provinces. Other variables influence the remaining 14.98%.

3.5. Strategy for Improving Tax Compliance in Regional Taxes of Provinces in Indonesia

Improving local tax compliance across Indonesia’s provinces requires a comprehensive approach. One method for determining the main strategy is through a SWOT analysis, which evaluates efforts to increase public awareness regarding the importance of taxes. SWOT consists of Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats, organized systematically and typically presented in a simple grid format. The following section presents the SWOT analysis used to examine strategies for improving local tax compliance in Indonesian provinces.

Table 5 presents the Internal Factors Analysis Strategy.

After completing the internal factor analysis, the next step is to conduct the external factor analysis presented in

Table 6.

After assigning weights and ratings to internal and external factors, alternative strategies are formulated using the SWOT matrix. The SWOT matrix is shown in

Table 7.

Following the calculation of IFAS and EFAS indicator weights, the next step is to determine the strategic alternatives by identifying the quadrant position in the SWOT analysis diagram. Determining the coordinates of the SWOT diagram helps identify the strategic position of tax compliance improvement, whether in quadrant I, II, III, or IV. This classification helps determine whether the strategy is Aggressive, Diversification, Turnaround, or Defensive. The diagram illustrating the strategic position of tax compliance improvement for provincial taxes in Indonesia is presented in

Figure 6.

Based on

Figure 6, the strategic position for improving tax compliance in provincial taxes in Indonesia falls in quadrant I, which indicates an Aggressive Strategy. This quadrant represents the most favorable situation, as the government possesses both strengths and opportunities. Under these conditions, the recommended approach is to support aggressive, growth-oriented policies by utilizing available opportunities and internal strengths. The aggressive strategy aims to increase the number of taxpayers and expand tax revenue by accepting greater strategic risk.

The aggressive growth strategy reflects the government’s internal strengths, which can be used to capitalize on existing opportunities, thereby potentially increasing local tax compliance in Indonesia. According to

Rangkuti (

2015), quadrant I represents a highly optimal situation. The government possesses numerous strengths and opportunities and is therefore well-positioned to take advantage of favorable conditions. The recommended approach is to adopt an aggressive growth-oriented strategy.

The strategy for increasing tax compliance in provincial taxes in Indonesia should employ an S–O (Strengths–Opportunities) approach, combining the strengths of taxpayers and government institutions with opportunities in the external environment. Based on the SWOT analysis, the S–O strategies include using a digital tax reporting system to support interactive outreach programs that enhance public trust in the government; developing digital-based applications that educate the public about tax obligations and thereby strengthen tax compliance; and utilizing consistent and transparent policies to simplify tax procedures and attract more taxpayers.

Thus, based on the S–O strategy for improving tax compliance in regional taxes across Indonesia, the position falls within quadrant I of the SWOT diagram, indicating a highly favorable condition. The government possesses both strengths and opportunities and can therefore capitalize on existing opportunities. Through this analysis, the government can leverage its internal strengths while simultaneously identifying external opportunities, despite weaknesses and threats. The strategy for increasing tax compliance in Indonesia’s provinces can thus be implemented through the S–O approach consisting of three main steps: using a digital system for tax reporting to conduct interactive socialization programs that facilitate tax reporting and payment, thereby increasing transparency and public trust; developing digital-based applications that provide information on tax obligations and educate the public about the importance of taxes, thereby encouraging compliance; and applying consistent and transparent tax policies while simplifying tax procedures to attract more taxpayers. By implementing these strategies, the government can demonstrate that improving tax compliance aligns with the characteristics of quadrant I, effectively utilizing strengths and opportunities to create a more efficient and responsive regional tax system.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Socialization Costs on Tax Compliance in Regional Taxes of Provinces in Indonesia

The results show that socialization costs have a significant positive effect on provincial tax compliance. This relationship is theoretically consistent with the Fischer Tax Compliance Model, which emphasizes that taxpayers’ knowledge, understanding of procedures, and perceptions of fairness are central behavioral determinants of compliance. Increased socialization activities—through education programs, public campaigns, and digital outreach—reduce informational asymmetries and help taxpayers better understand their obligations, thereby lowering the psychological and procedural barriers that commonly lead to non-compliance.

This mechanism is reinforced by deterrence theory, which suggests that when taxpayers are better informed about rules, deadlines, and potential sanctions, their perceived probability of detection increases, strengthening voluntary compliance even in the absence of additional audits. The findings align with earlier studies by

Ersania and Merkusiwati (

2018), who highlight the importance of sustained and accessible tax socialization in shaping taxpayer behavior, and by

Kristina and Janrosl (

2022), who demonstrate that improved tax knowledge significantly enhances motor vehicle taxpayer compliance. Similarly,

Lalisho (

2019) and

Wardani and Wati (

2018) show that limited taxpayer knowledge—often due to inadequate socialization—contributes to persistent non-compliance.

Insights from the FGD further support this mechanism. Participants noted that in many provinces, especially outside major urban areas, non-compliance often stems from a lack of understanding rather than deliberate evasion. Respondents highlighted issues such as “confusion about online payment procedures” and “limited access to reliable information,” underscoring the importance of well-targeted socialization. Provinces that shifted from traditional outreach to digital campaigns reported substantial improvements in compliance, particularly among younger taxpayers.

This is consistent with

Saad (

2014), who finds that taxpayers frequently perceive the tax system as complex and difficult to navigate, reinforcing the role of socialization in simplifying procedures and improving system usability. However, the result differs from

Wulandari et al. (

2019), who found that socialization did not significantly influence taxpayer awareness. FGD participants offered a possible explanation, noting that socialization efforts are sometimes sporadic, poorly targeted, or conducted merely to meet administrative requirements rather than addressing taxpayers’ actual information needs. This suggests that the effectiveness of socialization depends on its quality, consistency, and delivery approach, providing a coherent explanation for differing empirical findings across studies.

4.2. The Effect of Vehicle Tax Rates on Tax Compliance in Regional Taxes in Provinces in Indonesia

The results show that the statutory PKB rate significantly influences provincial tax compliance. From the perspective of Fiscal Federalism, provinces possess discretion to set PKB rates within national regulatory limits, enabling rate structures to reflect local economic conditions and administrative capacities. When tax rates are calibrated in ways taxpayers perceive as reasonable and proportional to vehicle value, compliance tends to increase because the tax burden is viewed as fair and predictable.

This finding aligns with the tax morale literature, which suggests that taxpayers are more likely to comply when they perceive tax rates as justifiable relative to the public services they receive. Excessive rates, by contrast, may encourage avoidance or strategic delay, consistent with deterrence theory, which posits that taxpayers weigh perceived costs against expected enforcement outcomes. If rates are perceived as burdensome, the incentive to underreport or delay payment increases unless the perceived probability of detection is high.

The empirical pattern observed in this study is consistent with prior findings.

Pavel and Vítek (

2014) demonstrate that tax system complexity and regulatory burdens influence compliance behavior. Similarly,

Lalisho (

2019) shows that high tax rates contribute to non-compliance when taxpayers anticipate higher future costs.

Vincent (

2023) emphasizes that subnational tax administration and discretionary authority affect compliance outcomes, especially when enforcement varies across jurisdictions. These studies help explain why PKB rates significantly affect compliance: taxpayers are sensitive to the trade-off between tax burden and administrative fairness.

Further evidence comes from

Yu (

2023), who finds that tax systems that rely more heavily on direct taxes tend to exhibit higher compliance. PKB, as a direct tax on vehicle ownership, fits this pattern, indicating that rate design plays a broader structural role.

Cahyani and Noviari (

2019) and

Sandra and Chandra (

2021) also report that rational and transparent rates positively affect taxpayer compliance, particularly when rate reductions or incentives help ease the taxpayer burden.

FGD insights clarify this mechanism. Respondents noted that PKB compliance increases when rate adjustments are accompanied by improved service delivery, especially through digital systems that simplify payment. Several provinces reported significant increases in compliance after streamlining renewal procedures or offering limited-time rate incentives. Conversely, respondents cautioned that when rate increases are implemented without adequate communication or system improvements, compliance tends to decline. This suggests that tax rates’ effectiveness depends not only on their nominal levels but also on administrative capacity and taxpayer perceptions of fairness.

However, this study’s findings differ from

Zulma (

2020), who reported no significant relationship between tax rates and compliance during periods of temporary tax relief. This discrepancy may be explained by exogenous shocks—such as economic downturns—when policymakers introduce rate reductions or exemptions. In such situations, taxpayer behavior may be driven more by economic constraints than by rate structures alone, a point also noted by several FGD participants when discussing delays in PKB payments during the pandemic.

4.3. The Effect of BBNKB Rates on Tax Compliance in Regional Taxes in Provinces in Indonesia

The results show that BBNKB rates significantly influence provincial tax compliance. This relationship can be explained through the lens of fiscal federalism, in which provinces exercise discretion in setting tax rates for vehicle ownership transfers. Because BBNKB is paid at the moment of property transfer, taxpayers’ compliance decisions are sensitive to how burdensome or proportional the rate is relative to the transaction value. Reasonable and transparent rates enhance the perceived fairness of the tax system, whereas excessively high rates may discourage formal registration and lead to avoidance behavior.

From a behavioral perspective, this finding aligns with deterrence theory and the tax morale framework. High BBNKB rates may create incentives for taxpayers to delay or avoid reporting ownership changes unless enforcement is strong or the expected benefits of compliance outweigh the costs. Conversely, moderate or incentive-based rates can foster voluntary compliance by reducing the perceived burden and signaling administrative fairness. This is consistent with

Lalisho (

2019), who notes that high tax burdens increase the risk of non-compliance, and with

Pavel and Vítek (

2014), who highlight that tax system complexity and perceived burdens affect compliance behavior.

The role of administrative discretion is further supported by

Vincent (

2023), who shows that subnational tax rights and administrative practices significantly shape taxpayer responses. Provinces with more efficient service systems—particularly those that digitize ownership transfer procedures—tend to experience higher BBNKB compliance even when rates remain constant. This suggests that tax rates interact with administrative capacity, service quality, and taxpayers’ perceptions of regulatory efficiency.

FGD insights reinforce this mechanism. Several provincial officials indicated that BBNKB non-compliance often arises from high transaction costs associated with administrative processes, including long waiting times, limited digital service options, or inconsistent documentation requirements. Respondents noted that taxpayers frequently postpone official ownership transfers when procedures are viewed as cumbersome or costly. Provinces that introduced online registration systems or collaborated with vehicle dealerships reported substantial improvements in compliance, indicating that administrative convenience moderates the effect of the tax rate.

The empirical findings also align with broader research showing that reliance on direct taxes (including property and transaction taxes) tends to increase compliance when rates are predictable and perceived as fair, as noted by

Yu (

2023). Similarly,

Cahyani and Noviari (

2019) and

Sandra and Chandra (

2021) found that rate adjustments—such as reductions or temporary relief—can improve compliance by easing the burden on taxpayers.

However, the findings differ from

Zulma (

2020), who reported no significant effect of tax rates on compliance during periods of widespread tax relief under abnormal economic conditions. This suggests that the influence of BBNKB rates is contingent on broader macroeconomic factors and policy environments. When extraordinary relief measures or economic shocks dominate taxpayer decision-making, variations in rates may have a weaker effect on compliance.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of provincial tax compliance in Indonesia, integrating spatial analysis, SUR–SEM, and SWOT evaluation using complete secondary data from 34 provinces. The empirical results show that tax compliance is not uniformly distributed across Indonesia, with significant spatial clustering occurring in only four provinces. Central Java exhibits a High–High spatial interaction pattern, South Sumatra and Lampung fall into the Low–Low cluster, and North Sumatra shows a Low–High pattern. These findings confirm that compliance behavior is influenced not only by local administrative performance but also by the dynamics of neighboring provinces.

The SUR–SEM analysis identifies socialization costs, motor vehicle tax (PKB) rates, and vehicle transfer tax (BBNKB) rates as significant determinants of provincial tax compliance. These results align with the Fischer Tax Compliance Model, indicating that effective communication, credible enforcement signals, and perceptions of fairness in rate setting are central behavioral drivers of compliance. The significance of PKB and BBNKB rates also reflects the importance of tax design under fiscal federalism, where provincial tax instruments must balance revenue needs with taxpayers’ perceptions of equity.

The SWOT analysis positions the provincial tax administration in Quadrant I, indicating strong internal capacity and substantial external opportunities to improve compliance. This suggests that the government is well-positioned to adopt an Aggressive Strategy—expanding digital services, strengthening enforcement mechanisms, and designing more transparent and equitable tax schemes. Operationalizing this strategy requires targeted investments in taxpayer education, digital payment systems, audit consistency, and improved arrears management, particularly in provinces with persistently low compliance.

These findings provide actionable guidance for provincial governments. Increasing the effectiveness of socialization through digital platforms can improve taxpayer literacy and voluntary compliance at relatively low cost. In addition, optimizing PKB and BBNKB rate structures can enhance revenue without imposing undue economic burdens, provided that rate adjustments are transparent and accompanied by visible improvements in public service delivery. The spatial results also indicate that provinces should coordinate with neighboring regions to harmonize administrative practices and share innovations in tax governance.

This study is constrained by the limited availability of disaggregated administrative data, particularly regarding taxpayer income, vehicle ownership characteristics, and behavioral indicators. Data collection remains challenging because many provincial records are stored offline. Future research should incorporate micro-level taxpayer data, examine compliance determinants using longitudinal models, and extend spatial analysis to include inter-district spillovers. Comparative studies across countries with similar decentralized tax systems may also enhance generalizability and provide broader policy insights.