1. Introducition

South Africa’s macroeconomic transformation has significantly influenced its financial and policy landscape. The performance of stock market sectors offers a critical lens through which to assess economic conditions and investor sentiment. In South Africa, the stock market is composed of diverse sectors, including industrial, financial, and resource-based industries. Each responds differently to shifts in the macroeconomic environment (

Boug et al., 2023). These sectoral dynamics are especially important in a policy-sensitive economy where both monetary and fiscal decisions significantly influence capital flows and investor behaviour. A major turning point in South Africa’s macroeconomic policy framework occurred in February 2002 with the adoption of an inflation-targeting (IT) regime. A key milestone in this transformation was the adoption of the IT regime in 2002, which sought to stabilise inflation within a 3% to 6% range. This marked a shift in the country’s monetary policy framework and had far-reaching implications for sectoral performance in the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE).

Despite the adoption of IT, South Africa continues to grapple with structural challenges such as high unemployment and inequality. While the financial sector has consistently outperformed, its capital-intensive structure limits its role in addressing unemployment. In contrast, labour-intensive sectors, such as manufacturing and mining, remain underdeveloped and highly sensitive to macroeconomic policy changes. Over the past three decades, the South African economy has undergone considerable structural transformation. The services sector has expanded significantly, accounting for 62.6% of GDP in 2022, up from 51.3% in 1990, largely driven by finance, real estate, and transport. Conversely, the industrial sector’s share of GDP declined from 36% in 1990 to approximately 25% in 2023, with manufacturing falling sharply from 24% to just 12% over the same period (

African Development Bank, 2024). This decline in manufacturing, a traditionally labour-intensive sector, has critical implications for employment and long-term growth. Notwithstanding a market capitalisation of 313.48% of GDP in 2020, far surpassing its regional peers, South Africa’s stock market has had limited success in alleviating poverty, unemployment, and inequality. This concern, underscored in the National Treasury’s 2019–2024 Medium-Term Strategic Framework, calls for a critical examination of whether macroeconomic policy can stimulate more inclusive sectoral growth, particularly in labour-absorbing industries.

Historically, South Africa employed various monetary policy frameworks, including exchange-rate targeting, monetary-aggregate targeting, and discretionary approaches, between 1960 and 1998 (

Wolassa, 2015;

Rossouw, 2007). These frameworks failed to stabilise inflation, which remained volatile and adversely affected economic performance. The IT regime was introduced to anchor inflation expectations and enhance macroeconomic stability (

Cheteni et al., 2025). However, the extent to which this regime shift has influenced sectoral stock market responses to macroeconomic policy remains insufficiently explored in the literature. While monetary policy primarily affects liquidity and investment decisions, fiscal policy has implications for corporate profitability and macroeconomic expectations. Their combined effect on sectoral stock performance, especially across policy regimes, warrants closer investigation.

This study investigates the sectoral responses to monetary and fiscal policy shifts across two distinct macroeconomic regimes in South Africa: the pre-IT and IT periods. By analysing sector-specific reactions in bullish and bearish market conditions using a Markov Switching Dynamic Regression (MS-DR) model, we aim to enhance understanding of how structural policy reforms influence sectoral outcomes and, ultimately, inclusive economic development. Specifically, this study addresses the following research objectives: (i) to examine how South Africa’s monetary and fiscal policies have influenced the performance of different stock market sectors, including industrial, financial, and resource-based sectors; (ii) to evaluate the impact of the 2002 transition to the IT regime on sectoral stock market dynamics; and (iii) to assess whether monetary and fiscal policies affect sectoral stock returns differently during bullish and bearish market conditions.

2. Literature Review

The impact of monetary and fiscal policies on financial markets has been widely explored through both theoretical and empirical lenses. Theoretical models such as the IS-LM framework, Tobin’s Q theory, Efficient market hypothesis (EMH), Adaptive Market Hypothesis (AMH) and the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) provide insights into how interest rates, liquidity, and fiscal balances influence investment decisions and asset pricing.

The IS-LM framework provides a foundational tool for analysing interactions between real and monetary sectors. Monetary contraction reduces money supply (M), raising the real interest rate (r

i), suppressing investment (I), lowering output (Y), and potentially depressing stock prices (

Mishkin, 2001):

In open economies, the Mundell-Fleming model incorporates trade and capital flows. Under flexible exchange rates, expansionary monetary policy lowers domestic rates, induces capital outflows, depreciates the currency, and stimulates net exports, supporting stock market performance, particularly in export-oriented sectors. However, assumptions of perfect capital mobility, rational expectations, and homogeneous investors are often violated in South Africa due to structural dualities, risk premiums, and fiscal constraints, motivating regime-sensitive approaches like Markov Switching models.

Tobin’s q theory (

Tobin, 1969) links investment to the ratio of market value of capital (V) to replacement cost (K): q = V/K. Monetary policy influences q via interest rates and liquidity—lower rates increase the present value of future earnings and equity prices (Δq∝-Δr)—while fiscal policy affects q through government spending and taxation (Δq∝-ΔG) (

Plantin & Acharya, 2018). Both policies shape investment and stock market dynamics via their effects on q.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), articulated by

Fama (

1970,

1991), posits that asset prices fully incorporate all available information, making it impossible to consistently achieve abnormal returns through trading on public or private data. Under the semi-strong form, prices adjust rapidly to publicly available information, while the strong form assumes even insider knowledge is reflected in prices. Consequently, both monetary and fiscal policies, such as interest rate changes or government spending adjustments, are generally pre-priced, and only unexpected policy moves generate short-term market volatility (

Baker et al., 2016). Formally, the stock market reaction to interest rates (

r) or fiscal interventions (

G-T) can be expressed as:

where Δ

S represents equity price changes,

β and

γ capture sensitivity to monetary and fiscal shocks, and

ε is an orthogonal disturbance. In emerging markets like South Africa, slower information diffusion, limited institutional participation, and political risk can prolong policy effects, highlighting deviations from EMH predictions (

Udeorah et al., 2025).

The Adaptive Market Hypothesis (AMH) complements EMH by recognising that market efficiency is dynamic and context-dependent (

Gu, 2013). Investors adapt through learning, experience, and feedback but remain boundedly rational, influenced by sentiment, heuristics, and information asymmetries (

Li, 2022). In South Africa, the transition to IT in 2002 exemplifies these dynamics: investor responses to monetary and fiscal interventions varied across regimes, with sectoral equities—financial, industrial, and resources—displaying distinct sensitivities. Fiscal measures, such as increased spending or tax relief, may boost confidence if credible (

End, 2023) but provoke adverse reactions if deemed inflationary or unsustainable (

Pappa et al., 2024).

AMH also explains asymmetric and non-linear market reactions. Behavioural biases such as herding, overconfidence, and loss aversion, coupled with uneven information access, lead to differing market responses to identical policy shocks (

Khan et al., 2025;

Sibande, 2024) Adaptive learning further shapes outcomes: early IT implementation elicited cautious reactions, whereas subsequent years saw more consistent responses as credibility and predictability improved. These mechanisms justify the use of regime-sensitive econometric approaches, such as Markov Switching and time-varying parameter models, to capture sector-specific, asymmetric, and time-varying effects of policy interventions.

Monetary policy transmits through several channels: interest rate, credit, exchange rate, and asset price channels (

Mishkin, 1996). A rise in interest rates increases the cost of borrowing and reduces consumption and investment, leading to lower stock prices. Conversely, expansionary monetary policy, characterised by lower interest rates and increased money supply, tends to stimulate economic activity and raise asset values.

Asset pricing theories provide frameworks for understanding monetary policy’s impact on stock prices. The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) emphasises the relationship between market risk and expected returns, while the Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT) incorporates multiple economic factors influencing asset returns. The Present Value Model (PVM) illustrates how monetary policy adjustments to interest rates alter the discounted value of future cash flows, affecting stock valuations. However, non-policy factors, such as market sentiment and macroeconomic conditions, also play critical roles in shaping stock market behaviour.

Fiscal policy, depending on its stance and financing, can either stimulate or crowd out private investment. Keynesian economics suggests that government spending boosts aggregate demand and corporate earnings, particularly during recessions (

Deleidi, 2022). However, Ricardian equivalence postulates that consumers may offset government stimulus by saving more in anticipation of future tax burdens (

Saraswati & Wahyudi, 2018).

Empirical studies show mixed results.

Alovokpinhou et al. (

2022) and

Marozva (

2020) found that monetary tightening depresses stock prices, while

Jhabak and Shakdwipee (

2025) observed a positive relationship. On Fiscal policy studies

Jonathan (

2024) finds that fiscal policy exerts a positive direct effect but a negative indirect effect on the stock market in ASEAN-5 countries. Similarly,

Nwakobi et al. (

2020) provide evidence that fiscal policy has mixed effects on stock market development in an emerging West African economy. Given the mixed empirical evidence, this study employs a regime-sensitive approach using the MS-DR model to capture non-linear sectoral responses under changing macroeconomic conditions.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Data

This study employs monthly data from June 1995 to December 2023, sourced from the South African Reserve Bank (SARB), covering three sectoral indices: Industrial (IND), Financial (FIN), and Resources (RE, available from January 1996). The independent variables—money supply (M3), interest rate (IR), government expenditure (GE), tax revenue (TAX), exchange rate (EX), and inflation (proxied by two dummies: DM1 for 3%–6% and DM2 for >6%)—are chosen based on theoretical and empirical evidence of their influence on equity markets. M3 captures liquidity conditions, IR reflects the cost of capital, GE and TAX proxy fiscal interventions, EX measures external competitiveness, and inflation gauges macroeconomic stability and real return erosion (

Marozva, 2020;

Chinzara, 2011). The inflation dummies allow the model to examine market responses under controlled versus excessive inflation.

To assess policy dynamics over time, the sample is divided into pre-inflation targeting (June 1995–January 2002) and inflation-targeting periods (February 2002–December 2023). The study adopts a three-sector classification (FIN, IND, RE) consistent with Johannesburg Stock Exchange practices, balancing analytical depth and statistical robustness while capturing heterogeneous sectoral responses.

The Markov Switching Dynamic Regression (MS-DR) framework, with two regimes representing bullish and bearish macro-financial conditions, is applied to identify non-linear and regime-dependent effects. This approach allows the study to evaluate sector-specific responses to monetary and fiscal policy shocks, incorporating recent economic episodes, including the global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and post-pandemic adjustments. The construction of inflation dummies tied to the inflation-targeting band provides a novel lens to assess investor sentiment and market reactions to credible versus excessive inflation, enhancing the understanding of policy transmission mechanisms in South Africa.

3.2. Transformation and Stationarity

All variables were converted to first-differenced logarithmic form to ensure stationarity and facilitate growth rate interpretation. The Zivot–Andrews test was used to confirm unit root behaviour and identify structural breaks, aligning with known macroeconomic events.

3.3. Econometric Model: Markov Switching Dynamic Regression (MS-DR)

In a MS-DR model, dependent variable is modelled with the inclusion of latent regimes that influence the relationship between the dependent and independent variables. These regimes follow a Markov process, that is, the future state depends only on the present state, not the entire past. The MS-DR model is ideal for capturing both linear and non-linear dynamics in the relationship between macroeconomic factors and stock market returns, while also accommodating potential structural breaks. In the MS-DR framework, the model assumes that the economy (and consequently the stock market) switches between different regimes, which are typically unobserved. In this context, these regimes can be interpreted as bullish and bearish. By modelling these market conditions as different regimes, the MS-DR framework allows the relationship between stock market performance and macroeconomic variables to vary depending on whether the market is in a bullish or bearish state. This approach is particularly relevant for understanding the non-linear effects of monetary and fiscal policies on stock markets, as such policies may have very different impacts depending on the prevailing market conditions. The MS-DR model enables the identification of distinct market regimes and allows for regime-dependent coefficients. The regime transition is governed by a first-order Markov process, estimated using maximum likelihood via

Hamilton’s (

1989) filter. Smoothed and filtered probabilities are calculated to determine state classification.

The general form of the Markov Switching Dynamic Regression (MSDR) model is

= Dependent variable (Stock market Index).

= Explanatory variables (IR, TAX, M3, PD, GE, INF, EX).

= Unobserved regime at time t, governed by a Markov process.

= Regime-specific intercept.

= Regime-specific coefficients for explanatory variables.

) = regime-specific error term variance.

Regimes evolve according to a first-order Markov process:

where

represents the probability that the process moves from regime

i at time

t − 1 to regime

j at time

t.

where each row sums to 1:

.

This matrix determines the persistence of regimes:

If and are high, the regimes are persistent. If off-diagonal elements and are large, frequent switching occurs.

The model is estimated using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), typically via

Hamilton’s (

1989) filter. The filtered probabilities

give the probability of being in regime

j at time

t based on data up to

t.The smoothed probabilities

incorporate the entire sample to estimate the most likely regime for each period. Using the estimated transition probabilities and the likelihood function, we compute the steady-state probabilities (long-run probabilities of each regime):

where

π is the stationary distribution of the Markov chain.

4. Theory

The Markov Switching Dynamic Regression (MSDR) model extends traditional approaches by capturing structural breaks and nonlinearities in the relationship between macroeconomic variables and sectoral performance. It recognises that economic conditions alternate between regimes—such as expansion and contraction—where policy instruments have state-dependent effects. This regime dependency is highly relevant in South Africa, where frequent policy shifts and external shocks, including the transition to inflation targeting, challenge linear frameworks.

Earlier studies using ARDL (

Erer & Erer, 2022;

Cobbinah et al., 2024), SVAR (

Hu et al., 2018), and panel VAR (

Zhou & Zhang, 2024) provide important insights but assume linear, time-invariant relationships. Such models are limited in contexts where monetary and fiscal interactions evolve across regimes. Even volatility-focused methods like EGARCH cannot capture regime-dependent parameter shifts.

MSDR overcomes these limitations by allowing parameters to vary endogenously across unobserved regimes, without requiring exogenous break dates. This flexibility enables it to reflect South Africa’s dynamic policy environment, including the inflation-targeting era, the global financial crisis, and COVID-19. Thus, MSDR offers a more robust and theoretically consistent framework for analysing regime-dependent interactions between fiscal policy, monetary policy, and stock market performance.

To ensure stationarity and eliminate distortions arising from scale differences, all variables in this study are expressed in their first differences. This approach, which effectively transforms the data into growth rates, allows the analysis to concentrate on short-run, regime-dependent dynamics while preserving the statistical stability of the model. By employing logarithmic differencing, the study captures proportional rather than absolute changes, thereby enhancing the interpretability of results within an economic framework (

Ogun, 2021). This transformation is particularly appropriate in the context of macroeconomic and financial time series, where variables commonly exhibit unit roots and are non-stationary in levels (

Nasir & Morgan, 2025;

Ryan et al., 2025). Differencing such series mitigates the risk of spurious regression and improves the robustness of econometric inference (

Müller & Watson, 2024). Furthermore, analysing growth rates is consistent with economic theory and practice, as policymakers and researchers are generally more concerned with percentage changes in aggregates such as output, inflation, and monetary supply than with their absolute levels (

Ogun, 2021). Thus, the use of first-differenced logarithmic transformations offers a methodologically sound and theoretically grounded framework for investigating the short-run interplay between monetary and fiscal policies across distinct policy regimes.

5. Results

5.1. Pre-Inflation Targeting Regime

In bullish states, interest rate hikes significantly reduced sectoral performance, especially in the financial sector. Government spending and money supply growth had mixed effects—positive for resources and financials, but negative or insignificant for industrials. The exchange rate exhibited a stabilising effect, with depreciation supporting industrial output.

In bearish states, the policy transmission weakened. Most fiscal and monetary variables lost significance, highlighting reduced policy efficacy during downturns. However, exchange rate effects remained relevant, underscoring the external sector’s role as a buffer.

5.2. Inflation Targeting Regime

The IT regime showed altered dynamics. In bullish periods, higher interest rates surprisingly boosted industrial and resource performance, possibly due to enhanced macroeconomic credibility. Money supply positively impacted financials, while the exchange rate depreciations supported all sectors.

In bearish regimes, the industrial and financial sectors exhibited reduced responsiveness to interest rate movements, but the resource sector remained highly sensitive. Fiscal policy regained significance, with government expenditure supporting the resource index.

5.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics shown in

Table 1 reveal significant differences between the pre-inflation targeting (Pre-IT) and inflation targeting (IT) regimes across key macroeconomic and financial variables. The transition to the inflation-targeting (IT) regime saw notable macroeconomic shifts. The mean interest rate declined from 18% to 10.65%, with lower volatility, indicating a more stable monetary environment. Government expenditure surged from ZAR 17,408 million to ZAR 87,420.71 million, while inflation decreased from 7% to 5.57%, reflecting improved price stability. Money supply expanded significantly, with M3 rising from ZAR 434,545 million to ZAR 2,529,853.25 million, alongside substantial growth in financial (FIN) and resource (RE) indices. Tax revenue increased sharply from ZAR 15,346 million to ZAR 71,673.25 million, aligning with economic expansion. Stock market indices also saw significant gains, with the All-Share Index (ALL) and Industrial Index (IND) increasing from 6969 to 39,604.24 and 5801 to 30,715.65, respectively. The exchange rate remained relatively stable, with a slight decline in the mean from 115 to 108.94, suggesting reduced volatility under the IT regime.

5.2.2. Stationarity

The Zivot–Andrews’s test confirms that all transformed variables (first differences in natural logs) are stationary at levels, with structural breaks corresponding to key economic events as shown by

Table 2. For instance, breaks around 2000–2001, when South Africa was preparing the introduction of the IT regime, reflect fiscal policy adjustments and macroeconomic reforms, while the 2020 break aligns with disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. These regime shifts justify the use of Markov Switching Dynamic Regression (MSDR), which can capture the non-linear, state-dependent dynamics that standard models overlook, thereby providing a more accurate analysis of how fiscal, monetary, and financial factors interact under different policy environments.

5.2.3. Markov Switching Dynamic Regression Pre-Inflation Targeting Regime

The Effect of Monetary and Fiscal Policy Variables on the Industrial Index Pre-Inflation Targeting Period

In the Pre-Inflation Targeting Period, the Bullish Regime (State 1) reveals strong monetary policy transmission as shown on

Table 3, with higher DLIR significantly reducing DLIND, consistent with the contractionary effects predicted by the IS-LM model. Similarly, negative coefficients for DLGE, DLM3, and DLTAX suggest fiscal crowding-out effects or inefficient spending. Currency depreciation (DLEX), however, supports industrial growth—consistent with export-led growth theory—by enhancing competitiveness. Inflation within the target range (DM1) slightly reduces output, while inflation above the target (DM2) has a more pronounced negative impact, highlighting the inflation sensitivity of industrial production. This regime is relatively stable (σ

1 = 0.0035), though short-lived, with an average duration of two months.

In contrast, the Bearish Regime (State 2) is marked by policy ineffectiveness and elevated volatility (σ2 = 0.0422). The interest rate still negatively affects industrial growth, but the weaker coefficient (−0.6223) suggests reduced monetary transmission, consistent with theories of policy ineffectiveness during downturns. Fiscal and monetary indicators (DLGE, DLM3, DLTAX) are insignificant, indicating muted policy influence. Nevertheless, the exchange rate (DLEX) maintains a strong positive effect on industrial activity, underscoring the external sector’s role as a stabiliser during economic distress. Inflation variables (DM1, DM2) lose statistical significance in this regime, possibly due to firms focusing more on survival than inflationary conditions in times of uncertainty.

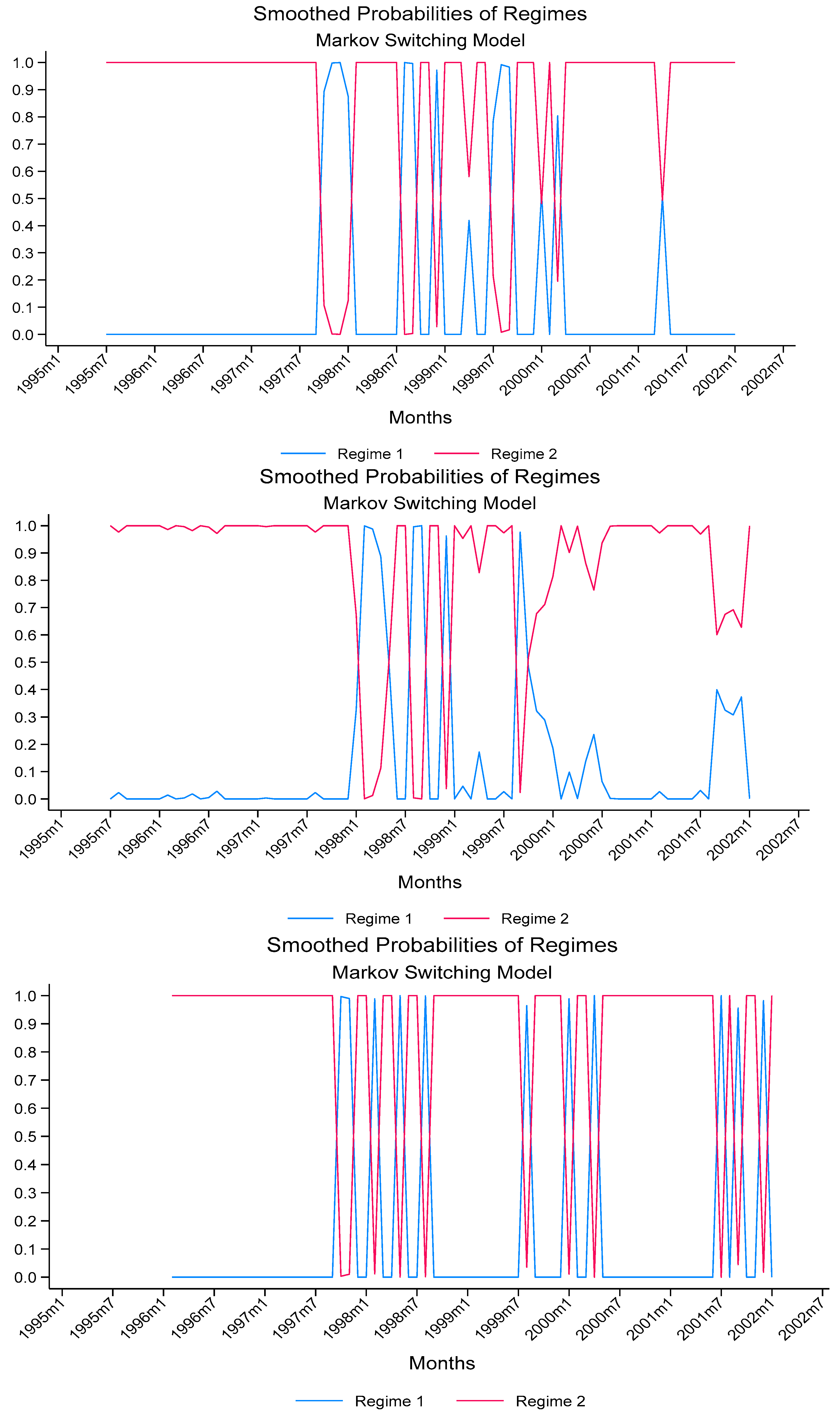

The transition dynamics highlight distinct structural asymmetries between the two regimes. The Bullish Regime appears short-lived and unstable, transitioning approximately 53.56% of the time into the Bearish Regime. In contrast, the Bearish Regime exhibits strong persistence, with an average duration of about 11 months, signifying its dominance during the pre-inflation targeting period. Correspondingly,

Figure 1 presents the smoothed regime probabilities, which clearly depict the timing and prevalence of each regime over the sample period. The graphical evidence corroborates the transition estimates, confirming that Regime 2 (Bearish phase) prevailed for the greater part of the pre-inflation targeting era, consistent with the high expected duration reported in

Table 4. These findings align with regime-switching theory and South African historical experience, where weak policy credibility and macroeconomic volatility prior to inflation targeting limited the effectiveness of both fiscal and monetary tools. The consistent positive effect of exchange rate depreciation across both regimes suggests that, in the absence of strong domestic policy traction, external competitiveness played a critical role in sustaining industrial growth.

The Effect of Monetary and Fiscal Policy Variables on the Financial Index Pre-Inflation Targeting Period

In the Bullish Regime (State 1), DLFIN is significantly shaped by macroeconomic fundamentals. As shown on

Table 3, DLIR: −1.5002 exhibits a strong and significant contractionary effect, consistent with monetary theory that links higher borrowing costs to reduced financial intermediation. DLGE: 0.3935 positively influences DLFIN, suggesting that fiscal expansion supports financial development, in line with Keynesian views. However, DLEX is statistically insignificant in this regime, indicating that currency fluctuations play a limited role during periods of economic optimism. Inflation above the target range (DM2: −0.2583) significantly undermines financial sector performance, reinforcing the notion that inflationary shocks erode investor confidence and financial stability.

In the Bearish Regime (State 2), the macroeconomic impact on DLFIN becomes more externally driven and less policy-responsive. The effect of DLIR weakens (–0.2329), implying diminished monetary policy transmission under contractionary conditions. Fiscal variables such as DLGE, DLTAX, and DLM3 do not significantly affect DLFIN, pointing to reduced effectiveness of both fiscal and monetary tools in stimulating financial activity during downturns. In contrast, DLEX (0.5359) becomes highly significant, suggesting that the financial sector becomes more sensitive to exchange rate volatility, possibly due to increased exposure to currency risks and capital outflows.

The Bullish Regime has a 48.89% probability of remaining in State 1 and a 51.11% chance of shifting to State 2, with an average duration of about two months (

Table 4). In contrast, the Bearish Regime is more persistent, remaining in State 2 91.66% of the time and lasting roughly twelve months.

Figure 1 illustrates the smoothed regime probabilities, confirming the dominance of the Bearish phase throughout most of the pre-inflation targeting period, consistent with the high expected duration reported in

Table 4. These patterns are consistent with empirical evidence from emerging markets, where financial sectors are particularly vulnerable to inflationary shocks and external imbalances. The findings highlight the importance of credible inflation control and macroeconomic coordination to sustain financial sector growth and resilience across regimes.

The Effect of Monetary and Fiscal Policy Variables on Resources Index Pre-Inflation Targeting Period

In the Bullish Regime (State 1), the results reveal a strong contractionary effect of monetary policy on DLRE, as indicated by the significant negative coefficient on DLIR. This is consistent with classical monetary theory, where rising interest rates increase the cost of capital, discouraging investment in resource-intensive sectors. DLEX and the inflation regime dummies (DM1 and DM2) also exert negative pressure on DLRE, implying that currency depreciation and inflationary conditions reduce resource sector growth, possibly through higher input costs and reduced profitability. Conversely, DLM3 and DLGE positively affect DLRE, suggesting that expansionary monetary and fiscal policies can stimulate resource sector activity under favourable conditions.

In the Bearish Regime (State 2), DLIR and DLTAX have significant negative impacts on DLRE, aligning with the view that tighter monetary conditions and higher tax burdens reduce returns and dampen activity in resource-based industries. However, DLGE and DLM3 lose significance, implying reduced policy effectiveness during periods of heightened economic uncertainty. The positive coefficient on DM1 suggests that State 2 is distinct from the previous regime, reflecting possible structural or policy changes. The higher regime variance (sigma2) confirms the increased volatility in this state, indicative of instability in macroeconomic fundamentals or external shocks that disproportionately affect resource-driven sectors.

Regime transition dynamics show that State 1 is relatively short-lived, with only an 8.95% probability of remaining in the same state and an expected duration of about 1.1 months, suggesting transitory stability. In contrast, State 2 displays greater persistence, with an 83.79% probability of remaining and an average duration of 6.2 months. These findings echo empirical studies in emerging economies, where resource sectors often face procyclical volatility and are more vulnerable to sustained periods of policy uncertainty and external disturbances.

Heterogeneity Across Sectors Pre-Inflation Targeting Period

The analysis reveals sectoral heterogeneity in response to macroeconomic variables across two states, as shown in

Table 3. In State 1, the growth rate of the interest rate (DLIR) significantly negatively impacts all sectors, with the strongest effect on the financial sector. Government expenditure (DLGE) has a significant positive effect on the financial and resources sectors, while the growth rate of money supply (DLM3) negatively affects the industrial and financial sectors but positively influences resources. Taxes (DLTAX) show a negative effect on the industrial and resources sectors, with a small positive effect on the All-Share Index (DLALL). Exchange rates (DLEX) positively affect the industrial sector and the All-Share Index, while having a significant negative impact on the resources sector. The regime dummies (DM1, DM2) indicate a negative shift for all sectors, with stronger effects on the industrial and resources sectors.

In State 2, the impacts of these macroeconomic variables become weaker and more varied. The growth rate of interest rates (DLIR) remains negative for all sectors but with reduced significance, particularly for the financial sector. Government expenditure (DLGE) shows minimal effects, while the growth rate of money supply (DLM3) becomes largely insignificant across sectors. Taxes (DLTAX) have a significant negative impact only on the resources sector. Exchange rates (DLEX) show a positive effect on the financial sector, but this is insignificant for others. The regime shift is indicated by a positive relationship with DM1 in the financial sector, and weaker effects in the industrial and resources sectors. Overall, State 2 shows greater volatility and less consistent sectoral responses compared to State 1.

5.3. Markov Switching Dynamic Regression During Inflation Targeting Regime

5.3.1. The Effect on Monetary and Fiscal Policy Variables on Industrial Index During Inflation Targeting Period

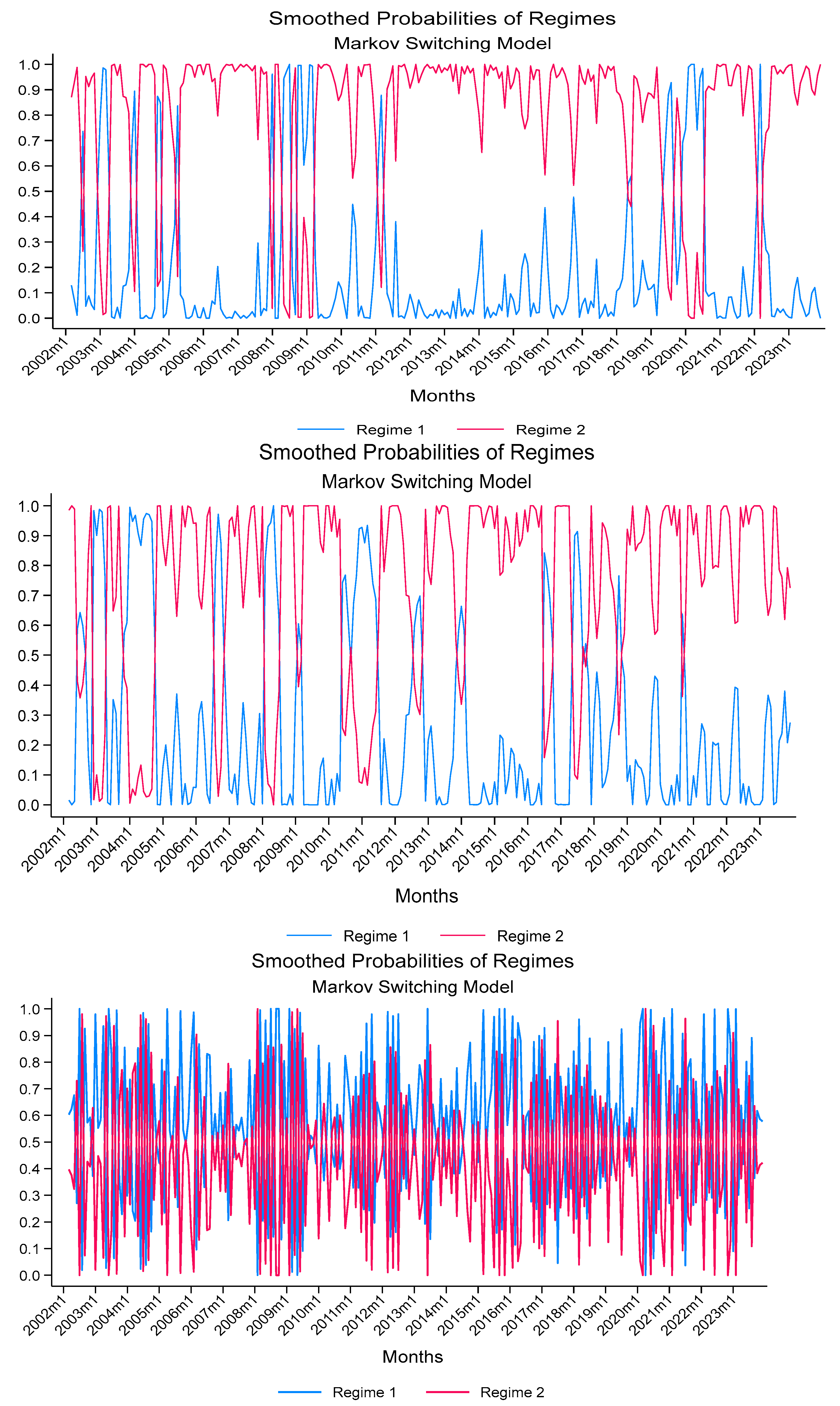

The results from the Markov Switching model reveal two distinct economic regimes. In State 1 (Bearish Regime), industrial returns are negatively influenced by factors like government expenditure and money supply growth, both exhibiting statistically significant negative coefficients. Inflation within the target range (3–6%) and inflation above 6% also correlate with lower industrial returns, while exchange rate depreciation has a positive effect. The economy remains in this bearish state for a relatively short period, with an expected duration of approximately 2.4 months and a high probability of transitioning to a more favourable regime (41.7%).

In State 2 (Bullish Regime), the industrial sector benefits from money supply growth and exchange rate depreciation, both of which positively affect industrial returns. While interest rate growth has a negative impact, it is less pronounced compared to State 1. The inflation-related dummy variables do not significantly influence industrial returns in this state, which is associated with prolonged economic expansion. The economy has a high probability of remaining in State 2 (90.1%), with an expected duration of approximately 10.1 months, indicating a prolonged period of favourable conditions for industrial growth.

Figure 2, which presents the smoothed regime probabilities, visually confirms this persistence, showing that State 2 dominated for most of the sample period, consistent with the transition dynamics reported in

Table 4.

5.3.2. The Effect on Monetary and Fiscal Policy Variables on Financial Index During Inflation Targeting Period

In State 1 (Bearish Regime), the financial returns are significantly influenced by money supply growth, which has a positive effect, and by government expenditure and tax revenue growth, which both have negative coefficients. Inflation above the target range (DM2) also has a significantly negative effect on financial returns, indicating that higher inflation is detrimental to the financial sector. Exchange rate growth (DLEX) and inflation within the target range (DM1) do not appear to have a statistically significant effect in this state. The economy remains in this bearish state for a relatively short period, with an expected duration of approximately 2.4 months.

In State 2 (Bullish Regime), exchange rate growth (DLEX) has a strong positive impact on financial returns, suggesting that a depreciating exchange rate benefits the financial sector in this regime. Interest rate growth (DLIR) has a positive but weak impact, while other factors like money supply growth, government expenditure, and tax revenue growth are not significant in this state. Inflation-related dummy variables (DM1 and DM2) do not show any significant effects on financial returns in this state. The economy is likely to stay in this favourable state for a much longer period, with an expected duration of approximately 10.1 months, reflecting a more stable and prolonged period of financial sector growth.

5.3.3. The Effect of Monetary and Fiscal Policy Variables on Resources Index During Inflation Targeting Period

The Resources Index exhibits two distinct market conditions: State 1 (moderate/bullish) and State 2 (bearish/volatile), with average durations of 1.6 months and 1.2 months, respectively, indicating frequent shifts between regimes. In State 1, interest rate growth (DLIR) has a positive and significant effect, suggesting that rising interest rates do not immediately harm resource stocks, potentially due to strong global commodity demand. Similarly, exchange rate growth (DLEX) positively impacts returns, implying that a weaker local currency benefits resource exporters. However, high inflation (DM2) significantly reduces returns, indicating that inflation beyond 6% creates cost pressures that outweigh any benefits from rising commodity prices.

In State 2, the market appears bearish, with a strong negative impact of interest rate growth, suggesting that in this state, higher borrowing costs dampen investment and profitability in resource industries. Exchange rate growth (DLEX) also has a significantly negative effect, implying that in this regime, currency depreciation does not provide the expected export advantage, possibly due to external shocks or declining global demand. Interestingly, government expenditure (DLGE) positively affects returns in this state, hinting that fiscal support may stabilise the sector during downturns. Inflation dummies (DM1 and DM2) are positively associated with returns, suggesting that during bearish conditions, inflation may coincide with commodity price increases that provide some relief to resource stocks. Given the frequent transitions between the two states, the resource sector appears highly sensitive to macroeconomic fluctuations, particularly interest rate movements and exchange rate shifts.

5.3.4. Heterogeneity Across Sectors During Inflation Targeting Period

The results highlight sectoral heterogeneity in response to macroeconomic variables across the industrial (DLIND), financial (LFIN), resources (DLRE), and overall market (DLALL) indices. In State 1, the prime lending rate (DLIR) has a significantly positive effect on industrial, resources, and overall market indices, while its impact on the financial sector is negligible. Government expenditure (DLGE) negatively affects the industrial and financial sectors, while money supply (DLM3) has opposite effects, negatively influencing industrial output but positively affecting the financial sector. Exchange rate fluctuations (DLEX) significantly impact all sectors except financials, with positive effects on industrial, resources, and overall market indices.

In State 2, the industrial and overall market indices show negative sensitivity to the interest rate, whereas the financial sector benefits. Government expenditure positively influences the resources sector but remains insignificant for others. The financial sector is highly responsive to exchange rate changes, while the resources sector experiences a strong negative impact. Money supply positively affects the industrial and overall market indices, while tax revenue (DLTAX) has minimal influence across all sectors. Additionally, regime dummies (DM1, DM2) indicate varying shifts in market dynamics, particularly for resources and overall market indices.

The differences in sectoral responses underscore the varying sensitivities of industries to monetary and fiscal policy shifts. The industrial and resources sectors exhibit stronger reactions to interest rate and exchange rate movements, while the financial sector is more influenced by money supply and exchange rate changes. The overall market index reflects a composite effect, with significant influences from multiple macroeconomic factors. The persistence of structural differences across states suggests the importance of sector-specific policy considerations in managing economic fluctuations.

5.4. Asymmetries Between Pre-Inflation Targeting and During Inflation Targeting

The results reveal notable asymmetries in the macroeconomic and financial determinants of sectoral indices before and during the inflation-targeting regime. Prior to inflation targeting, interest rate (DLIR) had a significantly negative impact across all indices in State 1, with coefficients ranging from −1.0867 to −2.7514, while in State 2, its effect was generally weaker. Government expenditure (DLGE) showed mixed effects, being negative for DLIND (−0.0892) but positive for DLFIN (0.3935). Money supply (DLM3) exhibited a strong negative impact in State 1, especially on DLALL (−2.3595), whereas in State 2, its influence became statistically insignificant. The exchange rate (DLEX) showed both positive and negative effects, with a strikingly strong negative impact on DLRE (−2.2443) in State 1, but a positive effect on DLIND (0.3518) and DLALL (1.3959). The standard deviations (sigma) were relatively higher, suggesting greater volatility before the inflation-targeting regime.

During the inflation-targeting period, significant shifts occurred in both the magnitude and direction of the estimated coefficients. Interest rate (DLIR) became positive for DLIND (0.4232) and DLALL (1.5219) in State 1, reflecting a reversal in its impact, while remaining negative for DLRE (−1.0058) in State 2. Government expenditure (DLGE) remained largely insignificant, whereas money supply (DLM3) turned positive for DLFIN (1.7284) but remained negative for DLIND (−1.4795). The exchange rate (DLEX) had a strong positive effect on DLIND (0.7751) and DLALL (0.8290), while its effect on DLRE remained negative (−0.8503) in State 2. The statistical significance of tax revenue (DLTAX) diminished, except for DLFIN (−0.0142 in State 1), indicating reduced fiscal policy influence. Moreover, regime dummy variables (DM1 and DM2) retained their significance, underscoring persistent regime shifts. Interestingly, volatility, as reflected by sigma values, showed a reduction in some cases (for example, DLIND from 0.0422 to 0.0291), suggesting increased stability during inflation targeting.

Overall, the results suggest that inflation targeting altered the macro-financial dynamics, particularly by mitigating the adverse effects of interest rates on certain sectors while stabilising volatility. The reversal in the impact of interest rates on DLIND and DLALL suggests that monetary policy became more effective in promoting these sectors during inflation targeting. Additionally, the shift in the significance of money supply and exchange rate effects implies structural changes in financial transmission mechanisms. The findings highlight the differential sectoral responses to policy shifts, with DLFIN and DLALL benefiting more from inflation targeting, while DLRE continued to experience persistent exchange rate vulnerabilities.

5.5. Sensitivity and Robustness Analysis

Sensitivity and robustness checks were conducted to validate the Markov-switching results for the three sectoral indices. For the pre-inflation-targeting period, information criteria suggested alternative regime specifications, but the SBIC consistently favoured the more parsimonious two-regime model. Sensitivity tests confirmed this choice: for DLIND, the qualitative regime structure and coefficient signs remained stable across specifications with different switching rules, while variance-switching models significantly improved fit and yielded stronger policy effects in downturns. For DLFIN, the two-regime fixed-variance specification produced stable and interpretable results, whereas the variance-switching model failed to converge and a three-regime model, though statistically viable, lacked theoretical alignment with the bullish–bearish dichotomy central to the analysis. In contrast, DLRE exhibited clear regime-dependent volatility, with the unrestricted two-regime variance-switching model providing the best fit, capturing sharp contrasts in tranquil versus turbulent states. Across indices, three-regime models generally failed to converge, underscoring the empirical and theoretical robustness of the two-regime specification.

During the inflation-targeting period, the robustness of the two-regime MS-DR models was further assessed. For DLIND, alternative specifications—including models without variance switching and those with restricted switching variables—produced results consistent with the baseline, confirming that exchange rate movements remain the dominant driver of industrial performance, fiscal expenditure exerts a stronger contractionary effect in bearish regimes, and monetary policy impacts are state-dependent. Three-regime extensions failed to converge, reinforcing the appropriateness of the binary regime structure. For DLFIN, the adopted two-regime model with regime-dependent coefficients aligned most closely with theoretical expectations of bullish and bearish cycles. Although alternative specifications yielded comparable results and a three-regime model offered a slightly better fit, the latter captured stable–volatile–crisis phases rather than the binary cycles relevant to this study.

Robustness checks for DLRE during the inflation-targeting period confirmed the superiority of the two-regime variance-switching specification. Compared with fixed-variance and restricted-switching alternatives, the variance-switching model consistently achieved the best fit while preserving the qualitative structure of regime dynamics. The results collectively demonstrate that across both periods, the core findings are robust to alternative specifications: external shocks and exchange rate movements emerge as the most influential drivers of sectoral performance, fiscal variables exert stronger effects in contractionary states, and monetary policy impacts vary across regimes. The evidence therefore substantiates the theoretical characterisation of regime-dependent dynamics in South Africa’s industrial, financial, and resources sectors.

6. Discussion

This study set out to investigate how South Africa’s monetary and fiscal policies influence the performance of key stock market sectors—industrial, financial, and resource-based—and how these relationships have evolved across distinct policy regimes. The analysis focused on assessing whether the transition to the inflation-targeting (IT) framework in 2002 altered sectoral dynamics and whether policy effects vary under differing market conditions. The findings reveal that monetary and fiscal policies exert heterogeneous and state-dependent effects on sectoral stock returns, reflecting variations in structural composition and exposure to macroeconomic conditions. Notably, the financial and industrial sectors demonstrated greater responsiveness to the stabilising influence of the IT regime, while the resource sector remained more vulnerable to external shocks and cyclical fluctuations. Overall, the results underscore that the effectiveness of macroeconomic policies in shaping sectoral performance is contingent on both the prevailing economic regime and the broader market environment.

6.1. Interest Rate Dynamics and Policy Implications

In the pre-inflation targeting regime, the analysis reveals that higher interest rates exert a contractionary effect across all sectors, with the financial sector (DLFIN) being the most adversely impacted. This finding underscores the role of elevated borrowing costs in curtailing financial activity during periods of economic optimism. However, in economic downturns, the impact diminishes, particularly for the financial sector, which becomes less sensitive to interest rate fluctuations during recessions. This aligns with the broader macroeconomic theory that suggests the financial sector’s sensitivity to interest rates is cyclical, more pronounced during expansions and subdued during contractions (

Gubareva & Borges, 2022).

In the inflation-targeting regime, the sectoral responses to interest rates exhibit a marked shift. During bullish phases, higher interest rates positively influence the Resources Index (DLRE), which points to the stabilising role of inflation targeting in capital markets. This effect is consistent with the objectives of inflation targeting, where a controlled interest rate environment can promote stability and foster investment in capital-intensive sectors. However, during recessions, elevated interest rates exacerbate economic contractions, particularly in sectors like resources, which are highly sensitive to borrowing costs. Interestingly, the industrial sector (DLIND) shows a positive response, suggesting that firms may still pursue growth despite higher borrowing costs, likely driven by structural adjustments within the sector.

The observed interest rate dynamics provide key insights into the sectoral transmission of monetary policy across different regimes. The findings show that monetary tightening has contractionary effects on financial and resource-based sectors, particularly before inflation targeting, underscoring their sensitivity to borrowing costs. Under the inflation-targeting framework, the industrial sector’s relative stability amid higher rates suggests improved adaptability and structural resilience. These outcomes imply that monetary policy under inflation targeting has enhanced macro-financial stability, though its sectoral effects differ markedly. Effective policy design should therefore recognise these asymmetries, ensuring that interest rate adjustments are complemented by supportive fiscal measures to sustain sectoral growth and minimise vulnerability during downturns.

6.1.1. Government Expenditure and Policy Implications

Before the adoption of inflation targeting, DLGE had a positive impact on both DLFIN and the DLRE during bullish states, indicating that fiscal expansion helped drive growth in these sectors. However, it negatively affected the DLIND, likely due to inefficiencies or potential crowding-out effects. During downturns, the effectiveness of fiscal policy diminished, as the impact of DLGE became insignificant across most sectors. This suggests that fiscal policy was less responsive and less effective in stabilising the economy during recessions before inflation targeting was introduced.

Under inflation targeting, the effects of DLGE exhibit a shift. During economic expansions, the positive impact of government spending on the financial and resources sectors weakens, while the negative effects on DLIND and DLFIN become more pronounced. Interestingly, during recessions, government expenditure becomes more impactful, particularly stimulating the DLRE, while continuing to negatively affect DLIND and DLFIN. These results highlight the adaptive role of government expenditure in different phases of the economic cycle, with its effectiveness being more pronounced in times of economic contraction under inflation targeting.

The findings suggest that fiscal policy plays a crucial role in shaping sectoral performance, but its effects vary across industries and phases of the economic cycle. Enhancing the growth impact of government expenditure may therefore depend on improving the efficiency and composition of public spending, particularly in ways that support productive investment and sectoral competitiveness. While the results do not directly evaluate employment outcomes, the evidence of asymmetric fiscal effects highlights the potential for targeted expenditure frameworks to stabilise output and strengthen the resilience of labour-intensive sectors during economic downturns.

6.1.2. Money Supply and Policy Implications

In the pre-inflation targeting regime, DLM3 has a negative effect on DLIND during bullish states, suggesting that excessive liquidity may lead to inflationary pressures, which suppress industrial growth. It has an insignificant impact on DLFIN but positively influences DLRE, potentially due to the capital-intensive nature of the resources sector. During economic downturns, the effects of the money supply become weaker and largely insignificant across all sectors, reflecting diminished effectiveness of monetary policy in times of recession.

Under inflation targeting, the money supply (DLM3) shows a shift in its effects. During economic expansions, it positively impacts DLIND, possibly due to a more targeted approach in channelling liquidity to industrial activities. However, its effects remain insignificant for other sectors. In recessions, the money supply becomes more influential in stimulating DLFIN but exerts a negative impact on DLIND, which may reflect distortions caused by liquidity excess or higher inflation expectations. These findings underscore the changing role of the money supply under different economic conditions and policy frameworks.

The findings indicate that the transmission of monetary policy through the money supply channel exerts varying effects across sectors, reflecting structural differences in financial intermediation and capital market depth. Strengthening the effectiveness of monetary policy may therefore depend on improving the linkages between liquidity expansion and productive investment, particularly in sectors with limited access to financial markets. While the present analysis does not explicitly examine credit allocation or employment effects, the results suggest that the impact of money supply growth is more pronounced in financially integrated sectors. This underscores the importance of reinforcing monetary transmission mechanisms to ensure that liquidity growth translates into broader sectoral performance and economic stability.

6.1.3. Tax Revenue and Policy Implications

Prior to inflation targeting, DLTAX exerts a negative impact on both DLIND and DLRE during economic expansions, suggesting that higher taxation limits growth in these sectors. During downturns, the effects of taxation become mixed, with a significant negative impact on DLRE but largely insignificant effects on the industrial and financial sectors. This highlights the contractionary nature of taxation in both phases, with stronger negative effects during recessions.

Under inflation targeting, DLTAX exhibits minimal effects during economic expansions but exerts a more pronounced negative impact on DLFIN during downturns. DLRE shows weak or insignificant responses, indicating that taxation became less effective and more unpredictable under inflation targeting, especially during periods of economic stress. This shift suggests that the effectiveness of tax policy was greater in the pre-inflation targeting regime.

The results highlight that the effects of tax policy differ significantly across sectors and economic regimes. Before inflation targeting, higher tax burdens appear to have constrained activity in key sectors such as manufacturing and resources, whereas under the inflation-targeting framework, the sectoral effects of taxation became more moderate, suggesting improved fiscal discipline and coordination. These outcomes imply that the design and implementation of tax policy play a crucial role in shaping sectoral performance and investment behaviour. While the present analysis does not explicitly assess employment outcomes or distributional impacts, the observed asymmetries in sectoral responses underscore the importance of aligning revenue objectives with industrial performance to sustain growth in sectors that drive productivity and competitiveness.

6.1.4. Exchange Rates and Policy Implications

Before inflation targeting, exchange rate fluctuations (DLEX) exert a strong positive effect on the DLIND but negatively impact DLRE, while their influence on DLFIN remains insignificant. During downturns, the effects of exchange rate fluctuations remain positive and significant for both the industrial and financial sectors but turn insignificant for the resources sector. This suggests that exchange rate movements play a critical role in the performance of the industrial and financial sectors during periods of economic expansion and contraction.

Under inflation targeting, exchange rate movements positively affect all sectors during bullish states, with DLFIN exhibiting the strongest response. However, during downturns, exchange rate fluctuations continue to support the DLIND but have a negative impact on DLRE. These findings highlight the varying effects of exchange rate dynamics, with the impact on sectoral performance being contingent on the prevailing economic conditions and the policy regime in place.

To mitigate the adverse effects of exchange rate volatility and enhance industrial competitiveness, policymakers should prioritise exchange rate stability, especially for export-driven industries. Moreover, the development of targeted industrial export support programmes, such as hedging mechanisms and financial assistance for manufacturers, would help shield firms from exchange rate fluctuations, fostering resilience and promoting sustainable growth across key economic sectors.

6.1.5. Inflation Targeting and Sectoral Performance

The inflation-targeting dummy (DM1) indicates that stable inflation negatively impacts the industrial and resource sectors in bullish states, likely due to the contractionary policy stance that restricts credit access and investment incentives. Conversely, the high-inflation dummy (DM2) reveals that inflation exceeding 6% significantly reduces industrial and resource sector performance, suggesting that inflation volatility discourages long-term investment and economic stability.

To address these challenges, policymakers should adopt a flexible inflation-targeting framework that considers industrial growth alongside price stability. Expanding industrial financing mechanisms during periods of inflation stability would ensure continued investment in manufacturing and resource sectors, fostering economic resilience and sustainable development.

The results underscore a critical policy challenge: monetary and fiscal policies have disproportionately benefited the financial sector, while the industrial and resource sectors have remained vulnerable. Although inflation targeting has contributed to macroeconomic stability, it has not sufficiently stimulated industrial production or supported resource-based employment. A recalibrated policy approach, integrating industrial development objectives into monetary and fiscal strategies, is necessary to drive inclusive economic growth.

6.2. Policy Implications

Interest rate policies should be fine-tuned to avoid over-tightening during recessions, particularly for capital-intensive sectors. Fiscal policies need sector-specific focus, prioritising employment-generating industries such as manufacturing. The effectiveness of monetary policy can be improved through targeted liquidity provision and sectoral credit support. Exchange rate management remains crucial for resource-dependent sectors exposed to global commodity cycles.

6.3. Contribution to Literature

This research adds to the discourse by demonstrating how the interplay between policy regimes and economic cycles shapes sectoral outcomes. It also provides empirical backing for the heterogeneous effects of policy tools, reinforcing calls for adaptive, sector-sensitive macroeconomic frameworks.