1. Introduction

The design of effective retirement savings systems remains a central challenge for policy makers and researchers, particularly in economies facing unemployment, income volatility, and demographic pressures (

Gallego-Losada et al., 2022;

Koka & Kosempel, 2014;

Wang et al., 2016). Traditional pension schemes emphasize the accumulation of locked retirement wealth, accessible only upon reaching retirement age, under the implicit assumption of stable, uninterrupted careers and predictable lifespans (

Andersen et al., 2024;

Clements et al., 2014;

GTAC, 2011;

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Long-Run Macroeconomic Effects of the Aging U.S. Population, 2012). However, these assumptions are often invalid in emerging economies, where labor market instability and frequent income shocks undermine long-term savings. Extensive empirical evidence demonstrates that in many developing and emerging economies such as South Africa, high unemployment rates, irregular labor force participation, and volatile earnings fundamentally undermine these assumptions (

Gomes et al., 2008;

Mitchell & Turner, 2009). In such contexts, individuals experience frequent income shocks and contribution gaps, limiting their ability to sustain long-term savings without periodic access to liquidity. This tension between liquidity needs and retirement preservation motivates the investigation of pension reforms that incorporate flexible savings components (

Beshears et al., 2015).

Globally, some retirement systems have sought to address this tension by incorporating flexible or moderately liquid components within pension savings, often referred to as “liquid pots” or flexible withdrawal thresholds. Providing international context highlights how other systems balance liquidity and preservation, which can inform local policy design. For example, Australia’s superannuation system allows partial withdrawals from restricted non-preserved amounts under certain conditions, despite general preservation rules (

The Treasury, Australian Government, 2020). The United Kingdom’s pension freedoms allow individuals aged 55 and older to withdraw from defined contribution pensions with considerable flexibility (

Department for Work and Pensions, 2017). In the United States, Roth IRAs provide a liquid portion of retirement savings accessible without penalty at any time, although most traditional accounts maintain early withdrawal restrictions (

Internal Revenue Service, 2024). Similarly, Chile has introduced emergency withdrawal provisions in its typically restrictive pension system (

Inzunza & Madeira, 2025), while New Zealand’s KiwiSaver allows moderate early access for specific needs such as first-home purchases (

Inland Revenue Department, New Zealand, 2025). Nevertheless, fully unrestricted access before retirement age remains rare, as systems strive to balance liquidity with long-term retirement income security. Highlighting these global examples underscores the novelty and relevance of South Africa’s two-pot system in the international context.

The economic literature has explored various aspects of retirement savings behavior, including optimal portfolio allocation between risky and risk-free assets (

Assabil & Abubakar, 2025;

Moreira et al., 2025), the impact of liquidity constraints on intertemporal consumption smoothing (

Angerer et al., 2025;

Duffy & Orland, 2025), and the role of social safety nets in securing retirement incomes (

Jung & Tran, 2012;

Pattar & Kumar Mehta, 2024). More recent studies have examined multi-pot pension systems that explicitly separate liquid savings from long-term locked funds to reduce consumption volatility and promote retirement wealth accumulation (

Amromin & Smith, 2003;

Riekert, 2025;

Wang-Ly & Newell, 2022). However, most of these models assume stable employment trajectories and do not capture high unemployment or shortened careers, limiting their applicability to emerging economies like South Africa.

In South Africa, these issues have recently taken center stage with the introduction of the two-pot retirement system by the national treasury, scheduled to take effect on 1 September 2024 (

Investec Limited, 2024;

South African Reserve Bank, 2024). The reform represents a localized policy innovation designed to address persistent liquidity needs while enforcing partial preservation. The reform seeks to strike a balance between preserving the majority of retirement savings and allowing limited, periodic withdrawals to meet emergency liquidity needs. Under the new rules, one-third of new contributions will be directed into a “savings pot” accessible during working life, while two-thirds will be locked in a “retirement pot” until retirement. Pre-existing savings will be ringfenced into a “vested pot,” with a one-off “seeding” transfer providing immediate liquidity. The policy responds to persistent evidence of large-scale pre-retirement withdrawals: Government data show that in each of the three years preceding reform, more than 700,000 individuals accessed a withdrawal lump sum before retirement, totalling roughly ZAR 78 billion annually, equivalent to nearly one-third of all yearly retirement contributions (

National Treasury of South Africa, 2021). The average withdrawal was around ZAR 110,000, and tax revenues from such withdrawals exceeded ZAR 12 billion per year. These leakages contribute to low replacement rates, with the average South African retiree replacing only 25–30% of their final salary (

Sanlam Corporate, 2021).

Household vulnerability exacerbates the problem: Over one-third of South Africans have savings to last one month or less, and more than half report high financial stress (

Old Mutual South Africa, 2021). This highlights the importance of designing a pension system that provides both liquidity for immediate needs and long-term retirement security. In this environment, restricted preservation rules often incentivize lump-sum cash-outs upon job loss or resignation, particularly given the formal unemployment rate of 33%. The two-pot system’s design aims to mitigate this by providing a controlled liquidity channel without allowing full cash-out, but its real-world effects will depend critically on how households adjust their withdrawal behavior in response to liquidity access. Indeed, early indications from SARS data suggest strong demand: By May 2025, approximately 2.69 million South Africans had withdrawn from their savings pots under the new system’s rules (

Polity.org.za, 2025).

In this study, we develop a stochastic two-pot retirement savings model that explicitly integrates labor market uncertainty. Our model improves on previous approaches by using a Monte Carlo simulation of Markov chain-modeled career paths to capture probabilistic employment, unemployment spells, and contribution gaps. Our approach departs from much of the literature by modeling career paths using a Monte Carlo simulation based on a Markov chain, which captures the probabilistic nature of job loss, unemployment spells, and contribution gaps. This framework allows us to directly evaluate the welfare implications of different pension designs for individuals facing realistic labor market risks. Our contribution is twofold. First, we formalize the interaction between stochastic labor market uncertainty and retirement saving decisions within a dynamic optimization framework. By calibrating the model to the South African socio-economic context, we provide quantitative insights into how a worker’s lifetime welfare, as measured by CRRA utility, is impacted by various liquidity-allocation strategies. Second, we use this framework to critically assess the new two-pot system. In doing so, we challenge the prevailing assumption that fixed contribution splits such as the one-third/two-thirds division are universally optimal, and we highlight the importance of tailoring pension design to the realities of unstable labor markets.

This study is structured as follows. The introduction is

Section 1, followed by a methodology that consists of a stochastic employment model, discrete time model, and life time utility maximization model in

Section 2. The model is validated in

Section 3 strictly in South African context, and the discussion and conclusion follow in

Section 4 and

Section 5, respectively.

2. Methodology

We develop a parsimonious yet analytically tractable two-pot retirement savings model that integrates labor market uncertainty to evaluate the South African two-pot system. The model captures the key trade-off workers face in allocating contributions between a liquid savings pot and a locked retirement pot. Individuals’ preferences are modeled using a CRRA utility function with risk aversion parameter , and consumption is discounted by a factor , ensuring that intertemporal choices are accounted for. The primary objective is to identify the allocation fraction p that maximizes expected lifetime utility across stochastic career paths.

The model makes several simplifying assumptions to maintain analytical tractability while capturing key features of the South African context. We represent the labor market as a two-state Markov chain (employed/unemployed) to explicitly model employment uncertainty, reflecting the high and volatile unemployment environment. Contributions are split by a fixed fraction p between a liquid savings pot and a locked retirement pot, directly aligning with the South African two-pot policy and allowing clear welfare comparisons without complicating optimization. Retirement wealth is annuitized over a fixed horizon, and salaries grow at a constant real rate, isolating the impact of labor market volatility on saving outcomes. Individual preferences follow the CRRA utility function, a standard choice enabling robust evaluation of lifetime welfare under risk.

A core innovation of this model is the integration of a Monte Carlo simulation framework. By generating thousands of stochastic career trajectories that incorporate probabilistic employment and unemployment spells, we can evaluate how different allocations between liquid and locked pots affect lifetime consumption and retirement outcomes under realistic labor market dynamics. Contributions occur only during periods of employment, while withdrawals from the liquid pot smooth consumption during unemployment, subject to policy-specific caps and floors. The retirement pot remains locked until retirement, at which point the accumulated wealth is annuitized over a fixed retirement horizon . Our modeling framework proceeds in three stages: (i) We simulate stochastic employment histories using a calibrated Markov chain, (ii) we use these histories to drive a discrete-time dynamic model of savings and consumption, and (iii) we compute the resulting consumption streams in a lifetime utility maximization framework.

2.1. Stochastic Employment Model

We model the individual’s employment status as a two-state Markov chain, where the states are ’employed’ (E) and ’unemployed’ (U). We calibrate the transition probabilities using South African labor market data on average job tenure and the long-run unemployment rate. Let the transition matrix be defined as

where

denotes the probability of transitioning from state

i to state

j. Steady-state probabilities satisfy the balance equations and normalization condition:

Substituting

and

, we have

Rearranging terms yields

which simplifies to

to obtain the steady-state

The average job duration,

, and average unemployment duration,

, are given by

and

in the South African context (

Pnet, 2024;

Writer, 2022).

This ensures that the long-run steady-state distribution of employment matches observed labor market data, providing a validated foundation for the stochastic simulations.

2.2. Discrete-Time Dynamic Model

We consider a worker who contributes to a retirement system over a nominal career of length

years. The individual allocates a fixed fraction

of their annual contribution

to an accessible savings pot, with the remainder

going to a locked retirement pot. The contribution

is a fixed fraction of salary growing at rate

g. Pot balances evolve according to

where

and

are the pot balances at the beginning of year

t,

r is the real investment return, and

is the withdrawal from the savings pot. During employment, contributions are made (

) and consumption is a fixed fraction of salary; during unemployment,

and withdrawals from the liquid pot finance consumption, subject to minimum and maximum policy constraints.

2.3. Lifetime Utility Maximization

The model employs a CRRA utility function

where

denotes consumption at time

t and

is the risk aversion coefficient. Time preference is incorporated through a discount factor

. Expected lifetime utility sums discounted utility over both working and retirement phases, allowing explicit evaluation of consumption smoothing under stochastic employment and investment returns. Monte Carlo simulations generate multiple lifetime trajectories, and averaging over these scenarios provides the expected utility for a given allocation

p. By systematically varying

p, we identify the welfare-maximizing allocation that balances liquidity needs during unemployment against long-term wealth accumulation. This explicitly demonstrates how the methodology captures the interplay of labor market uncertainty and investment risk in determining optimal pension design.

3. Model Validation

This section evaluates the robustness and practical relevance of the two-pot retirement savings model through extensive Monte Carlo simulations that replicate salient features of the South African labor market and retirement context. The model incorporates stochastic employment dynamics and investment return volatility, capturing the critical trade-offs faced by workers amid high unemployment and limited liquidity access. Employment transitions are modeled as a two-state Markov chain calibrated with an average job tenure of 3.1 years and an official unemployment rate of 33%, consistent with recent empirical labor market findings (

Old Mutual, 2024;

Pnet, 2024;

Writer, 2022). This approach realistically represents labor market spells over a 40-year working horizon (ages 25 to 65), reflecting episodic employment and unemployment in emerging economies. The calibrated transition probabilities yield long-run steady-state employment and unemployment shares of approximately 67% and 33%, respectively, providing a baseline validation for the simulation outputs.

Retirement contributions occur exclusively during employment periods and are allocated between a liquid pot and a locked pot according to the fraction

p. This setup aligns with South Africa’s legislated two-pot retirement system, mandating restricted access to a portion of savings while permitting limited withdrawals for emergencies (

South African Reserve Bank, 2024). The continuous parameterization of

p allows investigation of the trade-off between short-term liquidity needs and long-term wealth accumulation. Investment returns are modeled as normally distributed with mean 14% and standard deviation 18.8%, based on historical data from the JSE All-Share Index spanning 1996 to 2021 (

Robeco, 2020;

TheGlobalEconomy.com, 2021;

Van Rensburg & Slaney, 2017). Returns are truncated at a -50% lower bound to exclude extreme losses beyond observed market behavior. Consumption during unemployment is floor-limited to 30% of salary to reflect minimum subsistence levels slightly above the Upper-Bound Poverty Line (

Statistics South Africa, 2024a,

2024b).

To determine the welfare-maximizing allocation between the liquid and locked pots, we employ a Monte Carlo simulation calibrated to South African labor market conditions. The simulation explicitly incorporates stochastic employment spells and investment return volatility, reflecting the episodic employment patterns and market uncertainties faced by South African workers.

Key simulation parameters include a 40-year working horizon, an average job tenure of 3.1 years, and an official unemployment rate of 33%, yielding an expected fraction of time spent unemployed consistent with empirical labor market data (

Pnet, 2024;

Writer, 2022). Contributions are 15% of salary, with salaries growing at 1% per year. Investment returns follow a normal distribution with mean 14% and standard deviation 18.8%, truncated at −50% to avoid extreme outliers. Consumption during unemployment is floor-limited to 30% of salary. Lifetime utility is calculated using a Constant Relative Risk Aversion (CRRA) function with risk aversion parameter

and a discount factor of 0.96.

For each liquid allocation fraction p (ranging from 0.1 to 0.5), we simulate 1000 independent career trajectories. In each simulation, the liquid and locked pots evolve according to employment status, contributions, stochastic returns, and withdrawal rules (liquid pot withdrawals capped at 20% per period with a minimum of ZAR 2000). At retirement, total accumulated wealth is annuitized over 20 years to generate annual retirement income, and discounted lifetime utility is aggregated across the working and retirement phases.

The optimal allocation is identified as the fraction of contributions to the liquid pot that maximizes average discounted lifetime utility across all simulations. In our calibrated setting, this procedure yields an optimal allocation of approximately 50%, balancing the need for liquidity during periods of unemployment with the goal of sufficient long-term retirement wealth. Sensitivity analyses show that higher unemployment rates increase the optimal , whereas higher expected investment returns allow for a smaller liquid share, illustrating the trade-off between flexibility and accumulation.

This simulation-based methodology provides a transparent and data-driven justification for the chosen allocation, explicitly linking the model parameters to South Africa’s labor market realities and retirement policy objectives. Moreover, it allows a direct comparison with the existing one-third/two-thirds system, demonstrating that the two-pot design improves lifetime utility while maintaining essential liquidity for households facing episodic income shocks.

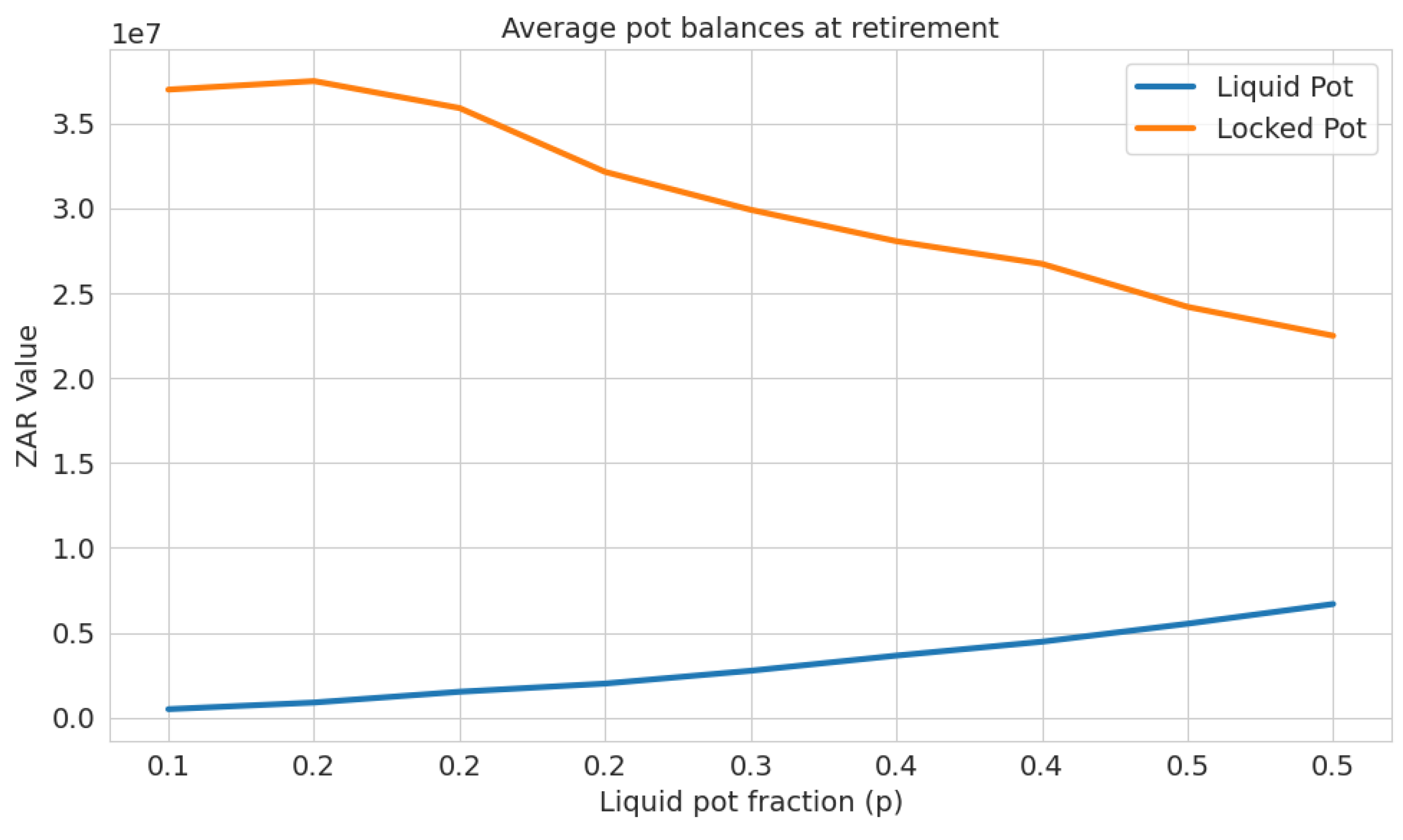

Figure 1 illustrates the average evolution of liquid and locked pot balances over the working life across various liquidity allocations

p. The liquid pot grows more modestly due to withdrawals during unemployment spells, while the locked pot, inaccessible until retirement, accumulates more substantially. This divergence highlights the liquidity–wealth trade-off inherent in the two-pot design. Notably, allocations near

balance access and accumulation effectively.

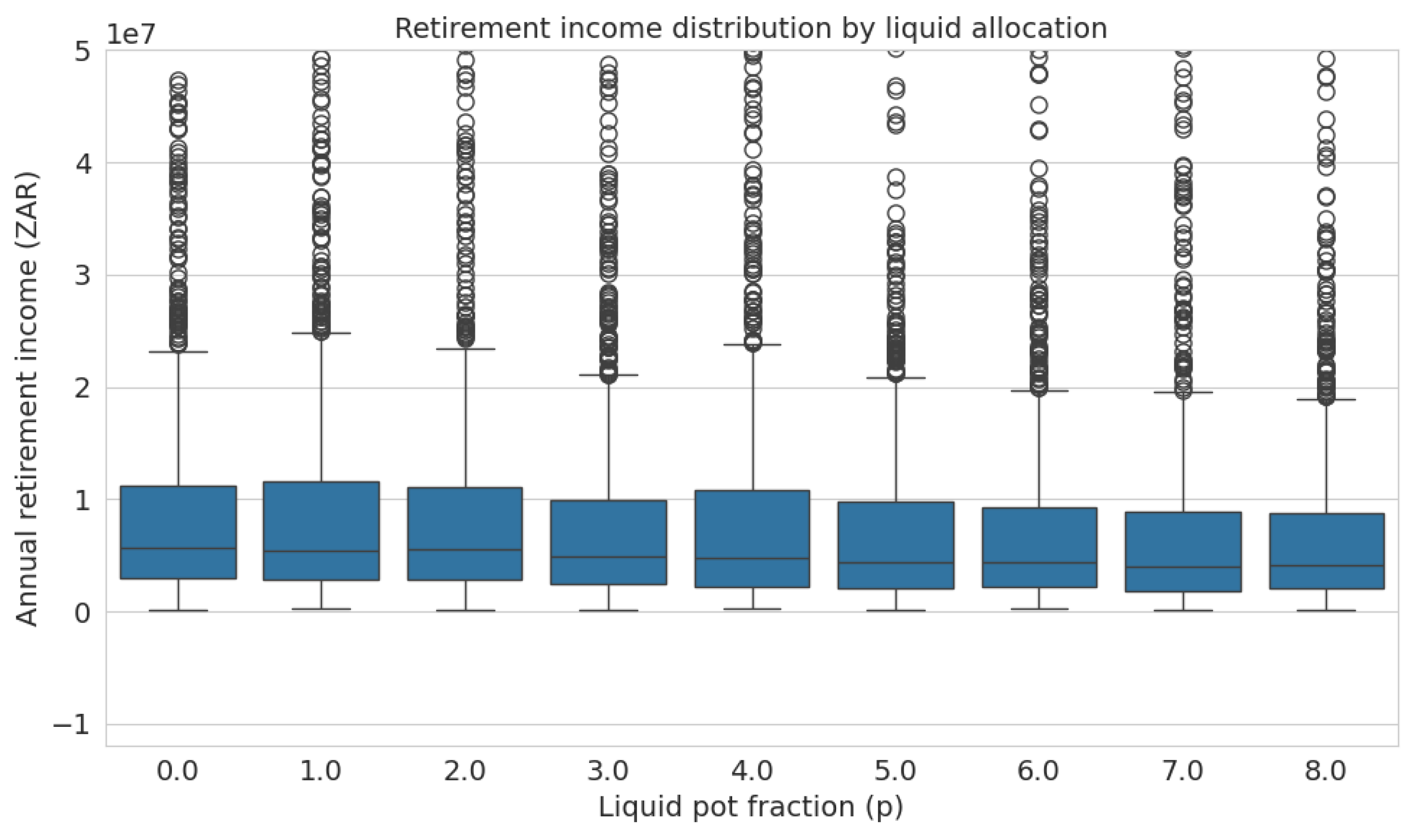

Figure 2 presents the distribution of retirement incomes by liquid pot fraction

p. The model produces higher mean retirement incomes at balanced allocations, with wider distributions reflecting investment return volatility and employment uncertainty. These results confirm that moderate liquidity allocations enable better consumption smoothing and wealth preservation in retirement.

Figure 3 plots discounted lifetime CRRA utility against

p, incorporating consumption during employment, unemployment, and retirement phases. The welfare-maximizing allocation centres around

, consistent with the findings from pot balances and retirement income. Sensitivity analysis reveals that increased unemployment rates push the optimal

p higher, emphasizing the value of accessible funds during frequent employment disruptions. Conversely, higher expected returns allow a reduction in liquidity needs, promoting greater locked pot accumulation.

Our simulation results identify an optimal liquid pot allocation of approximately 50%, which maximizes discounted lifetime utility under South African labor market conditions. At this allocation, the average retirement income reaches around ZAR 7.26 million, with terminal liquid and locked pot balances of approximately ZAR 6.69 million and ZAR 22.5 million, respectively. These figures underscore the substantial wealth accumulation achievable under the two-pot framework while preserving sufficient liquidity for consumption smoothing. To improve interpretability, we also express retirement outcomes as replacement rates relative to South Africa’s median and average formal-sector wages. At the welfare-maximizing allocation of

, the average retirement income corresponds to a replacement rate of 41% relative to the median wage and 36% relative to the average wage. This exceeds the currently observed average replacement rate in South Africa of 25–30% (

National Treasury, 2012) but remains below the international adequacy benchmark of 60%.

Table 1 summarizes these comparisons across liquidity allocations.

Sensitivity analyses reveal that a 10% increase in the unemployment rate raises the optimal liquid allocation by roughly 3%, emphasizing the increased importance of accessible funds amid greater employment instability. Conversely, a 1% increase in expected investment returns allows for a 2% reduction in the liquid fraction, facilitating enhanced wealth accumulation in the locked pot. By framing the outcomes in terms of replacement rates, we show that while the optimal allocation improves lifetime utility, it may still leave households below adequacy benchmarks, underscoring the trade-off between flexibility and sufficiency.

4. Discussion

The limitations of South Africa’s existing pension framework are particularly stark. Under the one-third/two-thirds rule, individuals often withdraw their one-third share as a lump sum upon job separation, which erodes long-term savings and exacerbates old-age poverty. Evidence from the National Treasury indicates that over 90% of members cash out their savings at exit, leaving minimal preservation for retirement (

National Treasury of South Africa, 2021). Such leakage highlights why incremental modifications to the old system were insufficient. The two-pot reform was introduced to enforce partial preservation, while still accommodating strong liquidity needs observed in practice.

This study examines the challenge of designing retirement savings systems that balance the need for liquidity during working life with the goal of adequate income in retirement. The analysis is motivated by these recent reforms, most notably the introduction of the “two-pot” system, within a socioeconomic context marked by high unemployment, unstable employment histories, and widespread pre-retirement withdrawals. Government data indicate that, prior to the reform, over 700,000 individuals annually accessed withdrawal lump sums upon leaving employment, and early administrative records from the two-pot system show that within its first year, a substantial proportion of eligible members drew from their accessible savings pots (

Polity.org.za, 2025). These patterns underscore a strong pre-existing demand for liquidity.

The stochastic two-pot retirement savings model developed here incorporates labor market uncertainty via a Markov chain-based Monte Carlo simulation calibrated to South African conditions. The results indicate that high unemployment and career volatility significantly raise the welfare-maximizing share of contributions allocated to the liquid pot. Under baseline parameters, the optimal allocation is approximately 50%, suggesting that greater liquidity, while reducing average retirement income, can improve lifetime welfare by enabling consumption smoothing during unemployment spells. Retirement income volatility analysis further shows that labor market instability widens the dispersion of retirement outcomes, reinforcing the welfare gains from accessible savings. The results in

Table 1 highlight that even at the welfare-maximizing allocation of

, replacement rates remain below both South Africa’s adequacy thresholds and the international benchmark of 60%. While liquidity access improves household welfare through consumption smoothing, it comes at the cost of reducing long-term income sufficiency. The comparison across allocations also shows that a higher liquidity share (

) further erodes retirement adequacy, despite offering greater flexibility during working life. These findings underscore a central trade-off: South Africa’s two-pot system can enhance resilience to income shocks but may still leave many retirees below adequacy standards unless complemented by higher contribution rates or targeted support mechanisms.

These findings challenge the fixed one-third/two-thirds allocation mandated by the current policy. The close alignment between the model’s optimal liquidity share and the observed withdrawal behavior since the reform’s implementation suggests that the legislated limit may underprovide liquidity for households exposed to frequent income shocks. Sensitivity tests show that a 10% increase in the unemployment rate raises the optimal liquid share by roughly 3%, while a 1% increase in expected investment returns reduces it by about 2%. This interaction between labor market risk and investment performance highlights the value of flexible, adaptive contribution rules that respond to prevailing economic conditions. At the same time, the welfare-maximizing allocation is unlikely to be uniform across all households (

Cesa-Bianchi et al., 2025;

Manurangsi & Suksompong, 2017). Differences in income levels, risk preferences, and participation in the informal sector could meaningfully shift the balance between liquidity and long-term savings. For example, low-income or highly risk-averse workers may require higher liquidity shares to buffer against shocks, whereas higher-income or more stable earners may benefit from committing a greater fraction to locked retirement assets. Informal-sector workers, who face irregular contributions and weaker institutional coverage, may place disproportionate value on immediate accessibility (

Prasad et al., 2025). While such heterogeneity is not explicitly modeled here, recognizing it underscores the importance of tailoring system design to South Africa’s highly unequal labor market.

Beyond South Africa, it is instructive to compare international approaches to liquidity access in retirement systems.

Table 2 summarizes key withdrawal and flexibility rules in selected countries. The comparison highlights how different jurisdictions balance short-term access with long-term adequacy, situating the South African two-pot reform within the broader landscape of global pension design.

5. Conclusions

The analysis demonstrates that aligning pension design with labor market realities can enhance both retirement security and overall welfare, particularly in economies with high employment volatility. By quantifying the welfare implications of varying liquidity allocations, the model provides evidence that the optimal share of accessible savings can differ substantially from fixed policy prescriptions, especially when unemployment risk is elevated. The integration of empirical withdrawal patterns into the assessment strengthens the case for more flexible allocation frameworks.

From a policy perspective, these findings point toward the value of adaptive contribution rules that adjust the split between liquid and locked savings in response to prevailing conditions (

Bufe et al., 2022). For example, higher unemployment rates could automatically raise the liquid allocation, while periods of strong investment performance might allow for a lower liquid share to promote long-term accumulation (

Despard et al., 2018;

Gjertson, 2016). Such adaptive mechanisms would align the system more closely with household risk exposures, rather than relying on a fixed statutory rule.

Furthermore, targeted flexibility for vulnerable groups such as low-income workers, those in precarious employment, or informal-sector participants could improve equity by recognizing heterogeneous needs. Linking contribution rules to household characteristics, while administratively complex, would help ensure that the two-pot system provides both adequate consumption smoothing and sustainable retirement incomes. Importantly, our simulations indicate that the proposed two-pot system with an optimal liquid allocation of approximately 50% yields higher discounted lifetime utility compared to the existing one-third/two-thirds policy. Under the current system, frequent cash-outs at job separation reduce long-term wealth and limit consumption smoothing, resulting in lower lifetime utility. By contrast, the two-pot design preserves a portion of savings while allowing necessary liquidity, enabling households to better navigate employment volatility and achieve improved welfare outcomes. This direct comparison reinforces the practical and policy relevance of adopting adaptive or differentiated contribution rules.

These proposals build directly on the model’s empirical insights: The optimal allocation shifts systematically with unemployment and investment conditions, while heterogeneity in risk and earnings trajectories suggests that a uniform allocation may not maximize welfare across the population. By moving toward adaptive and differentiated contribution frameworks, South Africa’s pension system could more effectively balance liquidity and adequacy in practice.

Future research could extend the model by introducing heterogeneity in individual characteristics such as risk aversion, financial literacy, and earnings trajectories, as well as by explicitly incorporating the informal sector, which is a substantial part of South Africa’s labor market. Moreover, incorporating additional macroeconomic shocks, including inflationary spikes and systemic financial crises, would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the interaction between liquidity access, asset returns, and welfare outcomes. Such enhancements would increase the model’s applicability to broader policy contexts and deepen its relevance to retirement system design.