Maternity Leave Reform and Women’s Labor Outcomes in Colombia: A Synthetic Control Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Empirical Strategy and Data

3.1. Empirical Strategy

3.2. Data

4. Results

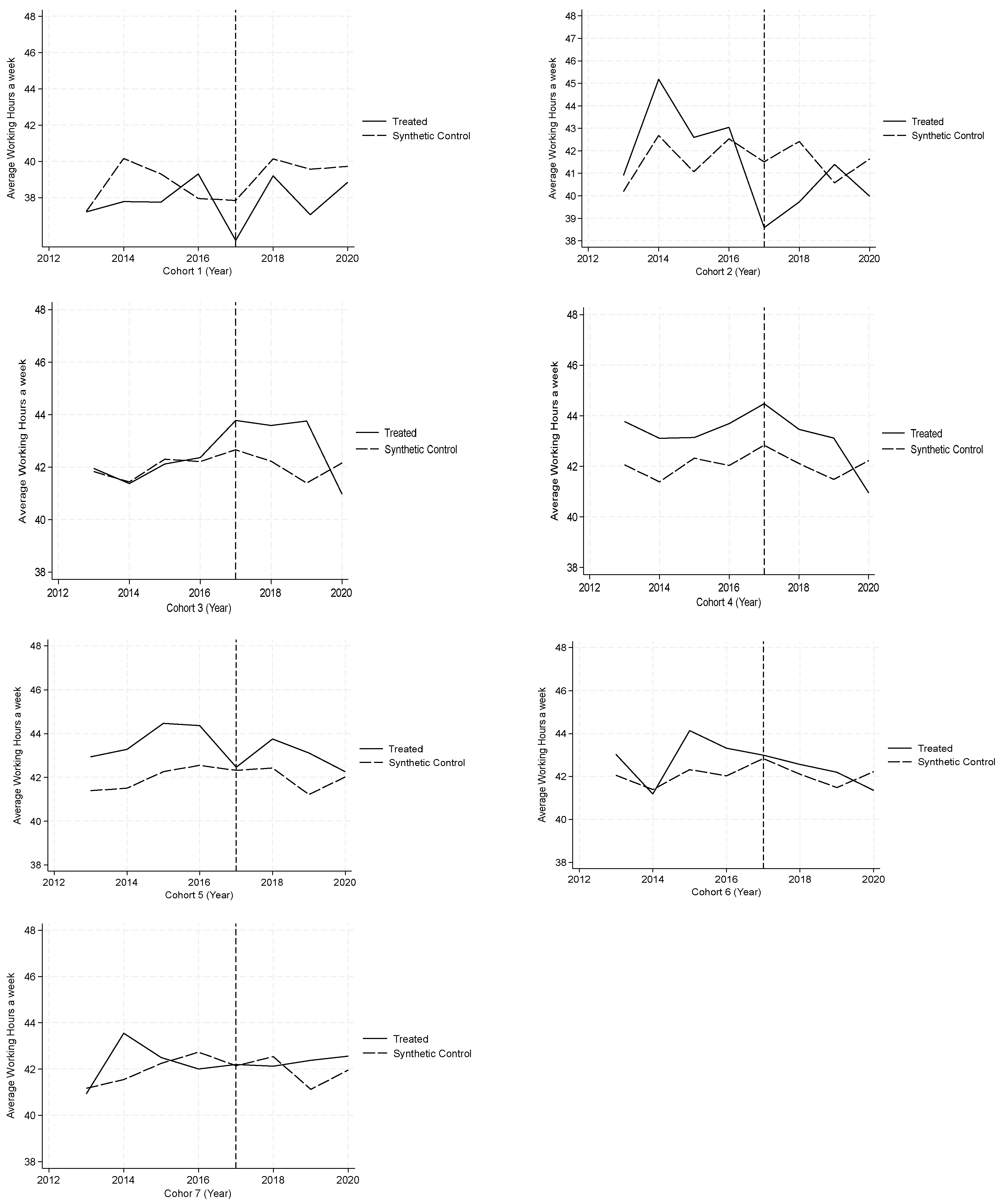

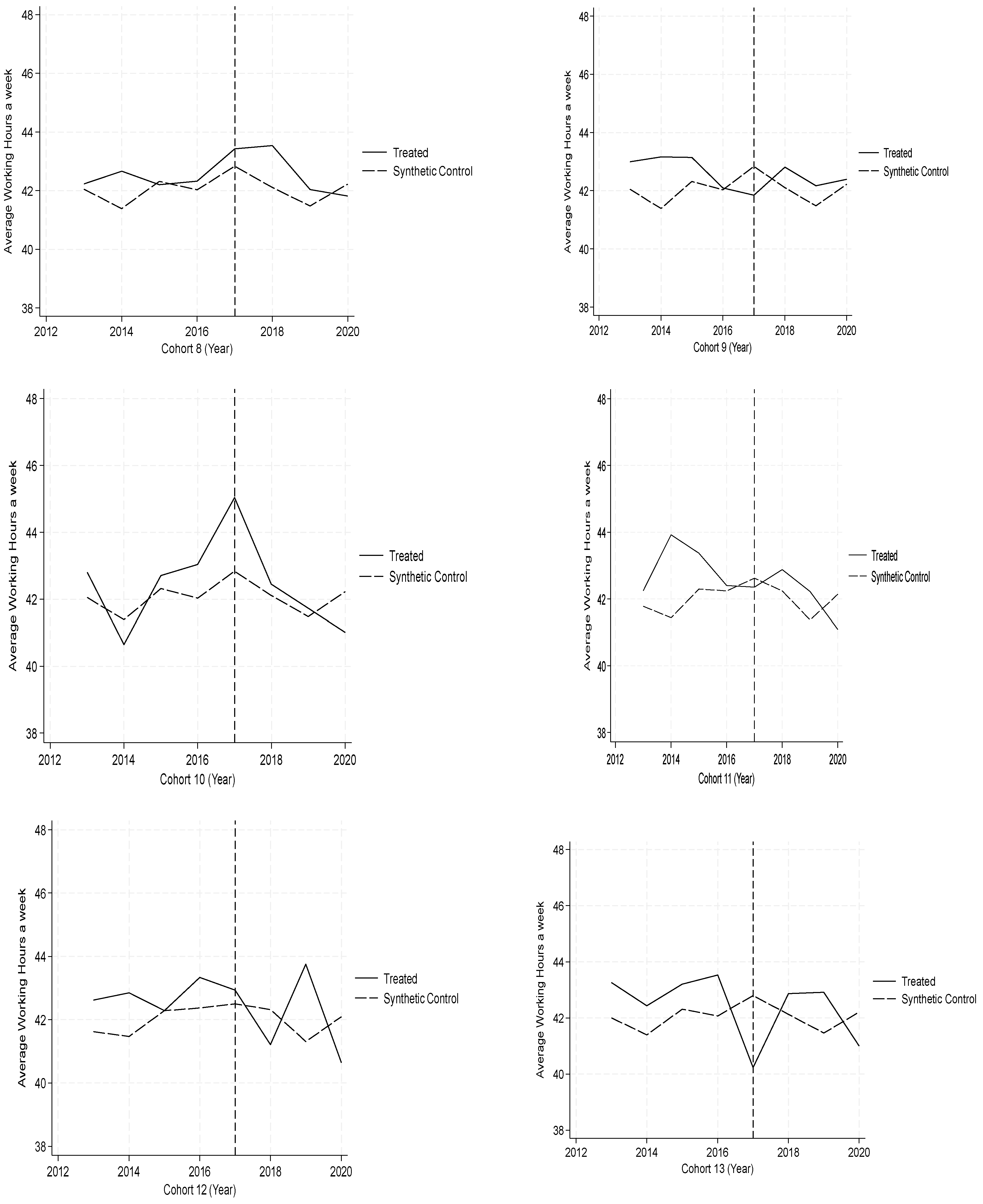

4.1. Quantity Effects

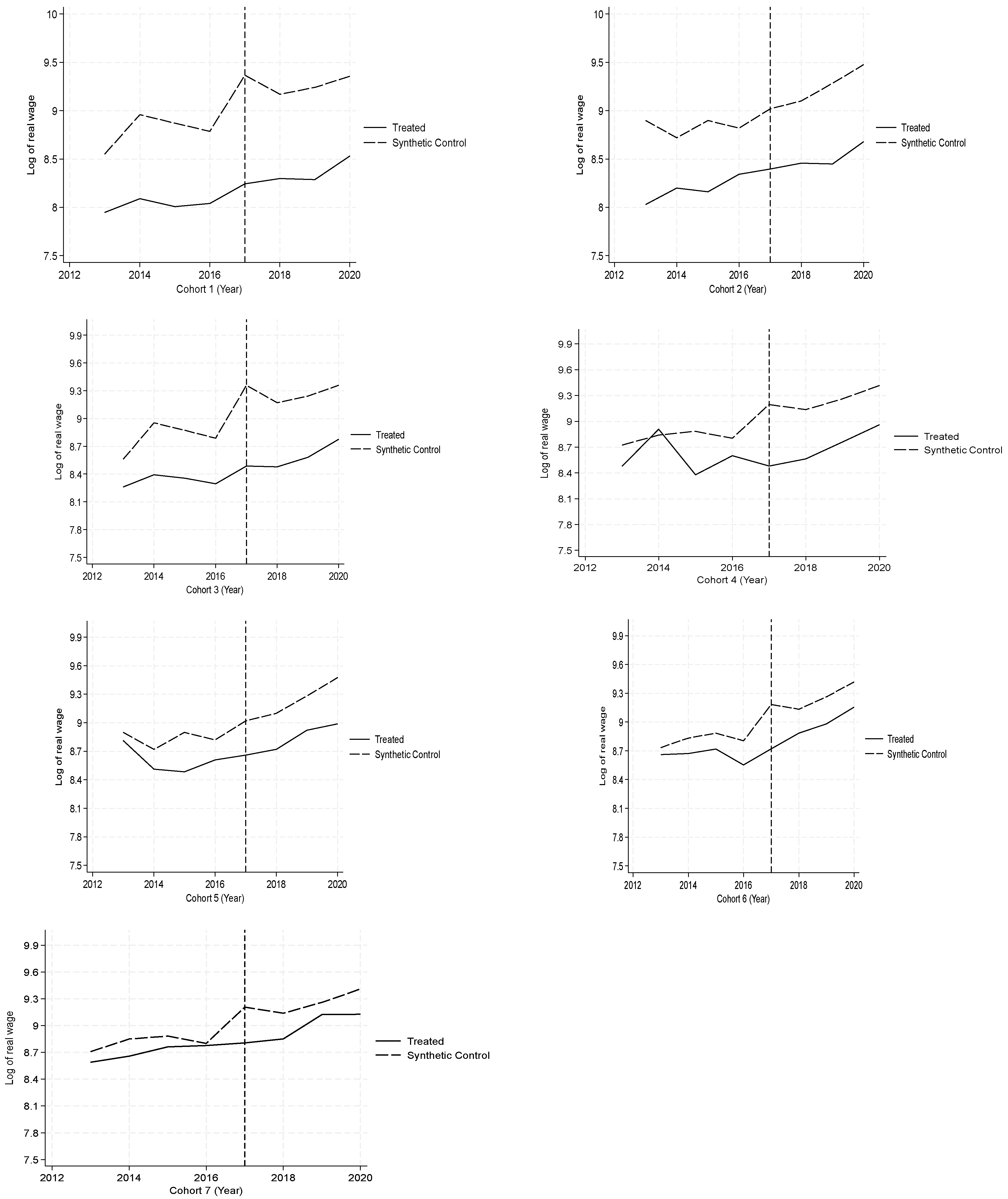

4.2. Price Effects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

| 1 | In Colombia, the minimum age of formal employment is 18 years and the pension age is stipulated by law to 57 years for women. |

| 2 | We compute the post-Law period differences,

, for each treated cohort j in period t. Later, we aggregate the estimates to the national cohort level, , where N is 13 treated cohort (18 to 43 years old). We perform Chu and Townsend’s (2019) placebo permutation to make an inference. We compute placebo effects, , in each treated cohort j using each cohort in the control group g. Then, we randomly select one cohort placebo effect, (i), from each treated cohort, to obtain an average national-cohort placebo effect as . In order to discuss the statistical significance, we repeat this procedure two million times such that If the distribution of placebo effects yields several large effects as , then the estimated impact is likely observed by chance. Moreover, Galiani and Quistorff (2017) warned placebo permutations may generate high p-values with bad match quality units in the pre-intervention period. Therefore, we also calculate p-values using units below the 75th percentile root mean squared predictor error (RMSPE). |

| 3 | Given the difficulty of observing the years of real experience, the potential experience measured as “age − years education − 6” is used as a proxy variable. |

| 4 | Natural log of hourly wages. |

| 5 | The negative value implies that women earn more than men. For example, while women between the ages of 15 and 24 years old earn $4400 COP, a man earns $4100 nominal COP (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [DANE], 2020). |

References

- Abadie, A. (2021). Using synthetic controls: Feasibility, data requirements, and methodological aspects. Journal of Economic Literature, 59(2), 391–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105(490), 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addati, L., Cassirer, N., & Gilchrist, K. (2014). Maternity and paternity at work: Law and practice across the world. International Labour Office. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/maternity-and-paternity-work-law-and-practice-across-world (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Agüero, J. M., & Marks, M. S. (2011). Motherhood and female labor supply in the developing world: Evidence from infertility shocks. Journal of Human Resources, 46(4), 800−826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arando Lasagabaster, S., & Lekuona Agirretxe, A. (2025). The gender pay gap in shared-ownership firms: Determinants, variation and parity-seeking measures. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M., & Milligan, K. (2008a). How does job-protected maternity leave affect mothers’ employment? Journal of Labor Economics, 26(4), 655–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M., & Milligan, K. (2008b). Maternal employment, breastfeeding, and health: Evidence from maternity leave mandates. Journal of Health Economics, 27(4), 871–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berniell, I., Berniell, L., De la Mata, D., Edo, M., & Marchionni, M. (2021). Gender gaps in labor informality: The motherhood effect. Journal of Development Economics, 150, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berniell, I., Berniell, L., de la Mata, D., Edo, M., & Marchionni, M. (2023). Motherhood and flexible jobs: Evidence from Latin American countries. World Development, 167, 106225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3), 789–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botello, H., & Guerrero, I. (2020). Las leyes de licencia de maternidad y el mercado laboral en Colombia [Maternity leave laws and the labor market in Colombia]. Economía & Región, 13(1), 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Botello, H., & López, A. (2014). El efecto de la maternidad sobre los salarios femeninos en Latinoamérica [The effect of motherhood on women’s wages in Latin America]. Semestre Económico, 17(36), 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaan, S., Rosenbaum, P., Lassen, S., & Steingrimsdottir, H. (2022). Maternity leave and paternity leave: Evidence on the economic impact of legislative changes in high income countries. IZA DP No. 15129. IZA—Institute of Labor Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, P., Vidal, C., Rojas, E., Zárate, C., & Sandaña, C. (2021). Maternal leave extension effect on breastfeeding according to poverty, Chile 2008–2018. Andes Pediatría, 92(4), 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Núñez, R. B., Santero-Sánchez, R., & de Castro Romero, L. (2025). The role of the social economy as a transformative agent in labour markets: Contribution to the reduction of gender gaps in job quality. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.-W. L., & Townsend, W. (2019). Joint culpability: The effects of medical marijuana laws on crime. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 159, 502–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, R. K., McGovern, P. M., & Dowd, B. E. (2014). Maternity leave duration and postpartum mental and physical health: Implications for leave policies. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 39(2), 369–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [DANE]. (2020). Brecha salarial en Colombia. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/notas-estadisticas/nov-2020-brecha-salarial-de-genero-colombia.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Dussuet, A., & Gasté, L. (2024). Gender, SSE and French public policies for ageing at home. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, J. P., Fernandez, J., & Lauer, C. (2023). Effects of maternity on labor outcomes and employment quality for women in Chile. Journal of Applied Economics, 26(1), 2232965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [ECLAC], UN Women & International Labour Organization [ILO]. (2025). The right to care in Latin America and the Caribbean: Progress on the regulatory front. ECLAC/UN Women/ILO. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/82268-right-care-latin-america-and-caribbean-progress-regulatory-front (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Fajardo Hoyos, C. L., & Mora Rodríguez, J. J. (2024). Effect of home care activities on labor participation in a developing country. Economics and Sociology, 17(1), 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero de Saade, M. T., Cañón, L., & Pineda, J. A. (1991). Participación de la mujer en el trabajo. Mujer trabajadora. Nuevo compromiso social [Women’s participation in the workplace. Working women. A new social commitment]. Estudios Sociales Juan Pablo II. ISBN 9589540015. [Google Scholar]

- Galiani, S., & Quistorff, B. (2017). The synth_runner package: Utilities to automate synthetic control estimation using synth. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 17(4), 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, E., Parada, C., Querejeta, M., & Salvador, S. (2024). Gender gaps and family leaves in Latin America. Review of Economics of the Household, 22(2), 387–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, L. F., & Zuluaga, B. (2013). Is there a motherhood penalty? Decomposing the family wage gap in Colombia. Journal of Family and Economics Issues, 34(4), 412–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J. M., Ibarra-Ortega, A., Hernández-Cordero, S., González de Cossío, T., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2024). Breastfeeding among women employed in Mexico’s informal sector: Strategies to overcome key barriers. International Journal for Equity in Health, 23, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornick, J., Meyers, M., & Ross, K. (1970). Public policies and the employment of mothers: A cross-national study. Social Science Quarterly, 79(1), 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gregg, P., Gutiérrez-Domènech, M., & Waldfogel, J. (2007). The employment of married mothers in Great Britain, 1974–2000. Economica, 74(296), 842–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbau Albert, M. (2021). The impact of health status and human capital formation on regional performance: Empirical evidence. Papers in Regional Science, 100(1), 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanratty, M., & Trzcinski, E. (2009). Who benefits from paid family leave? Impact of expansions in Canadian paid family leave on maternal employment and transfer income. Journal of Population Economics, 22(3), 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimzade, N. (2020). Endogenous preferences for parenting and macroeconomic outcomes. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 172, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegewisch, A., & Gornick, J. (2011). The impact of work-family policies on women’s employment: A review of research from OECD countries. Community, Work &Family, 14(2), 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internacional Labor Organization [ILO]. (2018). El trabajo de cuidados y los trabajadores del cuidado para un futuro con trabajo decente [Care work and care workers for a decent working future]. Internacional Labor Organization. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. (2018). ILOSTAT database [online]. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Jaumotte, F. (2003). Female labour force participation: Past trends and main determinants in OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 376. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K., & Wilcher, B. (2023). Reducing maternal labor market detachment: A role for paid family leave. Labour Economics, 87, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerman, J. A., & Leibowitz, A. (1999). Job continuity among new mothers. Demography, 36(2), 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleven, H., Landais, C., & Søgaard, J. E. (2019). Children and gender inequality: Evidence from Denmark. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(4), 181–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalive, R., Schlosser, A., Steinhauer, A., & Zweimüller, J. (2013). Parental leave and mothers’ careers: The relative importance of job protection and cash benefits. The Review of Economic Studies, 81(1), 219–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalive, R., & Zweimüller, J. (2009). How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1363–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., & Buzzanell, P. M. (2004). Negotiating maternity leave expectations: Perceived tensions between ethics of justice and care: Perceived tensions between ethics of justice and care. The Journal of Business Communication (1973), 41(4), 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E., Wu, L., Yang, W., & Xu, S. (2021). Hotel work-family support policies and employees’ needs, concerns and Challenges—The case of working mothers’ maternity leave experience. Tourism Management, 83, 104216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C., & Pinho Neto, V. (2018). The labor market effects of maternity leave extension. Comparative Political Economy: Social Welfare Policy eJournal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C., Pinho Neto, V., & Szerman, C. (2024). Firm and worker responses to extensions in paid maternity leave. Journal of Human Resources, 0322-12232R2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cárdenas, B., Cote-Rangel, Ó., Dueñas, Z., & Camacho-Ramírez, A. (2017). Telecommuting: A new option to increase maternity leave in Colombia. Revista de Derecho, 48, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. (2025). Maternity leave. Merriam-Webster. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/maternity%20leave (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Misra, J., Budig, M., & Boeckmann, I. (2011). Work-family policies and the effects of children on women’s employment hours and wages. Community, Work & Family, 14(2), 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinos, C. (2012). La Ley de protección a la maternidad como incentivo de participación laboral femenina: El caso colombiano [The Maternity Protection Law as an incentive for female labor participation: The Colombian case]. Coyuntura Económica: Investigación Económica y Social, XLll(1), 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, F. R., Buccini, G. D. S., Venâncio, S. I., & da Costa, T. H. M. (2017). Influence of maternity leave on exclusive breastfeeding. Jornal de Pediatria, 93(5), 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J. J., Herrera, D. Y., & Álvarez, J. F. (2021). Pandemia y duración del desempleo juvenil en Cali [Pandemic and duration of youth unemployment in Cali]. Revista de Economía Institucional, 24(46), 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J. J., & Muro, J. (2017). Dynamic effects of the minimum wage on informality in Colombia. Labour, 31(1), 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K., & Zippel, K. (2003). Paid to care: The origins and effects of care leave policies in Western Europe. Social Politics, 10, 49–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Rosenblatt, D., Benmarhnia, T., Bedregal, P., López-Arana, S., Rodríguez-Osiac, L., & Garmendia, M. L. (2023). The impact of health policies and the COVID-19 pandemic on exclusive breastfeeding in Chile during 2009–2020. Scientific Reports, 13, 10671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunga, S. A., Odero, H. O., Syonguvi, J., Mbuthia, M., Tanaka, S., Kiwuwa-Muyingo, S., & Kadengye, D. T. (2024). “Our program manager is a woman for the first time”: Perceptions of health managers on what workplace policies and practices exist to advance women’s career progression in the health sector in Kenya. International Journal for Equity in Health, 23, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olarte, L., & Peña, X. (2010). El efecto de la maternidad sobre los ingresos femeninos [The effect of childbearing on women’s incomes]. Ensayos Sobre Política Económica, 28(63), 190–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, X., Cárdenas, J. C., Ñopo, H., Castañeda, J. L., Muñoz, J. S., & Uribe, C. (2013). Mujer y movilidad social [Women and social mobility] (Artículos CEDE). Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Economía, CEDE. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, B., & Hook, J. L. (2005). The Structure of Women’s Employment in Comparative Perspective. Social Forces, 84(2), 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, B., & Hook, J. L. (2009). Gendered tradeoffs: Family, social policy, and economic inequality in twenty-one countries. Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 978-0-87154-695-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, N. (2019). A mí me gustaría, pero en mis condiciones no puedo: Maternidad, discriminación y exclusión en el mercado laboral colombiano [“I would like to, but in my conditions I can’t”: Maternity, discrimination and exclusion in the Colombian labor market]. Revista CS, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, N., Tribin, A. M., & Vargas, C. (2015). Maternity and labor markets: Impact of legislation in Colombia. IDB Working Paper Series 583. Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Rege, M., & Solli, I. F. (2013). The impact of paternity leave on fathers’ future earnings. Demography, 50(6), 2255–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J. E. (2018). La maternidad y el empleo formal en Colombia [Maternity and formal employment in Colombia]. Artículos de trabajo sobre economía regional y urbana, 268. Banco de la República de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, R. A. (1996). Women’s work histories. Population and Development Review, 22, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossin, M. (2011). The effects of maternity leave on children’s birth and infant health outcomes in the United States. Journal of Health Economics, 30(2), 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossin-Slater, M. (2017). Maternity and family leave policy. NBER working paper No. w23069. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2903736 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Rönsen, M., & Sundström, M. (1996). Maternal employment in Scandinavia: A comparison of the after-birth employment activity of Norwegian and Swedish women. Journal of Population Economics, 9(3), 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhm, C. J. (1998). The economic consequences of parental leave mandates: Lessons from Europe. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(1), 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönberg, U., & Ludsteck, J. (2014). Expansions in maternity leave coverage and mothers’ labor market outcomes after childbirth. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(3), 469–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehelin, K., Bertea, P. C., & Stutz, E. Z. (2007). Length of maternity leave and health of mother and child—A review. International Journal of Public Health, 52, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- StataCorp. (2023). Stata: Release 18 [Statistical software]. StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Thévenon, O. (2011). Family policies in OECD countries: A comparative analysis. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, A. M. T., Vargas, C. O., & Bustamante, N. R. (2019). Unintended consequences of maternity leave legislation: The case of Colombia. World Development, 122, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, M. S., Bhatia, R., Riano, N. S., de Faria, L., Catapano-Friedman, L., Ravven, S., Weissman, B., Nzodom, C., Alexander, A., Budde, K., & Mangurian, C. (2020). The impact of paid maternity leave on the mental and physical health of mothers and children. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 28(2), 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldfogel, J. (1998). Understanding the “family gap” in pay for women with children. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(1), 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2024). Women, business and the law 2024. World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2018, September 25). Salud de la mujer [Women’s health]. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/women-s-health#:~:text=Mujeres%20en%20edad%20reproductiva%20 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- World Justice Project. (2024). Rule of law index 2024. World Justice Project. Available online: https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/downloads/WJPIndex2024.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

| Year | Variable | Cohort [Age Group] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [18–19] | 2 [20–21] | 3 [22–23] | 4 [24–25] | 5 [26–27] | 6 [28–29] | 7 [30–31] | 8 [32–33] | 9 [34–35] | 10 [36–37] | 11 [38–39] | 12 [40–41] | 13 [42–43] | ||

| 2017 | Hours worked | 35.64 | 38.59 | 43.77 | 44.47 | 42.47 | 43.00 | 42.20 | 43.43 | 41.85 | 45.04 | 42.35 | 42.93 | 40.23 |

| Real hourly wage (COP) | 3804.71 | 4436.57 | 4856.97 | 4826.67 | 5776.16 | 6140.37 | 6678.99 | 5962.12 | 5689.99 | 6965.06 | 8083.04 | 7694.95 | 9559.75 | |

| Real hourly wage (USD) | 0.84 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.28 | 1.36 | 1.48 | 1.32 | 1.26 | 1.54 | 1.79 | 1.70 | 2.11 | |

| Years of education | 10.61 | 11.35 | 12.26 | 12.71 | 12.3 | 12.63 | 12.21 | 11.83 | 11.52 | 12.2 | 12.23 | 10.99 | 11.73 | |

| Head household (%) | 4.13 | 11.24 | 14.55 | 18.37 | 22.57 | 26.15 | 29.93 | 36.2 | 38.97 | 35.55 | 32.6 | 37.41 | 38.84 | |

| Children under 2 (%) | 29.61 | 30.04 | 31.22 | 27.02 | 30.51 | 24.49 | 20.40 | 17.14 | 19.70 | 18.81 | 14.51 | 14.09 | 13.05 | |

| Informality (%) | 76.45 | 64.14 | 48.46 | 46.89 | 49.9 | 43.48 | 53.24 | 54.83 | 71.66 | 54.75 | 51.83 | 56.87 | 54.12 | |

| Economic activity—Manufacturing Industries (%) | 9.65 | 11.31 | 5.84 | 18.13 | 7.73 | 5.05 | 13.61 | 10.36 | 16.60 | 7.01 | 9.70 | 4.82 | 4.77 | |

| Economic activity—Wholesale and Retail Trade; Repair of Motor Vehicles and Motorcycles (%) | 8.00 | 13.77 | 13.77 | 7.84 | 10.80 | 12.88 | 13.57 | 17.76 | 18.43 | 16.73 | 11.23 | 12.80 | 11.70 | |

| Economic activity—Accommodation and Food Services (%) | 10.11 | 17.93 | 6.21 | 3.02 | 7.32 | 11.28 | 6.17 | 9.92 | 5.41 | 5.85 | 11.29 | 10.02 | 4.24 | |

| Economic activity—Activities of Extraterritorial Organizations and Entities (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.35 | |

| Mother educ. (%) | 1.76 | 5.08 | 4.35 | 5.96 | 6.69 | 7.27 | 6.77 | 6.38 | 3.78 | 6.14 | 8.16 | 5.29 | 3.38 | |

| 2018 | Hours worked | 39.20 | 39.73 | 43.58 | 43.46 | 43.75 | 42.57 | 42.12 | 43.54 | 42.81 | 42.45 | 42.88 | 41.21 | 42.87 |

| Real hourly wage (COP) | 4020.91 | 4716.88 | 4805.36 | 5241.21 | 6129.10 | 7232.31 | 6985.96 | 9157.73 | 10,500.17 | 8648.16 | 10,859.32 | 9360.07 | 9767.59 | |

| Real hourly wage (USD) | 0.89 | 1.04 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.36 | 1.60 | 1.54 | 2.02 | 2.32 | 1.91 | 2.40 | 2.07 | 2.16 | |

| Years of education | 10.15 | 11.03 | 11.87 | 12.69 | 12.84 | 12.7 | 12.48 | 12.61 | 12.37 | 12.33 | 12.06 | 11.22 | 11.17 | |

| Head household (%) | 4.38 | 11.82 | 13.59 | 16.84 | 22.4 | 24.95 | 26.48 | 29.72 | 27.8 | 31.35 | 33.81 | 34.08 | 36.66 | |

| Children under 2 (%) | 26.30 | 30.76 | 32.18 | 28.84 | 29.28 | 28.01 | 25.79 | 21.74 | 17.68 | 18.98 | 16.22 | 15.69 | 11.81 | |

| Informality (%) | 84.5 | 64.26 | 47.94 | 44.78 | 42.79 | 47.13 | 52.78 | 50.18 | 50.14 | 47.23 | 51.07 | 55.02 | 55.12 | |

| Economic activity—Manufacturing Industries (%) | 7.46 | 9.76 | 10.12 | 10.81 | 9.78 | 9.81 | 10.04 | 9.21 | 9.56 | 10.86 | 10.23 | 10.17 | 9.67 | |

| Economic activity—Wholesale and Retail Trade; Repair of Motor Vehicles and Motorcycles (%) | 21.95 | 21.85 | 19.76 | 20.14 | 19.76 | 19.95 | 19.29 | 18.32 | 17.94 | 17.37 | 17.51 | 16.58 | 16.39 | |

| Economic activity—Accommodation and Food Services (%) | 11.20 | 10.15 | 7.46 | 6.55 | 6.27 | 6.15 | 5.71 | 5.93 | 5.39 | 6.24 | 6.04 | 5.47 | 5.76 | |

| Economic activity—Activities of Extraterritorial Organizations and Entities (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | |

| Mother educ. (%) | 2.68 | 5.08 | 5.22 | 5.16 | 6.88 | 6.7 | 6.18 | 7.98 | 5.78 | 6.57 | 7.28 | 6.52 | 5.33 | |

| 2019 | Hours worked | 37.05 | 41.39 | 43.76 | 43.12 | 43.12 | 42.20 | 42.37 | 42.04 | 42.17 | 41.73 | 42.23 | 43.75 | 42.92 |

| Real hourly wage (COP) | 3970.69 | 4671.58 | 5330.08 | 6377.38 | 7496.60 | 7954.10 | 9195.22 | 8724.54 | 11,055.75 | 9780.15 | 9762.07 | 8484.73 | 10,421.61 | |

| Real hourly wage (USD) | 0.88 | 1.03 | 1.18 | 1.41 | 1.66 | 1.76 | 2.03 | 1.93 | 2.44 | 2.16 | 2.16 | 1.88 | 2.30 | |

| Years of education | 10.41 | 11.41 | 12.22 | 12.69 | 13.24 | 12.57 | 13.06 | 12.71 | 12.37 | 12.3 | 12.2 | 11.44 | 11.43 | |

| Head household (%) | 7.36 | 10.19 | 14.38 | 18.81 | 22.19 | 27.05 | 29.34 | 29.36 | 29.33 | 33.85 | 34.97 | 34.97 | 41.84 | |

| Children under 2 (%) | 22.64 | 28.38 | 28.01 | 27.30 | 25.92 | 23.62 | 22.47 | 22.87 | 18.14 | 15.44 | 15.66 | 13.15 | 8.99 | |

| Informality (%) | 80.45 | 57.03 | 49.29 | 45.7 | 41.62 | 48.87 | 45.74 | 48.81 | 52.83 | 52.79 | 50.71 | 57.27 | 52.68 | |

| Economic activity—Manufacturing Industries (%) | 7.82 | 10.50 | 10.64 | 11.20 | 11.22 | 11.88 | 12.57 | 10.99 | 10.49 | 10.47 | 10.58 | 9.58 | 12.65 | |

| Economic activity—Wholesale and Retail Trade; Repair of Motor Vehicles and Motorcycles (%) | 20.74 | 20.95 | 21.31 | 19.88 | 19.33 | 18.99 | 15.82 | 15.12 | 18.12 | 17.93 | 18.22 | 16.96 | 16.04 | |

| Economic activity—Accommodation and Food Services (%) | 10.64 | 9.74 | 8.34 | 9.28 | 6.45 | 6.63 | 5.77 | 5.67 | 6.51 | 5.88 | 5.79 | 6.80 | 5.40 | |

| Economic activity—Activities of Extraterritorial Organizations and Entities (%) | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Mother educ. (%) | 4.44 | 3.71 | 4.45 | 7.32 | 5.33 | 6.72 | 8.16 | 6.62 | 7.01 | 5.84 | 6.55 | 4.02 | 3.7 | |

| 2020 | Hours worked | 38.83 | 39.98 | 40.97 | 40.95 | 42.27 | 41.35 | 42.56 | 41.82 | 42.39 | 41.01 | 41.10 | 40.64 | 41.00 |

| Real hourly wage (COP) | 5076.55 | 5877.60 | 6480.46 | 7792.41 | 8011.05 | 9472.22 | 9216.70 | 12,513.85 | 10,293.68 | 13,938.34 | 14,379.21 | 10,157.28 | 11,453.20 | |

| Real hourly wage (USD) | 1.12 | 1.30 | 1.43 | 1.72 | 1.77 | 2.09 | 2.04 | 2.77 | 2.28 | 3.08 | 3.18 | 2.25 | 2.53 | |

| Years of education | 10.36 | 11.54 | 12.41 | 12.9 | 13.12 | 12.98 | 12.87 | 12.62 | 12.52 | 12.46 | 11.89 | 12.18 | 11.54 | |

| Head household (%) | 4.37 | 9.84 | 12.84 | 20.26 | 20.75 | 26.6 | 32.01 | 32.05 | 32.47 | 33.64 | 37.82 | 40.31 | 40.83 | |

| Children under 2 (%) | 19.85 | 26.27 | 26.33 | 24.86 | 28.07 | 25.77 | 20.64 | 20.76 | 16.39 | 13.55 | 12.63 | 12.73 | 8.95 | |

| Informality (%) | 86.93 | 57.80 | 52.81 | 49.46 | 45.34 | 40.73 | 51.18 | 49.28 | 47.3 | 49.85 | 52.92 | 57.19 | 55.85 | |

| Economic activity—Manufacturing Industries (%) | 10.88 | 10.10 | 10.39 | 9.68 | 9.40 | 10.98 | 10.13 | 11.46 | 11.42 | 11.09 | 9.09 | 11.06 | 9.99 | |

| Economic activity—Wholesale and Retail Trade; Repair of Motor Vehicles and Motorcycles (%) | 20.01 | 22.43 | 21.18 | 19.98 | 20.16 | 18.36 | 20.61 | 18.00 | 17.65 | 17.41 | 16.77 | 19.11 | 17.28 | |

| Economic activity—Accommodation and Food Services (%) | 7.69 | 6.33 | 7.02 | 5.98 | 6.06 | 5.20 | 5.52 | 4.89 | 5.10 | 6.08 | 5.03 | 5.14 | 5.40 | |

| Economic activity—Activities of Extraterritorial Organizations and Entities (%) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Mother educ. (%) | 2.31 | 3.32 | 5.23 | 5.4 | 3.84 | 5.2 | 6.05 | 5.94 | 6.55 | 5.21 | 7.04 | 5.14 | 4.53 | |

| Log of Real Wages | Hours Worked | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | Age | 2013–2016 | 2017–2020 | 2013–2016 | 2017–2020 |

| 1 | 18–19 | 8.0230 | 8.3410 | 38.0120 | 37.6800 |

| 2 | 20–21 | 8.1843 | 8.4962 | 42.9282 | 39.9210 |

| 3 | 22–23 | 8.3268 | 8.5808 | 41.9479 | 43.0199 |

| 4 | 24–25 | 8.5920 | 8.6919 | 43.4233 | 43.0009 |

| 5 | 26–27 | 8.6056 | 8.8232 | 43.7651 | 42.9007 |

| 6 | 28–29 | 8.6511 | 8.9366 | 42.9163 | 42.2802 |

| 7 | 30–31 | 8.6971 | 8.9784 | 42.2426 | 42.3132 |

| 8 | 32–33 | 8.7755 | 9.0810 | 42.3560 | 42.7063 |

| 9 | 34–35 | 8.7919 | 91.139 | 42.8523 | 42.3057 |

| 10 | 36–37 | 8.8617 | 9.1612 | 42.2982 | 42.5594 |

| 11 | 38–39 | 8.7849 | 9.2625 | 42.9875 | 42.1393 |

| 12 | 40–41 | 8.7437 | 9.0911 | 42.7723 | 42.1335 |

| 13 | 42–43 | 8.9123 | 9.2375 | 43.1095 | 41.7553 |

| 14 | 44–45 | 8.8348 | 9.2205 | 41.9483 | 42.1629 |

| 15 | 46–47 | 8.8592 | 9.1288 | 41.8642 | 41.4870 |

| 16 | 48–49 | 8.8666 | 9.2042 | 41.0828 | 41.4302 |

| 17 | 50–51 | 8.9348 | 9.2373 | 41.0108 | 41.0708 |

| 18 | 52–53 | 8.7926 | 9.2840 | 40.3901 | 40.5872 |

| 19 | 54–55 | 8.8324 | 9.3856 | 39.6880 | 39.3070 |

| 20 | 56–57 | 8.8384 | 9.3348 | 37.7330 | 38.6866 |

| Average Treatment Effects | ATE1 | −0.239 *** (0.045) | −0.349 *** (0.055) | 1.901 *** (0.446) | 1.225 *** (0.375) |

| ATE2 | −0.172 *** (0.048) | −0.304 *** (0.056) | 1.714 *** (0.523) | 0.917 ** (0.390) | |

| Cohort | Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| 1 (18–19 years old) | −2.2074 *** | −0.9356 *** | −2.5064 *** | −0.8843 *** |

| 2 (20–21 years old) | −2.9160 *** | −2.6856 *** | 0.8116 | −1.6531 *** |

| 3 (22–23 years old) | 1.1142 ** | 1.3612 *** | 2.3670 *** | −1.1844 * |

| 4 (24–25 years old) | 1.6378 ** | 1.3466 ** | 1.6385 ** | −1.2708 * |

| 5 (26–27 years old) | 0.1495 ** | 1.3197 ** | 1.9039 *** | 0.2432 *** |

| 6 (28–29 years old) | 0.1621 ** | 0.4590 ** | 0.7205 ** | −0.8725 * |

| 7 (30–31 years old) | 0.0525 ** | −0.4155 | 1.2504 ** | 0.6061 |

| 8 (32–33 years old) | 0.5943 ** | 1.4262 ** | 0.5546 ** | −0.4013 |

| 9 (34–35 years old) | −0.9836 ** | 0.7038 ** | 0.6850 ** | 0.1660 ** |

| 10 (36–37 years old) | 2.2075 *** | 0.3430 * | 0.2500 * | −1.2145 ** |

| 11 (38–39 years old) | −0.2697 ** | 0.6380 * | 0.8563 * | −1.0459 ** |

| 12 (40–41 years old) | 0.4319 * | −1.1033 ** | 2.4415 *** | −1.4553 ** |

| 13 (42–43 years old) | −2.568 *** | 0.7369 ** | 1.4557 ** | −1.2063 ** |

| Cohort | Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| 1 (18–19 years old) | −1.1934 *** | −1.1732 *** | −0.9322 *** | −0.8812 *** |

| 2 (20–21 years old) | −0.6226 *** | −0.6419 *** | −0.8348 *** | −0.7981 *** |

| 3 (22–23 years old) | −0.8709 *** | −0.6924 *** | −0.6611 *** | −0.5826 *** |

| 4 (24–25 years old) | −0.7134 *** | −0.5722 *** | −0.5019 *** | −0.4552 *** |

| 5 (26–27 years old) | −0.3587 *** | −0.3797 *** | −0.3618 *** | −0.4884 *** |

| 6 (28–29 years old) | −0.4623 *** | −0.2481 *** | −0.2823 *** | −0.2636 *** |

| 7 (30–31 years old) | −0.4022 *** | −0.2876 *** | −0.1343 *** | −0.2826 *** |

| 8 (32–33 years old) | −0.2981 *** | 0.0466 | −0.2199 *** | 0.0220 |

| 9 (34–35 years old) | −0.6255 | 0.0990 | 0.0435 | −0.1227 |

| 10 (36–37 years old) | −0.1043 | 0.0226 | −0.1186 | 0.2150 |

| 11 (38–39 years old) | 0.0057 | 0.2113 | −0.1085 | 0.1683 |

| 12 (40–41 years old) | −0.3164 | −0.0064 | −0.2078 ** | −0.1660 *** |

| 13 (42–43 years old) | 0.1581 | 0.0271 | −0.0113 | −0.0834 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mora, J.J.; Herrera Duque, D.Y.; Sayago, J.T.; Cendales, A. Maternity Leave Reform and Women’s Labor Outcomes in Colombia: A Synthetic Control Analysis. Economies 2025, 13, 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100299

Mora JJ, Herrera Duque DY, Sayago JT, Cendales A. Maternity Leave Reform and Women’s Labor Outcomes in Colombia: A Synthetic Control Analysis. Economies. 2025; 13(10):299. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100299

Chicago/Turabian StyleMora, Jhon James, Diana Yaneth Herrera Duque, Juan Tomas Sayago, and Andres Cendales. 2025. "Maternity Leave Reform and Women’s Labor Outcomes in Colombia: A Synthetic Control Analysis" Economies 13, no. 10: 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100299

APA StyleMora, J. J., Herrera Duque, D. Y., Sayago, J. T., & Cendales, A. (2025). Maternity Leave Reform and Women’s Labor Outcomes in Colombia: A Synthetic Control Analysis. Economies, 13(10), 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100299