Uncorking Rural Potential: Wine Tourism and Local Development in Nemea, Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

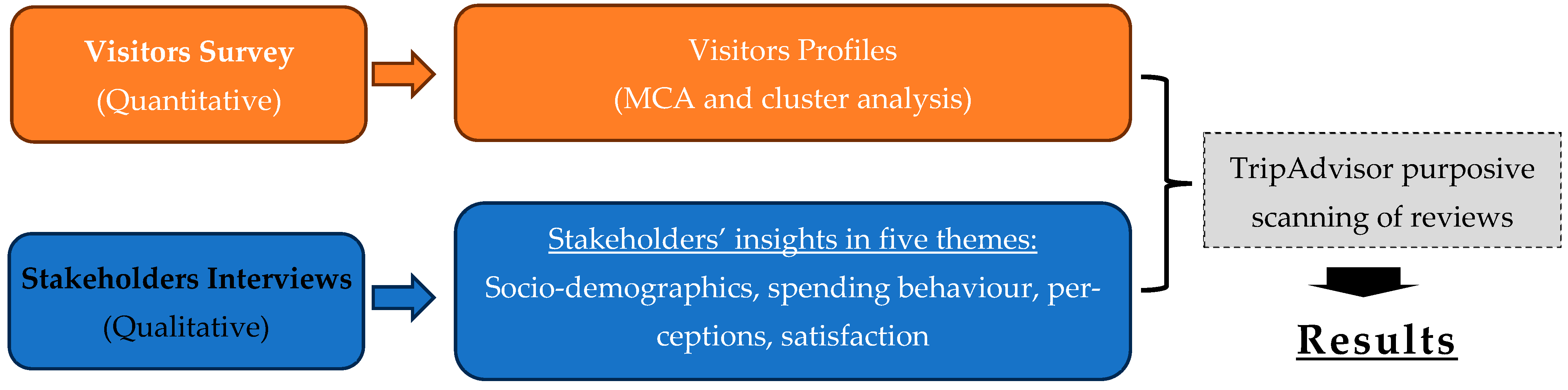

2. Methodology

2.1. Qualitative Analysis

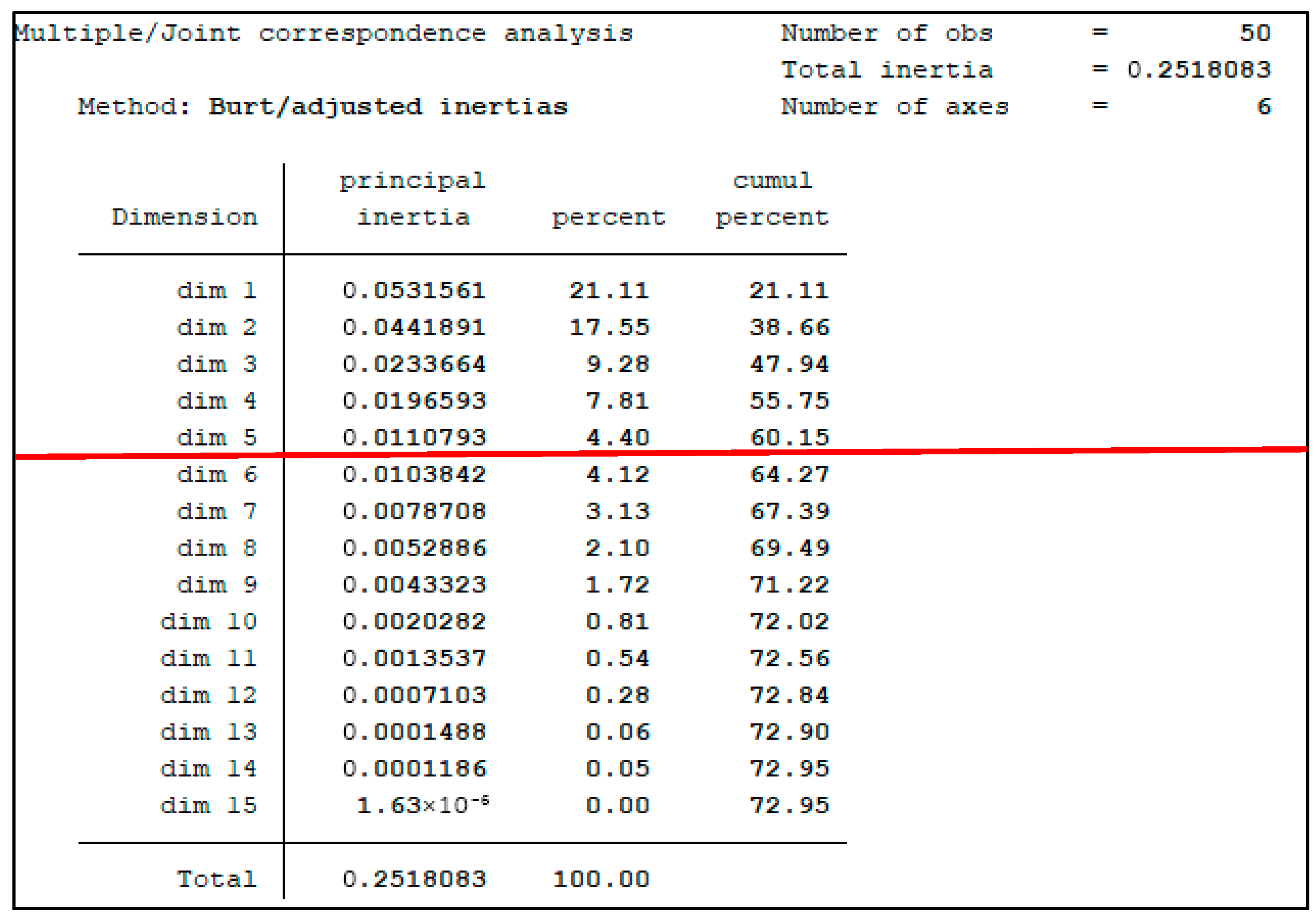

2.2. Quantitative Analysis: Multivariate Framework

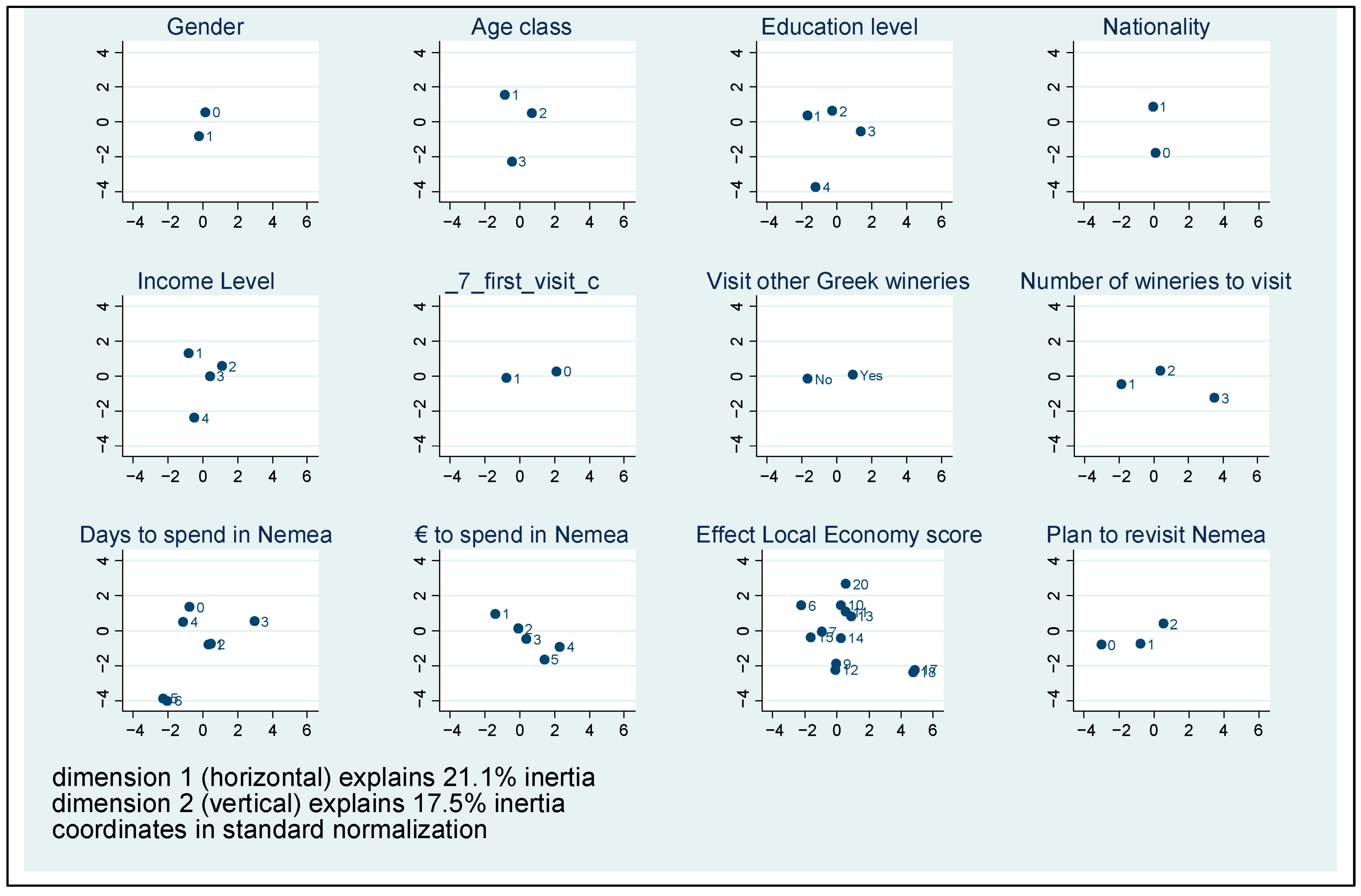

2.2.1. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

- Standardisation of the Indicator Matrix: The indicator matrix is centred and scaled to produce matrix which is defined as:where is an -dimensional vector of ones, are the row and column marginals (proportions), respectively, and is the diagonal matrix of column sums.

- Singular Value Decomposition (SVD): Perform the SVD on matrix :where containing left and right singular vectors, respectively, and is a diagonal matrix of singular values.

- Determination of Dimensions: The principal dimensions are chosen based on the largest singular values. The inertia (analogous to variance in PCA) explained by each dimension is given by:where are the l-th singular value of the matrix Z, represents the contribution of the l-th dimension to the total inertia (i.e., the total variance explained).

- Coordinates Calculation: The coordinates of the observations (rows) and categories (columns) in the reduced space are computed as:

- Interpretation and Visualisation: Observations and categories can then be plotted in the reduced-dimensional space. The proximity of points in the scatterplot reflects associations or similarities among observations and categories.

2.2.2. Cluster Analysis: Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA)/K-Means Clustering

2.3. Triangulation with Online Visitor Reviews (TripAdvisor)

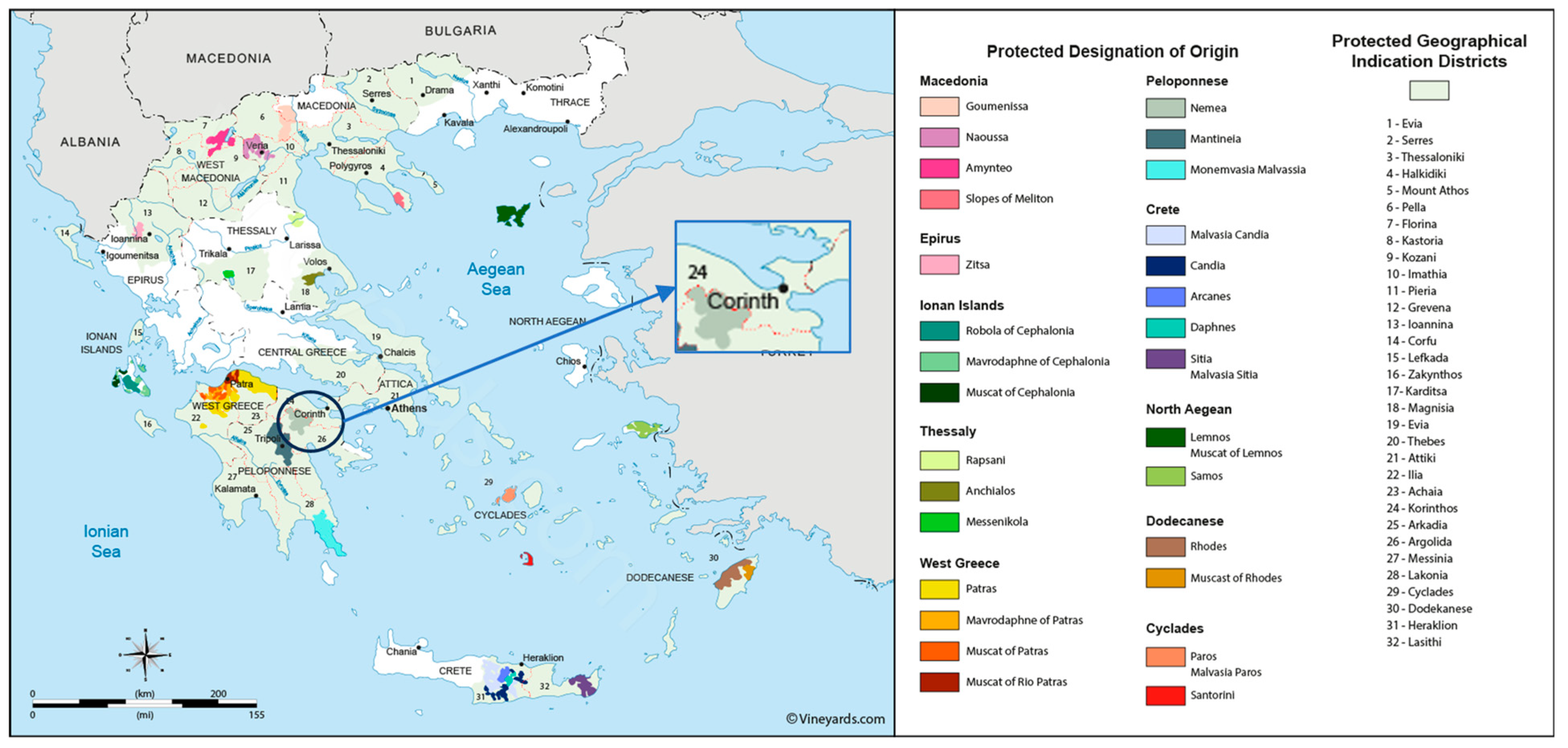

2.4. The Area of Nemea

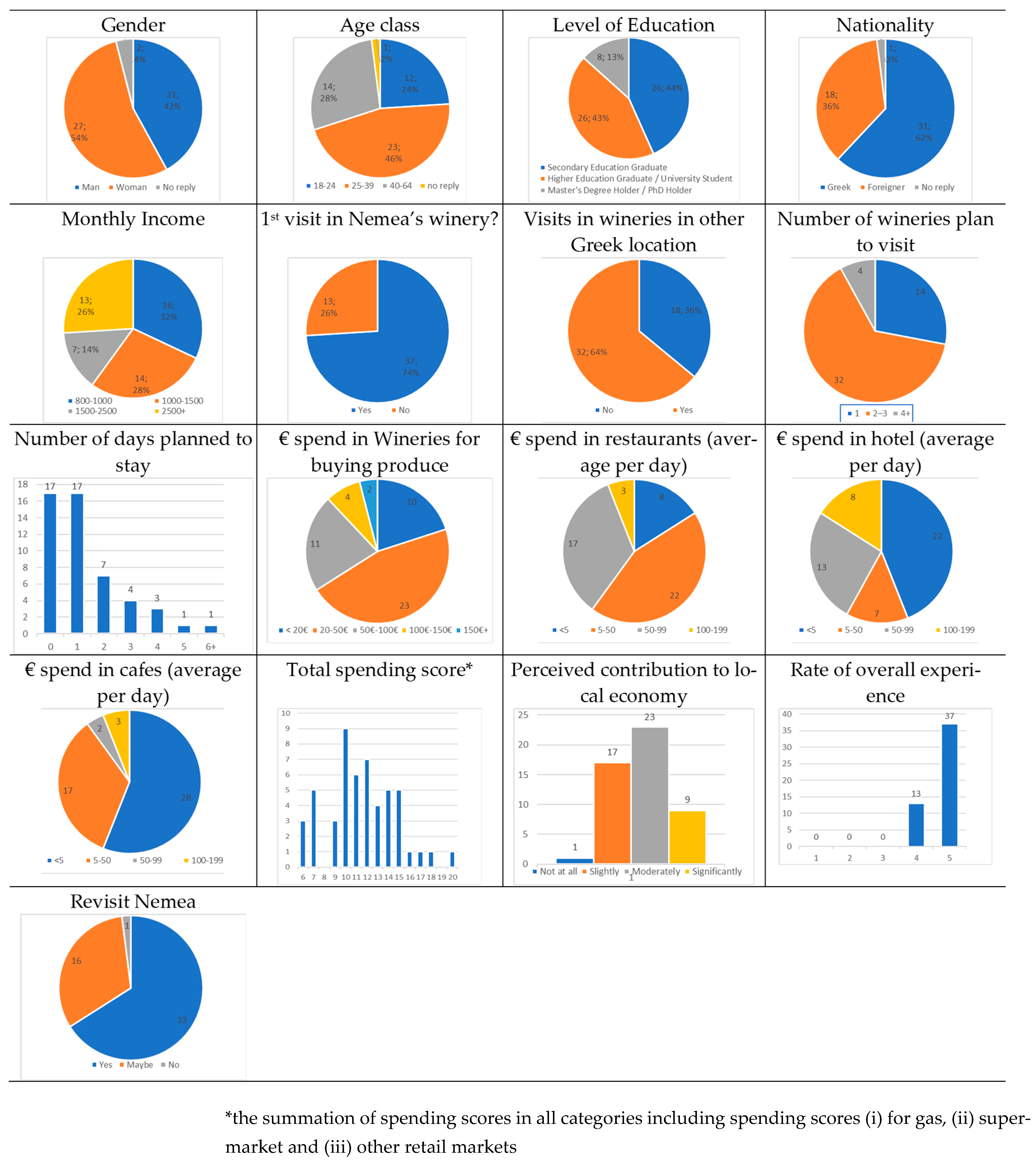

3. Results

3.1. Open Interviews with Local Stakeholders

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

3.2.1. MCA

- Dimension 1: Overall Economic Engagement (21.11% of inertia explained). This is the most impactful dimension in terms of inertia explained. It captures the contrast between economically impactful visitors and more modest or passive tourists. High scorers on this axis are characterised by significant expenditures across multiple categories, particularly wineries, restaurants, and hotels, and longer stays, often exceeding two days. These individuals likely contribute the most to the local economy, not only through direct purchases in wineries but also through their use of local services. At the other end of the spectrum, low scorers tend to be day-trippers or budget-conscious tourists, making minimal purchases and engaging with fewer tourism touchpoints. Their economic footprint is relatively limited, even if their presence is valued from a volume or awareness-building perspective. This dimension is crucial in distinguishing high-value segments from low-intensity visitors, both of which play different but complementary roles in the regional tourism ecosystem.

- Dimension 2: Visitor Type and Familiarity (17.55% of inertia explained). The second dimension, explaining 17.55% of the inertia, reflects visitor experience and relational familiarity with Nemea as a wine tourism destination. Tourists with high scores on this axis tend to be repeat visitors, often visiting multiple wineries and expressing clear intentions to return. Their behaviour indicates both personal investment in the destination and sustained interest in its wine-related offerings. In contrast, low scorers are primarily first-time visitors, many of whom limit their exploration to a single winery and do not plan a return trip in the near future. These visitors may have arrived through broader tourism flows rather than a dedicated interest in wine. This dimension therefore articulates a spectrum from loyal, targeted wine tourists to casual or accidental participants, offering insight into how engagement evolves across different types of visitors.

- Dimension 3: Demographic and Educational Profile (9.28% of inertia explained). This dimension explained a much lower but still significant portion of the inertia (9.28%). It reveals clear demographical patterns in terms of age, income, and education level. High scores are associated with older, highly educated, and affluent individuals, typically those aged 40–64, holding postgraduate degrees, and reporting household incomes above €2500. These visitors may exhibit preferences for more structured, refined, or educational wine tourism experiences. On the lower end of the axis, tourists tend to be younger (18–24), less formally educated, and within lower income brackets. While still important to the tourism base, they may be less likely to engage with premium offerings or complex narratives around terroir and wine production. This axis thus captures the socioeconomic and cultural capital of visitors, which influences both their motivations and the types of experiences they value.

- Dimension 4: Spending Orientation—Gastronomy vs. Winery (7.81% of inertia explained). The fourth dimension differentiates visitors based on how they allocate their spending during their visit. High scorers prioritise gastronomic experiences, spending significantly in restaurants and cafes, often emphasising food and social interaction as key components of their trip. By contrast, low scorers tend to focus their spending on direct winery purchases, suggesting a more wine-driven orientation. These may be individuals who are interested in building their personal wine collection or learning about wine as a commodity, rather than as part of a wider cultural experience. This dimension offers useful insight into visitor priorities, highlighting opportunities for targeted promotion, e.g., food pairing events for high scorers, or cellar-door incentives for low scorers.

- Dimension 5: Tour Structure—Overnight vs. Local (4.40% of inertia explained). This dimension contrasts the structure of a visitor’s trip, particularly whether they are overnight guests or local/same-day visitors. High scorers report hotel spending and longer stay, reflecting a more immersive travel model, often with time allocated to additional cultural or leisure activities. Low scorers, on the other hand, are typically day-trippers or residents of nearby areas, who may participate in winery tours without engaging with the broader tourism infrastructure. Their presence is valuable for volume, local brand awareness, and word-of-mouth, even if their per-visit impact is limited. This dimension is essential for tourism planning, as it relates directly to infrastructure usage, accommodation demand, and strategic investment needs.

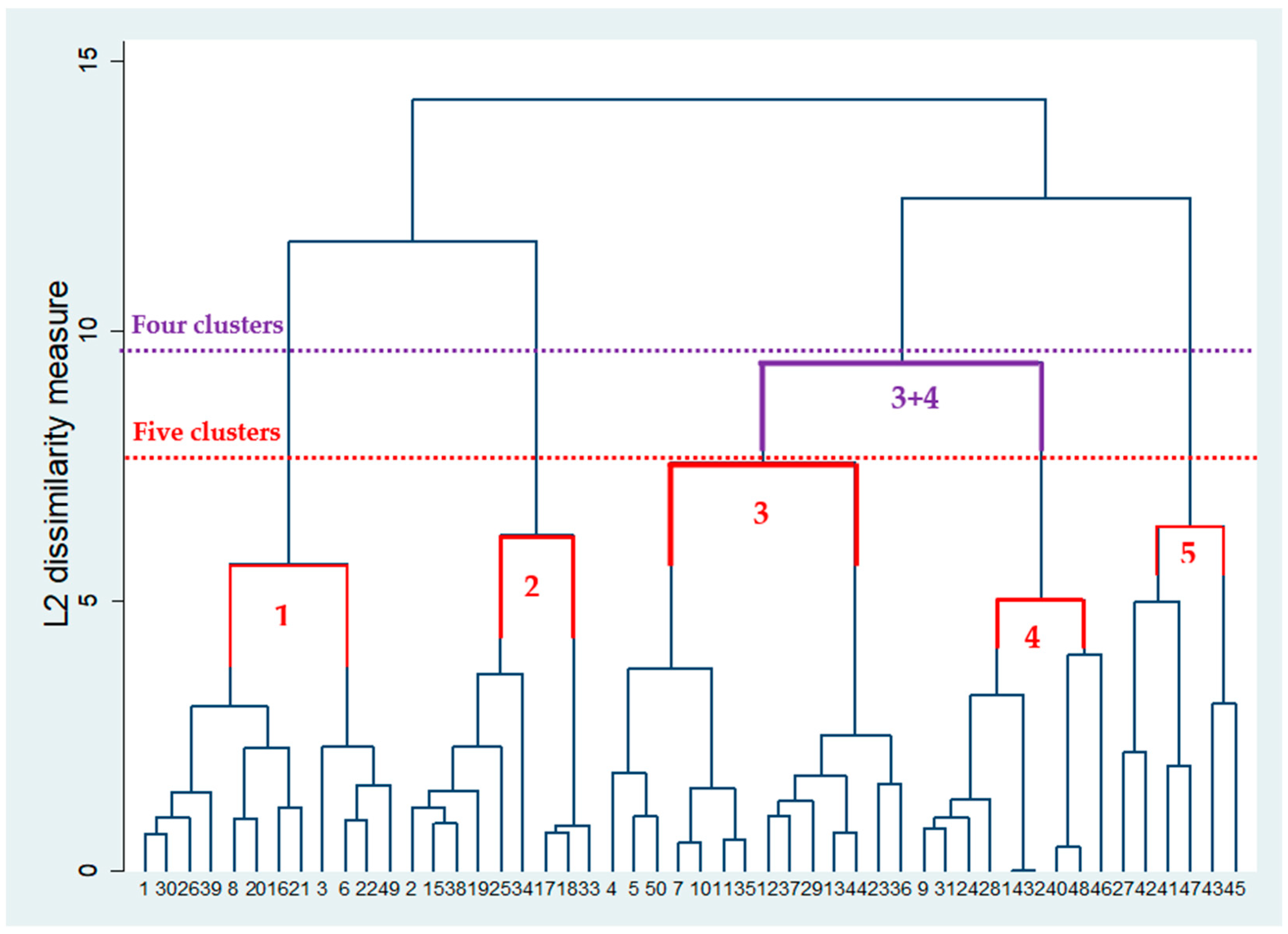

3.2.2. HCA and K-Means

3.3. Triangulation with Online Visitor Reviews (TripAdvisor)

4. Discussion

- Clusters 3 and 5 (high-spend, low-loyalty): premium, export-friendly programmes (private tastings, cellar allocations, limited releases), and curated cultural add-ons to deepen attachment beyond the cellar door (Croce & Perri, 2017; UNWTO, 2016; López-Guzmán et al., 2014).

- Cluster 2 (repeat mid-spenders): loyalty schemes and route-based passes that bundle accommodation, tastings, and gastronomy to drive off-season demand (Dolnicar, 2020; Vazquez Vicente et al., 2021; ACEVIN, 2024).

- Cluster 4 (younger, experience-oriented): affordable experiential products (food-wine pairings, workshops, short trails) that enhance learning and local engagement (UNWTO, 2016; Montella, 2017; Martínez-Falcó et al., 2024).

- Cluster 1 (local day-trippers): event-led programming and urban-amenity upgrades to sustain frequent short visits and strengthen place branding (OECD, 2014; Baggio, 2008; Alebaki et al., 2020).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Overall | Dimension_1 | Dimension_2 | Dimension_3 | Dimension_4 | Dimension_5 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mass | Quality | % inert | coord | Sq. corr | contrib | coord | Sq. corr | contrib | coord | sqcorr | contrib | coord | Sq. corr | contrib | coord | Sq. corr | contrib | |

| gender | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 0.05 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.16 | 0.04 |

| Yes | 0.04 | 0.63 | 0.01 | −0.21 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.80 | 0.27 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.36 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −1.22 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| age class | ||||||||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 0.02 | 0.73 | 0.03 | −0.86 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 1.58 | 0.33 | 0.05 | −0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.16 | 0.28 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 25–39 | 0.04 | 0.66 | 0.02 | 0.70 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.01 | −0.71 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.86 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 40–64 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.04 | −0.46 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −2.25 | 0.59 | 0.12 | 1.39 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| education | ||||||||||||||||||

| Primary | 0.01 | 0.70 | 0.02 | −1.70 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 2.81 | 0.30 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Secondary | 0.04 | 0.71 | 0.01 | −0.26 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.22 | 0.02 | −0.76 | 0.16 | 0.03 | −1.05 | 0.26 | 0.05 | −0.26 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Tertiary | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 1.37 | 0.44 | 0.05 | −0.51 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1.48 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| +MSc | 0.01 | 0.64 | 0.03 | −1.21 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −3.71 | 0.40 | 0.07 | −2.91 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 1.19 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.78 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| nationality | ||||||||||||||||||

| Foreigner | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.74 | 0.70 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.39 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Greek | 0.06 | 0.77 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.04 | −0.14 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Income level | ||||||||||||||||||

| 800–999 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.02 | −0.81 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 1.33 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −1.45 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| 1000–1499 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 1.08 | 0.36 | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 1.04 | 0.12 | 0.03 | −0.71 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| 1500–2499 | 0.01 | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.14 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.15 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| 2500 | 0.02 | 0.74 | 0.03 | −0.50 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −2.37 | 0.64 | 0.12 | −0.79 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| First visit in Nemea? | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.03 | 2.11 | 0.77 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.83 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 0.06 | 0.85 | 0.01 | −0.74 | 0.77 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.20 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Visits to other wineries throughout Greece | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.03 | −1.66 | 0.62 | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.41 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Yes | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.62 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.30 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.57 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Number of Wineries visited/planning to visit in Nemea during stay? | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0.02 | 0.76 | 0.04 | −1.89 | 0.49 | 0.08 | −0.43 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.79 | 0.19 | 0.07 | −0.41 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.80 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 2–3 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.08 | 0.01 | −1.05 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| >3 | 0.01 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 3.52 | 0.55 | 0.08 | −1.24 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 2.17 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Days in Nemea | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.03 | −0.77 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 1.34 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 0.07 | 0.02 | −1.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| 1 | 0.03 | 0.68 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.79 | 0.21 | 0.02 | −1.36 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.33 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.01 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.75 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −1.27 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1.41 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 3 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 2.95 | 0.45 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −1.90 | 0.07 | 0.02 | −0.87 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 4 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 0.02 | −1.12 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −2.54 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 4.66 | 0.23 | 0.11 |

| 5 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.02 | −2.24 | 0.08 | 0.01 | −3.86 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −4.02 | 0.10 | 0.03 | −3.95 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| 6 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.02 | −2.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −4.00 | 0.21 | 0.03 | −3.32 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.50 | 0.14 | 0.07 |

| € spend in wineries | ||||||||||||||||||

| <5 | 0.02 | 0.76 | 0.03 | −1.40 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.96 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 2.04 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.96 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 5–49 | 0.04 | 0.72 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −1.47 | 0.50 | 0.08 | 0.88 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| 50–99 | 0.02 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.47 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.52 | 0.44 | 0.12 | −1.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| 100–149 | 0.01 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 2.28 | 0.29 | 0.04 | −0.90 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.74 | 0.19 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.26 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| 150 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 1.40 | 0.10 | 0.01 | −1.64 | 0.12 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.86 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −3.24 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

| Total score for € spending in Nemea for HORECA and other retail services | ||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | 0.01 | 0.66 | 0.02 | −2.24 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 1.45 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 1.84 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.95 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 7 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 0.01 | −0.94 | 0.14 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.60 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −1.72 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| 9 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.89 | 0.14 | 0.02 | −0.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.17 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −3.39 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| 10 | 0.02 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 2.26 | 0.29 | 0.08 | −0.67 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 11 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.55 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 1.08 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.87 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.11 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 12 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −2.23 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 13 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.84 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −2.04 | 0.15 | 0.03 | −1.74 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 14 | 0.01 | 0.53 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.40 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −2.23 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 1.91 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.71 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| 15 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.02 | −1.63 | 0.26 | 0.02 | −0.37 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −1.38 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −1.80 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 2.06 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| 17 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 0.03 | 4.87 | 0.34 | 0.04 | −2.22 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 4.11 | 0.11 | 0.03 | −2.28 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −2.16 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 18 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 4.77 | 0.31 | 0.04 | −2.36 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 5.52 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.47 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| 20 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.02 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.67 | 0.11 | 0.01 | −0.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −6.17 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 4.99 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| Revisit plan | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.03 | −3.02 | 0.26 | 0.03 | −0.80 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 4.97 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 1.59 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.71 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Maybe | 0.03 | 0.54 | 0.02 | −0.78 | 0.18 | 0.02 | −0.76 | 0.14 | 0.01 | −0.46 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.62 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −1.52 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Yes | 0.06 | 0.64 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

Appendix B

Semi-Structured Interview Guide: Wine Tourism and Local Development in Nemea

- Please describe your role and main responsibilities.

- How long have you been involved in the Nemea wine/visitor economy?

- What does a typical week/month look like in terms of visitor interaction?

- What are Nemea’s main strengths as a wine tourism destination?

- What are the main constraints that limit performance or visitor satisfaction?

- How, if at all, have these changed in the past 2–3 years?

- From your perspective, how prepared are wineries to host visitors (spaces, staffing, languages, booking, pricing)?

- Who are the main types of visitors you see (domestic/international, first-time/repeat, age/income ranges, group vs. independent)?

- How do they typically spend their time and money (wineries, restaurants, cafés, hotels, retail, culture)?

- What drives satisfaction or dissatisfaction?

- In what ways does wine tourism support other local sectors (restaurants, cafés, hotels, retail, transport, guides)?

- Are there existing or potential synergies with archaeological and cultural heritage in the area?

- What bundleable experiences would work well here?

- How adequate are signage, roads, parking, public amenities, and digital wayfinding for independent travellers?

- What practical improvements would make the biggest difference?

- How effectively is Nemea’s PDO/Agiorgitiko identity communicated to visitors?

- What marketing channels or partnerships work best? What is missing?

- Where are the main skills gaps (hospitality, languages, storytelling, digital booking/CRM)?

- What role can the vocational training institute and other bodies play?

- How well do producers and local actors collaborate?

- Thinking of different visitor types (e.g., high-spend short-stay; repeat mid-spenders; younger experience-seekers; local day-trippers; international premium), what targeted actions would you prioritize for each?

- If you could implement three actions in the next 12 months, what would they be?

- Is there anything important I didn’t ask that you would like to add?

- May I contact you if I need to clarify a point?

Appendix C. Coding Matrix for TripAdvisor Reviews

| Category | Example Review Excerpt | Theme/Interpretation |

| Service quality | “The tasting was very well organised and the host was knowledgeable.” | Positive service quality, knowledgeable staff |

| Service quality | “The tasting felt rushed during a busy period and some questions went unanswered.” | Service inconsistency, training gaps |

| Infrastructure and accessibility | “Easy to find, with parking right next to the cellar door.” | Good accessibility |

| Infrastructure and accessibility | “Signage between wineries could be clearer and we relied on GPS to navigate.” | Wayfinding and navigation issues |

| Accommodation and gastronomy | “The food and wine pairing made the visit special.” | Gastronomy as added value |

| Accommodation and gastronomy | “Lodging options in town felt limited, so we stayed outside Nemea.” | Thin accommodation capacity near the destination |

| Authenticity and atmosphere | “Vineyard views and traditional stone cellars made the visit feel authentic.” | Authenticity, place identity linked to Agiorgitiko and the PDO |

| Authenticity and atmosphere | “More storytelling about local history would have enriched the experience.” | Opportunity to strengthen cultural integration |

| Overall satisfaction and loyalty | “We would definitely come back and recommend it to friends.” | High satisfaction, revisit intention |

| Overall satisfaction and loyalty | “Good experience, but probably a one-time visit for us.” | Satisfied but low loyalty |

References

- Abdi, H., & Valentin, D. (2007). Multiple correspondence analysis. Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics, 2(4), 651–657. [Google Scholar]

- Alebaki, M., & Ioannides, D. (2017). Threats and obstacles to resilience: Insights from Greece’s wine tourism. In Tourism, resilience and sustainability (pp. 132–148). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Alebaki, M., Liontakis, A., & Koutsouris, A. (2020, September 17–18). Benchmark analysis of wine tourism destinations: Integrating a resilience system perspective into the comparative framework. 2nd International Research Workshop in Wine Tourism “Wine Tourism: Challenges, Innovation and Futures” (pp. 17–18), Santorini, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiadis, F., & Alebaki, M. (2021). Mapping the Greek wine supply chain: A proposed research framework. Foods, 10(11), 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asociación Española de Ciudades del Vino (ACEVIN). (2024). Wine tourism on Spain’s wine routes generates an economic impact of more than 100 million euros. Ruta del Vino Ribera del Duero. Available online: https://rutadelvinoriberadelduero.es/en/wine-tourism-on-spains-wine-routes-generates-an-economic-impact-of-more-than-100-million-euros/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Baggio, R. (2008). Symptoms of complexity in a tourism system. Tourism Analysis, 13(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E. T., Canziani, B., Hsieh, Y. C. J., Debbage, K., & Sonmez, S. (2016). Wine tourism: Motivating visitors through core and supplementary services. Tourism Management, 52, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliński, T., & Harabasz, J. (1974). A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods, 3(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, R., & Brito, C. (2016). Wine tourism and regional development. In M. Peris-Ortiz, M. Del Río Rama, & C. Rueda-Armengot (Eds.), Wine and tourism. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Croce, E., & Perri, G. (2017). Food and wine tourism: Integrating food, travel and territory (2nd ed.). CABI. [Google Scholar]

- Decrop, A. (1999). Triangulation in qualitative tourism research. Tourism Management, 20(1), 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. (2020). Market segmentation analysis in tourism: A perspective paper. Tourism Review, 75(1), 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, R. O., Hart, P. E., & Stork, D. G. (2001). Pattern classification (2nd ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, S., & Incerti, F. (1997, June 19–21). The wine routes as an instrument for the valorisation of typical products and rural areas. 52nd European Association of Agricultural Economists Seminar (pp. 213–224), Parma, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D., & Carlsen, J. (2005). Family business in tourism: State of the art. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1), 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, R., & Clarke, M. (2019). Economic contribution of the wine sector to Western Australia. AgEconPlus Report for the Wine Industry Association of Western Australia. Available online: https://winewa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/AgEconPlus-Gillespie-Economic-Contribution-Wine-Report-2019.-1-1.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Greenacre, M. (2017). Correspondence analysis in practice (2nd ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Guédé, R., & Koffi, A. T. (2019). Artisanal mining, employment and empowerment in the north and east of Côte d’Ivoire. Theoretical Economics Letters, 9(08), 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M., Sharples, L., Cambourne, B., & Macionis, N. (2000). Wine tourism around the world: Development, management and markets. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Hjellbrekke, J. (2018). Multiple correspondence analysis for the social sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Husson, F., Le, S., & Pagès, J. (2017). Exploratory multivariate analysis by example using R (2nd ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Kazou, M., Pagiati, L., Dotsika, E., Proxenia, N., Kotseridis, Y., & Tsakalidou, E. (2023). The microbial terroir of the Nemea zone Agiorgitiko cv.: A first metataxonomic approach. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research, 2023(1), 8791362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R. V., & Gretzel, U. (2024). Netnography evolved: New contexts, scope, procedures and sensibilities. Annals of Tourism Research, 104, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T., Rodríguez-García, J., Sánchez-Cañizares, S., & José Luján-García, M. (2011). The development of wine tourism in Spain. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 23(4), 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T., Vieira-Rodríguez, A., & Rodríguez-García, J. (2014). Profile and motivations of European tourists on the Sherry wine route of Spain. Tourism Management Perspectives, 11, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. (1967). Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability (Vol. 1, pp. 281–297). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Falcó, J., Martínez-Falcó, J., Marco-Lajara, B., & Sánchez-García, E. (2024). Wine tourism as a catalyst for green performance: The mediating role of green knowledge sharing. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliordos, D. E., Goulioti, E., Lola, D., Kanapitsas, A., Kontoudakis, N., & Kotseridis, Y. (2024). Chemical and sensory differentiation of Nemea PDO sub-zones wines: Two vintages experiment. Ciência e Técnica Vitivinícola, 39(2), 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán-Tudela, L. A., Marco-Lajara, B., Martínez-Falcó, J., & Sánchez-García, E. (2024). Economic structure and geographic scope of Spanish wine routes. In Wine tourism and sustainability: The economic, social and environmental contribution of the wine industry (pp. 33–48). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Mkono, M., & Tribe, J. (2017). Beyond reviewing: Uncovering the multiple roles of tourism social media users. Journal of Travel Research, 56(3), 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montella, M. M. (2017). Wine tourism and sustainability: A review. Sustainability, 9(1), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F., & Legendre, P. (2011). Ward’s hierarchical clustering method: Clustering criterion and agglomerative algorithm. arXiv, arXiv:1111.6285. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2014). Tourism and the creative economy, OECD studies on tourism. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliara, F., Aria, M., Brancati, G., Moradpour, A., & Morrison, A. M. (2025). A mixed-method study for the identification of the factors affecting the performance of a tourist destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 37, 101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, G., & Alebaki, M. (2022). Capturing core experiential aspects in winery visitors’ TripAdvisor reviews: Netnographic insights from Santorini and Crete. In Routledge handbook of wine tourism (pp. 533–543). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R. (2020). Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(11), 1932–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H., & Kaur, K. (2013). New method for finding initial cluster centroids in K-means algorithm. International Journal of Computer Application, 74(6), 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. (2013). Stata: Release 13. Statistical software. StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Sulewski, P., Kłoczko-Gajewska, A., & Sroka, W. (2018). Relations between agri-environmental, economic and social dimensions of farms’ sustainability. Sustainability, 10(12), 4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, T. V., & Kirova, V. (2018). Wine tourism experience: A netnography study. Journal of Business Research, 83, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczynski, A., Rundle-Thiele, S. R., & Beaumont, N. (2009). Segmentation: A tourism stakeholder view. Tourism Management, 30(2), 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzimitra-Kalogianni, I., Papadaki-Klavdianou, A., Alexaki, A., & Tsakiridou, E. (1999). Wine routes in Northern Greece: Consumer perceptions. British Food Journal, 101(11), 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez Vicente, G., Martín Barroso, V., & Blanco Jimenez, F. J. (2021). Sustainable tourism, economic growth and employment—The case of the wine routes of Spain. Sustainability, 13(13), 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, K. (2019). The development of wine tourism in atypical wine regions: The challenge of multistakeholder cooperation? International Studies: Interdisciplinary Political and Cultural Journal, 24(2), 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2016). Georgia declaration on wine tourism: Fostering sustainable tourism development through the promotion of cultural heritage. UNWTO. Available online: https://webunwto.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/imported_images/46325/georgia_declaration.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

| Categories | Variables |

|---|---|

| Demographics | Gender (1: Man; 0: Woman) |

| Age class (1: 18–24; 2: 25–39; 3: 40–64; 4: >64) | |

| Education (1: Primary & secondary; 2: University; 3: Master) | |

| Nationality (1: Greek; 0: foreigner) | |

| Income class (1: <1000, 2: 1000–1500; 3: 1500–2500; 4: >2500) | |

| Tourism behaviour | First Visit in Nemea (1: Yes, 0: No) |

| Number of wineries visited (1: one, 2: two to three; 3: >three) | |

| Days spent in Nemea | |

| Spending patterns: | Spending money for buying in wineries (1: <5 €, 2: 5–49 €; 3: 50–99 €; 4: 100–149 €; 5: 150+ €) |

| Spending money for restaurants (1: <5 €, 2: 5–49 €; 3: 50–99 €; 4: 100–149 €; 5: 150+ €) | |

| Spending money for hotels (1: <5 €, 2: 5–49 €; 3: 50–99 €; 4: 100–149 €; 5: 150+ €) | |

| Spending money for café (1: <5 €, 2: 5–49 €; 3: 50–99 €; 4: 100–149 €; 5: 150+ €) | |

| Total spending score, i.e., the summation of spending scores in all categories including spending scores (i) for gas, (ii) super-market and (iii) other retail markets | |

| Perceptions & preferences: | Perceived contribution to local economy (1: not at all; 2: slight; 3: moderate, 4: High) |

| Rate of experience (from 1 to 5) | |

| Plan to revisit (2: Yes, 1: maybe; 0: No) |

| Dimension | % Inertia | Suggested Name | Key Contrasts | Interpretive Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Dim 1 | 21.11% | Overall Economic Engagement | High-spending, multiday tourists vs. low-spending, short-stay/day-trippers | Distinguishes high-value visitors with greater local economic contribution |

Dim 2 | 17.55% | Visitor Type & Familiarity | Repeat, engaged visitors vs. first-time, low-engagement tourists | Captures depth of visitor experience and future return potential |

Dim 3 | 9.28% | Demographic & Educational Profile | Older, affluent, highly educated vs. younger, less affluent and less educated | Reveals socioeconomic diversity and orientation toward premium experiences |

Dim 4 | 7.81% | Spending Orientation (Gastronomy vs. Winery) | Food- and café-oriented visitors vs. winery-focused spenders | Indicates variation in visitor priorities and preferred types of experiences |

Dim 5 | 4.40% | Tour Structure (Overnight vs. Local) | Hotel-using, multiday tourists vs. day-trippers or local participants | Reflects logistical and infrastructural engagement with the destination |

| Five-Cluster | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-cluster | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total |

| 1 | 12 | 12 | ||||

| 2 | 9 | 9 | ||||

| 3 | 14 | 9 | 23 | |||

| 4 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Total | 12 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 6 | 50 |

| Cluster | Overall Economic Engagement (dim1)  | Visitor Type & Familiarity (dim2)  | Demographic & Educational Profile (dim3)  | Spending Orientation (Gastronomy vs. Winery) (dim4)  | Tour Structure (Overnight vs. Local) (dim5)  | Profile Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −0.77 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.49 | −0.46 | Local Day-Trippers (24%): Repeat visitors; short stays, food-focused |

| 2 | −0.33 | 0.68 | −0.29 | −1.38 | 0.56 | Repeat Mid-Spenders (18%): Repeat visitors focused on wine purchases; moderate income |

| 3 | 0.79 | 0.16 | −0.24 | 0.23 | −0.43 | High-Spend Short-Stay Tourists (28%): High-spending one-timers; low overnight stay |

| 4 | −0.14 | −0.78 | −1.17 | 0.68 | 0.65 | Curious, Educated Explorers (18%): First-timers; younger; food & experience-driven |

| 5 | 0.40 | −1.63 | 1.51 | −0.48 | 0.10 | International Premium Tourists (12%) Affluent, new visitors; detached but valuable |

| Dimensions | Kruskal–Wallis Average Rank Sum per Cluster | Kruskal–Wallis, χ2 Test and Associated Probability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clus_1 | Clus_2 | Clus_3 | Clus_4 | Clus_5 | Chi-Squared (4 d.f.) | Probability | |

| Dimension 1 | 13.50 | 36.25 | 35.92 | 32.67 | 18.25 | 20.85 | 0.000 |

| Dimension 2 | 21.22 | 35.33 | 22.56 | 7.22 | 33.67 | 28.29 | 0.000 |

| Dimension 3 | 38.93 | 26.43 | 23.86 | 27.64 | 19.93 | 33.79 | 0.000 |

| Dimension 4 | 24.44 | 13.11 | 5.00 | 36.33 | 36.22 | 24.21 | 0.000 |

| Dimension 5 | 26.17 | 5.67 | 43.67 | 17.33 | 24.67 | 12.73 | 0.013 |

| Cluster | Type/Naming | Demographic | Visit Duration | Spending Focus | Revisit Intention | Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Local Day-Trippers | Older, well educated, likely higher income | <1 day | Food-oriented, limited overnight stay | High | Low |

| Cluster 2 | Repeat Mid-Spenders | Mid-age, loyal | ~2 days | Winery purchases, product-focused | Moderate | Medium |

| Cluster 3 | High-Spend Short-Stay Tourists | Mixed, affluent | <1 day | Food, wine | Low | High |

| Cluster 4 | Curious, younger explorers | Younger, lower income/education | 1–2 days | Wineries & gastronomy | High | High |

| Cluster 5 | International Premium Tourists | Non-Greek, affluent | 2–3 days | Winery-focused | Low | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liontakis, A.; Bogdani, E. Uncorking Rural Potential: Wine Tourism and Local Development in Nemea, Greece. Economies 2025, 13, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100287

Liontakis A, Bogdani E. Uncorking Rural Potential: Wine Tourism and Local Development in Nemea, Greece. Economies. 2025; 13(10):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100287

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiontakis, Angelos, and Elona Bogdani. 2025. "Uncorking Rural Potential: Wine Tourism and Local Development in Nemea, Greece" Economies 13, no. 10: 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100287

APA StyleLiontakis, A., & Bogdani, E. (2025). Uncorking Rural Potential: Wine Tourism and Local Development in Nemea, Greece. Economies, 13(10), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100287