Facilitating Backward Global Value Chain Participation in South Asia: The Role of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Contributions

3. Empirical Analyses

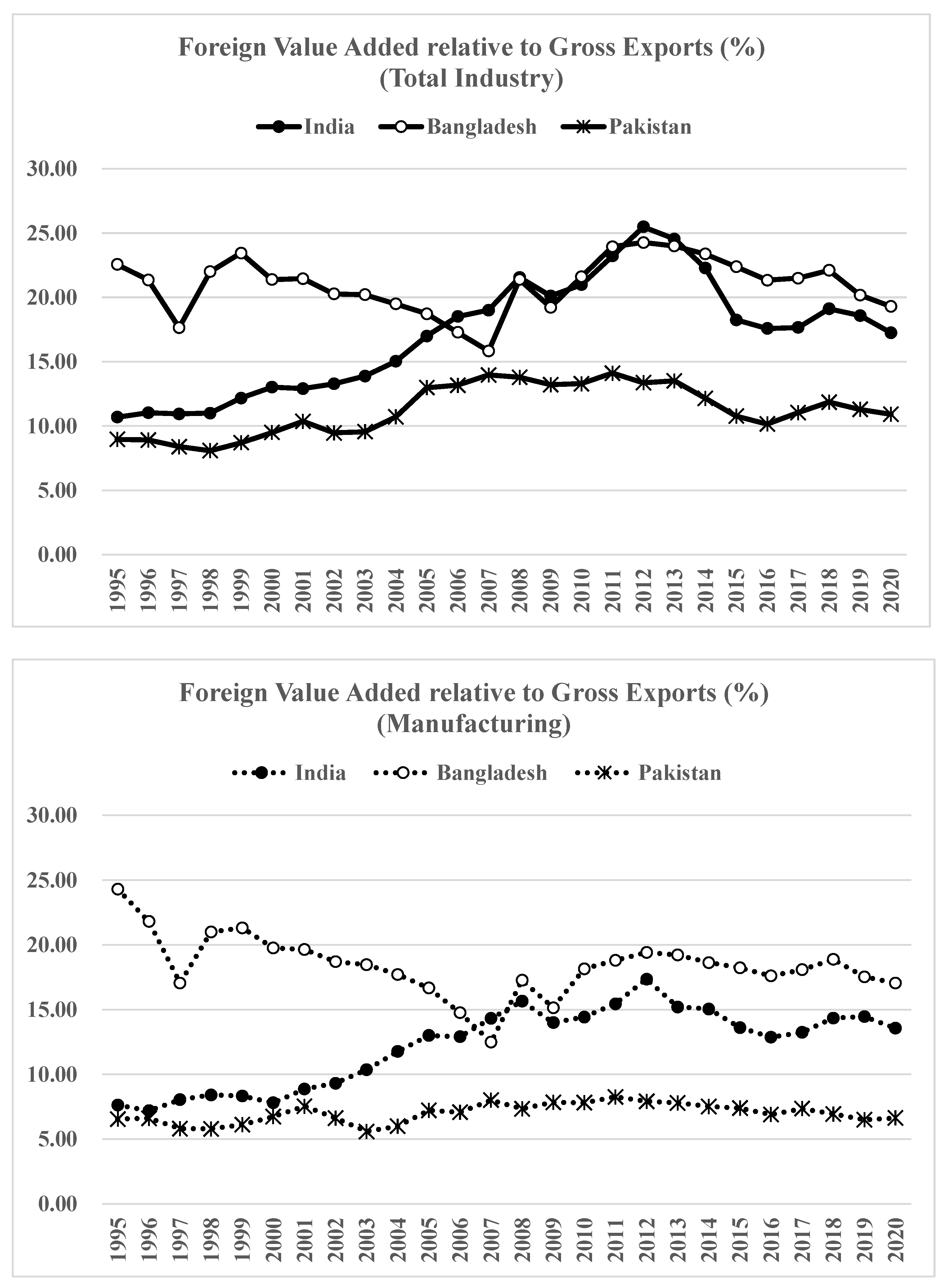

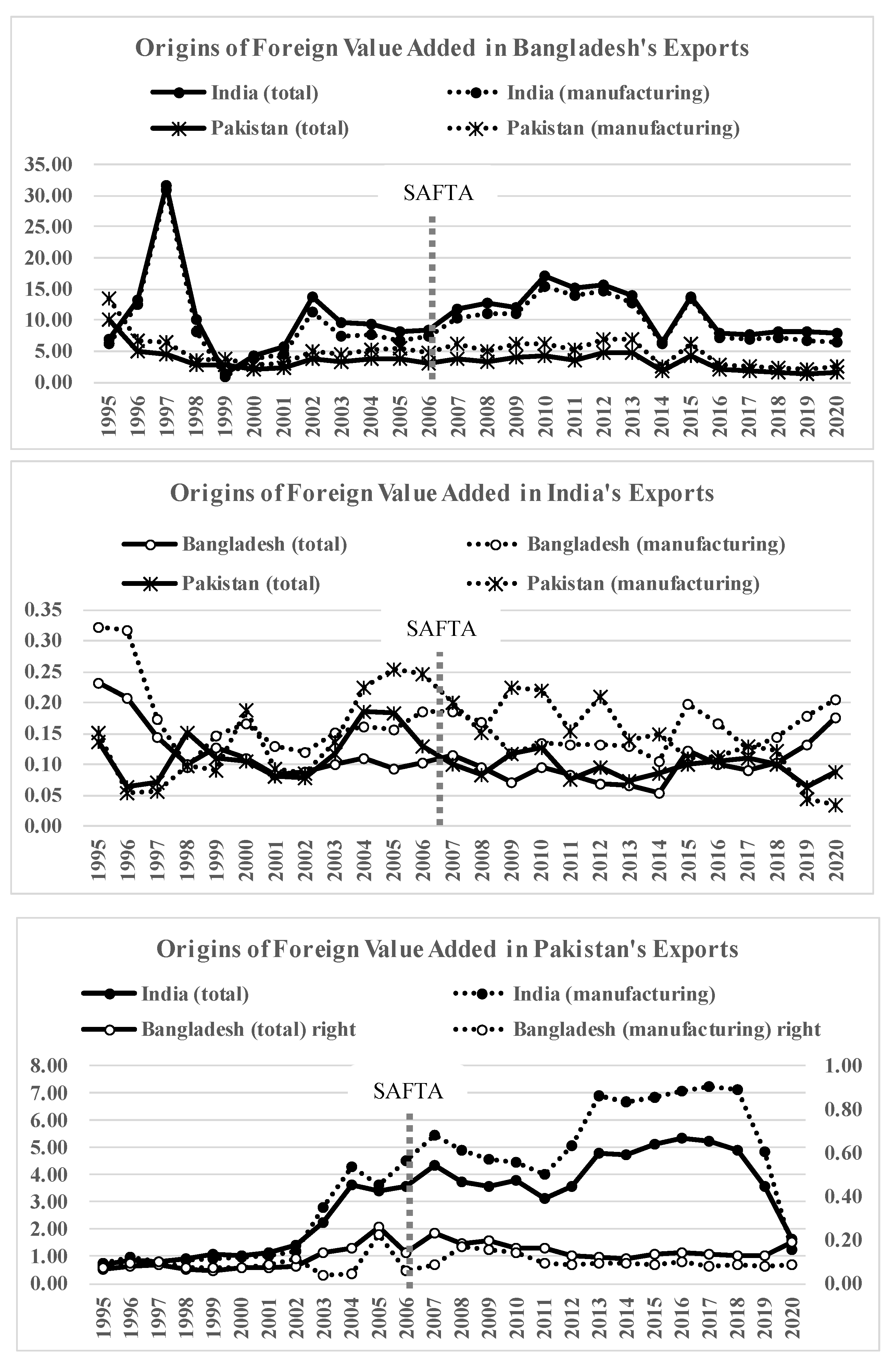

3.1. GVC Trend in South Asian Economies

3.2. Estimation of the Structural Gravity Trade Model

3.2.1. Specification of the Estimation Model

3.2.2. Sample Data

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAFTA | South Asian Free Trade Agreement |

| GVC | Global value chain |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| FTA | Free trade agreement |

| SAARC | South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation |

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| OLS | Ordinary least squares |

| PPML | Poisson pseudo maximum likelihood |

| MFN | Most favored nation |

| NTM | Non-tariff measure |

| 1 | South Asian countries in this study are defined as the members of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, which will be explained in Note 6. |

| 2 | The income class is defined by the World Bank income classification: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (accessed on 1 June 2025). |

| 3 | The method and data of GVC participation ratio is explained in the subsequent section. |

| 4 | The association was established in 1985 by original members Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Afghanistan has joined in 2007 and SAFTA in 2011. |

| 5 | The FTA information is based on the World Trade Organization (WTO): https://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicAllRTAList.aspx (accessed on 1 June 2025). |

| 6 | See the website: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/ (accessed on 1 June 2025). |

| 7 | The trade data here is retrieved from UNCTAD Stat: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/ (accessed on 1 June 2025). |

| 8 | The FTAs sampled in this study are limited due to the TiVA 2023 dataset’s availability constraints. We consider SAFTA and FTAs between India and ASEAN, India and Japan, India and Korea, India and Singapore, Pakistan and China, and Pakistan and Malaysia. |

| 9 | The impacts of non-tariff measures (NTMs) such as technical regulations, health measures, requirements at the borders by customs administration are implicitly incorporated in these bilateral trade costs. The necessity to address the NTMs effects explicitly will be discussed in Section 4 and Section 5. |

| 10 | The origin economies include a host country (domestic value-added) following the recommendation (iii) of Piermartini and Yotov (2016), as stated in Section 3.2.1. |

References

- Alvarez, J. B., Baris, K., Crisostomo, M. C., de Vera, J. P., Gao, Y., Garay, K. A. V., Gonzales, P. B., Jabagat, C. J., Juani, A. S., Lumba, A. B., Mariasingham, M. J., Meng, B., Rahnema, L. C., Reyes, K. S., San Pedro, M. P., & Yang, C. (2021). Recent trends in global value chains. In Asian Development Bank, The Research Institute for Global Value Chains at the University of International Business and Economics, The World Trade Organization, The Institute of Developing Economies–Japan External Trade Organization & The China Development Research Foundation (Eds.), Global value chain development report 2021: Beyond production. Asian Development Bank. Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/global-value-chain-development-report-2021 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. (2007). Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? Journal of International Economics, 71(1), 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I. (2001). Unit root tests for panel data. Journal of International Money and Finance, 20(2), 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, K., & Mayer, T. (2014). Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In G. Gopinath, E. Helpman, & K. S. Rogoff (Eds.), Handbook of international economics (pp. 131–195). Elsevier Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummels, D., Ishii, J., & Yi, K. M. (2001). The nature and growth of vertical specialization in world trade. Journal of International Economics, 54(1), 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115(1), 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A., Bloch, H., & Salim, R. (2014). How effective is the free trade agreement in South Asia? An empirical investigation. International Review of Applied Economics, 28(5), 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. W., & Kierzkowski, H. (2005). International trade and agglomeration: An alternative framework. Journal of Economics, 86(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, F., Takahashi, Y., & Hayakawa, K. (2007). Fragmentation and parts and components trade: Comparison between East Asia and Europe. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 18(1), 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, R., Powers, W., Wang, Z., & Wei, S. J. (2011). Give credit where credit is due: Tracing value added in global production chains. NBER working paper, No. 16426. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1949669 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Koopman, R., Wang, Z., & Wei, S.-J. (2014). Tracing value-added and double counting in gross exports. American Economic Review, 104(2), 459–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A., Lin, C. F., & James Chu, C. S. J. (2002). Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics, 108(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddala, G. S., & Wu, S. A. (1999). A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61(Suppl. S1), 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F., & Jongwanich, J. (2018). Export-enhancing effects of free trade agreements in South Asia. Journal of South Asian Development, 13(1), 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, M. (2015). Impact of free trade agreements on trade in East Asia. In ERIA discussion paper series. [Google Scholar]

- Piermartini, R., & Yotov, Y. V. (2016). Estimating trade policy effects with structural gravity. WTO staff working papers. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2828613 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Rahman, M. M., & Strutt, A. (2023). Trade-restricting impacts of non-tariff measures in Bangladesh. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 28(3), 1117–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F. M., Ram, N., Syed, A. A. G., & Shah, A. S. S. (2015). Impact of trade liberalization and South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) on textile and rice export on Pakistan’s economy. Romanian Statistical Review, 63(8), 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, L. B. (2021). Impact of India-ASEAN free trade agreement: An assessment from the trade creation and trade diversion effects. Foreign Trade Review, 56(4), 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, P., & Sreejesh, S. (2011). The bilateral trade agreements and export performance of South Asian nations with special reference to India Sri Lanka free trade agreement. Romanian Economic Journal, 14(42), 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, H. (2015). Trade creation and diversion effects of ASEAN-plus-one free trade agreements. Economics Bulletin, 35(3), 1856–1866. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, H., & Rubasinghe, D. C. I. (2019). Trade impacts of South Asian free trade agreements in Sri Lanka. South Asia Economic Journal, 20(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, H., & Tsukada, Y. (2022). Premature deindustrialization risk in Asian latecomer developing economies. Asian Economic Papers, 21(2), 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, S., & Okabe, M. (2014). Trade creation and diversion effects of regional trade agreements: A product-level analysis. The World Economy, 37(2), 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, J. (1950). The customs union issue. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe, A., & Yogarajah, C. (2022). Trade policy impact on global value chain participation of the South Asian countries. Journal of Asian Economic Integration, 4(1), 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2016). Making global value chains: Work for development. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2020). World development report—Trading for development in the age of global value chains. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R., Zhao, J., & Zhao, J. (2021). Effects of free trade agreements on global value chain trade—A research perspective of GVC backward linkage. Applied Economics, 53(44), 5122–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population in 2022 (in Million) | GDP per Capita in 2022 (in US$) | Income Class in 2023 | Manufacturing % of GDP in 2022 | GVC Participation in Manufacturing % in 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 34.3 | 422 | low | 10.2 | - |

| Bangladesh | 168.5 | 2731 | lower-middle | 21.8 | 25.2 |

| Bhutan | 0.8 | 3775 | lower-middle | 8.7 | - |

| India | 1417.2 | 2366 | lower-middle | 13.1 | 27.0 |

| Maldives | 0.4 | 15,962 | upper-middle | 2.0 | - |

| Nepal | 30.5 | 1337 | lower-middle | 4.8 | - |

| Pakistan | 227.0 | 1651 | lower-middle | 13.8 | 12.5 |

| Sri Lanka | 22.4 | 3342 | lower-middle | 19.7 | - |

| Average | - | - | - | 11.8 | 21.6 |

| Malaysia | 32.7 | 12,466 | upper-middle | 23.4 | 42.6 |

| Thailand | 70.1 | 7073 | upper-middle | 27.1 | 38.1 |

| Babgladesh | India | Pakistan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign Origins | Value | Share | Value | Share | Value | Share |

| mil. USD | % of Total FVA | mil. USD | % of Total FVA | mil. USD | % of Total FVA | |

| Australia | 58 | 0.7 | 1689 | 2.0 | 35 | 1.1 |

| Canada | 58 | 0.7 | 728 | 0.8 | 23 | 0.7 |

| Japan | 179 | 2.1 | 2360 | 2.8 | 62 | 2.0 |

| Korea | 150 | 1.8 | 1902 | 2.2 | 56 | 1.8 |

| Mexico | 56 | 0.7 | 789 | 0.9 | 9 | 0.3 |

| United States | 414 | 4.9 | 8517 | 9.9 | 206 | 6.5 |

| Bangladesh | - | - | 151 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.2 |

| Brazil | 60 | 0.7 | 804 | 0.9 | 38 | 1.2 |

| China | 2576 | 30.3 | 9978 | 11.6 | 832 | 26.3 |

| India | 673 | 7.9 | - | - | 51 | 1.6 |

| Indonesia | 134 | 1.6 | 2197 | 2.6 | 85 | 2.7 |

| Malaysia | 28 | 0.3 | 1079 | 1.3 | 32 | 1.0 |

| Pakistan | 142 | 1.7 | 75 | 0.1 | - | - |

| Russia | 71 | 0.8 | 1561 | 1.8 | 39 | 1.2 |

| Saudi Arabia | 53 | 0.6 | 7181 | 8.4 | 169 | 5.4 |

| Singapore | 65 | 0.8 | 1631 | 1.9 | 50 | 1.6 |

| South Africa | 28 | 0.3 | 841 | 1.0 | 62 | 2.0 |

| Chinese Taipei | 161 | 1.9 | 719 | 0.8 | 39 | 1.2 |

| Thailand | 279 | 3.3 | 952 | 1.1 | 43 | 1.3 |

| European Union | 1333 | 15.7 | 10,766 | 12.6 | 363 | 11.5 |

| Total | 6516 | 76.7 | 53,920 | 62.9 | 2201 | 69.7 |

| World | 8495 | 85,754 | 3158 |

| Common Unit Root | Individual Unit Root | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levin, Lin, and Chu Test | Fisher-ADF Chi-Square | Fisher-PP Chi-Square | Im, Pesaran, and Shin W-Stat | |

| ln (FVA_T) | −13.150 *** | 193.591 *** | 113.386 | −5.149 *** |

| ln (FVA_M) | −13.407 *** | 200.572 *** | 127.399 | −5.392 *** |

| Total Inductry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation | a_i | a_ii | a_iii | a_iv |

| Methodology | OLS | PPML | ||

| SAFTA | 0.526 *** | 0.496 | 0.134 *** | −0.106 |

| (4.366) | (1.556) | (5.124) | (−1.629) | |

| SAFTA (−1) | 0.130 | 0.147 * | ||

| (0.302) | (1.854) | |||

| SAFTA (−2) | 0.058 | 0.200 *** | ||

| (0.135) | (2.938) | |||

| SAFTA (−3) | −0.177 | −0.101 ** | ||

| (−0.557) | (−2214) | |||

| Other FTAs | ||||

| India & ASEAN | 0.189 | 0.189 | 0.228 *** | 0.228 *** |

| India & Japan | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.084 ** | 0.083 ** |

| India & Korea | 0.931 *** | 0.931 *** | 1.176 *** | 1.176 *** |

| India & Singapore | −0.125 | −0.125 | 0.083 | 0.083 |

| Pakistan & China | 0.349 | 0.349 | 0.195 *** | 0.194 *** |

| Pakistan & Malaysia | 0.836 *** | 0.835 *** | 1.088 *** | 1.087 *** |

| it fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| jt fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| i.j fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R−squared | 0.945 | 0.945 | − | − |

| Manufacturing | ||||

| Estimation | b_i | b_ii | b_iii | b_iv |

| methodology | OLS | PPML | ||

| SAFTA | 0.617 *** | 0.499 | 0.108 *** | −0.150 *** |

| (4.096) | (1.254) | (80.417) | (−43.254) | |

| SAFTA (−1) | 0.170 | 0.149 *** | ||

| (0.314) | (34.800) | |||

| SAFTA (−2) | 0.174 | 0.193 *** | ||

| (0.323) | (52.908) | |||

| SAFTA (−3) | −0.240 | −0.076 *** | ||

| (−0.604) | (−31.787) | |||

| Other FTAs | ||||

| India & ASEAN | 0.471 ** | 0.471 ** | 0.393 *** | 0.393 *** |

| India & Japan | 0.206 | 0.206 | 0.230 *** | 0.229 *** |

| India & Korea | 1.077 *** | 1.077 *** | 1.377 *** | 1.376 *** |

| India & Singapore | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.442 *** | 0.442 *** |

| Pakistan & China | 0.654 ** | 0.654 ** | 0.417 *** | 0.417 *** |

| Pakistan & Malaysia | 0.854 *** | 0.853 *** | 0.564 *** | 0.564 *** |

| it fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| jt fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| i.j fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adjusted R−squared | 0.920 | 0.920 | − | − |

| Estimation | c_i | c_ii |

|---|---|---|

| Industry | Total | Manufacturing |

| Methodology | PPML | PPML |

| exporter/FV origin in SAFTA | ||

| Bangladesh/India | 0.283 *** | 0.081 *** |

| Bangladesh/India (−1) | 0.248 ** | 0.204 *** |

| Bangladesh/India (−2) | 0.262 *** | 0.327 *** |

| Aggregate of Significant effects | 0.793 | 0.612 |

| Bangladesh/Pakistan | 0.074 | 0.076 *** |

| Bangladesh/Pakistan (−1) | 0.122 | 0.102 *** |

| Bangladesh/Pakistan (−2) | 0.074 | −0.001 |

| Aggregate of Significant effects | − | 0.178 |

| India/Bangladesh | −1.628 *** | −1.518 *** |

| India/Bangladesh (−1) | 0.138 | 0.107 *** |

| India/Bangladesh (−2) | −0.088 | −0.196 *** |

| Aggregate of Significant effects | −1.628 | −1.607 |

| India/Pakistan | −0.245 | 0.169 *** |

| India/Pakistan (1) | −0.238 | −0.096 *** |

| India/Pakistan (2) | 0.021 | −0.387 *** |

| Aggregate of Significant effects | − | −0.314 |

| Pakistan/Bangladesh | −2.028 *** | −3.908 *** |

| Pakistan/Bangladesh (−1) | 0.378 | 0.551 *** |

| Pakistan/Bangladesh (−2) | −0.486 | 0.044*** |

| Aggregate of Significant effects | −2.028 | −3.401 |

| Pakistan/India | 1.457 *** | 1.403 *** |

| Pakistan/India (−1) | 0.263 | 0.327 *** |

| Pakistan/India (−2) | −0.197 * | −0.071 *** |

| Aggregate of Significant effects | 1.260 | 1.659 |

| Other FTAs | ||

| India & ASEAN | 0.213 *** | 0.380 *** |

| India & Japan | 0.063 | 0.216 *** |

| India & Korea | 1.142 *** | 1.349 *** |

| India & Singapore | 0.060 | 0.430 *** |

| Pakistan & China | 0.195 *** | 0.417 *** |

| Pakistan & Malaysia | 1.081 *** | 0.557 *** |

| it fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| jt fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| i,j fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Total | Average Tariff Rate for Common Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Items | Tariff Rate | |

| Bangladesh, total, 2015 | ||

| MFN | 4250 | 13.3 |

| SAFTA (India & Pakistan) | 2.8 | |

| Bangladesh, manufacturing, 2015 | ||

| MFN | 3268 | 11.5 |

| SAFTA (India & Pakistan) | 2.4 | |

| India, total, 2008 | ||

| MFN | 3269 | 16.6 |

| SAFTA (Pakistan) | 11.6 | |

| SAFTA for LDCs (Bangladesh) | 3.4 | |

| India, manufacturing, 2008 | ||

| MFN | 2663 | 13.3 |

| SAFTA (Pakistan) | 10.1 | |

| SAFTA for LDCs (Bangladesh) | 3.2 | |

| Pakistan, total, 2008 | ||

| MFN | 1651 | 18.2 |

| SAFTA (India) | 15.6 | |

| SAFTA for LDCs (Bangladesh) | 10.5 | |

| Pakistan, manufacturing, 2008 | ||

| MFN | 1395 | 18.9 |

| SAFTA (India) | 16.1 | |

| SAFTA for LDCs (Bangladesh) | 10.8 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bushra, B.; Taguchi, H. Facilitating Backward Global Value Chain Participation in South Asia: The Role of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement. Economies 2025, 13, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100285

Bushra B, Taguchi H. Facilitating Backward Global Value Chain Participation in South Asia: The Role of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement. Economies. 2025; 13(10):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100285

Chicago/Turabian StyleBushra, Batool, and Hiroyuki Taguchi. 2025. "Facilitating Backward Global Value Chain Participation in South Asia: The Role of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement" Economies 13, no. 10: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100285

APA StyleBushra, B., & Taguchi, H. (2025). Facilitating Backward Global Value Chain Participation in South Asia: The Role of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement. Economies, 13(10), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100285